See the website for opening times. It is also available for hire, and we attended a party there in 2015!

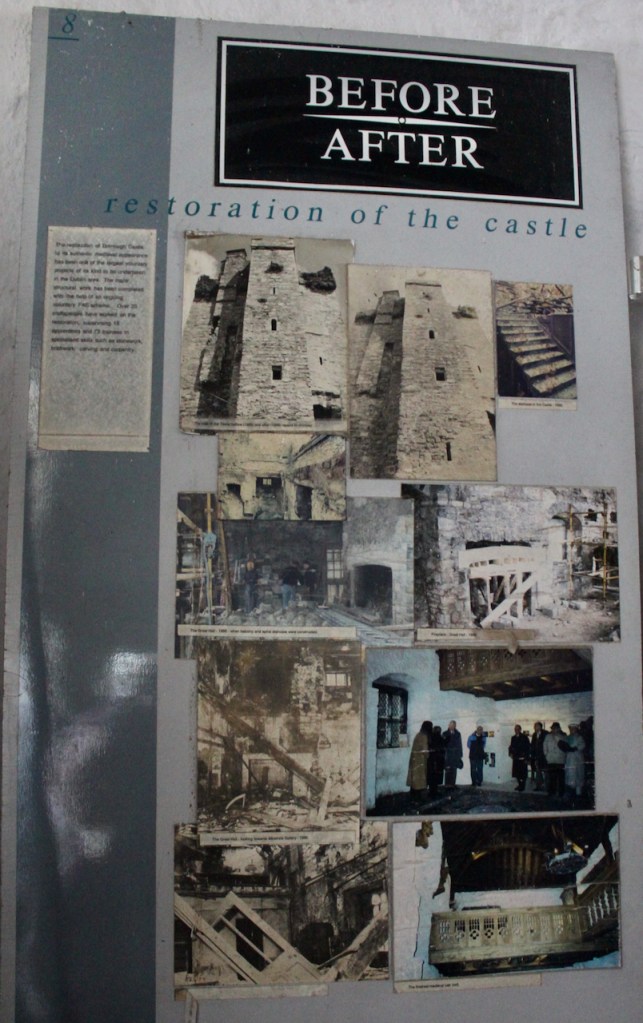

We visited again in 2023, with a tour given by Peter Pearson for the Irish Georgian Society. Peter Pearson was instrumental in saving the Castle from destruction. In 1985 he “swung across the moat on a rope” to see the state of the building, which had been unoccupied since the 1960. Many individuals and organisations were involved in the early stages of restoration, including An Taisce, FAS, CYTP, and the Drimnagh and Crumlin community. Over 23 craftspeople worked on the restoration, supervising 15 apprentices, and 73 trainees in specialised skills such as stonework, brickwork, carving and carpentry.

The website tells us: “Nestled in the heart of South Dublin, Drimnagh Castle stands as a meticulously restored Norman Castle, boasting the distinction of being the sole remaining moated castle in Ireland. Once the esteemed seat of the de Bernival family, who were granted lands in Drimnagh and Terenure by King John in 1215, the castle now serves primarily as a cherished heritage site.” King John granted the land to Hugh alias Ulfran de Barneville.

“Guided tours offer visitors the opportunity to explore the castle and its enchanting gardens. Moreover, the castle is available for hire, making it an ideal venue for presentations, School projects, product launches, photo shoots and even as a captivating film location!“

The website describes the Castle: “Its rectangular shape enclosing the castle, its gardens and courtyard, created a safe haven for people and animals in times of war and disturbance. The moat is fed by a small stream, called the Bluebell. The present bridge, by which you enter the castle, was erected in 1780 and replaced a drawbridge structure.“

I took notes the day Peter Pearson gave the tour but I don’t have them to hand so will have to add more information to this entry later!

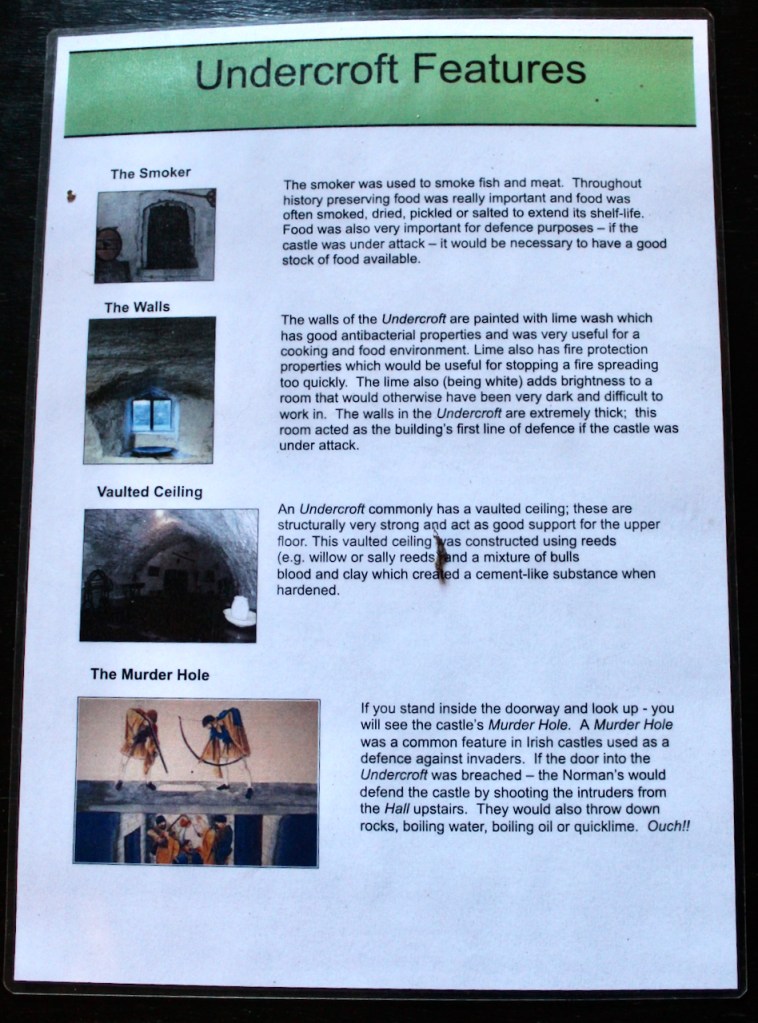

The website continues: “Above the entrance of the tower, as the visitor comes through the large gateway is a ‘murder hole’. Rocks, stones, boiling water or limestone were poured down upon the head of any enemy attempting to break in. The main castle to the right of the tower was built in the 15th century, and the tower was built in the late 16th. The porch and stairways were built in the 19th century and the other buildings are 20th century.“

The walls of the castle are built of local grey limestone known as calp and the stone was probably drawn from one of the many nearby quarries. The walls are about 3-4 feet thick.

The website tells us “The tower was built in the late 16th or early 17th century. The tower is approximately 57 feet high and commands a great view of the surrounding countryside. Most of the castles at Ballymount, Terenure and Rathfarnham could have been seen from the top of the battlements.“

The website tells us: “In 1215 the lands of Drymenagh and Tyrenure were granted to a Norman knight, Hugo de Bernivale, who arrived with Strongbow. These lands were given to him in return for his family’s help in the Crusades and the invasion of Ireland. De Bernivale selected a site beside the “Crooked Glen” , the original Cruimghlinn, that gives its name to the townland of Crumlin, and there he built his castle. This “Crooked Glen” is better known today as Landsdowne Valley, through which the river Camac makes its way to the sea. The lands around Drimnagh at this time were rising and falling hills and vast forests stretching to the Dublin mountains. All through the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries the area around the castle was sparsely populated and a document shows that only around 11 people lived in the area during the 18th century.“

In The Landed Gentry and Aristocracy Meath, volume 1, by Art Kavanagh, published in 2005 by Irish Family Names, Dublin 4, he tells us that as a result of the foray into Ireland by the Bernevals in 1215 with Prince John, they were granted lands in Dublin in the Drimnagh, Kimmage, Ballyfermot and Terenure areas, where they settled until Cromwellian times.

The website tells of: The early years of the Barnewalls at Drimnagh Castle

“The Barnewall’s (anglicised from De Berneval) were not just owners of land in Drimnagh, but owned land and fortified castles all over Ireland, such as Crickstown and Trimblestown. They were involved in many events in Irish history and held positions in Irish Parliament and in military campaigns against the Irish. The Barnewall family crest has powerful warrior symbols and a Latin inscription, “I would rather die than dishonour my name”. You can see a reproduction of this crest over the fireplace in the Great Hall in the now restored castle.”

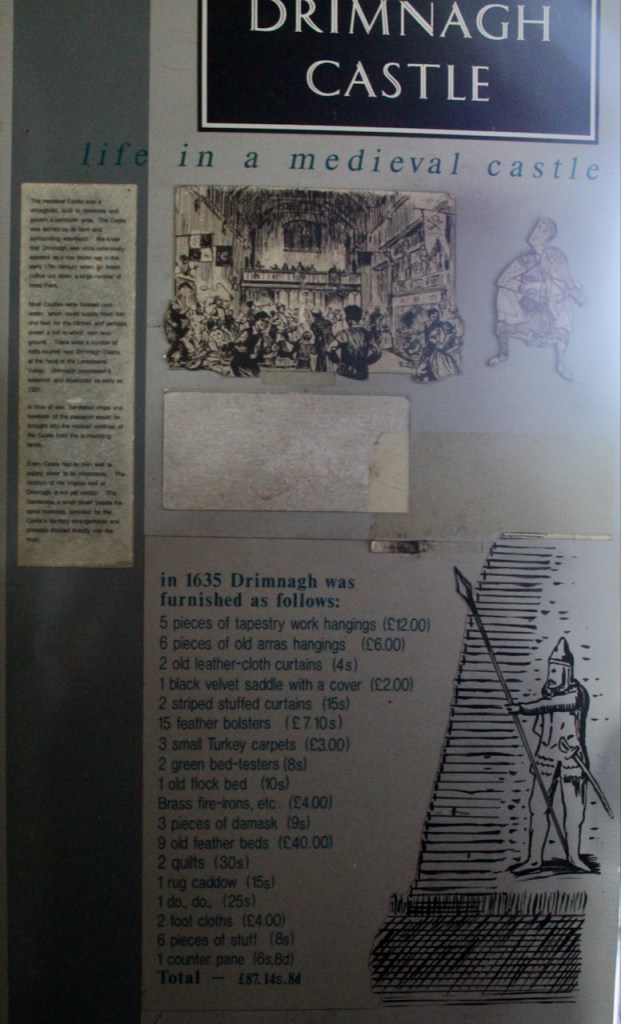

An information board in the castle tells us that in 1435 Luke Barnewall became trustee of the lands in Drimnagh Castle, including three houses, two mills and a dovecote.

An information board in the castle tells us that a medieval castle was a stronghold built to dominate and govern an area. The castle was served by its farm and surrounding woodland. Drimnagh was once extensively wooded. There were also mills located near Drimnagh Castle, as early as 1331.

The website tells us that: “[The Drimnagh Barnewall line] terminated in an heiress, Elizabeth, daughter of Marcus Barneval of Drumenagh, who married James Barnewall of Bremore, and sold the property, 1st February 1607, to Sir Adam Loftus, Kt. of Rathfarnham.“

This must be Adam Loftus (1568-1643) 1st Viscount of Ely. He held the office of Archdeacon of Glendalough, co. Wicklow between 1594 and 1643. and was appointed Knight in 1604. He was appointed Privy Counsellor (P.C.) [Ireland] in 1608, and held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) for King’s County between 1613 and 1615. He held the office of Lord Chancellor [Ireland] between 1619 and 1638. He was created 1st Viscount Loftus of Ely, King’s Co. [Ireland] on 10 May 1622.

In Cromwell’s time Drimnagh and its lands were granted to Lieutenant Colonel Philip Ferneley, a relation of Adam Loftus, who lived in the castle until his death in 1677. Some time in he 17th century the defensive nature of the castle was changed and it became a more comfortable residence with large mullioned windows to let in more light. A massive fireplace in the great hall was created around that time also.

In 1727 Walter Bagenal of Dunleckney, County Carlow, who had married Eleanor Barnewall, daughter of James of Bremore, County Meath, sold the castle to the John Fitzmaurice Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne, later generations of Petty and Petty-Fitzmaurice were the Marquesses of Lansdowne. This family leased the castle to various farmers throughout the 19th century.

The website tells us: “The undercroft was built as a storage room for food; it also doubled up as a refuge if the castle was attacked. The fireplace and bread and smoking oven are recreations of the kitchen that was here in the 19th century. The narrow stairs leading up to the next floor are unique in that they turn to the left, unlike most Norman castles which turn to the right.“

The restoration work started in June 1986 and over 200 workers were involved in the repair work, including stonemasons, woodcarvers, metal workers, plasterers, tilers and artists. The restoration of the the roof was inspired by Dunshoughly Castle in Fingal, and was built using Roscommon Oak which is renowned for its great durability and strength. The roof was constructed in the courtyard and was then raised onto the castle at a cost of 50,000 Punts (Irish £). The floor of the great hall was re-tiled with tiles taken from St. Andrews Church in Suffolk Street in Dublin. Some of the contemporary handmade tiles are replicas of medieval flooring, many decorated with Barnewall emblems.

The website tells us: “The great hall was originally an all-purpose living room/sleeping quarters in the 13th century. During the day tables and benches were placed in the centre of the floor for dining. At night straw or reed matting was laid on the floor and the occupants of the castle slept on this covering.“

The website tells us more about the history of the castle: “Drimnagh has seen its fair share of raids and attacks by the O’Toole Clans through the years and there is record of two of the Barnewalls of Drimnagh being killed in a skirmish near Crumlin. There are many undocumented raids and battles. In the 19th century, after these tumultuous times Drimnagh saw the arrival of industries like the paper mill at Landsdowne valley and other enterprises. Small Inns and lodges were built to house travellers on their way to Tallaght or further afield. Some of these are still in business today, such as the Red Cow and The Halfway House. Buildings of note in the area around the early 19th century were the Drimnagh Lodge, The Halfway House, Drimnagh Castle.

“After the 19th century we see more and more expansion out towards the Drimnagh area, but it was in the 20th century were we see housing estates and industrial estates springing up around Drimnagh. For more modern historical info please visit the Drimnagh Residents Associations excellent page on its history.“

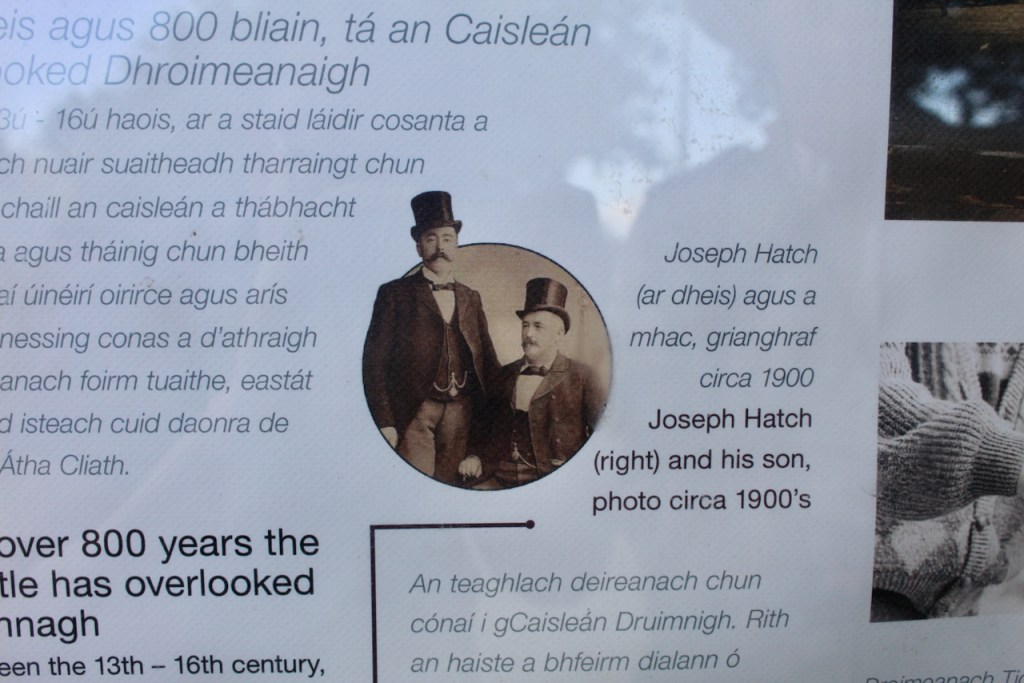

The website tells us of more recent inhabitants, the Hatch family:

“In the early 20th century, the castle and its surrounding lands found a new custodian in Joseph Hatch (born 1851), a prominent dairy man from 6 Lower Leeson Street. Serving as a dedicated member of Dublin City Council for Fitzwilliam Ward from 1895 to 1907, Joseph Hatch acquired the castle in the early 1900s to provide ample grazing land for his cattle.

“Passionate about preserving the heritage, Joseph Hatch undertook the restoration of the castle, transforming it into a charming summer retreat for his family. The castle also served as the picturesque venue for significant family milestones, including the celebration of Joseph and his wife Mary Connell’s silver wedding anniversary and the marriage of their eldest daughter, Mary, in 1910.“

“Following Joseph Hatch’s passing in April 1918, the castle became the legacy of his eldest son, Joseph Aloysius, affectionately known as Louis. Alongside his brother Hugh, Louis managed the family dairy farm and the accompanying dairy shop on Lower Leeson Street. Despite never marrying, Louis dedicated himself to the estate until his death in December 1951. Hugh, who married at the age of 60 in 1944, passed away in 1950.“

“The Hatch family continued to occupy Drimnagh Castle until the mid-1950s. Subsequently, Louis Hatch bequeathed the estate to Dr.P. Dunne, the Bishop of Nara. Dr Dunne, in turn, sold the castle (allegedly for a nominal sum) to the Christian Brothers. This transaction paved the way for the construction of the school that now proudly stands adjacent to the castle.“

The restoration work was completed in 1991 and was opened to the public by the then President of Ireland Mary Robinson. Since then the castle has hosted banquets, weddings, book launches and many more events. The castle is now maintained by a small group of dedicated people who keep the castle looking great for future generations to come.

There are further rooms upstairs.

The castle’s gardens have been developed, with a Parterre:

The website tells us: “A parterre is a formal garden construction on a level surface consisting of planting beds, edged in stone or tightly clipped hedging, and gravel paths arranged to form a pleasing, usually symmetrical pattern. It is not necessary for a parterre to have any flowers at all. French parterres originated in 15th-century Gardens of the French Renaissance. The castle parterre is a simple symmetrical design of four squares, divided into four triangular herb beds. The centre point of the squares feature a clipped yew tree while the centre point of each herb bed features a shaped laurel bay tree.

”One of the most important household duties of a medieval lady was the provisioning and harvesting of herbs and medicinal plants and roots. Plants cultivated in the summer months had to be harvested and stored for the winter. Although grain and vegetables were grown in the castle or village fields, the lady of the house had a direct role in the growth and harvest of household herbs.

”Herbs and plants grown in manor and castle gardens basically fell into one of three categories: culinary, medicinal, or household use. Some herbs fell into multiple categories and some were grown for ornamental use.” The website tells of some of these plants.

The gardens also have an alley of hornbeams:

“The common English “hornbeam tree” derives its name from the hardness of the wood, and was often used for carving boards, tool handles, shoe lasts, coach wheels, and for other uses where a very tough, hard wood is required. The plant beds either side of the trees, feature snowdrops, bluebells, tulips, daffodils, some ferns and hellebores.

”Hornbeam leaves are popular for their use in external compresses to stop bleeding. Their haemostatic properties also help in the quick healing of wounds, cuts, bruises, burns and other minor injuries. A yellow dye is obtained from the bark.“

After our tour inside, Peter brought us outside to show us more of the gardens surrounding the castle, and to have a look at the outer walls of the castle and the moat.