Howth Castle, Dublin

My friend Gary and I went on a tour of Howth Castle in Dublin during Heritage Week in 2025. You can arrange a tour if you contact the castle in advance, see the website https://howthcastle.ie

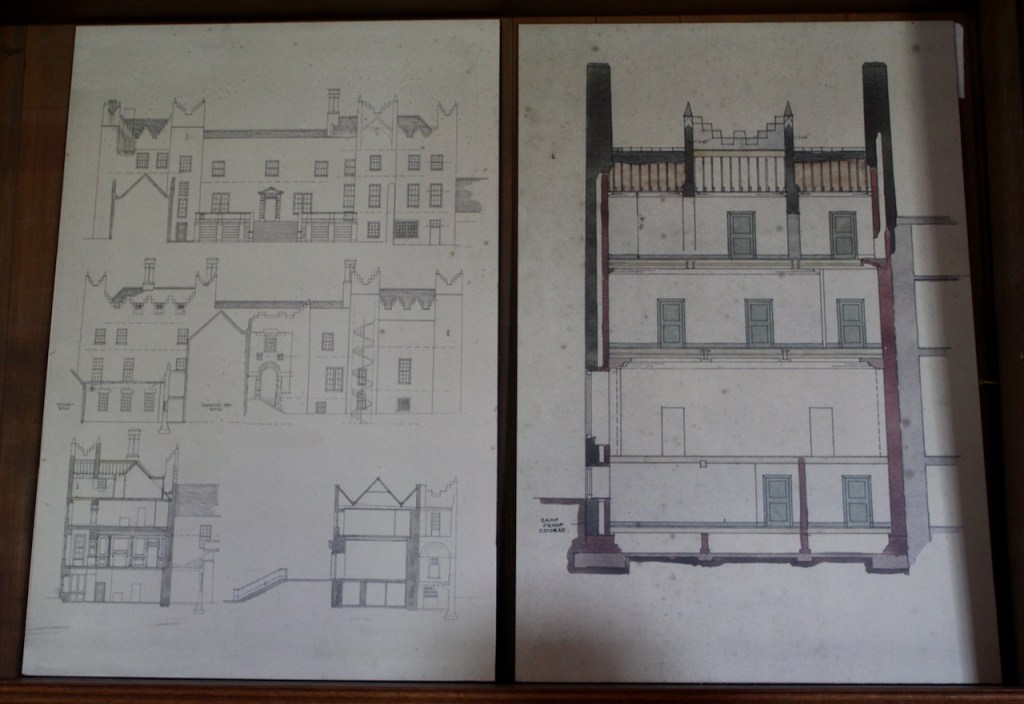

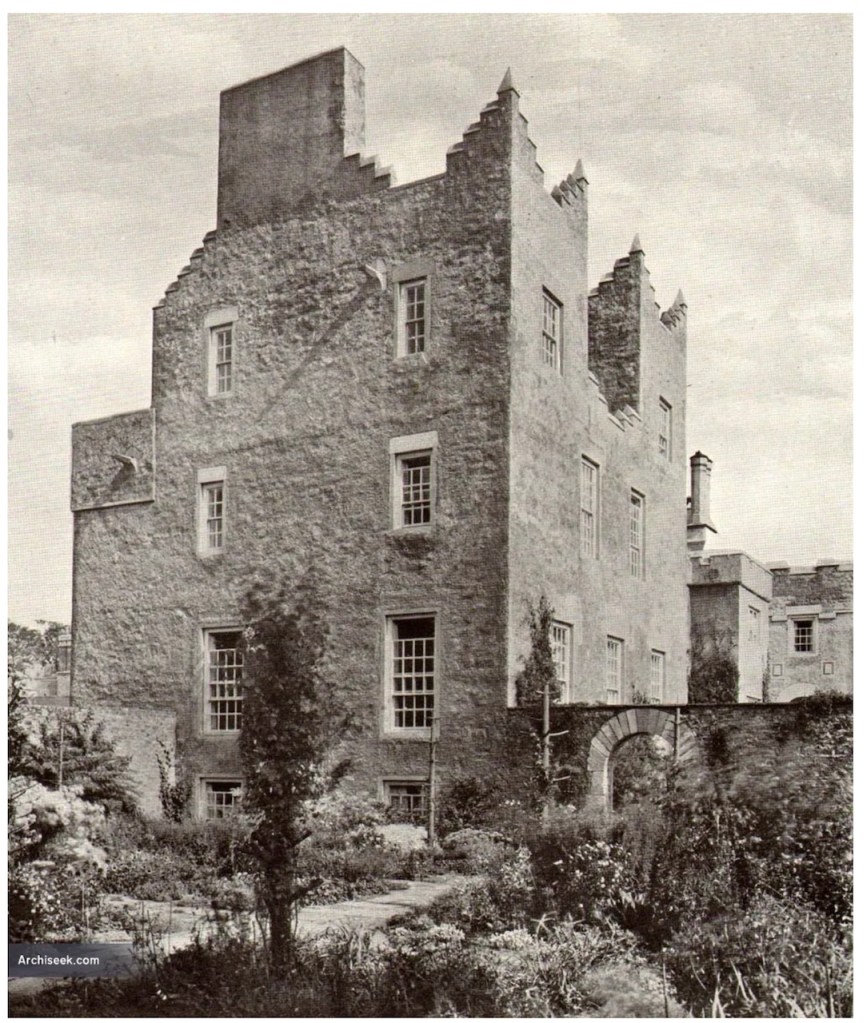

I envy historian Daniel, our tour guide, as he lives in the castle! Mark Bence-Jones describes the castle as a massive medieval keep, with corner towers crenellated in the Irish crow-step fashion, to which additions have been made through the centuries. [1]

Timothy William Ferres tells us that the current building is not the original Howth Castle, which was on the high slopes by the village and the sea. [2]

Until recently, the castle was owned by the Gaisford-St. Lawrence family. Irish investment group Tetrarch who purchased the property in 2019 plan to build a hotel on the grounds. It had been owned by the same family, originally the St. Lawrences, ever since it was built over eight hundred years ago. Over the years, wings, turrets and towers were added, involving architects such as Francis Bindon (the Knight of Glin suggests he may have been responsible for some work around 1738), Richard Morrison (the Gothic gateway, and stables, around 1810), Francis Johnson (proposed works for the 3rd Earl of Howth), and Edward Lutyens (for Julian Gaisford-St. Lawrence).

Timothy William Ferres tells us that the St. Lawrence family was originally the Tristram family. Sir Almeric Tristram took the name St. Lawrence after praying to the saint before a battle which took place on St. Lawrence’s Day near Clontarf in Dublin. Sir Almeric landed in Howth in 1177. After the battle he was rewarded for his valour in the conflict with the lands and barony of Howth. [see 2]

In an article in the Irish Times on Saturday August 14th 2021, Elizabeth Birthistle tells us that a sword that is said to have featured in the St. Lawrence’s Day battle is to be auctioned. A “more sober assessment” of the Great Sword of Howth, she tells us, dates it to the late 15th century. Perhaps, she suggests, Nicholas St. Lawrence 3rd Baron of Howth used it in 1504 at the Battle of Knockdoe. The sword is so heavy that it must be held with two hands. It is first recorded in an inventory of 1748, and is described and illustrated in Joseph C Walker’s An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish. [3]

Almeric went on to fight in Ulster and then Connaught. In Connaught, he was killed by the O’Conor head of the province, along with his thirty knights and two hundred infantry. He left three sons by his wife, a sister of John de Courcy, Earl of Ulster. The eldest son, Nicholas Fitz Almeric, relinquished his father’s Ulster conquests to religious houses, and settled in Howth. [see 2]

The first construction on the site would have been of wood.

The family coat of arms depicts a mermaid and a sea lion. The mermaid is often pictured holding a mirror. There is a coat of arms on the wall of the front of the castle which was probably moved from an older part of a castle. The Howth Castle website tells us:

“A mermaid is one of the supporters of the St. Lawrence family coat of arms, alongside a sea lion. The mermaid is often portrayed holding a small glass mirror. According to legend, the mermaid was once Dame Geraldine O’Byrne, daughter of The O’Byrne of Wicklow. She fell victim to dark magic at Howth Castle and was transformed into a mermaid. One item she left behind in her bedroom was a small glass mirror. The tower she slept in was from then always known as the ‘Mermaid’s Tower’. “

An article in the Irish Times tells us that there was a tryst between Dame Geraldine O’Byrne and Tristram St. Lawrence which left the Wicklow woman heartbroken and shamed, so she transformed into a mermaid. It is said her wails of melancholy are still carried through the winds at night near the Mermaid’s Tower on the estate. [3]

The Howth Castle website tells us that:

“One Christmas, Thomas St. Lawrence, Bishop of Cork and Ross [(1755–1831), son of the 1st Earl, 15th Baron of Howth] returned to Howth Castle to find that the family had gone to stay with Lord Sligo for the holiday season. Bishop St. Lawrence was left alone in the cold and dark castle with just a housekeeper for company and his ancestors glaring at him from the portraits in the dark hallways. The housekeeper put him to bed in the ‘Mermaid’s Tower’. His room was described as if ‘designed as the locus in quo for a ghost scene. Its moth-eaten finery, antiquated and shabby – -its yellow curtains, fluttering in the air…the appearance of the room was enough to make a nervous spirit shudder.’

“He was suddenly and violently awoken in the night by the feeling of a cold, wet hand clasping his wrist and a cold hand covering his mouth. He made one large leap from his bed, lit his candle and there he found not a sinner in the room with him but one bloody yellow glove lying on his bed. Was he visited in the night by the mermaid?”

I’m confused about Barons of Howth as different sources number the Barons differently. I will follow the numbering used on The Peerage website, which refers to L. G. Pine, The New Extinct Peerage 1884-1971: Containing Extinct, Abeyant, Dormant and Suspended Peerages With Genealogies and Arms (London, U.K.: Heraldry Today, 1972), page 150. According to this, Christopher St. Lawrence (died around 1462) was 1st Baron Howth. He held the office of Constable of Dublin Castle from 1461.

The oldest surviving part of the castle is the gate tower in front of the main house. It dates to around 1450, the time of the 1st Baron Howth.

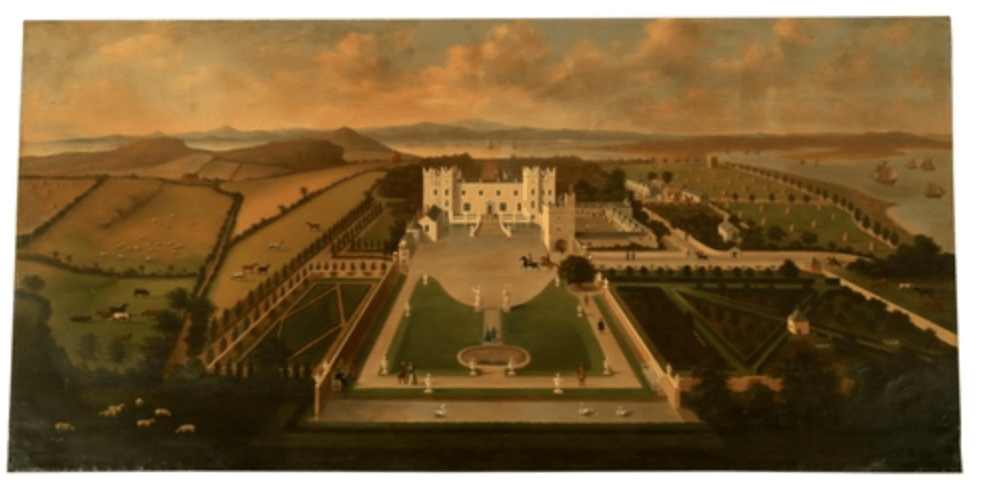

The Howth Castle website tells us that the Keep, the tower incorporated into the castle, also dates from the mid fifteenth century. Unfortunately I have misplaced the notes I took on my visit to the castle. Daniel pointed out the various parts of the castle as we stood on the balustrade looking out into the courtyard, telling us when each part was built. From the photograph of the painting above, the Keep is the large tower on the left of the front door, and the Gate House is slightly to the front of the building to the right. Traces remain in the gardens of the wall and turrets, which would have enclosed the area. You can’t fully see the keep from the front of the house.

Christopher’s son Robert St. Lawrence (d. 1486) 2nd Baron Howth served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, after first serving as “Chancellor of the Green Wax,” which was the title of the Chancellor of the Exchequer of Ireland. He married Joan, second daughter of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, so by marriage, Timothy William Ferres tells us, Lord Howth’s descendants derived descent from King Edward III, and became inheritors of the blood royal. [see 2]

Nicholas St. Lawrence (d. 1526) was 3rd Baron Howth according to the Dictionary of Irish Biography. He also served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland. He married three times. The first bride was Janet, daughter of Christopher Plunkett 2nd Baron Killeen. We came across the Plunketts of Killeen and Dunsany when we visited Dunsany Castle in County Meath.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that when Lambert Simnel came to Ireland in 1487 and was crowned as King Edward VI in Christchurch catheral in Dublin, Nicholas the 3rd Baron remained loyal to King Henry VII. [4] In 1504, as mentioned earlier, the 3rd Baron Howth played a significant role at the battle of Knockdoe in County Galway, where the lord deputy, 8th Earl of Kildare, defeated the MacWilliam Burkes of Clanricard and the O’Briens of Thomond. [see 4]

The family were well-connected. The third baron’s daughter Elizabeth married widower Richard Nugent, 3rd Baron Delvin, whose first wife had been the daughter of Gerald Fitzgerald 8th Earl of Kildare.

The son and heir of the 3rd Baron, Christopher (d. 1542), served as Sheriff for County Dublin. Christopher the 4th Baron was father to the 5th, Edward (d. 1549), 6th (Richard, d. 1558 and married Catherine, daughter of the 9th Earl of Kildare, but they had no children) and 7th Barons of Howth.

The Hall, which is the middle of the front facade, was added to the side of the Keep in 1558 by Christopher, who is the 20th Lord of Howth according to the Howth Castle website, or the 7th Baron. He was also called “the Blind Lord,” presumably due to weak eyesight. The 1558 hall is now entered by the main door of the Castle.

Christopher St. Lawrence (d. 1589) 7th Baron Howth was educated at Lincoln’s Inn, along with his two elder brothers, the 5th and 6th barons. Christopher entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1544 and was still resident ten years later in 1554. That year he was threatened with expulsion from Lincoln’s Inn for wearing a beard, which indicates, Terry Clavin suggests in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, a rakish side to his personality. He inherited his family estate of Howth and the title on the death of his brother Richard in autumn 1558 and was sworn a member of the Irish privy council soon afterward. [5]

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that between December 1562 and February 1563 the 7th Baron represented Thomas Radcliffe 3rd Earl of Sussex’s views on the government of Ireland to Queen Elizabeth. [5]

The Dictionary tells us that from 1570 onward the 7th Baron Howth ceased to play an active role in the privy council and became increasingly estranged from the government. By 1575, concerned about his loyalty, the government briefly imprisoned him, following the arrest of his close associate Gerald Fitzgerald, 11th Earl of Kildare, upon charges of treason.

Christopher St. Lawrence (d. 1589) 7th Baron Howth compiled a book, The Book of Howth, in which he rebutted Henry Sidney’s views of Ireland.

Sidney believed that the medieval conquest of Ireland failed due to the manner in which the descendants of the Norman colonists, the so-called ‘Old English,’ embraced Gaelic customs. He regarded as especially pernicious the system of ‘coign and livery.’ Under ‘coign and livery,’ landowners maintained private armies. Sidney believed this impoverished the country and institutionalised violence. Clavin writes that Lord Howth produced the ‘Book of Howth’ to rebut this interpretation of Irish history and to provide a thinly-veiled critique of Sidney’s reliance on and promotion of English-born officials and military adventurers at the expense of the Old English community. Howth held that the abolition of ‘coign and livery’ would leave the Old English exposed to the depredations of the Gaelic Irish. [5]

Instead of “coign and livery,” the English maintained a royal army, with landowners providing for the soldiers with the “cess.” Christopher St. Lawrence 7th Baron opposed the “cess.” Sidney suggested that a tax be imposed instead of the cess. Lord Howth objected and was imprisoned for six months. He and others similarly imprisoned were released when they acknowledged that the queen was entitled to tax her subjects during times of necessity. [5]

In 1579, Christopher was convicted cruelty towards his wife and children. His wife Elizabeth Plunket was from Beaulieu in County Louth (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/03/17/beaulieu-county-louth/). After he whipped his thirteen year old daughter Jane to punish her, she died. He beat his wife so badly that she had to remain in bed for two weeks, and then fled to her brother. Howth was tried before the court of castle chamber on charges of manslaughter and domestic abuse. Clavin writes that: “In an unprecedented step, given Howth’s social status, the court accepted testimony providing lurid details of his dissolute private life. This may reflect either the crown’s desire to discredit a prominent opposition figure or simply the savagery of his crimes.” [5] He was imprisoned and fined, and made to pay support for his wife and children, from whom he separated, and he fell out of public life.

Amazingly, he later married for a second time, this time to Cecilia Cusack (d. 1638), daughter of an Alderman of Dublin, Henry Cusack. After Christopher died in 1589, she married John Barnewall of Monktown, Co. Meath, and after his death, John Finglas, of Westpalstown, Co. Dublin.

Another legend of the castle stems from around the time of Christopher 7th Baron. When we visited the castle, the dining room was set with a place for a guest. The tradition is to keep a place for any passing guest. This stems from a legend about Grace O’Malley (c.1530-1603), “the pirate queen.”

Grace O’Malley was nicknamed ‘Grainne Mhaol’ (Grace the Bald) because when she was a child she cut her hair when her father Eoghan refused to take her on a voyage to Spain because he believed that a ship was no place for a girl. She cropped her hair to look like a boy. [6]

The story is told that in around 1575, Grace O’Malley landed in Howth on her return from a visit to Queen Elizabeth. However, the Howth website tells us that Grace O’Malley did not visit Queen Elizabeth until 1593. She was in Dublin, however, in 1576, visiting the Lord Deputy. The story tells us that Grace O’Malley proceeded to Howth Castle, expecting to be invited for dinner, and to obtain supplies for her voyage home to Mayo. However, the gates were closed against her. This breached ancient Irish hospitality.

Later, when Lord Howth’s heir was taken to see her ship, she abducted him and brought him back to Mayo. She returned him after extracting a promise from Lord Howth that his gates would never be closed at the dinner hour, and that a place would always be laid for an unexpected guest.

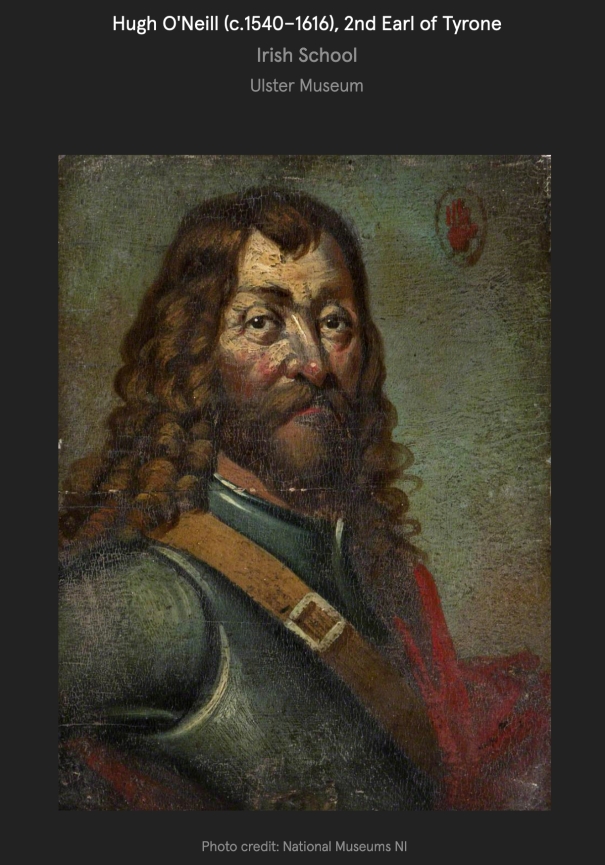

Nicholas the 8th Baron fought with the British against the rebels in the Nine Years War (1594–1603). He fought alongside Henry Bagenal (d. 1598) against Hugh O’Neill (c.1540–1616) 2nd Earl of Tyrone, and accompanied Lord Deputy William Russell, later 1st Baron Russell of Thornhaugh, on his campaign against the O’Byrnes in County Wicklow. In 1601 he went to London to discuss Irish affairs, and the Queen formed a high opinion of him. She was also impressed by Howth’s eldest son Christopher, later 9th Baron Howth. [7]

Nicholas married Margaret, daughter of Christopher Barnewall of Turvey in Dublin. She gave birth to the heir, and her daughter Margaret married Jenico Preston, 5th Viscount Gormanston. When widowed, daughter Margaret married Luke Plunkett, 1st Earl of Fingall.

After his wife Margaret née Barnewall’s death, Nicholas married secondly Mary, daughter of Sir Nicholas White of Leixlip, Master of the Rolls in Ireland, who lived in Leixlip Castle. See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/09/04/leixlip-castle-county-kildare-desmond-guinnesss-jewelbox-of-treasures/.

Nicholas and Margaret’s son Christopher (d. 1619) succeeded as 9th Baron Howth. Christopher 9th Baron also fought against the rebels in the Nine Years War. At some point Christopher converted to Protestantism. He conducted a successful siege at Cahir Castle in County Tipperary against Catholic Butlers. See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/03/29/cahir-castle-county-tipperary-an-office-of-public-works-property/

In 1599, Christopher St. Lawrence 9th Baron was one of six who accompanied Robert Devereux 2nd Earl of Essex on his unauthorised return to England, riding with the earl to the royal palace at Nonesuch, where Essex burst in to Queen Elizabeth’s bedchamber.

Rumour circulated that Christopher St. Lawrence pledged to kill Essex’s arch-rival Sir Robert Cecil. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us:

“In late October he was summoned before the English privy council, where he denied having threatened Cecil’s life. One of the counsellors then referred to his Irishness, the clear implication being that as such he could not be trusted, at which he declared: ‘I am sorry that when I am in England, I should be esteemed an Irish Man, and in Ireland, an English Man; I have spent my blood, engaged and endangered my Liffe, often to doe Her Majestie Service, and doe beseech to have yt soe regarded’ (Collins, Letters and memorials of state, i, 138). His dignified and uncharacteristically tactful response eloquently summed up the quandary of the partially gaelicised descendants of the medieval invaders of Ireland (the Old English), who were regarded with suspicion by the Gaelic Irish and English alike. It also mollified his accusers, who, in any case, recognised that his martial prowess was urgently required in Ireland. Prior to his return to Dublin on 19 January, the queen reversed an earlier decision to cut off his salary, and commended him to the authorities in Dublin.” [8]

Christopher married Elizabeth Wentworth, daughter of Sir John Wentworth of Little Horkesley and Gosfield Hall, Essex, but by 1605 they separated, and the Privy Council ruled that he must pay for her maintenance. The St. Lawrence family inherited estates near Colchester from her family.

By 1601, while fighting in Ulster alongside the Lord Deputy Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, many of the men Christopher commanded were Gaelic Irish. Increasingly dissatisfied, Christopher St. Lawrence began to alienate leading members of the political establishment.

In 1605 the government began prosecuting prominent Catholics for failing to attend Church of Ireland services. Although Protestant, St. Lawrence’s family connections led him to identify with the Catholic opposition. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that he became involved in the planning of an uprising in late 1605, along with Hugh O’Neill, despite his father having previously battled against O’Neill. [8]

Low on funds, and not having yet inherited Howth, he sought to join the Spanish army in Flanders, where an Irish regiment had been established in 1605. He wanted support for a rebellion against the British crown. However, perhaps realising that an uprising would fail, he turned into an informant for the government. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that he sought to consolidate ties to the establishment by arranging the marriage of his son and heir Nicholas to a daughter of the Church of Ireland bishop of Meath, George Montgomery, in 1615.

Christopher acted as a secret agent for the Crown, while pretending to be part of the rebellion against the Crown. He was afraid of being discovered as a traitor. The Dictionary of Biography has a long entry about his and his double dealings. He died in 1619 at Howth and was buried at Howth abbey on 30 January 1620. He and his wife had two sons and a daughter; he was succeeded by his eldest son, Nicholas. [8]

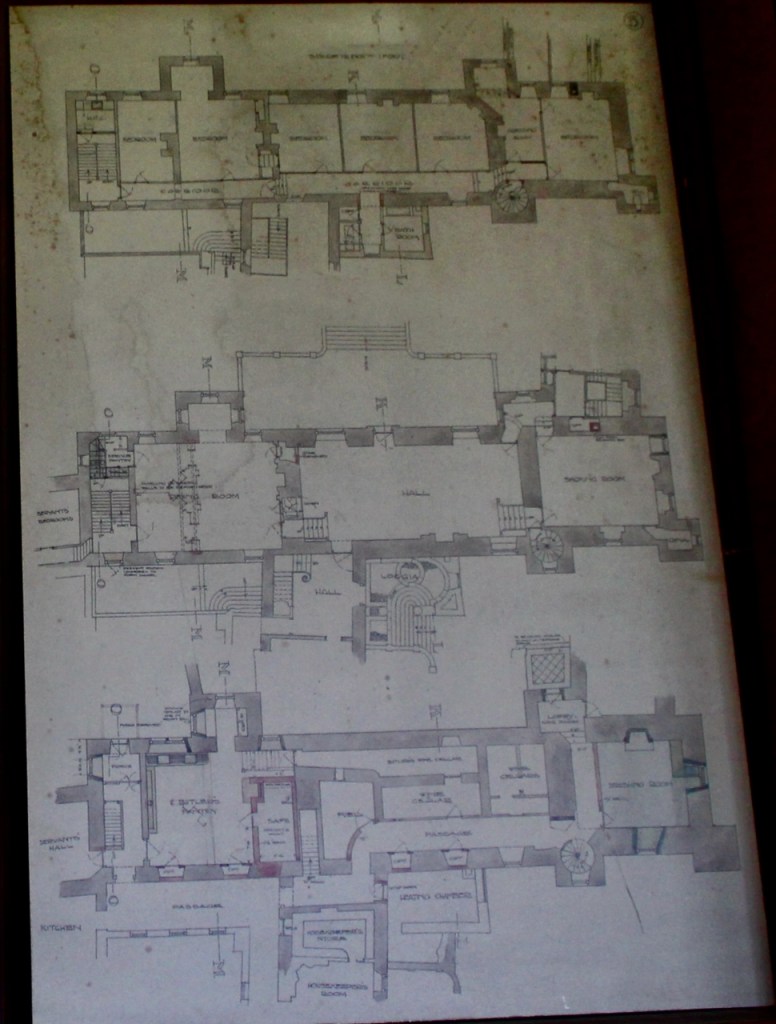

Nicholas St. Lawrence (d. 1643/44) 10th Baron Howth added the top floor above the hall of Howth Castle sometime prior to 1641. He and his wife Jane née Montgomery had two daughters: Alison, who married Thomas Luttrell of Luttrellstown Castle (now a wedding venue), and Elizabeth.

Nicholas’s brother Thomas (d. 1649) succeeded as 11th Baron. Thomas’s son, William St. Lawrence (1628-1671), succeeded as 12th Baron Howth. The 12th Baron was appointed Custos Rotulorum for Dublin in 1661, and sat in the Irish House of Lords.

Nicholas the 10th Baron’s daughter Elizabeth married, as her second husband, her cousin William St. Lawrence 12th Baron Howth. She gave birth to the 13th Baron Howth.

Thomas St. Lawrence (1659-1727) 13th Baron Howth inherited the title when he was only twelve years old. Thomas Butler, 6th Earl of Ossory was appointed by his father as his legal guardian.

Thomas St. Lawrence married Mary, daughter of Henry Barnewall, 2nd Viscount Barnewall of Kingsland, County Dublin. After first backing King James II, in 1697 he signed the declaration in favour of King William III.

His son William (1688-1748) succeeded as 14th Baron, and carried out extensive work on Howth Castle, completing the project in 1738. A painting dating from this period commemorates the work.

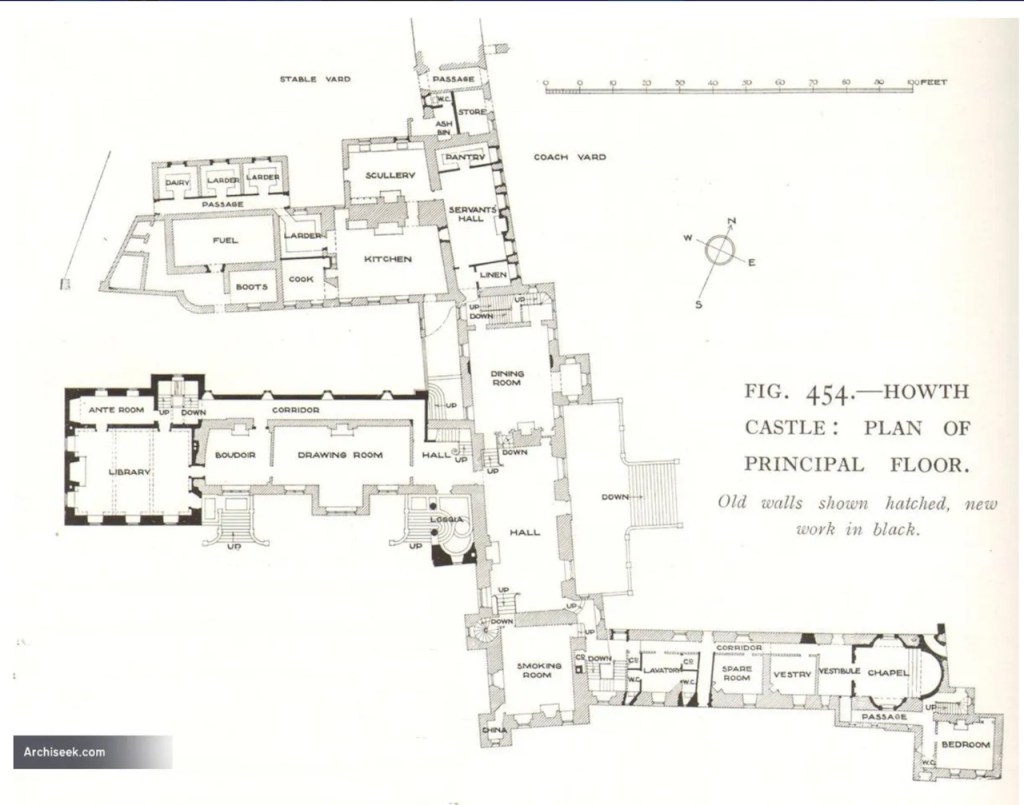

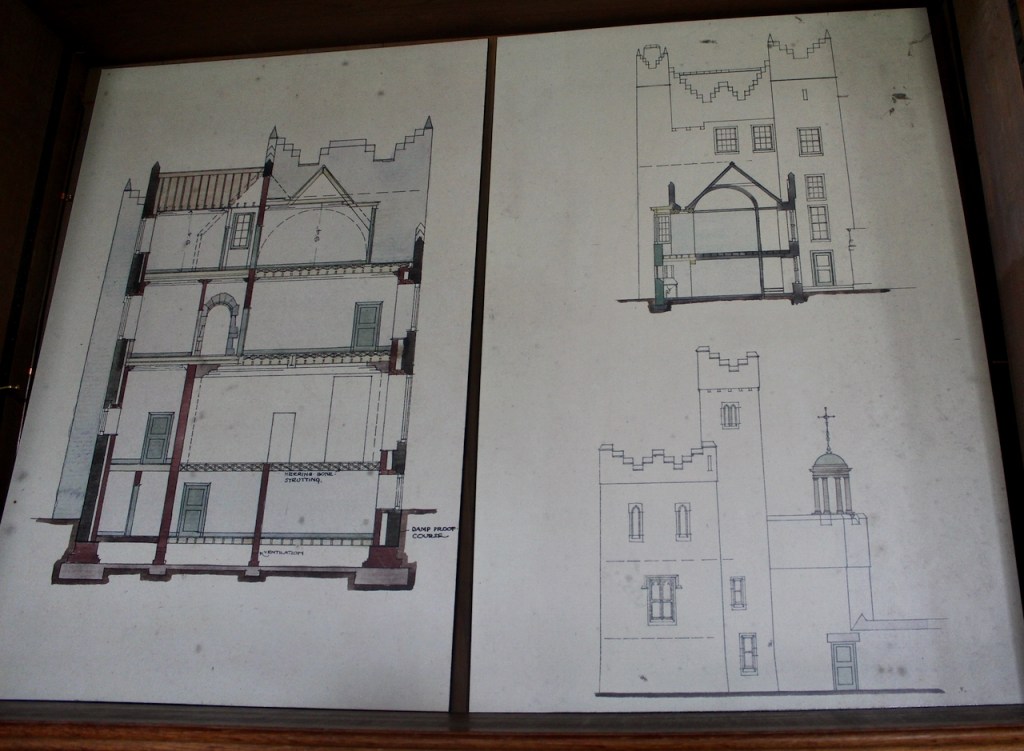

Mark Bence-Jones writes that the castle is “Basically a massive medieval keep, with corner towers crenellated in the Irish crow-step fashion, to which additions have been made through the centuries. The keep is joined by a hall range to a tower with similar turrets which probably dates from early C16; in front of this tower stands a C15 gatehouse tower, joined to it by a battlemented wall which forms one side of the entrance court.” [see 1]

Mark Bence-Jones describes the central part of the front of the house:

“The hall range, in the centre, now has Georgian sash windows and in front of it runs a handsome balustraded terrace with a broad flight of steps leading up to the entrance door, which has a pedimented and rusticated Doric doorcase. These Classical features date from 1738, when the castle was enlarged and modernized by William St. Lawrence, 14th Lord Howth, who frequently entertained his friend Dean Swift here.” [see 1]

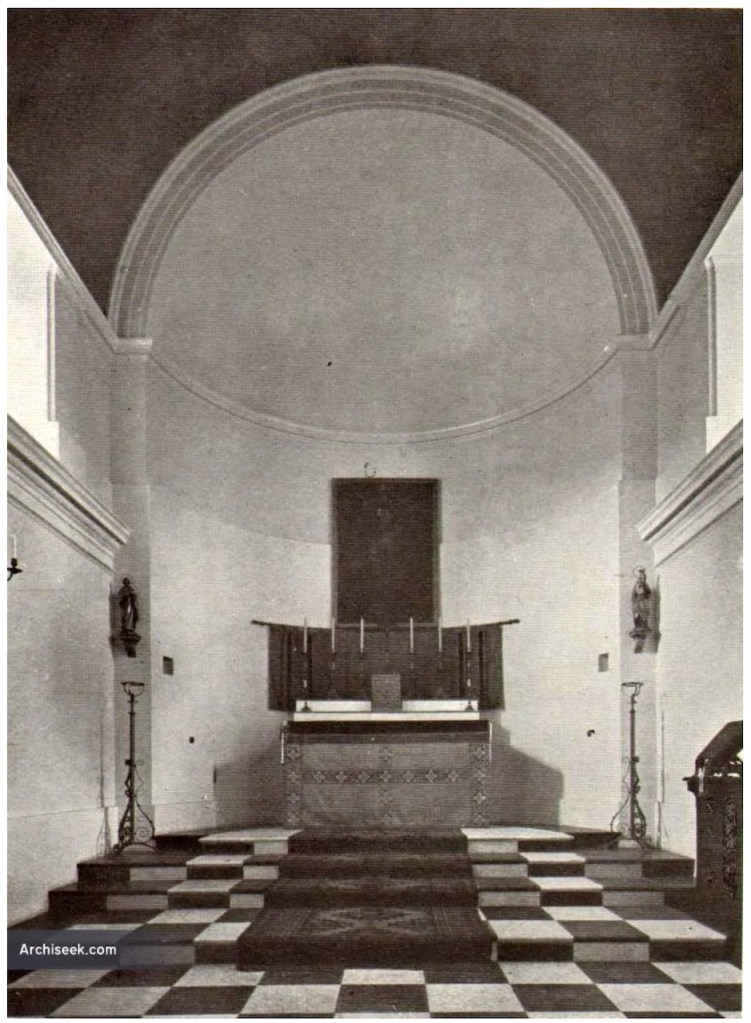

Mark Bence-Jones describes: “The hall has eighteenth century doorcases with shouldered architraves, an early nineteenth century Gothic frieze and a medieval stone fireplace with a surround by Lutyens.” [see 1] The hall was added to the medieval tower in 1558 by Christopher, who is the 20th Lord of Howth according to the Howth Castle website, or the 7th Baron. It was later adapted by Edwin Lutyens in around 1911.

In Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life, Sean O’Reilly writes about the article written about Howth Castle by Weaver for Country Life:

“It is Lutyens’s selective retention and sensitive recovery of surviving original fabric from a variety of eras that distinguishes his work at Howth. The entrance hall, at the head of a wide flight of stairs, displays best his ability to empathise. While the photographs, by an unknown photographer and by Henson, convey his success, Weaver’s summary clarifies the architect’s methodology: ‘The general work of reparation in the interior revealed in the hall fireplace an old elliptical arch which enabled the original open hearth to be used once more. Above it Mr Macdonald Gill had painted, under Mr Lutyens’ direction, a charming conventional map of Howth and the neighbouring sea and a dial which records the movement of a wind gauge.’ ” [11]

The chimneypiece in the entrance hall was developed from existing Georgian and Victorian features, Seán O’Reilly tells us, with medieval fabric recovered during renovation, providing a mix of styles typical of Lutyens’ restorations. I wish I could find my notes to tell you more about the map painted by MacDonald Gill! I will just have to return so historian Daniel can tell me again.

We were lucky enough to visit the castle when it hosted an exhibition of paintings by Peter Pearson, which feature in a book: Of Sea and Stone: Paintings 1974-2014.

William the 14th Baron (1688-1748) married Lucy, younger daughter of Lieutenant-General Richard Gorges of Kilbrew, County Meath. Her mother was Nicola Sophia Hamilton, who before marrying Richard Gorges, had been married to Tristram Beresford, 3rd Baronet of Coleraine.

The Howth Castle website reminds us of a story that our guide on our visit to Curraghmore in County Waterford told us:

“For many years in the Drawing Room of the castle hung the portrait of a handsome woman. To the back of the portrait was attached an unsigned and undated note stating that the painting once had a black ribbon round the wrist but that this had been removed during cleaning. The woman is Nicola Hamilton born 1667 who married firstly Sir Tristram Beresford and subsequently General Richard Gorges. The younger daughter of this marriage was Lucy Gorges, wife of the 27th Lord Howth, Swift’s ‘blue-eyed nymph’.”

“The legend is that when she was quite young, she made an agreement with John Le Poer, Earl of Tyrone that whoever died first would come back and appear to the other. On dying Lord Tyrone came to her in the night, assured her of the truth of the Christian Revelation and made various predictions, that her first husband would soon die, that her son would marry the Tyrone heiress, and that she herself would die in her forty-seventh year, all of which came true. To convince her of the reality of his presence, he grasped her wrist causing her an injury and permanent scar which she concealed beneath a black ribbon.

“The ease with which the ribbon was removed from the portrait does little to enhance the veracity of the story.“

Nicola’s son was Marcus Beresford (1694-1763) 4th Baronet of Coleraine and as the ghost predicted, he married Catherine Le Poer of Curraghmore, daughter and heiress of James, 3rd Earl of Tyrone.

William St. Lawrence 14th Baron of Howth spent much time at another house he owned in Ireland, Kilfane in County Kilkenny. [12] He sat in the Irish House of Commons as MP for Ratoath between 1716 and 1727, and became a member of the Privy Council of Ireland in 1739.

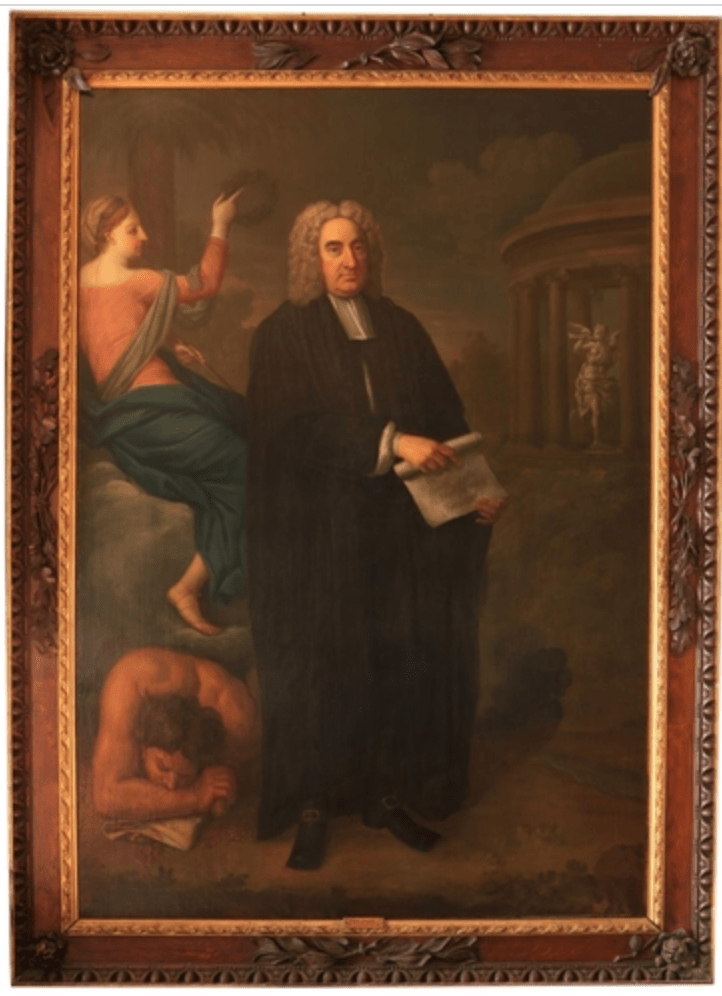

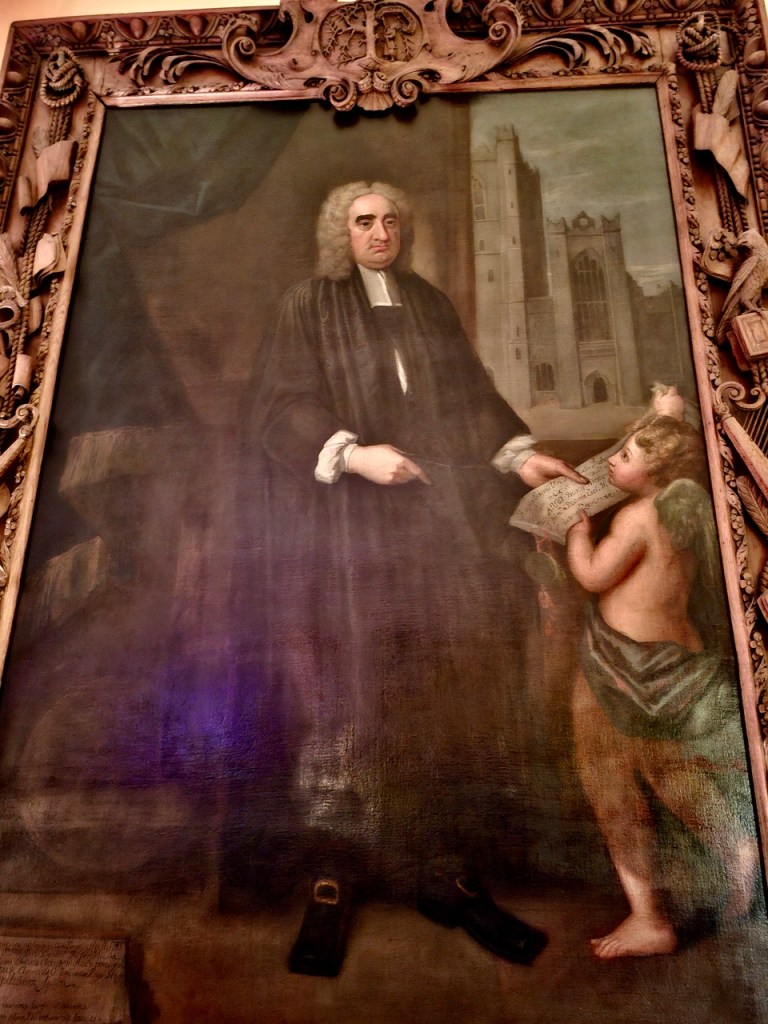

William 14th Baron came to know Jonathan Swift through his wife. Swift became a regular visitor to Howth Castle and they exchanged numerous letters. At Howth’s request, Swift had his portrait painted by Francis Bindon.

The painting of Jonathan Swift by Francis Bindon was offered at auction in 2021. A very similar painting by Bindon is owned by the Deanery of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. An obituary notice about Bindon in Faulkner’s Journal from 1765 describes Bindon as “one of the best painters and architects this nation has ever produced” and a copy of the Swift picture, painted by Robert Home, hangs in the Examination Hall at Trinity College, Dublin.

In 1736, Lady Lucy Howth’s brother Hamilton Gorges killed Lord Howth’s brother Henry St. Lawrence in a duel. Gorges was tried for murder but acquitted.

After her husband died, Lucy married Nicholas Weldon of Gravelmount House in County Meath, a Section 482 property which we visited. (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/06/13/gravelmount-house-castletown-kilpatrick-navan-co-meath/ )

William 14th Baron and Lucy’s son Thomas (1730-1801) succeeded as 15th Baron. He was educated in Trinity College Dublin, and succeeded to the title when he was eighteen years old, after his father’s death. He became a barrister, and was elected as a “Bencher,” or Master of the Bench of King’s Inn in Dublin in 1767.

In 1750 he married Isabella, daughter of Henry King, 3rd Baronet of Boyle Abbey in County Roscommon.

In 1767 Thomas was created Viscount St. Lawrence and then Earl of Howth. He was appointed to Ireland’s Privy Council in 1768. Timothy William Ferres tells us that in consideration of his own and his ancestors’ services, he obtained, in 1776, a pension of £500 a year.

His daughter Elizabeth married Dudley Alexander Sydney Cosby, 1st and last Baron Sydney and Stradbally, whom we came across when we visited Stradbally Hall in County Laois (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/10/14/stradbally-hall-stradbally-co-laois/ ). A younger son, Thomas St. Lawrence (1755-1831), became Lord Bishop of Cork and Ross. He’s the one who supposedly heard the mermaid in the tower!

Thomas’s son William (1752-1822) succeeded as 2nd Earl. William married firstly, in 1777, Mary Bermingham, 2nd daughter and co-heiress of Thomas, 1st Earl of Louth. Mary gave birth to several daughters.

A daughter of the 2nd Earl of Howth, Isabella (d. 1837), married William Richard Annesley, 3rd Earl Annesley of Castlewellan, County Down.

Mary née Bermingham died in 1773 and William 2nd Earl of Howth then married Margaret Burke, daughter of William Burke of Glinsk, County Galway.

Howth Harbour was constructed from 1807, and in 1821, King George IV visited Ireland, landing at Howth pier.

Margaret the second wife, Countess of Howth, gave birth to a daughter Catherine, who married Charles Boyle, Viscount Dungarvan, son of the 8th Earl of Cork. She also gave birth to the heir, Thomas (1803-1874), who succeeded as 3rd Earl of Howth in 1822.

Thomas the 3rd Earl served as Vice-Admiral of the Province of Leinster, and Lord-Lieutenant of County Dublin. He married Emily, daughter of John Thomas de Burgh, the 1st Marquess of Clanricarde.

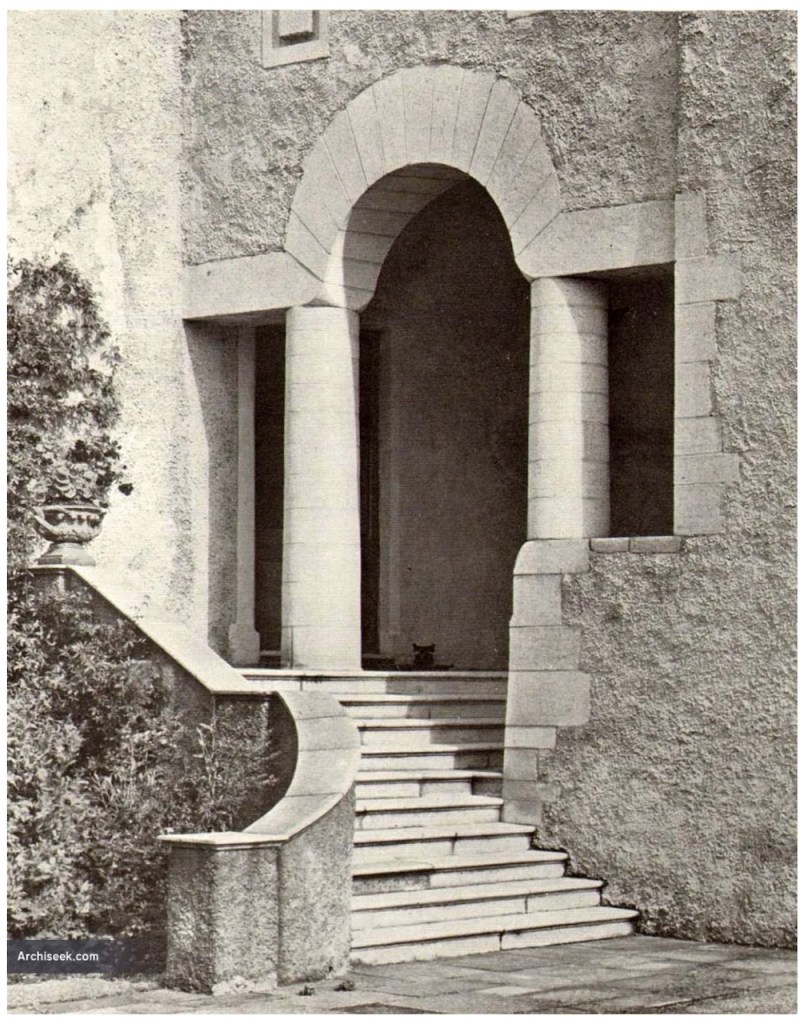

Around 1840, Richard Morrison drew up plans for alterations in the castle, which were only partially executed, including Gothicizing the stables. [see 2]

Emily gave birth to several children, including the heir, but died of measles at the age of thirty-five, in 1842.

Emily and Thomas had a daughter, Emily (d. 1868), who married Thomas Gaisford (d. 1898). Another daughter, Margaret Frances, married Charles Compton William Domvile, 2nd Baronet of Templeogue and Santry.

The 3rd Earl married for a second time in 1851, to Henriette Elizabeth Digby Barfoot. She had a daughter, Henrietta Eliza, who married Benjamin Lee Guinness (1842-1900), and two other children.

In 1855 the 3rd Earl had the Kenelm Lee Guinness Tower built at the end of the east range at the front of the castle. Kenelm was the son of Henrietta née St. Lawrence and Benjamin Lee Guinness. The tower must have been named later, as Kenelm was born in 1887.

Thomas and Emily’s son William Ulick Tristram (1827-1909) succeeded as 4th Earl in 1874. He served as Captain in the 7th Hussars 1847-50. He was High Sheriff of County Dublin in 1854 and State Steward to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1855 until 1866. In the English House of Commons he served as Liberal MP for Galway Borough from 1868 until 1874.

He had no children and the titles died with him.

The property passed to his sister Emily’s family, and her son added St. Lawrence to his surname to become Julian Charles Gaisford-St. Lawrence (d. 1932). In 1911 he hired Edwin Lutyens to renovate and enlarge the castle.

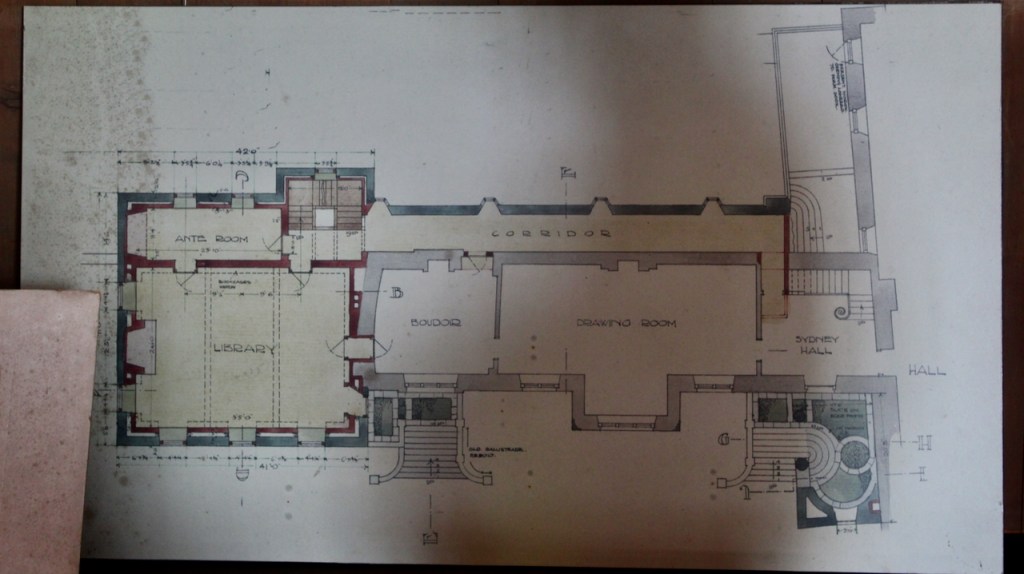

The most substantial addition was the three bay two storey Gaisford Tower, with basement and dormer attic, at the end of the west wing, which he built to house his library. This tower picked up many of the motifs distinguishing the earlier fabric, from its irregular massing to the use of stepped battlements with pyramidal pinnacles, all moulding it into the meandering fabric of the earlier buildings. [see 11] Other work included the steps to the east of the new tower, a loggia with bathrooms above between the old hall and the west wing and a sunken garden. He also added square plan corner turrets to the south-west and north-east facades, incorporating fabric of earlier structures, 1738 and ca 1840. [see 2]

Mark Bence-Jones writes:

“On the other side of the hall range, a long two storey wing containing the drawing room extends at right angles to it, ending in another tower similar to the keep, with Irish battlemented corner turrets. This last tower was added 1910 for Cmdr Julian Gaisford-St. Lawrence, who inherited Howth from his maternal uncle, 4th and last Earl of Howth, and assumed the additional surname of St Lawrence; it was designed by Sir Edward Lutyens, who also added a corridor with corbelled oriels at the back of the drawing room wing and a loggia at the junction of the wing with the hall range; as well as carrying out some alterations to the interior.”

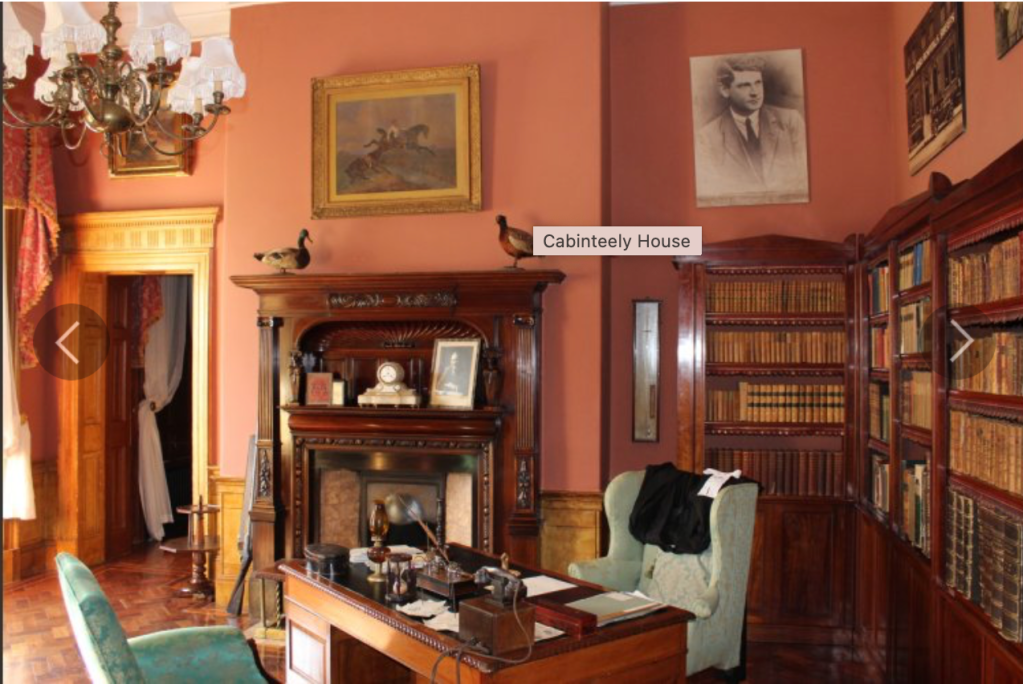

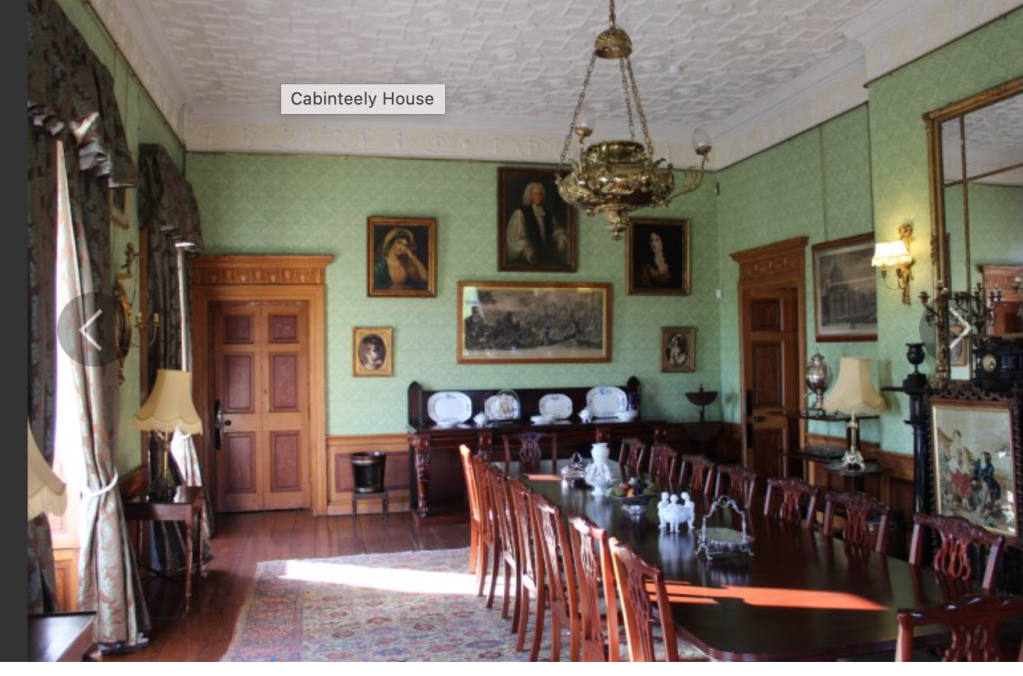

From the front hall, to the right, when facing the fireplace, is the dining room. It has surviving eighteeth century panelling.

Bence-Jones writes that Lutyens restored the dining room to its original size after it had been partitioned off into several smaller rooms. It has a modillion cornice and eighteenth century style panelling with fluted Corinthian pilasters.

The drawing room was left largely untouched by Lutyens.

Mark Bence-Jones writes: “The drawing room has a heavily moulded mid-C18 ceiling, probably copied from William Kent’s Works of Inigo Jones; the walls are divided into panels with arched mouldings, a treatment which is repeated in one of the bedrooms.”

Before entering the library we entered another room, the Boudoir, which contains an old map of the estate. At its height, the Howth Estate covered about 15,000 acres. This estate stretched from Howth to Killester and partially through North County Dublin and Meath.

This room also has a beautiful decorative ceiling.

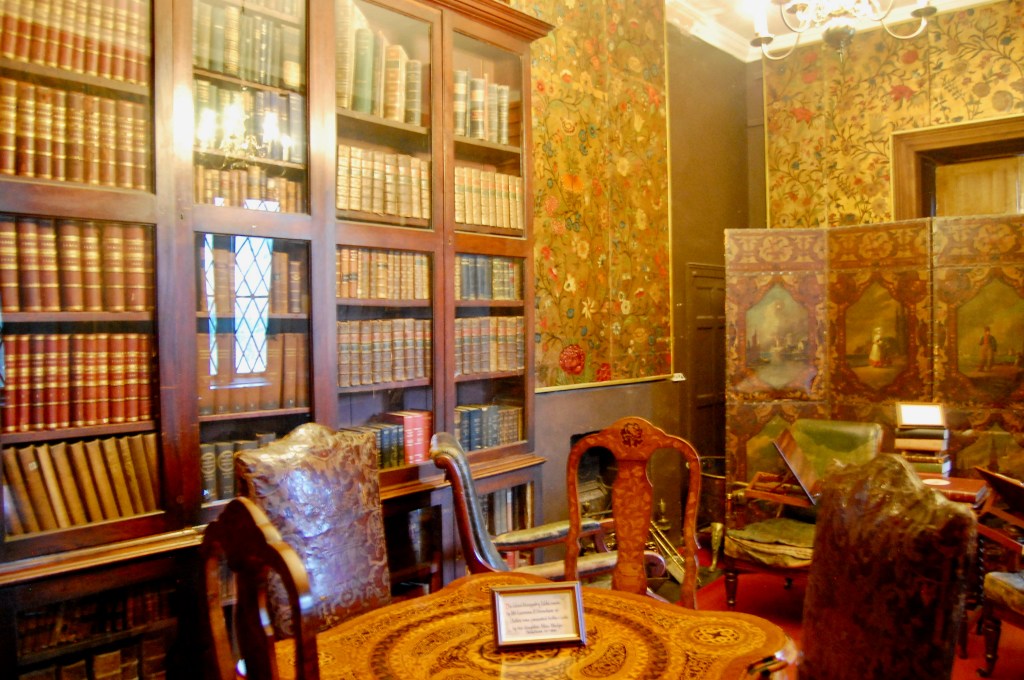

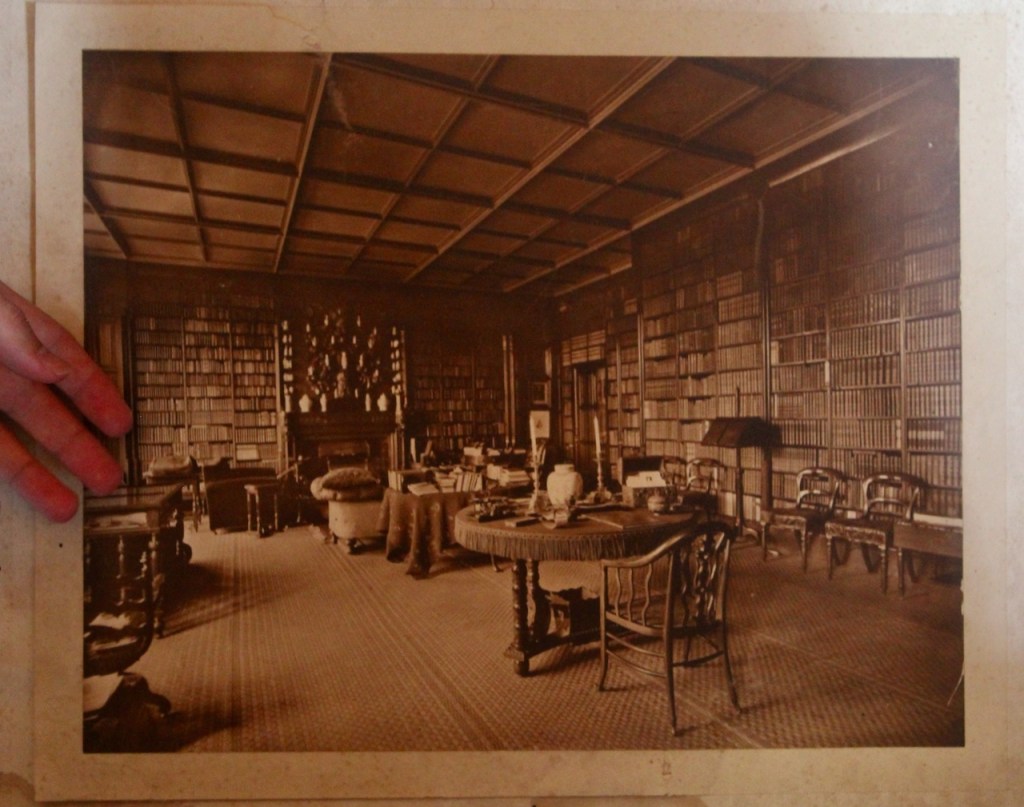

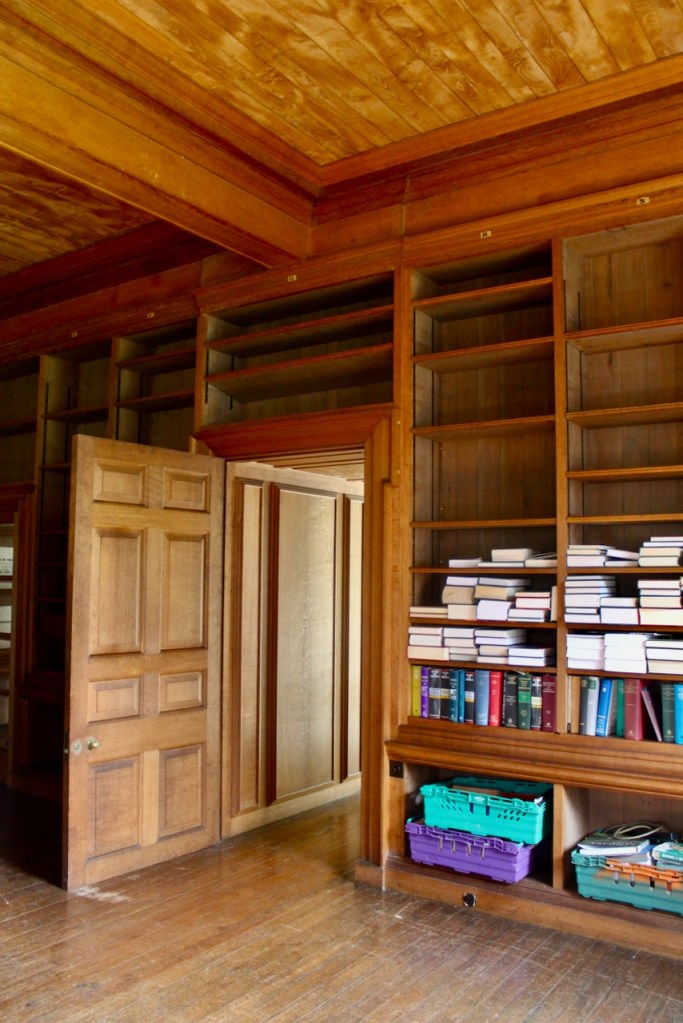

The library, by Lutyens, in his tower, has bookcases and panelling of oak and a ceiling of elm boarding.

Lutyens added a long corridor to one side of the drawing room and boudoir.

We also passed the staircase, but the tour did not include upstairs.

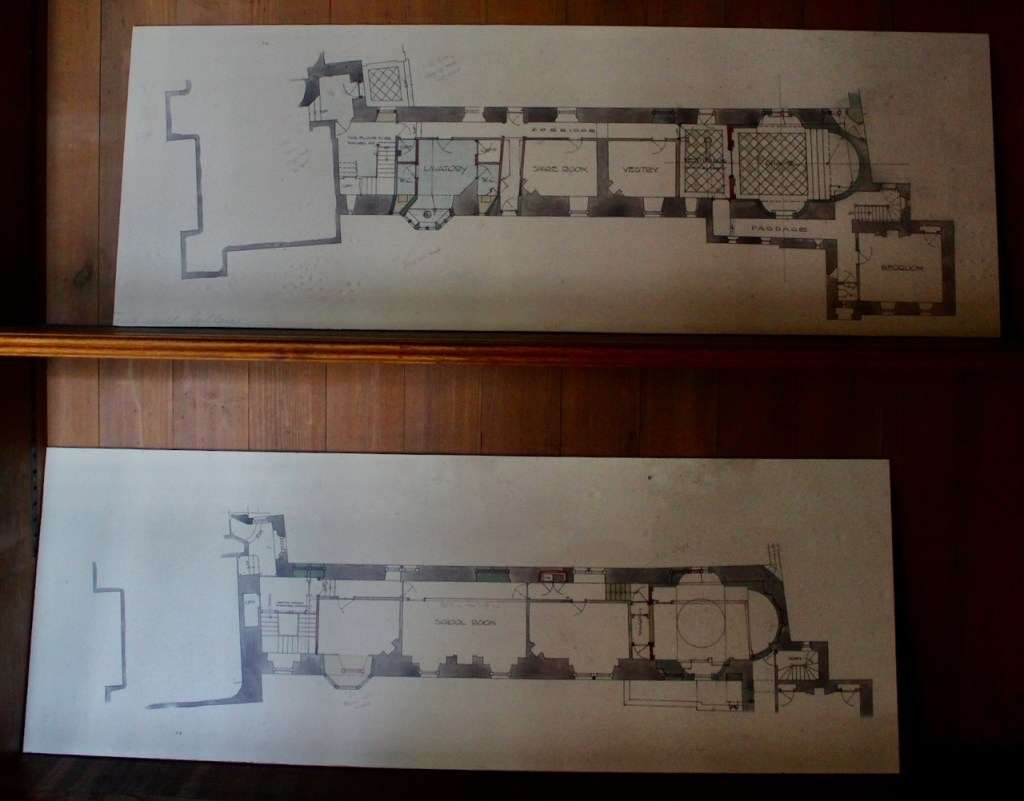

Mark Bence-Jones tells us: “Lutyens also made a simple and dignified Catholic chapel in early C19 range on one side of the entrance court; it has a barrel-vaulted ceiling and an apse behind the altar.”

The addition to the east wing by Lutyens in around 1911 contains the chapel. Unfortunately we did not get to see inside this wing.

Bence-Jones also tells us that the castle has famous gardens, with a formal garden laid out around 1720, gigantic beech hedges, an early eighteenth century canal, and plantings of rhododendrons. I will have to return to see the gardens!

We walked around the side, around what I think is the stable block, past the Mermaid Tower.

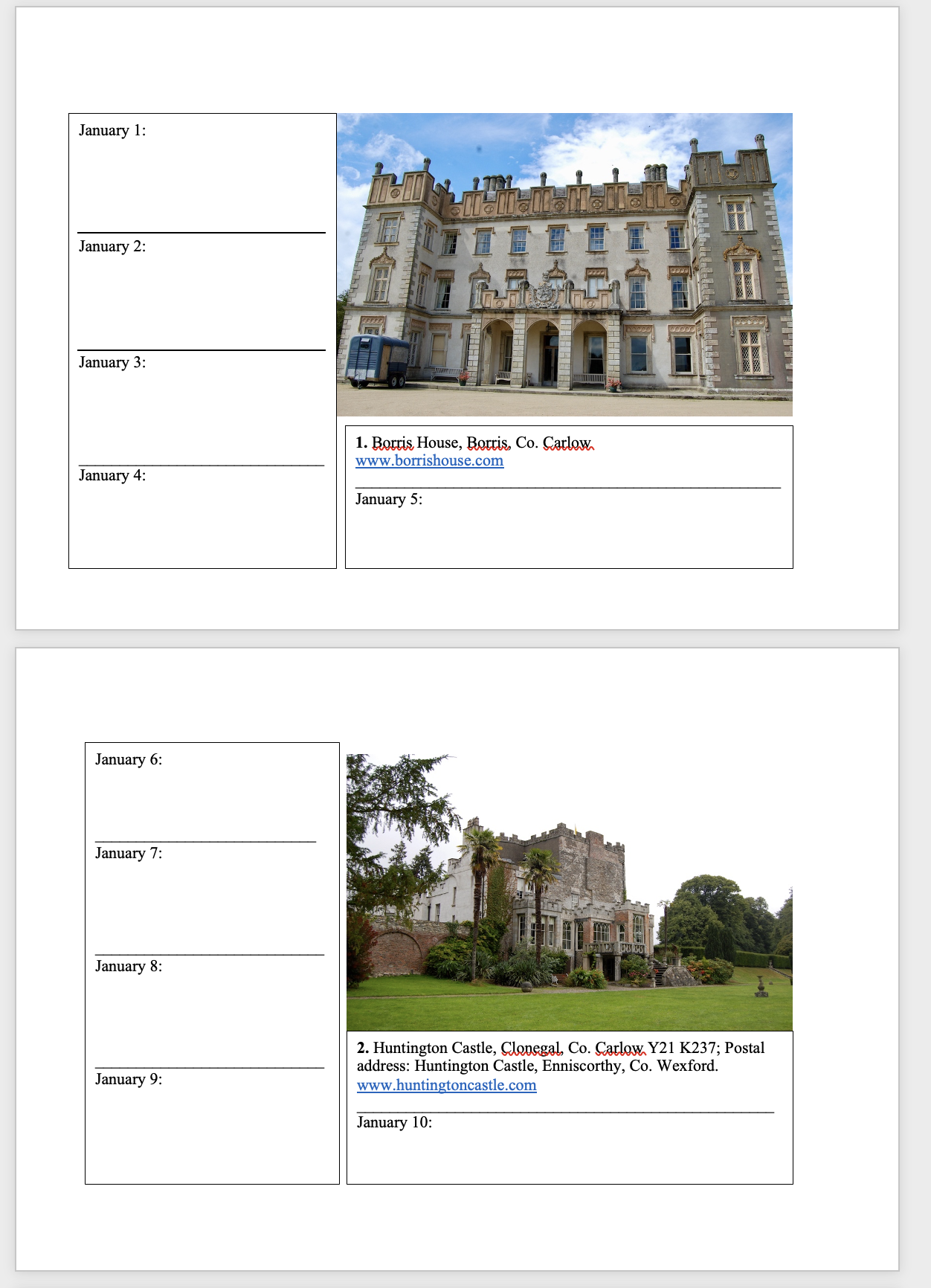

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Donation towards website.

I receive no funding nor aid to create and maintain this website, it is a labour of love. The website costs €300 annually on wordpress. Help to fund the website.

€150.00

[1] p. 155. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[2] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2013/07/howth-castle.html

[4] https://www.dib.ie/index.php/biography/st-lawrence-sir-nicholas-a8221

[5] https://www.dib.ie/index.php/biography/st-lawrence-christopher-a8219

[6] https://www.dib.ie/biography/omalley-grainne-grace-granuaile-a6886

[7] Ball, F. Elrington History of Dublin 6 Volumes Alexander Thoms and Co. Dublin 1902–1920.

[8] https://www.dib.ie/index.php/biography/st-lawrence-sir-christopher-a8220

[9] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/medp://tia/100792

[10] Dublin City Library and Archives. https://repository.dri.ie

[11] p. 38. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Sean O’Reilly. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

[12] Ball, F. Elrington History of Dublin Vol. 5 “Howth and its Owners” University Press Dublin 1917 pp. 135-40

[13] www.archiseek.com