On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Kerry:

1. Derrynane House, Caherdaniel, County Kerry – OPW

2. Derreen Gardens, Lauragh, Tuosist, Kenmare, Co. Kerry – section 482, garden only

3. Kells Bay Garden, Kells, Caherciveen, County Kerry – garden only

4. Killarney House, County Kerry

5. Knockreer House and Gardens, County Kerry

6. Listowel Castle, County Kerry – OPW

7. Muckross House, Killarney, County Kerry – open to visitors

8. Ross’s Castle, Killarney, County Kerry

9. Staigue Fort, County Kerry

Places to visit in County Kerry:

1. Derrynane House, Caherdaniel, Kerry – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/11/07/office-of-public-works-properties-in-munster-counties-kerry-and-waterford/

2. Derreen Gardens, Lauragh, Tuosist, Kenmare, Co. Kerry, V93 D792 – section 482, garden only

https://www.derreengarden.com/

Open dates in 2026: all year, 10am-6pm

Fee: adult €12, child €6, family ticket €45 (2 adults & all accompanying children under18) season tickets from €40

Concession discounts available for large groups

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/07/derreen-gardens-lauragh-tuosist-kenmare-co-kerry/

The website tells us: “A beautiful 19th century woodland garden with paths winding through rare tropical plants and opening onto sea views.

“Set on a peninsula at the head of Kilmackillogue Harbour and surrounded by the Caha Mountains, the garden at Derreen covers 60 acres.

“A network of winding paths passes through a mature woodland garden laid out 150 years ago with subtropical plants from around the world and incomparable views of the sea and mountains.“

3. Kells Bay Garden, Kells, Caherciveen, Co Kerry, V23 EP48 – garden only

In 2026 this property is no longer on the Revenue Section 482 listing. See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/13/kells-bay-house-garden-kells-caherciveen-county-kerry/

The website tells us: “Kells Bay Gardens is one of Europe’s premier horticultural experiences, containing a renowned collection of Tree-ferns and other exotic plants growing in its unique microclimate created by the Gulf Stream. It is the home of ‘The SkyWalk’ Ireland’s longest rope-bridge.“

4. Killarney House, County Kerry – part of park

https://killarney.ie/listing/killarney-house-gardens/

Originally called Kenmare House. The stable block of Kenmare House was converted in 1830 into this house. The original Kenmare House was built in 1726 and was demolished in 1872 by Valentine Augustus Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare. The succeeding house, called Killarney House, and was accidentally destroyed by fire in 1913 and never rebuilt; instead, in 1915 the stable block of the original Kenmare House was converted into the present Killarney House, although the Brownes called it Kenmare House.

John McShain, renowned architect and building contractor, acquired Killarney House, the former home of the Earls of Kenmare, in 1956. After the death of McShain’s wife, Mary, in 1998, the stately house, and its lavish gardens were sold to the State with the proviso that the property would be incorporated into the neighbouring Killarney National Park. The McShains were allowed to live in the house for the remainder of their lives, and they remodelled extensively. When Mrs. McShain died in 1998 the house reverted to the state. It sat empty and became derelict, but in 2011 restoration was begun. The gardens are open to the public and at some stage, the house also will be opened up.

5. Knockreer House and Gardens, County Kerry – part of park, Education centre

https://www.discoverireland.ie/kerry/knockreer-house-and-gardens

“Killarney National Park Education Centre is based in Knockreer House, the last of the Kenmare mansions. The centre is situated on a hill close to the town of Killarney and has spectacular views over the National Park.

“We provide a range of specialist courses linked directly to the curriculum, using the diverse habitats of Killarney National Park as an outdoor classroom. We work with groups from all backgrounds, ages and abilities, including primary schools, post-primary schools, third level institutions, tour groups and youth groups. We also provide facilities and programmes for the general public and the corporate sector.“

The website tells us:

“Found in County Kerry’s Killarney National Park, Knockreer House and Gardens are within walking distance of Killarney Town. The area includes a circular walk with excellent views of the Lower Lake.

“The Knockreer section of Killarney National Park is within walking distance of Killarney Town, County Kerry. This area was formerly part of the Kenmare Estate, which was laid out by Valentine Brown, the third Viscount of Kenmare. Deenagh Lodge Tearoom dates back to 1834 and was the gate lodge of the Kenmare Estate. The tearoom is a popular haunt with locals and visitors after a stroll in the park. It is located just inside Kings Bridge across from St Mary’s Cathedral.

“Knockreer House, a short walk up the hill, is the Killarney National Park Education Centre and is built on the site of the original Killarney House, which was destroyed by fire in 1913. The circular walk is signposted and offers excellent views of the Lower Lake. On the circular walk there is a pathway off to the right that leads up to the viewing point on top of the hill, which provides a wonderful panorama of the surrounding countryside.“

6. Listowel Castle, County Kerry – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/11/07/office-of-public-works-properties-in-munster-counties-kerry-and-waterford/

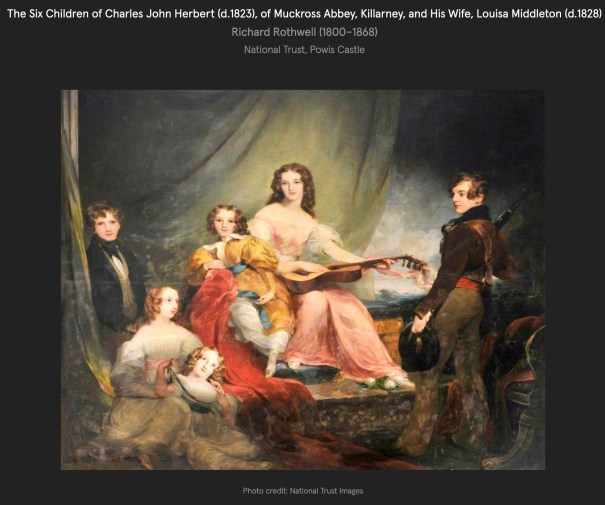

7. Muckross House (or Muckruss), Killarney, County Kerry – open to the public

“This nineteenth century Victorian mansion is set against the stunning beauty of Killarney National Park. The house stands close to the shores of Muckross Lake, one of Killarney’s three lakes, famed world wide for their splendour and beauty. As a focal point within Killarney National Park, Muckross House is the ideal base from which to explore this landscape.

“Muckross House was built for Henry Arthur Herbert and his wife, the water-colourist Mary Balfour Herbert. This was actually the fourth house that successive generations of the Herbert family had occupied at Muckross over a period of almost two hundred years. William Burn, the well-known Scottish architect, was responsible for its design. Building commenced in 1839 and was completed in 1843.

“Originally it was intended that Muckross House should be a larger, more ornate, structure. The plans for a bigger servants’ wing, stable block, orangery and summer-house, are believed to have been altered at Mary’s request. Today the principal rooms are furnished in period style and portray the elegant lifestyle of the nineteenth century landowning class. In the basement, one can imagine the busy bustle of the servants as they went about their daily chores. “

“During the 1850s, the Herberts undertook extensive garden works in preparation for Queen Victoria’s visit in 1861. Later, the Bourn Vincent family continued this gardening tradition. They purchased the estate from Lord and Lady Ardilaun early in the twentieth century. It was at this time that the Sunken Garden, Rock Garden and the Stream Garden were developed.“

8. Ross’s Castle, Killarney, County Kerry – OPW

See my OPW write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/11/07/office-of-public-works-properties-in-munster-counties-kerry-and-waterford/

9. Staigue Fort, County Kerry – ruin

The following website gives us information about this ancient impressive fort: https://voicesfromthedawn.com/staigue-fort/

It tells us:

“Constructed entirely without mortar, Staigue cashel encloses an area of 27.4 m (90 ft) in diameter, with walls as tall as 5.5 m (18 ft) and a sturdy 4 m (13 ft) in thickness. It has one double-linteled entrance, a passageway 1.8 m (6 ft) long. In the virtual-reality environment (above) click the hotspots to proceed to the fort’s interior. It is similar in construction to the Grianan of Aileach in Co. Donegal, and was possibly constructed in the same period of the Early Medieval period (approximately fifth to eleventh century CE). The fort is surrounded by a large bank and ditch, most evident on its northern side. This may have been a part of Staigue’s defenses, or it may be a prehistoric feature that pre-dates the construction of the stone fort.“

The website continues: “In 1897 T.J. Westropp reported that the local peasantry called the building Staig an air, which he translated as “Windy House, or “Temple of the Father,” or “The Staired Place of Slaughter.” These different translations may inspire distinctly different conjectures about the builders of Staigue. It has been described as both a temple or an observatory, and has been attributed to many different cultures in the past, such as Druids, Phoenicians, Cyclopeans, and Danes. But it was, of course, built by the “Kerrymen of old.”

“The sign at the site explains that Staigue “was the home of the chieftain’s family, guards and servants, and would have been full of houses, out-buildings, and possibly tents or other temporary structures.” The illustration from this sign is in the gallery below. Cashels, of which Staigue is an impressive and probably high-status example, were enclosed and defendable farmsteads of the Irish Early Medieval period. They housed an extended family and, in high-status examples, their retinue. However archaeologist Peter Harbison was unable to explain why the ancient architects would have created so many (10) sets of X-shaped stairs climbing up the inner face of the wall to its ramparts.“

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com