Open dates in 2026: Jan 5-9, Feb 23-28, Mar 1-9, May 15-24, June 29-30, July 1-10, Aug 8-25,

10am-2pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP €8, student €5 with student card, child €5 under 12 years, school groups €3 per person

The charming Kildrought house is located on the main street of the village of Celbridge. I had never been to Celbridge village despite many visits to Castletown House, which has an entry from one end of the village. Kildrought house was developed at the same time as Castletown house, if not a little earlier, as Kildrought was built for Robert Baillie, who was, as well as being a leading tapestry manufacturer, a land agent for William Conolly (1662-1729) who built Castletown.

Up the road another house had been recently built, in 1703, Celbridge Abbey for Bartholomew Van Homreigh (also spelled Homrigh. Celbridge Abbey is now unfortunately in a sad state of disrepair). Van Homreigh was commissary-general to William III’s army, and he became Lord Mayor of Dublin. He was the father of a friend of Jonathan Swift, Esther Van Homreigh, whom he called “Vanessa.”

The Kildare local history website tells us that the area was historically named Kildrought, and only changed the name to Cell-bridge, shortened to Celbridge, in 1714. [2] The River Liffey runs parallel to the main road of Celbridge.

William Conolly purchased land which had been owned by Thomas Dongan (1634-1715), 2nd Earl of Limerick, in 1709. Dongan’s estate has been confiscated as he was a Jacobite supporter of James II (he became first governor of the duke of York’s province of New York! The Earldom ended at his death). His mother was the daughter of William Talbot, 1st Baronet of Carton (see my entry about Carton, County Kildare, under Places to stay in County Kildare).

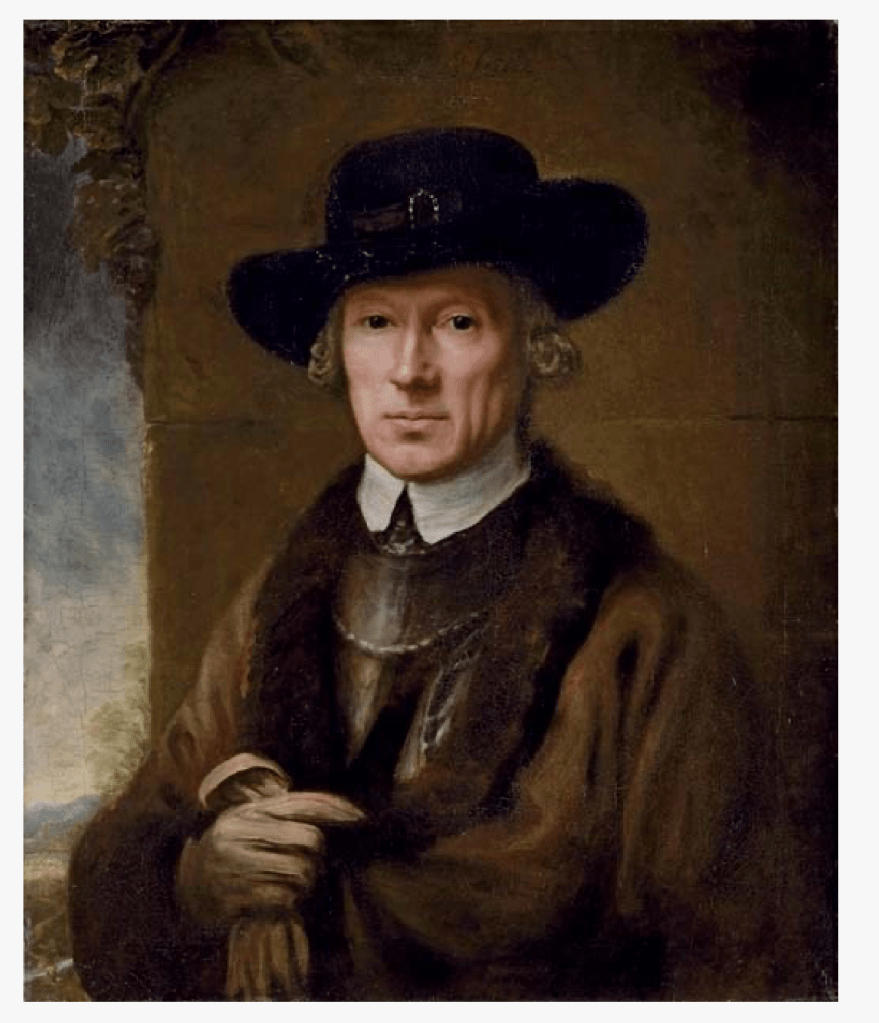

Both Conolly and Baillie had property on Capel Street in Dublin, before moving to Celbridge. Conolly’s house was on the corner of Capel Street and Little Britain Street and was demolished around 1770. [3] William Conolly started from relatively humble beginnings in County Donegal. He trained as an attorney and grew wealthy by making astute land investments.

Kildrought house was built around 1720. Building at Castletown began in 1722.

Robert Baillie brought tapestry-making to Ireland, bringing Flemish weavers to Ireland. The tapestries in the House of Lords in Parliament, which is now part of the Bank of Ireland on College Green in Dublin, features tapestries made by Baillie’s workers. June, Kildrought’s owner, told us that he was an “upholder,” or what we now call an “upholsterer,” but it really meant at the time an interior designer. Baillie obtained the commission through his connection with Conolly. It was Conolly who oversaw the construction of the new Parliament building on College Green, the first purpose built two chamber parliament building in the world. (see [2])

For more on the Irish Houses of Parliament, see Robert O’Byrne’s entry, https://theirishaesthete.com/2024/07/08/bank-of-ireland/

The design of Kildrought is attributed to Thomas Burgh (1670-1730), Surveyor General of Ireland, who also designed the Library of Trinity College, Dublin (the building that contains The Long Room).

The house is two storeys to the front elevation and three to the rear (including a basement) and is five bays wide with a central entryway on the front facade. There is a pediment on the front facade and the arched window stretches up into the pediment. The National Inventory tells us that the use of early red brick (now painted yellow) to the dressings is an attractive feature of the composition and reveals a high quality of craftsmanship in the locality, notably to the profiled courses to the eaves. [4] The house is lime plastered, and has a two storey lean-to to one side with a pretty arched window, and a sundial installed by June, the current owner.

Stone steps lead up to the front door from the forecourt, and one walks over a bridgeway over the basement level. Over the front door is a decorative fanlight.

The current owners purchased the house in 1985, the first time it came on the market in 265 years, as before that, it was a leasehold property on the estate of William Conolly (1662-1729).

Robert Baillie married Susanna Antrobus, a cousin of Ester Van Homrigh. Jimmy O’Toole tells us in his book The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! that the commission for the House of Lords did not work out well for Robert Baillie. [6] He engaged the services of painter Johann Van der Hagen (we saw his work in Beaulieu in County Louth, see my entry) and the weaver John Van Beaver. Baillie understood that he would also be commissioned to furnish the houses of Parliament. However, he did not receive the commission for the furniture. Perhaps it was this misunderstanding that led to Baillie’s financial decline, leading him to sell Kildrought in 1749. This often seems to be the way with tradesmen working for aristocrats. Work was undertaken with expectation of further work and commissions. Businessmen had to take a gamble on the hope of future work, investing often beyond their means to supply quality work for the initial commission. If this initial commission didn’t lead to further work, it could lead to ruin.

Unfortunately the same worked for the aristocrats themselves. They ordered and obtained food, clothing, furniture from merchants and tradesmen, on credit. They built up debt, and were sometimes unable to pay off their debts. Debts were passed on after death to descendants so that one could inherit not just land and goods but debts.

The Baillie family moved to County Carlow. Robert’s son Arthur (b. 1726) married the daughter of a neighbour and land agent of William Conolly, Williamina Katherina Finey. Arthur purchased Sherwood Park in County Carlow. He passed the house then to his brother Richard (1726-1804) who fought with Wolfe at Quebec.

Robert’s son William (1723-1810) became a well-known engraver.

From 1782 Kildrought became the home of Owen Bagnall’s Celbridge Academy, until 1814, where students included future bishop John Jebb and the sons of George Napier and Sarah Lennox (her sister married Thomas Conolly, nephew and heir of William Conolly).

From 1818-40 it served as a fever hospital, then a vicarage, and had a few other occupants before the current owners.

The building was restored 1985-95 by the present owners.

The current owners have sought to restore the house authentically to what would have been the original condition. The front hall has decorative dentil cornice original to the house, and niches on either side of the front door, which Andrew Tierney tells us in his book The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster were uncovered during the restoration in the 1990s. Their keystones were copied from Castletown. [5] The front door has shutters for the glass top half of the door. The hall is a perfect cube.

The Stuarts had all of the wood panelling done in the house. The doors with shouldered architraves are original to the house.

The upstairs had been altered, and the Stuarts brought the house back to something more like its original configuration. At the top of the stairs is the arched window which we saw from the front.

The drawing room is the width of the main house, and has beautiful views over the back garden, and a fireplace at either end. The room had been divided into two but the Stuarts took down the central wall to create the spacious bright salon, the Great Parlour.

The kitchen and another sitting room and informal dining room are downstairs in the basement level of the house, which is the ground level at the back of the house.

The terraced garden at the rear of the house goes down to the Liffey and was also created in 1720. The National Inventory points out that the formal gardens to the south-east are of particular interest in terms of their landscape design qualities, and reflect the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century fashions for formal landscaping. They are splendid, and we were lucky to have a superb sunny day which showed them off to best effect.

The current owners sought to recreate a formal garden and to restrict plantings only to those known to be introduced before 1720.

The side wing was added around 1747.

There are two more buildings on the property. One has been converted to extra accommodation, described by the National Inventory as a three-bay single-storey curvilinear gable-fronted outbuilding with attic, c.1720, to north-west with seven-bay single-storey side elevation to north-east.

There is also a three-bay single-storey flat-roofed red brick summer house, built around 1840, to the south.

The Stuarts have created a wonderful home and every inch of the property seems to be well-kept and beautiful!

[1] https://theirishaesthete.com/tag/kildrought-house/

[2] http://kildarelocalhistory.ie/celbridge See also my entry on Castletown House in my entry for OPW properties in Kildare, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/21/office-of-public-works-properties-leinster-carlow-kildare-kilkenny/

[3] p. xiii, Jennings, Marie-Louise and Gabrielle M. Ashford (eds.), The Letters of Katherine Conolly, 1707-1747. Irish Manuscripts Commission 2018. The editors reference TCD, MS 3974/121-125; Capel Street and environs, draft architectural conservation area (Dublin City Council) and Olwyn James, Capel Street, a study of the past, a vision of the future (Dublin, 2001), pp. 9, 13, 15-17.

[5] p. 225, Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[6] p. 19. O’Toole, Jimmy. The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! Published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com