Having recently revisited the wonderful Casino (“little house”) in Marino, my entry for the Dublin Office of Public Works properties is becoming too long so I have to split it up into several entries, starting today with my entry for the Aras an Uachtaráin, the House of the President, in Phoenix Park. I will be publishing my updated Casino entry soon.

I haven’t been visiting Section 482 properties in the past two months, as I was experiencing “burnout.” As lovely as it is to visit historic properties, it is difficult arranging visits with owners. I feel like I am treading on toes, especially because I will be publishing about my visit, which I can understand alarms owners. It is so much easier visiting public properties. I am also still catching up writing about properties which I visited during the year, and sending entries to owners before publication, seeking approval.

Every weekend which passes, however, without a visit to a Section 482 property is an opportunity missed, and I do hope that the properties which I will not have time to visit this year will continue to be on the Section 482 list next year! Already since I started this project in 2019, some properties have dropped off the list and I have missed the chance to visit.

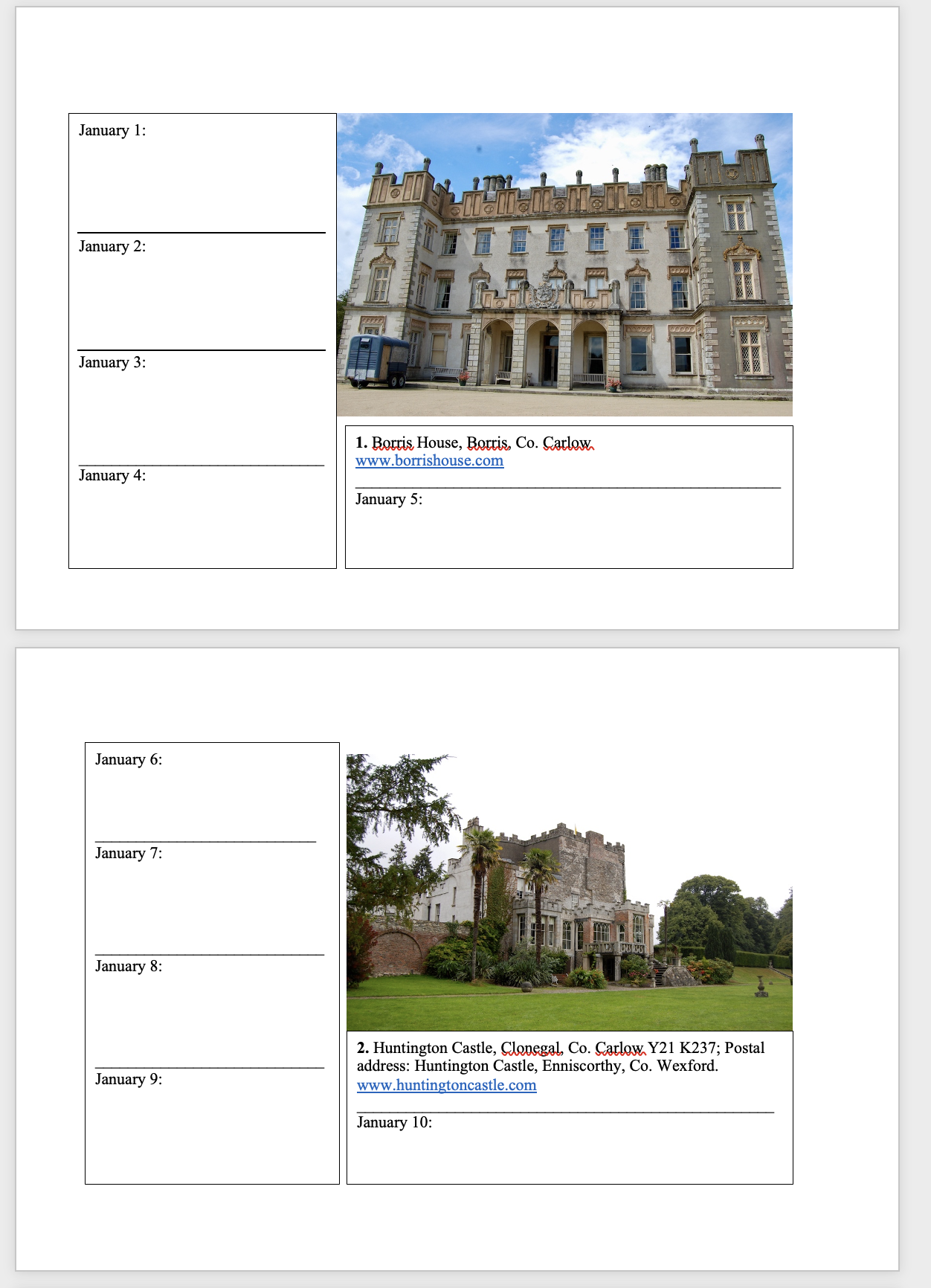

I’m already excited about the 2024 list, and I will be creating my calendars next year for the 2024 Section 482 properties, which will be available to purchase via this website. Unfortunately the Revenue does not publish the list until late February, so I won’t be able to have the calendars ready at the beginning of the new year. However, I have calendars for sale currently which do not list opening dates for the properties but have all of the pictures of the properties, and which can be used in any year. They would make a good Christmas present!

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

Office of Public Works Properties in Dublin:

1. Áras an Uachtaráin, Phoenix Park, Dublin

2. Arbour Hill Cemetery, Dublin

3. Ashtown Castle, Phoenix Park, Dublin – closed at present

4. The Casino at Marino, Dublin

5. Customs House, Dublin

6. Dublin Castle

7. Farmleigh House, Dublin

8. Garden of Remembrance, Dublin

9. Government Buildings Dublin

10. Grangegorman Military Cemetery, Dublin

11. Irish National War Memorial Gardens, Dublin

12. Iveagh Gardens, Dublin

13. Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin

14. National Botanic Gardens, Dublin

15. Phoenix Park, Dublin

16. Rathfarnham Castle, Dublin

17. Royal Hospital Kilmainham in Dublin – historic rooms closed

18. St. Audoen’s, Dublin

19. St. Enda’s Park and Pearse Museum, Dublin

20. St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

1. Áras an Uachtaráin, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8:

general enquiries: (01) 677 0095

phoenixparkvisitorcentre@opw.ie

From the OPW website:

“Áras an Uachtaráin started life as a modest brick house, built in 1751 for the Phoenix Park chief ranger. It was later an occasional residence for the lords lieutenant. During that period it evolved into a sizeable and elegant mansion.

“It has been claimed that Irish architect James Hoban used the garden front portico as the model for the façade of the White House.

“After independence, the governors general occupied the building. The first president of the Republic of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, took up residence here in 1938. It has been home to every president since then.” [1]

Phoenix Park was originally formed as a royal hunting Park in the 1660s, created by James Butler the Duke of Ormond. A large herd of fallow deer still remain to this day. Since it was a deer park it needed a park ranger. One of the park chief rangers was Nathaniel Clements (1705-1777), who was also an architect, and it was he who built the original house in 1751 which became the Aras. He was appointed as Ranger and Master of the Game by King George II in 1751. Clements was also an MP in the Irish Parliament.

Clements accumulated much property including Abbotstown in Dublin, and estates in Leitrim and Cavan. In Dublin, he developed property including part of Henrietta Street, where he lived in number 7 from 1734 to 1757. For more about him, see Melanie Hayes’s wonderful book The Best Address in Town: Henrietta Street, Dublin and its First Residents, 1720-80 published by Four Courts Press in 2020. Another house he designed, which is sometimes on the Section 482 list, is Beauparc in County Meath, and another Section 482 property, Lodge Park in County Kildare. Desmond Fitzgerald also attributed Colganstown to him, a house we visited in 2019, though this is not certain. [2]

We attended a few of President Higgins’s summer parties at the Aras. These are open to the public, by booking tickets.

The Entrance Hall of the Áras dates from 1751 from the time of Nathaniel Clements, and features a magnificent barrel-vaulted ceiling with plaster busts in the ceiling coffers.

The Council of State Room is part of the original 1751 house. The ceiling, installed by Nathaniel Clements in 1757, is by Bartholomew Cramillion and depicts three of Aesop’s Fables – the Fox and the Stork, the Fox and the Crow and the Fox and the Grapes.

The State Drawing Room is also part of the original house and the its rich gilt ceiling dates from then. The walls are lined with green silk.

The administration of the British Lord Lieutenant bought the house from Nathaniel Clements’ son Robert 1st Earl of Leitrim in 1781, to be the personal residence for the Lord Lieutenant. In 1781 the Viceroy, or Lord Deputy, was Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle. The building was rebuilt and named the Viceregal Lodge. At first it served as a summer residence, while the Viceroy stayed in Dublin Castle for the winter. The first “Lord Lieutenant” was his successor, William Henry Cavendish Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland.

The house was extended when acquired for the Viceroys to reflect its increased ceremonial importance. Mark Bence-Jones tells us that after being bought by the government, the house was altered and enlarged at various times. David Hicks tells us in his Irish Country Houses, A Chronicle of Change that all those who were awarded the position of Lord Lieutenant were from titled backgrounds and accustomed to grand country houses in England, so they found the Viceregal Lodge to be unimpressive. The 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, Philip Yorke, was the first Lord Lieutenant after the Act of Union in 1800, in 1801-1806. Yorke supported Catholic emancipation. In 1802 Yorke employed Robert Woodgate, a Board of Works architect, to make some alterations to the house, adding new wings to the house.

Additional work was carried out by Michael Stapleton – who was an architect as well as noted stuccadore – and Francis Johnston. In 1808, when Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond was Lord Lieutenant, Johnston added a Doric portico to the entrance front, and the single-storey wings were increased in height.

In 1815, Johnston extended the garden front by five bays projecting forwards, and in the centre of this front he added the pedimented portico of four giant Ionic columns which is the house’s most familiar feature.

The ballroom/state reception room was also added at this time.

It was not until the major renovations in the 1820s that the Lodge came to be used regularly by Lord Lieutenants. In the 1820s the Lord Deputy was Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, 2nd Earl of Mornington, brother of the Duke of Wellington of Waterloo fame. See my footnotes for some portraits of Vicereines and Viceroys who may have lived in the Aras.

Maria Phipps née Liddell, Marchioness of Normanby (1798-1882),Vicereine 1835-39, laid out the gardens along with Decimus Burton in 1839-40. Decimus Burton also designed many gardens in London including St. James’s Park, Hyde Park Corner and Regent’s Park. He was also an architect.

In 1849 the east wing was added, which houses the new State Dining Room. The financing of any royal visit was a matter of concern for Lord Lieutenants as they had to finance any improvements to the Viceregal Lodge. It was during the tenure of George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon (1800-1870), that Queen Victoria visited, with the idea that this would boost morale after the famine.

Jacob Owen, chief architect of the Board of Works, designed the dining room and matching drawing room in 1849.

Queen Victoria planted a Wellingtonia Gigantea tree which is still standing (others have planted trees also, including Queen Alexandria and Barak Obama, Charles de Gaulle, John F. Kennedy, Pope John Paul II and King Juan Carlos of Spain).

In 1854 the west wing was added, also designed by Jacob Owen. Queen Victoria visited again in 1853, and at this time the Viceregal Lodge was connected to the public gas supply, in order to illuminate the reception rooms and also to provide public lighting throughout Phoenix Park.

A new part of the West Wing was added for the visit of George V in 1911, during the Lord Lieutenancy of John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair.

The office of Lord Lieutenant was abolished in 1922 when the Irish Free State came into being. From 1922 until 1932 it was the residence of the Governor General of the Irish Free State. In 1922 Tim Healy was sworn in as Governor General. Over the following weeks, the former Viceregal Lodge was attacked and came under heavy fire on regular occasions.

The State Dining Room contains furniture by James Hicks of Dublin. The early 19th century fireplaces were originally a gift to Archbishop Murray of Dublin in 1812 “by his flock” for his residence at 44 Mountjoy Square, and were brought to the house in 1923, upon the sale of the house in Mountjoy Square, by the first Governor General of the Irish Free State, Tim Healy.

In 1937 when the office of President of Ireland was established, the house became the house of the president. The first President was Douglas Hyde (President of Ireland 1938-1945).

During the incumbency of President Sean T. O’Kelly, in 1948, a mid-C18 plasterwork ceiling attributed to Cramillion representing Jupiter and the Four Elements, with figures half covered in clouds, was brought from Mespil House, Dublin, which was then being demolished, and installed in the President’s Study, one of the two smaller rooms in the garden front of the original house, which we did not see.

The Mespil House ceiling was brought here at the instigation of Dr. C.P. Curran, who was also instrumental in having casts made of the plasterwork by the Francini, or Lafranchini, brothers, at Riverstown House, Co. Cork, which then seemed in danger; and which have been installed in the ballroom and in the adjoining corridor.

The State Reception Room (formerly the ballroom) features a plaster cast of a Lafranchini panel in the ceiling. The Lafranchini brothers were 18th century Swiss stuccodores who also worked on Carton and Castletown Houses. See my entry about Riverstown House https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/05/__trashed/.

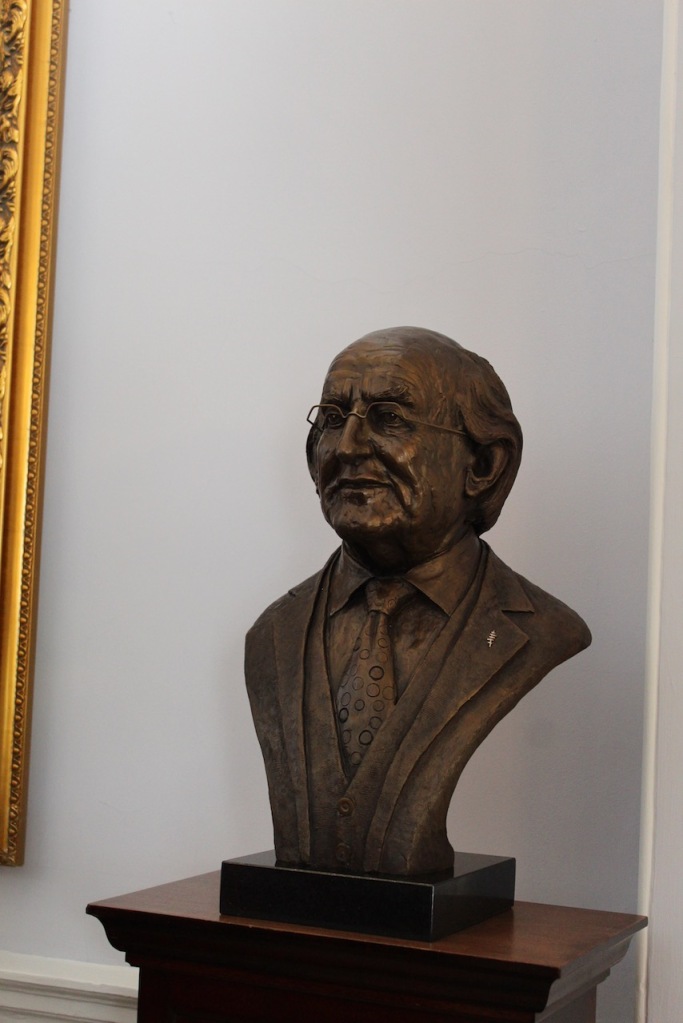

The State Corridor, also called the Lafranchini Corridor, leads from the Entrance Hall past the State Reception Room. This corridor was originally part of the orchestra pit for the adjoining ballroom. It was created as a corridor in the 1950s. One side of the corridor is lined with bronze busts of Irish Presidents mounted on marble columns and the other side features stucco panels showing classical figures. These too are casts taken from Riverstown House.

The State corridor also has a fireplace by 18th century Italian craftsman, Bossi, whose family knew the secret of how to colour marble.

Later additions to the gardens were carried out by Ninian Niven, who designed Iveagh Gardens in Dublin. The gardens contain many Victorian features including ceremonial trees, an arboretum, wilderness, pleasure grounds, avenues, walks, ornamental lakes and a walled garden, which contains a Turner peach house and which grows the food and flowers organically.

© Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com

[1] https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/aras-an-uachtarain/

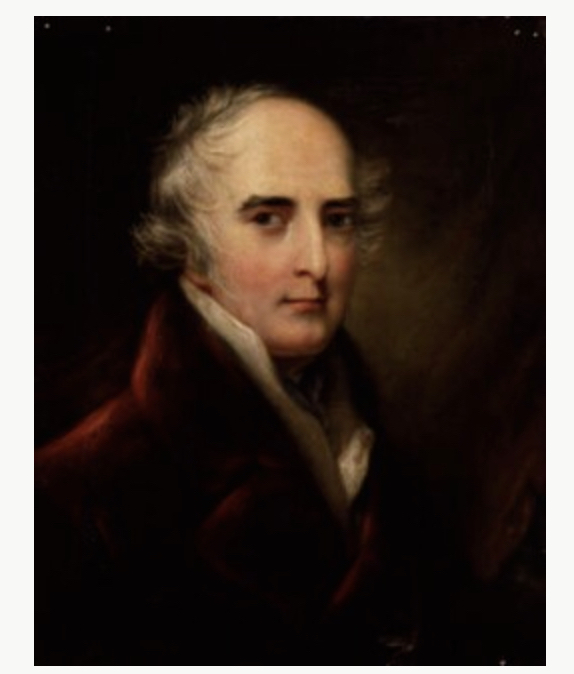

Some of the Viceroys and Vicereines who lived there may include (portraits below are from the 2021 exhibition of Vicereines that took place in Dublin Castle): William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck the 3rd Duke of Portland and his wife Dorothy (Viceroy 1782), George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 11st Marquess of Buckingham (Viceroy 1782), Charles Manners the 4th Duke of Rutland (1754-1787), Viceroy 1784-87, and his wife Mary Isabella, Charles Lennox the 4th Duke of Richmond and his wife Charlotte (Viceroy 1807-1813), Hugh Percy 3rd Duke of Northumberland and his wife Charlotte Florentia (Viceroy 1829-30), Constantine Henry Phipps 1st Marquess of Normanby and his wife Maria Phipps (Viceroy 1835-39), James Hamilton 1st Duke of Abercorn and his wife Louisa (Viceroy 1866-68 and 1874-76), Thomas de Grey, 2nd Earl de Grey, 3rd Baron Grantham, 6th Baron Lucas and his wife Henrietta Cole from Florence Court, County Fermanagh (Viceroy 1841-1844), Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 6th Marquess of Londonderry and his wife Theresa (Viceroy 1886-89), John Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer (Viceroy 1868-74 and 1882-5), John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair (Viceroy 1886 and 1905-1915)and Ivor Guest, 1st Viscount Wimborne (Viceroy 1915-1918).