contact: Ann French

Tel: 087-2245726

www.thechurch.ie

Open: Jan 1-Dec 23, 27-31, 11am-10pm Fee: Free

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

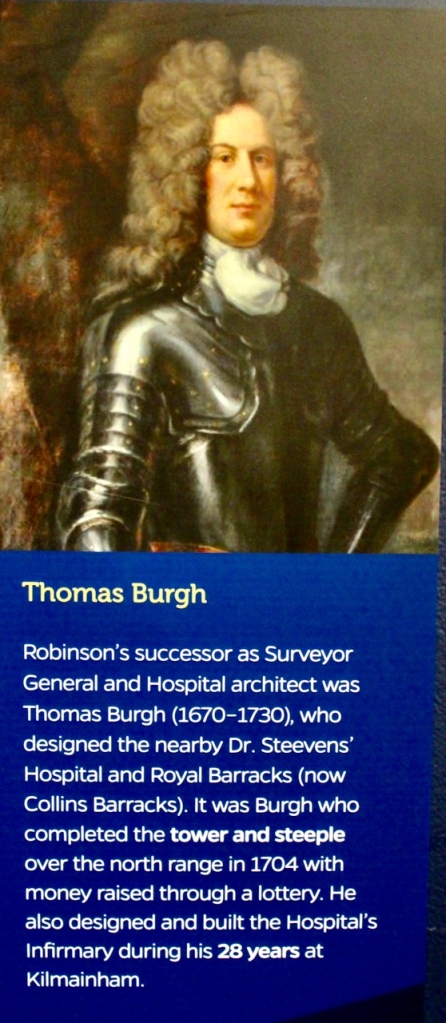

The former St. Mary’s Church of Ireland was built from 1700-1704. It is now in use as bar and restaurant, with modern glazed stair tower built to northeast, linked with an elevated glazed walkway to the restaurant at the upper level within the church. The National Inventory tells us that it was designed by William Robinson and completed by his successor, Thomas Burgh.

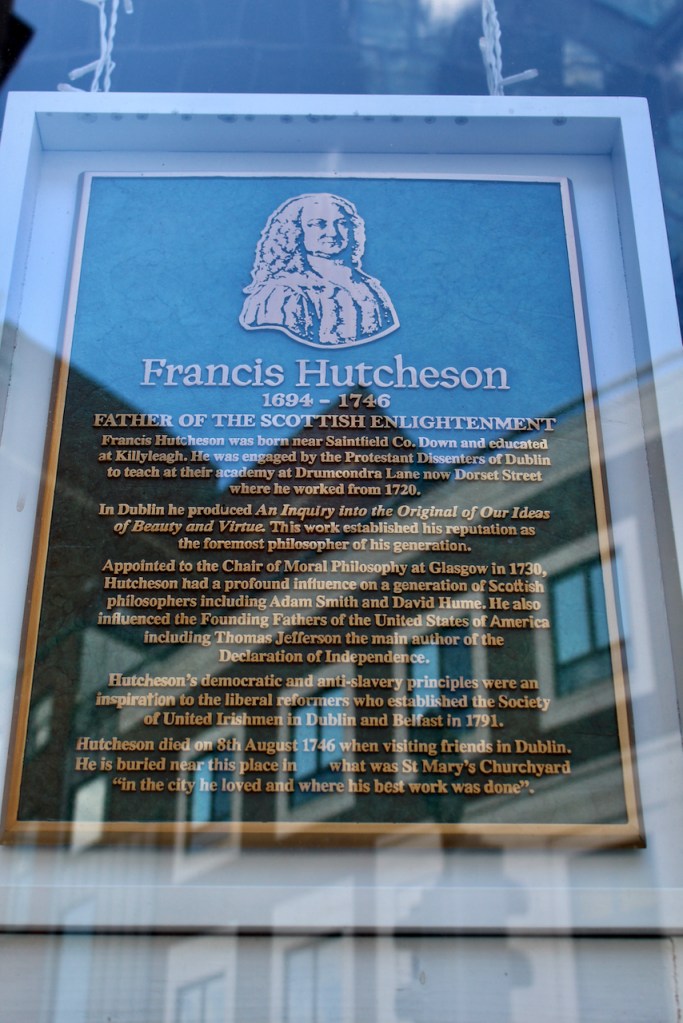

The church has a special place in my husband’s heart because his ancestor John Winder visited Dublin to preach a sermon here in around 1720, when he was rector at Kilroot in County Antrim, a position he obtained after Jonathan Swift. St. Mary’s parish was founded in 1697, the second parish on the north side of the River Liffey (the first must have been St. Michans). It took its name from the medieval monastery of St. Mary’s Abbey that had occupied most of the north side of the river from 1139 until its dissolution in 1539.

It was closed as a church in 1986 due to the fall of parishioners, as residents moved from the city centre. The building was used for various purposes until purchased by publican John Keating in 1997. Until it was changed for use as a bar it contained the oldest unaltered church interior in Dublin, and much of this has been preserved.

William Robinson was made surveyor general of buildings in Ireland in 1671. He was also engineer general and master of ordinance, so was responsible for fortifications. He built Charles Fort in Kinsale, and in 1677–8 he was adviser and contractor on the construction of Essex Bridge in Dublin. In 1679 was involved in the rebuilding of Lismore cathedral, Co. Waterford, and designed the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham (1680–84). [1] In 1682 he oversaw the construction of Ormond Bridge in Dublin.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that William Robinson’s patent as surveyor general was renewed in 1684, though he now shared the post with William Molyneux (1656–98), who later oversaw the partial construction of Robinson’s design for the courtyard of Dublin castle when he and Robinson were deprived of the surveryorship by the lord deputy, the earl of Tyrconnell. Robinson went to England during Tyrconnell’s deputyship and Molyneux remained in Ireland and carried out extensive building work at Dublin castle, presumably to Robinson’s designs.

In 1689 Robinson was appointed comptroller general of provisions and commissary general of pay and provisions in the Williamite army, the latter position being shared with Bartholomew van Homrigh (the father of Jonathan Swift’s friend, whom he called “Vanessa”).

Robinson returned to Ireland, and was Elected MP for Knocktopher, Co. Kilkenny (1692–3) and Wicklow town (1695–9) and in 1702 was appointed to the Privy Council in Ireland. In 1695 he rebuilt Dublin’s Four Courts, and in 1703–4 he designed Marsh’s Library in Dublin, his last major work.

Robinson served as MP for Dublin University 1703–12, and he purchased forfeited lands in Carlow and Louth in April and June 1703. His career ended in disgrace however as he was accused of shady financial dealings and misrepresenting public accounts for which he was responsible. (see [1])

Thomas Burgh (1670–1730) succeeded Molyneux and Robinson in 1700 as surveyor-general, and was also made lieutenant of the ordnance in Ireland. The rebuilding of Dublin castle, started by Robinson, advanced considerably under Burgh, but his undisputed masterpiece was to be TCD library. His work designing and building the lower part of the library began in 1712 and continued into the next decade. It was finally opened in 1732. He may have been responsible for designing Kildrought house in Celbridge, Kildare (see my entry). He too had engineering interests including navigation and coalmining. He lived in Oldtown, County Kildare, and became high sheriff of the county in 1712 and was MP for Naas 1713–30. [2]

It is difficult to photograph the church, as it is in the middle of city streets, and Christine Casey writes in her The Buildings of Ireland: Dublin (2005) that it exhibits “a curious amalgam of awkwardness and aplomb”! [3]

St. Mary’s church has four-bay double-height side elevations, with convex quadrant single-bay links to a shallow chancel which contains a lovely chancel window. It has a three-stage tower at the opposite end flanked by lower two-storey vestibules. It does not have a spire.

The west front has the main entrance door (no longer in use as the main door, which is on the north facade). Unfortunately I was unable to take a good photograph due to the position of outdoor tables and sheltering umbrellas. The doorcase is of Portland stone with Ionic columns and an entablature. Casey tells us that the lugged surrounds of the outer vestibule door are of brown sandstone.

The window frame on the east end chancel is of Portland stone, which Casey tells us “has a vigour and plasticity rare in a city by-passed by the Baroque.” She describes the window:

“Above a raised granite plinth, two broad panelled pilasters support an emphatic curved scroll-topped hood-moulding with urns to centre and ends, while successive inner lugged framed have scrolled base terminals.”

Casey suggests that the gable on this end may be a later addition.

William Robinson prepared a model for this window, and may have designed the unusual plan for the church. It was completed by Thomas Burgh in 1704 and in 1863, S. Symes may have inserted new windows as well as replacing the perimeter wall with railings. The original chancel window of St. Mary’s was smashed by vandals on the result of polling at the election in 1852. The current window was set in 1910, commissioned in 1909 by John North, the proprietor of the “Hammam,” a Turkish Bath on O’Connell (then called Sackville) Street. The new window reads: “To the glory of God and in affectionate memory of his daughters Maria North (Molly) and Rosanna (Rose) wife of Joseph Armstrong also his grandchild John Hubert Armstrong (Jack) erected by John North 1909.”

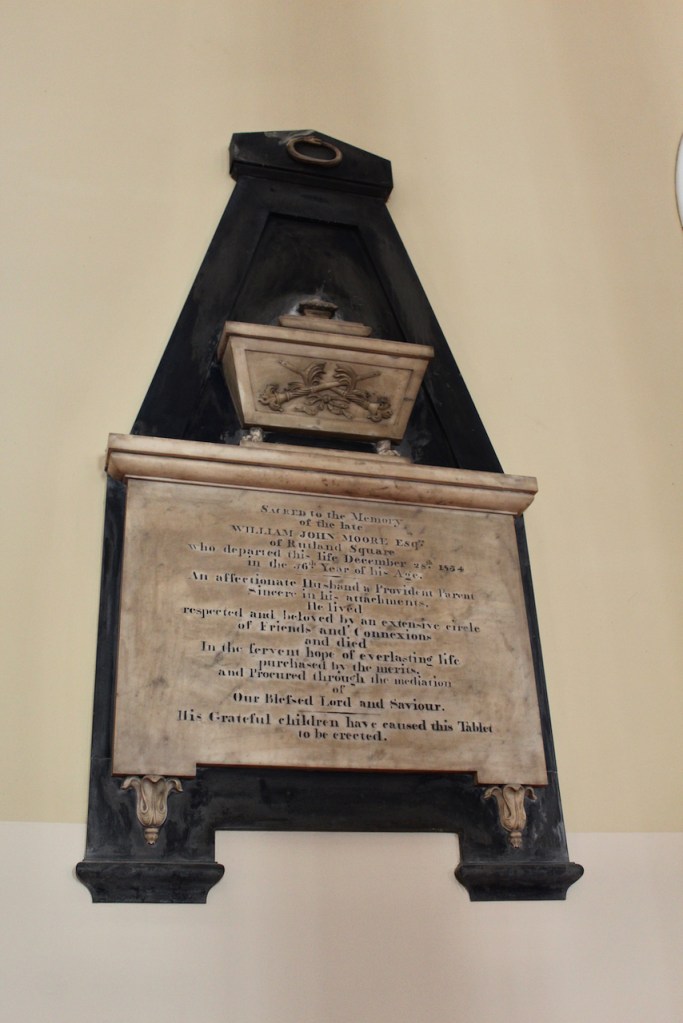

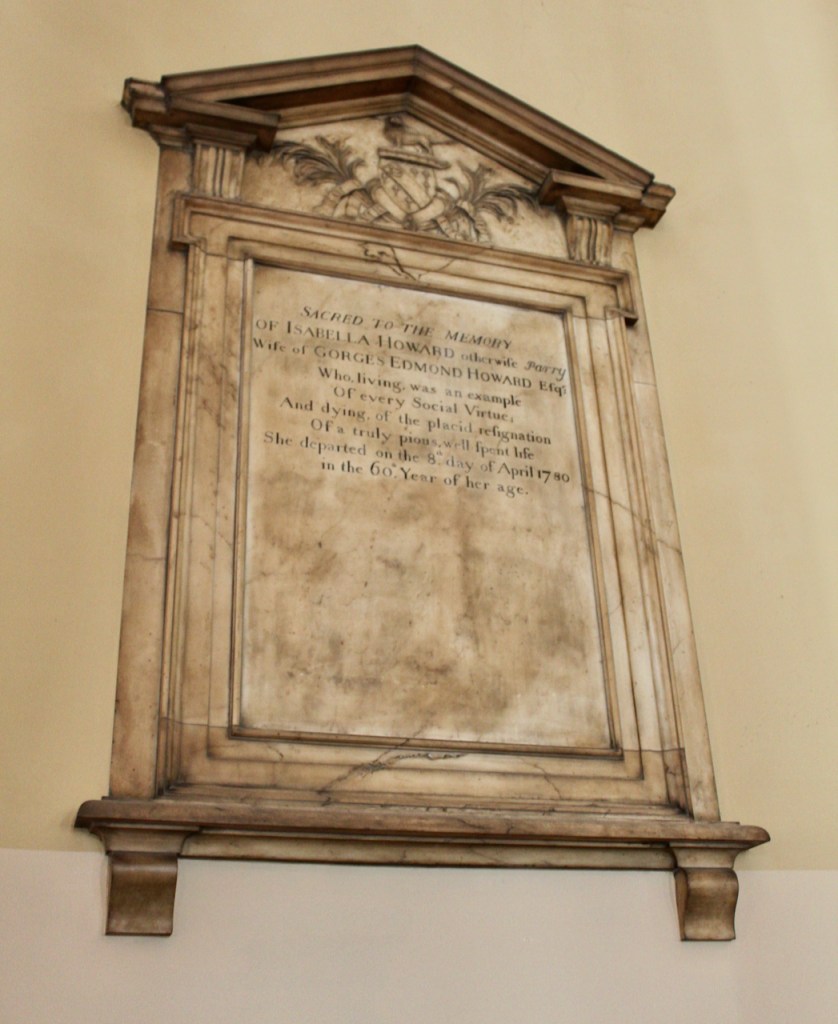

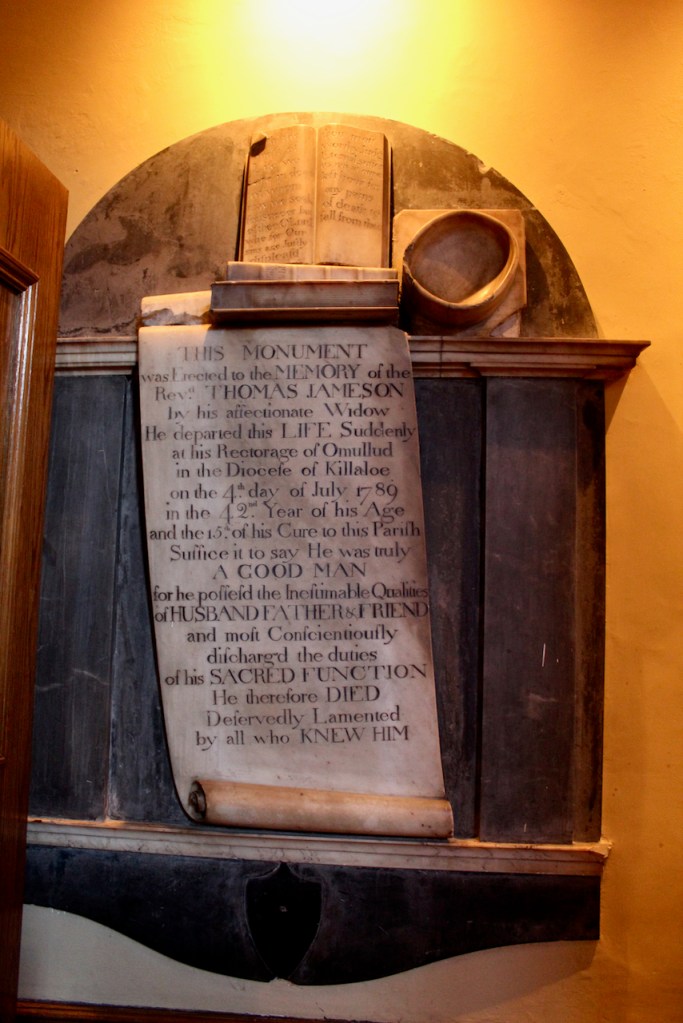

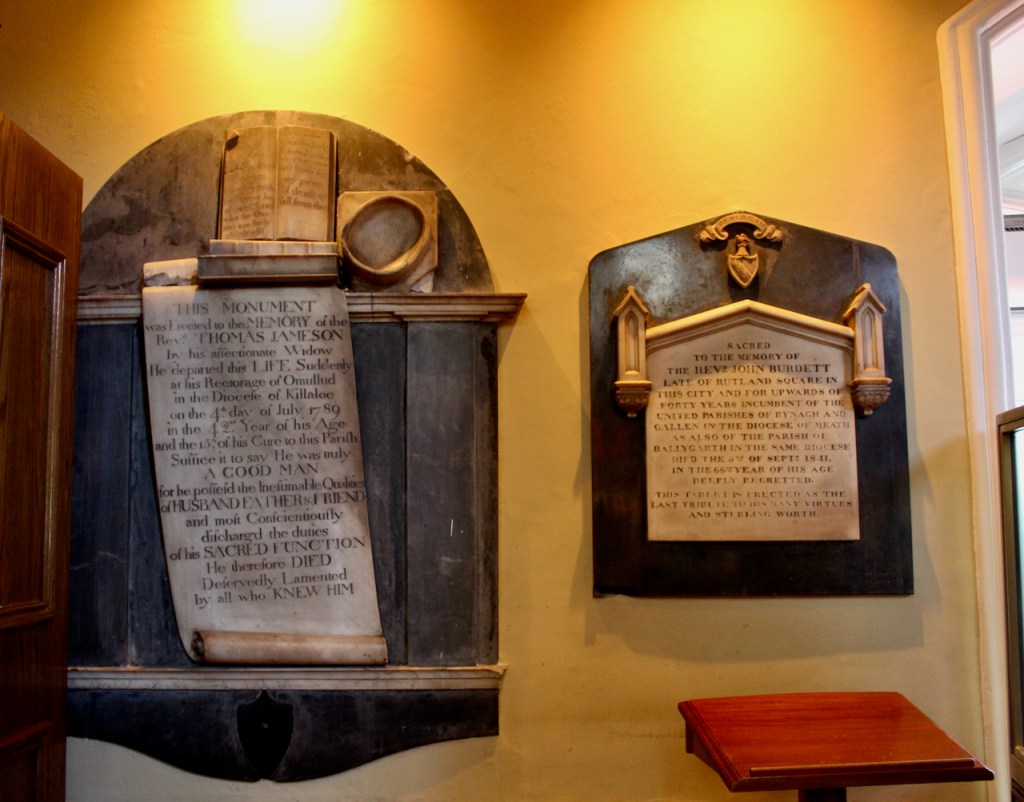

Inside, it is of double height with a gallery surrounding three sides. On the fourth side is the east window. The west end has a large organ on the upper floor. The centre of the floor is taken up with an oval shaped bar which is made attractive by its arrangement of bottles and glasses. The gallery is carried on octagonal timber-clad limestone shafts. Above, the gallery reaches up to the ceiling with fluted square Ionic columns. The ceiling is barrel-vaulted. Memorial monuments still line the walls. Outside, the gravestones have been moved to one end of the public square.

The east Chancel window has a lugged and scrolled surround.

Casey tells us that the building was remodelled in 2002-5 as a bar and restaurant by Duffy Mitchell Donoghue, who filled in the crypt and altered the floor level of the nave. The glazed tower holds a cylindrical elevator.

In 1761 Arthur Guinness (1725-1803), founder of the Brewery, married Olivia Whitmore in the church. His son, also named Arthur, married here also.

The National Inventory tells us: “It was the first classical parish church in the city and was the site of Arthur Guinness’s marriage in 1761. Wolfe Tone was baptized here and the church also witnessed John Wesley’s first Irish sermon... The galleried interior is one of the earliest in Dublin, and is a triumph of Classical timber design. Grand proportions combine with the set-pieces of the original organ case, east window and surviving Corinthian reredos, connected by an ornate mix of joinery and innovative modern alterations, to create a sumptuous and exuberant space. Mary Street was laid out by Humphrey Jervis from the mid-1690s and in 1697 the parish of Saint Michan’s was divided into three which precipitated the construction of Saint Mary’s. Jervis Street was named for the developer himself and was once home to seventeenth and eighteenth-century buildings. The streets are much altered now and consist largely of Victorian buildings, leaving Saint Mary’s to ground the district in its earlier historic milieu. As such, it makes a highly significant contribution to the streetscape and to Dublin’s overall architectural fabric.”

A rather simple baptismal font in the church is the font in which Theobald Wolfe Tone was baptised, and also Sean O’Casey the playwright.

The organ was designed by Renatus Harris. George Frederick Handel, who wrote the famous “Messiah,” lived nearby on Abbey Street and was a regular visitor to Mary’s to play on this organ.

The organ case, Casey tells us, includes the bases of three pipe-clusters with cherubim and scrolls.

The vestibules have early eighteenth century staircases.

Below ground, is the Cellar Bar. These function rooms are located in an area that was excavated out from underneath the church, and are not part of the original building. There are six crypts in the basement of the church, and 32 skeletons were removed and reinterred elsewhere when the church was converted to its current use. Access to the crypt was by an external stairwell in the church.

Outside there is a public square, Wolfe Tone Park, and grave slabs are stacked up at one end of this park.

[1] Dictionary of Irish Biography for Sir William Robinson, https://www.dib.ie/biography/robinson-sir-william-a7736

[2] https://www.dib.ie/biography/burgh-thomas-a1135

[3] p. 89-91. Casey, Christine. Buildings of Ireland: Dublin, The City within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2005.

4 thoughts on “The Church, Junction of Mary’s Street/Jervis Street, Dublin”