Emo Court, County Laois:

General enquiries: 057 862 6573, emocourt@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/:

“Emo Court is a quintessential neo-classical mansion, set in the midst of the ancient Slieve Bloom Mountains. The famous architect James Gandon, fresh from his work on the Custom House and the Four Courts in Dublin, set to work on Emo Court in 1790. However, the building that stands now was not completed until some 70 years later [with work by Lewis Vulliamy, a fashionable London architect, who had worked on the Dorchester Hotel in London and Arthur & John Williamson, from Dublin, and later, William Caldbeck].

“The estate was home to the earls of Portarlington until the War of Independence forced them to abandon Ireland for good. The Jesuits moved in some years later [1920] and, as the Novitiate of the Irish Province, the mansion played host to some 500 of the order’s trainees.

“Major Cholmeley-Harrison took over Emo Court in the 1960s and fully restored it [to designs by Sir Albert Richardson]. He opened the beautiful gardens and parkland to the public before finally presenting the entire estate to the people of Ireland in 1994.

“You can now enjoy a tour of the house before relaxing in its charming tearoom. The gardens are a model of neo-classical landscape design, with formal lawns, a lake and woodland walks just waiting to be explored.” [2]

We visited Emo during Heritage Week 2024 as some rooms were open to the public – finally! Despite the episode on television several years ago of “Great Irish Interiors” where the house was prepared to be open to the public, it is still not open to the public. And it is still not. Just a few rooms were open for Heritage Week. Major Cholmeley-Harrison will be tearing his hair out, if he has any left, in his grave – imagine giving the house to the state, and the state accepts it and then closes it for thirty years!

It was so exciting to go inside. My great uncle Father Tony Baggot was a novitiate there when the Jesuits owned the property.

Unfortunately I was not allowed to take photographs. I was not impressed by the reason given: it’s not finished yet. For goodness sake, who do the OPW think owns the house? We do! Apparently they had left it arranged as when owned Major Cholmeley-Harrison, opened it for a short while, and now they are removing traces of him from several areas. Poor Mr. Cholmeley-Harrison.

Mark Bence-Jones tells us that the 1st Earl of Portarlington was interested in architecture and was instrumental in bringing James Gandon to Ireland, in order to build the new Custom House. The name Emo is an Italianised version of the original Irish name of the estate, Imoe. [3]

The Emo Court website tells us of the history:

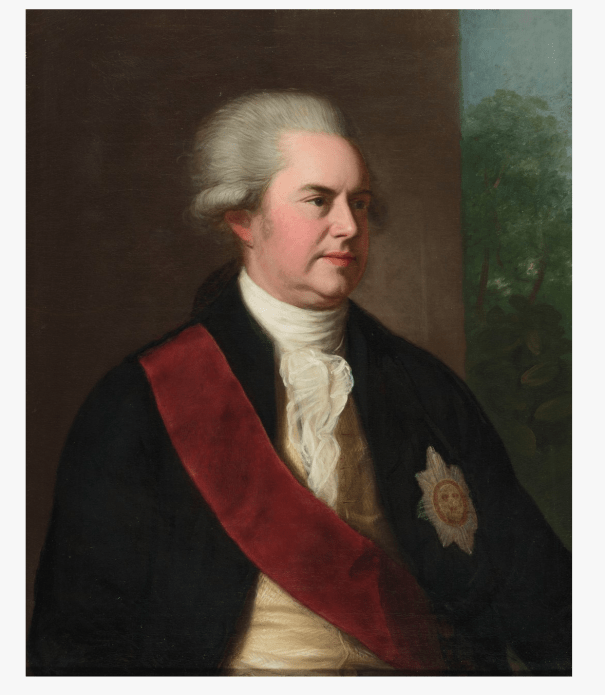

“John Dawson, 1st Earl of Portarlington [1744-1798] commissioned the building of Emo Court in 1790 although the house was not finally completed until 1870, eighty years later. Emo Court is one of only a few private country houses designed by the architect James Gandon. Others were Abbeyville, north Co. Dublin for Sir James Beresford [or is it John Beresford (1738-1805)? later famous for being the home of politician Charles Haughey] and Sandymount Park, Dublin for William Ashford. In addition, Gandon built himself a house at Canonbrook, Lucan, Co. Dublin.” [4]

Many of Gandon’s original drawings, plus those of his successors, are in the Irish Architectural Archive, 45 Merrion Square, Dublin. [5] The Emo Court website continues:

“James Gandon was born in London of Huguenot descent. He studied classics, mathematics and drawing, attending evening classes at Shipley’s Academy in London. At the age of fifteen, James was apprenticed to the architect Sir William Chambers and about eight years later, set up in business on his own. His first connection with Ireland was in 1769 when he won the second prize of £60 in a competition to design the Royal Exchange in Dublin, now the City Hall. He was invited to build in St Petersburg, Russia, by Princess Dashkov, and offered an official post with military rank. However, he chose instead to accept an offer from Sir John Beresford and John Dawson, Lord Carlow, later 1st Earl of Portarlington, to come to Dublin to build a new Custom House. This was begun in 1781. The following year, Gandon was commissioned to make extensions to the Parliament House, originally designed by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce. Here he added a Corinthian portico as entrance to the Lords’ Chamber. After the Act of Union in 1801, the building became the Bank of Ireland. In 1785, Gandon was commissioned to design the new Four Courts. The third of his great Dublin buildings was the King’s Inns, begun in 1795. His few private houses were designed for patrons and friends.” [see 4]

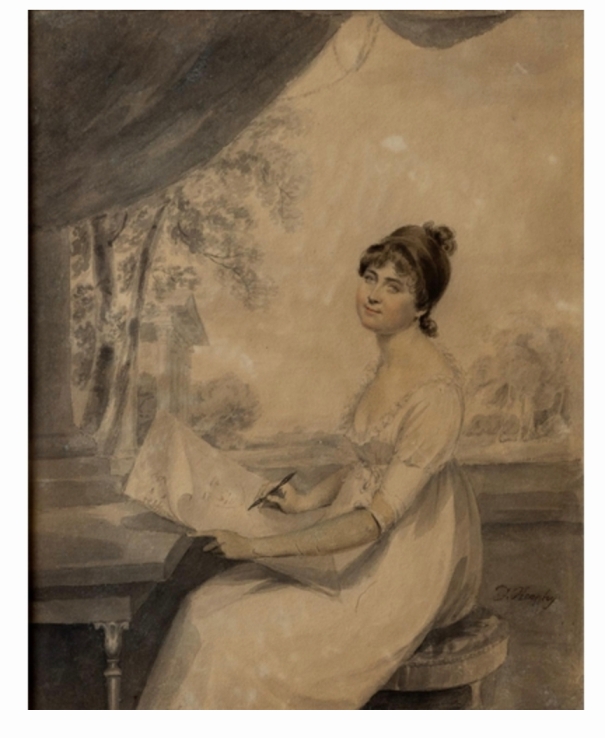

The website continues: “In the early 18th century, Ephraim Dawson [1683-1746], a wealthy banker, after whom Dawson Street in Dublin is named, purchased the land of the Emo Estate and other estates in the Queen’s County (Co. Laois). He married Anne Preston, heiress to the Emo Park Estate and fixed his residence in a house known as Dawson Court, which was in close proximity to the present Emo Court. His grandson, John Dawson, was created 1st Earl of Portarlington in 1785. Three years later, he married Lady Caroline Stuart, daughter of the [3rd] Earl of Bute, who was later Prime Minister of England. John Dawson commissioned Gandon to design Emo Court in 1790.“

Stephen’s ancestor Earl George Macartney married another daughter of the 3rd Earl of Bute! Their mother was the wonderful Lady Mary Wortley-Montague whose husband was a diplomat and she wrote memoires of their travels. She even visited a harem.

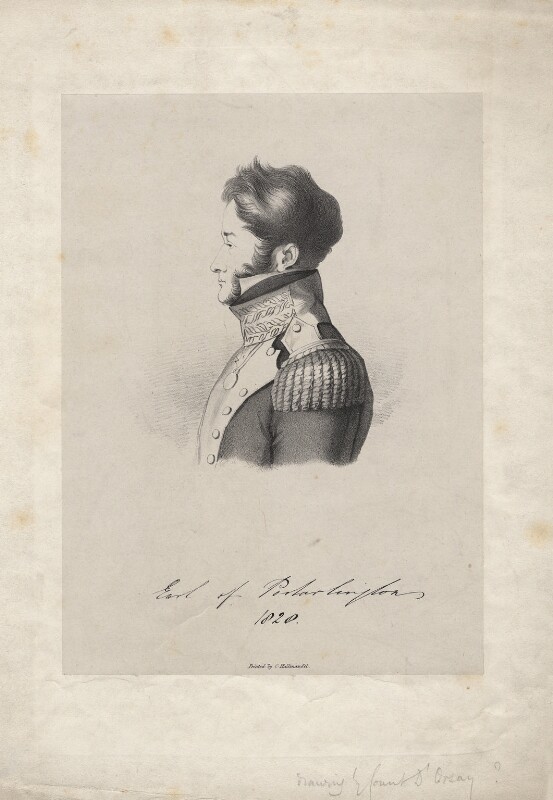

“After Gandon died in 1823, to be buried in Drumcondra churchyard, the 2nd Earl of Portarlington, also John Dawson, engaged Lewis Vulliamy, a fashionable London architect, who had worked on the Dorchester Hotel in London and A. & J. Williamson, Dublin architects, to finish the house. In the period, 1824-36, the dining room and garden front portico with giant Ionic columns were built, but on the death of the 2nd Earl in 1845, the house still remained unfinished. It was not until 1860 that the 3rd Earl, Henry Ruben John Dawson [or Dawson-Damer, the son of the 2nd Earl’s brother Henry Dawson-Damer, who had the name Damer added to his name after the family of his grandmother, Mary Damer, who married William Henry Dawson, 1st Viscount Carlow] commissioned William Caldbeck, a Dublin architect, and Thomas Connolly, his contractor, to finish the double height rotunda, drawing room and library.” [see 4] Caldbeck also added a detached bachelor wing, joined to the main block by a curving corridor.

Although it was not built during Gandon’s time, most of the house is as it was designed by Gandon, wiht some additions or changes. Mark Bence-Jones describes the house:

“Of two storeys over a basement, the sides of the house being surmounted by attics so as to form end towers or pavilions on each of the two principal fronts. The entrance front has seven bay centre with a giant pedimented Ionic portico; the end pavilions being of a single storey, with a pedimented window in an arched recess, behind a blind attic with a panel containing a Coade stone relief of putti; on one side representing the Arts, on the other, a pastoral scene. The roof parapet in the centre, on either side of the portico, is balustraded. The side elevation, which is of three storeys including the attic, is of one bay on either side of a curved central bow.” [see 3]

Bence-Jones continues: “The house was not completed when the 1st Earl died on campaign during 1798 rebellion; 2nd Earl, who was very short of money, did not do any more to it until 1834-36, when he employed the fashionable English architect, Lewis Vulliamy; who completed the garden front, giving it its portico of four giant Ionic columns with a straight balustraded entablature, and also worked on the interior, being assisted by Dublin architects named Williamson. It was not until ca 1860, in the time of 3rd Earl – after the house had come near to being sold up by the Encumbered Estates Court – that the great rotunda, its copper dome rising from behind the garden front portico and also prominent on the entrance front, was completed; the architect this time being William Caldbeck, of Dublin, who completed the other unfinished parts of the house and added a detached bachelor wing, joined to the main block by a curving corridor.” [see 3]

The website continues: “Emo court remained the seat of the Earls of Portarlington until 1920, when the house and its vast demesne of over 4500 ha, (11,150 acres), was sold to the Irish Land Commission. After the Phoenix Park in Dublin, Emo Court was the largest enclosed estate in Ireland. The house remained empty until 1930 when 150 ha., including the garden, pleasure grounds, woodland and lake were sold to the Society of Jesus for a novitiate. The Jesuits made several structural changes to the building to suit their purposes, including the conversion of the rotunda and library as a chapel. The distinguished Jesuit photographer, Fr Frank Browne lived at Emo Court from 1930-57. [7] A notable novitiate was the Irish author, Benedict Kiely.

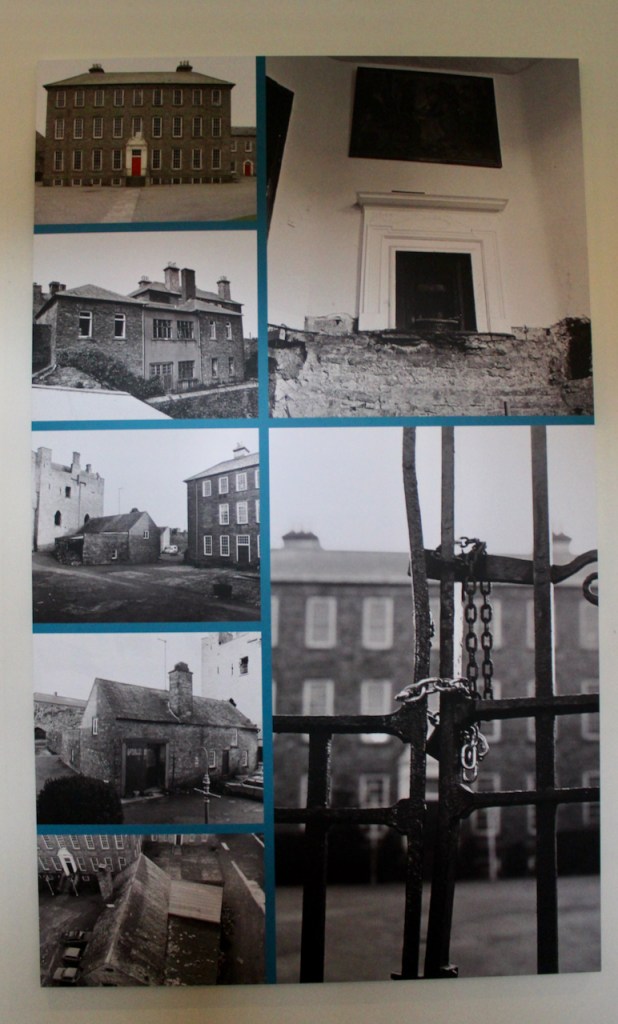

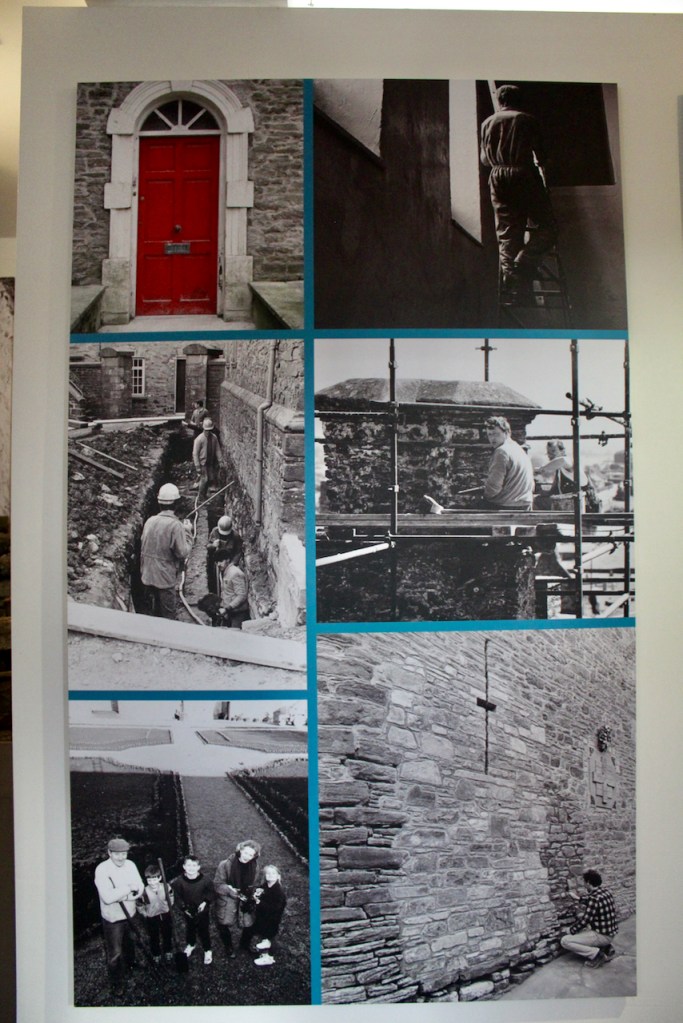

“The Jesuits remained at Emo until 1969 and the property was eventually sold to Major Cholmeley Dering Cholmeley-Harrison. He embarked upon a long and enlightened restoration, commissioning the London architectural firm of Sir Albert Richardson & Partners to effect the restoration.

“In 1994, President Mary Robinson officially received Emo Court & Parklands from Major Cholmeley-Harrison on behalf of the Nation.” [see 4]

Unfortunately Emo Park house has been closed to the public for renovation for several years, and was closed on the day we visited in July 2021. I am looking forward to seeing the interior, which from photographs and descriptions I have seen, look spectacular. From the outside we gain little appreciation of the splendid copper dome.

In the meantime, you can read more about Emo and see photographs of its interiors on the wonderful blog of the Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne. [8]

There are beautiful grounds to explore, however, on a day out at Emo, including picturesquely placed sculptures, an arboretum, lake, and walled garden. Here is a link to a beautiful short film by poet Pat Boran, about the statues at Emo Park, County Laois. https://bit.ly/35uXPO1

[1] p. 336. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[2] https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/

[3] p. 119. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://emocourt.ie/history/

For information on Gandon’s house in Lucan, see https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/11201034/canonbrook-house-lucan-newlands-road-lucan-and-pettycanon-lucan-dublin

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2019/02/27/emo-court/

[6] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/media/81101

[7] http://www.fatherbrowne.com

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/14/of-changes-in-taste/

and https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/02/01/seen-in-the-round/

For photographs of the stuccowork, see https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/21/forgotten-virtuosi/