I had so much to write about for the OPW properties in Cork that I am separating that from Counties Kerry and Waterford in Munster.

Kerry:

1. Ardfert Cathedral, County Kerry

2. The Blasket Centre, County Kerry

3. Derrynane House, County Kerry

4. Listowel Castle, County Kerry

5. Ross’s Castle, Killarney, County Kerry

6. Skellig Michael, County Kerry

Waterford:

7. Dungarvan Castle, County Waterford

8. Reginald’s Tower, County Waterford

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

Kerry:

1. Ardfert Cathedral, Tralee, County Kerry

General Information: 066 713 4711, ardfertcathedral@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/ardfert-cathedral/:

“No less a figure than St Brendan the Navigator was born in the Ardfert area in the sixth century. He founded a monastery there not long before embarking on his legendary voyage for the Island of Paradise. It was Brendan’s cult that inspired the three medieval churches that stand on the same site today.

The earliest building is the cathedral, which was begun in the twelfth century. It boasts a magnificent thirteenth-century window and a spectacular row of nine lancets in the south wall.

One of the two smaller churches is an excellent example of late Romanesque architecture. The other, Temple na Griffin, is named for a fascinating carving inside it – which depicts a griffin and a dragon conjoined.“

2. The Great Blasket Island Visitor Centre, County Kerry:

Dun Chaoin, Dingle, County Kerry

General enquiries: 066 915 6444, blascaod@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/the-blasket-centre-ionad-an-bhlascaoid/:

In Dún Chaoin, at the very tip of the Dingle Peninsula, is an utterly unique heritage centre and museum. A stunning piece of architecture in itself, the Blasket Centre tells the story of the Blasket Islands and the tiny but tenacious Irish speaking community who lived there until the mid-20th century.

Life on the Blaskets was tough. People survived by fishing and farming and every day involved a struggle against the elements. Emigration and decline led to the final evacuation of this extraordinary island in 1953.

The island population has left a massive cultural footprint. They documented the life of their community in a series of books which are invaluable social records and classics of Irish literature. They are both a window into the past and a fascinating resource for today.

Visit Ionad an Bhlascaoid – the Blasket Centre – to experience the extraordinary legacy of the Blasket Islanders and delve into the heart of Irish culture, language and history.” [3]

The website has lots more information for you to learn about life on the Islands. The Great Blasket was inhabited continuously for at least 300 years. It has Ireland’s largest colony of grey seals also. During the famine, there was not a single death recorded from hunger, as fishing sustained the islanders. At its peak the population reached 160, but declined due to emigration. Two of the houses have been restored by the OPW. The visitor centre is on the mainland but one can take a privately operated passenger boat to the Island, weather permitting.

3. Derrynane House, Caherdaniel, County Kerry:

General enquiries: 066 947 5113, derrynanehouse@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/derrynane-house/:

“At the southern tip of the Iveragh Peninsula is Derrynane House, the ancestral home of one of the greatest figures of Irish history. Daniel O’Connell, known as ‘The Liberator’, was a lawyer, politician and statesman. The demesne landscape is now included in Derrynane National Historic Park – over 120 hectares of lands rich in natural and cultural heritage with a plethora of archaeological, horticultural, botanical and ecological treasures.

Derrynane was the home of the O’Connell family for generations. The young Daniel was raised there and returned almost every summer for the rest of his life.

The house now displays many unique relics of O’Connell’s life, including a triumphal chariot presented to him by the citizens of Dublin in 1844 and the very bed in which he passed away three years later.”

Derrynane comes from the Irish meaning “the oak wood of St Fionan,” Doire Fhionan. [4] Throughout Daniel O’Connell’s career, Derrynane was his country residence and the place where he and his family spent most of their summers. He inherited the house in 1825. He wrote in 1829:

“This is the wildest and most stupendous scenery of nature – and I enjoy residence here with the most exquisite relish…I am in truth fascinated by this spot: and did not my duty call me elsewhere, I should bury myself alive here.” [see 4]

Mark Bence-Jones writes about the house:

“The house, which is believed to have been first late-roofed house in this remote and mountainous part of the country, originally consisted of two unpretentious ranges at right angles to each other, probably built at various times between ca 1700 and 1745 and somewhat altered in later years; one range being of two storeys and the other mainly of two storeys and a dormered attic, which in second half of C18, became a third storey. Between 1745 and 1825 a wing was built at what was then the back of the house, this side towards Derrynane Bay; and in 1825 the great Daniel O’Connell extended this wing in the same unpretentious style with rather narrow sash windows; so that what had previously been the back of the house became the front, with reception rooms facing the sea. O’Connell also built a square two storey block with Irish battlements at right angles to his main addition, forming at attractive three sided entrance court, the other two sides being 1745-1825 wing and one of the original ranges. The battlemented block is weather-slated, as indeed all O’Connell’s additions were originally; he also weather slated some of the older parts of the house. Finally, in 1844, O’Connell built a new chapel in thanksgiving for his release from prison. It flanks the entrance court on the side furthest from the sea and is Gothic; based on the chapel in the ruined medieval monastery on Abbey Island nearby; it was designed by O’Connell’s third son, John O’Connell, MP. The interior of the house is simple, and the ceilings are fairly low. The two principal reception rooms are the drawing-room and dining-room which are one above the other in 1825 wing; they have plain cornices; the dining room has a Victorian oak chimneypiece, the drawing room an early C19 Doric chimneypiece of white marble. The benches and communion rail of the chapel are of charmingly rustic Gothic openwork. The house is now owned by the Commissioners of Public Works, who demolished one of the original ranges 1965 [due to poor structural condition]. The rest of the structure has been restored and is open to the public, the principal rooms containing O’Connell family portraits and objects related to Daniel O’Connell’s life and career.” [5]

The O’Connell family gave the house to the Derrynane Trust in 1946. Despite earlier warnings that it would not be responsible for O’Connell’s ancestral home, in late 1964 the government agreed to acquire Derrynane House from the Derrynane Trust. David Hicks writes a good summary about Daniel O’Connell:

“In the 18th and 19th centuries there was a series of restrictions placed on Catholics in Ireland – the Penal Laws – which curtailed them in many avenues of life. These restrictions extended to property ownership and education, and Catholics were also barred from holding political office. As a man of the law, O’Connell became an advocate for the abolition of the last vestiges of the Penal Laws and in 1823 brought the Catholic Church into Irish politics. He used his network of acquaintances to mobilise the people to campaign for Catholic emancipation from discrimination and to gain political rights for Catholics. Collections were taken and no matter how small the donation it was for a great cause. This led to the unification of Catholics in Ireland. In 1828, O’Connell stood for the British Parliament, the first Catholic to do so in over 100 years, and won his seat easily. While he had his supporters in the British cabinet, others such as the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel opposed Catholic emancipation. They were aware, however, that not allowing O’Connell to take his parliamentary seat would result in possible rebellion in Ireland. Another probelm arose: in order for O’Connell to take his seat in Parliament, he would have to take an Oath of Supremacy which recognised the British monarch as head of the Church and state. As the Pope in Rome is head of the Catholic church, O’Connell could not and would not swear allegiance to a British monarch as head of the Church of England. Wellington and Peel convinced the King to allow the emancipation of Catholics to prevent a possible uprising of the large Catholic population in Ireland. As a result Catholics gained political rights under the Emancipation Act of 1829 and could enter Parliament without taking the oath. O’Connell had to be re-elected before he could take his seat as the Act could not be implemented retrospectively. He was finally elected in 1829 to the British Parliament and became known as the Liberator, a moniker which is still associated with his legend.

By 1837 O’Connell had grown frustrated at how little he could achieve in Ireland in a British Parliament. He now launched a new campaign: to repeal the Act of Union between Ireland and Britain. While he did not want Ireland to leave the Empire, he did want her to have her own parliament where Catholics could exercise their own political power and ambitions. Initially, this campaign garnered a lot of support. In the 1840s, O’Connell held large meetings to campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union. These meetings were usually held in a large field, racecourse or fairground and opened with a huge procession of bands in uniform, floats, carriages and carts, with thousands of local residents on foot or horseback. Crowds gathered around a makeshift platform, on which O’Connell stood to address them. One of his largest political rallies was held at the provocative spot of the Hill of Tara, site of the residence of the former high kings of Ireland, intended to inspire the attending crowd of half a million people.

The size of this rally was relayed to the British Parliament and within three months O’Connell was charged with conspiracy, creating discontent and disaffection, for which he was arrested and jailed. When he was released from prison he made his way through the crowded streets of Dublin on a specially made chariot which still survives at Derrynane.” [6]

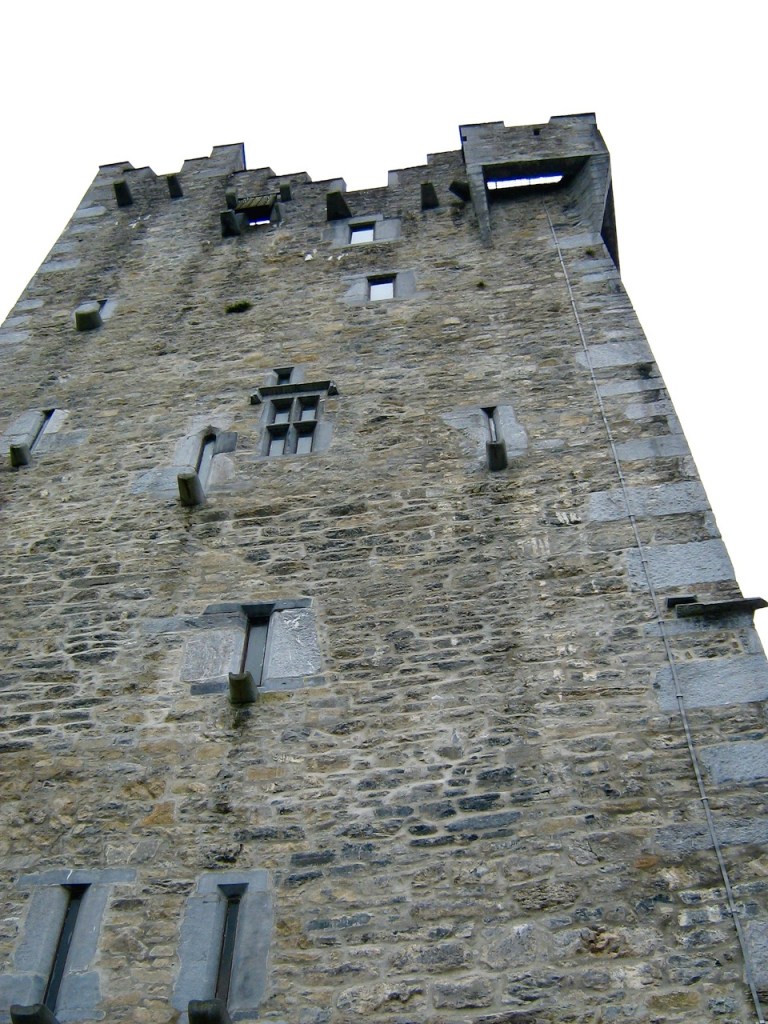

4. Listowel Castle, County Kerry:

General information: 086 385 7201, padraig.oruairc@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/listowel-castle/:

“Listowel Castle stands on an elevation overlooking the River Feale, above the location of a strategic ford. Although only half of the building survives, it is still one of Kerry’s best examples of Anglo-Norman architecture.

Only two of the original four square towers, standing over 15 metres high, remain. The towers are united by a curtain wall of the same height and linked together – unusually – by an arch on one side.

Listowel was the last bastion [of the Fitzgeralds] against the forces of Queen Elizabeth in the First Desmond Rebellion in 1569. The castle’s garrison held out for 28 days of siege before finally being overpowered by Sir Charles Wilmot. In the days following the castle’s fall, Wilmot executed all of the soldiers left inside.“

5. Ross Castle, Killarney, County Kerry:

General Enquiries: 064 6635851, rosscastle@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/ross-castle/:

“Ross Castle perches in an inlet of Lough Leane. It is likely that the Irish chieftain O’Donoghue Mór built it in the fifteenth century.

Legend has it that O’Donoghue still slumbers under the waters of the lake. Every seven years, on the first morning of May, he rises on his magnificent white horse. If you manage to catch a glimpse of him you will enjoy good fortune for the rest of your life.

Ross Castle was the last place in Munster to hold out against Cromwell. Its defenders, then led by Lord Muskerry, took confidence from a prophecy holding that the castle could only be taken by a ship. Knowing of the prophecy, the Cromwellian commander, General Ludlow, launched a large boat on the lake. When the defenders saw it, this hastened the surrender – and the prophecy was fulfilled [in 1652].“

The Castle came into the hands of the Brownes who became the Earls of Kenmare and owned an extensive portion of the lands that are now part of Killarney National Park. It was leased to Valentine Browne (d. 1589), ancestor of the Earls of Kenmare, who was involved with the Plantation of Munster, surveying the land. He served as MP for County Sligo in the Irish Parliament in 1585/6. The Brownes obtained ownership of the castle and lands when it could be proven that they did not play a part in the Confederate Rebellions between 1641-1653. However, Valentine Browne (1639-1694) 1st Viscount of Kenmare (and 3rd Baronet Browne of Mohaliffe, County Kerry) was loyal to James II had to forfeit his estate. The title Earl of Kenmare comes originally from Kenmare Castle in County Limerick. His grandson, 3rd Viscount, recovered the estates, but could not get possession of Ross Castle, which had been taken over as a military barracks, so around 1726 he built a new house a little way to the north of the castle, closer to the town of Killarney, Kenmare House, which has been demolished when a later house was built.

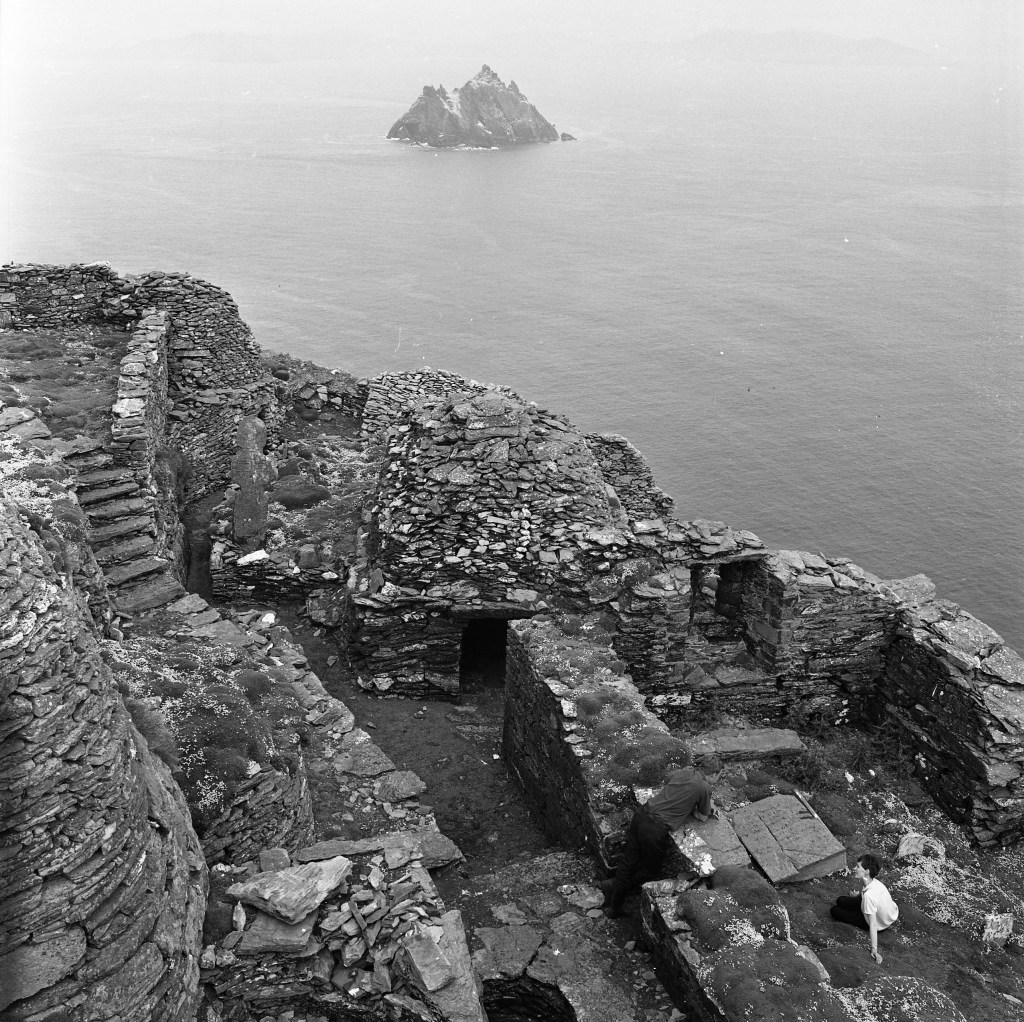

6. Skellig Michael, County Kerry:

General Information: opwskellig@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/skellig-michael/:

“The magnificent Skellig Michael is one of only two UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Republic of Ireland.

On the summit of this awe-inspiring rock off the Kerry coast is St Fionan’s monastery, one of the earliest foundations in the country. The monks who lived there prayed and slept in beehive-shaped huts made of stone, many of which remain to this day.

The monks left the island in the thirteenth century. It became a place of pilgrimage and, during the time of the Penal Laws, a haven for Catholics.

Following in the monks’ footsteps involves climbing 618 steep, uneven steps. Getting to the top is quite a challenge, but well worth the effort.

As well as the wealth of history, there is a fantastic profusion of bird life on and around the island. Little Skellig is the second-largest gannet colony in the world.“

Waterford:

7. Dungarvan Castle, County Waterford:

General Information: 058 48144.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/dungarvan-castle/:

“This castle dates from the early days of the Anglo-Norman settlement in Ireland. It was built c.1209 to safeguard the entrance to Dungarvan Harbour. The polygonal shell keep – a rare building type in Ireland – is the earliest structure on the site.

The castle has an enclosing curtain wall, a corner tower and a gate tower. Within the wall is a two-storey military barracks, which dates from the first half of the eighteenth century. It was used by the British Army and the Royal Irish Constabulary until 1922. During the Irish Civil War Dungarvan Castle was destroyed by the Anti-Treaty IRA. It was subsequently refurbished and served as the Headquarters of the local Garda Síochana.

Today the Barracks and Castle grounds are open to visitors. Inside you will find a revealing exhibition on the Castle’s long and intriguing history.“

8. Reginald’s Tower, The Quay, Waterford, County Waterford:

General information: 051 304220, reginaldstower@opw.ie

https://www.waterfordtreasures.com/reginalds-tower

Reginald’s Tower is named after the Viking who founded Waterford in 1914 and is home now to Viking treasures.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/reginalds-tower/:

“Once described as ‘a massive hinge of stone connecting the two outstretched wings of the city’ this tower has never fallen into ruin and has been in continuous use for over 800 years.

Originally the site of a wooden Viking fort, the stone tower we see today actually owes its existence to the Anglo-Normans who made it the strongest point of the medieval defensive walls. Later it was utilised as a mint under King John, before serving various functions under many English monarchs. Weapons, gunpowder and cannons have all been stored here reflecting various periods of Waterford’s turbulent history.

Take the spiral stairs up and en route see the remains of a 19th century prison cell, artefacts from Waterford’s Viking history, and the sword of the Chief Constable whose family were the last residents of the tower.

On two floors are housed one branch of the Waterford Museum of Treasures, concentrating on the town’s thrilling Viking heritage.“

[1] https://repository.dri.ie/

[2] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[3] see the website https://blasket.ie/

[4] p. 120. Living Legacies: Ireland’s National Historic Properties in the care of the OPW, Government Publications, Dublin, 2018.

[5] p. 102. Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[6] p. 107-119, Hicks, David. Irish Country Houses, Portraits and Painters. The Collins Press, Cork, 2014.