In the past, in August 2016, I visited Huntington Castle in Clonegal, County Carlow.

www.huntingtoncastle.com

Open dates in 2024, but check website as closed for special events:

Castle Tours:

Open – February, March & April Saturdays & Sundays 1pm, 2pm & 3pm

Open – May, June, July, August & September Daily 1pm, 2pm, 3pm & 4pm

Open – October, November & December

Saturdays & Sundays 1pm, 2pm & 3pm

Fee: house/garden, adult €12.95, garden €6.50, OAP/student, house/garden €12, garden €6, child, house/garden €6.50, garden €3.50, group and family discounts available

2024 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2024 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

It’s magical! And note that you can stay at this castle – see their website! [1]

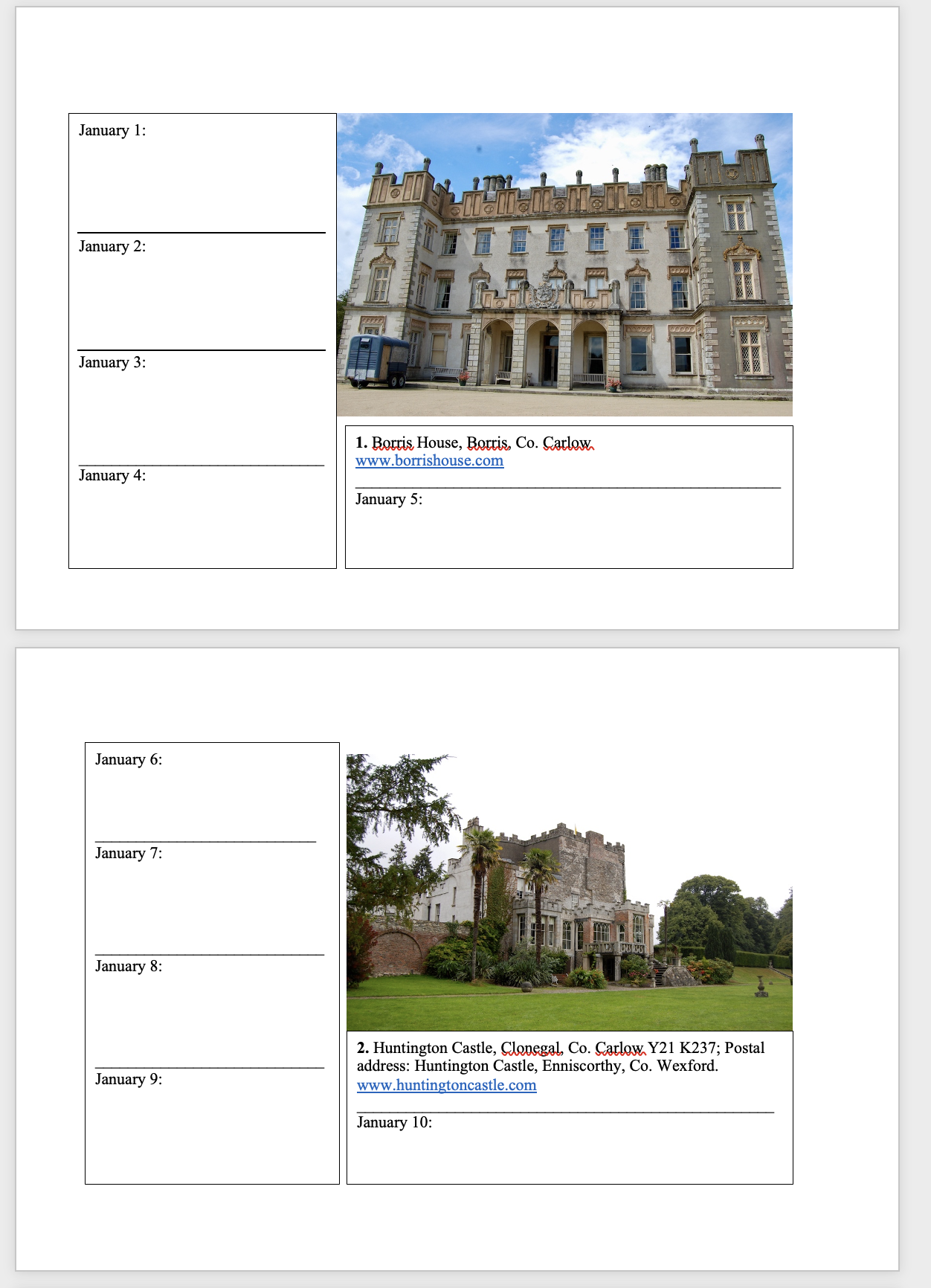

Huntington Castle stands in the valley of the River Derry, a tributary of the River Slaney, on the borders of Counties Carlow and Wexford, near the village of Clonegal. Built in 1625, it is the ancient seat of the Esmonde family, and is presently lived in by the Durdin-Robertsons. It passed into the Durdin family from the Esmonde family by marriage in the nineteenth century, so actually still belongs to the original family. It was built as a garrison on the strategically important Dublin-Wexford route, on the site of a 14th century stronghold and abbey, to protect a pass in the Blackstairs Mountains. It was also a coach stop on the Dublin travel route to Wexford. There was a brewery and a distillery in the area at the time. After fifty years, the soldiers moved out and the family began to convert it into a family home. [2]

A History of the house and its residents

The castle website tells us that the Esmondes (note that I have found the name spelled as both ‘Esmond’ and ‘Edmonde’) moved to Ireland in 1192 and were involved in building other castles such as Duncannon Fort in Wexford and Johnstown Castle in Wexford (see my entry for places to visit in County Wexford). There is a chapter on the Esmonds of Ballynastragh in The Wexford Gentry by Art Kavanagh and Rory Murphy. They tell us that it is believed that Geoffrey de Estmont was one of the thirty knights who accompanied Robert FitzStephen to Ireland in 1169 when the latter lead the advance force that landed at Bannow that year. Sir Geoffrey built a motte and baily at Lymbrick in the Barony of Forth in Wexford, and his son Sir Maurice built a castle on the same site. After Maurice’s death in 1225 the castle was abandoned and his son John built a castle on a new site which was called Johnstown Castle. John died in 1261. [3] After the Cromwellian Confiscations, since the Johnstown Esmondes were Catholic, their lands were granted to Colonel Overstreet, and later came into the possession of the Grogan family. The Ballynastragh/Lymbrick lands were also confiscated and the Ballytramont property was granted to the Duke of Ablemarle (General Monck). [see my entry about Johnstown Castle in Places to visit and stay in County Wexford]. They later regained Ballynastragh.

A descendant, Laurence Esmonde (about 1570-1645) converted to Anglicanism and served in the armies of British Queen Elizabeth I and then James I.

He fought in the Dutch Wars against Spain, and later, in 1599, he commanded 150 foot soldiers in the Nine Years War, the battle led by an Irish alliance led mainly by Hugh O’Neill 2nd Earl of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O’Donnell against the British rule in Ireland.

In 1602 he built a castle and a church at Luimneach near the modern village of Killinerin and near Ballynastragh, which he named Lymbrick after the original Norman motte and bailey in the Barony of Forth. [see 3]

He governed the fort of Duncannon from 1606-1646. In reward for his services, he was raised to the peerage in 1622 as Baron of Lymbrick in County Wexford and it seems that a few years after receiving this honour he built the core of the present Huntington Castle on the site of an earlier military keep. He built a three-storey fortified tower house, which forms the front facing down the avenue, according to Mark Bence-Jones in A Guide to Irish Country Houses. [4]

This original tower-house is made of rough-hewn granite. In her discussion of marriage in Making Ireland English, Jane Ohlmeyer writes that for the Irish, legitimacy of children didn’t determine inheritance, and so attitudes toward marriage, including cohabitation and desertion, were very different than in England. She writes that the first Baron Esmonde behaved in a way reminiscent of medieval Gaelic practices when he repudiated his first wife and remarried without a formal divorce. Laurence met Ailish, the sister of Morrough O’Flaherty (note that Turtle Bunbury tells us that she was a granddaughter of the pirate queen Grace O’Malley!) on one of his expeditions to Ulster, and married her. However, after the birth of their son, Thomas, she returned to her family, fearing that her son would be raised as a Protestant. [5]

Esmonde went on to marry Elizabeth Butler, a granddaughter of the ninth earl of Ormond (daughter of Walter Butler, and she was already twice widowed). He had no children by his second marriage and despite acknowledging Thomas to be his son, he did not admit that his first marriage was lawful and consequently had no official heir and his title Baron of Lymbrick became extinct after his death.

Baron Esmonde died after a siege of Duncannon fort by General Thomas Preston, 1st Viscount Tara, of the Confederates, who considered Esmonde a defender of the Parliamentarians (i.e. Oliver Cromwell’s men, the “roundheads”). Although his son did not inherit his title, he did inherit his property. [6]

After Lawrence’s death the Huntington estate and castle was occupied as a military station by Dudley Colclough from 1649-1674. [see 3]

Lawrence’s son Thomas Esmonde started his military career as an officer in the continental army of King Charles I. For his service at the siege of La Rochelle he was made a baronet of Ireland while his father still lived, and became 1st Baronet Esmonde of Ballynastragh, County Wexford, in 1629. He did not return to Ireland, however, until 1646 after his father’s death. He joined the rebels, the Confederate forces, who were fighting against the British forts which his father held. Taking after his mother, he was a resolute Catholic.

He married well, into other prominent Catholic families: first to a daughter of the Lord of Decies, Ellice Fitzgerald. She was the widow of another Catholic, Thomas Butler, 2nd Baron Caher, and with him had one daughter, Margaret, who had married Edmond Butler, 3rd/13th Baron Dunboyne a couple of years before her mother remarried in around 1629. Thomas and Ellice had two sons. Ellice died in 1644/45 and Thomas married secondly Joanne, a daughter of Walter Butler 11th Earl of Ormond. She too had been married before, to George Bagenal who built Dunleckney Manor in County Carlow. Her sons by Bagenal were also prominent Confederate Colonels. She was also the widow of Theobald Purcell of Loughmoe, County Tipperary. We came across the Purcells of Loughmoe on our visit to Ballysallagh in County Kilkenny (see my entry).

Thomas served as Member of Parliament for Enniscorthy, County Wexford from 1641 to 1642, during the reign of King James II.

His son Laurence succeeded as 2nd Baronet, and reoccupied Huntington Castle in 1682. [see 3]

Laurence made additions to Huntington Castle around 1680, and named it “Huntington” after the Esmonde’s “ancestral pile” in Lincolnshire, England [7]. He is probably responsible for some of the formal garden planting. The Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne discusses this garden in another blog entry [8]. He tells us that the yew walk, which stretches 130 yards, dates from the time of the Franciscan friary in the Middle Ages!

Laurence 2nd Baronet married Lucia Butler, daughter of another Colonel who fought in the 1641 uprising, Richard Butler (d. 1701) of Garryricken. Their daughter Frances married Morgan Kavanagh, “The MacMorrough” of the powerful Irish Kavanagh family.

The 3rd Baronet, another Laurence, served for a while in the French army.

A wing was constructed by yet another Sir Laurence, 4th Baronet, in 1720. The castle, as you can see, is very higgeldy piggedly, reflecting the history of its additions. The 4th Baronet had no heir so his brother John became the 5th Baronet. He had a daughter, Helen, who married Richard Durdin of Shanagarry, County Cork. The went out to the United States and founded Huntington, Pennsylvania. He had no sons, and died before his brother, Walter, who became the 6th Baronet. Walter married Joan Butler, daughter of Theobald, 4th Baron Caher. Walter and Joan also had no sons, only daughters.

In The Wexford Gentry we are told that the widow of the 6th Baronet was left in “straitened circumstances” after her husband Walter died in 1767, and sold the estate of Huntington to Sir James Leslie (1704-1770), the Church of Ireland Bishop of Limerick, in 1751. He was from the Tarbert House branch of the Leslie family in County Kerry. Huntington remained in his family until 1825 when it was leased to Alexander Durdin (1821-1892) and later bought by his descendants. [see 3, p. 106].

The line of inheritance looks very convoluted. I have consulted Burke’s Peerage. John Durdin migrated from England to Cork in around 1639. His descendant Alexander Durdin, born in 1712, of Shanagarry, County Cork, married four times! His second wife, Mary Duncan of Kilmoon House, County Meath, died shortly after giving birth to her son Richard, born in 1747. Alexander then married Anne née Vaux, widow of the grandson of William Penn the founder of Pennsylvania. Finally, he married Barbara St. Leger, with whom he had seven more sons and several daughters.

It was Alexander’s son Richard who married Helen Esmonde, daughter of the 4th Baronet, according to Burke’s Peerage. Richard then married Frances Esmonde, daughter of the 7th Baronet.

The 6th Baronet had only daughter so the title went to a cousin. This cousin was a descendant of Thomas Esmonde 1st Baronet of Ballynastragh, Thomas’s son James. James had a son Laurence (1670-1760), and it was his son, James (1701-1767) who became the 7th Baronet of Ballynastragh. It was his daughter Frances who married Richard Durdin of Huntington Pennsylvania, who had been previously married to Helen Esmonde.

Despite his two marriages, Richard had no son. His brother William Leader Durdin (1778-1849) married Mary Anne Drury of Ballinderry, County Wicklow and it was their son Alexander (1821-1892) who either inherited Huntington, or at least, according to The Wexford Gentry, leased and later purchased Huntington, the home of his ancestors.

Alexander also had only daughters. In 1880, his daughter Helen married Herbert Robertson, Baron Strathloch (a Scots feudal barony) and MP for a London borough. She inherited Huntington Castle when her father died. Together they made a number of late Victorian additions at the rear of the castle while their professional architect son, Manning Durdin-Robertson, an early devotee of concrete, carried out yet further alterations in the 1920s. Manning also created W. B. Yeats’s grave, and social housing in Dublin.

There is an irregular two storey range with castellated battlements and a curved bow and battlemented gable in front of the earlier building, which rises above them. The front battlemented range was added in the mid 1890s.

The older part of the castle includes a full height semicircular tower. Inside, when one enters through the portico facing onto the stable yard, one can see the outside of this full height semicircular tower, curving into the room to one’s right hand side, where there is even a little stone window set in the curved wall, and the round tower bulges into the stairway hall, clad with timber and covered in armour.

We entered the castle through a door in the battlemented porticon next to the double height bow facing onto the stableyard and courtyard. Inside the portico are statues which may have been from the Abbey – I forgot to ask our tour guide, as there was just so much to see and learn about.

We were not allowed to take photos inside, except for in the basement, but you can see some pictures on the official website [1] and also on the wonderful blog of the Irish Aesthete [10].

There were wonderful old treasures in the house including armour chest protections in the hallway along the stairs, which was one of the first things to catch my attention as we entered. Our guide let us hold it – it was terribly heavy, and so a soldier must have been weighed down by his armour – wearing chain mail underneath his shielding armour. The chest protection piece we held was made of cast iron! She showed us the “proof mark” on the inside. Cast iron could shatter, our guide told us, so a piece of armour would be tested, leaving a little hole, which proved that it would not shatter when worn and hit by a projectile or sword. This piece dates all the way back to Oliver Cromwell’s time!

To the right when one enters is a room full of animal heads and weapons. There is a huge bison head from India and a black buck, and a sawfish from the Caribbean. A gharial crocodile hanging on the wall was killed by Nora Parsons at the age of seventeen in India! There is also the shell of an armadillo. The room also has a lovely wooden chimneypiece and there is another in the hallway, which has a Tudor style stucco ceiling. We went up a narrow stairway lined as Bence-Jones describes “with wainscot or half-timbered studding.”

Manning Durdin-Robertson married Nora Kathleen Parsons, from Birr Castle. She wrote The Crowned Harp. Memories of the Last Years of the Crown in Ireland, an important memorial of the last years of English rule in Ireland [11]. I ordered a copy of the book from my local library! It’s a lovely book and an enjoyable rather “chatty” read. She writes a bit about her heritage, which you can see in my entry on another section 482 castle, Birr Castle. She tells us about life at the time, which seems to have been very sociable! She writes a great description of social rank:

The hierarchy of Irish social order was not defined, it did not need to be, it was deeply implicit. In England the nobility were fewer and markedly more important than over here and they were seated in the mansions considered appropriate….

The top social rows were then too well-known and accepted to be written down but, because a new generation may be interested and amused, I will have a shot at defining an order so unreal and preposterous as to be like theatricals in fancy dress. Although breeding was essential it still had to be buttressed by money.

Row A: peers who were Lord or Deputy Lieutenants, High Sheriffs and Knights of St. Patrick. If married adequately their entrenchment was secure and their sons joined the Guards, the 10th Hussars or the R.N. [Royal Navy, I assume]

Row B: Other peers with smaller seats, ditto baronets, solvent country gentry and young sons of Row A, (sons Green Jackets, Highland regiments, certain cavalry, gunners and R.N.).

Row A used them for marrying their younger children.

Row C: Less solvent country gentry, who could only allow their sons about £100 a year. These joined the Irish Regiments which were cheap; or transferred to the Indian army. They were recognised and respected by A and B and belonged to the Kildare Street Club.

Row D: Loyal professional people, gentlemen professional farmers, trade, large retail or small wholesale, they could often afford more expensive Regiments than Row C managed. Such rarely cohabited with Rows A and B but formed useful cannon fodder at Protestant Bazaars and could, if they were really liked, achieve Kildare Street.

Absurd and irritating as it may seem today, this social hierarchy dominated our acceptances.

I had the benefit of always meeting a social cross section by playing a good deal of match tennis…. The top Rows rarely joined clubs and their play suffered….There were perhaps a dozen (also very loyal) Roman Catholic families who qualified for the first two Rows; many more, equally loyal but less distinguished, moved freely with the last two.

Amongst these “Row A” Roman Catholics were the Kenmares, living in a long gracious house at Killarney. Like Bantry House, in an equally lovely situation.…”

There are some notable structures inside the building, as Robert O’Byrne notes. “The drawing room has 18th century classical plaster panelled walls beneath a 19th century Perpendicular-Gothic ceiling. Some passages on the ground floor retain their original oak panelling, a number of bedrooms above being panelled in painted pine. The dining room has an immense granite chimneypiece bearing the date 1625, while those in other rooms are clearly from a century later.” [10]

The dining room, the original hall of the castle, is hung with Bedouin tents, brought back from Tunisia in the 1870s by Herbert Robertson, Helen Durdin’s husband. The large stone fireplace has the date stone 1625, and a stained glass window traces out the Esmonde and Durdin genealogy. We know that the room is very old by the thickness of the walls. The room has an Elizabethan ceiling, and portraits of family members hang on the walls. You can see a photograph of the room on the Castle Tours page of the website. There is a portrait of Barbara St. Leger, from Doneraile in Cork, who married Alexander Durdin (1712-1807), the one who also married the two Esmonde daughters. It is said that Barbara wore a set of keys at her waist, and that sometimes ghostly jingling can be heard in the castle.

Next to the dining room is a ladies drawing room with white panelled walls and a stucco ceiling with Gothic drop decoration and compartments. I think it was in this room the guide told us that the panelling is made of plaster, created to look like wood panelling. You can see some photographs of these rooms on the castle’s facebook page. The ceiling may seem low for an elegant room but we must remember that it originally housed a barracks! This room also is part of the original structure – the doorway into the next room shows how thick the wall is – about the length of two arms.

Another drawing room is hung with tapestry, which would have kept the residents a bit warmer in winter. There are beautiful stuccoed ceilings, which you can see on the website, and a deep bay window with Gothic arches in the bars of the window.

Huntington was one of the first country houses in Ireland to have electricity, and in order to satisfy local interest a light was kept burning on the front lawn so that the curious could come up and inspect it.

I loved the light and plant filled conservatory area, with a childlike drawing on one wall. The glass ceiling is draped in grape vines. The picture is of the estate, drawn by the four children of the house in 1928, Olivia Durdin-Robertson and her brother Derry and sister Barbara, children of Manning and Nora. I loved the pictures of the children themselves swimming in the river, wearing little swimming hats! The picture even has the telephone wires in it. The conservatory area is part of an addition on the back of the castle, added around 1860.

The conservatory is in the brick and battlemented addition to one side of the castle. From the formal gardens to the side of the castle a different vantage shows more of the castle and one can see the original tower house, and the additions.

The conservatory contains a vine that is a cutting taken in the 1860s of a great vine in Hampton Court.

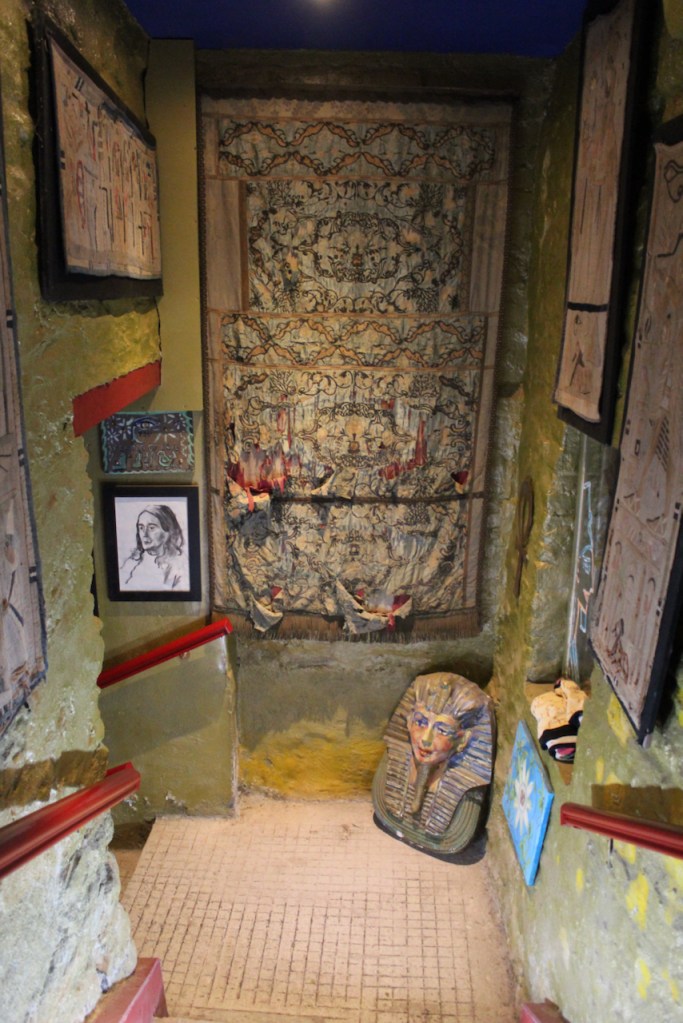

We were allowed to take photos in the basement, which used to house dungeons, and now holds the “Temple of Isis.” It also contains a well, which was the reason the castle was situated on this spot.

In the 1970s two of the four children of Manning Durdin-Robertson, the writer and mystic Olivia Durdin-Robertson, who was a friend of W.B. Yeats and A.E. Moore, and her brother Laurence (nicknamed Derry), and his wife Bobby, converted the undercroft into a temple to the Egyptian Goddess Isis, founding a new religion. In 1976 the temple became the foundation centre for the Fellowship of Isis [11]. I love the notion of a religion that celebrates the earthy aspects of womanhood, and I purchased a copy of Olivia Durdin-Robertson’s book in the coffee shop. The religion takes symbols from Egyptian religion, as you can see in my photos of this marvellous space:

Turtle Bunbury has a video of the Fellowship of Isis on his website [12]! You can get a flavour of what their rituals were like initially. Perhaps they are similar today. The religion celebrates the Divine Feminine.

After a tour of the castle, we then went to the back garden, coming out from the basement by a door under the stone balcony. According to its website:

“The Gardens were mainly laid out in the 1680s by the Esmondes. They feature impressive formal plantings and layouts including the Italian style ‘Parterre’ or formal gardens, as well the French lime Avenue (planted in 1680). The world famous yew walk is a significant feature which is thought to date to over 500 years old and should not be missed.

“Later plantings resulted in Huntington gaining a number of Champion trees including more than ten National Champions. The gardens also feature early water features such as stew ponds and an ornamental lake as well as plenty to see in the greenhouse and lots of unusual and exotic plants and shrubs.“”Later plantings resulted in Huntington gaining a number of Champion trees including more than ten National Champions. The gardens also feature early water features such as stew ponds and an ornamental lake as well as plenty to see in the greenhouse and lots of unusual and exotic plants and shrubs.“

The “stew ponds” would have held fish that could be caught for dinner.

After the garden, we needed a rest in the Cafe.

I was also thrilled by the hens who roamed the yard and even tried to enter the cafe:

There is space next to the cafe that can be rented out for events:

A few plants were for sale in the yard. A shop off the cafe sells local made craft, pottery, and books. The stables and farmyard buildings are kept in good condition and buzzed with with the business of upkeep of the house and gardens.

[1] https://www.huntingtoncastle.com/

[2] The website http://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Huntington%20Castle says it was built on the site of a 14th century stronghold and abbey, whereas the Irish Aesthete says it was built on the site of a 13th century Franciscan monastery.

[3] Kavanagh, Art and Rory Murphy, The Wexford Gentry. Published by Irish Family Names, Bunclody, Co Wexford, Ireland, 1994.

[4] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[5] p. 171, Ohlmeyer, Jane. Making Ireland English. The Irish Aristocracy in the Seventeenth Century. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2012. See also pages 43, 273, 444 and 451.

[6] Dunlop, Robert. ‘Edmonde, Laurence.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition volume 18, accessed February 2020. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Esmonde,_Laurence_(DNB00)

[7] http://www.turtlebunbury.com/history/history_houses/hist_hse_huntington.html

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/11/14/light-and-shade/

[9] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[10] https://theirishaesthete.com/2017/01/23/huntington/

[11] Robertson, Nora. The Crowned Harp. Memories of the Last Years of the Crown in Ireland. published by Allen Figgis & Co. Ltd., Dublin, 1960.

[12] http://www.turtlebunbury.com/history/history_houses/hist_hse_huntington.html

http://www.fellowshipofisis.com/

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00