Farmleigh House, Phoenix Park, Dublin

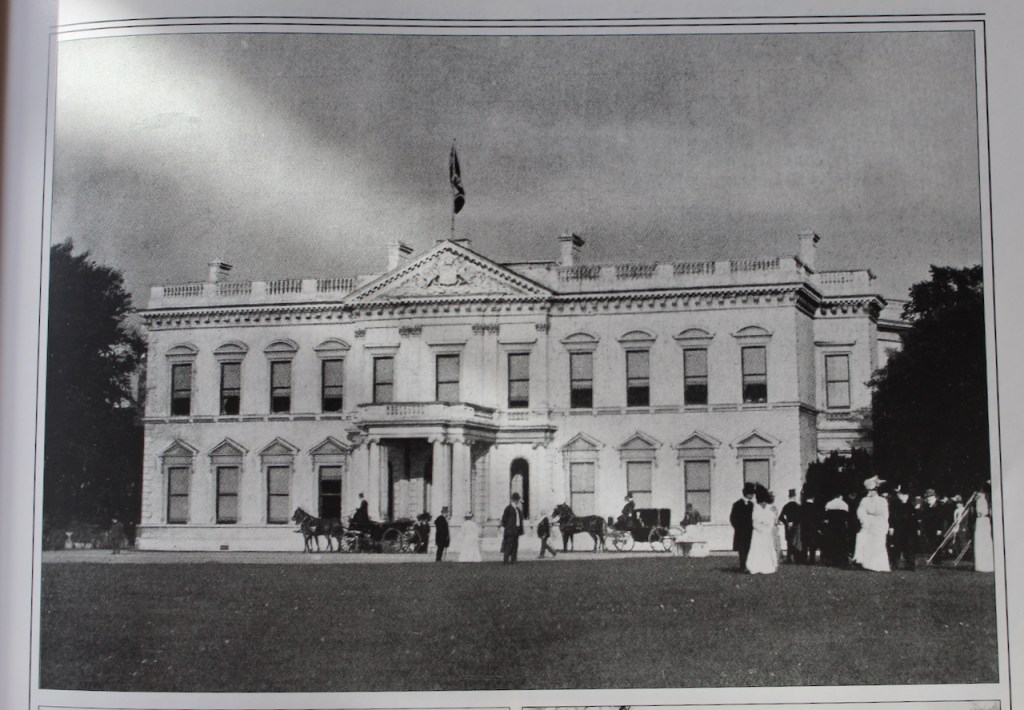

Farmleigh House is part of a 78-acre estate inside Dublin’s Phoenix Park. The government bought it in June 1999 to provide accommodation for high-level meetings and visiting guests of the nation. The rest of the time it is maintained by the Office of Public Works and is open to the public for tours.

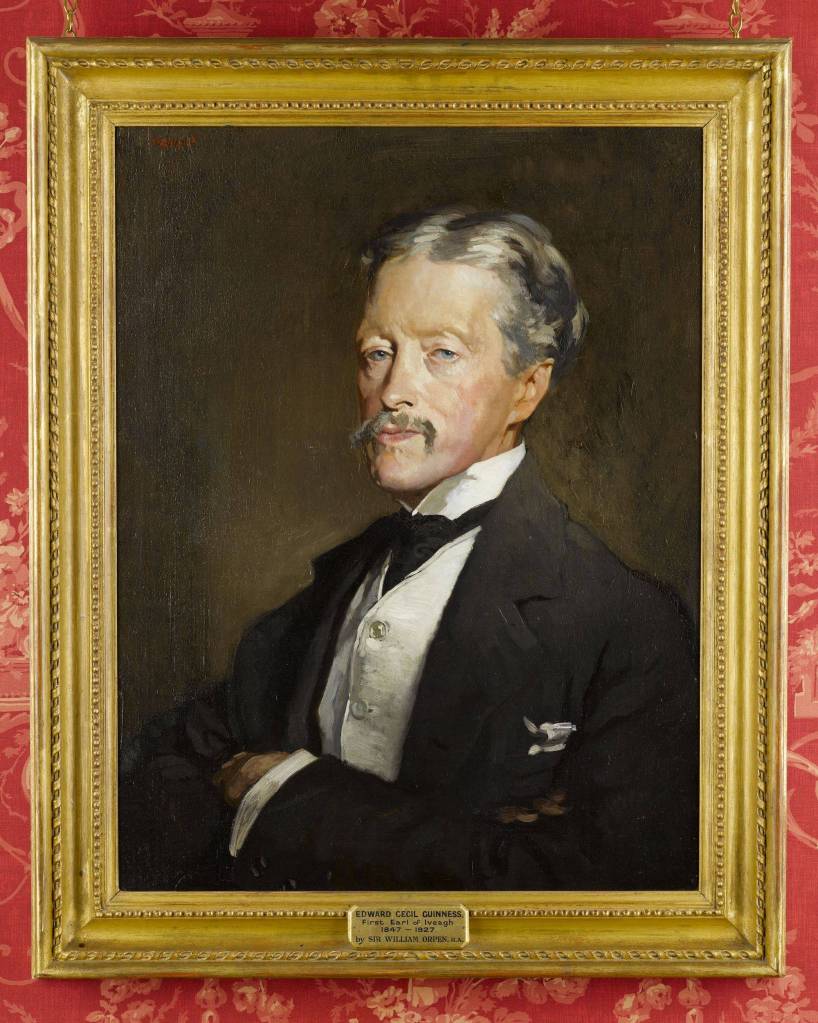

Farmleigh was originally a two storey Georgian house, belonging to the Coote family and the Trenches, then bought by Edward Cecil Guinness (1847-1927) in 1873, a great grandson of brewery owner Arthur Guinness, at the time of his marriage to his cousin Adelaide Guinness.

Farmleigh was built for the Trench family in 1752, according to a Dublin City Council website, Bridges of Dublin. Charles Trench built the walled garden. I am afraid I am unable to find more information about the Trenches of Farmleigh so I would appreciate any feedback about them.

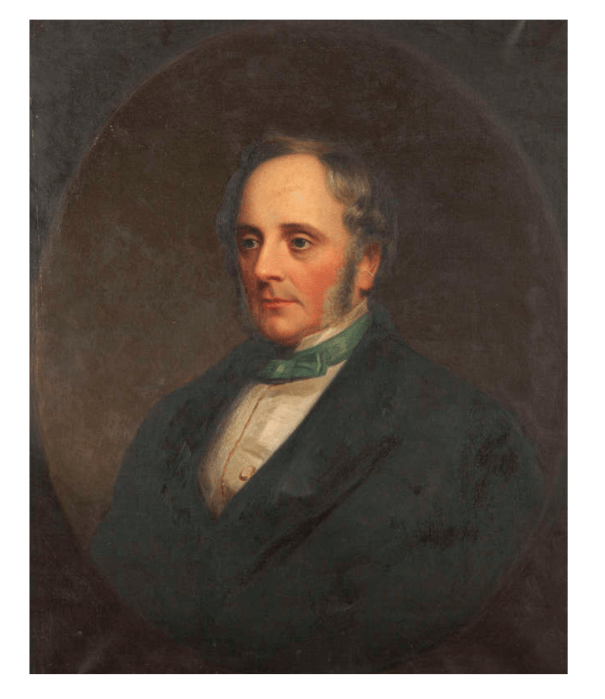

The Landed Estates database identifies John Chidley Coote (1816-1879) as a previous owner, the son of Charles Henry Carr Coote (1794-1864) 9th Baronet. John Chidley was from Ballyfin in County Laois, later and school and now a beautiful hotel. He married his neighbour Margaret Mary Pole Cosby from Stradbally Hall in County Laois (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/10/14/stradbally-hall-stradbally-co-laois/ ), daughter of Sydney Cosby (1807-1840). They had no children, and she went on to marry Charles Robert Piggott 3rd Baronet of Knapton, County Laois, after John Chidley’s death.

Edward Cecil Guinness enlarged the house, using designs first by James Franklin Fuller (1832-1925), who extended the house to the west, refurbished the existing house and added a third storey. Edward Cecil later engaged William Young (1843-1900), a young Scottish architect, who added the ballroom wing in 1896. Young also worked on the Guinness’s English country seat Elveden in Surrey and Edward Cecil’s house on St. Stephen’s Green. A conservatory was added adjoining the ballroom in 1901. Edward Cecil Guinness was created the 1st Earl of Iveagh in 1919.

From the website:

“Farmleigh is a unique representation of its heyday, the Edwardian period. Edward Cecil Guinness [(1847-1927) 1st Earl of Iveagh], great-grandson of Arthur Guinness (founder of the brewery), constructed Farmleigh around a smaller Georgian house in the 1880s. According to his tastes, the new building merged a variety of architectural styles.

“Many of the artworks and furnishings that Guinness collected remain in the house. There is a stunning collection of rare books and manuscripts in the library. The extensive pleasure-grounds contain wonderful Victorian and Edwardian ornamental features, with walled and sunken gardens and scenic lakeside walks. The estate also boasts a working farm with a herd of Kerry cows.” [1]

In the Dublin between the canals book by Christine Casey, part of the Buildings of Ireland series, she describes Farmleigh as a mediocre building. It is of three storeys with an extensive south facing front, rendered with a pediment and Corinthian Portland stone portico to the two advanced central bays and central canted bows to the flanking five-bay ranges. The five bays on the right of the porch correspond to the eighteenth century house, of which one interior survives, she tells us.

One is not allowed to take photographs inside the house but you can see pictures of the house and take an online tour on the website. It operates as the official residence for guests of the Irish state, which is why photography is not allowed inside.

The website tells us:

“With the addition of a new Conservatory adjoining the Ballroom in 1901, and increased planting of broadleaves and exotics in the gardens, Farmleigh had, by the early years of the twentieth century, all the requisites for gracious living and stylish entertainment. Its great charm lies in the eclecticism of its interior decoration ranging from the classical style to Jacobean, Louis XV, Louis XVI and Georgian.

“Farmleigh was purchased from the Guinness family by the Irish Government in 1999 for €29.2m. The house has been carefully refurbished by the Office of Public Works as the premier accommodation for visiting dignitaries and guests of the nation, for high level Government meetings, and for public enjoyment.” [2]

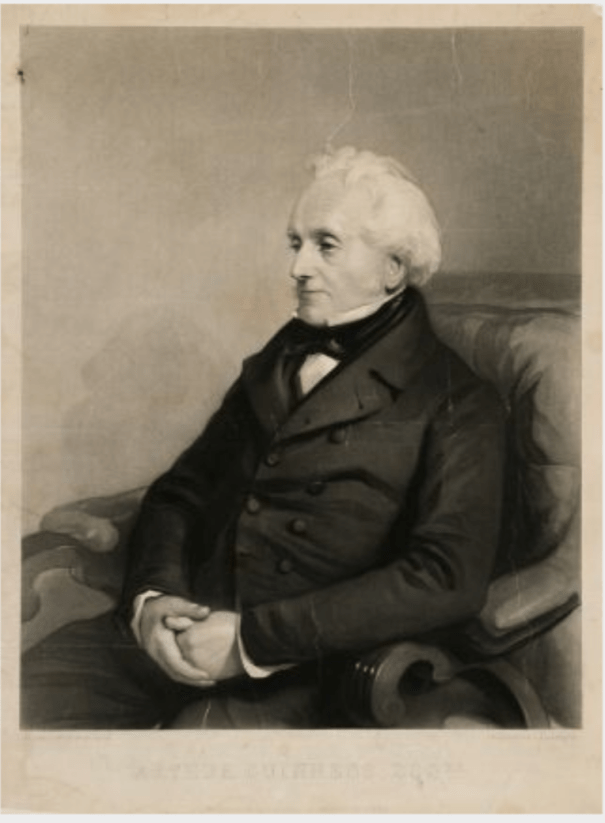

Edward Cecil Guinness was the son of Benjamin Lee Guinness (1798-1868), who purchased Ashford Castle, County Galway, in 1855. The castle had been a shooting lodge belonging to Lord Oranmore and Browne. In 1867 Benjamin Lee Guinness was created 1st Baronet of Ashford Castle in thanks for his restoration of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin at his own expense. His father had lived in St. Anne’s Park in Clontarf, a house unfortunately no longer in existence.

Edward Cecil’s older brother Arthur Edward (1840-1915), like his father, held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) (Conservative) for the City of Dublin. He succeeded as 2nd Baronet of Ashford Castle. He added to the residence at Ashford Castle and developed its grounds. He was created Baron Ardilaun of Ashford Castle in 1880. In 1871 he married Lady Olivia Charlotte White, daughter of the 3rd earl of Bantry. They had no children, and the Ardilaun barony became extinct after his death in Dublin on 20 January 1915.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us about Arthur Edward:

“As well as providing funding for the completion of the restoration of Marsh’s library, begun by his father, he also contributed to the rebuilding of the Coombe Hospital. As president of the Artisans’ Dwellings Company (in which he was a large shareholder), he took particular interest in improving working-class housing conditions, most notably in the areas around St Patrick’s cathedral. Perhaps his most notable legacy was financing the transformation of the twenty-two-acre St Stephen’s Green into a landscaped garden, which, through an act of parliament sponsored by Guinness, was presented to the Board of Works for the use of Dublin citizens. This generosity was marked by the erection of a bronze statue of him in the park, financed by public subscription in 1891. Another significant purchase of his was the 17,000-acre Muckross estate in Co. Kerry, adjoining the lakes of Killarney, which he bought for £60,000 to prevent the land being exploited by a commercial syndicate, thus enabling it to continue as an important tourist attraction.“

Another brother, Benjamin Lee (1842-1900) who went by his middle name Lee, married Henrietta Eliza St. Lawrence of Howth Castle. It was their son who became the 3rd Baronet of Ashford Castle.

Edward Cecil Guinness, the Dictionary of Biography tells us, was: “Socially innovative, with a concern for the welfare of employees, from as early as 1870 he had established a free dispensary for his workforce and made provisions for pension and other allowances – acts of social reform that were remarkable for the time. To mark his retirement in 1890 he placed in trust £250,000 to be expended in the erection of working-class housing in London and Dublin.“

Before the Iveagh Market was built in 1906, hundreds of traders sold their goods outdoors, especially around St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and the area was a maze of poor and dirty streets and alleys with homes, as the city council said, “unfit for human habitation.” Children were sent out by their parents to work selling goods in the streets, and women tried to make money as dealers selling fish, flowers, old clothes and fruit.

Edward Cecil Guinness cleared the markets in the area to build a park and housing for the labouring poor – you can see the beautiful Victorian style brick buildings still run by the “Iveagh Trust” around St. Patrick’s Cathedral. He donated what in today’s money would be almost 20 million euro for the new housing. As the traders had long established market rights, he built a new market building, moving trading indoors, in the tradition of Victorian covered markets.

Edward’s main residence at the time he purchased Farmleigh was 80 St. Stephen’s Green, now Iveagh House, the headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs. He viewed Farmleigh as ‘a rustic retreat’.

Let’s take a quick diversion to Iveagh House (80 and 81 St. Stephen’s Green), which I was lucky enough to visit during Open House Dublin in 2014. 80 St. Stephen’s Green was built for Bishop Robert Clayton (1695-1758), Bishop of Cork and Ross, by Richard Castle in 1736. After both number 80 and 81 were bought by Benjamin Guinness in 1862, he acted as his own architect and produced the current house, combining the two houses. [see Archiseek] In 1866 a Portland stone facade by James Franklin Fuller was added.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography entry by C. J. Woods tells us that Archbishop Robert Clayton was born in England to John Clayton (1657–1725) and his wife, Eleanor (née Atherton). John Clayton moved to Ireland as prebendary of St Michan’s, Dublin (1698–1725), and was later dean of Kildare (1708–25). On his father’s death Robert inherited his estate and so could afford to resign his fellowship and marry, which he did on the same day (17 June 1728), marrying Catherine Donnellan (1703?–1766), a daughter of Nehemiah Donnellan, chief baron of the Irish exchequer. Robert inherited estates in England, and had a fine house built on the south side of St Stephen’s Green, designed in Italian style by Richard Castle in the mid 1730s. He also acquired a country house in Co. Kildare, St Wolstan’s near Celbridge (1752), and spent freely. He and his wife had no children.

The Archiseek website tells us about Iveagh House:

“The Dublin Builder, February 1 1866: ‘In this number we give a sketch of the town mansion of Mr. Benjamin Lee Guinness, M.P, now in course of erection in Stephen’s Green, South, the grounds of which run down to those of the Winter Garden. As an illustration so very quiet and unpretending a front is less remarkable as a work of architectural importance than from the interest which the name of that well-known and respected owner gives it, and from whose own designs it is said to have been built. The interior of the mansion promises to be of a very important and costly character, and to this we hope to have the pleasure of returning on a future occasion when it is more fully advanced. The works, we believe, have been carried out by the Messrs. Murphy of St. Patrick’s Cathedral notoriety, under Mr. Guinness’s own immediate directions, without the intervention of any professional architect.’ “

The Farmleigh website tells us of the Guinness family’s source of wealth: “In 1886 Edward Cecil Guinness floated the brewery on the Stock Exchange increasing his wealth and social standing and this reflected in an extensive rebuild of Farmleigh. Despite this work, Edward and his wife Adelaide spent relatively little time there. Their primary residence was in London, but when in Dublin, they stayed mostly at 80 St. Stephen’s Green. The family only stayed in Farmleigh for short periods of a couple of weeks, mainly in the spring and summer months.“

80/81 St. Stephen’s Green was donated to the Irish government by Benjamin Guinness’s grandson Rupert, the 2nd Earl of Iveagh, in 1939 and was renamed Iveagh House.

One enters Iveagh House through a large nineteenth century entrance hall with two screens of Ionic columns, which incorporates the front parlour of the Clayton house. The hall is adorned with sculptures bought by the Guinnesses at the Dublin Exhibition of 1865. Through a door at the west end is a Victorian domed vestibule and beyond it a service stair. East of the hall is an Inner Hall that was the entrance hall of Bishop Clayton’s house. This has niches flanking the chimney breast, fielded panelling and a modillion cornice.

The two stair compartments of the eighteenth century house on St. Stephen’s Green were combined to create the space for the grand imperial staircase inserted by James Franklin Fuller in 1881.

The drawing room’s ceiling is modelled on the Provost of Trinity House dining room ceiling. There is also a room downstairs in Iveagh House with a room which was added in 1866 with Georgian Revival ornament derived from the Provost’s House.

The Music Room at the head of the stairs has a Rococo-cum Neoclassical ceiling of the late 1760s.

Christine Casey describes the ballroom of Iveagh House, which was designed, as was that in Farmleigh, by William Young. Casey writes in her Buildings of Ireland: Dublin book (p. 498): “This is an impressive if vulgar room. Tripartite, with a big shallow central dome and lower vaulted end bays with canted bay windows overlooking the garden. Elaborate, almost Mannerist stucco decoration by D’Arcy’s of Dublin.”

The ballroom, our guide to Iveagh House told us, was created to host a Royal visit. The room was built specially to have room for the guests, for £30,000.

Now that we have placed Edward Cecil Guinness in the context of the house he lived in at the time of purchasing Farmleigh, let’s return to Farmleigh.

Casey writes that inside Farmleigh, two ranges of rooms open off an east-west spinal corridor, with a “showy” central entrance hall opening through a columnar screen to a large top-lip double-height stair hall.

The immediate front hallway is also toplit by roundels set in the ceiling of the hallway/porte cochere. The porte cochere is upheld by Portland stone pilasters and there is a screen of six columns of Connemara marble on pedestals with Ionic capitals on pedestals. The columns support the coffered ceiling of the Entrance Hall.

The chimneypiece is of carved and inlaid marble, and the website tells us it is probably a nineteenth-century copy of an original, though the plaque may date from the eighteenth century.

The doors leading off the hall have carved mouldings and pediments, and the doors are of veneered mahogany on the hall side and of oak on the other.

The website continues: “The classical motif continues at the Staircase to the rear of the hall. Corinthian pilasters rise from first-floor level to a strongly projecting cornice. San Domingo mahogany is used for the Staircase on which the wrought iron balusters were made to correspond exactly with those on the staircase of Iveagh House, formerly the Earls of Iveaghs’ city mansion.“

The stairwell is toplit also.

After Edward Cecil’s death in 1927 his eldest son Rupert became the second Earl of Iveagh and inherited Farmleigh and 80 St Stephen’s Green. He was a British MP for Southend at the time, and ceased to be an MP when he succeeded to his father’s earldom. His wife Gwendolen the Countess of Iveagh won the Southend by-election in November 1927 to replace her husband as MP. She served until her retirement in 1935.

He presented the house on St. Stephen’s Green to the Irish State in 1939.

The website tells us about the family in Farmleigh: “Rupert gave Farmleigh to his grandson and heir, Benjamin (Rupert’s eldest son and Benjamin’s father, Arthur, was killed in WWII). Farmleigh became a family home for Benjamin (3rd Earl of Iveagh) and Miranda Guinness, and their children. Benjamin became a keen bibliophile and collector of rare books, parliamentary and early bindings, as well as first editions of the modern poets and playwrights. The library in Farmleigh in now dedicated to Benjamin Iveagh and his wonderful collection of books.

“Benjamin died in 1993 in London and in 1999, his son Arthur Guinness (4th Earl of Iveagh), sold Farmleigh to the Irish State.” [2]

The website continues:

“The door to the left of the hall leads to the Dining Room, which is lined with boiseries in the style of Louis XV. There is some spectacular woodcarving in this room, of particular note is the chimney piece, supported by a pair of female herms, with a clock at its centre surmounted by a grotesque face. Bronze figures of Bacchantes are placed in the shell-topped niches on either side of the fireplace, while beneath them are late Victorian oak buffets. The London firm of Charles Mellier & Co., supplied the interior here (apart from the ceiling which was designed by the architect J.F. Fuller).”

The Dining Room panelling was designed by decorators Charles Mellier & Co to incorporate four late seventeenth century Italian tapestries which once belonged to Queen Maria Christina of Spain. Three of the embroidered panels have been identified as the planetary gods, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn. These panels are likely to be part of a larger set of seven panels relating to the Roman deities. One such panel, apparently from the same set and depicting Mercury, is in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. The fourth panel above the fireplace is thought to depict a personification of Africa and to be part of a further set, depicting the continents.

Beyond the dining room is Guinness’s Study, a wainscoted room with a sky painted ceiling. A concealed door next to the window at the southwest corner led to a basement stronghold, a secret chamber for Guinness to escape in case of attack.

The website tells us:

“The main entrance to Farmleigh was originally on the north side of the house (in part of what is now the Library) and this was probably a reception room where guests either dined or withdrew after dinner. By 1873, when Edward Cecil Guinness bought the house, the entrance had been changed to the south of the building and this room was the entrance hall. It subsequently became a boudoir and reverted in later years with the Guinness family to a reception room while keeping its appellation as ‘boudoir’. (Generally the boudoir was a ‘private’ room for the lady of the house, decorated in a light and elegant style. Her ‘public’ room was the drawing room, just as the gentleman’s study was his ‘private’ room and the library his ‘public’ room.).

“The Boudoir is oval in shape with two niches, one each side of the door into the Corridor. The niche to the right of the door as one enters contained a jib door into the Oak Room but the space between the rooms now holds a safe accessed from the Oak Room.“

Christine Casey describes the Oak Room in her Buildings of Ireland: Dublin (p. 298). She writes: “On the right of the hall is the studiolo-like Oak Room, which has a coffered oak ceiling and tall panelling with pilasters, scalloped tympana and grotesque terms. …Beefier and more textured than most of the carving at Farmleigh. It has been suggested that Fuller used salvaged panelling, although the regularity of execution seems at odds with the seventeenth century style.”

The website describes the Boudoir: “The ceiling plasterwork dates from about 1790 and is in the Adam style, with husk chains and classical motifs in medallions surrounding the central decoration of a fan-like or bat’s-wing motif, which is itself echoed in the heads of the niches. The unusual medallion motifs here are similar to those in a ceiling in 35 North Great George’s Street, Dublin which has been attributed to Francis Ryan or Michael Stapleton and dated to 1783. It is in particularly fine condition and clearly articulated without excessive applications of paint.

“During the OPW restoration work, it was possible to examine the original decorations and colour scheme of the Georgian house here because the ceiling heights had been changed in the Guinness alterations. Particular attention has been paid in the selection of fabrics for this room to reflect its character.

“An item of particular interest is the pair of engraved brass lock-plates on the door into the corridor which are similar to some in Iveagh House where they are original to that 1736 house! They are the only examples of these at Farmleigh and it is presumed that they got here through Fuller who also worked at Iveagh House.“

One of the former drawing rooms is now called the “Nobel Room” and honours the memory of Ireland’s four Nobel Laureates for literature: George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. It interconnects with the “Blue Drawing Room.” These rooms were significantly re-modelled by Fuller in the 1880s, and again in the 1890s by William Young. The saucer-domed ceiling in the Nobel Room is in the style of the 1820s and its plasterwork of vine-leaves, grapes and vases filled with fruit and flowers indicates that it may have been a dining room. A clever touch is the window over the fireplace, an unusual feature. Christine Casey writes: “Taking a leaf from Charles Barry’s book, Fuller went to pains to move the fireplace to the centre of the rear wall to create an arresting overmantel window.”

The Blue Room is an ante room to the Ballroom. The ceiling was copied from that in the Oval Room, though it is not at all as finely executed as the original. The three arched doorways in these rooms were created out of windows in the old house when Young added the Ballroom in 1896.

The suite for state guests, which is not included in the house tour, is inspired by designs of Irish modernist Eileen Gray (you can see examples of her work in the Museum at Collins Barracks in Dublin).

The house also contains the Benjamin Iveagh Library, donated by the Guinness family to Dublin’s Marsh’s Library and on permanent display in Farmleigh. The Library, which is panelled in Austrian Oak with exquisitely rendered carvings in the neo – Jacobean style, was part of the renovation undertaken by Edward Cecil in the 1880s. Scholars can access material from the collection by arrangement. The Benjamin Iveagh Library is open for use by suitably qualified scholars, third-level students, and independent researchers. A full electronic catalogue of the collection may be viewed online via Marsh’s Library.

Applications to carry out research in the Benjamin Iveagh Library may be made to the Keeper of Marsh’s Library.

Email: reading.room@marshlibrary.ie

The librarian Nuala Canny writes:

“While the printed works which include many rare imprints and early periodicals represent the majority of the holdings, there is some exceptional manuscript material, including a copy of the Topography of Ireland by Gerald of Wales c.1280, and the trilingual language primer used by Queen Elizabeth I c. 1564 to learn Irish, together with letters from Sean O’Casey, W.B. Yeats, Lennox Robinson, Daniel O’Connell and Roger Casement.

“The items that adorn these shelves represent important moments in the areas of Irish Politics, Literature, and Science: we have a triumphant letter from Daniel O’Connell to his wife in 1829 telling her of the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which led to Catholic Emancipation, a first edition of James Joyce’s seminal work Ulysses published in 1922 and the first appearance in print in 1662 of Boyle’s Law.”

The Ballroom with adjoining conservatory is the piéce de resistance of the house. The ballroom was designed by William Young in 1892. It is a large rectangular room with bows in the centre of the north, east and south walls. Casey writes that “it is a much more reticent affair than the showy marble ballroom that Young designed the Guinness townhouse at St. Stephen’s Green [as pictured above].”

The website tells us:

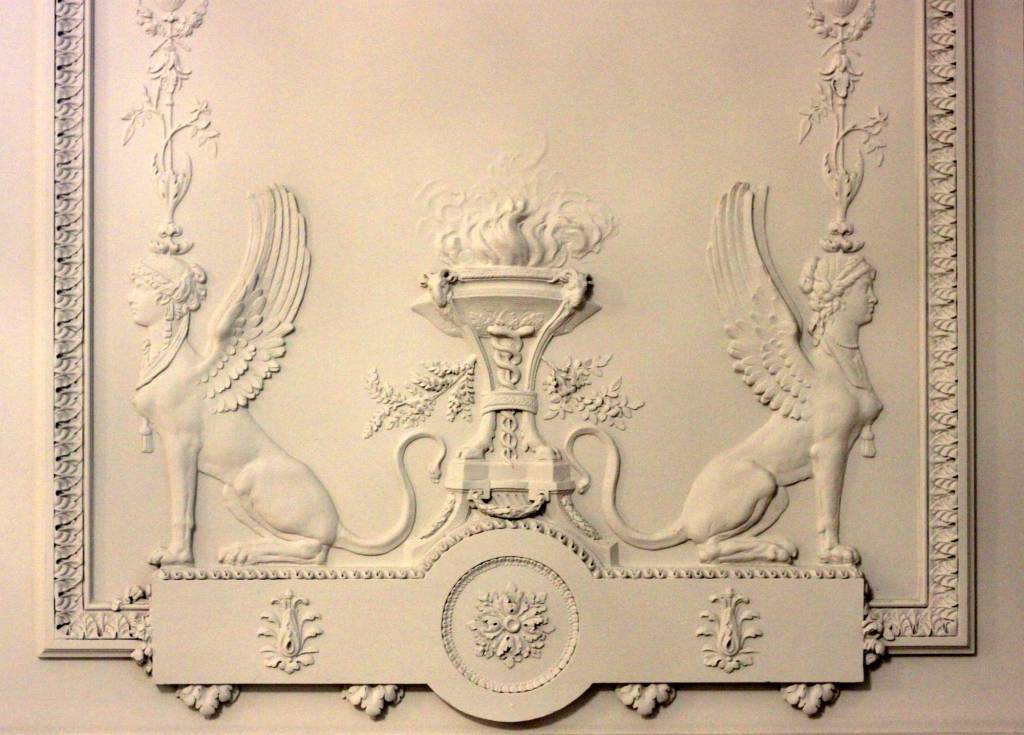

“The Guinness’ guests could not fail to be impressed with the superb decoration in the style of Louis XVI with swags, wreaths, musical trophies, urns, sphinxes, and Corinthian pilasters. The rich decoration is executed in plaster that is applied to wood panelling, and the whole room, including the ceiling, is painted off-white to resemble plaster. The chimney piece is also made of wood and this, together with the overmantel, the ceiling, and the elegant portieres, were all part of an integrated scheme designed by Young. The Edinburgh-based interior design company Morrisons probably supplied the portieres as they had done so for the Young-designed ballroom at Iveagh House.“

The plaster decoration is also by Mellier.

“Hanging from the centre of the ceiling is a magnificent late nineteenth-century cut-glass and gilt metal chandelier complete with coronet. Purchased specifically for the Ballroom, it is on loan from the Guinness family. There is a story that the oak floor was made from disused barrels at the brewery but that has never been confirmed!“

The Conservatory: “Erected in 1901-2, it was supplied by Mackenzie and Moncur of Edinburgh, on the recommendation of Young. Exotic plants and flowers were grown here, and have been re-introduced by the Office of Public Works. Hot water pipes that ran around the perimeter were covered up by cast iron grilles, which have been restored. The marble floor, which is original, is tiled in the traditional eighteenth-century pattern of carreaux octagons.

“This room posed one of the most difficult conservation problems for the OPW at Farmleigh, as it was in a dangerous condition when the State took over the house. It was completely re-glazed and new structural supports for high-level metal work were introduced. As a result the character of the Conservatory has been retained and its life span increased for at least another 100 years.“

A room we don’t see on the tour is discussed on the blog on the Farmleigh website: the Billiard Room:

“Located at mezzanine level between the ground and first floors, typical of nineteenth century billiard rooms to keep offending cigar odours away from the rest of the house and male visitors appropriately distanced from visiting ladies, it is very much a masculine enclave. Beneath a top-lit roof – reconstructed and reglazed with ultraviolet screens by the OPW – the plaster cornice, deep ceiling cove and decorative ribs are painted in imitation of timber. The oak chimneypiece with Corinthian columns and carved frieze to the south of the room is dark in colour, lending to the heaviness about the overall decor when combined with the distinctive red cotton wall fabric which is printed with an arabesque motif.“

The grounds contain a clock tower, a large classical fountain in the Pleasure Grounds, an ornamental dairy, garden temple and four acre walled garden and sunken garden. The outbuildings have been adapted to house an art gallery and a theatre and a courtyard for additional state accommodation. The Boathouse now houses a cafe overlooking the lake.

“Sunken gardens in various formal styles were popular in the early twentieth century… This one is in the Dutch of Early English style and was created some time after 1907, probably by Edward Cecil Guinness. The design has some similarities with the sunken pond garden at Hampton Court, which dates from the original Early English period, and may relate to his connections with the British Royal family.

“An ornamental gate leads into the rectangular garden, which was designed with three descending brick terraces leading to an oval pool in the centre, with a marble fountain of carved putti figures. The fountain has been restored under the direction of OPW and the Carrara marble exposed. Fine topiary peacocks and spirals surround this fountain on two levels. A brick wall enclosing the garden is paralleled by a high yew hedge, which leads the eye to the two conifers framing the view to the small apple orchard beyond.” [3]

“The Walled Garden covers about four acres and is sloped ideally towards the south. A fine pair of highly decorative wrought iron gates lead into a diagonal walk with double herbaceous borders backed by high yew hedges. South of the main crosswalk is a small orchard and potager, while north of it there is a small rose and lavender garden. The Walled Garden dates from the early nineteenth century, when Charles Trench owned Farmleigh; it is shown on the 1837 Ordnance Survey map as having a diagonal layout with seven squares and glasshouse. Later that century it had an extensive range of glasshouses on the south wall for many plants grown in typical Victorian fashion to support large-scale bedding schemes as well as producing exotic fruit and flowers and foliage, particularly orchids and ferns, for year round display in the house.

“Among the additions made by Edward Cecil Guinness were the small Victorian fernery under glass and grotto nearby with two old ogee windows from St Patrick’s Cathedral in the end wall of the garden. He also erected a number of glasshouses, including a fine three quarter span cast-iron vinery behind the high yew hedge, the potting shed, and the gardener’s house and pump house which were built in the Arts and Crafts style. His daughter in-law, Gwendolen, Lady Iveagh, subsequently created a compartmentalised layout, which was fashionable in the early twentieth century along with renewed interest in old style garden plants and herbaceous borders. A new traditional path led from the wrought iron gateway connecting the Walled Garden to the broad walk at the back of the house. This new axis of the garden was reinforced by tall yew hedges backing the long double herbaceous borders which she also planted.

“A stone temple was created as a focal point of the garden by Benjamin and Miranda Guinness in 1971: it has six antique columns of Portland with a copper roof and ornamental weather vane. The main cross path either side of the temple has metal structures designed by Lanning Roper for climbing roses and wisteria similar to those in the famous Bagatelle Garden in Paris. A paved rose garden was laid out to the north east of the temple backed by a yew hedge and looking across a lawn to the small orchard and potage. Lanning Roper suggested planting a quince, a mulberry, a catalpa, and a magnolia, to complete what he described as a Carolingian Quartet on this lawn. Lady Iveagh subsequently planted the double herbaceous borders, which include yuccas, phormiums, paeonies, astilbe and euphorbias.” [4]

[1] See also https://farmleigh.ie/

[2] https://farmleigh.ie/the-guinness-family/