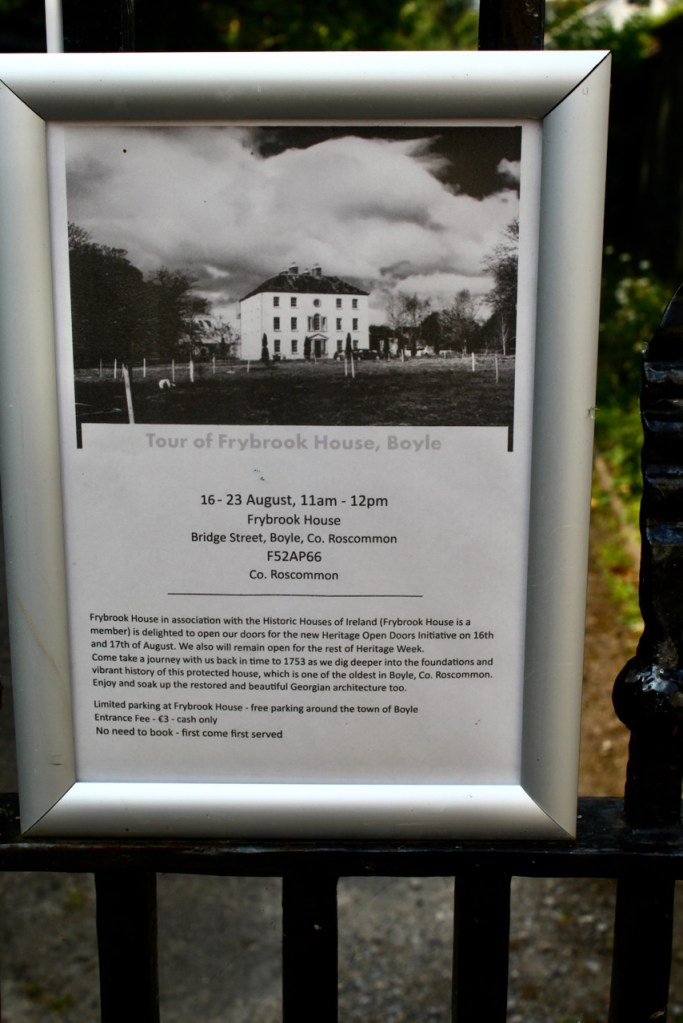

Frybrook House, County Roscommon

I am sad to see that Frybrook House in Boyle, County Roscommon, is once again advertised for sale, with Savills Estate Agent. We visited it recently during Heritage Week this year, 2025, and the owner, Joan, who showed us around gave no indication that she was planning to sell. It was previously sold in 2017, and since then, the owners spent time, effort, money and love renovating and decorating, preparing it for bed and breakfast accommodation. The thirty three windows took a year for a joiner to renovate, and the total renovation took about six years.

They decorated with flair, filling the house with cheeky art and historical elements, researching the history of the house.

Frybrook is a three storey five bay house built around 1753. [1] A pretty oculus in the centre of top storey sits above a Venetian window, above a tripartite doorcase with a pediment extending over the door and flanking windows. [2] Due to the proximity to the river the house is unusual for a Georgian house in not having a basement.

Henry Fry (1701-1786) built the house for his family and established a weaving industry. The website for the house tells us that in 1743 Lord Kingston, who at that time was James King (1693 – 1761), 4th Baron Kingston, invited Henry Fry, a merchant from Edenderry in County Antrim, to establish the business in Boyle. [3] The Barons Kingston lived in the wonderful Mitchelstown Castle in County Cork and were related to the Kings of King House in Boyle and of Rockingham House, the Baronets of Boyle Abbey (see my entry about King House, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/02/02/king-house-main-street-boyle-co-roscommon/.

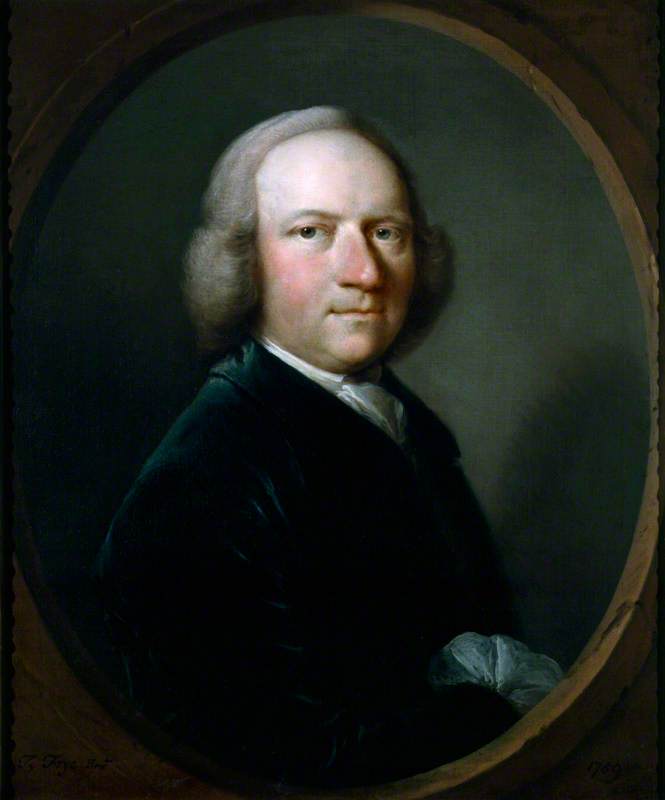

Henry Fry’s grandfather was from the Netherlands. Henry’s brother Thomas (1710–62) was an artist, recently featured in an exhibition at Dublin Castle.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that by 1736 Thomas Frye was in London and had become sufficiently established to be commissioned to paint the portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales, on the occasion of his becoming “the perpetual master of the Company of Saddlers.” Thomas also co-founded a porcelain factory, one of the earliest in England, and he experimented with formulas and techniques for making porcelain, obtaining a patent for his work.

Thomas’s brother Henry Fry (1701-1786) married twice; first to Mary Fuller, with whom he had several children, then after her death in childbirth, to Catherine Mills, with whom he had more children.

Joan brought us inside. The house has its original beautiful plasterwork and joinery, and the tiles in the hall too and staircase are probably original to the house.

There are formal rooms on both the ground floor and the first floor. They have more beautiful decorative plasterwork.

The house had been empty for about ten years before the owners bought it in 2018. Most of the fireplaces had disappeared and had to be replaced. There would have been a fine Adam chimneypiece at one time, which was sold by Richard Fry to a member of the Guinness family, our guide told us.

The half-landing features the Venetian window.

Upstairs there is another formal room with fine plasterwork and also timber carving in the window embrasures.

Further up the staircase is another beautiful piece of ceiling detail, a curved ceiling with weblike plasterwork detail, above a curved door frame.

Upstairs are the bedrooms. One in particular is gorgeously decorated with sumptuous colours and fittings and has a carved chimneypiece and jewel-like en suite. The owner asked us not to post photographs as it is the guesthouse piéce de resistance. I do hope the new owners, if it is sold, will maintain it as a guest house as it would be a lovely place to stay! Although it would also make a fabulous home for some lucky family. It has seven en-suite bedrooms.

Frybrook passed to Henry’s son, another Henry (1757-1847). He married Elizabeth Baker, daughter of William Baker of Lismacue, County Tipperary, a Section 482 property (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/02/10/lismacue-house-bansha-co-tipperary-section-482-accommodation/ ).

Robert O’Byrne tells us that “in 1835, Henry Fry of Frybrook and his relative, also called Henry Fry, of another house in the vicinity, Fairyhill, were founding members of the Boyle branch of the Agricultural and Commercial Bank (although this venture failed nationally after only a couple of years). Successive generations of Frys continued to live in the family home until the 1980s when, for the first time, it was offered for sale.” [4]

Another son of Henry Fry, Magistrate, (1701-1786) was Oliver (1773-1868), major of Royal Artillery, Freemason, Orangeman, and diarist. Our guide on the tour of the house read us an excerpt of his diary. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that in 1793 Oliver had to leave Trinity college to go home to help his brother Henry defend his house from the “Defenders.” The Defenders were a Catholic Agrarian secret society that originated in County Armagh in response to the Protestant “Peep o’ Day Boys.” The Defenders formed Lodges, and in 1798 fought alongside the United Irishmen. In later years they formed the “Ribbonmen.” The Peep o’ Day Boys carried out raids on Catholic homes during the night, ostensibly to confiscate weapons which Catholics under the Penal Laws were not allowed to own. [5] The Defenders formed in response, and oddly, grew to follow the structure of the Freemasons, with Lodges, secrecy and an oath swearing obedience to King George III. The Peep o’ Day Boys became the Orange Order.

The Defenders carried out raids of Protestant homes to obtain weapons. When Britain went to war with France in 1793, small Irish farmers objected to a partial conscription as they needed their young men for labour, which increased membership in the Defenders.

The Dictionary tells us about Oliver Fry:

“He was a member of the force of Boyle Volunteers that defeated a large group of Defenders at Crossna and subsequently defended the residence of Lord Kingston (1726–97) at Rockingham. During this latter skirmish he captured the leader of the Defenders, and was later presented with a commission in the Roscommon militia by Lord Kingston.”

Oliver served in the Royal Irish Artillery. The Dictionary of Irish Biography entry about him tells us more:

“In 1822 Fry wrote a retrospective account of his early life, and thereafter kept a very detailed diary. While some of the accounts of his military service were somewhat exaggerated, his diary remains an invaluable source of information on the major events of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including the agrarian disturbances of the 1820s–40s, the repeal movement, the cholera epidemic of 1831, and the Great Famine. Other more colourful events were also described, such as the visits of Queen Victoria, the Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851, and the Dublin earthquake of 1852. He died 28 April 1868 at his Dublin home, Pembroke House, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, and was buried at Mount Jerome cemetery.“

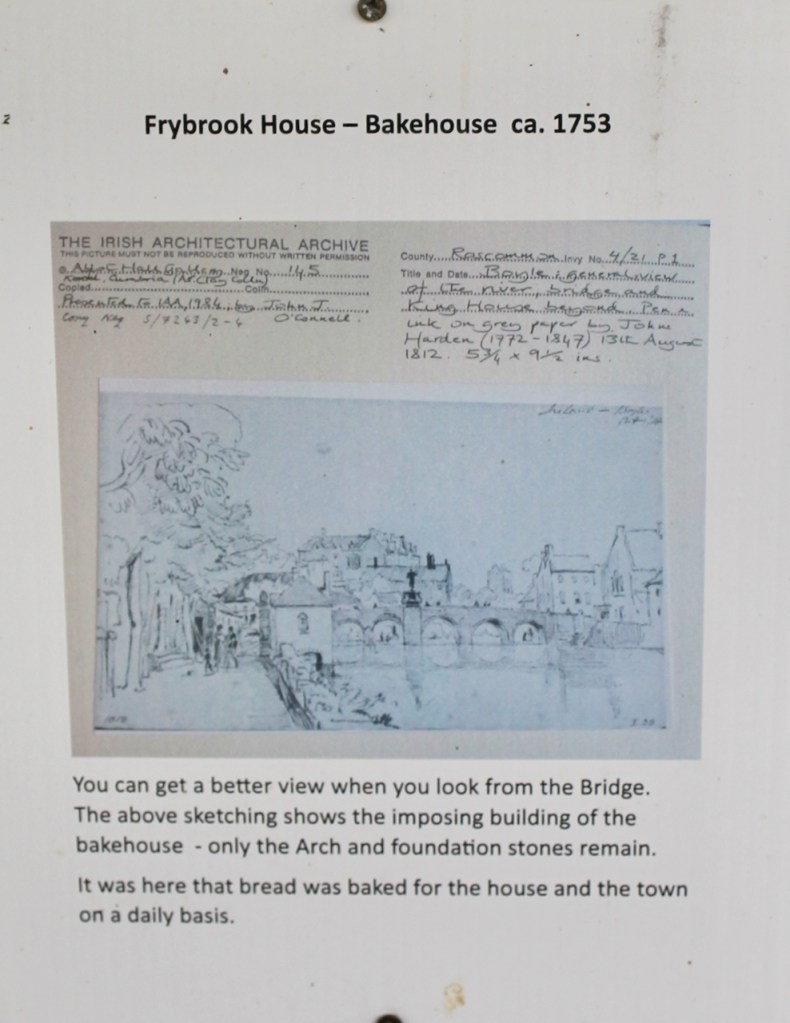

Despite the oppositional stance with Catholics, our guide told us that the family were generous in famine times, as evidenced by the Bakehouse, the remains of which are next to the driveway to the house. However, a bakehouse isn’t evidence that the family gave out the bread for free!

Further evidence of the Fry’s hospitality, Joan told us, are the “hospitality” stones on the piers at the entrance to the house.

The pier stones resemble worn pineapples. The only reference I can find to “hospitality stones” in a quick google search is that hospitality stones were like ancient admission tickets: stones with some marking on them given by someone to indicate that the bearer could produce the stone and receive hospitality in return. The stones on the entrance piers resemble worn pineapples. In the eighteenth century pineapples became a symbol of luxury, wealth and hospitality. A blog of the Smithsonian Museum tells us:

“The pineapple, indigenous to South America and domesticated and harvested there for centuries, was a late comer to Europe. The fruit followed in its cultivation behind the tomato, corn, potato, and other New World imports. Delicious but challenging and expensive to nurture in chilly climes and irresistible to artists and travelers for its curious structure, the pineapple came to represent many things. For Europeans, it was first a symbol of exoticism, power, and wealth, but it was also an emblem of colonialism, weighted with connections to plantation slavery...

“…the intriguing tropical fruit was able to be grown in cold climates with the development, at huge costs, of glass houses and their reliable heating systems to warm the air and soil continuously. The fruit needed a controlled environment, run by complex mechanisms and skilled care, to thrive in Europe. Pineapples, thus, became a class or status symbol, a luxury available only to royalty and aristocrats. The fruit appeared as a centerpiece on lavish tables, not to be eaten but admired, and was sometimes even rented for an evening.

“…The pineapple became fashionable in England after the arrival in 1688 of the Dutch King, William III and Queen Mary, daughter of James II, who were keen horticulturalists and, not incidentally, accompanied by skilled gardeners from the Netherlands. Pineapples were soon grown at Hampton Court. The hothouses in Great Britain became known as pineries. With its distinctive form, the cult of the pineapple extended to architecture and art. Carved representations sit atop the towers of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and other prominent buildings, perhaps an adaptation or reference to the pinecones used on ancient Roman buildings.“

“…During the 18th century, the pineapple was established as a symbol of hospitality, with its prickly, tufted shape incorporated in gateposts, door entryways and finials and in silverware and ceramics.” [6]

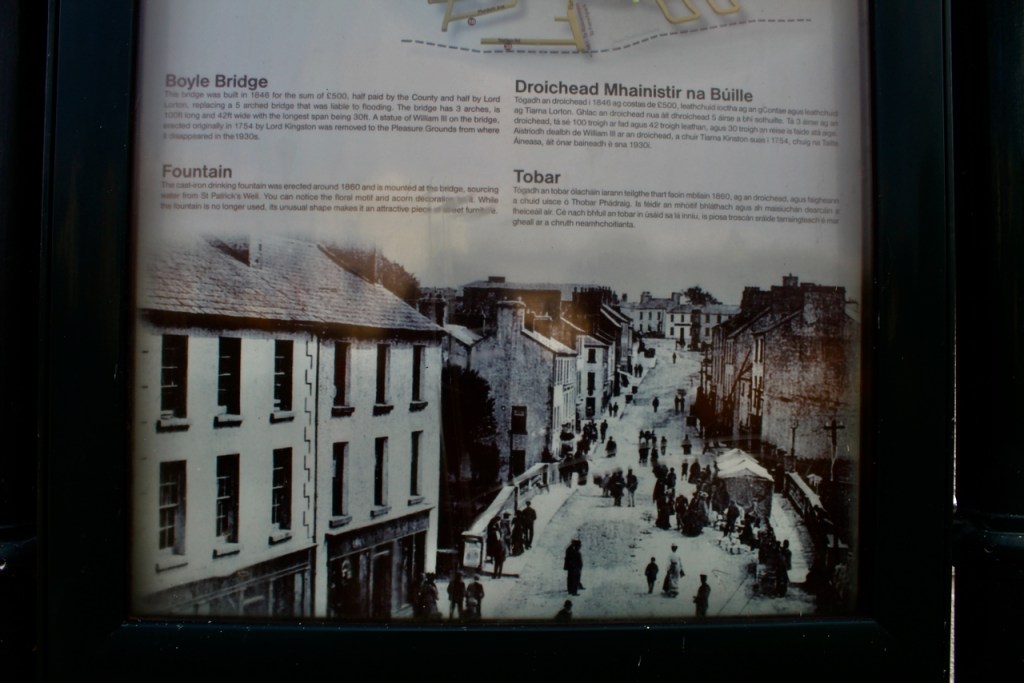

The lovely cafe in the gate lodge is situated on the river, next to the triple arch stone bridge over the River Boyle which was built in 1846 (or 1864, according to the National Inventory). [7]

The house’s website tells us:

“A bell was positioned on the roof of Frybrook house and it rang every day to invite the locals to dine in Frybrook, and when there was no room inside the house, tents were erected on the lawn.

“During the 1798 rising (‘Year of the French’) even the officers of the opposing French army were dining in the house.

“Frybrook House also supplied soup to the locals during the Great Famine (1845 to 1852), evidenced by a very large Famine Cauldron in the kitchen.“

I don’t know how it was that the Frys would host the French when Oliver was serving in the army fighting against the French! Perhaps this information is in Oliver’s diary. It would be a fascinating read. The Dictionary of Irish Biography gives a reference for his diary: William H. Phibbs Fry, Annals of the late Major Oliver Fry, R.A. (1909).

The bell may have been used to serve to tell the time for the weaving employees. The rope ran from the top of the house to the ground floor.

The weaving industry had 22 looms, our guide told us. Frybrook wasn’t a landed estate, and the owners did not make their money from having a large amount of land and tenants. The house had six acres. In later years the Fry family sold vegetables, and Lord Lorton established a market shambles for meat and vegetables.

Not all cauldrons were used to feed the public during the Famine. In the kitchen of the house there is a large cauldron that would have been used for washing clothes. The kitchen of Frybrook has many original features.

It has a Ben Franklin designed stove, which was invented to be a stove that was safe for children to be around.

The Famine in the 1840s hit Boyle hard. Information boards in King House tell us about Boyle in famine times. For the King family of Boyle, it was a time of trouble with tenants, as outlined in The Kings of King House by Anthony Lawrence King-Harmon.

Robert Edward King (1773-1854) joined the military and distinguished himself in the Caribbean. When he inherited Kingston Hall at Rockingham, Boyle, in 1797, he returned to Ireland and joined the Roscommon Militia and worked his way up to become a General. With Rockingham, however, came debt. In 1799 he married his first cousin, Frances Parsons Harman, daughter of his aunt Jane who had married Lawrence Parsons Harman (1749-1807), who owned the Newcastle Estate in County Longford. Robert worked hard to reduce the debt, and was a tough landlord, evicting many tenants.

In famine years, however, he lowered rents and provided work. The information boards in King House tell us that in the 1800s, Boyle residents suffered with poverty. One third of the population died of hunger and hundreds went to the workhouse. In the 1830s about 500 men, women and children were evicted from Lord Lorton’s estates around Boyle. Many were paid to emigrate to North America.

The Fry family would have been in the centre of such poverty and hardship, and it must have been a dreadful time. They remained in the town and survived.

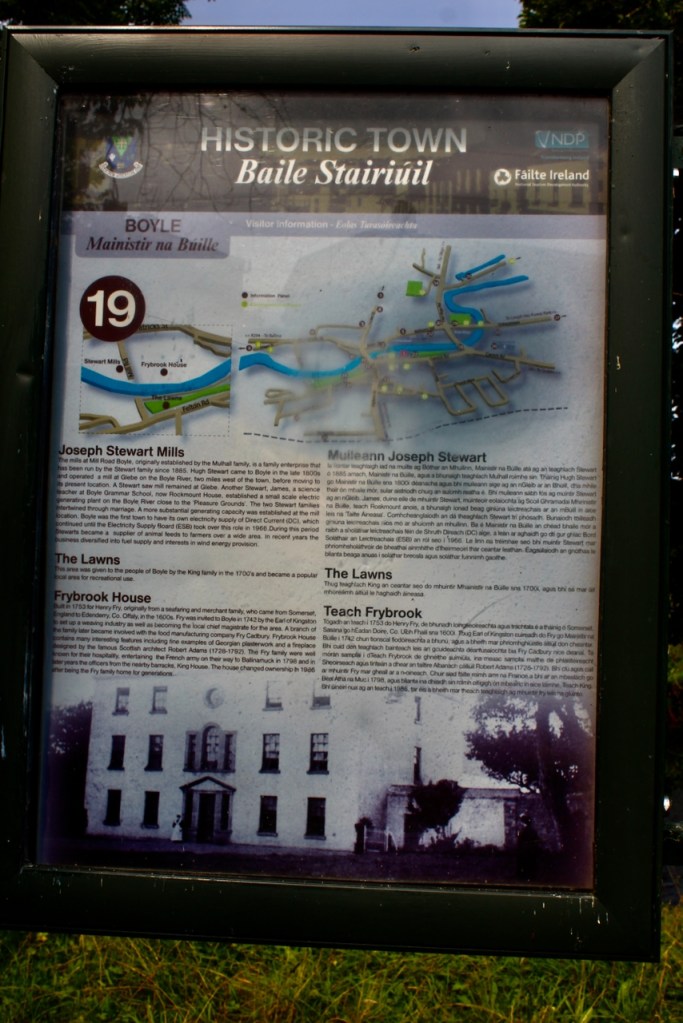

Joan told us that the Frys owned a mill, but the information board for the nearby mill does not mention Fry ownership. The current mill seems to have been built around 1810, according to the National Inventory, and the information board tells us that it was originally established by the Mulhall family and has been run by the Stewart family since 1885.

Thank you to Joan for the wonderful tour and for being so generous with her time. She and the owners deserve thanks for bringing Frybrook back so vibrantly to life.

[2] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978) Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[3] https://frybrook.ie/frybrooks-history/

[4] https://theirishaesthete.com/2023/10/23/frybrook/

[5] Brendan McEvoy (1986). The Peep of Day Boys and Defenders in the County Armagh. Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society.

[6] https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2021/01/28/the-prickly-meanings-of-the-pineapple/

[7] The Inventory says the bridge was built in 1864. https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/31804042/bridge-street-mocmoyne-boyle-co-roscommon