On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

Munster’s counties are Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford.

For places to stay, I have made a rough estimate of prices at time of publication:

€ = up to approximately €150 per night for two people sharing (in yellow on map);

€€ – up to approx €250 per night for two;

€€€ – over €250 per night for two.

For a full listing of accommodation in big houses in Ireland, see my accommodation page: https://irishhistorichouses.com/accommodation/

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

Waterford:

1. Ballysaggartmore Towers, County Waterford

2. Bishop’s Palace Museum, Waterford

3. Cappagh House (Old and New), Cappagh, Dungarvan, Co Waterford – section 482

4. Cappoquin House & Gardens, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford – section 482

5. Curraghmore House, Portlaw, Co. Waterford – section 482

6. Dromana House, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford – section 482

7. Dungarvan Castle, Waterford – OPW

8. Fairbrook House, Garden and Museum, County Waterford

9. Lismore Castle Gardens

10. Mount Congreve Gardens, County Waterford

11. The Presentation Convent, Waterford Healthpark, Slievekeel Road, Waterford – section 482

12. Reginald’s Tower, County Waterford – OPW

13. Tourin House & Gardens, Tourin, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford – section 482

Places to stay, County Waterford

1. Annestown House, County Waterford – B&B €

2. Ballyrafter House, Lismore, Co Waterford

3. Cappoquin House holiday cottages, County Waterford

4. Dromana, Co Waterford – 482, holiday cottages €

5. Faithlegg House, Waterford, Co Waterford – hotel €€

6. Fort William, County Waterford, holiday cottages

7. Gaultier Lodge, Woodstown, Co Waterford €€

8. Richmond House, Cappoquin, Co Waterford – guest house

9. Salterbridge Gate Lodge, County Waterford €

10. Waterford Castle, The Island, Co Waterford €€

11. Woodhouse, County Waterford.

Whole House Rental County Waterford

1. Glenbeg House, Jacobean manor home, Glencairn, County Waterford P51 H5W0 €€€ for two, € for 7-16 – whole house rental

2. Lismore Castle, whole house rental

Waterford:

1. Ballysaggartmore Towers, County Waterford

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988): p. 27. “(Keily, sub Ussher/IFR, Anson, sub Lichfield, E/PB) A late-Georgian house built round a courtyard, on the side of a steep hill overlooking the River Blackwater, to which a new front was subsequently added… A seat of the Keily family. Arthur Keily [1777-1862], who assumed the name of Ussher 1843, built two remarkable Gothic follies in the demesne, to the design of his gardener, J. Smith; one of them a turreted gateway, the other a castellated bridge over a stream. The house was bought at the beginning of the present century by Hon Claud Anson, who sold it 1930s. It was subsequently demolished. The follies remain, one of them being now occupied as a house.” [2]

The National Inventory describes this bridge and its towers:

“Three-arch rock-faced sandstone ashlar Gothic-style road bridge over ravine, c.1845, on a curved plan. Rock-faced sandstone ashlar walls with buttresses to piers, trefoil-headed recessed niches to flanking abutments, cut-stone stringcourse on corbels, and battlemented parapets having cut-stone coping. Three pointed arches with rock-faced sandstone ashlar voussoirs, and squared sandstone soffits. Sited in grounds shared with Ballysaggartmore House spanning ravine with grass banks to ravine…Detached five-bay single- and two-storey lodge, c.1845, to south-west comprising single-bay single-storey central block with pointed segmental-headed carriageway, single-bay single-stage turret over on a circular plan, single-bay single-storey recessed lower flanking bays, single-bay single-storey advanced end bay to right, single-bay single-storey advanced higher end bay to left, and pair of single-bay two-storey engaged towers to rear (north-east) on square plans….Rock-faced sandstone ashlar walls with cut-sandstone dressings including stepped buttresses, battlemented parapets on corbelled stringcourses having cut-stone coping, and corner pinnacles to central block on circular plans having battlemented coping. Pointed-arch window openings with paired pointed-arch lights over, no sills, and chamfered reveals. Some square-headed window openings with no sills, chamfered reveals, and hood mouldings over. Square-headed door openings with hood mouldings over….Detached five-bay single- and two-storey lodge, c.1845, to north-east comprising single-bay two-storey central block with pointed segmental-headed carriageway, single-bay single-storey flanking recessed bays, single-bay two-storey advanced end bay tower to right on a square plan, single-bay two-stage advanced higher end tower to left on a circular plan, and pair of single-bay two-stage engaged towers to rear (south-west) elevation on circular plans…Although initial indications suggest that the lodges are identical, individualistic features distinguish each piece, and contribute significantly to the architectural design quality of the composition. Well maintained, the composition retains its original form and massing, although many of the fittings have been lost as a result of dismantling works in the mid twentieth century. The construction in rock-faced sandstone produces an attractive textured visual effect, and attests to high quality stone masonry.”

The National Inventory describes the gateway: “Gateway, c.1845, comprising ogee-headed opening, limestone ashlar polygonal flanking piers, and pair of attached two-bay single- and two-storey flanking gate lodges diagonally-disposed to east and to west comprising single-bay single-storey linking bays with single-bay two-storey outer bays having single-bay three-stage engaged corner turrets on circular plans…Limestone ashlar polygonal piers to gateway with moulded stringcourses having battlemented coping over, and sproketed finial to apex to opening with finial. Sandstone ashlar walls to gate lodges with cut-limestone dressings including stepped buttresses, stringcourses to first floor, moulded course to first stage to turrets, and battlemented parapets on consoled stringcourses (on profiled tables to turrets) having cut-limestone coping. Ogee-headed opening to gateway with decorative cast-iron double gates. Paired square-headed window openings to gate lodges with no sills, chamfered reveals, and hood mouldings over. Square-headed door openings with chamfered reveals, and hood mouldings over. Pointed-arch door openings to turrets with inscribed surrounds. Trefoil-headed flanking window openings with raised surrounds, and quatrefoil openings over. Cross apertures to top stages to turrets with raised surrounds. All fittings now gone. Interiors now dismantled with internal walls and floors removed.

“An impressive structure in a fantastical Gothic style, successfully combining a gateway and flanking gate lodges in a wholly-integrated composition. Now disused, with most of the external and internal fittings removed, the gateway nevertheless retains most of its original form and massing. The construction of the gateway attests to high quality stone masonry and craftsmanship, particularly to the fine detailing, which enhances the architectural and design quality of the site. The gateway forms an integral component of the Ballysaggartmore House estate and, set in slightly overgrown grounds, forms an appealing feature of Romantic quality in the landscape.“

2. Bishop’s Palace Museum, Waterford

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

p. 282. “The Palace of the (C of I) Bishops of Waterford; one of the largest and – externally – finest episcopal residences in Ireland. Begun 1741 by Bishop Charles Este to the design of Richard Castle. The garden front, which faces over the mall and new forms a magnificent architectural group with the tower and spire of later C18 Cathedral, by John Roberts, is of three storeys; the ground floor being treated as a basement and rusticated. The centre of the ground floor breaks forward with three arches, forming the base of the pedimented Doric centrepiece of the storey above, which incorporates three windows. In the centre of the top storey is a circular niche, flanked by two windows. On either side of the centre are three bays. Bishop Este died 1745 before the Palace was finished, which probably explains why the interior is rather disappointing. The Palace ceased to be the episcopal residence early in the present century, and from then until ca 1965 it was occupied by Bishop Foy school. It has since been sold.”

Archiseek adds: “It has now been extensively restored to showcase artefacts and art from Waterford’s Georgian and Victorian past. The two main facades are quite different: one having seven bays – the central bay having an more elaborate window treatment and a Gibbsian doorway; the other facade has eight bay with a more elaborate entrance and shallow pediment with blank niches.” [3]

The National Inventory explains about the designs of Richard Castle and John Roberts:

“An imposing Classical-style building commissioned by Bishop Miles (d. 1740) and subsequently by Bishop Charles Este (n. d.), and believed to have been initiated to plans prepared by Richard Castle (c.1690 – 1751), and completed to the designs prepared by John Roberts (1712 – 1796). The building is of great importance for its original intended use as a bishop’s palace, and for its subsequent use as a school. The construction of the building in limestone ashlar reveals high quality stone masonry, and this is particularly evident in the carved detailing, which has retained its intricacy. Well-maintained, the building presents an early aspect while replacement fittings have been installed in keeping with the original integrity of the design. The interior also incorporates important early or original schemes, including decorative plasterwork of artistic merit. Set on an elevated site, the building forms an attractive and commanding feature fronting on to The Mall (to south-east) and on to Cathedral Square (to north-west).”

3. Cappagh House (Old and New), Cappagh, Dungarvan, Co Waterford X35 RH51 – section 482

www.cappaghhouse.ie

Open dates in 2024: April, June, Aug, Wed & Thurs, May & Sept, Wed, Thurs & Sat, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 9.30am-1.30pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student/€5, child under 12 free

We visited during Heritage week 2023 – see my writeup https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/12/09/cappagh-house-old-and-new-dungarvan-co-waterford/

and [4]

4. Cappoquin House & Gardens, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford P51 D324 – section 482

see my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/01/24/cappoquin-house-gardens-cappoquin-co-waterford/

www.cappoquinhouseandgardens.com

Open dates in 2024: Apr 8-13, 15-20, 22-27, May 1-4, 6-18, 20-25, Aug 12-31, 9am-1pm Gardens open all year, except Sundays, 9am-4pm

Fee: house/garden €15, house only €10, garden only €6

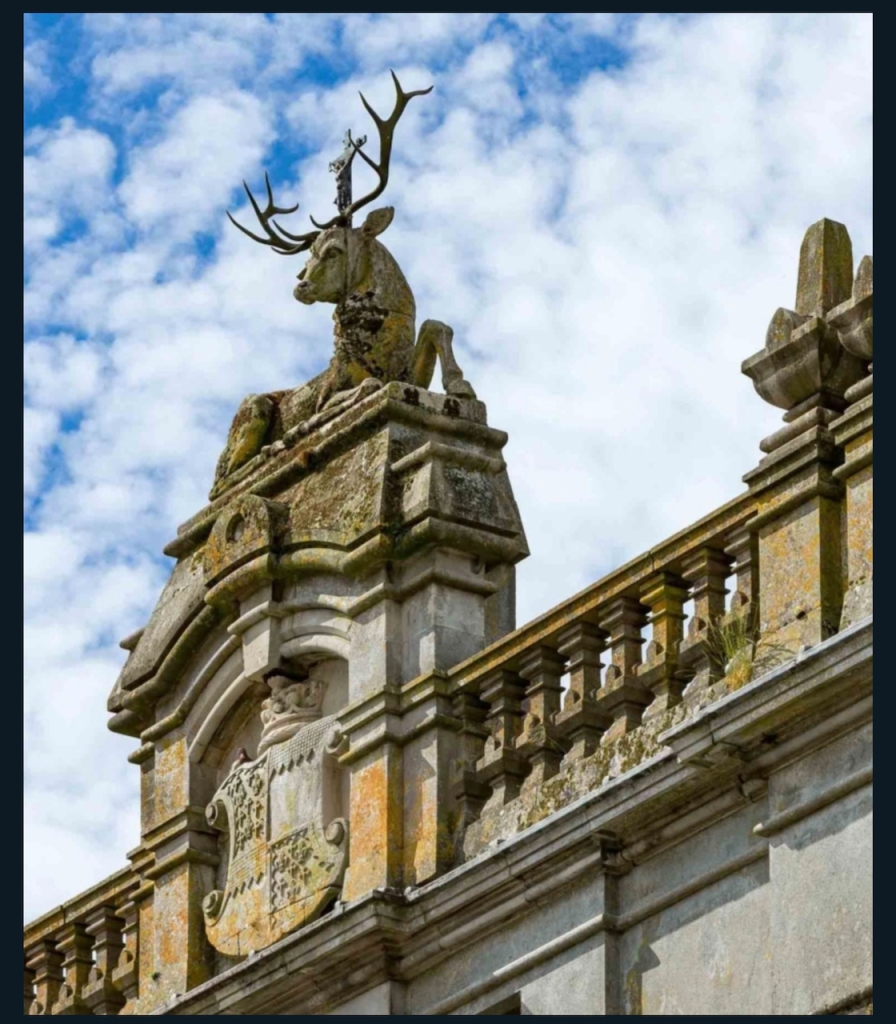

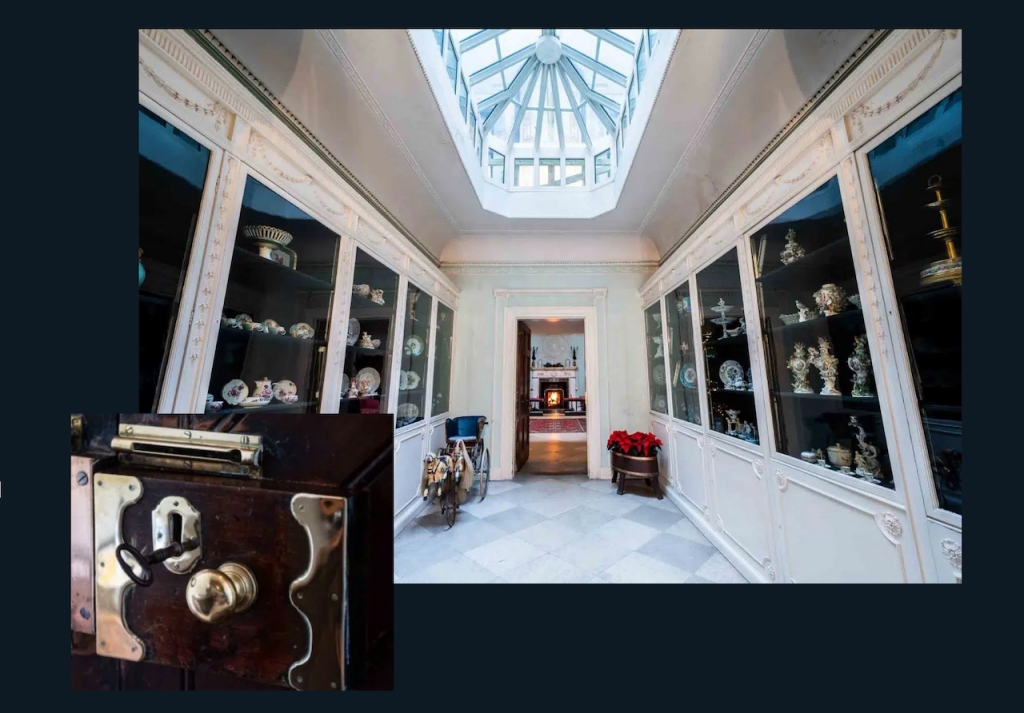

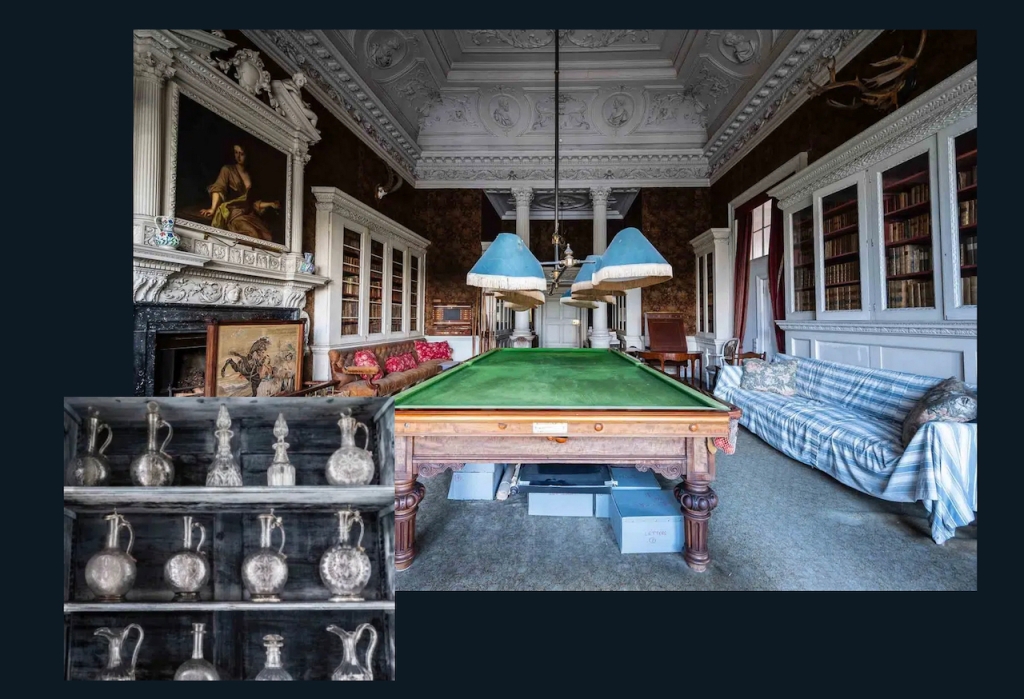

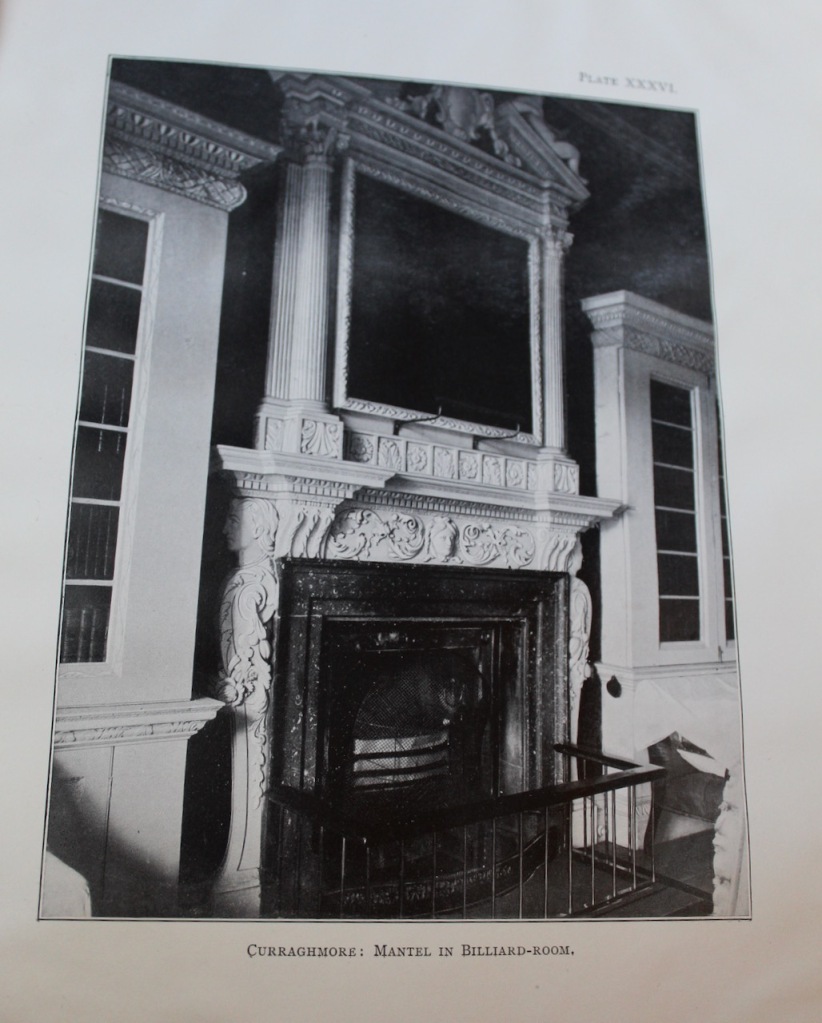

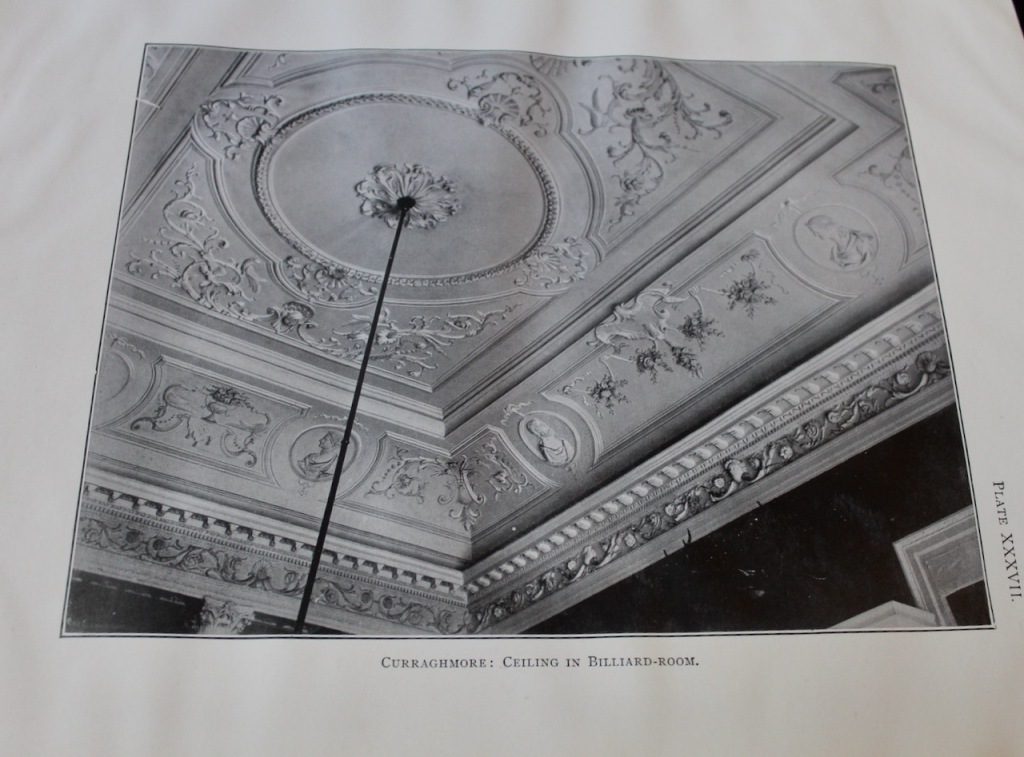

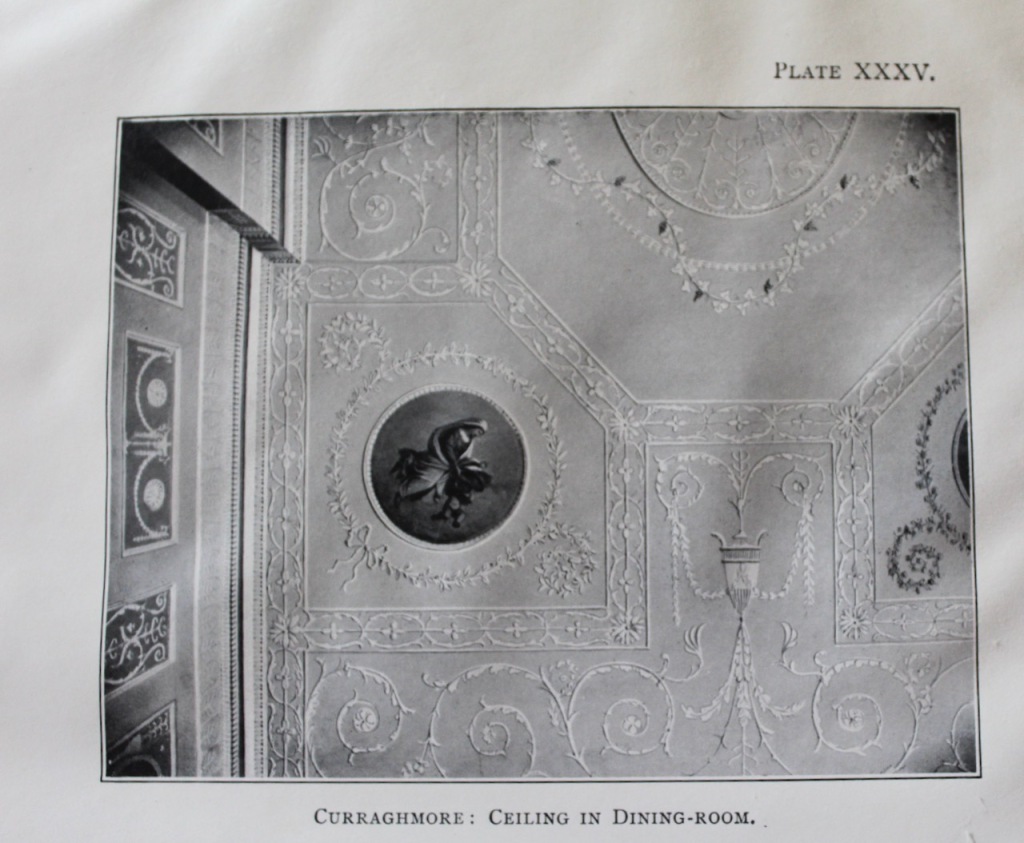

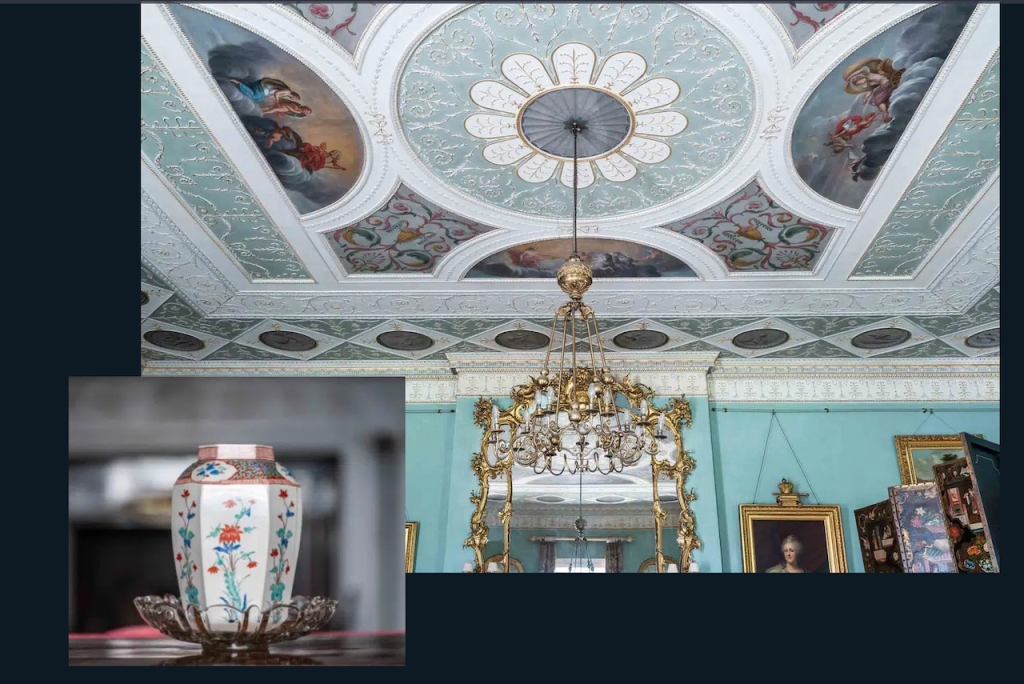

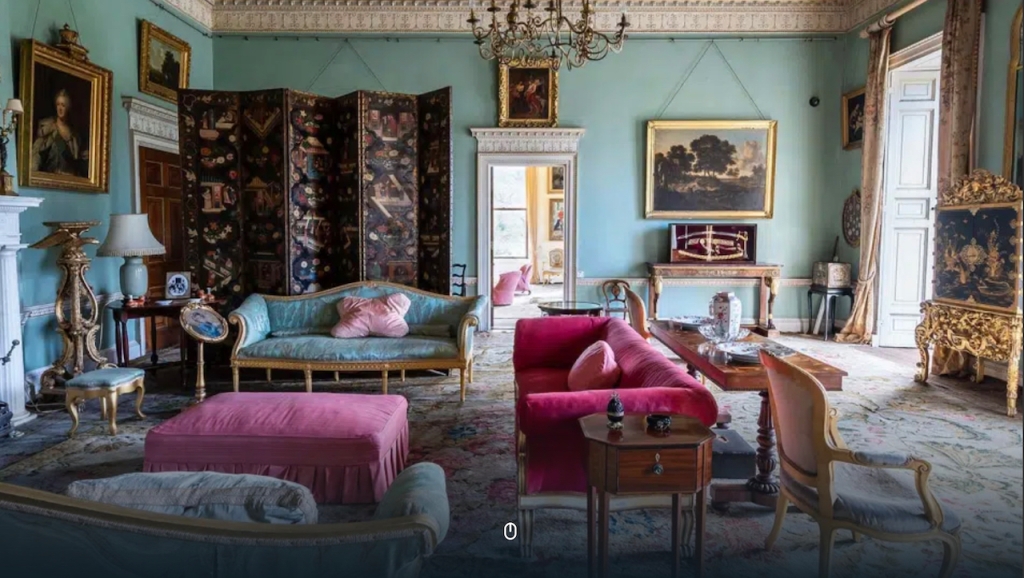

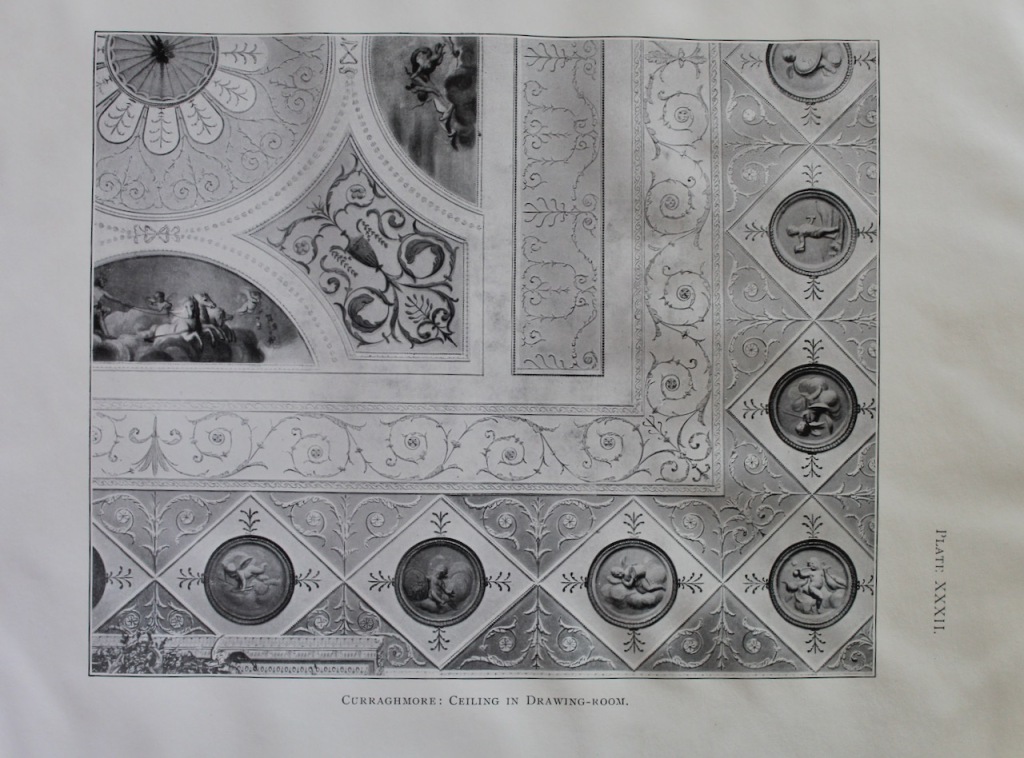

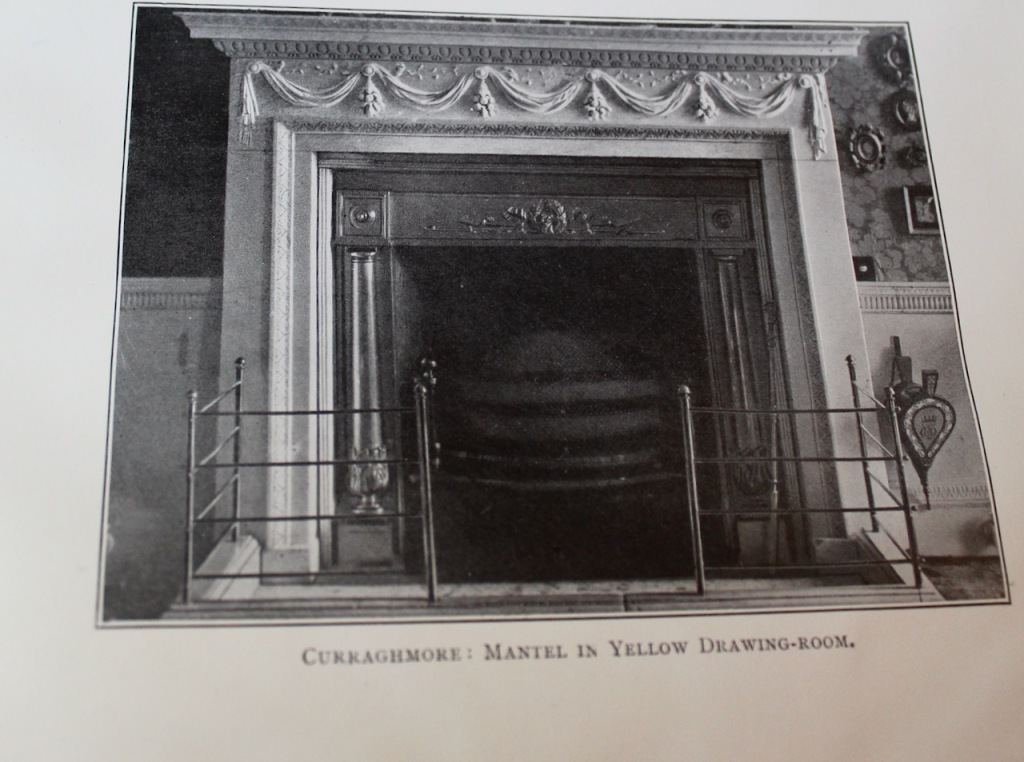

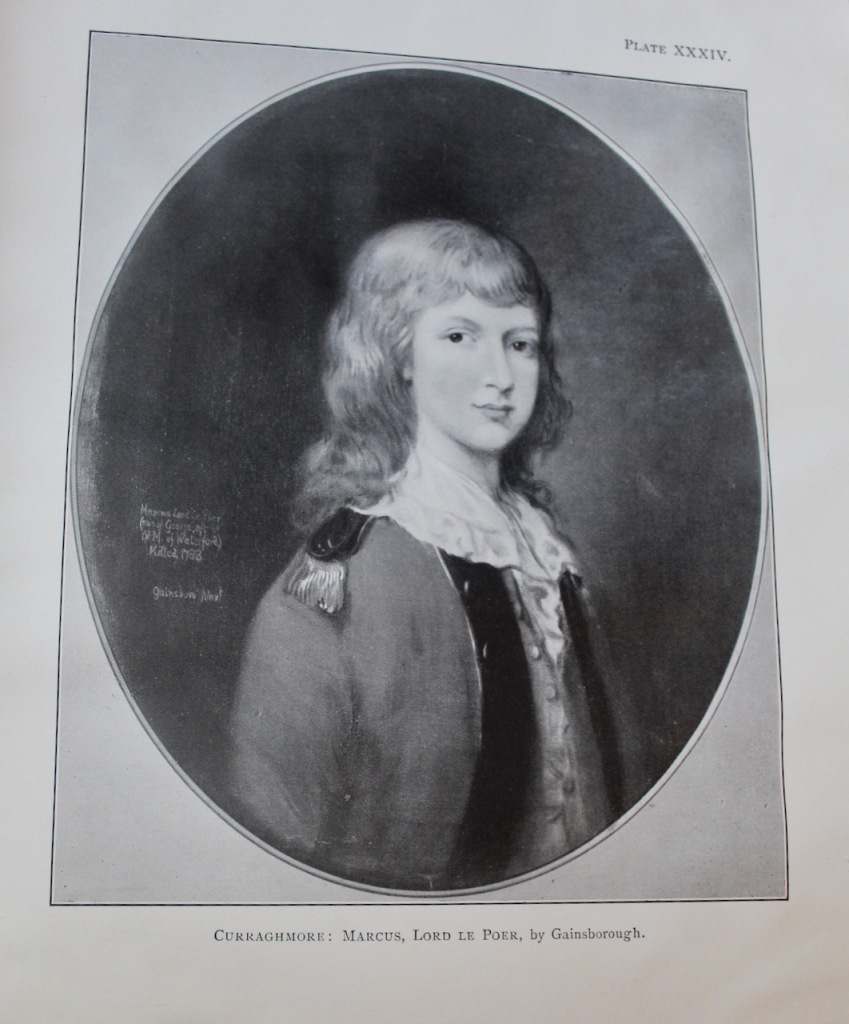

5. Curraghmore House, Portlaw, Co. Waterford – section 482

See my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/08/01/curraghmore-portlaw-county-waterford/

www.curraghmorehouse.ie

Open dates in 2024: May, June, July, Sept, Fri-Sun and Bank Holidays, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25,10am-4pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student, house/garden/shell house tour €22, garden €9, child under12

years free

6. Dromana House, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford – section 482

See my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/02/06/dromana-house-cappoquin-co-waterford/

www.dromanahouse.com

Open dates in 2024: June 1-July 31, Tues-Sun and Bank Holidays, Aug 17-25, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student, house €10, garden €6, both €15, child under 12 years free, R.H.S.I members 50% off

7. Dungarvan Castle, Waterford – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/11/07/office-of-public-works-properties-in-munster-counties-kerry-and-waterford/

8. Fairbrook House, Garden and Museum, County Waterford

https://www.fairbrook-housegarden.com/

The website tells us: “Fairbrook House garden and museum, Kilmeaden, Co.Waterford, Ireland X91FN83 A romantic walled garden at the river Dawn laid out between ruins of the former Fairbrook Mill (since 1700). OPEN MAY – SEPTEMBER”

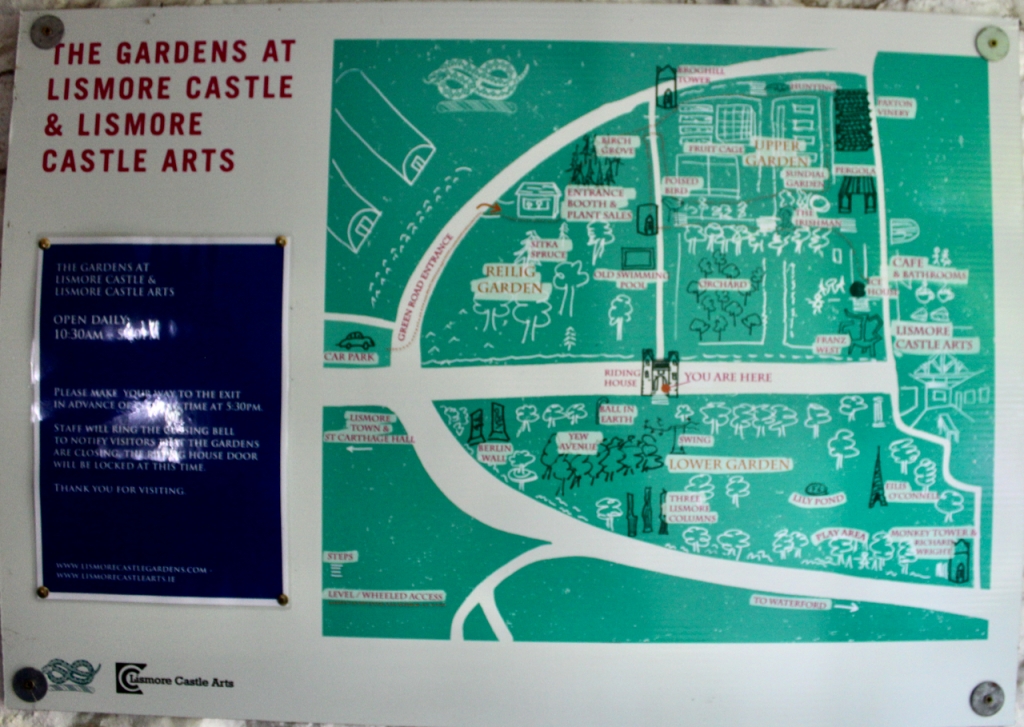

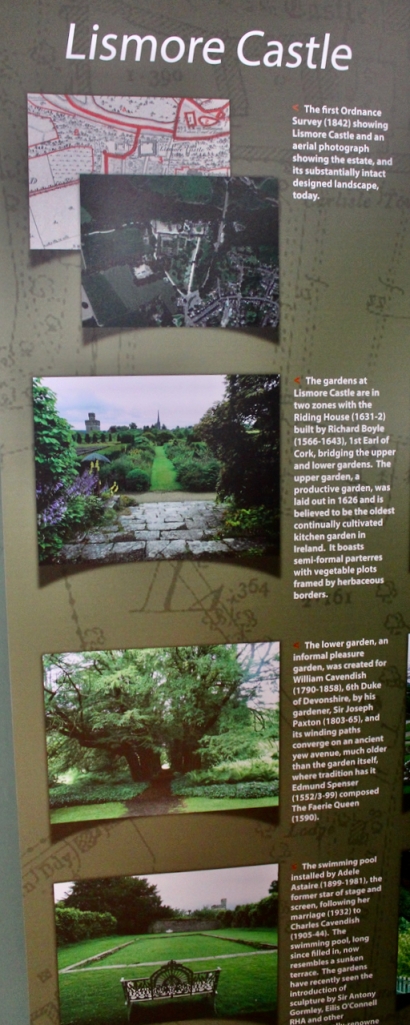

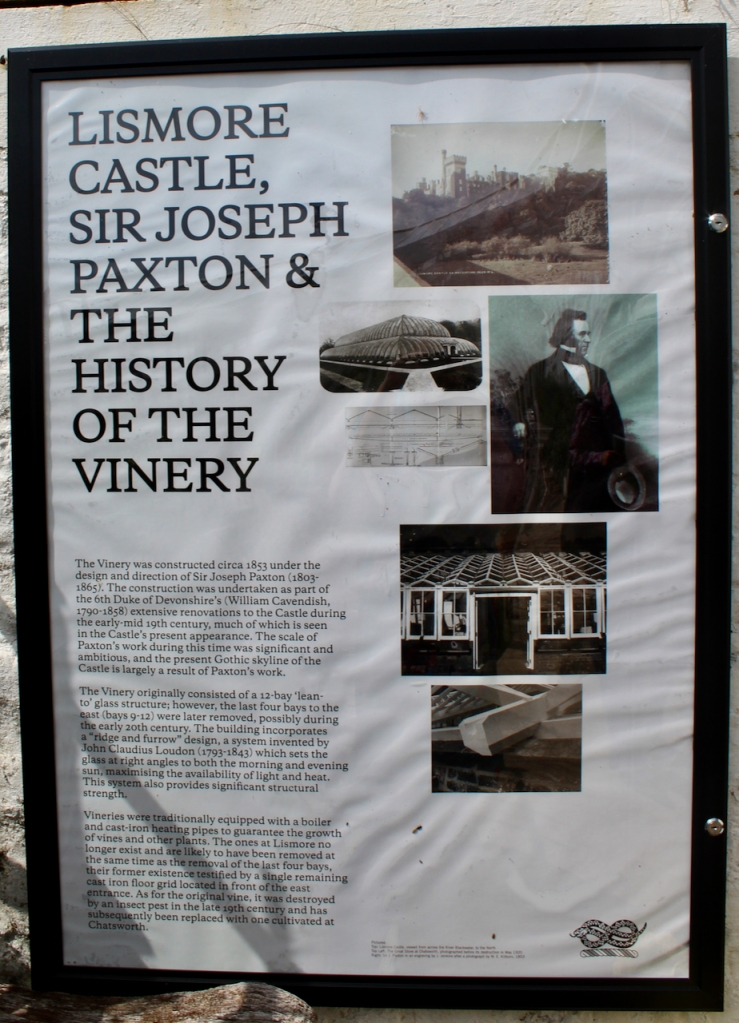

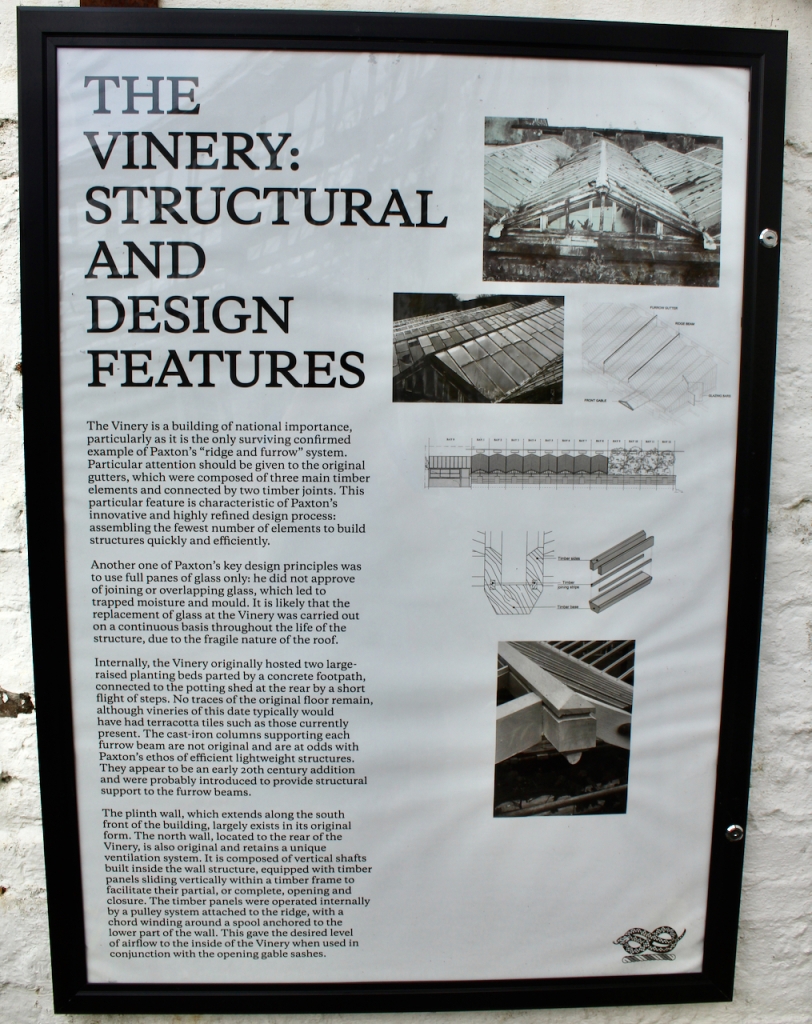

9. Lismore Castle Gardens

https://www.discoverireland.ie/waterford/lismore-castle-gardens

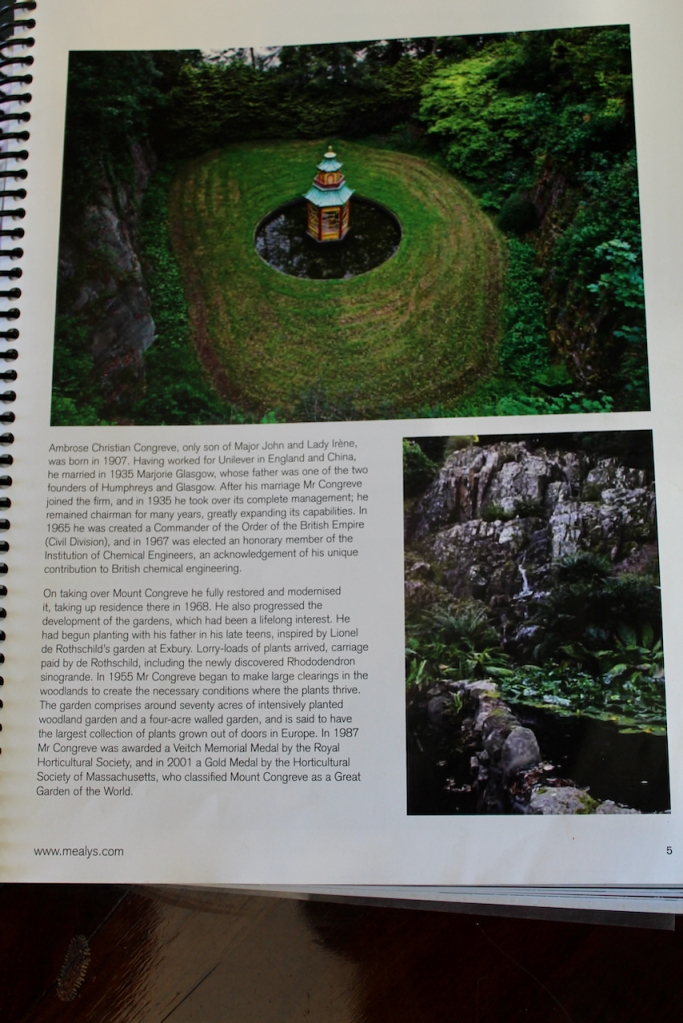

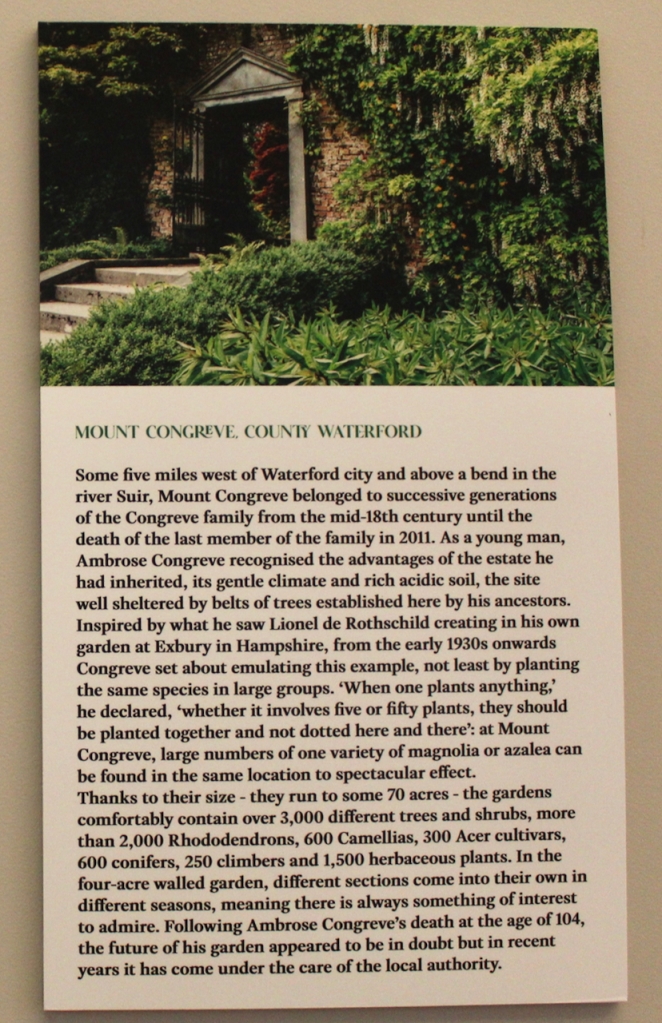

10. Mount Congreve Gardens, County Waterford

The website tells us: “Mount Congreve House and Gardens situated in Kilmeaden, Co. Waterford, in Ireland’s Ancient East is home to one of “the great gardens of the World”. Mount Congreve House, home to six generations of Congreves, was built in 1760 by the celebrated local architect John Roberts.

“The Gardens comprise around seventy acres of intensively planted woodland, a four acre walled garden and 16 kilometres of walkways. Planted on a slight incline overlooking the River Suir, Mount Congreve’s entire collection consists of over three thousand different trees and shrubs, more than two thousand Rhododendrons, six hundred Camellias, three hundred Acer cultivars, six hundred conifers, two hundred and fifty climbers and fifteen hundred herbaceous plants plus many more tender species contained in the Georgian glasshouse.“

The house was built for John Congreve (1730-1801), who held the office of High Sheriff of County Waterford in 1755. His grandfather John was Rector of Kilmacow, County Kilkenny, and his father Ambrose (1698-1741) played a leading role in the affairs of Waterford city. When Ambrose died his widow married Dr. John Whetcombe, Bishop of Clonfert and later Archbishop of Cashel.

John Congreve (1730-1801) married Mary Ussher, daughter of Beverly Ussher, MP, who lived at Kilmeadon, County Waterford.

Mark Bence-Jones tells us of Mount Congreve (1988):

p. 213. “(Congreve/IFR) An C18 house [the National Inventory says c. 1750] consisting of three storey seven bay centre block with two storey three bay overlapping wings; joined to pavilions by screen walls with arches on the entrance front and low ranges on the garden front, where the centre block has a three bay breakfront and an ionic doorcase. The house was remodelled and embellished ca 1965-69, when a deep bow was added in the centre of the entrance front, incorporating a rather Baroque Ionic doorcase, and the pavilions were adorned with cupolas and doorcases with broken pediments. Other new features include handsome gateways flanking the garden front at either end and a fountain with a statue in one of the courtyards between the house and pavilions. The present owner has also laid out magnificent gardens along the bank of the River Suir which now extends to upwards of 100 acres; with large scale plantings of rare trees and shrubs, notably rhododendrons and magnolias. The original walled gardens contains an eighteenth century greenhouse.”

Ambrose Ussher Congreve (1767-1809) inherited the estate and married Anne Jenkins.

Ambrose and Anne’s son John (1801-1863) was their heir.

Ambrose and Anne’s daughter Jane married John Cooke of Kiltinane Castle in County Tipperary. Daughter Mary married Reverend John Thomas Medlycott who lived in Rockett’s Castle in Portlaw, County Waterford. Their son Ambrose died unmarried.

John was Deputy Lieutenant and also High Sheriff of County Waterford. He married Louisa Harriet Dillon from Clonbrock in County Galway, daughter of Luke Dillon (1780-1826) 2nd Baron Clonbrock.

Their son Ambrose (1832-1901) inherited the estate, and he also held the positions of Deputy Lieutenant and High Sheriff for County Waterford. He married a cousin, Alice Elizabeth, daughter of Robert 3rd Baron Clonbrock.

John (1872-1957) the son of Ambrose and Alice Elizabeth joined the military and fought in World War I. He married Helena Blanche Irene, daughter of Edward Ponsonby 8th Earl of Bessborough in County Kilkenny. Their son Ambrose Christian (1907-2011) worked for Unilever and then with the firm founded by his father-in-law, Humphreys and Glasgow. He inherited Mount Congreve and developed and improved the garden. In April 2011 Mr. Congreve was in London en route to the Chelsea Flower Show, aged 104, when he died. He married but had no children. The estate was left in Trust for the Irish people.

Mount Congreve Gardens was closed for new development works but has reopened. An article by Ann Power in the Mount Congreve blog, 22nd Sept 2021, tells us:

“The 70-acre Mount Congreve Gardens overlooking the River Suir and located around 7km from the centre of Waterford City will close on October 10th 2021. The closure is to facilitate the upcoming works on Mount Congreve House and Gardens as it will be redeveloped into a world-class tourism destination with an enhanced visitor experience which is set to open for summer 2022.

“Funding of €3,726,000 has been approved under the Rural Regeneration Development Fund with additional funding from Failte Ireland and Waterford City & County Council for the visitor attraction, which is home to one of the largest private collections of plants in the world. The redevelopment and restoration of the Estate is set to provide enhanced visitor amenities including the repair of the historic greenhouse, improved access to grounds and pathways, and provision of family-friendly facilities. Car parking & visitor centre with cafe & retail.

“The project is planned for completion in 2022 and will create a new visitor centre featuring retail, food and beverage facilities, kitchens, toilets, and a ticket desk while also opening up new areas of the estate to the public including parts of the main house which has never been accessible to the public before.“

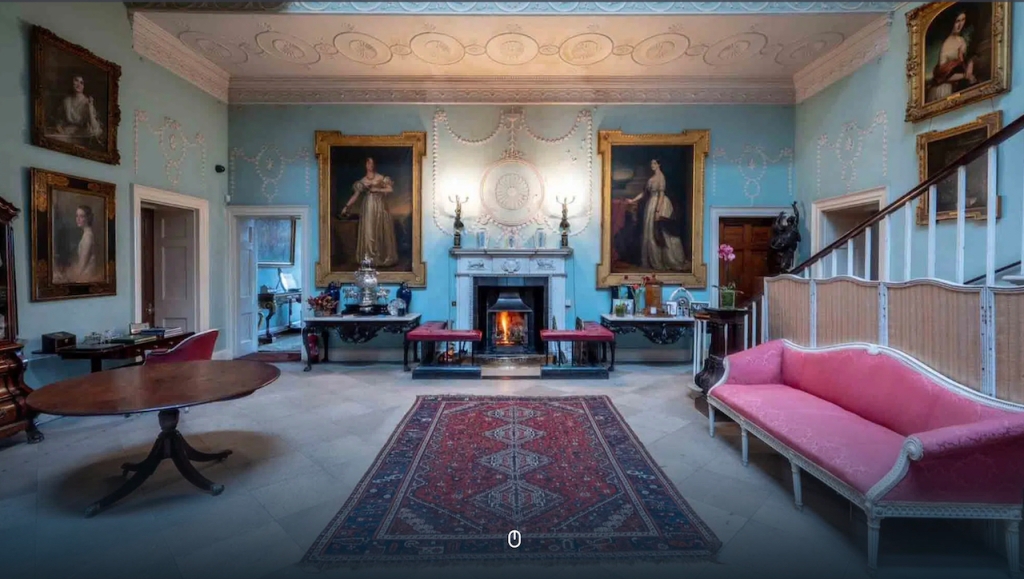

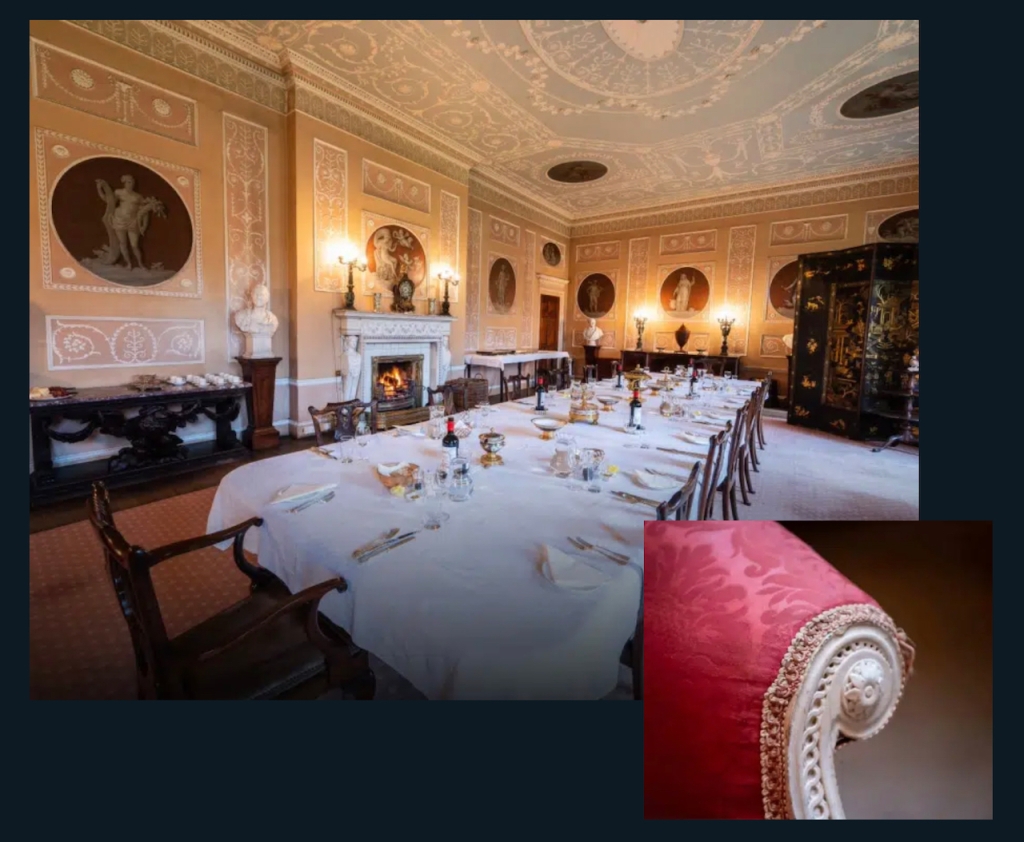

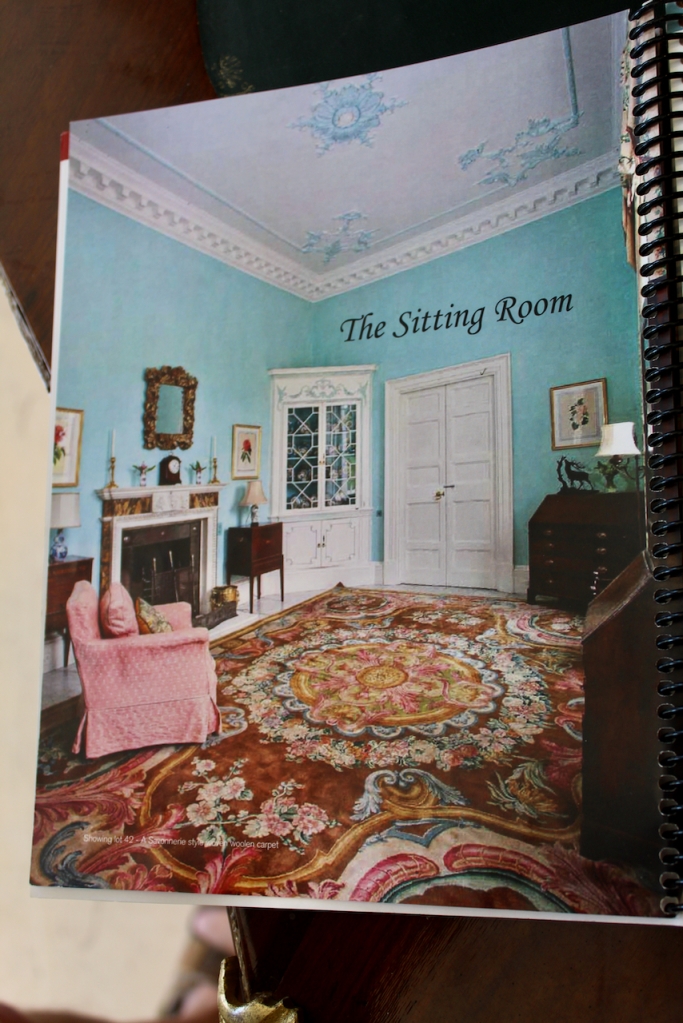

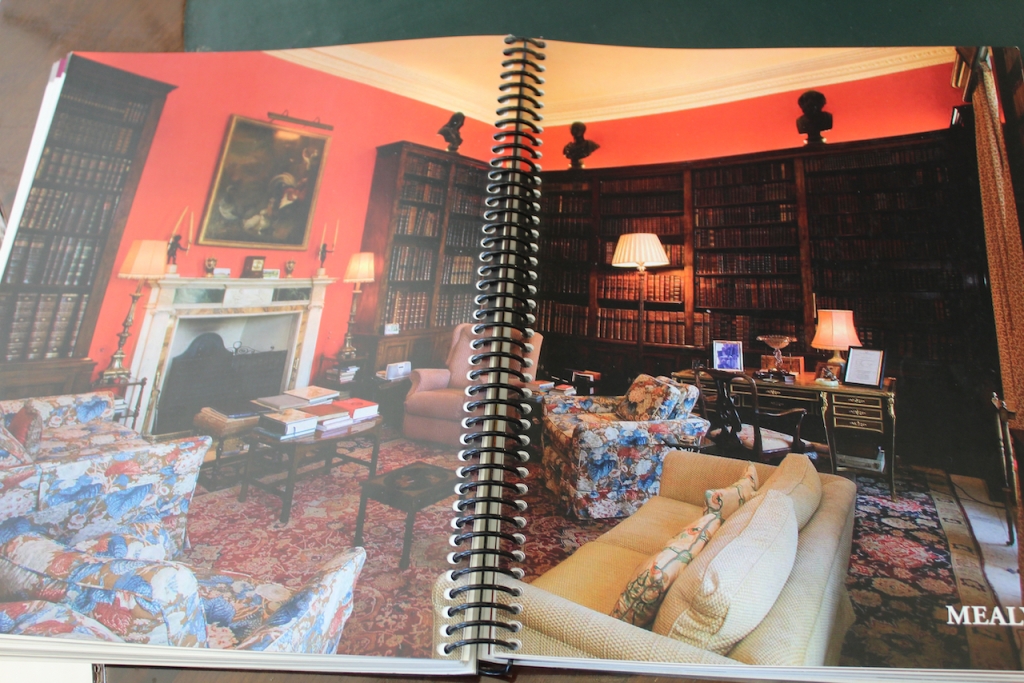

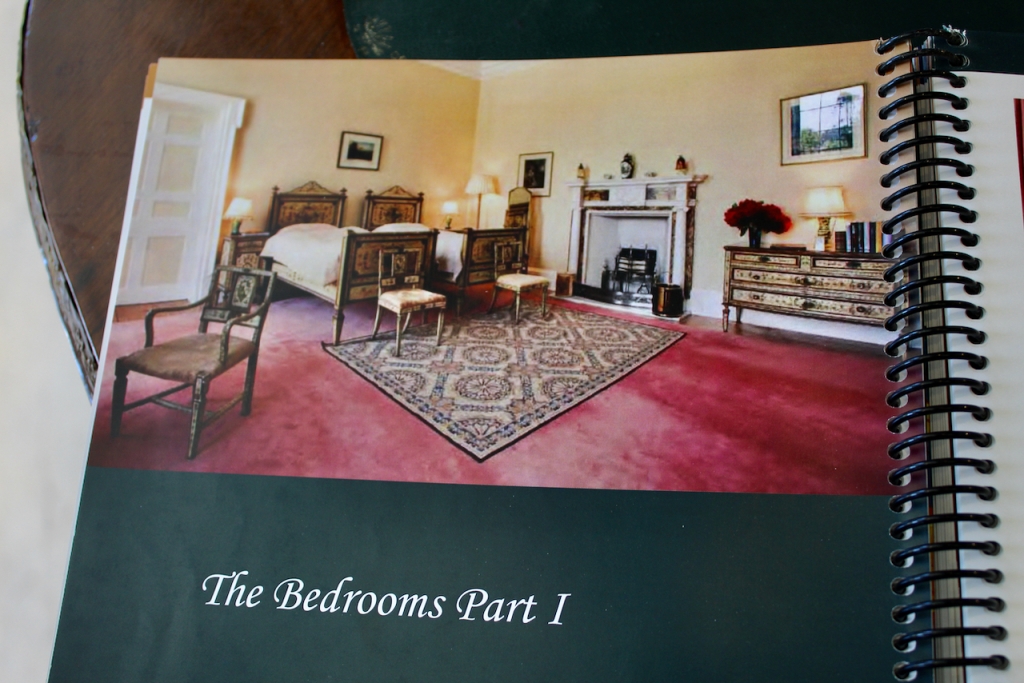

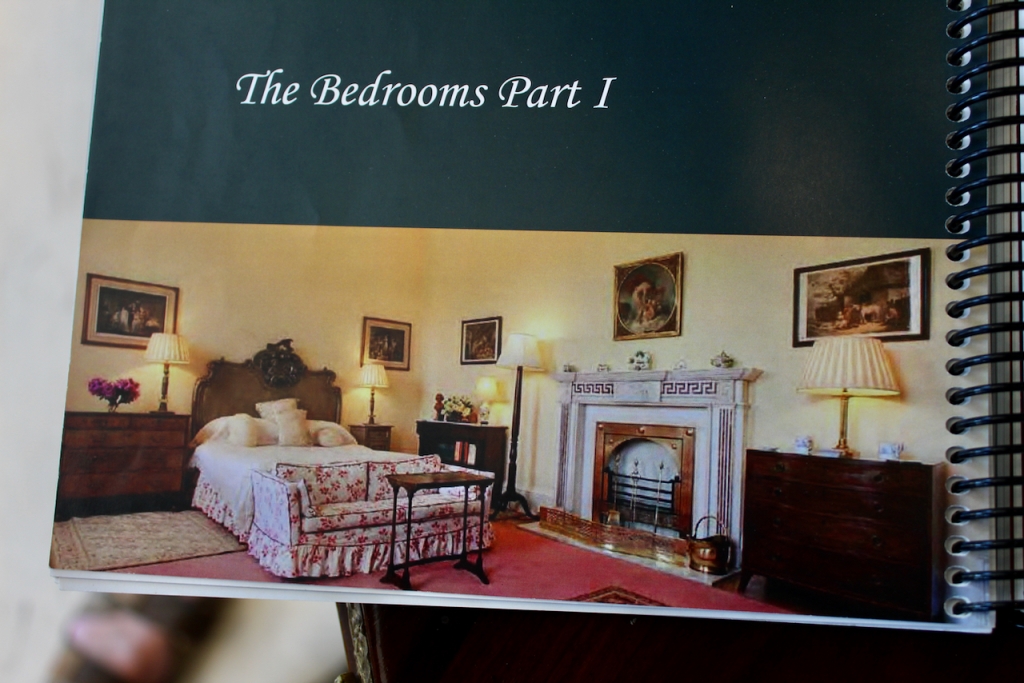

Unfortunately when we arrived, most of the house was closed! I have to make do with pictures of the rooms from the auction catalogue.

The staircase is off the front hall.

We were able to peer into the sitting room, off the front hall.

The website tells us: “The Woodland gardens at Mount Congreve were founded on the inspiration, generosity and encouragement of Mr. Lionel N. de Rothschild. He became arguably, the greatest landscaper of the 20th Century and one of the cleverest hybridists. He died in 1942. The original gardens at Mount Congreve had comprised of a simple terraced garden with woodland of ilexes and sweet chestnuts on the slopes falling down to the river. The Gardens are held in Trust for the State.

“The original gardens at Mount Congreve had comprised of a simple terraced garden with woodland of ilexes and sweet chestnuts on the slopes falling down to the river. Ambrose Congreve began planting parts of these in his late teens but it was not until 1955 that he began to make large clearings in the woodlands to create the necessary conditions where his new plants would thrive. With the arrival of Mr. Herman Dool in the early sixties, the two men began the process that would lead to Mount Congreve’s recognition as one of the ‘Great Gardens of the World’. Up to the very last years of his life, Mr Congreve could be found in the gardens dispensing orders and advice relating to his beloved plants.“

11. The Presentation Convent, Waterford Healthpark, Slievekeel Road, Waterford – section 482

Open dates in 2024: Jan 2-31, Feb 1-4, 6-29, Mar 1-17, 19-28, 30-31, April 2-30, May 1-5, 7-31, June 4-28, July 1-31, Aug 1-4, 6-30, Sept 2-30, Oct 1-27, 29-31, Nov 1-29, Dec 2-23, 27-30, closed Bank Holidays, 8.30am-5.30pm

Fee: Free

The National Inventory tells us it is a:

“Detached ten-bay two-storey over basement Gothic Revival convent, built 1848 – 1856, on a quadrangular plan about a courtyard comprising eight-bay two-storey central block with two-bay two-storey gabled advanced end bays to north and to south, ten-bay two-storey over part-raised basement wing to south having single-bay four-stage tower on a circular plan, eight-bay two-storey recessed wing to east with single-bay two-storey gabled advanced engaged flanking bays, six-bay double-height wing to north incorporating chapel with two-bay single-storey sacristy to north-east having single-bay single-storey gabled projecting porch, and three-bay single-storey wing with dormer attic to north…

“An attractive, substantial convent built on a complex plan arranged about a courtyard. Designed by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812 – 1852) in the Gothic Revival style, the convent has been well maintained, retaining its original form and character, together with many important salient features and materials. However, the gradual replacement of the original fittings to the openings with inappropriate modern articles threatens the historic character of the composition. The construction of the building reveals high quality local stone masonry, particularly to the cut-stone detailing, which has retained its original form. A fine chapel interior has been well maintained, and includes features of artistic design distinction, including delicate stained glass panels, profiled timber joinery, including an increasingly-rare rood screen indicative of high quality craftsmanship, and an open timber roof construction of some technical interest. The convent remains an important anchor site in the suburbs of Waterford City and contributes to the historic character of an area that has been substantially developed in the late twentieth century.” [7]

12. Reginald’s Tower, County Waterford – OPW

See my OPW write-up:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/01/19/office-of-public-works-properties-munster/

13. Tourin House & Gardens, Tourin, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford P51 YYIK – section 482

See my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/04/30/tourin-house-gardens-cappoquin-county-waterford/

www.tourin-house.ie

Open dates in 2024:

House, April 2- 30, May 1-31, June 4-29, Aug 1-31, Tue-Sat, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 1pm-5pm

Garden April- Sept, Tue-Sat, 1am-5pm

Fee: adult €6, OAP/student €4, child free.

Places to stay, County Waterford

1. Annestown House, County Waterford – B&B €

http://homepage.eircom.net/~annestown/welcome.htm

We were lucky to stay at the cottages at Annestown House in May 2023! I swam in the sea every day there, in the wonderful bay. The house was advertised for sale the following month.

It was a heavenly place to stay, as the setting was so lovely, and we were able to sit out and look at the view over the sea. Rabbits emerged on the lawn regularly, and I enjoyed sitting on a bench and watching them venture out across the lawn, which used to be a tennis court and croquet lawn.

The first part of the house seems to have been built around 1770 for Henry St. George Cole. The Landed Estates database tells us that he was a Justice of the Peace and a member of the Board of Waterford Port. His death is reported in contemporary newspapers in 1819. Mark Bence-Jones tells us it was bought around 1830 by the Palliser family.

The National Inventory gives us more detail on its construction: “Detached six-bay two-storey house with dormer attic, c.1820, retaining early fenestration with single-bay two-storey gabled entrance bay, single-bay two-storey gabled end bay having single-bay two-storey canted bay window, three-bay two-storey wing to north originally separate house, c.1770, and three-bay two-storey return to west. Extended, c.1920, comprising single-bay single-storey lean-to recessed end bay to south.“

Mark Bence-Jones tells us of Annestown:

p. 5. “(Palliser, sub Galloway/IFR) Rambling three storey house at right angles to the village street of Annestown, which is in fact two houses joined together. The main front of the house faces the sea; but it has a gable end actually on the street. Low-ceilinged but spacious rooms; long drawing room divided by an arch with simple Victorian plasterwork; large library approached by a passage. Owned at beginning of 19C by Henry St. George Cole, bought ca. 1830 by the Palliser family, from whom it was inherited by the Galloways.”

The advertisement by Savills Residential & Country Agency with myhome.ie describes the interior:

“Entering through a porch, this opens into an impressive hall, which offers access to the main reception rooms which include the dining room and drawing room which are most impressive. Located on the right wing of the house is the games room while on the left wing is the kitchen and breakfast room. A staircase in the rear hall leads up to the first floor where there is the master bedroom suite. There are 6 further bedrooms (two ensuite) and a bathroom on this level. On the second floor, there are two additional attic rooms and a shower room.…While the accommodation has been extended since its original construction, the house has been beautifully maintained with many notable period features which include hardwood floors, architraves, decorative fireplaces, sash and cash windows, cornices and ceiling roses.“

Timothy William Ferres tells us that Reverend John Bury Palliser (1791-1864) lived here. He was Rector of Clonmel. His father was John Palliser of Derryluskan, County Tipperary and his mother Grace Barton from Grove House in County Tipperary.

The Reverend Palliser married Julia Phillida Howe. Their son and heir was Wray Bury Palliser (1831-1906). A younger brother died aged just 25 in the China War, in China.

Wray was High Sheriff of County Waterford in 1883, Deputy Lieutenant and Justice of the Peace. He married Maria Victoria Josephine Gubbins, daughter of Joseph Gubbins of Kilfrush House in County Limerick. They had a daughter, Alice Grace Palliser who died aged only 15. The property therefore passed via a brother of Reverend John Bury Palliser, Wray Bury Palliser of Derryluskan, to his son William (1830-1882). William was in the military and married Anne Perham.

His daughter Mary Jane Sybil (1874-1940) married Major Harold Bessemer Galloway in 1908, who was from Scotland. Their son Ian Charles joined the military and lived in Tynte Park in County Wicklow and in Scotland. Their son Wray Bury Galloway (1914-1994) lived in Annestown. He married Mary Clayton Alcock from Wilton Castle in County Wexford – we have also stayed in Wilton Castle, a Section 482 property!

It remained with the Galloway family until 2008, Timothy William Ferres tells us. John and Pippa Galloway ran a restaurant in th house, and John had been restaurant manager in Waterford Castle hotel.

2. Ballyrafter House, Lismore, Co Waterford –

I’m not sure if this is still a hotel as it was advertised for sale in 2020. The Myhome website tells us: “Ballyrafter House was built circa 1830, on the commission of the Duke of Devonshire, one of the wealthiest men in England, whose Irish Seat is the nearby Lismore Castle. Initially intended for the Duke’s Steward, it soon became a hunting and fishing lodge for his guests.“

3. Cappoquin House holiday cottages

www.cappoquinhouseandgardens.com and on airbnb, https://www.airbnb.ie/rooms/16332970?adults=2&children=0&infants=0&pets=0&wishlist_item_id=11002218087407&check_in=2023-05-23&check_out=2023-05-24&source_impression_id=p3_1681134404_prgB5ShntjT0gCzp

4. Dromana, Co Waterford – 482, holiday cottages €

5. Faithlegg House, Waterford, Co Waterford – hotel €€

Mark Bence-Jones describes Faithlegg House (1988):

p. 123. (Power/IFR; Gallwey/IFR) A three storey seven bay block with a three bay pedimented breakfront, built 1783 by Cornelius Bolton, MP, whose arms, elaborately displayed, appear in the pediment. Bought 1819 by the Powers who ca 1870 added two storey two bay wings with a single-storey bow-fronted wings beyond them. At the same time the house was entirely refaced, with segmental hoods over the ground floor windows; a portico or porch with slightly rusticated square piers was added, as well as an orangery prolonging one of the single-storey wings. Good C19 neo-Classical ceilings in the principal rooms of the main block, and some C18 friezes upstairs. Sold 1936 by Mrs H.W.D. Gallwey (nee Power); now a college for boys run by the De La Salle Brothers.”

The Faithlegg website tells us that the house was probably built by John Roberts (1714-1796): “a gifted Waterford architect who designed the Waterford’s two Cathedrals, City Hall, Chamber of Commerce and Infirmary. He leased land from Cornelius Bolton at Faithlegg here he built his own house which he called Roberts Mount. He built mansions for local gentry and was probably the builder of Faithlegg House in 1783.”

The website tells us of more about the history of the house:

“Faithlegg stands at the head of Waterford Harbour, where the three sister rivers of the Barrow, Nore and Suir meet. As a consequence, it has been to the fore in the history of not just Waterford but also Ireland. For it was via the harbour and these rivers that the early settlers entered and from the hill that we stand under, the Minaun, that the harbour was monitored. Here legend tells us sleeps the giant Cainche Corcardhearg son of Fionn of the Fianna who was stationed here to keep a watch over Leinster.

“A Norman named Strongbow landed in the harbour in 1170 and this was followed by the arrival of Henry II in October 1171. Legend has it that Henry’s fleet numbered 600 ships and one of the merchants who donated to the flotilla was a Bristol merchant named Aylward. He was handsomely rewarded with the granting of 7000 acres of land centred in Faithlegg. The family lived originally in a Motte and Baily enclosure the remains of which is still to be seen. This was followed by Faithlegg Castle and the 13th century church in the grounds of the present Faithlegg church dates from their era too. The family ruled the area for 500 years until they were dispossessed in 1649 by the armies of Oliver Cromwell. The property was subsequently granted to a Cromwellian solider, Captain William Bolton.

“Over a century later in 1783 the present house was commenced by Cornelius Bolton who had inherited the Faithlegg Estate from his father in 1779. Cornelius was an MP, a progressive landlord and businessman. Luck was not on his side however and financial difficulties followed. In 1819 the Bolton family sold the house and lands to Nicholas and Margaret Mahon Power, who had married the year before. It was said that Margaret’s dowry enabled the purchase. The Powers adorned the estate with the stag’s head and cross, which was the Power family crest. It remains the emblem of Faithlegg to this day.”

Margaret, the website tells us, was the only daughter and heiress of Nicholas Mahon of Dublin. She married Nicholas Power in 1818 and the couple came to live in Faithlegg. It was not a happy marriage and, following a legal separation in 1860, she returned to live in Dublin where she died in 1866.

“The House passed to Hubert Power, the only son of Pat & Lady Olivia Power, and in 1920 upon Hubert’s death, it passed to his daughter Eily Power, in 1935 Eily and her husband sold the House to the De la Salle order of teaching brothers after which it acted as a junior novitiate until 1986.

“The last remaining gap in history is from 1980’s until 1998 when it was taken over by FBD Property and Leisure Group.“

6. Fort William, County Waterford, holiday cottages

Mark Bence-Jones tells us of Fort William (1988):

p. 126. “Gumbleton, sub Maxwell-Gumbleton/LG1952; Grosvenor, Westminster, B/PB) A two storey house of sandstone ashlar with a few slight Tudor-Revival touches, built 1836 for J. B. [John Bowen] Gumbleton to the design of James & George Richard Pain. Three bay front with three small gables and a slender turret-pinnacle at either side; doorway recessed in segmental-pointed arch Georgian glazed rectangular sash windows with hood mouldings. Tudor chimneys. Other front of seven bays; plain three bay side elevation. Large hall, drawing room with very fine Louis XI boiseries, introduced by 2nd Duke of Westminster, Fort William was his Irish home from ca 1946 to his death in 1953. Afterwards the house of Mr and Mrs Henry Drummond-Wolff, then Mr and Mrs Murray Mitchell.”

The Historic Houses of Ireland gives us more detail about the house, including explaining its name:

“In the early eighteenth century the Gumbleton family, originally from Kent, purchased an estate beside the River Blackwater in County Waterford, a few miles upstream from Lismore. The younger son, William Conner Gumbleton, inherited a portion of the estate and built a house named Fort William, following the example of his cousin, Robert Conner, who had called his house in West Cork Fort Robert. The estate passed to his nephew, John Bowen Gumbleton, who commissioned a new house by James and George Richard Pain, former apprentices of John Nash with a thriving architectural practice in Cork.

“Built in 1836, in a restrained Tudor Revival style, the new house is a regular building of two stories in local sandstone with an abundance of gables, pinnacles and tall Elizabethan chimneys. The interior is largely late-Georgian and Fortwilliam is essentially a classical Georgian house with a profusion of mildly Gothic details.

“Gumbleton’s son died at sea and his daughter Frances eventually leased the house to Colonel Richard Keane, brother of Sir John from nearby Cappoquin House. The Colonel was much annoyed when his car, reputedly fitted with a well-stocked cocktail cabinet, was commandeered by the IRA so he permitted Free State troops to occupy the servants’ wing at Fortwilliam during the Civil War, which may have influenced the Republican’s decision to burn his brother’s house in 1923.

“When Colonel Keane died in a shooting accident, the estate reverted to Frances Gumbleton’s nephew, John Currey, and was sold to a Mr Dunne, who continued the tradition of letting the house. His most notable tenant was Adele Astaire, sister of the famous dancer and film star Fred Astaire, who became the wife of Lord Charles Cavendish from nearby Lismore Castle.

“In 1944 the Gumbleton family repurchased Fortwilliam but resold for £10,000 after just two years. The new owner was Hugh Grosvenor, second Duke of Westminster and one of the world’s wealthiest men. His nickname ‘Bend or’ was a corruption of the heraldic term Azure, a bend or, arms the Court of Chivalry had forced his ancestor to surrender to Lord Scroope in 1389 and still a source of irritation after six hundred years. Already thrice divorced, the duke’s name had been linked to a number of fashionable ladies, including the celebrated Parisian couturier Coco Chanel.

“Fortwilliam is in good hunting country with some fine beats on a major salmon river, which allowed the elderly duke to claim he had purchased an Irish sporting base. Its real purpose, however, was to facilitate his pursuit of Miss Nancy Sullivan, daughter of a retired general from Glanmire, near Cork, who soon became his fourth duchess.

“They made extensive alterations at Fortwilliam, installing the fine gilded Louis XV boiseries in the drawing room, removed from the ducal seat at Eaton Hall, in Cheshire, and fitting out the dining room with panelling from one of his sumptuous yachts. He died in 1953 but his widow survived for a further fifty years, outliving three of her husband’s successors at Eaton Lodge in Cheshire. Anne, Duchess of Westminster was renowned as one of the foremost National Hunt owners of the day. Her bay gelding, Arkle, won the Cheltenham Gold Cup on three successive occasions and is among the most famous steeplechasers of all time.

“Fortwilliam was briefly owned by the Drummond-Wolfe family before passing to an American, Mr. Murray Mitchell. On his widow’s death it was purchased by Ian Agnew and his wife Sara, who undertook a sensitive restoration before he too died in 2009. In 2013 the estate was purchased by David Evans-Bevan who lives at Fortwilliam today with his family, farming and running the salmon fishery.“

7. Gaultier Lodge, Woodstown, Co Waterford €€

The website tells us that

“Gaultier Lodge is an 18th Century Georgian Country House designed by John Roberts, which overlooks the beach at Woodstown on the south east coast of Co. Waterford in Ireland. Enjoy high quality bed and breakfast guest accommodation next to the beach and Waterford Bay. Relax and unwind in the tastefully decorated rooms and warm inviting bedrooms. Enjoy an Irish breakfast each morning.”

8. Richmond House, Cappoquin, Co Waterford – guest house

https://www.richmondcountryhouse.ie

“The Earl of Cork built Richmond House in 1704. Refurbished and restored each of the 9 bedrooms feature period furniture and warm, spacious comfort. All rooms are ensuite and feature views of the extensive grounds and complimentary Wi-Fi Internet access is available throughout the house. An award winning 18th century Georgian country house, Richmond House is situated in stunning mature parkland surrounded by magnificent mountains and rivers.

“Richmond House facilities include a fully licensed restaurant with local and French cuisine. French is also spoken at Richmond House. Each bedroom offers central heating, direct dial telephone, television, trouser press, complimentary Wi-Fi Internet access, tea-and coffee-making facilities and a Richmond House breakfast.”

In his book Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988) Mark Bence-Jones describes it: “a three storey late Georgian block. Five bay front with Doric porch; three bay side. Eaved roof on bracket cornice. In 1814, the residence of Michael Keane; in 1914, of Gerald Villiers-Stuart.“

9. Salterbridge Gate Lodge, County Waterford €

https://www.irishlandmark.com/property/salterbridge-gatelodge/

See my write-up about Salterbridge, previously on the Section 482 list but no longer:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/04/16/salterbridge-house-and-garden-cappoquin-county-waterford/

and www.salterbridgehouseandgarden.com

10. Waterford Castle, The Island, Co Waterford €€

https://www.waterfordcastleresort.com

The Archiseek website tells us that Waterford Castle is: “A small Norman keep that was extended and “restored” in the late 19th century. An initial restoration took place in 1849, but it was English architect W.H. Romaine-Walker who extended it and was responsible for its current appearance today. The original keep is central to the composition with two wings added, and the keep redesigned to complete the composition.“

The National Inventory adds: “Detached nine-bay two- and three-storey over basement Gothic-style house, built 1895, on a quasi H-shaped plan incorporating fabric of earlier house, pre-1845, comprising three-bay two-storey entrance tower incorporating fabric of medieval castle, pre-1645…A substantial house of solid, muscular massing, built for Gerald Purcell-Fitzgerald (n. d.) to designs prepared by Romayne Walker (n. d.) (supervised by Albert Murrary (1849 – 1924)), incorporating at least two earlier phases of building, including a medieval castle. The construction in unrefined rubble stone produces an attractive, textured visual effect, which is mirrored in the skyline by the Irish battlements to the roof. Fine cut-stone quoins and window frames are indicative of high quality stone masonry. Successfully converted to an alternative use without adversely affecting the original character of the composition, the house retains its original form and massing together with important salient features and materials, both to the exterior and to the interior, including fine timber joinery and plasterwork to the primary reception rooms.”

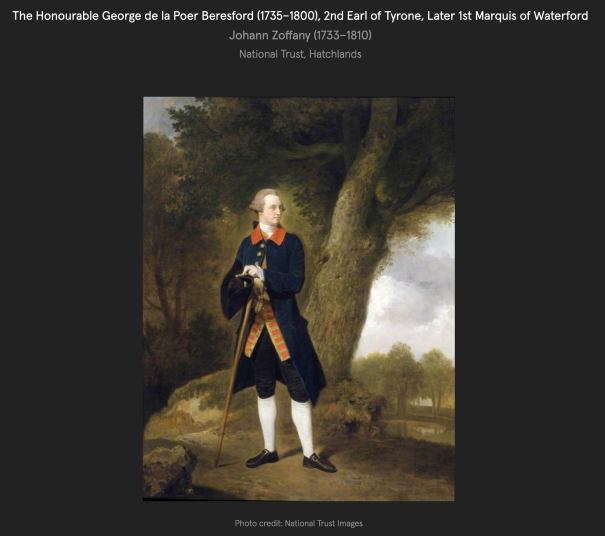

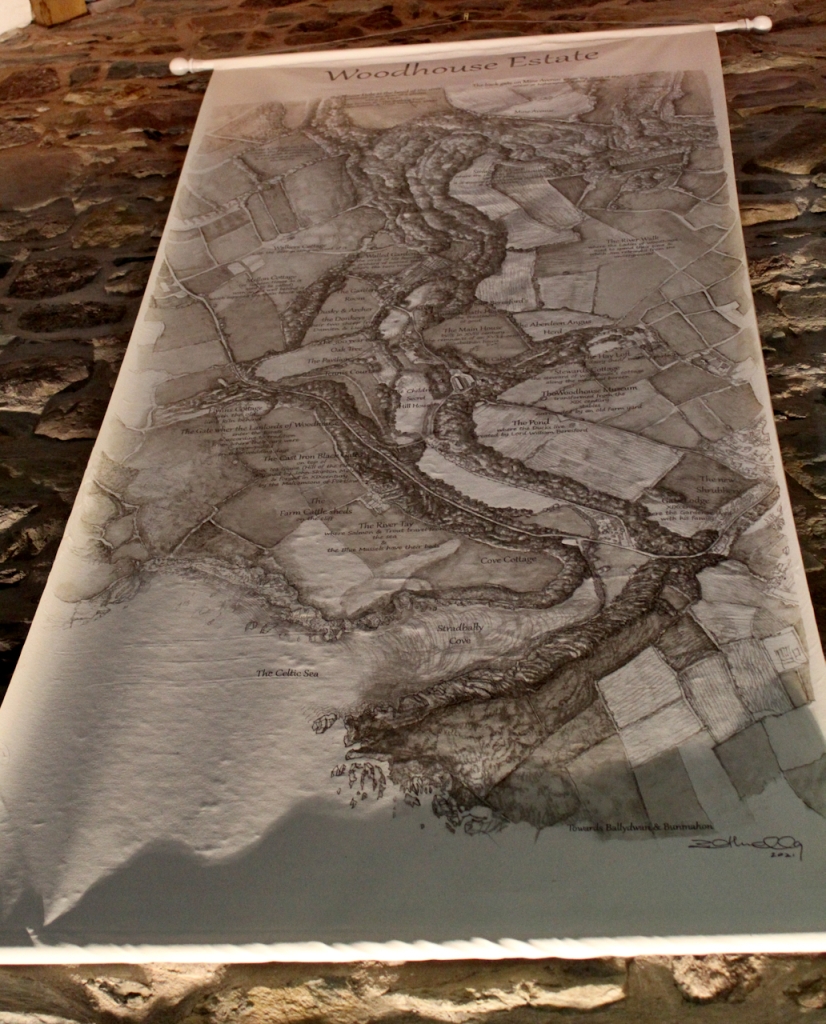

11. Woodhouse, County Waterford – gate lodge and cottages

We visited Woodhouse on a day trip with the Cork Chapter of the Irish Georgian Society on a gloriously sunny day on May 24th, 2023. The home owners Jim and Sally Thompson welcomed us into their home, and historian Marianna Lorenc delivered a wonderful talk about the history of the house and the family who lived there.

You can stay in the gate lodge or cottages.

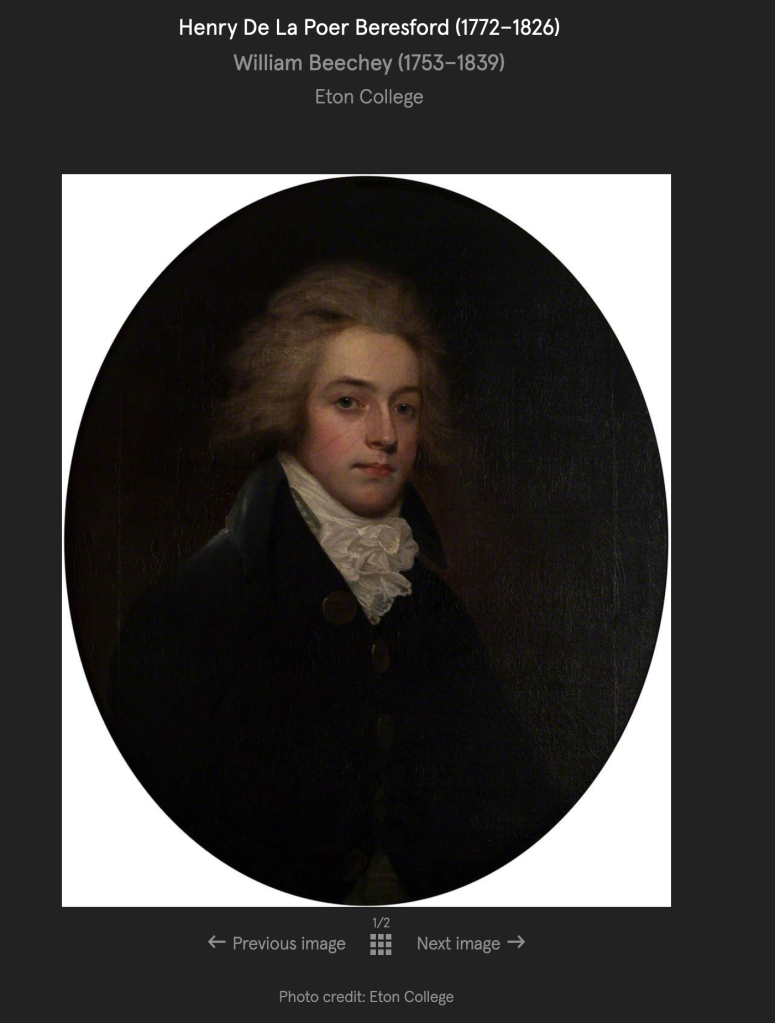

The website tells us:

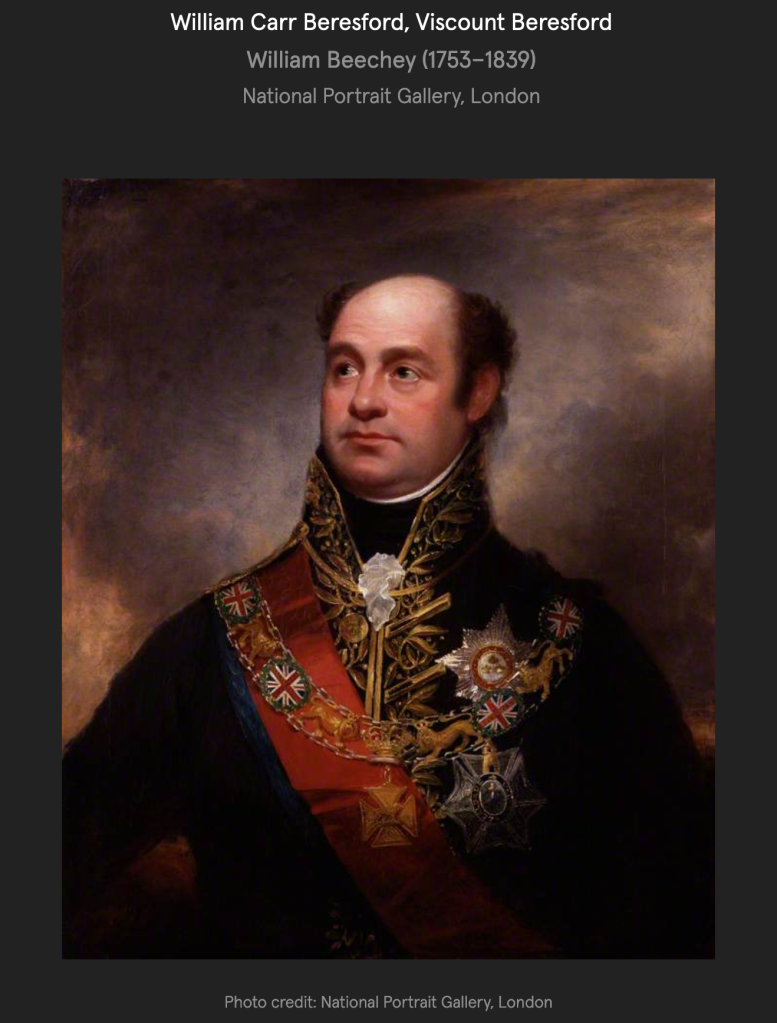

“The original house was built in the early part of the 17th century by the Fitzgerald family (a branch of the MacThomas Geraldines of the Decies).

“While in the ownership of the Uniacke family it was passed by inheritance to the Beresford family and subsequently sold by Lord William Beresford in ca 1970. The House has since been extended over the years to become an impressive six bay window residence with bright and spacious rooms overlooking this private estate with the River Tay flowing through.”

The website gives us a detailed description of the history of the house so I will quote it here:

“The house of Woodhouse as we see it at present was built in at least three stages.

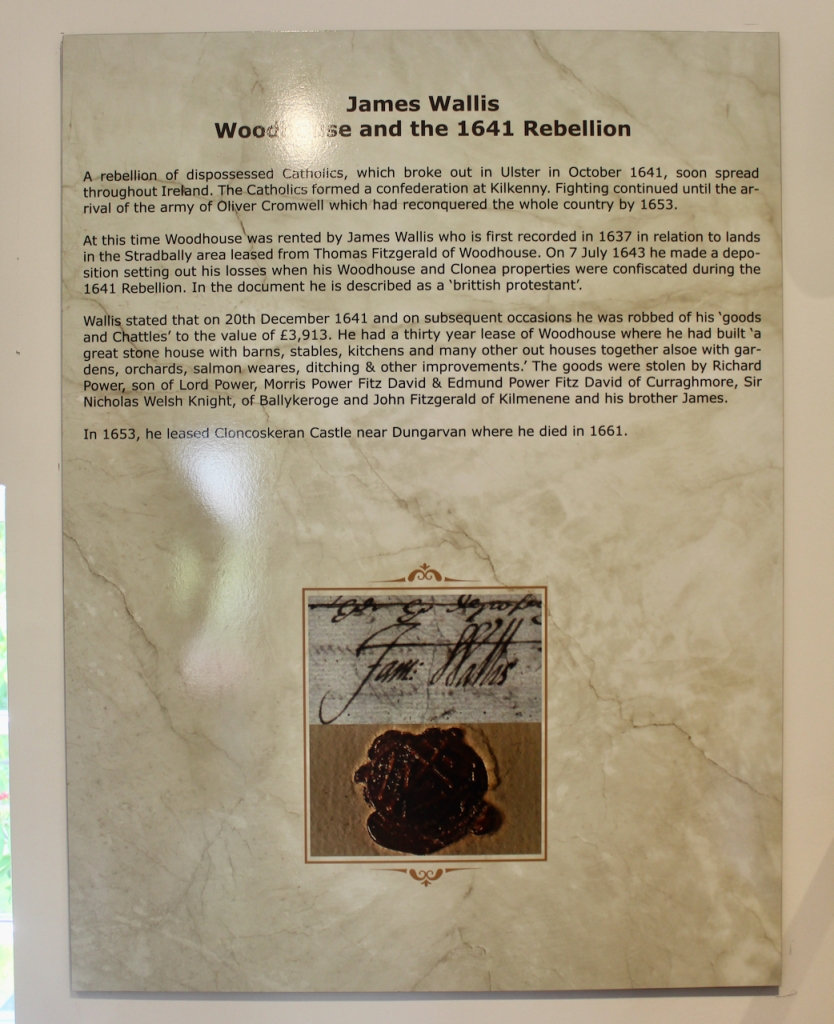

“The first one dates back to early 1600’s and the Munster Plantation, when the Messenger for Court of Wards and Liveries, an English Protestant and Undertaker (in other words Planter), James Wallis Esq., rented the lands of Woodhouse, Carrigcrokie, Stradballymore, Ballykerogue and others from the fellow Elizabethan settler and land distributor Richard Beacon. The latter gentleman was awarded the lands of the Catholic FitzGerald family in Co. Limerick and Co. Waterford (Woodhouse) by the Queen in appreciation for having performed his duties as her majesty’s attorney for the province of Munster. After leasing the land James Wallis had built a fine stone house, a mill, a walled garden accompanied by a numerous outbuildings and weirs (river dams) in the river Tay. The original house was built in an Elizabethan style on a rectangular plan.“

“During the 1641 Rebellion in Ireland, James Wallis Esq. was forced out of Woodhouse by rebels and despite his detailed Deposition made in 1642 describing the damage to his house and the loss of his goods, as well as the favourable court ruling in his favour in 1653, he never returned to the property.“

“The 1654 Civil Survey states that the owner of Woodhouse was then Thomas FitzGerald. Two generations later his grandson Major Richard MacThomas FitzGerald (then of Prospect House in Kinsalebeg, Co. Waterford) was facing large debts and had no way of paying them back so he had to sell the house and lands in 1724. Richard MacThomas Fitzgerald received over £8000 for this property but could only retain £840 while the rest was required to cover his debts.

“The new owner of Woodhouse was Richard MacThomas Fitzgerald’s distant relative and close neighbour Thomas Uniacke Esq. of Ballyvergin, Barnageehy and Youghal. It was then that the second phase of development for Woodhouse started. Thomas’ sons, Borr and Maurice Uniacke, invested heavily into renovating the dilapidated house and completely changed its character by developing it into a Georgian structure. There is no evidence to confirm who the architect of the changes was so it’s quite possible that the wealthy Uniacke family used the “Pattern Books” and hired traveling stonemasons to introduce the changes. The house was substantially enlarged and its functionality vastly changed. At this time the Woodhouse estate was is thought to have consisted of about 2500 acres in total.

“What the house looked like, may be seen at one of Borr Uniacke’s granddaughter’s amateur painting which was likely done in the first half of 1800s.“

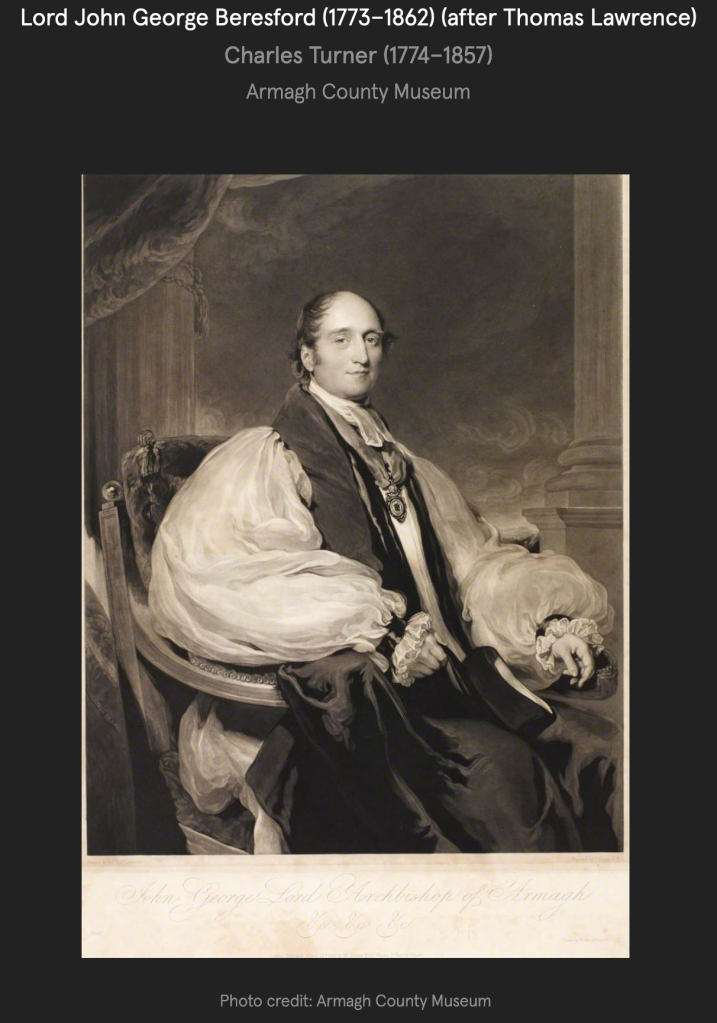

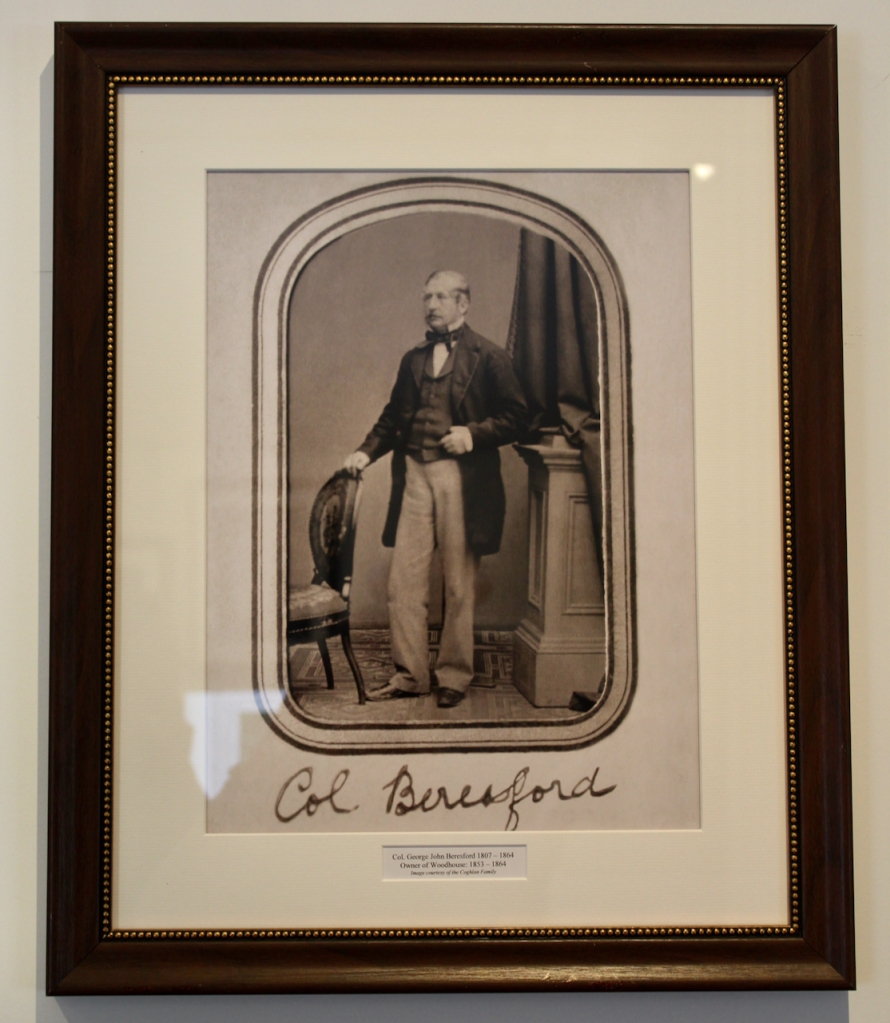

“Woodhouse remained with the Uniacke family for about 130 years but in 1853 the Estate changed hands again. It did not entirely leave the Uniacke family inasmuch as the last heiress of this branch of the family, Frances Constantia Uniacke, having inherited Woodhouse from her older brother, Robert Borr Uniacke in 1844, married George John Beresford the grandnephew of the 1st Marquess of Waterford. Frances and George John took on the responsibility for the house and had the house and the outbuildings further extended. Owing to his sufferings caused by severe gout, at the back of the main house he had built a Turkish bath. We also know that construction of the boat house in nearby Stradbally Cove (which in contemporary nautical charts was called the Blind Cove) was done at this time.“

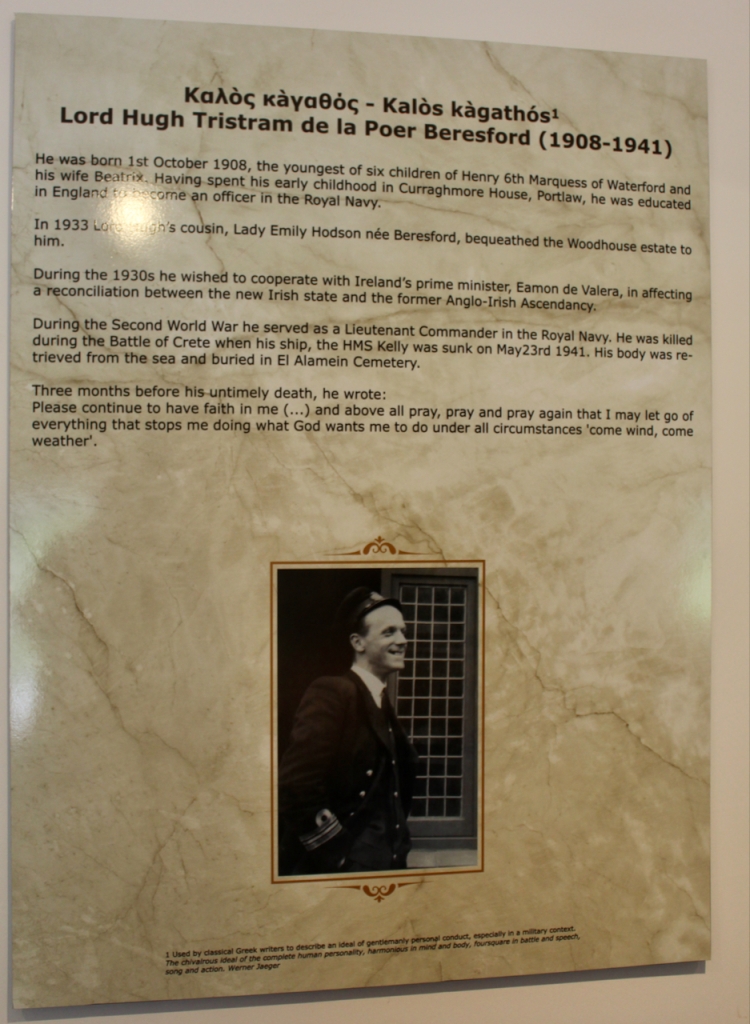

“For almost a century after that Woodhouse did not see any major changes and once again it became in need of extensive work to save it. Most of the eight Beresford children of George John and Frances Beresford married but none of them had children of their own. In 1933, the last surviving daughter of the couple, Lady Emily Frances Louisa (Beresford) Hodson bequeathed Woodhouse (the main house, 550 acres of land and the village of Stradbally) to her distant cousin Lt. Lord Hugh Tristram de la Poer Beresford Royal Navy, the sixth child of the 6th Marquess of Waterford. At the time of Lady Hodson’s death Lord Hugh was Aide De Camp to the Governor General of South Africa, yet he still managed to order renovation works including the installation of electricity and running water to the house. There is an extensive written evidence of his endeavours, which describes the works undertaken.

“In 1936 Lord Hugh Beresford made his last will and testament and bequeathed Woodhouse to his older brother Major Lord William Mostyn de la Poer Beresford. When in 1941 Lt. Cmdr. Lord Hugh Beresford was killed in action during the Battle of Crete, the will and testament were probated and when in 1944 Major Lord William Beresford returned from the war he took on Woodhouse, its lands and the village of Stradbally. Hence the third stage of structural development for Woodhouse began. Until his return however, the Estate was looked after by Arthur Hunt Esq. who had been the agent for the Beresford family since the late 1800s.

“Upon his return from the war, Lord William Beresford moved into Woodhouse. He found the Estate to be quite run down and badly in need of repairs.

“Lord William introduced considerable changes not only to the structure of the main house, but he also developed the land and garden in such a way that they yielded large crops. Every week he transported the rich surplus of vegetables, fruits and dairy products to Waterford where they were sold in the first Co-Op in town.

“Lord William and his wife Rachel are remembered as a good and kind people who successfully ran Woodhouse as a working farm and they put all their energy into making it a self-sufficient establishment.”Lord William and his wife Rachel are remembered as a good and kind people who successfully ran Woodhouse as a working farm and they put all their energy into making it a self-sufficient establishment.

“The year 1971 was the year when everything had changed for Woodhouse. It was the first time in 250 years that it was sold outside of the Fitzgerald/Uniacke/Beresford Anglo-Irish family. In that year Lord William sold the Estate to Mr. John McCoubrey who farmed and bred his cattle here and, thanks to the auspicious nature, he succeeded in that enterprise. However only one year later Mr. McCoubrey decided to move on and he, too, sold Woodhouse.

“In 1972 Mr. John Rohan bought the house and all the lands. The new owner began extensive renovations to the main house and, being the Master of the Waterford Hunt, built stables for his horses and kennels for his dogs in the walled garden. He also purchased and installed the beautiful black gate at the main entrance to the Estate.“

“Ten years later, in 1983 Woodhouse changed hands again and was purchased as an investment by a company owned by Mr. Mahmoud Fustok and his associates from the Middle East. Mr. Fustok never occupied Woodhouse but chose to make it available to Dr John O’Connell, an Irish parliamentarian, and his friends. The house was adjusted to their style, but no major renovations took place between 1983 and 2006.

“After 23 years under Mr. Fustok’s ownership Woodhouse was purchased by two Irish business partners – Mr. Aidan Farrell and Mr. Charles O’Reilly-Hyland. After their purchase these two owners sold some land parcels of Woodhouse to interested parties and made some improvements to the Estate but did not make it their residence. Eventually in 2012 they decided to sell the entire estate.“

“The new purchasers, Jim Thompson and his wife Sally, took on the task of renovating and modernizing the vastly run-down house, cottages, outbuildings and lands. Their initiative involved an enormous amount of effort and patience but ultimately was successful. The works extended into every part of the large Estate (500 acres) and was achieved over a period of six years with the support and encouragement of the people of Stradbally.“

“After many years of being forgotten and with no sufficient means to sustain itself, Woodhouse was brought back to life by various experts – architectural, building, landscape, and farm – who guided the Thompsons through the long renovation process. This commitment to bring Woodhouse back to its former glory proved very successful and as of 2019 – 400 years after the house was originally built – Woodhouse is a vibrant estate once more.“

We gathered at the ancilliary buildings for coffee and a chat before Marianna’s introduction to the house’s history. She has published a book that was for sale, along with Julian Walton.

After our talk, we visited the house and then the walled garden. The website tell us:

“When Woodhouse changed hands in 2012 a project was undertaken to bring the walled garden back to its former glory. Today the Walled Garden and Orchard have a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, herbs and many types of flowers and, thanks to Paddy Kiely and his excellent team of skilled workmen, has developed in a place of beauty in tune with nature as it was planned when originally built. An oasis of calm and tranquility situated right in the centre of the Estate, the beautifully restored Walled Garden is a perfect venue for small intimate weddings and gatherings. Completely enclosed and surrounded by high stone walls the walled garden has flowers beds, beautiful green lawns, a raised pergola overlooking the entire garden and a soothing water feature. As well as providing a beautiful backdrop for weddings the Walled Garden is also an ideal venue for a variety of special events. Whether you are looking to toast a birthday or anniversary or hold a charity event the Walled Garden adds a special atmosphere to any occasion.

For more information please get in touch 1woodhouseestate@gmail.com “

Beyond the walled garden in a further section is an orchard and greenhouse, and a house for chickens.

Whole House Rental County Waterford

1. Glenbeg House, Jacobean manor home, Glencairn, County Waterford P51 H5W0 €€€ for two, € for 7-16 – whole house rental

The website tells us: “Tranquil historic estate accommodating guests in luxury. Glenbeg, a historic castle which has been sensitively restored, preserving its historic past, whilst catering to the needs and comforts of modern living.

“Glenbeg Estate is the maternal home of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who visited during his life time and wrote some of his early work while visiting with his family here. You and your party will have exclusive use of the property during your stay.“

2. Lismore Castle, whole house rental

https://www.thehallandlismorecastle.com/lismore-castle/stay/

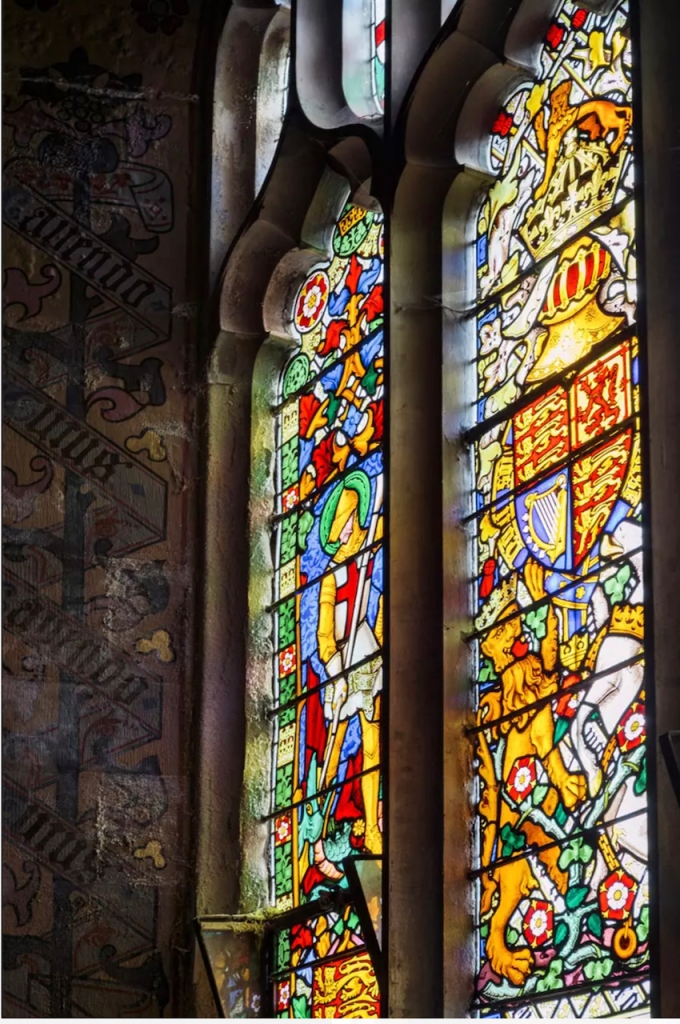

“Lismore Castle’s 800-year history is everywhere you look, from the stained-glass windows and thick stone walls, to the centuries-old gardens and the exceptional artworks by Old Masters and leading contemporary artists. Available for rent, this exclusive use castle in Ireland’s county Waterford is the perfect retreat for you and your guests.“

If anyone wants to give me a present, could you book me in for a week at Lismore Castle? See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/04/12/lismore-castle-county-waterford-whole-castle-rental-or-a-visit-to-the-gardens/

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[3] https://archiseek.com/2009/1746-bishops-palace-waterford/