Open dates in 2024: May 2-Sept 7, Thurs, Fri, Sat, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP €5, student €3

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

Riverstown is famous for its stucco work. It contains important plasterwork with high-relief figurative stucco in panels on the ceiling and walls of the dining room, by Paolo and Filipo Lafranchini. The brothers also worked in Carton House in County Kildare (see my entry for places to stay in County Kildare https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/04/27/places-to-visit-and-to-stay-leinster-kildare-kilkenny-laois/) and in Kilshannig in County Cork (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/12/10/kilshannig-house-rathcormac-county-cork/).

The Swiss-Italian stuccadores were brought to Ireland from England in 1738 by Robert Fitzgerald (1675-1744) 19th Earl of Kildare, who built both Leinster House in Dublin (first known as Kildare House until his son was raised to be Earl of Leinster) and Carton House.

Going back to its origins, the estate of Riverstown was purchased by Edward Browne (b. 1676), Mayor of Cork. He married Judith, the heiress daughter of Warham Jemmett (b. 1637), who lived in County Cork. The present house possibly dates from the mid 1730s, Frank Keohane tells us in Buildings of Ireland: Cork City and County. [2] A hopper with the date 1753 probably records alterations, when the gable end at one side was replaced by full-height canted bays.

Mark Bence-Jones describes Riverstown in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

“…The house consists of a double gable-ended block of two storeys over a basement which is concealed on the entrance front, but which forms an extra storey on the garden front, where the ground falls away steeply; and a three-storey one bay tower-like addition at one end, which has two bows on its side elevation. The main block has a four bay entrance front, with a doorway flanked by narrow windows not centrally placed.” [3]

The tower-like third storey on part of the house was possibly added by architect Henry Hill around 1830, Keohane tells us. Henry Hill was an architect who worked in Cork, perhaps initially with George Richard Pain, and later with William Henry Hill and Arthur Hill.

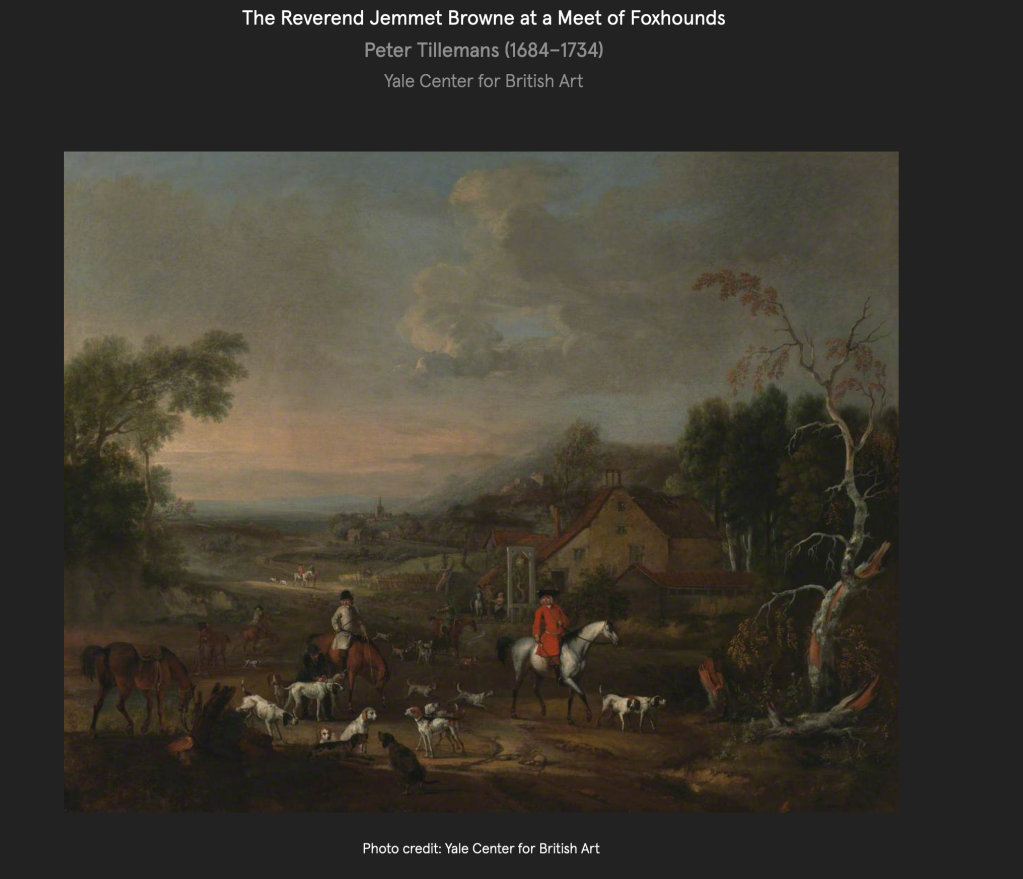

As Riverstown and its plasterwork was described in 1750 in Smith’s History of County Cork, it must have been created before this, perhaps when Browne’s son Jemmet Browne was elevated to the position of Bishop of Cork in 1745. He later became Archbishop of Tuam.

Reverend Jemmett Browne gave rise to a long line of clerics. He married Alice Waterhouse, daughter of Reverend Thomas Waterhouse. His son Edward (1726-1777) became Archbishop of Cork and Ross, and a younger son, Thomas, also joined the clergy.

Edward Archbishop of Cork and Ross named his heir Jemmett (1753-1797) and he also joined the clergy. He married Frances Blennerhassett of Ballyseede, County Kerry (now a hotel and also a section 482 property, see my entry). If the tower part of the house was built in 1830 it would have been for this Jemmett Browne’s heir, another Jemmett (1787-1850).

In Beauties of Ireland (vol. 2, p. 375, published 1826), James Norris Brewer writes that: “the river of Glanmire runs through the gardens banked with serpentine canals which are well stocked with carp, tench, etc. A pleasant park stocked with deer, comes close to the garden walls. The grounds of this very respectable seat about in aged timber and the whole demesne wears an air of dignified seclusion.”

The first Jemmett Browne was friendly with Laurence Sterne, author of Tristram Shandy. The bawdiness of the novel demonstrates that clerics at the time led a different life than those of today! Jemmett Browne’s interest in fine stucco work was probably influenced by fellow clerics Bishop George Berkeley, Samuel “Premium” Madden and Bishop Robert Clayton. Samuel Madden recommended, in his Reflections and Resolutions Proper to the Gentlemen of Ireland that stucco is substituted for wainscot. [4] Bishop Clayton owned what is now called Iveagh House on St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin (see my entry, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/09/23/open-house-culture-night-and-heritage-week-dublin-visits/ ).

The stucco work is so important that the Office of Public Works feared it would be lost, as the house was standing empty in the 1950s before being purchased by John Dooley, father of the current owner, in around 1965. Under the direction of Raymond McGrath of the Office of Public Words, with advice from Dr. C. P. Curran, the authority on Irish decorative plasterwork, moulds were taken in 1955-6. The moulds are now displayed prominently in the home of Ireland’s President, Áras an Uachtaráin. (see my entry on the Áras in the entry on Office of Public Works properties in Dublin, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/01/21/office-of-public-works-properties-dublin/ )

Shortly after John Dooley purchased the property, the members of the Irish Georgian Society decided to help to restore the plasterwork.

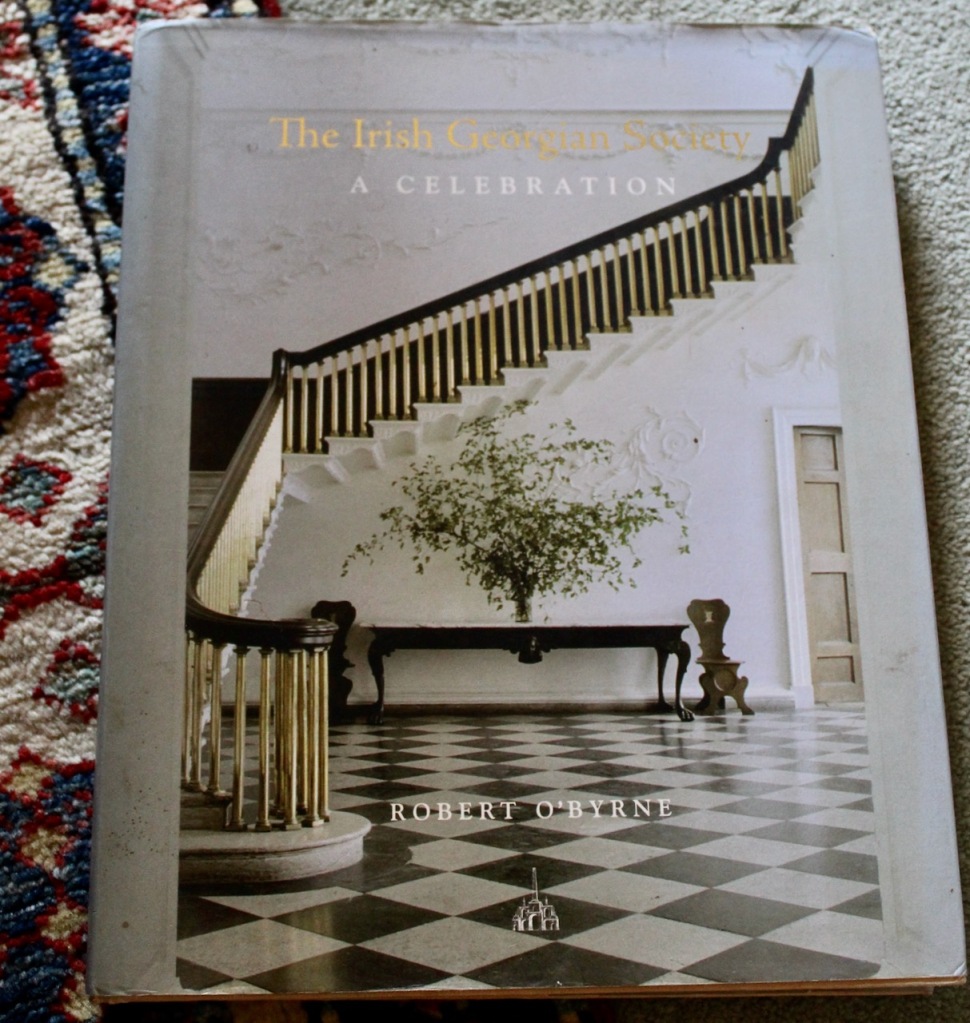

The book published on the 50th anniversary of the Irish Georgian Society has part of a chapter on Riverstown and the Irish Georgian Society’s role in restoration of the Lafranchini plasterwork in the 1960s. By this time, John Dooley had purchased Riverstown, after it has been standing empty. At the time, Dooley had not yet moved in, and the dining room was not preserved to the standard the Georgian Society would have liked. The book has a photograph of potatoes being stored in the dining room.

The entrance hall of Riverstown is also impressive, and the members of the Georgian Society also helped to clean the plasterwork in this room. The walls curve, and the room has an elegant Neoclassical Doric frieze and shapely Corinthian columns.

Mark Bence-Jones decribes: “The hall, though of modest proportions, is made elegant and interesting by columns, a plasterwork frieze and a curved inner wall, in which there is a doorcase giving directly onto an enclosed staircase of good joinery. To the left of the hall, in the three storey addition, are two bow-ended drawing rooms back to back. Straight ahead, in the middle of the garden front, is the dining room, the chief glory of Riverstown.”

The Lafranchini work in the dining room derives from Maffei’s edition of Agostini’s Gemme Antiche Figurate (1707-09). Frank Keohane notes that the Maffei’s engravings were also used for the decoration of the Apollo Room in 85 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, also by the Lafranchini brothers.

The ceiling at Riverstown: winged figure of Father Time, rescuing Truth from the assaults of Discord and Envy, taken from the allegorical painting by Nicholas Poussin which he painted on the ceiling in France for Cardinal Richelieu in 1641 and now hangs in the Louvre, Paris.

C. P. Curran tells us that the history of the Lafranchini brothers is obscure, but they “represent one of the successive waves of stuccodores who from quite early periods swarmed over Europe from fertile hives in the valleys of either side of the Swiss Italian Alps….They worked in some unascertained way side by side with local guildsmen and introduced new motifs and methods. Their repertory of ornament was abundant and they excelled in figure work.” [4] They executed their work in Carton in 1739, Curran tells us, and in 85 St. Stephen’s Green in 1740.

Keohane tells us that the simple eighteenth century black-marble slab chimneypiece was installed in the 1950s when the house was saved by the Dooley family from ruination. It replaced a remarkable overmantel, now in an upper room, with great scrolled jambs garlanded with flowers and tufted with acanthus, and a comic mask in the centre of the frieze which possibly depicts Bishop Browne.

The work by the members of the Irish Georgian Society on the dining room in Riverstown was complete by the end of 1965. John Dooley continued the restoration of the rest of the house, and it is now kept in beautiful condition by his son Denis and wife Rita, with many treasures collected by the Dooleys. A 1970 Irish Georgian Society Bulletin, Robert O’Byrne tells us, reported further improvements made by the Dooleys. It tells us that one of the house’s two late-eighteenth century drawing rooms adjoining the dining room:

“has been given a new dado, architraves, chimney-piece, overdoors and overmantel. These have been collected by John Lenehan of Kanturk, who rescued them from houses in Dublin that were being demolished and inserted them at Riverstown.”

The two drawing rooms do indeed have splendid over mantel and overdoors. The drawing room has been hung with green silk wall covering. The Dooleys have shown fine taste for the decoration and maintenance of the rooms and I suspect John Dooley knew what he was doing when he purchased and thus saved the house.

A fine wooden staircase brings us upstairs to a spacious lobby containing a Ladies’ conversation chair. Keohane suggests the stair may have originally been open to the front hall, but is now hidden by a screen wall. He writes that this arrangement probably dates from c. 1784, when Phineas Bagnell was granted a long lease of the house.

The owners’ bedroom has an extraordinary carved marble mantel. It was probably originally in the room with the Lafranchini stuccowork. It has great scrolled jambs garlanded with flowers and tufted with acanthus, and a comic mask in the centre of the frieze which possibly depicts Bishop Browne, Frank Keohane tells us.

The Dooleys have a garden centre, which is situated behind the house. They maintain the gardens with its rolling lawns beautifully. The Glanmire river passes by the bottom of the garden.

[1] https://repository.dri.ie/catalog

[2] p. 556, Keohane, Frank. Buildings of Ireland: Cork City and County. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2020.

[3] Bence-Jones, Mark A Guide to Irish Country Houses. (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] Curran, C.P. Riverstown House Glanmire, County Cork and the Francini. A leaflet given to us by Denis Dooley.

One thought on “Riverstown House, Riverstown, Glanmire, County Cork T45 HY45”