www.cappoquinhouseandgardens.com

Open in 2024: Apr 8-13, 15-20, 22-27, May 1-4, 6-18, 20-25, Aug 12-31, 9am-1pm

Gardens open all year, except Sundays 9am-4pm

Fee: house/garden €15, house only €10, garden only €6

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

We visited Cappoquin House during Heritage Week in 2020. Cappoquin House was built in 1779 for Sir John Keane (1757-1829), and is still owned by the Keane family. The original house, sometimes known as “Belmont,” the name of the townland, was built on a site of an Elizabethan house built by the Munster planter, Sir Christopher Hatton. [1] It is most often attributed to a local architect, John Roberts (1712-96). [2] John Roberts was also architect of Moore Hall in County Mayo (1792 – now a ruin) and Tyrone House in County Galway (1779 – also a ruin).

Glascott Symes points out in his book Sir John Keane and Cappoquin House in time of war and revolution that it is not known who the original architect was, and it may have been Davis Ducart, who also built Kilshannig. [3]

The house was burnt and destroyed in 1923, because a descendent, John Keane (1873-1956), accepted a nomination to the Senate of the new government of Ireland. Ireland gained its independence from Britain by signing a Treaty, in which independence was given to Ireland at the expense of the six counties of Northern Ireland, which remained a part of Britain. Disagreement about the Treaty and the loss of the six counties led to the Irish Civil War. During this war, Senators’ houses were targeted by anti-Treaty forces since Senators served in the new (“pro-Treaty”) government; thirty-seven houses of Senators were burnt.

Fortunately the Keanes received compensation and engaged Richard Francis Caulfield Orpen (1863-1938) of South Frederick Street, Dublin [4], brother of painter William Orpen, to rebuild. Any material possible to salvage from the fire was used, and the fine interiors were recreated. [5] It was at this time that the former back of the house became the front, overlooking a courtyard which is entered through an archway.

The square house has six bays across with a two-bay two-storey breakfront, and the door is in a frontispiece with columns.

The house has a balustraded parapet topped with urns. The garden front, which was originally the front of the house, faces toward the Blackwater River, and has a central breakfront of three bays with round-headed windows and door. The door has cut-limestone surround with flush panelled pilasters and a fanlight. The round-headed flanking windows have fluted keystones and six-over-six timber sashed windows with fanlights.

The porch on one side of the house was built in 1913 by Page L. Dickinson for John Keane, and remains the same after the fire. [6] The work done by Dickinson inside the house in 1913, including decorative plasterwork, was destroyed.

On the east side of the house is a Conservatory.

When Sir John had the house rebuilt after the fire, he asked Page Dickinson again to be his architect but by this time Dickinson had moved to England, so Keane engaged Dickinson’s former partner, Richard Caulfield Orpen.

The white buildings around the courtyard were not destroyed in the fire and pre-date the rebuilt house. Some probably date from Hatton’s time.

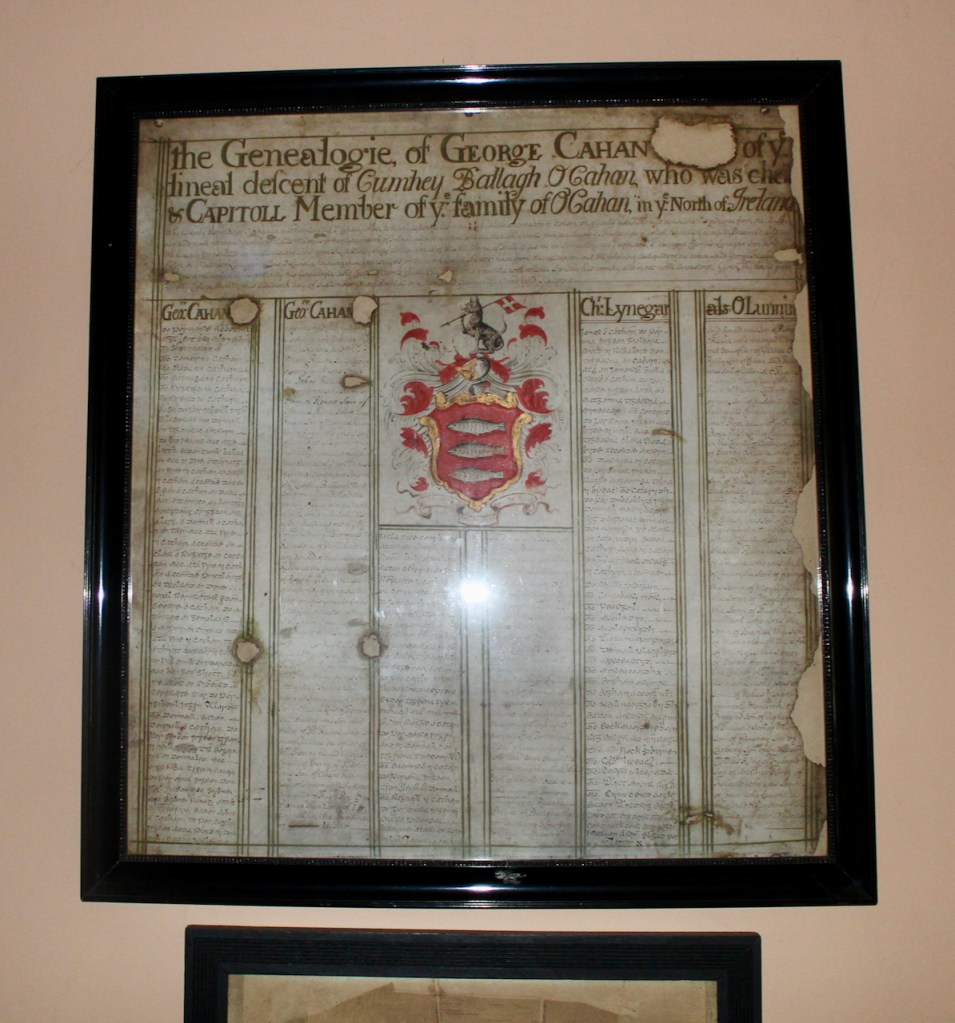

The Keanes are an old Irish family, originally named O’Cahan. The Ulster family lost their lands due to the Ulster Plantation in 1610. In 1690, following the victory of William III at the Battle of the Boyne, George O’Cahan and converted to Protestantism and anglicized his name to Keane. He practiced as a lawyer. [7] In 1738 his son, John, acquired land in the area of Cappoquin in three 999 years leases from Richard Boyle, the 4th Earl of Cork. The leases included an old Fitzgerald castle. It was this John’s grandson, also named John Keane (1757-1829), who bought out the lease and built Cappoquin House. [8]

John became MP for Bangor in the Irish parliament from 1791 to 1801 and for Youghal in the British parliament from 1801 to 1818. He was created a baronet, denominated of Belmont and Cappoquin, County Waterford, in 1801 after the Act of Union. The current owner is the 7th Baronet.

John the 1st Baronet’s oldest son, Richard, became the 2nd Baronet (1780-1855). John’s second son, John, served in the British army, and received the title of 1st Baron Keane of Ghuznee in Afghanistan and Cappoquin, Co. Waterford, in 1839. The current owner is a descendant of the elder son, Richard the 2nd Baronet, who also served in the military. He was Lieutenant Colonel of the Waterford Militia.

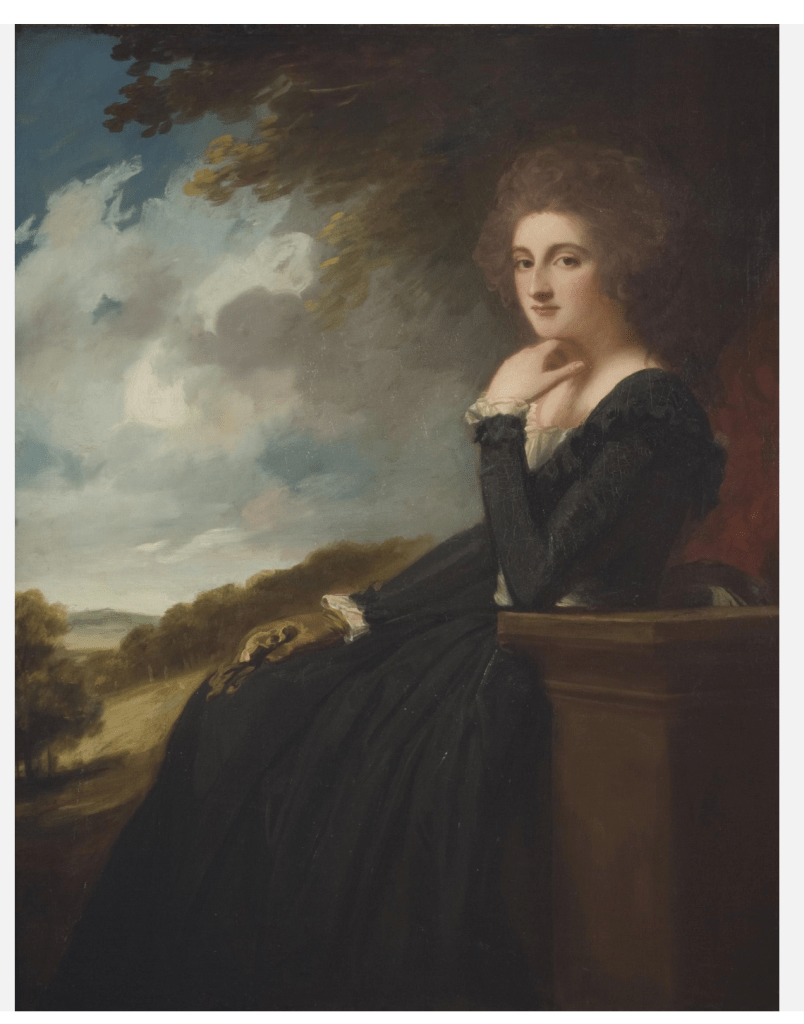

After his first wife died, Sarah Keily, daughter of Richard Keily of Springmount, County Waterford and Sarah Ussher of Cappagh House, another section 482 property in County Waterford, John Keane the 1st Baronet remarried, this time to Dorothy née Scott, widow of Philip Champion de Crespigny who was MP for Aldborough in Suffolk, England.

In 1855 the Keane estate was offered for sale in the Encumbered Estates Court, as the estate was insolvent after tenants could not pay their rents during the Famine. It seems however that the 3rd Baronet, John Henry Keane (1816-1881), managed to clear the debt and reclaim the estate.

Sir Charles showed us maps of the property, as drawn up under the Encumbered Estates Act.

The 4th Baronet, Richard Henry Keane (1845-1892), served as High Sheriff of County Waterford and Deputy Lieutenant of County Waterford. He married Adelaide Sidney Vance, whose father John was a Conservative MP for the city of Dublin, and they had several children.

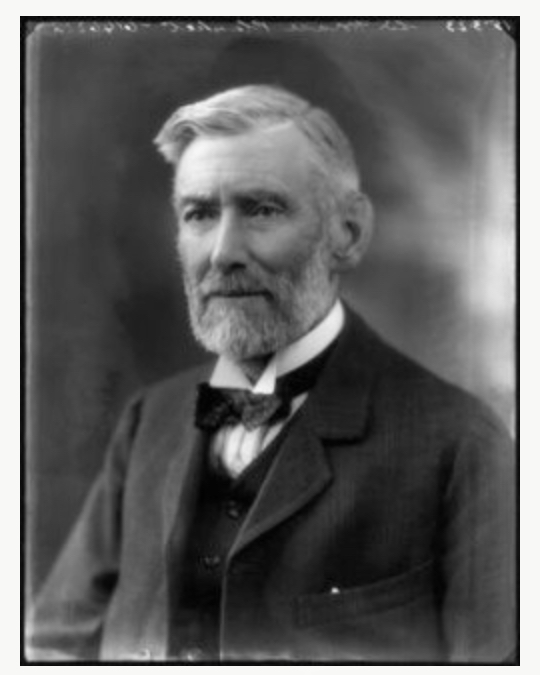

John Keane (1873-1956) the 5th Baronet also served in the British Army, and fought in the Boer War between 1899-1902. He was Private Secretary to the Governor of Ceylon between 1902 and 1905. In 1904 he was admitted to the Middle Temple to become a Barrister, but he never practiced as a Barrister. Following in his father’s footsteps he too held the office of High Sheriff of County Waterford. He followed politics closely and supported Home Rule for Ireland. He was a kind, thoughtful man and housed refugees during the wars. He fought in World War One, becoming a Lieutenant Colonel. It was this John who became a Senator.

The 5th Baronet married Eleanor Lucy Hicks-Beach, daughter of the 1st Earl of Saint Aldwyn, Gloucester, England.

Keane joined Horace Plunkett in the co-operative movement in Ireland, which promoted the organisation of farmers and producers to obtain self-reliance. The idea was that they would process their own products for the market, thus cutting out the middle man. The founders of the co-operative movement embraced new technologies for processing, such as the steam-powered cream separator. Unfortunately this led to a clash with farm labourers who unionised to prevent reduction in their wages when prices fell. Keane refused to negotiate with the Union. Rancour grew between landowners and labourers, which may have encouraged the later burning of Keane’s house. The idealism of the co-operative movement, with the goal of “better farming, better business, better living,” was easier said than done.

Keane kept diaries, which have been studied by Glascott J.R.M. Symes for an MA thesis in Maynooth University’s Historic House Studies. Symes outlines the details about the disagreements. [9] Horace Plunkett, one of the founders of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society, also became a Senator in Ireland’s first government and his house in South Dublin, Kilteragh, was also destroyed during the Civil War that followed the founding of the state.

Keane knew that his house may become a target and he sent his wife and children to live in London, and packed up principal contents of the house. Seventy six houses were destroyed in the War of Independence in what was to become the Republic of Ireland, but almost two hundred in the Civil War. [10] Unfortunately the library and some of the art collection at Cappoquin were destroyed. [11]

We entered the house through a door in the older former servants’ area in order to see the maps. We then passed into the main house, with its impressive entrance hall, with stone floor and frieze of plasterwork.

Beyond this room is the stair hall, with a top-lit cantilevered staircase and beautiful coffered dome. The timber banister terminates in a volute.

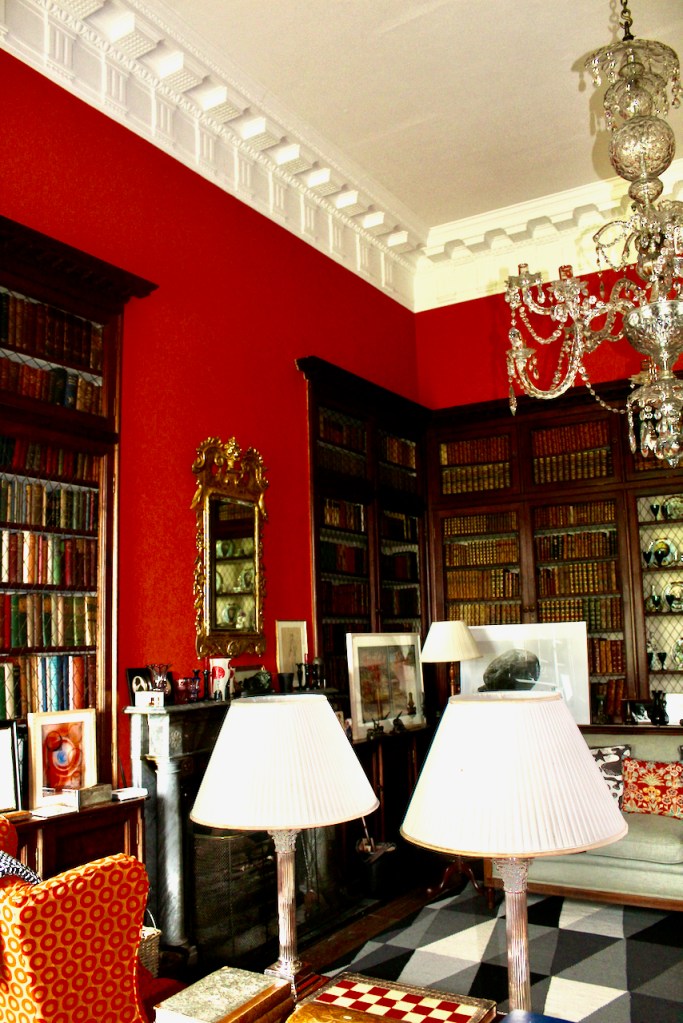

From the stair hall we entered the library, which has a dentilled cornice and built-in bookcases and is painted a deep red colour. The most intricate works in rebuilding the interior of the house were the library bookcases and the staircase, which are a tribute to the skills of carpenter James Hackett and Edward Brady, a mason from Cappoquin. [see Symes].

Beyond the stair hall is the central drawing room, which was formerly the entrance hall. It has an Ionic columnar screen, and a decorative plasterwork cornice – a frieze of ox skulls and swags.

The ceiling plasterwork and columns in the drawing room are by G. Jackson and Sons (established 1780) of London, who also made the decoration in the stair hall. Sir Charles explained to us that it would have been made not freehand but from a mould.

The chimneypiece is similar to one in 52 St. Stephen’s Green, the home of the Office of Public Works. One can tell it is old, Sir Charles told us, by running one’s hand over the top – it is not smooth, as it would be if it were machine-made. According to Symes, three original marble mantelpieces survive from before the fire, and the one in the drawing room was brought from a Dublin house of Adelaide Sidney Vance’s family, probably 18 Rutland Square (now Parnell Square), in the late nineteenth century. The Vance chimneypiece is of Carrara marble with green marble insets and carved panels of the highest quality. Christine Casey has identified the designs as derived from the Borghese vase, a vase now in the Louvre museum, which was sculpted in Athens in the 1st century BC. [12]

The chimneypieces in the dining room and former drawing room are of carved statuary marble with columns and are inset with Brocatello marble (a fine-grained yellow marble) from Siena. [13] The dining room has another splendid ceiling. The chimmeypiece in the dining room has a central panel of a wreath and oak leaves with urns above the columns.

We then went out to the conservatory.

After our house tour, we had the gardens to explore. The gardens are open to the public on certain days of the year [14]. They were laid out in the middle of the nineteenth century but there are vestiges of earlier periods in walls, gateways and streams. Sir Charles’s mother expanded the gardens and brought her expertise to the planting.

To the west of the house is an orchard of pears and Bramley apples.

One wends one’s way up the hill across picturesque lawns, the Upper Pleasure Gardens. The paths take one past weeping ash and beeches, a Montezuma pine and rhododendrons.

Our energy was flagging by the end of our walk around the gardens so unfortunately I have no pictures of the sunken garden, which is on the south side of the house, overlooking the view towards Dromana House.

I noticed that you can stay in a cottage in the courtyard! https://www.airbnb.ie/rooms/16332970?adults=2&children=0&infants=0&pets=0&wishlist_item_id=11002218087407&check_in=2023-05-23&check_out=2023-05-24&source_impression_id=p3_1681134404_prgB5ShntjT0gCzp

[1] p. 7. Symes, Glascott J.R.M. Sir John Keane and Cappoquin House in time of war and revolution. Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2016.

[3] p. 42, Symes.

[4] Irish Builder 5th March 1927, 162, https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/22810098/cappoquin-house-cappoquin-demesne-cappoquin-co-waterford

[5] p. 56. Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978). Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[6] https://theirishaesthete.com/2014/07/16/exactly-as-intended/

[7] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/search/label/County%20Waterford%20Landowners

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/03/04/risen-from-the-ashes/

[9] p. 31-35. Symes.

[10] p. 39. Symes.

[11] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-list.jsp?letter=C

[12] p. 46. Symes.

[13] p. 45. Symes.