www.corravahan.com

Open dates in 2024: Jan 4-5, 11-12, 18-19, 25-26, Feb 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, 22-23, 29, Mar 1, 7-8, May 2-4, 9-11, 16-18, 23-25, 30-31, June 1, 6-8, 13-15, 20-22, 27-29, July 4-6, Aug 16-25, 9am-1pm, Sundays, 2pm-6pm

Tours on the hour, or by appointment.

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student/child €5

CCTV in operation.

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

This house is a delight! The owners, the Elliotts, who purchased the house in 2003, appreciate the intricacies of the house and its history, and convey this with enthusiasm. Corravahan House has an excellent website which describes the history of the house and its occupants, along with photographs from former days.

Ian Elliott obliged us by opening on a day not normally scheduled. Visits are further curtailed by Covid-19 restrictions and distancing and safety requirements. I appreciate when anyone is willing to accommodate a visit this year.

We drove to the house on our way to Donegal to visit Stephen’s mother. We stopped a night in Monaghan, so had plenty of time for our visit. Unfortunately it was raining so we didn’t get to see the gardens – we will have to visit another time!

The National Inventory of Historic Architecture tells us that Corravahan House is an Italianate style three-bay three-storey over basement former rectory, built 1841. It has a one-storey projecting entrance porch to the front, containing a four-panelled timber door. The Inventory website also mentions “glazed tripartite loggia” and the bow on the rear elevation.

The Inventory notes the slate roof “with oversailing eaves” and the cornice on the chimneystacks. The garden facing walls are of “random rubble” with large corner stones at the rear elevation, and other walls have been rendered.

On the garden elevation, there is a Wyatt window with plain stone mullions and projecting cornice under red-brick relieving arch, and brick dressings to window openings on upper floors, garden front.

The Inventory mentions the “ruled-and-lined rendered walls.” Ian pointed this out to us inside the timber lean-to. One can see the original wall, and the lines hand-drawn. The lines are to make the rendered wall appear to be made of stone blocks! We can see a clearer, more recent example of this on a new structure built in the yard, but again, more on this later.

The windows in the bow have curved sashes and timber, although the glass in the windows is flat. These windows would be particularly difficult to craft, to fit the curve of the bowed wall.

Ian greeted us, along with a friendly dog. We stepped into the porch, which has four-over-four timber sash windows to the sides. A further door leads into the entrance hall.

The house was built for a clergyman, Marcus Gervais Beresford (1801-1885). Before he had this house built, he rented nearby as he was the Vicar for Drung, appointed by his father in 1828. The previous parsonage had been condemned as unfit for use. Reverend Marcus Beresford was the great-grandson of Marcus Beresford, the 1st Earl of Tyrone (1694-1763), whom we came across when we visited Curraghmore in County Waterford (the husband of Catherine, who built the Shell House). The 1st Earl’s son John, an MP for County Waterford, was Marcus Gervais’s grandfather, and John’s son, George (1765-1841), Marcus Gervais’s father, became Bishop for Kilmore, County Cavan. Bishop George Beresford married Frances, a daughter of Gervase Parker Bushe and Mary Grattan (a sister of Henry Grattan (1746-1820), the politician and lawyer who supported Catholic emancipation) [2]. Marcus Gervais followed in his father’s footsteps, and as the third son, joined the Church.

The website for Corravahan tells us that the Beresfords engaged the services of the architect William Farrell, who had recently completed the new See House at Kilmore for Bishop George, to construct Corravahan as the new rectory for the parish. According to Wikipedia, William Farrell was a Dublin-based Irish architect who was the “Board of First Fruits” architect for the Church of Ireland ecclesiastical province of Armagh from 1823-1843. In this time he designed several Church of Ireland churches, as well as houses for the clergy. He built several houses in County Cavan, including Rathkenny [ca. 1820] and Tullyvin [built ca 1812], Shaen House in Laois (now a hospital), Clonearl House in County Offaly, and Clogrennan House in County Carlow.

Due to the family’s connections and status, the house was designed to impress. It is the details that indicate its quality, and visitors who were meant to be impressed would have recognised the signs. The National Inventory of Architectural Heritage lists some of the details – for example: “Entrance hall has decorative timber panelled walls set in round headed arch recesses with panelled pilasters having squared Doric entablature. Flooring of decorative black and white tiles mimicking Italian marble.”

The vestibule is Grecian Classical in style. The arches are of plaster. Ian reckons the floor tiles are Portland stone – a stone of particularly good quality – and a darker limestone, perhaps Kilkenny marble. You can see in the photograph the quality craftsmanship of the wood panelling on the walls. And this is just the front hall! A door to the right leads into what would have been the Vicar’s office where he would meet his parishioners. Guests to be entertained would enter straight ahead into the main part of the house.

We entered a room that is now the library. It is the second library of the house. The first room, the Bishop’s office, was the first library. A later resident of the house, Charles Robert Leslie, became wheelchair bound and an elevator was installed into the house where the first library had been, so a second room was converted into a library, which had previously been the morning room. A window was covered over with bookcases, which is still visible from the outside of the house.

Marcus Beresford followed in his father’s footsteps and was appointed Bishop of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh in 1854. He moved out of Corravahan, and the next Vicar of Drung moved in, the Reverend Charles Leslie (1810-1870).

This Charles Leslie’s father, John (1772-1854), was the son of Charles Powell Leslie I, whom we came across when we visited Castle Leslie in County Monaghan. John was Charles Powell Leslie’s second son, and since he was not to inherit Castle Leslie, he joined the Church.

Reverend John Leslie (1772-1854) rose quickly due to his connections, and became Bishop of Dromore in 1812 and Bishop of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh in 1841. He married the daughter of the Bishop of Ross, Isabella St. Lawrence, from the Howth Castle family of St. Lawrences (her grandfather was the 1st Earl of Howth. The castle was still in private hands, until sold by the Gaisford-St. Lawrence family in 2019. I would love to see it!). He preceded Marcus Beresford as Bishop of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh. His eldest son, Charles became vicar of Drung in 1855. He moved into Corravahan with his wife and children (or as they liked to call it, “Coravahn.” [3] Their only daughter, Mary, died shortly afterwards, aged just 15.

Charles Leslie married, first, Frances King, daughter of General Robert Edward King, 1st Viscount Lorton of Boyle, County Roscommon, and his wife Frances Parsons (daughter of the 1st Earl of Rosse, the family who own Birr Castle, County Offaly, another section 482 property), in 1834. After she died, childless, he married Louisa Mary King, daughter of Lt-Col Henry King, 1st cousin of his first wife. The Corravahan website tells us that in 1836, Charles went on a tour of Europe with the Viscount and some members of his family, including his late wife’s cousin, Louisa, who he would marry the following year.

Charles Leslie continued to serve as the Vicar of Drung until 1870. He was then appointed, following in the footsteps of his father and of the former resident of Corravahan Reverend Marcus Beresford, Bishop of Kilmore. He died, however, three months after his appointment and so never moved from Corravahan. Following his death, his widow and five sons retained the house as a private residence, while providing a new, more modest rectory for the parish on nearby land. This house is also listed in the National Inventory of Historic Architecture, as Drung Rectory. The entry incorrectly states that it no longer serves as a rectory. It does in fact still serve the parishes of the Drung Group. It was built around 1870, to the east of the walled garden of Corravahan.

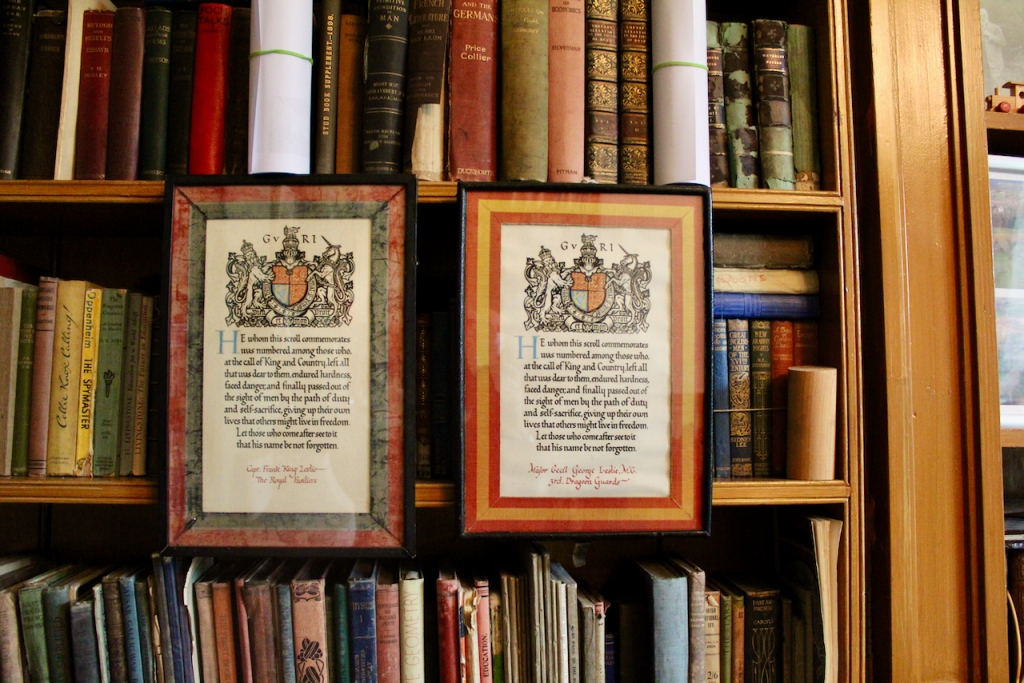

Charles Leslie’s second son, Charles Robert Leslie (1841-1904), lived on the estate, running it for his father after retiring from the British army (the oldest son, John Henry Leslie, married and subsequently lived in England). It was he who became disabled and for whom the elevator was installed. Stephen and I were fascinated to learn that he kept diaries, and that the diaries are on the shelves in the library at Corravahan!

They would be fascinating to read, as he was engaged in Canada as Captain of the 25th King’s Own Borderers, who repelled a Fenian invasion from New York state! The Fenians, an Irish Republican organisation based in the United States, conducted raids on British army forts, custom posts and other targets in Canada in an attempt to pressure the British to withdraw Ireland [4].

Charles never married and when he died, in September 1904, ownership of Corravahan passed to his younger brother, Cecil, third son of Reverend Charles Leslie and Louisa.

The Corravahan website tells us that Cecil Edward St. Lawrence Leslie (1843-1930) was educated at Oxford, returning to live permanently at Corravahan, and served periodically on the judiciary in Cavan, otherwise living off his investments and rental income on lands he owned. The website continues:

“In 1876, he married Emily Louisa Massy-Beresford (1854-1890), a first-cousin-twice-removed of Rt. Rev. Marcus Gervais Beresford, the builder of Corravahan. She was the daughter of Very Rev. John Maunsell Massy, Dean of Kilmore, who had wisely added the name Beresford (by royal licence) subsequent to his equally wise marriage to Emily Sarah Beresford, daughter of Rev. John Isaac Beresford of Macbie Hill, Peebles-shire, who was the grand-niece of George, Bishop of Kilmore and great-great-granddaughter of the Earl of Tyrone. Cecil and “Loo” had two sons, Charles and Cecil George, the last children raised at Corravahan before the present.”

The elder son, Charles, died at the age of 13. The younger, Cecil George, nicknamed “Choppy,” joined the military. He died of tuberculosis in 1919, predeceasing his father.

A fourth son of Reverend Charles and Louisa, Henry King Leslie (1844-1926) married Ruth Hungerford-Eagar. The website tells us that he served as a land agent to numerous estates, and it was while he was living at Kilnahard, Mountnugent, possibly working for the Nugent family of Bobsgrove, or Farren Connell, that Ruth gave birth to their son, Frank King Leslie, in 1885. He died in Gallipoli in 1915. Henry and Ruth also had two daughters, Madge and Joan, to whom we will return presently.

The youngest of Reverend Charles’s five sons, Arthur Trevor Leslie (1847-1886), also joined the military, and died in 1886 at Corravahan, probably due to illness contracted in his service.

By 1930, then, all of Rev. Charles Leslie’s five sons had died, the only survivors of the subsequent generation were Henry’s daughters, Margaret Ruth Leslie (1886-1972) and Nancy Joan Leslie (1888-1972). Thus upon Cecil’s death in 1930 he left Corravahan to his nieces, along with the accumulated wealth of the previous generations. The sisters remained unmarried.

Frank King Leslie’s fiancee, May Haire-Forster, remained close to the family and joined Madge and Joan to live in Corravahan after 1930. The three women lived together in the house for forty years. They modernised the house, having inherited quite a bit of money from their brothers, so they were able to install electricity and central heating. They were careful to preserve many elements of the house that they may have remembered fondly as children, however, in a way that someone who did not grow up in the house may not have retained. They were popular in the neighbourhood and continued to give employment to people of the area.

The sisters installed electric lights before rural electrification of Ireland, which occurred in 1957. The sisters innovatively used a wind turbine system to create their electricity.

The house passed in 1972 to Madge’s god-daughter, Elizabeth Lucas-Clements, daughter of the Lucas-Clements family of nearby Rathkenny House. Rathkenny, also designed by William Farrell, was built for Theophilus Lucas-Clements in the 1820s [5]. Having sold Corravahan and its contents in 1974, largely to meet various bills for death-duties, Elizabeth Lucas-Clements retained much material that was personal to the Leslie family, and, among other items, gave the diaries of Charles Robert Leslie to the current owner.

The house then stood empty for five years and was occupied only occasionally for a further twenty-five years, until it was purchased by its current owners, the Elliotts. The surrounding farmland and outbuildings, walled garden and orchard no longer belong to the house. The National Inventory tells us: “The walled garden is located to the south-east of the lawns, and once formed part of an extensive landscape of gardens, woods, paths, and ponds more in the style of a country house demesne reflecting the particularly wealthy status of the clergy incumbents of Beresford and following him Rev. Charles Leslie.” The Elliotts are restoring the eight acres they have remaining around the house.

We moved from the former morning room to the drawing room.

The room has an egg and dart pattern ceiling cornice and a large bay window. This is the “glazed tripartite loggia having steps to the garden” mentioned in the National Inventory [see 1. And we saw a loggia before in the Old Rectory in Killedmond, County Carlow]. It does not look like a door, but the middle panel of the windows slides up into the frame in an ingenious manner to make a door. Ian is not sure if this bay window is original to the house. On the one hand, it is not well-constructed as it does not have a relieving arch over it, which would lend solidity, and as a result, the ceiling has cracked over time. This seems particularly odd as there is a relieving arch over another window. But William Farrell has built similar designs in other places. Ian has seem something similar to the door/window in Castle Ward, County Down, and apparently there is something like it in Abbeville in Dublin, another Beresford residence.

On a purely personal note, the ironwork on the windows reminded me of the protecting grille on our windows and doors in Grenada, though the Grenada one is simpler.

I admired the built-in shelving unit in the drawing room and asked whether it was original to the house.

It was not. There were doors here between the drawing room and the former morning room, closed up when the second library was created. You can see Stephen wearing his mask in the photograph, as we were all protecting ourselves from Covid-19!

We entered the dining room next. Ian pointed out that as we followed the typical daily progress of a house resident from room to room: morning room to drawing room to dining room, we followed the path of the sun shining in to the house! It was well designed!

The bow in the house contains the dining room.

The bow makes the room look grander and larger than it would with straight walls. It necessitates having slightly curved wooden window frame joinery, however, requiring skill and extra expense. The glass in the windows, fortunately, is not curved, as that would be even more expensive and difficult. The room has more beautiful curtain pelmets and decorative plaster coving.

It also has a decorative ceiling rose. The other architectural novelty in this room is an arched recess for a sideboard.

Interestingly, it appears that the Beresfords had a smaller sideboard than the Leslies. The Leslies had to have the recess widened! They did not leave their sideboard but the Elliotts were lucky enough to find one that fit perfectly!

The room has the Classical feature of symmetrical details, which includes the doors. There are four doors in the room. Two of them, however, exist merely for balance. One leads to a drinks cabinet and the other appears to have been used as a cupboard for the silverware, as it has a strong lock. The other doors lead from the main house, and to the servants’ area, for serving the food.

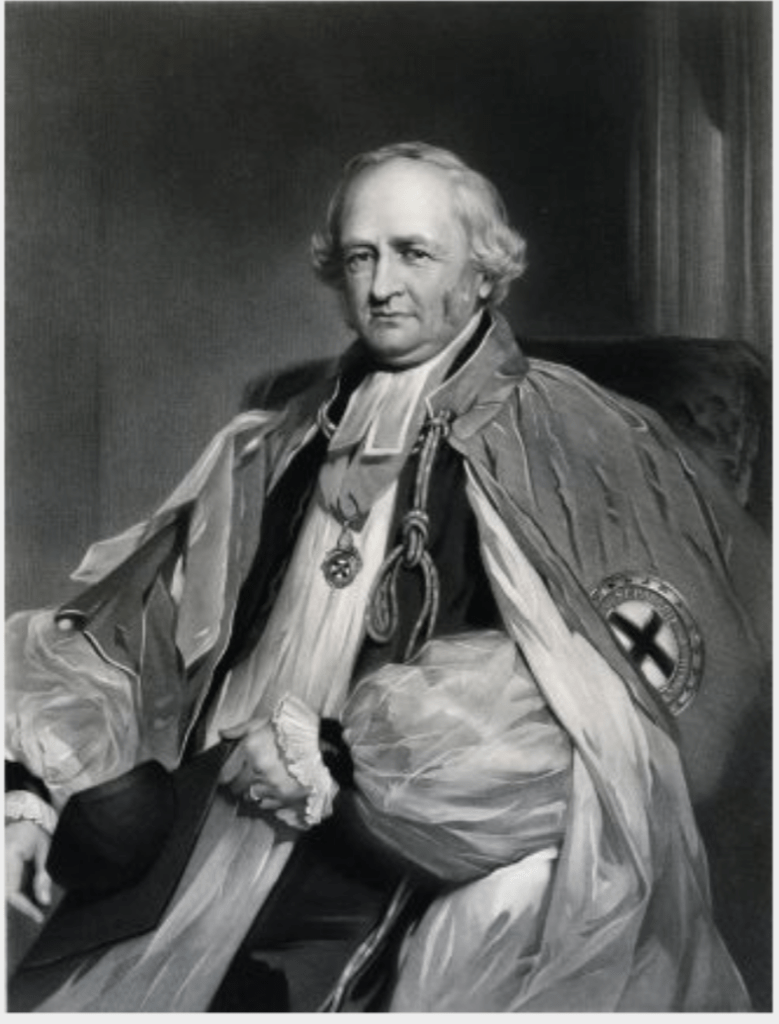

I was also delighted to see the old fashioned railing around the top of the walls – a tapestry rail. It is perfect for hanging pictures. In the room there was a picture of Marcus Gervais Beresford, who later became the Archbishop of Armagh, and one of Bishop John Leslie, the father of Charles who moved into the house when Marcus Beresford left.

The tapestry rail runs all around the room along the ceiling. On the right, above, is Marcus Gervais Beresford. Note that on the top of the portrait frame is the mitre of an Archbishop. The portrait of Bishop John Leslie is on the left hand side, and in the photograph below:

Next, we went out to the servants’ hall. It has large built-in cupboard along the wall:

This was specially built to hold extra leaves of the dining room table! I wondered what was the purpose of the little shelf under the cupboard. Ian explained – the board on the wall across from the ledge comes down to form a shelf, on which the dishes coming from the kitchen were placed. There is another shelf that can be lowered behind where I was standing to take the photograph, that is on the other side of the door coming from the dining room, which would have been for the dirty dishes!

Before the cupboard was built for the leaves of the table, the wall had what looked like wooden panelling. Guests would have seen this if they glimpsed out into the hall from the dining table, and they would have been impressed to see that even the serving hall was panelled.

What looks like carved wood panelling, is actually wallpaper! I couldn’t believe it – the wood looks so real! I had to run my finger over it, and still found it hard to believe! Unfortunately the rest of the wallpaper has been painted over, below the leaf cupboard. The wood appearance wallpaper would have come halfway up the wall to look like wood panelling.

From the hall we entered a kitchen which is inside the timber lean-to. This was added on since the original kitchen was in the basement. A dumbwaiter was built into this lean-to for the sisters Madge and Joan, for the ease of their housemaid.

Inside the shaft where the dumb waiter goes up and down, Ian pointed out the original wall of the house. It was here that we could see the way the wall had been drawn on, “ruled and lined rendered walls,” to make it look like it was made of stone.

The servants would have lived in the basement and in the outbuildings to the side of the house in the coachyard and stable block. The top of the house was the nursery. I took a photo of the outbuildings from the top floor of the house, the attic storey.

You can just about see the solar panels which have been carefully installed, in such a way as not to damage the roof slates, which have been repaired and replaced by the current owners. The building on the left is new, but has been so well-made that it looks like the older buildings! Here again Ian pointed out how the render has been decorated so that around the new arches, it looks like stonework but is really cement plaster, carefully etched to mimic the original cut stone of the adjacent coach-house doorways.

There are two staircases in the house – the back stairs for the servants, and the main staircase.

The back stairs lead up to the nursery attic storey.

The rooms upstairs are airy and bright and surprisingly large. Looking out a window, we had a bird’s eye view of the giant old Lebanon Cedar tree, which must be about 300 years old.

My family had a Lebanese cedar also nearly as old, at our house in Puckane, County Tipperary:

We then used the main staircase to return downstairs. It has a mahogany handrail and carved timber balusters, and is overlooked by a grand arched window.

This Wyatt window topped with arches is a style favoured by the architect William Farrell. There are similar windows in other houses he built, Rathkenny House and the See House in Kilmore. There is also a window like this in the courthouse in Virginia, County Cavan, but this is not an original – the window was originally an arch and was copied from Farrell’s windows.

The stairs are ornamented with Vitruvian scrolls, which is a motif from Greek temples. The fact that these were carved in stone in temples lends to the idea that the stairs are made of stone, although they are of wood. The bannisters are painted black and can be mistaken at a glance for wrought iron.

We ended our tour at the bottom of the stairs in another lovely hall space complete with fireplace. We signed the guest book, and look forward to returning to see the garden and to explore more outside!

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Beresford_(bishop)

And

http://www.thepeerage.com/p2601.htm#i26005

[3] http://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Corravahan

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenian_raids

[5] https://www.facebook.com/stephenstown66/posts/2211132052539058?tn=K-R

“At this stage the house passed to Elizabeth Lucas-Clements ( Margaret’s god daughter) of the aforementioned neighbouring Rathkenny. Catherine Beresford, daughter of the Rt. Hon John de la Poer Beresford had, years before, married Henry Theophilus Clements of also nearby Ashfield Lodge, a cousin of the Rathkenny Lucas-Clements.”

The blog gives a great image of the way the gentry families intermarried and connected:

“These houses and families can often be like circles looping into each other, not unlike Olympic rings, connecting at a point, distant again perhaps for a period, but uniting again before this “pattern “ frequently continues unabated.”

5 thoughts on “Corravahan House and Gardens, Drung, County Cavan H12 D860”