Open dates in 2026: May 1-31, June 1-5, 9-12, 16-19, 23-28, Aug 1-2, 15-23, 29-30, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student €8, child €4, under 4 years free, groups discount

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

We visited Larchill on a glorious sunny day in May 2022. The house has an excellent website explaining the fact that it is a ‘Ferme Ornée’ or Ornamental Farm and is the only surviving, near complete, garden of its type in Europe. It was created between 1740 and 1780. You may have seen the house recently in the television series “Blood” starring Adrian Dunbar.

The Ferme Ornée gardens of the mid 18th century were an expression in landscape gardening of the Romantic Movement. The National Inventory tells us that the house, ornamental farm yards and follies were built by Robert Watson, but it could have been for the previous owners, the Prentice family, a Quaker merchant family who lived in Dublin and at nearby Phepotstown and who owned the land of Larchill. According to the National Inventory, the farm yard was built around 1820, later than the house, which was built around 1790. [1] [2]

Robert Prentice leased Phepotstown in 1708 to grow flax for the production of linen and it seems that at this time he started to develop the land as a ‘Ferme Ornée.’ [3]

It was the current owners, Michael and Louisa de las Casas, who discovered the significance of the property, which had become overgrown and fallen into disrepair, due to a visit by garden historian Paddy Bowe, who was the first to realise that Larchill was a Ferme Ornée and an important ‘lost’ garden.

The website tells us about the idea of an ornamental farm:

“Emulating Arcadia, a pastoral paradise was created to reflect Man’s harmony with the perfection of nature. As is the case at Larchill, a working farm with decorative buildings (often containing specimen breeds of farm animal) was situated in landscaped parkland ornamented with follies, grottos and statuary. Tree lined avenues, flowing water, lakes, areas of light and shade and beautiful framed views combined to create an inspirational experience enabling Man’s spirit to rejoice at the wonder of nature.“

The owners continue the tradition of keeping specimen breeds with the long-horn cow, peacocks and quail. They used to be kept busy with tourists and children with an adventure area and collection of rare breeds of farmyard animal, but they no longer gear it toward such an audience.

The website continues: “At this time in Versailles, Marie Antoinette enjoyed extravagant pastoral pageants, housed specimen cattle in highly decorated barns, while she herself is said to have dressed as a milk maid complete with porcelain milk churns. Freed from the restrictions of the 17th century formal garden, the Ferme Ornée represented the first move towards the fully fledged landscape parkland designs of Capability Browne.“

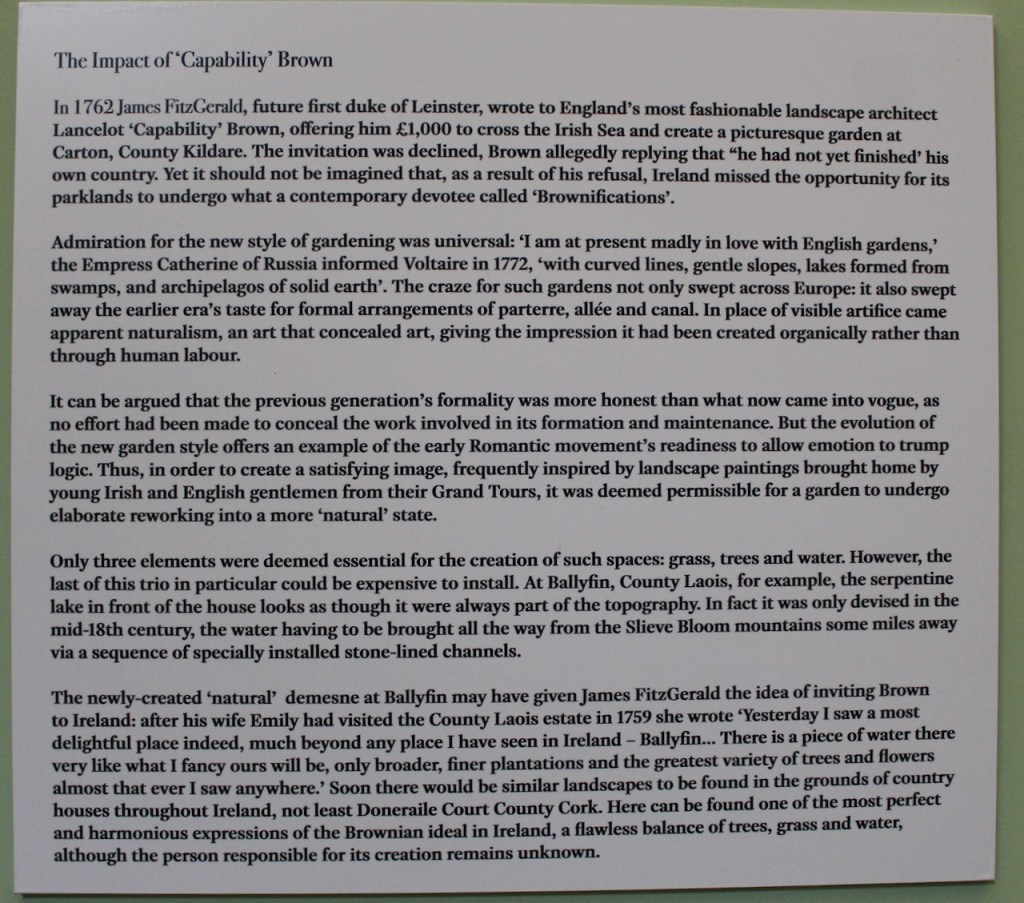

I recently visited the exhibition of “In Harmony with Nature: The Irish Country House Garden 1600-1900” at the Irish Georgian Society, curated by Robert O’Byrne. He describes the Romantic movement and landscape design of Capability Brown:

The Larchill website continues: “The Prentice family had trading connections throughout Europe and would have been aware of the new fashion in garden design: in particular the famous gardens of Leasowes and Woburn Farm in England. In Ireland the Prentice’s townhouse was adjacent to the home of Dean Swift in Dublin where he had developed his orchard and garden, ‘Naboth’s Vineyard.’ Dean Swift and his great friend Mrs Delaney (known today for her exquisite floral collages) were most closely associated in Ireland with knowledge of the new movement in garden design. Larchill was only 10 miles from Dangan Castle [now a ruin], often visited by Mrs Delaney, where from 1730 an extravagant 600 acres of land was embellished with a 26 acre lake, temples, statuary, obelisks and grottos by Richard Wellesley, Earl of Mornington and Grandfather of the Duke of Wellington [I think this was Richard Wesley (c.1690-1758), first Baron of Mornington. He was born Richard Colley but took the name Wesley when he inherited Dangan from his cousin Garret Wesley. [4] Mrs Delaney writes that he had a complete man-of-war ship on his lake!]. This is entirely contemporary with the Prentice’s period of garden development on their estate.“

Robert O’Byrne writes of Larchill in his blog and tells us more about the beginnings of the movement for “ornamental farms”:

“Despite its French name, the concept of the ferme ornée is of English origin and is usually attributed to the garden designer and writer Stephen Switzer.* [*Incidentally, Stephen Switzer was no relation to the Irish Switzers: whereas his family could long be traced to residency in Hampshire, the Switzers who settled in this country in the early 18th century had come from Germany to escape religious persecution.] His 1715 book The Nobleman, Gentleman, and Gardener’s Recreation criticized the overly elaborate formal gardens derived from French and Dutch examples, and proposed laying out grounds that were attractive but also functional: ‘By mixing the useful and profitable parts of Gard’ning with the Pleasurable in the Interior Parts of my Designs and Paddocks, obscure enclosures, etc. in the outward, My Designs are thereby vastly enlarg’d and both Profit and Pleasure may be agreeably mix’d together.’ In other words, working farms could be transformed into visually delightful places. One of the earliest examples of the ferme ornée was laid out by Philip Southgate who owned the 150-acre Woburn Farm, Surrey on which work began in 1727. ‘All my design at first,’ wrote Southgate, ‘was to have a garden on the middle high ground and a walk all round my farm, for convenience as well as pleasure.’ The fashion for such designs gradually spread across Europe as part of the adoption of natural English gardens: perhaps the most famous example of the ferme ornée is the decorative model farm called the Hameau de la Reine created for Marie Antoinette at Versailles in the mid-1780s. The most complete extant example of this garden type in Europe is believed to be at Larchill, County Kildare.” [5]

The Larchill website continues: “Thus there were many sources of reference for the Prentice family as they created their own pastoral paradise before falling on hard times and bankruptcy due to failure in their trading enterprises [around 1760]. The Ferme Ornée gardens were, as a result, leased separately from Phepotstown House and became known as Larchill after a boundary of Larch trees was planted around the farm and garden in the early 1800’s.“

The Watsons leased the property in 1790 and the farm manager’s house was upgraded with additions at this time (around 1780). (see [3])

The website Meath History Hub gives us more information about the inhabitants of Larchill:

“Richard Prentice, a haberdasher from The Coombe in Dublin occupied Larch Hill in the late eighteenth century. He may have established a Ferme Ornée at Larchhill and constructed the follies although they are generally dated to later. Mr. Prentice was declared bankrupt in 1790, owing ten thousand pounds to a Mr John Smith in Galway.

In 1790 the lease at Phepotstown was taken over by Thomas Watson. The Watson family were a Quaker family from Baltracey, Edenderrry. The house at Larch Hill may have been constructed at this time. Thomas died in 1822. His brother, Samuel Eves Watson [1785-1835], took a lease on Larchill when he married Margo Doyle in 1811. In 1820, Samuel E. Watson inherited half the estate of his uncle, Samuel Russell, in Hodgestown, Timahoe. This brought together four estates with a total area of 1,627 acres. When he died in 1836 his grandson, Samuel Neale [or was Samuel Neale his nephew, son of his sister Anna Watson?], got the estate but he had to take the name Watson in order to inherit. In 1837 Larch Hill, Kilmore, Kilcock was the residence of S.E. Watson. Its grounds were embellished with grottoes and temples. Samuel Neale Watson, as he was now known, married Susanna Davis in 1840 and lived mainly in Dublin. Samuel Neale Watson died in 1883. Seamus Cullen has researched the history of the Watson family.” [6]

The property is mainly notable for its follies, but the house is lovely too, an old Quaker farmhouse.

The yard is connected to the house.

We heard the distinctive cry of a peacock and one strutted in the yard. Guinea fowl ran around in a large gang, alerting owner Michael to our visit.

He greeted us outside the barns, and brought us through the house. The house was built around 1780, and entering the back door, one can see the age – one senses it in the walls in the back hallway, which are not as smooth and straight as in a modern house, and they seem to sit more firmly in the ground. The ceilings are also higher.

Although a farmhouse, it has lovely coving in the drawing room, a ceiling rose and marble fireplace.

The Larchill website continues, about the early 1800s: “It was after this time that the local Watson family leased Larchill and the famous connection was made, to this day, between Robert Watson, Master of the Carlow and Island Hounds and the Fox’s Earth folly. Although the Fox’s Earth would certainly predate the Watson’s tenure at Larchill [he died in 1908], and the fact that Robert Watson was only a distant relative of the Watsons at Larchill, still it is believed that the Fox’s Earth was constructed in response to Robert Watson’s guilt at having killed one too many foxes and his fear of punishment in reincarnation as a fox.”

The Larchill website the National Inventory tell us that according to folklore the Fox’s Earth was created by Mr Robert Watson, a famous Master of Hounds in the 18th Century who feared punishment through re-incarnation as a fox, having killed one too many foxes during his hunting career. References I have found refer to the 19th century Robert Watson who was master of the hunt. [7] I’m not sure if there was an 18th Century Robert Watson to whom the Larchill website refers. Robert Watson (1821-1908) of the Hunt lived at Ballydarton, County Carlow. [8] Maybe he influenced his Watson relatives who lived at Larchill to ensure that the odd structure would act as a “fox’s earth” in case he was reincarnated as a fox! Whatever the case, it makes a great story! Ideas of reincarnation were, the Larchill website tells us, being explored at this time through the Romantic movement as established Christian doctrine came into question. It is feasible that there was every intention to create a Fox’s refuge with the design of this folly.

The “Fox’s Earth” folly structure, the website tells us, comprises an artificial grassed mound within which is a vaulted inner chamber with gothic windows and entrance. A circular rustic temple surmounts the mound. Externally it is reminiscent of an ice house.

Leading away, on either side from the vaulted interior, are tunnels disappearing into the mound. These ‘escape’ tunnels seem to corroborate the story of this being a “Fox’s Earth”, a refuge and escape route for a fox pursued by the hunt.

The National Inventory calls it a Mausoleum: “Mausoleum and folly, built c.1820. Comprising three-bay single-storey dressed limestone façade set into artificial mount, with rustic temple set on the mount. Pointed arch openings to three-bay façade. Rubble stone walls to site, with circular profile piers. Circular profile temple, comprising six columns, capped with dome. Rubble stone bridge to the site.” [9]

Another possibility that Michael told us is that the temple is a Temple of Venus. Inside its tunnels are in the shape of a woman’s reproductive system, with a womb and fallopian tubes. It could have been a sort of temple to fertility.

The Larchill website continues: “Although described in the notes to the 1836 Ordnance Survey as ‘the most fashionable garden in all of Ireland’ over the decades knowledge of the Larchill Ferme Ornée faded. The parkland returned to farmland, the lake was drained and the formal garden was lost and used to graze sheep. Although the follies became semi derelict and obscured by undergrowth and trees, the mystery and beauty of Larchill was still recognised. Folklore stories of hauntings and the ‘strange’ nature of Larchill ensured its continued notoriety.

The Meath History Hub tells us: “The Barry family resided at Larchhill from the 1880s until 1993. Christopher and Maria Barry donated the Stations of the Cross to Moynalvey church. Christopher died before 1911 leaving Maria a widow.” (see [6])

In 1994 the de Las Casas family acquired Larchill. Four years of restoration followed with the aid of a grant from the Great Gardens of Ireland Restoration Program and a FAS Community Employment Project.

In recognition of the quality and sensitivity of the restoration program Larchill Arcadian Garden has been awarded the 1988 National Henry Ford Conservation Award, the 1999 ESB Community Environment Award and the 2002 European Union Environmental Heritage Award.

We then went outside to explore. Michael gave us a map to follow around the grounds. First he showed us the ingenious mechanism in the ornamental gate:

Before we walked the circumference of the field and lake, Michael showed us to the walled garden behind the house. On the way we passed a statue of Flora:

The ornamental dairy used to have Dutch tiles but unfortunately a previous owner removed them! Ornamental dairies were common in ornamental farms, and were places where products of the dairy could be sampled if not actually made there.

At the north west corner of the restored Walled Garden the Shell Tower is a three storey, battlemented tower with single arched Gothic windows.

The tower, called a “Cockle Tower,” is decorated with shells, but unfortunately it needs to be stabilised before one could safely enter. I did manage to see the inside of the shell tower by looking through a window. We saw a shell house in Curraghmore in County Waterford, and Mary Delany is famous for her shell work. There is also one nearby at Carton Estate.

The website tells us that in the case of the Larchill Shell Tower, where lower rooms are decorated with shells laid in geometric patterns, the shells appear to be mostly native varieties, many are cockles with some exotic exceptions such as conches – perhaps sourced via the trading connections of the 18th century Prentice family who created the Ferme Ornée at Larchill.

After we explored the walled garden, we set off to see the follies dotted around the lake. On the lake itself are two follies: the Gibraltar and the round temple. A previous owner had drained the lake but the current owners reinstated it, as water is an essential element of an ornamental farm, creating a romantic landscape. We learned a charming new word: marl clay lines the bottom of the lake. To prepare the clay before the lake was filled with water, the land underwent the process of “puddling.” This is letting sheep loose on the clay to walk it into the ground.

The ditch of the ha-ha contained a fish pond, and this flowed to an eel pond. Fish farming would have been a lucrative practice.

Gibraltar: This is a castellated miniature fort with circular gun-holes and five battlemented towers situated on one of two islands within the lake. It would have been constructed just shortly before, or at the same time as, the famous defense by the British of their garrison on Gibraltar against the Spanish during the ‘Great Siege’ of 1779 to 1783. The siege, which lasted nearly three and half years through starvation and repeated onslaughts by the Spanish, was impressive news at the time and must have motivated the naming of the fortress as Gibraltar.

There is a similar “Gibraltar” tower in Heathfield Park Estate in East Sussex. In 1791 Francis Newbery bought Bailey Park, an estate in East Sussex, which he renamed the Heathfield Park Estate. One of his first projects was to create a memorial to the former owner of the estate, George Augustus Eliot, who had been Governor at Gibraltar during the lengthy ‘Great Siege’ by the Spanish and French of 1779-1783. In 1787 Eliot was created Lord Heathfield of Gibraltar in recognition of his service to his country, and his death in 1790 had been marked by long eulogies in the press. The tower was later sketched by Turner as part of his commission to provide illustrations for Cooke’s Views in Sussex. [11]

However the fortress at Larchill was much more a source of pleasure and entertainment, the Larchill website tells us, with stories of mock battles across the lake.

There are more follies that one comes across as one walks around the estate.

The website tells us about the Lake Temple: it “is a circular island building in the lake to the west of Gibraltar. The outer wall has decorative recesses and the internal circle of columns surrounds a well-like central core.

There is evidence that the columns may have originally been partially roofed so as to direct rainwater into the well itself. It is possible that the design was intended to emulate the plunge pool baths of Ancient Rome, such as the famous pool at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.”

There used to be a causeway out to the island temple. Another theory is that the well and round temple could have been part of a sham Druidic temple. Tim Gatehouse writes of a Grand Lodge of Irish Druids in the 1790s, whose summer activities included visits to members’ estates. (see [3])

It was lovely to wander around Larchill on such a sunny day. The owners have done us a great service to resurrect the beauty of an ornamental farm.

[3] Gatehouse, Tim. “Larchill: a rediscovered Irish garden and its Australian cousin,” Australian Garden History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (July 2017), pp. 15-20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26391590?read-now=1&seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2018/09/17/larchill-gardens/

[7] https://carlow-nationalist.ie/2015/01/30/carlow-horsemen-celebrate-200-years-of-fox-hunting/

[8] The Watsons of Kilconnor, County Carlow, 1650 – present by Peter J F Coutts and Alan Watson https://books.google.ie/books?id=-OiJDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA188&lpg=PA188&dq=watson+%2B+larchill&source=bl&ots=f6EB7C366O&sig=ACfU3U3ar4INf4CGknDXjzVASjy1rlq0Ow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjvlpXZuqX5AhWCWMAKHTpzA9cQ6AF6BAgwEAM#v=onepage&q=watson%20%2B%20larchill&f=false

[11] https://thefollyflaneuse.com/gibraltar-tower-heathfield-park-east-sussex/

[12] Lake Temple: https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/14404911/larch-hill-larch-hill-demesne-phepotstown-co-meath

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com