www.tullynallycastle.com

Open in 2024:

Castle, May 2-31, June 1-29, July 4-20, Aug 1-31, Sept 5-21, Thurs- Sat, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 11am-3pm

Garden, May 2-Sept 29, Thurs-Sundays, and Bank Holidays, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 11am-5pm

Fee: castle/garden adult €16.50, child over 10 years €8.50, OAP/student free, garden, adult €8.50, child €4, family ticket (2 adults + 2 children) €23, adult season ticket €56, family season ticket €70, special needs visitor with support carer €4

2024 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2024 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

We visited Tullynally Castle and Gardens when we were staying near Castlepollard with friends for the August bank holiday weekend in 2020. Unfortunately the house tour is only given during Heritage Week, but we were able to go on the Below Stairs tour, which is really excellent and well worth the price.

In 2021 I prioritised seeing Tullynally during Heritage Week, and we went on the upstairs tour!

According to Irish Historic Houses, by Kevin O’Connor, Tullynally Castle stretches for nearly a quarter of a mile: “a forest of towers and turrets pierced by a multitude of windows,” and is the largest castle still lived in by a family in Ireland [1]. It has nearly an acre of roof! It has been the seat of the Pakenham family since 1655. I love that it has stayed within the same family, and that they still live there. I was sad to hear of Valerie Pakenham’s death recently – she wrote wonderful books of history and on Irish historic houses.

The current incarnation of the Castle is in the romantic Gothic Revival style, and it stands in a large wooded demesne near Lake Derravaragh in County Westmeath.

We stayed for the weekend even closer to Lake Derravaragh, and I swam in it!

The lands of Tullynally, along with land in County Wexford, were granted to Henry Pakenham in 1655 in lieu of pay for his position as Captain of a troop of horse for Oliver Cromwell. [2] [3] His grandfather, Edward (or Edmund) Pakenham, had accompanied Sir Henry Sidney from England to Ireland when Sir Sidney, a cousin of Edward Pakenham, was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland. [4]

A house existed on the site at the time and parts still exist in the current castle. It was originally a semi-fortified Plantation house. When Henry Pakenham moved to Tullynally the house became known as Pakenham Hall. It is only relatively recently that it reverted to its former name, Tullynally, which means “hill of the swans.”

Henry was an MP for Navan in 1667. He settled at Tullynally. He married Mary Lill, the daughter of a Justice of the Peace in County Meath and left the property to his oldest son by this marriage, Thomas (1649-1706) who became a member of Parliament and an eminent lawyer. Henry remarried after his first wife died, this time to Anne Pigot and he had at least two more children with her.

Thomas, who held the office of Prime Sergeant-at-law in 1695, married first Mary Nelmes, daughter of an alderman in London. Thomas married a second time in 1696 after his first wife died, Mary Bellingham, daughter of Daniel, 1st Baronet Bellingham, of Dubber, Co. Dublin. His oldest son, by his first wife, Edward (1683-1721), became an MP for County Westmeath between 1714 and 1721. A younger son, Thomas (d. 1722) lived at Craddenstown, County Westmeath.

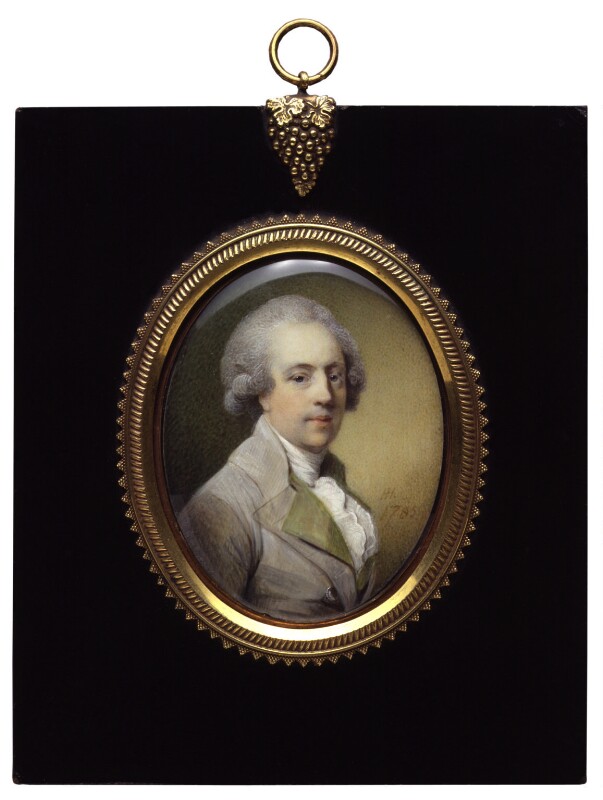

Edward (1683-1721) married Margaret Bradeston and was succeeded by his son, Thomas Pakenham (1713-1766) [see 3]. After her husband died in 1721, Margaret married Reverend Ossory Medlicott. Edward’s younger son George Edward (1717-1768) became a merchant in Hamburg.

Thomas (1713-1766) married Elizabeth Cuffe (1719-1794), the daughter of Michael Cuffe (1694-1744) of Ballinrobe, County Mayo. Her father was heir to Ambrose Aungier (d. 1704), 2nd and last Earl of Longford (1st creation). Michael Cuffe sat as a Member of Parliament for County Mayo and the Borough of Longford. In 1756 the Longford title held by his wife’s ancestors was revived when Thomas was raised to the peerage as Baron Longford. After his death, his wife Elizabeth was created Countess of Longford in her own right, or “suo jure,” in 1785.

Michael Cuffe had another daughter, Catherine Anne Cuffe, by the way, who married a Bagot, Captain John Lloyd Bagot (d. 1798). I haven’t found whether my Baggots are related to these Bagots but it would be nice to have such ancestry! Even nicer because his mother, Mary Herbert, came from Durrow Abbey near Tullamore, a very interesting looking house currently standing empty and unloved.

Thomas’s son, Edward Michael Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford (1743-92) had Pakenham Hall enlarged in 1780 to designs by Graham Myers who in 1789 was appointed architect to Trinity College, Dublin. Myers created a Georgian house. The Buildings of Ireland website tells us that the original five bay house had a third floor added at this time. [5]

The oldest parts still surviving from the improvements carried out around 1780 are some doorcases in the upper rooms and a small study in the northwest corner of the house. We did not see these rooms, but Christine Casey and Alistair Rowan tell us that the study has a dentil cornice and a marble chimneypiece with a keystone of around 1740. [see 2] The oldest part of the castle is at the south end, and still holds the principal rooms.

Edward Michael Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford, married Catherine Rowley, daughter of Hercules Langford Rowley of Summerhill, County Kilkenny, in 1768. He was in the Royal Navy but retired from the military in 1766, when he succeeded as 2nd Baron Longford. He was appointed Privy Counsellor in Ireland in 1777.

Admiral Thomas Pakenham (1757-1836), a younger brother of Edward Michael Pakenham, the 2nd Baron Longford, built another house on the Tullynally estate, Coolure House, around 1775, when he married Louisa Anne Staples, daughter of John Staples (1736-1820), MP for County Tyrone and owner of Lissan House in County Tyrone – which can now be visited, https://www.lissanhouse.com/ . Their son Edward Michael Pakenham (1786-1848) inherited Castletown in County Kildare and he legally changed his name to Edward Michael Conolly. Louisa Anne Staples’s mother was Harriet Conolly, daughter of William Conolly (1712-1754) of Castletown, County Kildare.

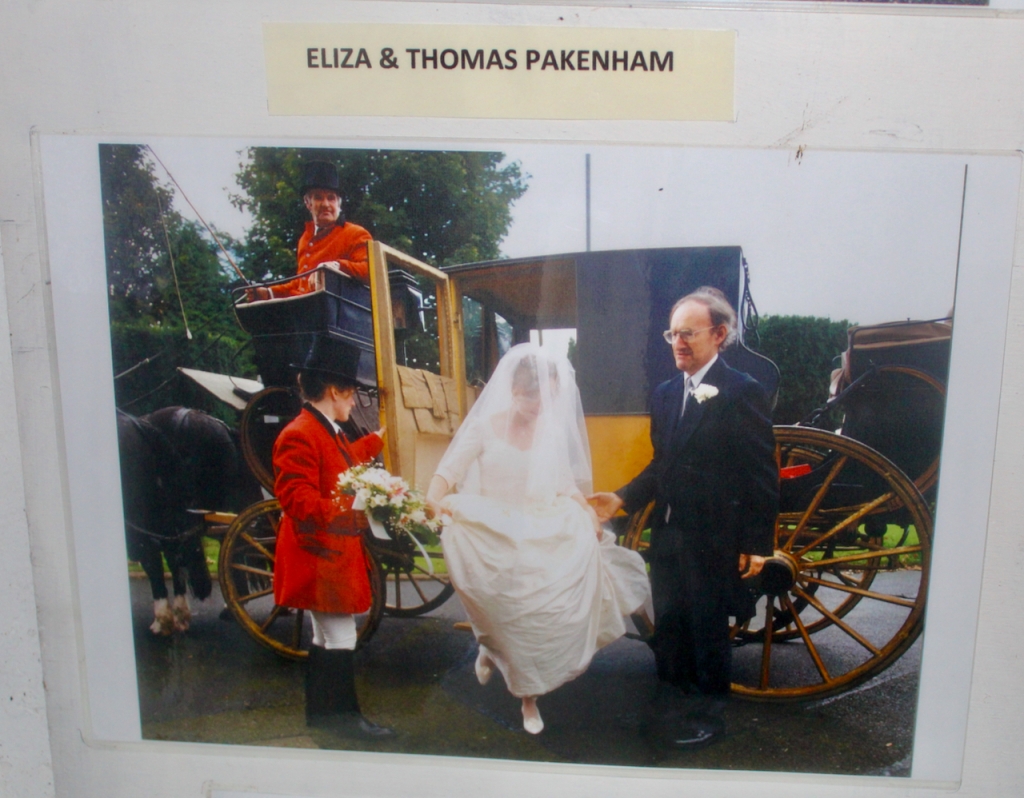

Edward Michael Pakenham 2nd Baron Longford and his wife Catherine née Rowley had many children. Their daughter Catherine (1773-1831) married Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, but it was an unhappy marriage. The daughter of the current occupant of Tullynally Thomas Pakenham and his wife Valerie, Eliza Pakenham, published Tom, Ned and Kitty: An Intimate History of an Irish Family, about the Duke of Wellington and the family’s relation to him. Kitty fell for the local naval man, Arthur Wellesley, but the family refused to let her marry him. He promised her that he would return and marry her. He went off to sea, and she was brokenhearted. He returned as the Duke of Wellington and did indeed marry her. He, however, was not a very nice man, and is reported to have said loudly as she walked up the aisle of the church to marry him, “Goodness, the years have not been kind.”

When Edward died in 1792 his son Thomas (1774-1835) inherited, and became the 3rd Baron Longford. When his grandmother Elizabeth née Cuffe, who had been made the Countess of Longford in her own right, died in 1794, Thomas became 2nd Earl of Longford.

Tullynally was gothicized by Francis Johnston to become a castle.

We came across Francis Johnson (1760-1829) the architect when I learned that he had been a pupil of Thomas Cooley, the architect for Richard Robinson, Archbishop of Armagh (who had Rokeby Hall in County Louth built as his home). Johnston took over Cooley’s projects when Cooley died and went on to become an illustrious architect, who designed the beautiful Townley Hall in County Louth which we visited recently. He also enlarged and gothicized Markree Castle for the Coopers, and Slane Castle for the Conynghams. His best known building is the General Post Office on O’Connell Street in Dublin. We recently saw his house in Dublin on Eccles Street, on a tour with Aaran Henderson of Dublin Decoded.

Thomas the 2nd Earl sat in the British House of Lords as one of the 28 original Irish Representative Peers. Casey and Rowan call Francis Johnston’s work on the house “little more than a Gothic face-lift for the earlier house.” He produced designs for the house from 1794 until 1806. On the south front he added two round towers projecting from the corners of the main block, and battlemented parapets. He added the central porch. To the north, he built a rectangular stable court, behind low battlemented walls. He added thin mouldings over the windows, and added the arched windows on either side of the entrance porch.

Terence Reeves-Smyth details the enlargement of Tullynally in his Big Irish Houses:

“Johnson designed battlements and label mouldings over the windows, but as work progressed it was felt this treatment was too tame, so between 1805 and 1806 more dramatic features were added, notably round corner turrets and a portcullis entrance, transforming the house with characteristic Irish nomenclature from Pakenham Hall House to Pakenham Hall Castle.”

“During the early nineteenth century, a craze for building sham castles spread across Ireland with remarkable speed, undoubtedly provoked by a sense of unease in the aftermath of the 1798 rebellion. Security was certainly a factor in Johnson’s 1801 to 1806 remodelling of Tullynally, otherwise known as Pakenham Hall, where practical defensive features such as a portcullis entrance were included in addition to romantic looking battlements and turrets. Later enlargements during the 1820s and 1830s were also fashioned in the castle style and made Tullynally into one of the largest castellated houses in Ireland – so vast, indeed, that it has been compared to a small fortified town.”

Thomas married Georgiana Emma Charlotte Lygon, daughter of William Lygon, 1st Earl Beauchamp (UK) in 1817. He was created 1st Baron Silchester, County Southampton [U.K.] on 17 July 1821, which gave him and his descendants an automatic seat in the House of Lords.

According to Rowan and Casey it may have been his wife Georgiana Lygon’s “advanced tastes” that led to the decision to make further enlargements in 1820. They chose James Sheil, a former clerk of Francis Johnston, who also did similar work at Killua Castle in County Westmeath, Knockdrin Castle (near Mullingar) and Killeen Castle (near Dunshaughlin, Co. Meath).

At Tullynally Sheil added a broad canted bay window (a bay with a straight front and angled sides) towards the north end of the east front, with bartizan turrets (round or square turrets that are corbelled out from a wall or tower), and wide mullioned windows under label mouldings (or hoodmouldings) in the new bay.

Sheil also decorated the interior. We shall now go inside to take a look.

We entered through the big red door in the entrance porch.

One enters into a large double height hall. It is, Terence Reeves-Smyth tells us, 40 feet square and 30 feet high. I found it impossible to capture in a photograph. It has a Gothic fan vaulted ceiling, and is wood panelled all around, with a fireplace on one side and an organ in place of a fireplace on the other side.

The hall, Casey and Rowan tell us, has a ceiling of “prismatic fan-vaults, angular and overscaled, with the same dowel-like mouldings marking the intersection of the different planes…The hall is indeed in a very curious taste, theatrical like an Italian Gothick stage set, and rendered especially strange by the smooth wooden wainscot which completely encloses the space and originally masked all the doors which opened off it.” [6] As this smooth wainscot and Gothic panelled doors are used throughout the other main rooms of the house and are unusual for Sheil, this is probably a later treatment.

Terence Reeves-Smyth describes the front hall:

“Visitors entering the castle will first arrive in the great hall – an enormous room forty-feet square and thirty feet high with no gallery to take away from its impressive sense of space. A central-heating system was designed for this room by Richard Lovell Edgeworth, who earlier in 1794 had fitted up the first semaphore telegraph system in Ireland between Edgeworthstown and Pakenham Hall, a distance of twelve miles. In a letter written in December 1807, his daughter Maria Edgeworth, a frequent visitor to Pakenham Hall, wrote that “the immense hall is so well warmed by hot air that the children play in it from morning to night. Lord L. seemed to take great pleasure in repeating twenty times that he was to thank Mr. Edgeworth for this.” Edgeworth’s heating system was, in fact, so effective that when Sheil remodelled the hall in 1820 he replaced one of the two fireplaces with a built-in organ that visitors can still see. James Sheil was also responsible for the Gothic vaulting of the ceiling, the Gothic niches containing the family crests, the high wood panelling around the base of the walls and the massive cast-iron Gothic fireplace. Other features of the room include a number of attractive early nineteenth century drawings of the castle, a collection of old weapons, family portraits and an Irish elk’s head dug up out of a bog once a familiar feature of Irish country house halls.” [see 1]

There is a long vaulted corridor that runs through the house at first-floor level which Rowan and Casey write is probably attributable to Sheil.

From the Great Hall we entered the dining room, which used to be the staircase room.

The dining room, drawing room and library were all decorated in Sheil’s favoured simple geometrical shaped plasterwork of squares and octagons on the ceiling. [6]

We can see that the windows in the dining room are in the canted bow which was added by James Shiel. The room is hung with portraits of family members. The ceiling drops at the walls into Gothic decoration of prismatic fan-vaults with dowels similar to those in the Hall, though less detailed.

Georgina née Lygon, wife of the 2nd Earl, was well-read and wealthy. She and her husband were friendly with the Edgeworths of nearby Edgeworthstown. She was responsible for developing the gardens, planting the trees which are now mature, and creating a formal garden. Her husband died in 1835 but she lived another forty-five years, until 1880. She and her husband had at least eight children. Their son Edward Michael Pakenham (1817-1860) succeeded to become 3rd Earl of Longford in 1835 while still a minor.

We then went to the library. The library was started by Elizabeth Cuffe, wife of the the 1st Baron Longford, and continued by Georgiana, wife if the 2nd Earl. Again, it’s hard to capture in a photograph, while also being on a tour.

The portrait over the fireplace in the library is Major General Edward Michael Pakenham (1778-1815), brother of the 2nd Earl of Longford. Major General Pakenham (whose sword in the red sheath is in the front Hall) was killed in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, between Britain and the United States of America, in the “War of 1812.”

Another brother of the 2nd Earl of Longford was Lieutenant General Hercules Pakenham (1781-1850). He married Emily Stapleton, daughter of Thomas Stapleton, 13th Lord le Despenser, 6th Baronet Stapleton, of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean. Hercules inherited Langford Lodge in County Antrim, from his mother Catherine Rowley (it no longer exists). Hercules served as MP for Westmeath.

A selection of books by the prolific Pakenham family are on the table in the library.

We next visited the drawing room.

When he reached his majority, the third Earl, Edward Michael, who was called “Fluffy,” along with his mother, made further enlargements from 1839-45 with two enormous wings and a central tower by another fashionable Irish architect, Sir Richard Morrison. The wings linked the house to the stable court which had been built by Francis Johnston. The addition included the large telescoping octagonal tower.

Terence Reeves-Smyth writes:

“More substantial additions followed between 1839 and 1846 when Richard Morrison, that other stalwart of the Irish architectural scene, was employed by the Dowager Countess to bring the house up to improved Victorian standards of convenience. Under Morrison’s direction the main house and Johnson’s stable court were linked by two parallel wings both of which were elaborately castellated and faced externally with grey limestone. Following the fashion recently made popular by the great Scottish architect William Burn, one of the new wings contained a private apartment for the family, while the other on the east side of the courtyard contained larger and more exactly differentiated servants’ quarters with elaborate laundries and a splendid kitchen.”

Casey and Rowan describe Morrison’s work: “On the entrance front the new work appears as a Tudoresque family wing, six bays by two storeys, marked off by tall octagonal turrets, with a lower section ending in an octagonal stair tower which joins the stable court. This was refaced and gained a battlemented gateway in the manner of the towers that Morrison had previously built as gatehouses at Borris House, County Carlow [see my entry on Borris House] and Glenarm Castle, County Antrim. The entrance porch, a wide archway in ashlar stonework, with miniature bartizans rising from the corners, was also rebuilt at this time. Though Morrison provided a link between the old house and the family wing by building a tall octagonal tower, very much in the manner of Johnston’s work at Charleville Forest, County Offaly [see my entry Places to visit and stay in County Offaly], the succession of facades from south to north hardly adds up to a coherent whole. The kitchen wing, which forms an extension of the east front, is much more convincingly massed, with a variety of stepped and pointed gables breaking the skyline and a large triple-light, round-headed window to light the kitchen in the middle of the facade.“

On the tour, our guide told us of the various additions. She told us that “Fluffy” lived with his mother and chose to follow the fashion of living in an apartment in a wing of the house.

We explored these wings further on the tour of the “downstairs” servants area.

The courtyard created by the Morrison wings is very higgeldy piggeldy.

On the “downstairs tour” we toured the wings of the castle that had been added by Fluffy and his mother. A wing was built for the staff, and it was state of the art in the 1840s when Richard Morrison built these additions. Fluffy never married, and unfortunately died in “mysterious circumstances” in a hotel in London.

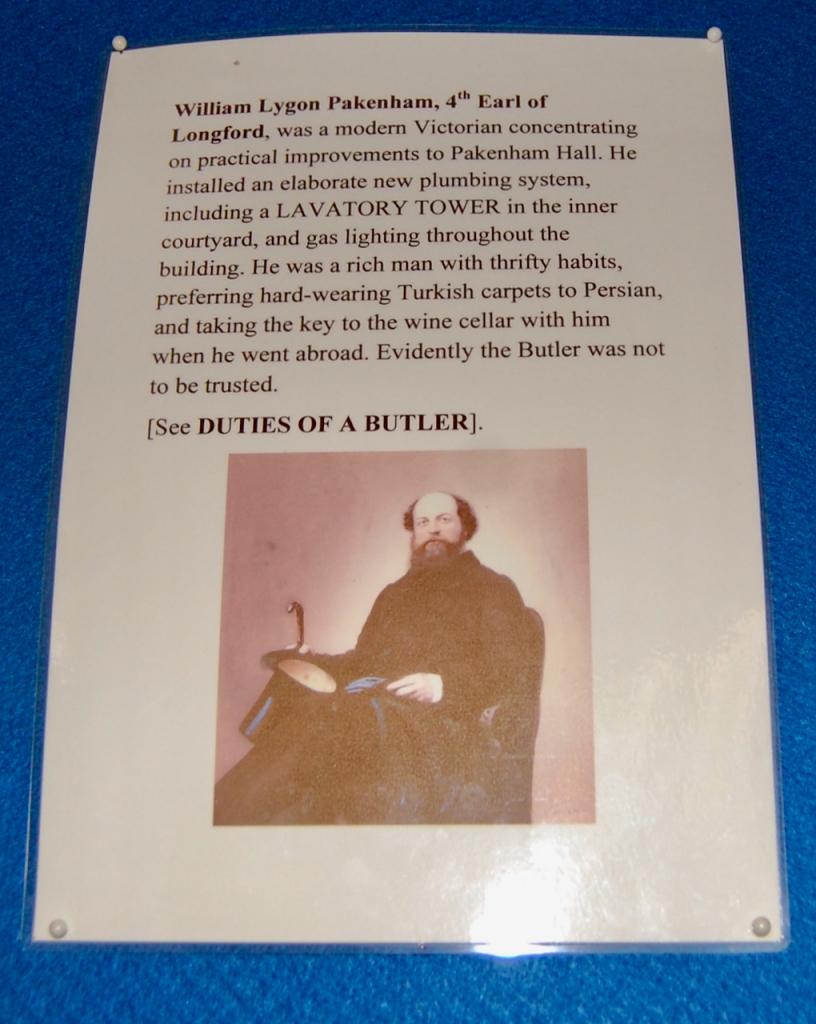

When Fluffy died his brother William (1819-1887), an army general in the Crimean War and long-serving military man, became the 4th Earl of Longford.

Terence Reeves-Smyth continues:“After the third Earl’s death in 1860 his brother succeeded to the title and property and proceeded to modernise the castle with all the latest equipment for supplying water, heat and lighting. Except for a water tower erected in the stable court by the Dublin architect J. Rawson Carroll in the 1860s, these modifications did not involve altering the fabric of the building, which has remained remarkably unchanged to the present day.”

The further additions in 1860 are by James Rawson Carroll (d.1911), architect of Classiebawn, Co Sligo, built for Lord Palmerston and eventually Lord Mountbatten’s Irish holiday home in the 1860s.

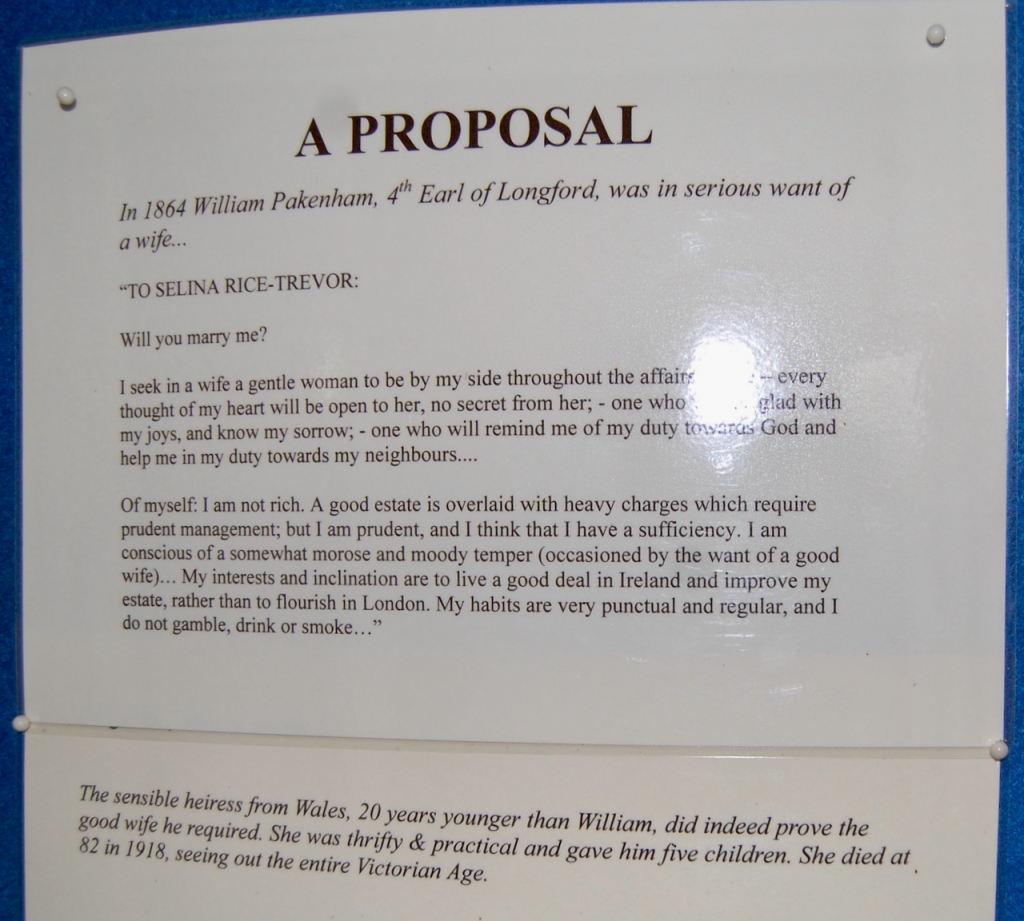

The 4th Earl married Selina Rice-Trevor from Wales in 1862. Her family, our guide told us, “owned most of Wales.” His letters and a copy of his diary from when he arrived home from the Crimean War are all kept in Tullynally.

We can even read his proposal to Selina:

William the 4th Earl installed a new plumbing system. He also developed a gas system, generating gas to light the main hall. The gas was limited, so the rest of the light was provided by candles, and coal and peat fires. His neighbour Richard Lovell Edgeworth provided the heating system.

The next generation was the 5th Earl, son of the 4th Earl, Thomas Pakenham (1864-1915). He was also a military man. He married Mary Julia Child-Villiers, daughter of Victor Albert George Child-Villiers, 7th Earl of Island of Jersey and they had six children.

The family are lucky to have wonderful archives and diaries. Mary Julia Child-Villiers was left a widow with six children when her husband died during World War I in Gallipoli. The downstairs tour shows extracts from the Memoir of Mary Clive, daughter of the 5th Earl of Longford.

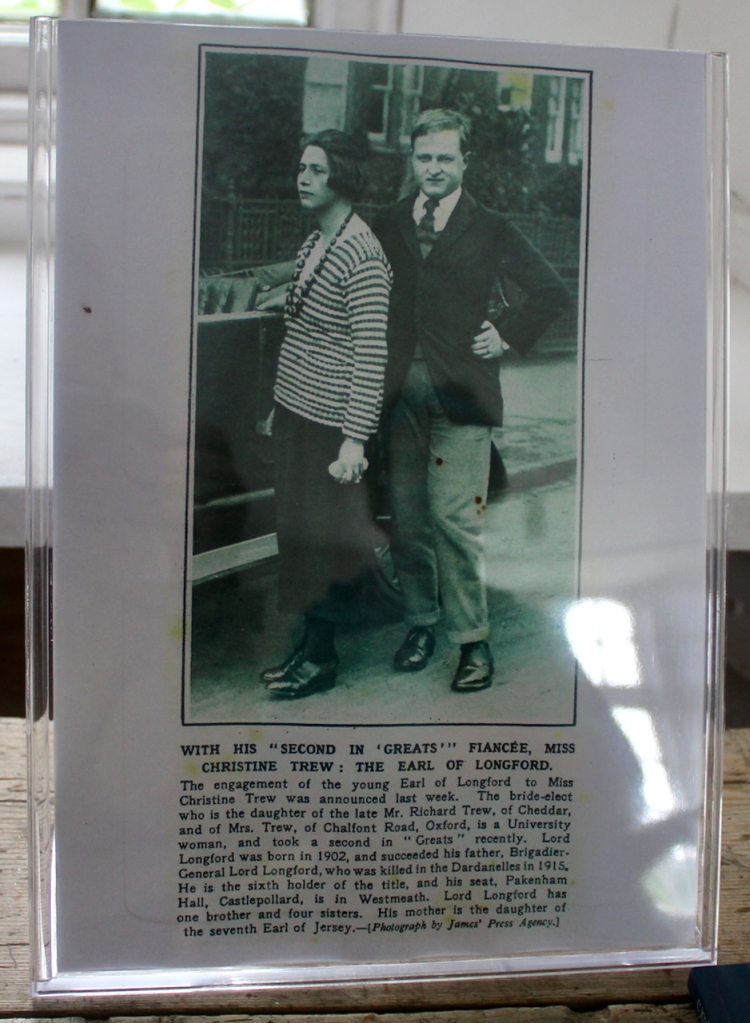

Since 1915 the family have been writers (before that, they were mostly military). Edward the 6th Earl (1902-1961) was a prolific playwright who restored the Gate Theatre in Dublin and taught himself Irish, and with his wife Christine, created the Longford Players theatrical company which toured Ireland in the 30s and 40s. He served as a Senator for the Irish state between 1946 and 1948.

His sister Violet Georgiana, who married Anthony Dymoke Powell, wrote many books, and her husband was a published writer as well. Another sister, Mary Katherine, who married Major Meysey George Dallas Clive, also wrote and published. Their sister Margaret Pansy Felicia married a painter, Henry Taylor Lamb, and she wrote a biography of King Charles I.

A brother of Edward, Frank (1905-2001), who became the 7th Earl after Edward died in 1961, and his wife Elizabeth née Harman, wrote biographies, as did their children, Antonia Fraser, Rachel Billington and Thomas Pakenham the 8th Earl of Longford. Antonia Fraser, who wrote amongst other things a terrific biography of Marie Antoinette and another wonderful one of King Charles II of England, is one of my favourite writers. She is a sister of the current Earl of Longford, Thomas, who lives in the house. They did not grow up in Tullynally, but in England. Thomas’s wife Valerie has published amongst other books, The Big House in Ireland.

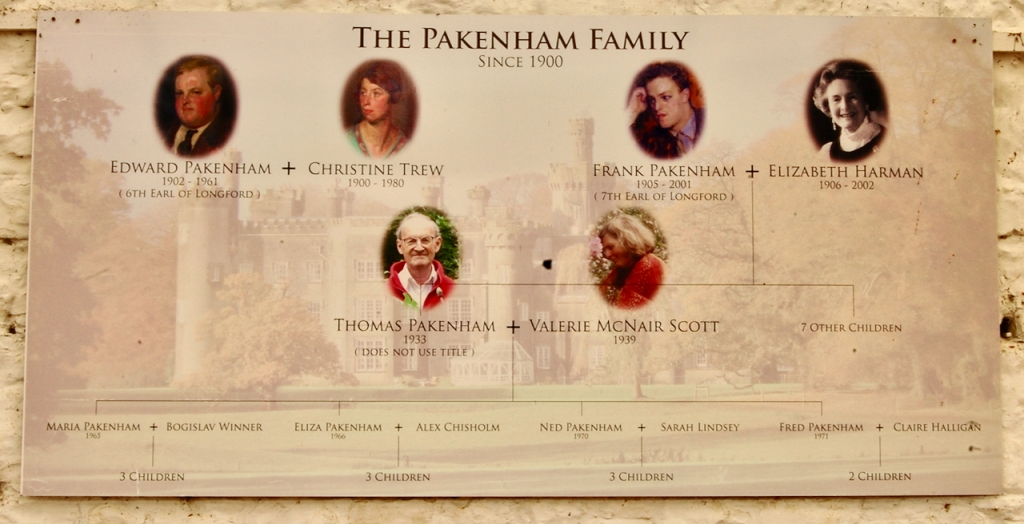

There was a handy chart of the recent family on the wall in the courtyard café:

Stephen noted with satisfaction that Thomas Pakenham does not use his title, the 8th Earl of Longford. That makes sense of course since such titles are not recognised in the Republic of Ireland! In fact Stephen’s almost sure that it is against the Irish Constitution to use such titles. This fact corresponds well with the castle’s change in name – it was renamed Tullynally in 1963 to sound more Irish.

When we visited in 2020 we purchased our tickets in the café and had time for some coffee and cake and then a small wander around the courtyard and front of the Castle. One enters the stable courtyard, designed by Francis Johnston, to find the café and ticket office.

I didn’t get to find out what is in every tower and behind every window, and I suspect it’s a place to get to know by degrees!

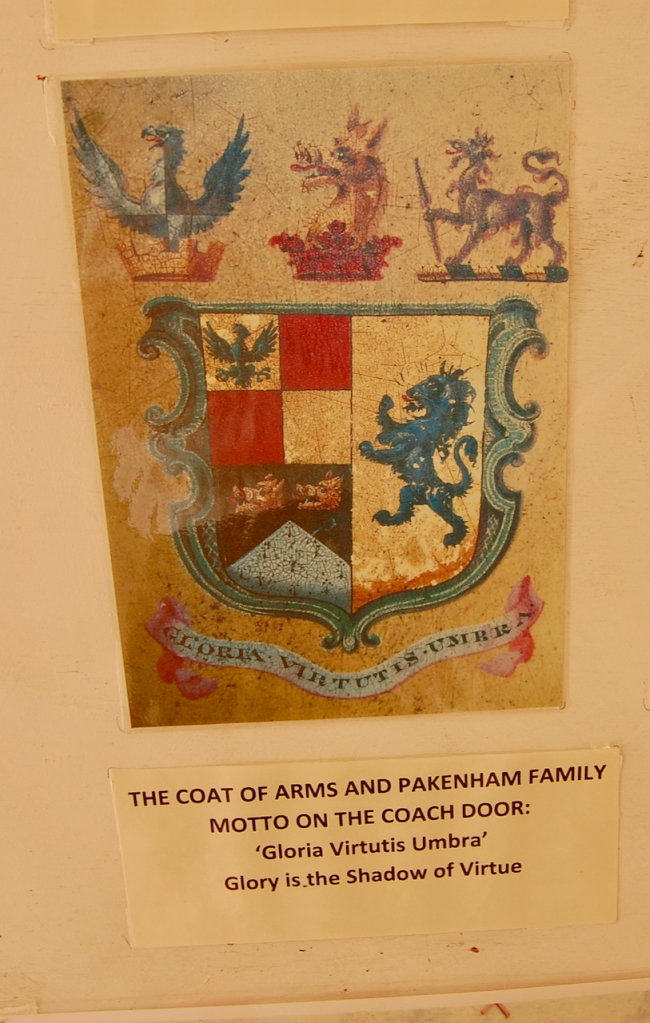

The coach was passed down to Olive Pakenham-Mahon of Strokestown, Roscommon (another section 482 property, see my entry), who was Dean Henry’s great granddaughter. Olive sold it to her cousin Thomas Pakenham, the present owner of Tullynally. It was restored by Eugene Larkin of Lisburn, and in July 1991 took its first drive in Tullynally for over a hundred years. Family legend has it that the coach would sometimes disappear from the coachhouse for a ghostly drive without horses or coachman! It was most recently used in 1993 for the wedding of Eliza Pakenham, Thomas’s daughter, to Alexander Chisholm.

The tour brought us through the arch from the first courtyard containing the café, into a smaller, Morrison courtyard.

Richard Morrison spent more time working on the laundry room than on any other part of the house.

It was at this time that the “dry moat” was built – it was not for fortification purposes but to keep the basements dry.

Our guide described the life of a laundress. After the installation of the new laundry, water was collected in a large watertank, and water was piped into the sinks into the laundry.

A laundry girl would earn, in the 1840s (which is during famine time), €12/year for a six day week, and start at about fourteen years of age. A governess would teach those who wanted to learn, to read and write, so that the girls could progress up in the hierarchy of household staff. There was even a servants’ library. This was separate of course from the Pakenham’s library, which is one of the oldest in Ireland. There was status in the village to be working for Lord Longford, as he was considered to be a good employer. His employees were fed, clothed in a uniform, housed, and if they remained long enough, even their funeral was funded. There was a full time carpenter employed on the estate and he made the coffins.

The laundry girls lived in a world apart from household staff. They ate in the laundry. Their first job in the morning would be to light the fire – you can see the brick fireplace in the first laundry picture above. A massive copper pot would be filled with water, heated, and soap flakes would be grated into the pot. The laundry girls would do the washing not only for their employers but also for all of the household staff – there were about forty staff in 1840. As well as soap they would use lemon juice, boiled milk and ivy leaf to clean – ivy leaves made clothes more black. The Countess managed the staff, with the head housekeeper and butler serving as go-between.

William, the 4th Earl of Longford, had a hunting lodge in England and since he had installed such a modern laundry in Tullynally, he would ship his laundry home to Pakenham Hall be washed!

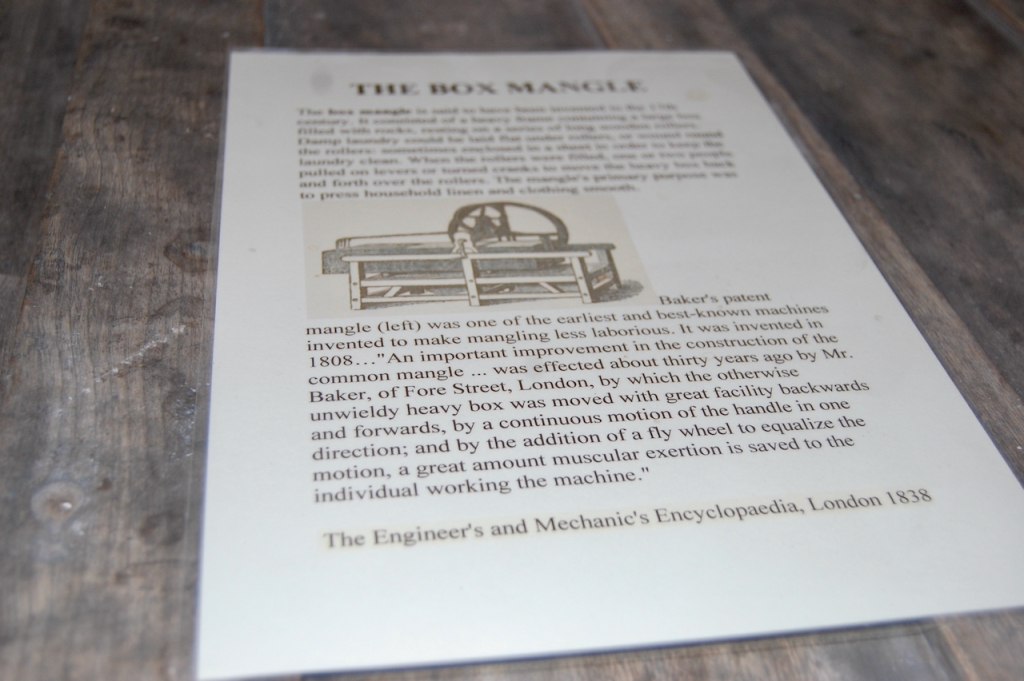

Next, the washing would be put through the mangle.

The girls might have to bring laundry out to the bleaching green. A tunnel was installed so that the girls avoided the looks and chat of the stable boys, or being seen by the gentry. William also developed a drying room. Hot water ran through pipes to heat the room to dry the clothes.

There was also an ironing room.

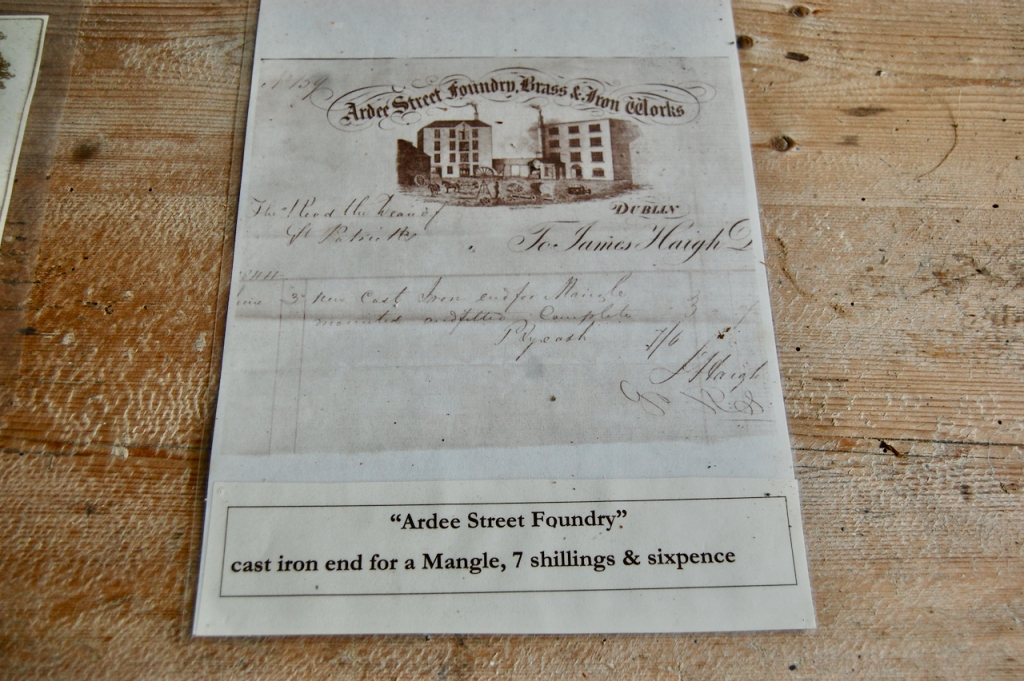

The next room was a small museum with more information about the castle and family, and included a receipt for the iron end of a mangle, purchased from Ardee Street Foundry, Brass and Iron Works, Dublin. We live near Ardee Street!

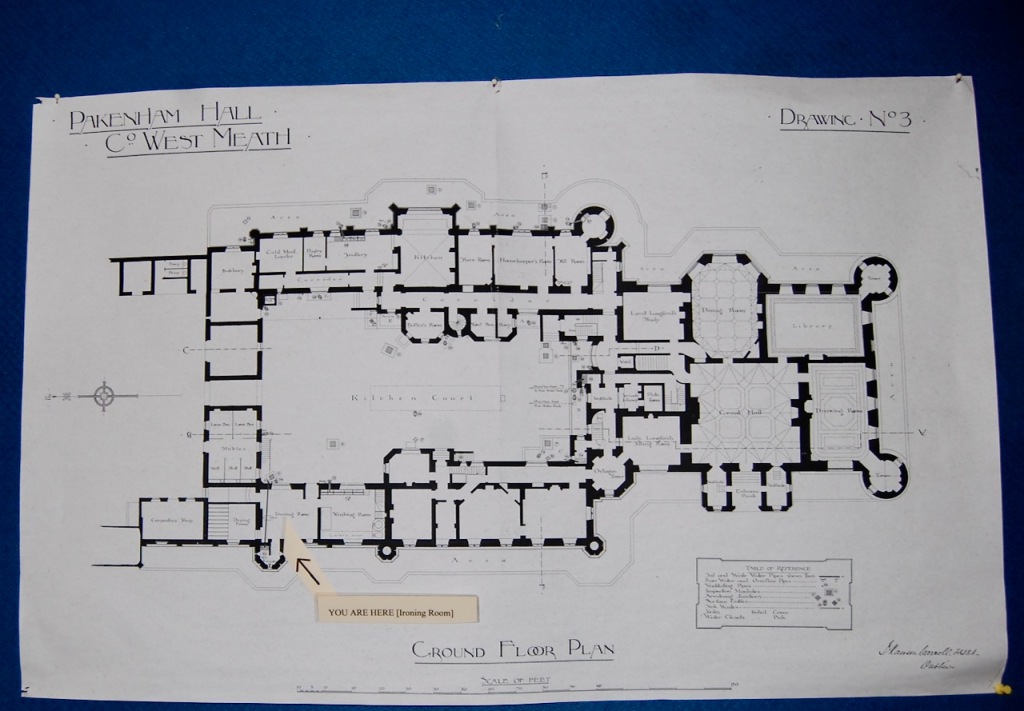

This information board tells us details about the staff, as well as giving the layout of the basement:

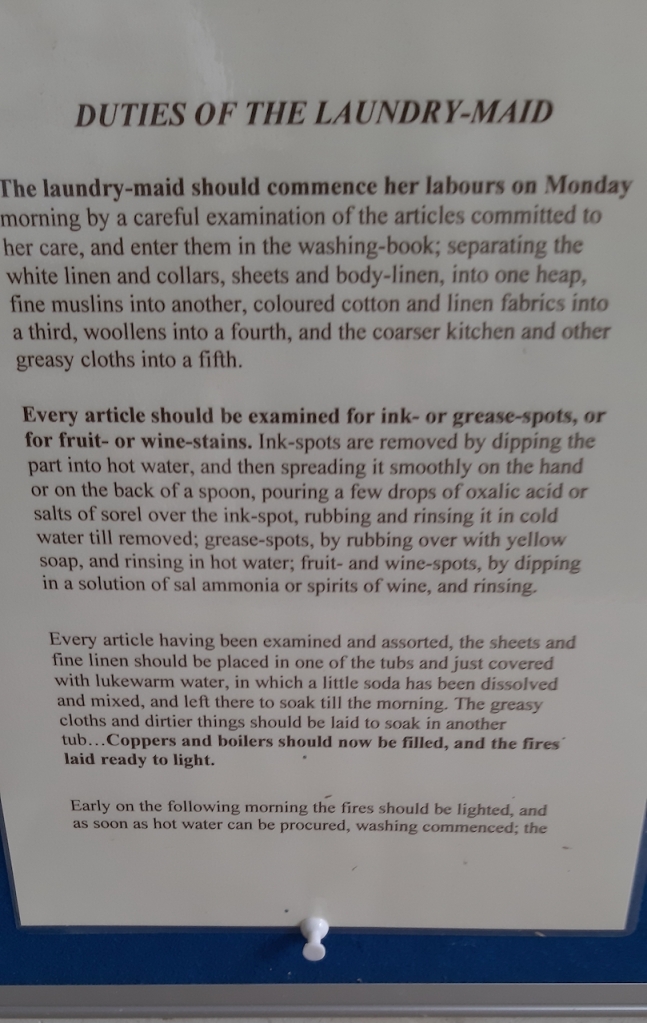

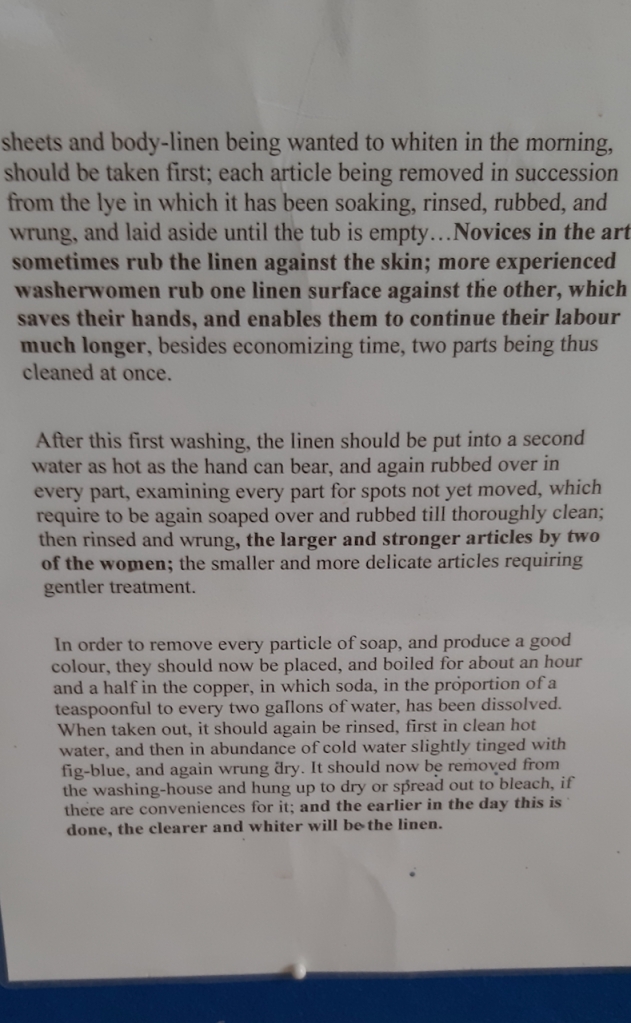

By 1860 Pakenham Castle was run in the high Victorian manner. The Butler and Housekeeper managed a team of footmen, valets, housemaids and laundry maids, whilst Cook controlled kitchen maids, stillroom maid and scullery maids. A stillroom maid was in a distillery room, which was used for distilling potions and medicines, and where she also made jams, chutneys etc. There was also a dairy, brewery and wine cellar. The Coachman supervised grooms and stable boys, while a carpenter worked in the outer yard and a blacksmith in the farmyard. Further information contains extracts from Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1859), detailed duties of a housemaid, a laundry-maid, and treatment of servants. The estate was self-sufficient. Staff lived across the courtyard, with separate areas for men and women. There were also farm cottages on the estate. Servants for the higher positions were often recruited by word of mouth, from other gentry houses, and often servants came from Scotland or England, and chefs from France.

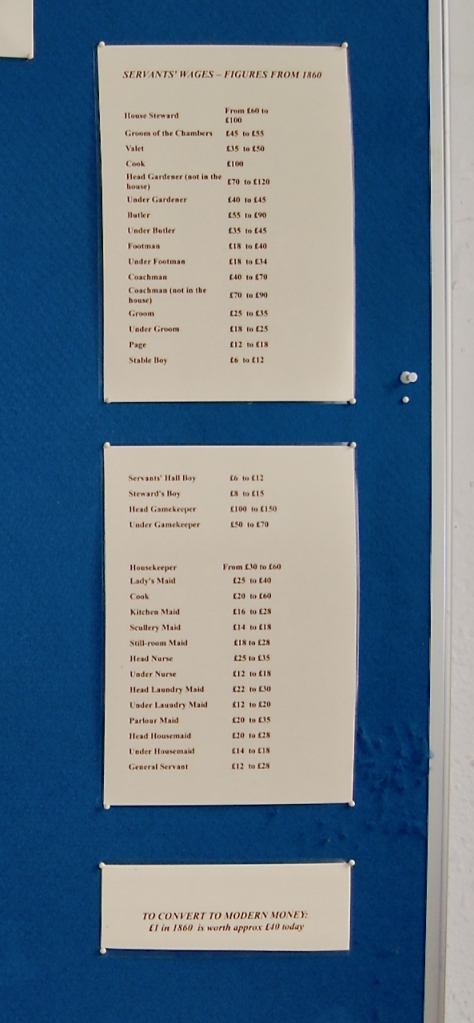

We are also given the figures for servants’ wages in 1860.

Next, we headed over toward the kitchen. On the way we passed a water filter system, which was a ceramic jar containing an asbestos and charcoal filter system. However, staff were given beer to drink as it was safer at the time than water. We saw a container used to bring food out to staff in the fields – the food would be wrapped in hay inside the container, which would hold in the heat and even continue to cook the food. We stopped to learn about an ice chest:

The ice chest would be filled with ice from the icehouse. We were also shown the coat of a serving boy, which our tour guide had a boy on the tour don – which just goes to show how young the serving boys were:

A serving boy wearing this uniform would carry dishes from the kitchen to the dining room, which was as far from the kitchen as possible to prevent the various smells emanating from the kitchen from reaching the delicate nostrils of the gentry. The serving boy would turn his back to the table, and watch mirrors to see when his service was needed at the table, under the management of the butler. Later, when the ladies had withdrawn to the Drawing Room, to leave the men to drink their port and talk politics, the serving boy would produce “pee pots” from a sideboard cupboard, and place a pot under each gentleman! Our guide told us that perhaps, though she is not sure about this, men used their cane to direct the stream of urine into the pot. The poor serving boy would then have to collect the used pots to empty them. Women would relieve themselves behind a screen in the Drawing Room.

In the large impressively stocked kitchen, we saw many tools and implements used by the cooks. Richard Morrison ensured that the kitchen was filled with light from a large window.

This kitchen was used until around 1965. The yellow colour on the walls is meant to deter flies. Often a kitchen is painted in blue either, called “Cook’s blue,” also reputed to deter flies. Because this kitchen remained in continuous use its huge 1875 range was replaced by an Aga in the 1940s.

The cookware is made of copper, and you can see by the stove a large ceramic vessel topped with muslin for straining jams.

Candles were made from whale blubber. Candles made from blubber closer to the whale’s head were of better quality.

The housekeeper would have her own room, which our guide told us, was called the “pug room” due to the, apparently, sour face of of the housekeeper, but also because she often kept a pug dog!

Next we were taken to see Taylor’s room. Taylor was the last Butler of the house. We passed an interesting fire-quenching system on the way.

Next, the tour guide took us to see the servants’ staircase and set of bells. We passed the mailbox on the way:

This would normally be the end of the tour, but since we were such a fascinated, attentive group, the guide took us into the basement to see the old servants’ dining hall.

The gardens, covering nearly 30 acres, were laid out in the early 19th century and have been restored. They include a walled flower garden, a grotto and two ornamental lakes.

Here is the description of the gardens, from the Irish Historic Houses website:“The gardens, illustrated by a younger son in the early eighteenth century, originally consisted of a series of cascades and formal avenues to the south of the house. These were later romanticised in the Loudonesque style, with lakes, grottoes and winding paths, by the second Earl and his wife [Thomas (1774-1835) and Georgiana Lygon (1774-1880)]. They have been extensively restored and adapted by the present owners, Thomas and Valerie Pakenham, with flower borders in the old walled gardens and new plantings of magnolias, rhododendron and giant lilies in the woodland gardens, many collected as seed by Thomas while travelling in China and Tibet. He has recently added a Chinese garden, complete with pagoda, while the surrounding park contains a huge collection of fine specimen trees.” [7]

I befriended the resident cat.

Goodbye Tullynally! I look forward to visiting again.

[1] Reeves-Smyth, Terence. Big Irish Houses. Appletree Press Ltd, The Old Potato Station, 14 Howard Street South, Belfast BT7 1AP. 2009

[2] p. 525. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

[3] p. 135. Great Houses of Ireland. Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes. Laurence King Publishing, London, 1999.

[4] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/search/label/County%20Westmeath%20Landowners

[6] p. 527. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

[7] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Tullynally%20Castle

This land should never have been given to unentitled British imperliests. And certainly should not be still be in in their hands. This family like all “royalty” at the time had a deluded sense of entitlement and superiority. They we’re waited on hand and foot while countless died during the famine. Take back what is genuinely Irish not British. This british family never had and never should have had any “entitlement” to this misappropriated land. How we’re these sleazy,pompous theives allowed to keep their ill gotten gains,particularly after irelands independence from such tyranny.

LikeLike

It’s interesting to study history to see how various areas were fought over and taken over. I like to try to understand in more detail. I hope this website gives a nuanced picture of the relationship between landed families and their neighbours. I sympathise with your anger. On the other hand, big houses provided employment, like the Intels and Googles of our day. There are still people dying of famine today. Ireland wasn’t a peaceful place before the Normans came and there were always rich and poor people.

LikeLike

As a descendant of Anglo-Irish aristocracy, and someone who considers themselves as Irish, I think it is important to note to some hardline nationalistic Irish, that the majority of Irish landed gentry, whether Protestant or Catholic treated their staff with respect. Many Protestant landowners were involved with the fight for Irish home rule and stood together with Catholics against the British Government and spoke out against the absent landowners who showed no interest in Ireland or their staff. I remember a nice Catholic neighbour cursing the IRA for burning down Lord Bandon’s house and thus putting her father who worked on the estate out of work. After this event, her family lived in poverty.

LikeLike