On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

I’m working on write-ups at the moment so am updating this entry for County Limerick, after we visited during Heritage Week last year. We’ll be visiting Limerick again later in the year to see the Old Rectory in Rathkeale, and hopefully Odellville and Kilpeacon. Last year we stayed in Ash Hill and I highly recommend it!

Limerick is in the province of Munster. Other Munster counties are Clare, Cork, Kerry, Tipperary and Waterford.

For places to stay, I have made a rough estimate of prices at time of writing (2021):

€ = up to approximately €150 per night for two people sharing (in yellow on map);

€€ – up to approx €250 per night for two;

€€€ – over €250 per night for two.

For a full listing of accommodation in big houses in Ireland, see my accommodation page: https://irishhistorichouses.com/accommodation/

Limerick:

1. Askeaton Castle, County Limerick – OPW

2. Desmond Castle, Adare, County Limerick – OPW

3. Desmond Castle, Newcastlewest, County Limerick – OPW

4. Glebe House, Holycross, Bruff, Co. Limerick – section 482

5. Glenville House, Glenville, Ardagh, Co. Limerick – section 482

6. Glenquin Castle, Newcastle West, Co Limerick – open to visitors

7. Glenstal Abbey, County Limerick

8. Kilpeacon House, Crecora, Co. Limerick – section 482

9. King John’s Castle, Limerick

10. Odellville House, Ballingarry, Co. Limerick – section 482

11. Mount Trenchard House and Garden, Foynes, Co. Limerick – section 482

12. The Turret, Ryanes, Ballyingarry, Co. Limerick – section 482

13. The Old Rectory, Rathkeale, Co. Limerick – section 482

Places to stay, County Limerick:

1. Adare Manor, Limerick – hotel €€€

2. Ash Hill Towers, Kilmallock, Co Limerick – section 482, Hidden Ireland accommodation €

3. Ballyteigue House, County Limerick self-catering whole house accommodation, rental per week. €€ for two, € for 4-10

4. Deebert House, Kilmallock, County Limerick – B&B and self-catering

5. The Dunraven, Adare, Co Limerick €

Whole house rental County Limerick

1. Ballyteigue House, Bruree, County Limerick – self-catering whole house accommodation, rental per week. €€ for two, € for 4-10

2. Fanningstown Castle, Adare, County Limerick – sleeps 10

3. Flemingstown House, Kilmallock, Co. Limerick, Ireland whole house accommodation, up to 11 guests. €€€ for two for a week, € for 4-11

4. Glin Castle, whole house rental.

5. Springfield Castle, Drumcollogher, Co. Limerick, Ireland €€€ for 2, € for 5-25.

2025 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2025 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

Limerick:

1. Askeaton Castle, County Limerick – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/06/26/opw-sites-in-munster-clare-limerick-and-tipperary/

2. Desmond Castle, Adare, County Limerick – OPW

See my OPW write-up:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/06/26/opw-sites-in-munster-clare-limerick-and-tipperary/

3. Desmond Castle, Newcastlewest, County Limerick – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/06/26/opw-sites-in-munster-clare-limerick-and-tipperary/

4. Glebe House, Holycross, Bruff, Co. Limerick – section 482

Open dates in 2024: Jan 4-5, 8-12, 15-19, 22-26, 29-31, June 10-14, Aug 17-25, Sept 2-27, Mon-Fri, 2pm-6pm, Sat-Sun, 8am-12 noon

Fee: Free

5. Glenville House, Glenville, Ardagh, Co. Limerick V42 X225 – section 482

Open dates in 2023: Apr 2-30, May 1-31, June 1-12, Tue-Sat, Aug 17-25, 9.30am-1.30pm

Fee: adult €5, OAP/student €3, child free

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/03/19/glenville-house-glenville-ardagh-co-limerick-v42-x225/

6. Glenquin Castle, Newcastle West, Co Limerick – open to visitors

One of the finest tower houses to survive from the 16th century, Gleann an Choim (Glen of the Shelter) is situated a few miles from Ashford at the edge of the road (open to the public during summer).

This castle was a fortified dwelling, for the protection against raids and invaders, more correctly described as a Tower House. [5]

Robert O’Byrne tells us: “Thought to stand on the site of an older building dating from the 10th century, Glenquin Castle in Killeedy was built by the O’Hallinan family (their name deriving from the Irish Ó hAilgheanáin, meaning mild or noble). When the castle was built seems unclear; both the mid-15th and mid-16th centuries are proposed. Regardless, it is typical of tower houses being constructed at the time right around the country.” [6]

7. Glenstal Abbey, County Limerick

The website tells us: “Glenstal Abbey is home to a community of Benedictine monks in County Limerick, Ireland, and is a place of prayer, work, education and hospitality. The monastery sits alongside a popular guesthouse and a boarding school for boys, housed within a 19th century Normanesque castle amidst five hundred magnificent acres of farmland, forest, lakes and streams.

“We are happy to welcome groups who wish to visit the monastery and spend some time getting to know our place, our tradition and our life.”

You can book to stay, as a retreat: https://glenstal.com/abbey/stay/

The castle was built as a home for Joseph Barrington (1764-1846), 1st Baronet of Limerick. Joseph married Mary Baggott – I wonder are we distantly related? She was the daughter of Daniel Baggot (the landed families website tells us that he was a bootseller in Limerick!). Joseph’s son Matthew (1788-1861), 2nd Baronet was also involved with having the home built.

The front door is flanked by figures of Henry II and Queen Eleanor, who were such a warring couple that one wonders if they were chosen in ignorance: the Queen holds a scroll on which is inscribed the Irish welcome, Cead mile failte. [9]

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that in 1830 Joseph Barrington 1st Baronet built Barrington’s Quay on the north bank of the Shannon, and (with others) initiated land reclamation and the construction of embankments to allow the city of Limerick to expand along the river.

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

p. 139. “(Barrington, BT/Pb) A massive Norman-Revival castle by William Bardwell, of London, begun in 1837, though not finished till about 1880.

“The main building comprises a square, three-storey keep joined to a broad round tower by a lower range.

“The entrance front is approached through a gatehouse copied from that of Rockingham Castle, Northamptonshire. The stonework is of excellent quality and there is wealth of carving; the entrance door is flanked by the figures of Edward I and Eleanor of Castille; while the look-out tower is manned by a stone soldier. Groined entrance hall; staircase of dark oak carved with animals, foliage and Celtic motifs, hemmed in by Romanesque columns; drawing room with mirror in Norman frame. Octagonal library at the base of the round tower, lit by small windows in very deep recesses; the vaulted ceiling painted with blue and gold stars; central pier panelled in looking-glass with fireplace. Elaborately carved stone Celtic-Romanesque doorway copied from Killaloe Cathedral between two of the reception rooms. Glen with fine trees and shrubs; river and lake, many-arched bridge. Now a Benedictine Abbey and a well-known boys’ public school.”

Sean O’Reilly writes: “the castle remains one of the most magnificent attempts at creating an Irish version of the medieval Anglo-Norman castle. Yet Glenstal’s castle-like form is not due to the need for defence. In a tradition going back to Georgian castles such as Glin, Co Limerick and Charleville forest, Co Offaly, the intention is to evoke some ancient time, but combined with the needs of a modern country house.” [10]

“(p. 172)The appearance of antiquity might also give to its patron at least the suggestion of an ancient lineage, and that in itself, in an increasingly disjointed Irish society, was not without significance. The Barringtons settled in Limerick relatively late, at the end of the seventeenth century, and furthered their fame less though marriage than through hard work, innovative industry and successful trading. Pofessional advancement was not accompanied by significant social advance, and though Joseph Barrington was a baronet, the family were in essence business people rather than aristocracy. Although there was no speedier way of securing the impression of title and history than by having one’s own castle, his son Matthew, Crown solicitor for Munster, must have recognized the discomfort of real castles, and so decided to build a more comfortable, modern version.

“The design passed through numerous phases even before building began. Even after construction commenced in 1838, from designs provided by the successful English architect William Bardwell, changes, indecision and economic variables all added further complications. Initially, before the selection of the design, the problem was the choice of site. Not having inherited lands on which to build, Barrington might use any site, and he decided first on property he had leased in 1818 from the increasingly encumbered Limerick estates of the Lord Carberry. Part of these included the district of Glenstal, at one time intended as a site for the house, and although Barrington later turned to various other sites, he took with him the name. Consequently, in a very characteristic Georgian incongruity, the title of this apparently ancient castle bears no relation to the land on which it sits.“

O’Reilly tells us “[William] Bardwell [1795-1890], little known today despite his long life – he died in 1890 aged 95 – was still less familiar when first employed by Barrington, and Glenstal remains his most important work. After training in England he advanced his studies, rather unusually for the date, in France. He gained some celebrity through competing both for the London Houses of Parliament, and for the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge. It may well have been the Norman tower proposed by Bardwell as his entrance to Parliament that suggested him to his Limerick patron, though as all periods of architecture were intended to be represented in that building, any prospective client may have found something of interest.“

“The ultimate inspiration for Bardwell’s Glenstal lay less with the designs of the Paines or O’Hara than with the work of Thomas Hopper, notably his Gosford Castle in Armagh, of 1819. This was the first Normal revival castle in these islands, and the first in a style that Hopper would make his own. Neither Barrington nor Bardwell need have been with Gosford itself, for by the late 1830s the type was not uncommon.

“…Bardwell was in Ireland in 1840, reviewing the completed work. It then extended from the largest, southern, tower to the gatehouse in the south-east wall. However, work stopped in the following year, and began again only in 1846 or 1847. Construction paused again in 1849, to recommence in about 1853, with Bardwell finally paid off, and a Cork architect, Joshua Hargrave, appointed to complete the work with restricted funds, and to create something approaching a functioning building…“

“Most carving was executed by an English firm, W.T. Kelsey of Brompton, which provided fifteen cases of columns, capitals and corbels in 1844. However, the detailing of much of the carved work suggests some familiarity with Irish early Christian sources, and echoes abound of recent work at Adare Manor, itself being slowly built over many years, although using native craftsmen.“

“If much of the carved detail is evocative rather than accurate, there are also striking and significant copies of Irish early Christian design. The style was then only beginning to receive proper attention as part of Ireland’s heritage. The idea may have been inspired again by Dunraven’s Adare – Barrington is known to have had business dealings with the family – for they used such Hiberno-Romanesque designs in the doorcase of their entrance hall. At Glenstal we find superb copies, notably the doorcase connecting the dining room and drawing room. This is a magnificently carved and surprisingly accurate reconstruction of the doorway in Killaloe Cathedral, Co Clare, today recognized as one of the masterpieces of the Irish Romanesque. A lack of understanding of the importance of such work was prevalent in mid-nineteenth-century Ireland – it might be compared to the recent lack of interest in the heritage of the country house – and its introduction here was an important moment in the history of the revival of interest in Ireland’s Christian and Celtic legacy.“

“…It was part of a wider interest in Ireland’s national character that the future of this important house was put in jeopardy. The tragic accidental shooting of the daughter of the 5th Baronet, Charles Barrington, by the IRA in an ambush on the Black and Tans in May 1921, led to the family’s departure and, eventually, the sale of the estate in 1925.“

Timothy William Ferres quotes “The Origins and Early Days of Glenstal” by Mark Tierney OSB, in Martin Browne OSB and Colmán O Clabaigh (eds), The Irish Benedictines: a history (Dublin, 2005):

“When eventually, in 1925, the time came to leave, Sir Charles made a magnificent gesture. He wrote to the Irish Free State government, offering Glenstal as a gift to the Irish nation, specifically suggesting that it might be a suitable residence for the Governor-General.

“Mr W T. Cosgrave, the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, and Mr Tim Healy, the Governor-General, visited Glenstal in July 1925, and ‘were astonished at its magnificence, which far exceeded our expectations’. However, financial restraints forced them to turn down the offer. Mr Cosgrave wrote to Sir Charles, stating that ‘our present economic position would not warrant the Ministry in applying to the Dail to vote the necessary funds for the upkeep of Glenstal’. “

8. Kilpeacon House, Crecora, Co. Limerick – section 482

Open dates in 2024: May 1-June 30, Mon-Sat, Aug 17-25, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult/child/OAP €8

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

“[Gavin, sub Westropp/IFR] An early C19 villa undoubtedly by Sir Richard Morrison, though it is undocumented; having a strong likeness to Morrison’s “show” villa, Bearforest, Co Cork; while its plan is, in Mr. McPartland’s words, “an ingenious contraction of that of Castlegar,” one of his larger houses in the villa manner, 2 storey; 3 bay front; central breakfront; curved balustraded porch with Ionic columns; Wyatt windows under semi-circular relieving arches on either side in lower storey. Eaved roof. 5 bay side elevation. Oval entrance hall. Small but impressively high central staircase hall lit by lantern and surrounded by arches lighting a barrel-vaulted bedroom corridor. The seat of the Gavin family.“

The landed estates database tells us:

“Lewis writes that the manor was granted to William King in the reign of James I and that “the late proprietor” had erected a handsome mansion which was now the “property and residence of Cripps Villiers”. In his will dated 1704 William King refers to his niece Mary Villiers. The Ordnance Survey Field Name Book states that Kilpeacon House was the property of Edward Villiers, Dublin, and was occupied by Miss Deborah Cripps. Built in 1820 it was a large, commodious building of 2 stories. It was the residence of Edward C. Villiers at the time of Griffith’s Valuation, held in fee and valued at £60. Bought by Major George Gavin in the early 1850s from the Villiers and the residence of his son Montiford W. Gavin in the early 20th century. The Irish Tourist Association surveyor writes in 1942 that this house was completed in 1799. The owner was Mrs O’Kelly, her husband having purchased the house in 1927 from the Gavins. This house is still extant and occupied.” [11]

9. King John’s Castle, Limerick

Maintained by Shannon Heritage. Archiseek tells us: “King John’s Castle, on the south side of Thomond Bridge head, built in 1210 “to dominate the bridge and watch towards Thomond”, is one of the finest specimens of fortified Norman architecture in Ireland.

“The castle is roughly square on plan and its 60 meter frontage along the river is flanked by two massive round towers, each over 15m. in diameter with walls 3 metres thick. The castle gate entrance – a tall, narrow gateway between two tall, round towers is quite imposing. There is another massive round tower at the north east corner of the fortification, but the east wall and the square tower defending the south-east corner of the castle, and on which cannons were mounted, is long demolished.

“There was a military barracks erected within the walls in 1751, some of which still remains. Houses were also erected in the castle yard at a very much later date. These have now been removed and a modern visitor centre built on the walls.

The walls and towers still remaining of the castle are in reasonably good state of preservation. The domestic buildings of the courtyard do not survive, except for remnants of a 13th century hall and the site of what could be the castle chapel.” [12]

“The castle was built around 1197 under the orders of King John following the invasion of the Anglo-Normans. It was built on the site of an original Viking settlement believed to date back to 922 AD.” [13]

The information board tells us that built between 1210-1212 along part of the line of the 12th century ringwork, the gatehouse was the first of its kind to be constructed in Ireland, with boldly projecting towers placed on either side of the gate. It followed the latest trend in European castle building, moving from rectangular to round towers, as curved walls offered better protection from attack, particularly from mining. Mining is when one digs a series of holes or “mines” under the walls in order to weaken the walls – hence comes our term “to undermine.” The two towers of the gatehouse are “D” shaped in plan, with three floors of circular chambers within and a parapet on top.

By flanking the gate, the two towers allowed the castle’s entrance to be defended in depth, from a number of well-positioned arrow loops in the chambers. The defenses also included a portcullis and a murder hole. The castle was also supplied via the river, where there is a more modest watergate in the west curtain wall.

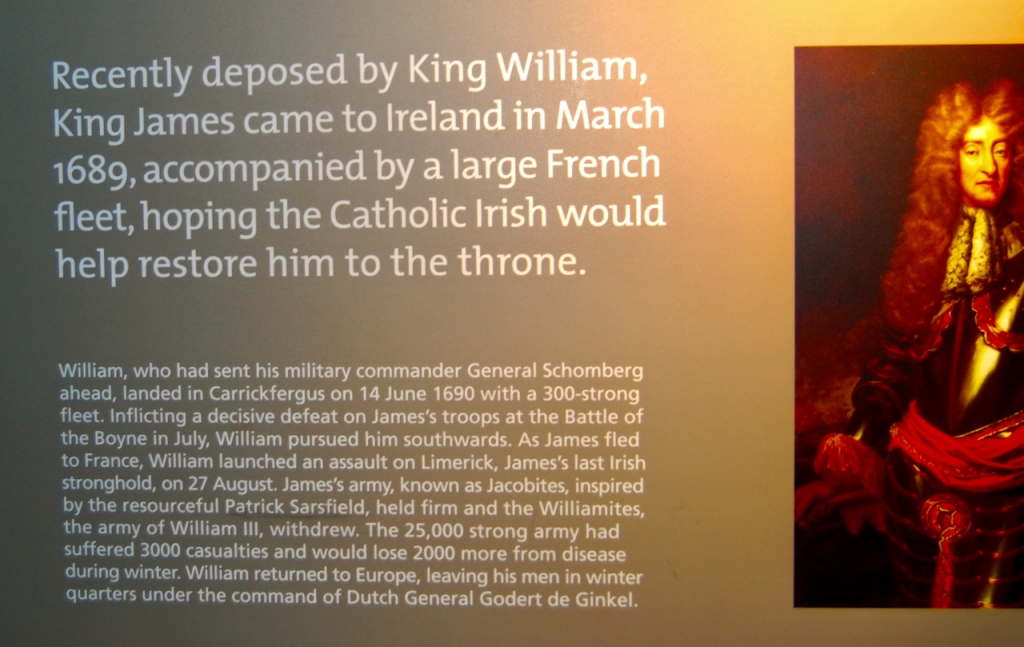

“In 1642 the castle was occupied by people escaping the confederate wars and was badly damaged in the Siege of Limerick. The confederate leader Garret Barry had no artillery so dug under the foundations of the castle’s walls, causing them to collapse. There was also considerable damage caused during the Williamite sieges in the 1690s and so the castle has been repaired and restored on a number of occasions.” [13]

It is a good place here to review the Siege of Limerick. Near the castle is the Treaty Stone: apparently the Treaty of Limerick, which was signed by, amongst others, John Baggot, was signed on this stone, which was later memorialised on a plinth. A series of plaques on the ground around the stone tells us the story of the Siege of Limerick:

“The War of Two Kings. James II, a Catholic, was king of England. Parliament, unhappy with the power that James II had given to the Catholics, invite William and Mary to take over the throne. William of Orange was married to Mary the Protestant daughter of James. William arrives in England. James, fearing for his life, flees to France and gets support from his cousin Louis XIV, William’s enemy. James lands at Kinsale.“

“William and Mary are crowned King and Queen of England. A French army of 7000 men arrive in Ireland to help James regain his crown.

“King William arrives in Carrickfergus with a large army, aiming to take Dublin. Battle of the Boyne. James’ army had 25,000 poorly equipped Irish and French soldiers. William had 36,000 experienced soldiers from all over Europe. King William is victorious.”

King William sent General Schomberg first, who landed in Carrickfergus on 14th June 1690 with 300 troops.

The plaques continue the story: “July 2nd 1690 James flees to France. By the 2nd July, most of the army had gathered in Limerick with Tyrconnell [Richard Talbot (1630-1691), 1st Duke of Tyrconnell] in charge. Limerick, an important port, was the second largest city in the country, with 1000 inhabitants. The Irish military in Limerick had few weapons. A small force of French cavalry were with the Irish cavalry on the Clare side of the Shannon. Their leader was Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan [1620-1693].”

“First Siege of Limerick. King William’s army began to set up camp while they waited for their heavy guns and ammunition to arrive from Dublin. Aug 10th 1690, In a daring overnight raid Sarsfield attacked the siege train at Ballyneely. King William continued his siege but massive resistance from the Jacobite army and the people of Limerick, plus bad weather, forced him to call off the siege.“

“King William returned to England leaving Baron de Ginkel in charge. Cork and Kinsale surrendered to William’s army. Sarsfield rejects Ginkel’s offer of peace. More French help arrives in Limerick as well as a new French leader, the Marquis St. Ruth. Avoiding Limerick, Ginkel attacked Athlone, which guarded the main route into Connaght. 30th June 1691, Athlone surrendered. St. Ruth withdrew to Aughrim. 12th July 1691 The Battle of Aughrim. The bloodiest battle ever fought on Irish soil. The Jacobites were heading for victory when St. Ruth was killed by a cannonball. Without leadership the resistance collapsed and by nightfall, the Williamites had won, with heavy losses on both sides. Most of the Jacobites withdrew to Limerick.“

There is a John Baggot who fought in the Battle of Aughrim, and lost an eye. He later went to France with the Wild Geese, and served in the court of James II and “James III” (his followers called him James III although he was not the recognised king).

“The city walls had been strengthened since the previous year. Tyrconnell died in mid-August and the promised help from Louis XIV had not yet arrived. The Second Siege of Limerick. Ginkel and the Williamites reached Limerick and took up positions on the Irishtown side. They bombarded the city daily with cannon. They managed to break down a large section of the walls at English town, but could not get into the city. With a large English fleet on the Shannon, the city was cut off and almost completely surrounded. Sept 22nd 1691 Ginkel’s army attacked the Jacobites who were defending Thomond Bridge. The drawbridge was ordered to be raised too soon and about 600 Irish were killed or drowned. This had a profound effect on the morale of the garrison. A council of war was held and the Jacobites decided to call a truce. Leaders from both sides saw that they could gain more by ending the fighting and the discussions were conducted with great courtesy. The Treaty was finally signed on October 3rd 1691, reputedly on the Treaty Stone.“

“Article Civil and Military, agreed on the 3rd day of October 1691, between the Right Honourable Sir Charles Porter, Knight, and Thomas Coningsby, Esq, Lords Justices of Ireland, and his Excellency the Baron de Ginkel, Lieutenant General, and the Commander in Chief of the English army, of the one part and Sarsfield and his followers on the other. The treaty had civil and military sections. The Civil articles promised freedom to practice their religion to Catholics, but in the years after 1691, harsh laws were passed against Catholics known as the Penal Laws.

“The broken treaty embittered relations between the English and Irish for two centuries.

“The military parts of the Treaty allowed the Irish Jacobites to join the French army. Most of the Irish (about 14,000 approx.) went to France with Sarsfield. Some of their wives and children also travelled to France. These exiles were known as the Wild Geese. The Wild Geese became part of the French army, which included Irish regimens until the French Revolution. Wine Geese: some of the Wild Geese got into the wine trade, where their names live on today, names such as Michael Lynch, who fought in the battle of the Boyne, Phelan, Barton, and Richard Hennessy of Hennessy cognac.“

John Baggot’s sons (sons of Eleanor Gould), John and Ignatius, became soldiers and one fought for France and one fought for Spain.

“In 1791 the British Army built military barracks suitable for up to 400 soldiers at the castle and remained there until 1922. In 1935 the Limerick Corporation removed some of the castle walls in order to erect 22 houses in the courtyard. These houses were subsequently demolished in 1989 when the castle was restored and opened to the public.” [13]

10. Odellville House, Ballingarry, Co. Limerick – section 482

www.odellville.simplesite.com

Open dates in 2024: May 1-31, June 1-30, Aug 17-25, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €8, student/OAP/child €4

The National Inventory tells us it is a detached five-bay two-storey over basement house, built c. 1780, with later two-storey extension to rear (south). It continues: “Odell Ville is typical of the small country houses of rural Ireland, often associated with the gentleman farmers of the eighteenth century. The retention of historic fabric such as sliding sash windows, fine tooled limestone details and modest door with its stepped approach all contribute positively to the building’s character. It was once the house of T. A. O’Dell, Esq. Athough of a modest design, the overall massing of the house makes a strong and positive impact on the surrounding countryside. The associated gate lodge adds further context and character to the site.” [14]

11. Mount Trenchard House and Garden, Foynes, Co. Limerick – section 482

Open dates in 2024: : June 3-7, 10-14, 17-21, 24-28, July 1-5, 8-12, 15-19, 22-26, 29-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student €8, child €5

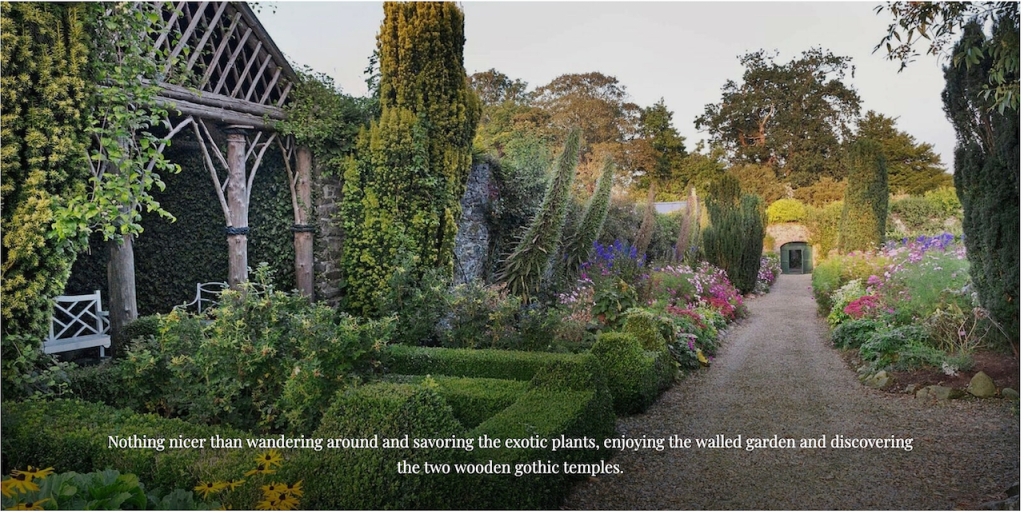

We visited Mount Trenchard during Heritage Week 2022 – see my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/04/01/mount-trenchard-house-and-garden-foynes-co-limerick/

12. The Turret, Ryanes, Ballyingarry, Co. Limerick V94 HV24 – section 482

Open dates in 2024: May 1-31, Mon-Sat, Aug 1-31, Sept 2-21, Mon-Sat, 12 noon-4pm

Fee: adult €5, OAP/child/student/ free

We visited The Turret during Heritage Week 2022: see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/03/23/the-turret-ballingarry-co-limerick-v94-hv24/

14. The Old Rectory, Rathkeale, Co. Limerick – section 482

Open dates in 2024: May 4-Nov 30, Saturday and Sundays, National Heritage Week, Aug 17-25, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €8, child/OAP/student €3

Places to stay, County Limerick:

1. Adare Manor, Limerick – hotel €€€

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

“Originally a two storey 7 bay early C18 house with a 3 bay pedimented breakfront and a high-pitched roof on a bracket cornice; probably built ca 1720-1730 by Valentine Quin [1691-1744], grandfather of the first Earl of Dunraven [Valentine Richard Quin (1752-1824)].”

David Hicks tells us in his Irish Country Houses, A Chronicle of Change that Valentine Quin converted to Protestantism to retain the Quinn lands. In the 1780s his son Windham remodelled the Georgian house in a neoclassical manner and made many improvements including the addition of another storey.

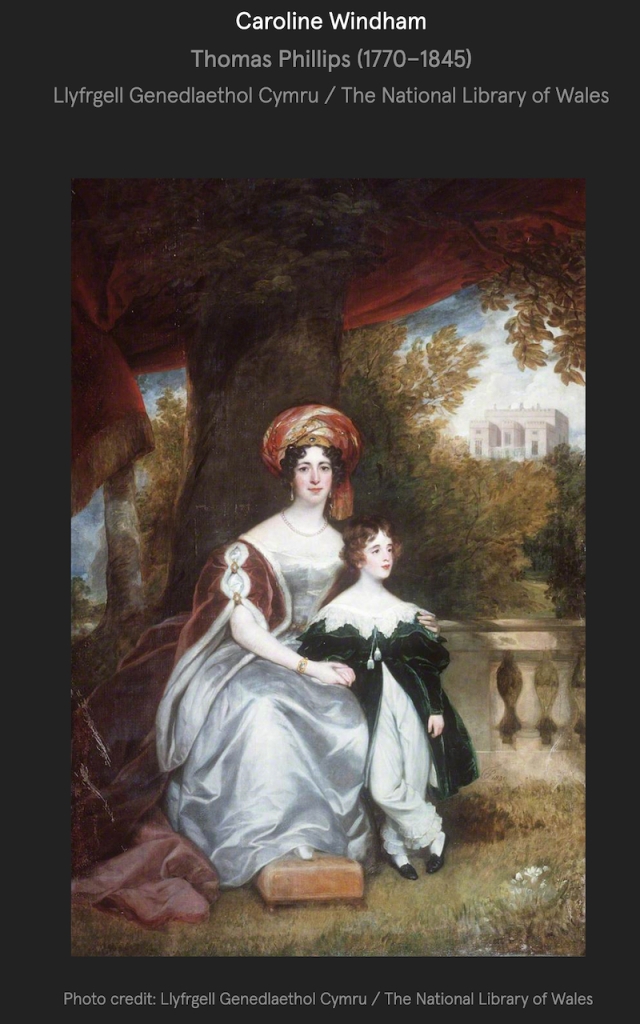

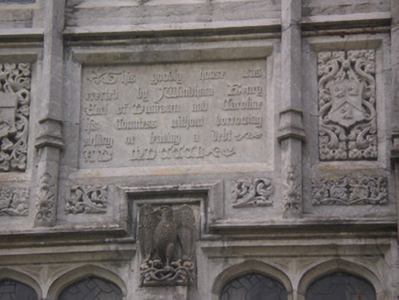

His son Valentine Richard Quin inherited but due to debt, moved to England to live a more frugal lifestyle. He was created 1st Baronet Quin, of Adare, Co. Limerick in 1781, and 1st Baron Adare, of Adare in 1800 for voting for the Act of Union, and finally 1st Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl in 1822, Dunravan being chosen in honour of his daughter-in-law Caroline Wyndham and her home Dunraven Castle in Wales. His son Windham Henry (1782-1850), 2nd Earl, returned to the heavily indebted Irish estate in 1801 and managed to reduce debts by leasing land. He was elected MP for Limerick in 1806. He was a supporter of the Union but also an advocate of Catholic emancipation. In 1810 he married Caroline Wyndham, heiress to large estates in Wales, and as a result of her large inheritance, the Quin family name was changed to Wyndham-Quin. The Quin and Wyndham heraldic shields decorate the entrance to the manor. An inscription in Gothic lettering on the south front of the manor reads “This goodly house was erected by Windham Henry Earl of Dunraven and Caroline his Countess without borrowing, selling or leaving a debt.”

Bence-Jones continues: “From 1832 onwards the 2nd Earl, whose wife was the wealthy heiress of the Wyndhams of Dunraven, Glamorganshire, and who was prevented by gout from shooting and fishing, began rebuilding the house in the Tudor Revival style as a way of occupying himself; continued to live in the old house while the new buildings went up gradually behind it only moving out of it about ten years later when it was engulfed by the new work and demolished.

“To a certain extent Lord and Lady Dunraven acted as their own architects, helped by a master mason named James Conolly; and making as much use as they could of local craftsmen, notably a talented carver. At the same time, however, they employed a professional architect, James Pain; and in 1846, when the house was 3/4 built, they commissioned A.W. Pugin to design some of the interior features of the great hall. Finally, between 1850 and 1862, after the death of the second Earl, his son, the 3rd Earl [Edwin Richard Wyndham-Quin (1812-1871)], a distinguished Irish archaeologist, completed the house by building the principal garden front, to the design of P.C. [Philip Charles] Hardwick. The house, as completed, is a picturesque and impressive grey stone pile, composed of various elements that are rather loosely tied together; some of them close copies of Tudor originals in England, thus the turreted entrance tower, which stands rather incongruously at one corner of the front instead of in the middle, is a copy of the entrance to the Cloister Court at Eton.“

Bence-Jones continues: “The detail, however, is of excellent quality; and the whole great building is full of interest, and abounds in those historical allusions which so appealed to early-Victorians of the stamp of the second Earl, his wife and son. As might be expected, Hardwick’s front is more architecturally correct than the earlier parts of the house, but less inspired; a rather heavy three storey asymmetrical composition of oriels and mullioned windows, relieved by a Gothic cloister at one end and dominated by an Irish-battlemented tower with a truncated pyramidal roof, surmounted by High-Victorian decorative iron cresting.“

The Archiseek website tells us:

“The structure is a series of visual allusions to famous Irish and English homes that the Dunravens admired. It is replete with curious eccentricities such as the turreted entrance tower at one corner rather than in the centre, 52 chimneys to commemorate each week of the year, 75 fireplaces and 365 leaded glass windows. The lettered text carved into the front of the south parapet reads: “Except the Lord build the house, the labour is but lost that built it.” The elaborate decoration is a miracle of stonework – arches, gargoyles, chimneys and bay windows. The interior spaces are designed on a grand scale. One of the most renowned interior spaces is the Minstrel’s Gallery: 132 foot long, 26-1/2 foot high expanse inspired by the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles and lined on either side with 17th Century Flemish Choir Stalls.

“Other architects to have collaborated with the Earl include Lewis [Nockalls] Cottingham, Philip Charles Hardwick, and possibly A.W.N Pugin who designed a staircase and ceiling.” [17]

Mark Bence-Jones continues: “The entrance hall has doorways of grey marble carved in the Irish Romanesque style; the ceiling is timbered, the doors are covered in golden Spanish leather. The great hall beyond, for which Pugin provided designs, is a room of vast size and height, divided down the middle by a screen of giant Gothic arches of stone, and with similar arches in front of the staircase, so that there are Gothic vistas in all directions. A carved oak minstrels’ gallery runs along one side; originally there was also an organ-loft. From the landing of the stairs, a vaulted passage constitutes the next stage in the romantic and devious approach to the grandest room in the house, the long gallery, which was built before the great hall, in 1830s; it is 132 feet long and 26 feet high with a timbered roof; along the walls are carved C17 Flemish choir stalls and there is a great deal of other woodcarving, including C15 carved panelling in the door.

“The other principal reception rooms are in Hardwick’s garden front; they have ceilings of Tudor Revival plasterwork and elaborately carved marble chimneypieces; that in the drawingroom having been designed by Pugin.“

Sean O’Reilly writes in his book Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life.

“Nowhere is the creativity of Adare more apparent than in the Great Hall and its associated spaces. Enclosed by screens of giant and more modest arches, round and pointed, surrounded by corridors, staircases and steps flying in an apparently conflicting succession of directions, and with galleries breaking through walls, not to mention the ubiquitous antlers of the Irish elk, the great hall was one of the most picturesque interiors of its day. Lady Dunraven described the room as being ‘peculiarly adapted to every purpose for which it may be required,’ observing that ‘it has been frequently used with equal appropriateness as a dining room, concert-room, ballroom, for private theatricals, tableaux vivants and other amusements.’ ” [18]

In 1834 the Dunravens visited Antwerp and purchased the woodcarvings to adorn the gallery. In 1835 they purchased a highly carved and decorative choir stall from St. Paul’s church in Antwerp. Local woodcarvers in Limerick then made an exact copy of the seventeenth century original in order to form a pair.

O’Reilly writes: “If the hall is the most complex space, the most dramatic is the gallery, a huge timber-roofed space rising through two storeys and stretching nearly forty-five metres. With its architectural details, pictures and furnishings, the idea, as Cornforth so well expressed it, was to ‘create 250 years of history overnight.’ The family history from the twelfth century is traced in Willement’s stained glass and portraits – both family heirlooms and acquisitions – which carry the story through in more intimate, if also more vague terms. Seventeenth century Flemish stalls, purchased by the Dunravens during their Continental tour of 1834-36, add to the ambiguous combination of old and new.” [18]

O’Reilly adds: “It was Pugin’s successor, the English architect P.C. Hardwick, who developed the next and final major phase of work at Adare. This involved the laying out of the surrounding terraces, and the completion of the southern range, that which looks across to the river and occupies the site of the original classical house. Although Hardwick’s work embodies the professional finish of the later nineteenth century, it possesses none of the amateur exuberance of the earlier work. Yet his patron, the 3rd Earl, was to establish himself as one of the foremost authorities of Irish antiquities. He was a friend of the celebrated Irish antiquary George Petrie, and collated the material for the posthumously published Notes on Irish Antiquities, one of the most significant antiquarian publications of the century.” [18]

The principal reception rooms in Hardwick’s garden front have ceilings of Tudor Revival plasterwork and elaborately carved marble chimneypieces, that in the drawing room was designed by Pugin. The drawing room, library and other reception rooms in the garden front only came into use for the coming of age of the future fourth Earl of Dunraven in 1862. The third Earl married Augusta Charlotte Gould, whose grandmother was Mary Quin, daughter of Valentine Quinn who built the first house at Adare. Augusta’s sister Caroline married Robert Gore-Booth, 4th Baronet of Lissadell, County Sligo, a section 482 property.

A daughter of the 3rd Earl, Mary Frances, married Arthur Hugh Smith-Barry, 1st and last Baron Barrymore of Fota House in County Cork (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/01/19/office-of-public-works-properties-munster/ )

The 4th Earl had no sons and he was succeeded by his cousin, Windham Henry Wyndham-Quin (1857-1952), grandson of the 2nd Earl of Dunraven. He lived at Adare for twenty-six years, until his death in 1952. He was married to Eva Constance Aline Bourke, daughter of the 6th Earl of Mayo. It was their son, Richard Southwell Windham Robert Wyndham-Quin, 6th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, who made the difficult decision to sell Adare Manor due to difficult economic climate of the 1980s in Ireland. It took a while to find a suitable buyer. Unable to bear the expense of maintaining Adare Manor, the 7th Earl sold it and its contents in 1984.

Mark Bence-Jones adds: “The house stands close to the River Maigue surrounded by a splendid desmesne in which there is a Desmond castle, and a ruined medieval Franciscan friary; one of three monastic buildings at Adare, the other two having been restored as the Catholic and Protestant churches.”

Among the trees southwest of the Manor House are Ogham Stones, which were brought to Adare Manor from Kerry by Edwin, the 3rd Earl of Dunraven. Ogham Stones date from the early 5th Century to the middle of the 7th Century. They are mainly Christian in context and are usually associated with old churches or early Christian burial sites. Ogham inscriptions are in an early form of Irish, frequently followed by Latin inscriptions and often read from the bottom upwards.

2. Ash Hill, Kilmallock, Co Limerick V35 W306 – section 482, Hidden Ireland accommodation €

www.ashhill.com

Tourist Accommodation Facility

As a Tourist Accommodation Facility, Ash Hill doesn’t need to open to the public, but it has listed Open Days in 2024 – contact them in advance to ensure that it is convenient for the owners for a visit: May 1- Oct 31, 10am-4pm

Fee: free to visit.

The website tells us: “Ash Hill is a large, comfortable Georgian estate, boasting many fine stucco ceilings and cornices throughout the house. For guests wishing to stay at Ash Hill, we have three beautifully appointed en-suite bedrooms, all of which can accommodate one or more cots…Open to the public from January 15th through December 15th. Historical tours with afternoon tea are easily arranged and make for an enjoyable afternoon. We also host small workshops of all kinds, upon request…For discerning guests, Ash Hill can be rented, fully staffed, in its entirety [comfortably sleeps 10 people]. Minimum rental 7 days.”

We treated ourselves to a stay during Heritage Week 2022 – https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/04/06/ash-hill-kilmallock-co-limerick/

3. Ballyteigue House, Bruree, County Limerick – self-catering whole house accommodation, rental per week. €€ for two, € for 4-10

The National Inventory tells us it is a three-bay two-storey country house, built c. 1850, having later porch to front (south).

“Ballyteigue House accommodation Limerick can accommodate nine people comfortably and there is a Courtyard Cottage which can accommodate an extra 6 people.

“The House available for holiday lettings consists of 5 Bedrooms, 4 double or twin, and a single room. All rooms have their own bathroom.

“Bruree is where President De Valera spent the early part of his life and went to school.“

4. Deebert House, Kilmallock, County Limerick – B&B and self-catering http://www.deeberthouse.com/

The National Inventory tells us it was built in 1804.

5. The Dunraven, Adare, Co Limerick €

https://www.dunravenhotel.com/

The website tells us: “The Dunraven is a stylish, luxury, family-run hotel situated in the heart of Adare, a picturesque and world renowned village in Co. Limerick. This Four Star Luxury Hotel is one of the oldest establishments in Ireland and dates back to the Eighteenth Century.”

It’s not a historic house, but it is old!

Whole house rental County Limerick

1. Ballyteigue House, Bruree, County Limerick – self-catering whole house accommodation, rental per week. €€ for two, € for 4-10 – see above

2. Fanningstown Castle, Adare, County Limerick – sleeps 10

https://fanningstowncastle.com/

The website tells us about the history of the castle:

“Fanningstown Castle is situated in the fertile valley of the river Maigue, in Co. Limerick. It lies in the barony of Coshma (Coshmagh) which, meaning ‘Foot of the Plain’ or ‘Bank of the Maigue,’ describes this location. The area of the barony coincides with the territory of the Celtic people, the Ui Cairbre Aobhdha.

“In the late twelfth and early thirteenth century the invading Anglo-Normans identified the strategic importance of the Maigue, and gradually established a series of fortresses along its western shore, some a rebuilding of existing forts. An early castle was built at Newtown near the mouth of the river, another near the ford at Croom by 1215 when it was granted to Maurice Fitzgerald, an old fort at Adare was walled, and by 1280 there was a castle on raised ground near a bridging point on the river at Castleroberts.“

“There was a castle at Fanningstown by 1285. Situated a few miles from the bank of the river behind Castleroberts Fanningstown seems to have been part of a second line of defence. It is difficult to date the remaining castle ruins which consist of a small, almost square chamber without upper floors or roof, and a round staircase tower which, pierced with arrow-slit windows, rises about three floors, but from which the staircase and roof have been removed.

“There is the remains of a bartizan (a turret corbelled out from the wall on cut stone corbels, used for defence) on the west corner. This castle was incorporated into one corner of a battlemented bawn wall which enclosed a large courtyard.

“It is possible that the other three corners were given towers or the external appearance of towers. There is one of the latter on the NE corner, surmounted by double battlements which are typical of Irish medieval castellated architecture. It could be a nineteenth-century addition, like the one on the NE corner which was incorporated into the new house, of which more later.“

“The difficulty in dating Irish castles for which there is little documentary record derives from the fact that architectural features are unreliable as a source. Medieval castellated styles tended to be simple and conservative, stone work varied little over the centuries, attacks often left the structures badly damaged or ruined. However, the small size of Fanningstown Castle suggests that this is the ground plan of an unimportant, probably primarily defensive structure. In possession of the Norman Maurice family by 1285, along with the castle at Adare, Fanningstown castle and the cantred of which it was a part, and into which English and Welsh settlers may well have been introduced, were an integral part of the Norman feudal system.

“A seventeenth-century description of Fanningstown draws attention to a single plowland, a thatched house, and an orchard. These could have sustained a steward charged with the upkeep of the castle. They might well have lain safely within the bawn walls, though it is not impossible that the present extensive walled orchard adjacent to the bawn could have had a seventeenth-century or earlier origin.

“While Fanningstown lingered as a defensive outpost Adare Castle expanded, acquiring a massive stone keep, separate hall, stables, kitchen, dungeon, portcullis, all of which are being currently restored. Croom Castle too grew, becoming the principal seat of the Earl of Kildare. The castle, renovated in the nineteenth century is still inhabited.

“Unfortunately Fanningstown does not surface in the historical record until the late sixteenth century. By this time the English, conscious that their power was slipping from them in Ireland, were determined to reassert themselves. One strategy was the appointing of a new breed of ambitious administrator such as Sir Warham St. Leger, who became Lord Justice in 1569.

“With the granting of the tithes of Ballyfenninge to him in 1567 Fanningstown had fallen into the English orbit. This was important for the Fitzgerald earldom of Desmond, which controlled large swathes of Munster, including many of the old Norman fortresses, were opposing English efforts at centralisation.

“In 1569 this resolved itself into rebellion, which lasted until James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald submitted in 1573 before going into exile. When he returned with fresh soldiers in 1579 a new phase in the rebellion started. It was to Fanningstown that Sir William Pelham, now Lord Justice, camped with a large force, summoned the Earl of Desmond to meet him.“

“When Desmond failed to make the rendezvous Pelham charged him with treason and instituted a scorched earth policy which reduced Munster to a famine that lived long in the folk memory. Gradually Pelham captured the castles that had supported Desmond; Limerick, Croom, Kilmallock, Lough Gur, and finally Askeaton.

“The Rebellion was finally crushed in 1583 with the killing of the Earl of Desmond. Fanningstown was granted to the succeeding Lord Justice, Sir H. Wallop, in 1592.

“In the mid-seventeenth century English efforts to bring Ireland to heel were spear-headed by Oliver Cromwell’s ferocious and successful military campaign. Planning to reward his soldiers with Irish land Cromwell ordered that a survey of who held what was made. It was completed in 1656 and called the Civil Survey. This reveals that Fanningstown had slipped from English control and was now in the possession of Edmund Fanning, a member of an old Anglo-Norman family that had remained Catholic and was vehemently opposed to Cromwell.“

“In Limerick City where Cromwell’s general, Henry Ireton, had led a six-month siege, another member of the family, Dominick Fanning, an alderman, had led the resistance. By October 1651 Ireton had prevailed and Dominick Fanning was one of the twenty who were to loose ‘lives and property.’ He had escaped but returned to the city to retrieve some money. As his wife refused to receive him he hid in his ancestor’s tomb in St Francis Abbey for three days and nights. Emerging to warm himself at a guard’s fire he was identified by a former servant who denounced him to Ireton’s soldiers.“In Limerick City where Cromwell’s general, Henry Ireton, had led a six-month siege, another member of the family, Dominick Fanning, an alderman, had led the resistance. By October 1651 Ireton had prevailed and Dominick Fanning was one of the twenty who were to lose ‘lives and property.’ He had escaped but returned to the city to retrieve some money. As his wife refused to receive him he hid in his ancestor’s tomb in St. Francis Abbey for three days and nights. Emerging to warm himself at a guard’s fire he was identified by a former servant who denounced him to Ireton’s soldiers.

“One of the few remaining medieval houses in Limerick is Fanning’s Castle, on Mary Street, a late medieval stone tower house, once five storeys high, with a turret staircase, ogee windows and battlements. This former residence of Dominick Fanning was one of the houses that lined the main street of English Town and so impressed foreign visitors. It is eloquent of the prominent position of a family that was supplying bailiffs and mayors for the city from the mid-fifteenth century until Cromwell’s victory, when a new group of English Protestant families became dominant.

“Anna Fanning, who died in 1634, is the only Fanning remembered in St. Mary’s Cathedral in the city; a stone slab on the floor of the chapel of St. Nicholas and St. Catherine bears her name.“

“The eighteenth century was a period of relative peace in Ireland. This was reflected in the architecture. Defence, finally, was no longer an issue. The old defensive structures could be demolished or skilfully amalgamated into the new classical style where light and space were a priority.

“At Fanningstown part of the bawn wall was taken down and a new house erected. The castle was left to one side as a ruin. Nothing of this new house now remains. It was, however, still in existence when the Ordnance Survey cartographers visited in 1840, and from their map it is possible to see that the new house faced the old courtyard with a long impressive façade and a bow-fronted entrance. The orchard was to the rear. An eighteenth-century cut stone opening can be seen in the eastern wall. Fanningstown was now entered by a road from the east which ran off the Patrickswell-Croom Road, marked by a gate lodge which still stands.

“This house seems to have been uninhabited by 1850. By then the townland of Fanningstown was largely owned by Hamilton Jackson. Most of this was rented to tenants, but he held over 280 acres in fee which included a number of ‘offices’ but no house, suggesting that the house was in ruins.“

“Other landowners in the neighbourhood were investing in their properties. Two Limerick historians, Fitzgerald and McGregor, present a picture of neat, well-kept houses and demesnes in 1826. Croom Castle stands out. John Croker had ‘fitted it up and furnished [it] in the castellated style, with great taste and judgement. The gardens, shrubberies, and gravel walks are kept in the neatest order, and from the house is a very fine view up the River Maigue which winds along in a majestic stream, and of a handsome Chinese bridge …’

“Adare too, where a classical mansion had been built in the eighteenth century, was acquiring a Gothic character. This project, started in 1832, was the preoccupation of successive Earls of Dunraven who employed a talented local stone mason, James Connolly, and various well-known architects who specialised in the Gothic Revival. James Pain, A.W. Pugin, P.C. Hardwick. The result was a splendid mix of historicism and fantasy in which Irish double-stepped battlements rubbed shoulders with English towers and Romanesque doorways.“

“Elsewhere in Co. Limerick the Gothic style was also being vigorously pursued. At Castle Matrix near Rathkeale the Southwell family modernised a fifteenth-century keep in 1837, while at Castle Oliver the Misses Oliver-Gascoigne built a Gothic fantasy to give employment after the Famine in c 1850. At nearby Dromore in Pallaskenry, Lord Limerick commissioned E.W. Godwin in 1867 to design a castle based on a survey of old Irish castles.

“So it is perhaps not surprising that (sometime between 1850 and 1865) Hamilton Jackson or his successor, David Vandeleur Roche [1833-1908, 2nd Baronet Roche, of Carass, Co. Limerick], who acquired the property in 1860, should consider unearthing the Gothic potential at Fanningstown. He employed a Cork architect, P. Nagle, and together they decided to demolish the eighteenth-century house, reconstruct the bawn walls, build a house along the entire east wall of the courtyard facing outwards and make a new entrance from Adare Road to the west.“

“At the corner opposite the old castle Nagle designed a three-storey tower serviced by a staircase (which may have been taken from the old tower) in a round tower which was a direct echo of the thirteenth-century building.

“Between these two towers he erected a gateway with monumental double battlements and the battered (outward sloping) walls of the towers.

“He reproduced a bartizan on the square tower (it forms a delightful cupboard in one of the bedrooms), introduced battlements to all the walls giving them the appearance of machicolations by projecting them on cut stone corbels (in medieval castles this would have formed a parapet through which missiles could be dropped on the enemy), and gave the ground floor windows and door on the entrance facade ogee windows.“He reproduced a bartizan on the square tower (it forms a delightful cupboard in one of the bedrooms), introduced battlements to all the walls giving them the appearance of machicolations by projecting them on cut stone corbels (in medieval castles this would have formed a parapet through which missiles could be dropped on the enemy), and gave the ground floor windows and door on the entrance facade ogee windows.“

“The other windows were rectangular casements which, a nineteenth-century watercolour indicates, once had window frames of pointed arches. The old tower was made into a dove cot; the pigeon holes can still be seen. The result is a restrained nineteenth-century version of the medieval castle in which the integrity of the bawn and castle has been retained. This was an unusual solution, and gives this modest-sized castle a pleasing integrity.

“Inside Nagle designed ogee arches above the window recesses in the thick walls, vaulted ceilings on the ground floor and Gothic fireplaces were acquired for the rooms. Despite some additions Fanningstown Castle retains much of the character of this nineteenth-century building in which the medieval past so easily seems to break through.“

“In 1890 the castle came into the possession of J.F. Bannatyne, whose family owned a successful milling business in Limerick. They had built a state-the-art mill at Limerick docks in 1874 which still stands and is known as Bannatyne Mills. The 1901 census indicates that Bannatyne did not live in Fanningstown. Instead, the castle and adjoining buildings were inhabited by five different families who mainly serviced the dogs and horses kept for hunting.

“In 1936 the estate was acquired by the Normoyle family, who are still in residence. They are currently working on the restoration of the nineteenth-century castle.”

3. Flemingstown House, Kilmallock, Co. Limerick, Ireland – whole house accommodation, up to 11 guests €€€ for two for a week, € for 4-11

4. Glin Castle, County Limerick – whole house rental.

You can see lovely photographs of the castle, inside and out, on the website.

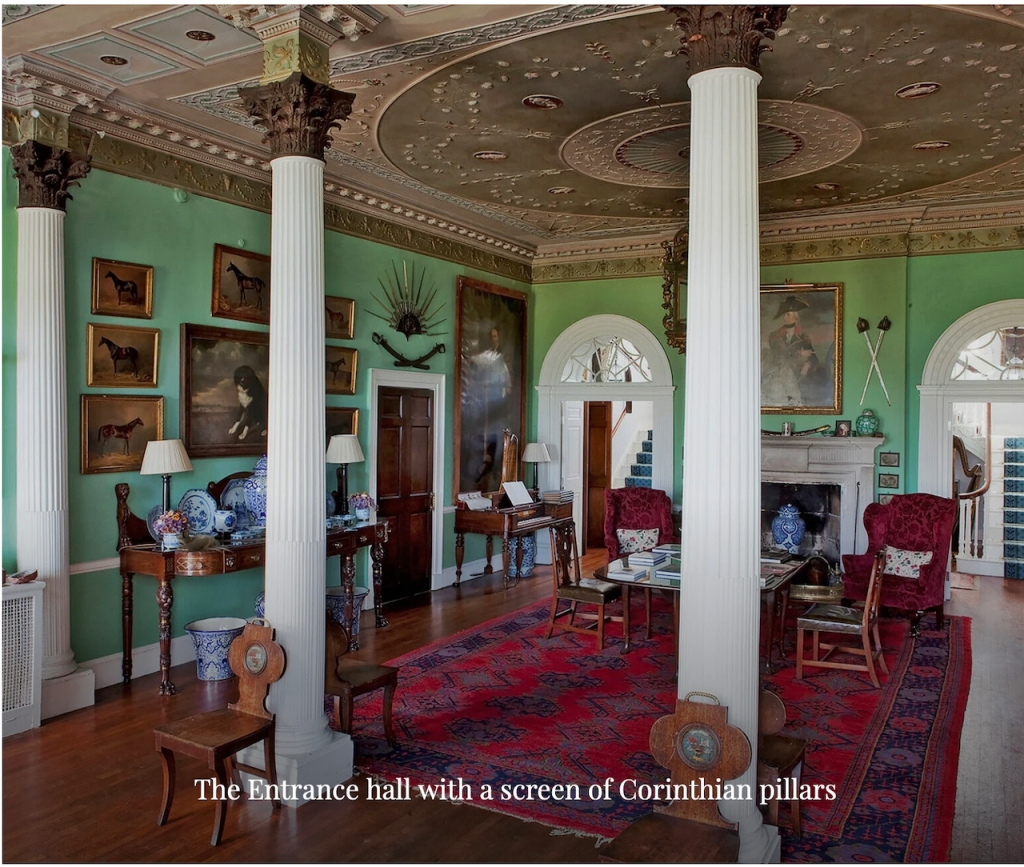

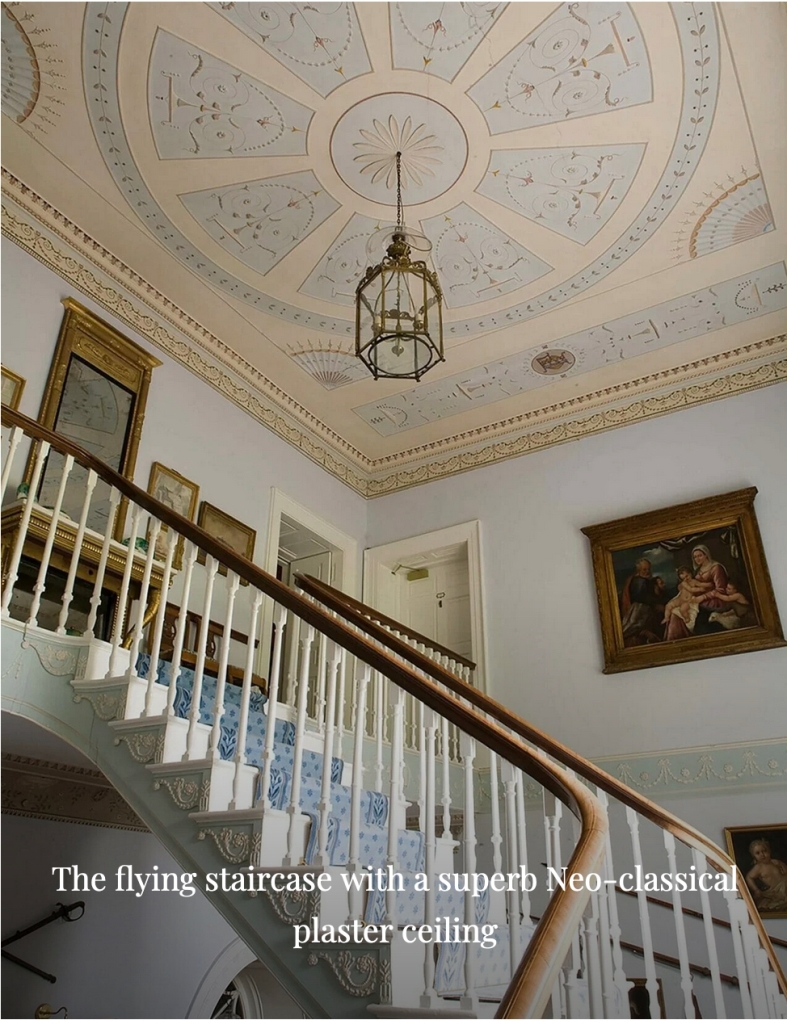

The website tells us: “The castle comprises 5 exquisite reception rooms filled with a unique collection of Irish 18th century furniture. The entrance hall with a screen of Corinthian pillars has a superb Neo-classical plaster ceiling and the enfilade of reception rooms are filled with a unique collection of Irish 18th century mahogany furniture. Family portraits and Irish pictures line the walls, and the library bookcase has a secret door leading to the hall and the very rare flying staircase.“

“Upstairs there are 15+ individually decorated bedrooms, each with its own private bathroom. Colourful rugs and chaise longues stand at the end of comforting plump beds. Pictures and blue and white porcelain adorn the walls. The bedrooms at the back of the castle overlook the garden, while those at the front have a view of the river.“

The website tells us of the history:

“The FitzGeralds first settled here in the 1200’s at nearby Shanid Castle following the Norman invasion of Ireland. Their war cry was Shanid Abu! (Shanid forever in Gaelic). In the early 14th century the Earl of Desmond, head of the Geraldines, made hereditary Knights of 3 illegitimate sons he had sired with the wives of various Irish chieftains, creating them the White Knight, the Green Knight of Kerry and the Black Knight of Glin. For seven centuries they defended their lands against the troops of Elizabeth I, and during the Cromwellian plantation and Penal laws.

“Coming into the hall with its Corinthian columns and elaborate plaster ceiling in the neo classical style, one can see straight ahead among a series of family portraits, some already mentioned, the picture of Colonel John FitzGerald [(1765-1803)the 23rd Knight of Glin], the builder of the house, wearing the uniform of his volunteer regiment the Royal Glin Artillery. In his portrait, which hangs over the Portland stone chimneypiece, he is proudly pointing at his cannon. In May 1779 Colonel John’s father, Thomas FitzGerald, whose portrait in a blue coat is on the left of the dining room door, wrote to Edmund Sexton Pery the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons to warn him that a French naval invasion was expected off the coast. There were rumours that the American privateer Paul Jones had sailed up the Shannon to Tarbert after he had defeated an English ship in Belfast Lough in the summer of 1779. France and Spain had declared war on England and were supporting the American colonists in the War of Independence. Panic spread among the gentry and nobility of Ireland in case the country should be left unprotected in the face of an invasion, and the Irish Volunteer Regiments were raised between 1778 and 1783-40,000 men having been enrolled by 1779 and 100,000 by 1782. Inspired by the success of the Americans and with the strength of the Volunteers behind them, Henry Grattan and his Patriot Party demanded legislative independence for Ireland from Britain following their achievement of the abolition of trade restrictions in 1778. These stirring optimistic times were the background to the building of Glin.”

The website continues: “The new prosperity of the country was reflected in a great deal of public and private building and the accompanying extensive landscaping and tree planting showed the pride of Ireland’s ruling classes in their newly won but brief national independence-an independence which was shaken by the French Revolution and finally shattered by the Rebellion of 1798 and the ensuing Union with England in 1800. Colonel John supported this Union, though his faith in King and Country had faltered under the influence of his United Irishman brother, Gerald during the 1798 Rebellion, when his kinsman Lord Edward FitzGerald is said to have stayed at Glin. Colonel John had no political influence as all the local boroughs were in the hands of the new English settler families. This meant that unlike so many of them he did not spend money on a large Dublin house and thereby concentrated on cutting a greater dash at home.“

“Unfortunately, we have no direct information about who designed the house or the identity of the craftsmen who styled the superb woodwork such as the mahogany library bookcase with its concealed secret door, the inlaid stair-rail, the flying staircase, or the intricate plaster ceilings. This is because many of the family papers were burned by the so-called ‘Cracked Knight’ in the 1860s. Tradition tells us that the stone for the house was brought across the hills from a quarry in nearby Athea on horse-drawn sleds by a ‘strongman’ contractor called Sheehy. This is the only name connected with the building of the house that has come down to us.“

“It seems likely that Colonel John started his house sometime in the 1780s as he obviously used the same masons and carpenters as were used for two houses adjoining each other in Henry Street, Limerick, one built for the Bishop of Limerick, later Lord Glentworth, and the other for his elder brother the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons, Viscount Pery. These Limerick houses were finished by 1784 and it would seem not unlikely that they are the work of a good local carpenter/builder. Colonel John may well have been his own architect working with the excellent craftsmen that Limerick could obviously produce. The neo-classical plasterwork of the hall is possibly an exception as it is close to the work of two Dublin stuccadores, Charles Thorpe or Michael Stapleton. The motifs on the frieze reminds us of the Volunteer enthusiasm of the house for the military trophies, shields sprouting shamrocks and the full bosomed Irish harp which are to be seen on the hall ceiling all underline Colonel John’s patriotism. The French horn and the music book also reminds us that this hall doubled up as a ballroom; the music undoubtedly being played by the musicians from the artillery band. Colonel John loved music and had been taught the flute by a Gaelic music and dancing master, Seań Bán Aerach Ó Flanagán. The house stands on the banks of the widest part of the river Shannon and the snub nosed dolphins and tridents in· the corners of the main hall ceiling symbolise water, while flower-laden cornucopiae and ears of wheat represent the fruitful grasslands that surround the newly built mansion. Oval plaques with their Pompeian red background portray Roman soldiers depicting war and other figures characterise peace and justice. All this symbolism reminds us of contemporary events in the sea girt island of Ireland. This magnificent ceiling retains much of its original 18th century colouring.“

“In 1789 Colonel John married his beautiful English wife, the daughter of a rich west country squire, and her coat-of-arms are impaled with his on the hall ceiling. Her portrait hangs above her husbands to the right of the drawing room door in the hall. Her coat-of-arms on the ceiling suggests that the house was still being decorated in 1789 although the money must have been beginning to run out, because work was stopped short on the third floor, and walls remained scored for plaster and pine doors are unpainted to this day. Financial problems must have marred their brief decade together at Glin as in 1791 the Dublin La Touche Bank called in their debts going back as far as 1736 and took a case to Parliament. In June 1801 a private Act of Parliament in Westminster was passed to force part of the Glin estate to be sold in order to pay off the many ‘incumbrances’ which had accrued through the 18th century. This document mentions that Colonel John had expended ‘Six thousand pounds and upward in building a mansion house and offices and making plantations and other valuable and lasting improvements…’. Comparing costs with other roughly contemporary buildings shows us that the cut stone Custom House in Limerick cost £8,000 in 1779 and Mornington House, one of Dublin’s largest houses, was sold for the same sum in 1791, so £6,000 ‘and upwards’ was a substantial sum in those days. Colonel John’s wife Margaretta Maria Fraunceis died at one of her father’s properties, Combe Florey in Somerset a few months after the Act was passed. In 1802, 5,000 acres of Glin were sold, and Colonel John himself died in 1803 leaving an only son, and heir aged 12. In June 1803 the local newspaper the Limerick Chronicle advertised sales of the household furniture, the library, ‘a superb service of India china’, but no pictures or silver. The hall chairs and amorial sideboard in the hall survived because of their family associations but carriages, farm stock, and ‘the fast-sailing sloop The Farmer, her cabin neatly fitted up’ followed. The FitzGeralds of Glin were almost bankrupt.“

“It was only because of the long minority of John Fraunceis FitzGerald [(1791-1854), the 24th Knight] the son and heir, and the fact that there were no younger children to provide for, which saw the estate on to 1812 when he attained his majority. Educated at Winchester and Cambridge he regained the family fortunes by successful gambling and though he married an English clergyman’s daughter with no great dowry, he built the various Gothic lodges and added the battlements and sugar icing detail to the old Glin House making it into the ‘cardboard castle’ that it is today. This would have been typical of the romantic notions of the 1820s and he obviously thought that the holder of such an ancient title should be living in a castle like his medieval ancestors.“

“The top floor was never completed and other than further planting, little else was done to Glin for over a hundred years as money was scarce during the Victorian period. Over 5,000 acres were sold by 1837 and for the rest of the century the estate consisted of 5,836 acres and the town of Glin. The rent roll came to between £3,000 and £3,800 a year but with mortgages, windows jointures, and other family charges there was in 1858 a surplus of only £777 16s. 5d. brought in from the estate. Not included in this would have been the income from the salmon weirs on the Shannon. Lack of money may have been a blessing in disguise for there were few Victorian improvements at Glin though the Dublin firm of Sibthorpe redecorated the staircase ceiling and added Celtic revival monograms in two roundels and carried out some stencil work in the library and smoking room. This work would have been done in the 1860s probably at the same time that the Protestant church at the gate was being rebuilt.“

5. Springfield Castle, Drumcollogher, Co. Limerick, Ireland €€€ for 2, € for 5-25.

https://www.springfieldcastle.com

The website tells us: “Springfield Castle is situated in the heart of County Limerick on a magical 200 acre wooded estate and is approached along a magnificent three quarter mile long avenue, lined with ancient lime trees. Enjoy an exclusive relaxing stay in a one of a kind castle.“

“Accommodation for up to 25 people in a unique Irish castle we are the perfect place for your vacation, family gathering or boutique wedding in Ireland. It is the ideal place to stay in an Irish castle, Springfield is centrally located allowing you to explore many of Ireland’s fantastic gems including the Wild Atlantic Way. It is a one of a kind place where you can unwind and relax.

“Springfield castle is owned By Robert Fitzmaurice Deane the 9th Baron of Muskerry. Robert and his wife Rita are regular visitors. Robert has funded the ongoing restoration in Springfield since 2006, most recently of the garden cottage where he and Rita stay when visiting Ireland.“

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

p. 263. “(Petty-Fitzmaurice, sub Lansdowne, M/PB; Deane, Muskerry, B/PB) A three storey C18 house adjoining a large C16 tower house of the FitzGeralds, later bought by the Fitzmaurices, whose heiress married Sir Robert Deane, 6th Bt, afterwards 1st Lord Muskerry, 1775. …A two storey C19 Gothic wing with pinnacle buttresses was added at one end of C18 block, extending along one side of the old castle bawn, a smaller tower at another and outbuildings along two of the remaining sides to form a courtyard. 20C entrance gates and lodge in the New Zealand Maori style. C18 house was burnt 1923 and new house was afterwards made out of C19 Gothic wing, which was extended in the same style.”

The National Inventory tells us it is a “Gothic Revival style country house with courtyard complex, commenced c. 1740, comprising attached eight-bay two-storey country house, rebuilt c. 1925, having single-bay three-stage entrance tower. Earlier two-bay three-storey wing to side (east) having single-bay three-stage gate tower with integral camber-headed carriage arch. Tooled limestone octagonal corner turrets with pinnacles to front (south) elevation of wing gate tower, rendered octagonal turrets and pinnacles to side (west) elevation of main block. Two-bay two-storey double-pile over basement block to rear (north) incorporating possibly earlier three-stage tower to north-west. Additional lean-to stairwell block to side (west) elevation of extension block.“

“This impressive country house is situated in a picturesque location with extensive panoramic views of the surrounding countryside. The house and courtyard complex are the ancestral home of Lord and Lady Muskerry and occupies the site of an old bawn associated with the sixteenth-century tower house. The first record of a castle at Springfield is dated to 1280, when the Norman Fitzgeralds arrived. A visible mark to the tower house represents part of the roof line of an earlier eighteenth-century mansion that was built by John Fitzmaurice, a grandson of the 20th Lord of Kerry. Sir Robert Deane [1745-1818] married Ann Fitzmaurice in 1780, the sole heiress of Springfield and was a year later awarded the title Baron Muskerry. This mansion was burnt in 1921 by the IRA who were afraid that the occupying Black and Tans were going to convert the buildings into a garrison.“

Filling in the family tree, Robert Deane, 1st Baron Muskerry was the son of Robert Deane, 5th Baronet of Muskerry. He and Ann Fitzmaurice had a son who 2nd Baron but he died childless so his brother Mathew Fitzmaurice Deane (1795-1868) became 3rd Baron. His son Robert Tilson FitzMaurice Deane predeceased his father, so the title passed to his son, Hamilton Matthew Tilson FitzMaurice Deane-Morgan (1854-1929), who became the 4th Baron Muskerry. His mother was Elizabeth Geraldine Grogan-Morgan, from Johnstown Castle in County Wexford (see my entry in Places to visit and stay in County Wexford), and his father added Morgan to the Deane surname.

The 4th Baron married Flora Georgian Skeffington, daughter of Chichester Thomas Skeffington whose father was Thomas Henry Skeffington (d. 1843), 2nd Viscount Ferrard. He was born Thomas Henry Foster, son of John Foster, 1st Baron Oriel of Ferrard. He married Harriet Skeffington (d. 1831), who succeeded as 9th Viscountess Massereene, Co. Antrim, and Thomas Henry Foster changed his surname to Skeffington.

Hamiilton and Flora’s eldest son predeceased his father, and the title passed to their second son, who rebuilt the house.

“The current house was rebuilt by ‘Bob’ Muskerry, the 5th Baron [1854-1952] and follows the Gothic Revival style of the nineteenth century, with characteristic pinnacled turrets to the house and main entrance. The castellated entrance towers with tooled stone forming the main fabric of the turrets and a grand entrance door greatly enliven the façade of the building. The fine Gothic Revival style gate tower provides a glorious entrance to the substantial courtyard. A large variety of outbuildings display great skill and craftsmanship with well executed rubble stone walls and numerous carriage arches helping to maintain the historic character of the site. A curious mechanised clock controlling a mechanical calendar, lunar calendar and a bell constructed by the current owner’s great grand uncle is a mechanical masterpiece of great technical interest. Coupled with the archaeological monuments, this complex has a significant architectural value at a national level.“

The website tells us about the history:

“Steeped in history, it is the ancestral home of Lord and Lady Muskerry, whose motto Forti et fideli nihil dificile which means “nothing is difficult to the strong and faithful” underlies over 700 years of family history.

“The earliest castle at Gort na Tiobrad, the Irish name for Springfield Castle, is reputed to date from 1280 when one of the Fitzgeralds, a junior member of the Earl of Desmond’s family, married a lady of the O Coilleains, who were the Gaelic Lords of Claonghlais. He took the title Lord of Claonghlais and subsequently built a castle at Springfield. The Tower house and build circa 1480. This was the beginning of a long association of the Fitzgeralds with the area. They were patrons to Irish poets and musicians.As you enter the impressive gateway to Springfield Castle a plaque on the wall commemorates Daithi O’Bruadair, a classical Irish poet of the seventeenth century who lived at the castle with his patrons, the Fitzgerald family, recording their lives (and general events). He described Springfield Castle as “a mansion abounding in poetry, prizes and people”

“The Fitzgeralds soon became, as the saying goes “more Irish than the Irish themselves” and had an oft-times difficult relationship with the British monarchy. In 1691 they had their lands confiscated for the third and last time and Sir John Fitzgerald went to France with Sir Patrick Sarsfield to continue fighting the English there, never to return to Ireland. A younger son of the 20th Lord of Kerry, William Fitzmaurice [1670-1710], (cousins to the Fitzgeralds) then bought Springfield castle. His son, John, built a very large 3 story early Georgian mansion attached to the existing buildings. The Fitzmaurices occupied Springfield Castle until Sir Robert Deane married Ann Fitzmaurice, the sole heiress, in 1780… The 9th Baron, Robert Fitzmaurice Deane, lives and works in South Africa at present, and started restoring the castle in 2006. Robert’s sister Betty, her husband Jonathan and their children Karen and Daniel run Springfield Castle and look forward to meeting you.“

[2] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[3] https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/21803033/brackvoan-bruff-limerick

[5] https://www.limerick.ie/discover/eat-see-do/history-heritage/historic-attractions/glenquin-castle

[6] https://theirishaesthete.com/2021/09/13/glenquin-castle/

[7] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[8] https://www.countrylifeimages.co.uk/Search.aspx?s=glenstall

[10] p. 171, O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

[11] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-list.jsp?letter=K

[12] https://archiseek.com/2009/king-johns-castle-limerick/

[13] http://www.britainirelandcastles.com/Ireland/County-Limerick/King-Johns-Castle.html

[15] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-list.jsp?letter=M

[16] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2014/12/mount-trenchard-house.html

[17] https://archiseek.com/2009/adare-manor-co-limerick/

[18] p. 160. O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com