Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is my “full time job” and created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My costs include travelling to our destinations from Dublin, accommodation if we need to stay somewhere nearby, and entrance fees. Your donation could also help with the cost of the occasional book I buy for research (though I mostly use the library – thank you Kevin Street library!). Your donation could also help with my Irish Georgian Society membership or attendance for talks and lectures, or the Historic Houses of Ireland annual conference in Maynooth.

€15.00

We visited the Castle of Castletownshend when on holidays in County Cork in June 2022. The Castle is a hidden gem, full of history. We definitely look forward to a return visit, to stay in the Castle, which provides B&B accommodation.

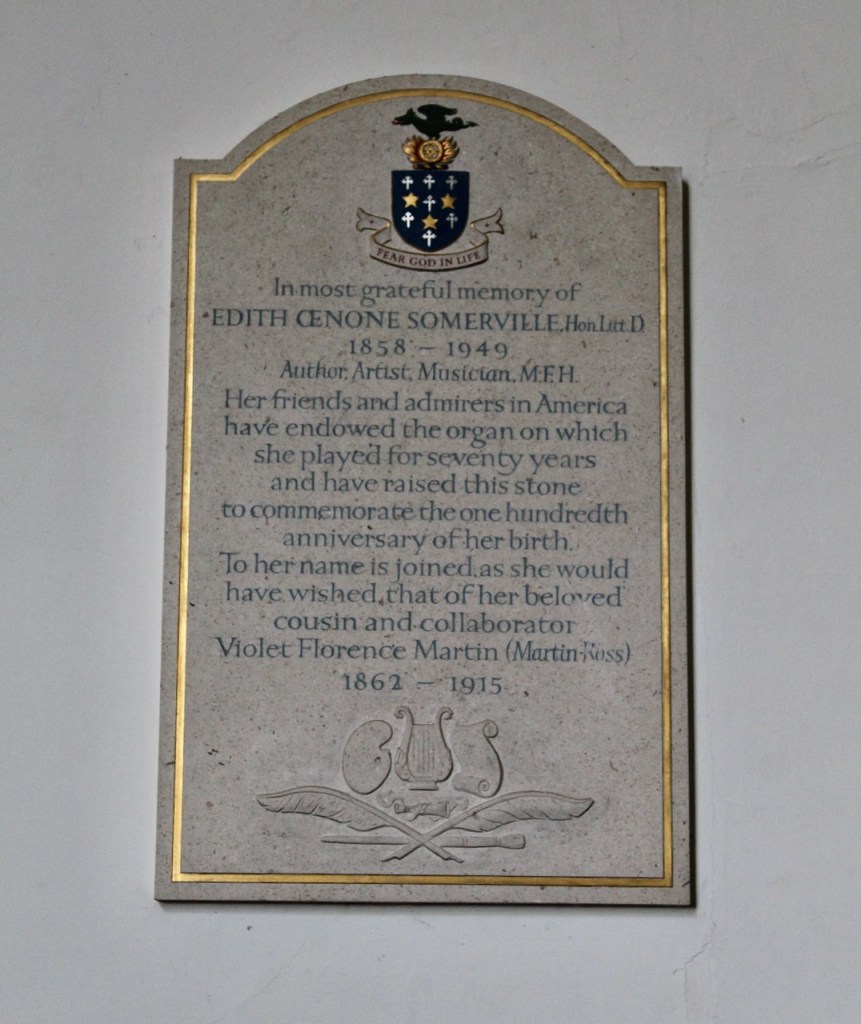

The castle remains in the ownership of the same family, the Townshends, who built it and who have lived here since the 1650s! We came upon the Townshend family of Castletownshed when we visited Drishane House. The Somervilles of Drishane intermarried with their cousins the Townshends who lived down the road. See my write-up:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/03/07/drishane-house-castletownshend-co-cork/

The website tells us:

“In the picturesque village of Castletownshend, past ‘The Two Trees’ at the bottom of the hill, you’ll find our family-run boutique B&B. Nestled at the edge of a scenic harbour and natural woodlands for you to explore, The Castle is a truly unique place to stay. It has the warm, homely feel of a traditional Irish B&B, but with a few extra special touches.“

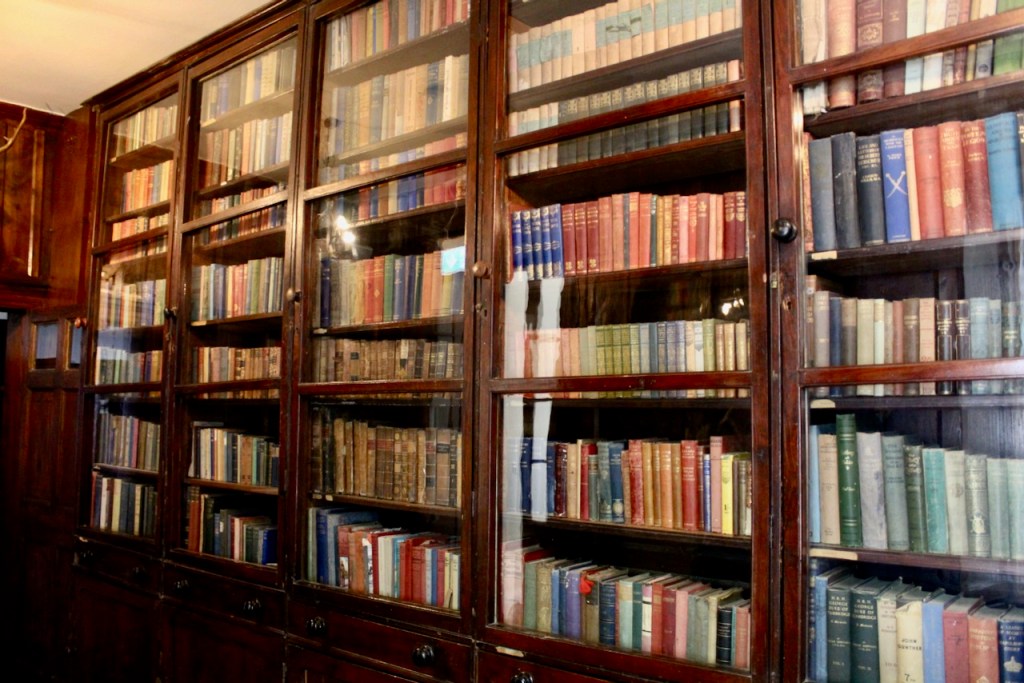

The website continues: “Steeped in history, The Castle has been home to the Townshend family since the 1650s and has been receiving guests for over 60 years. Inside the old stone walls, you’ll find welcoming faces to greet you, roaring fires to warm you, and comfy beds to sink into. Each room has its own story to tell, with the oak-panelled hall and spacious dining room retaining most of their original features, furniture, and family portraits.“

The website explains the family name: “The family name has undergone several changes over the years. The original spelling was Townesend, which later became Townsend. In 1870, the head of the family, Reverend Maurice Fitzgerald Townshend [1791-1872], consulted with the Townshends of Raynham, Norfolk. Following this, it was requested that the whole family add the ‘h’ into the name. However, some families were quite content with the current spelling and refused to adopt the new one. This resulted in various different spellings spread across the branches throughout the UK, Ireland, Australia and Canada.” [1]

The centre of the castle is the oldest part, and the two end towers are later additions.

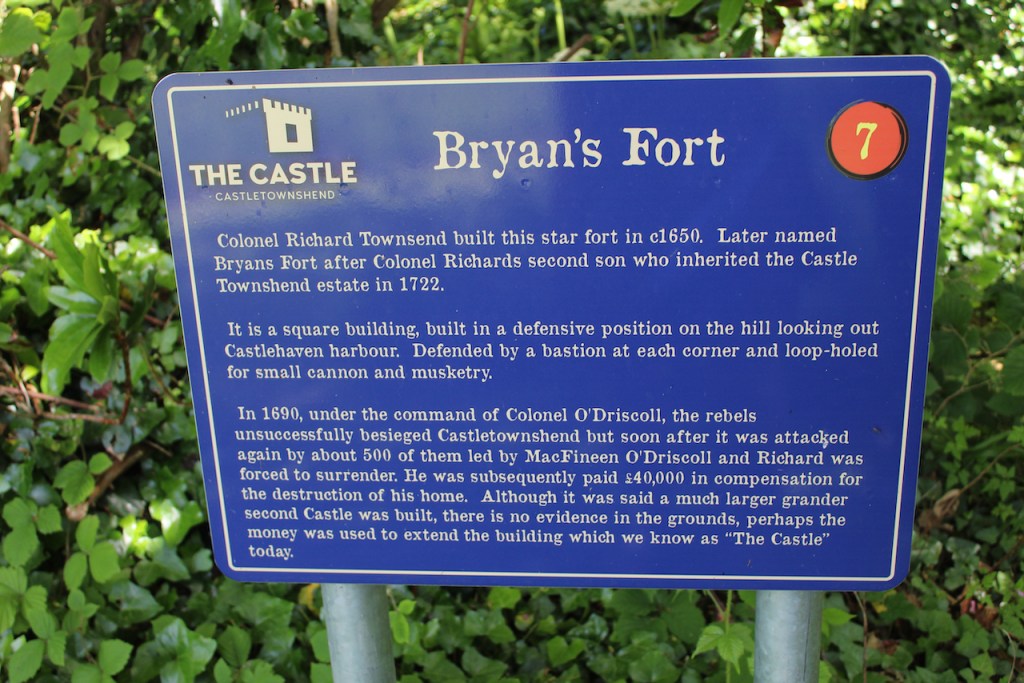

The website tells us: “The building is in fact a 17th century castellated house, not a defensive castle from earlier times. It was built by Colonel Richard Townesend [1618-1692] towards the end of the 17th century, starting off as a much smaller dwelling. The first castle, known as ‘Bryan’s Fort’ [named after his son Bryan (1648-1726)], was attacked and destroyed by the O’Driscolls in 1690, and its ruins remain in The Castle grounds to this day. Richard then built a second castle, which is thought to be where Swift’s Tower still stands.“

The website continues “In 1805 the floors were lowered to make the ceilings higher, a decision that left The Castle in ruins. However, instead of rebuilding it, the stone was used to add castellated wings to the dwelling on the waterfront. This became The Castle as you see it today.“

The inside is a real treat, with wonderful family portraits in the hall of oak and what looks like leather wall covering.

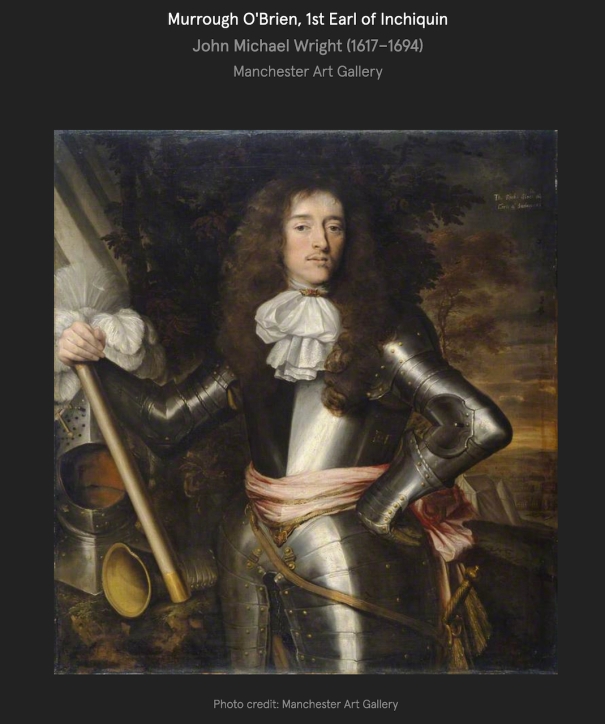

Colonel Richard Townesend (1618-1692), who was born in England, gained the rank of Officer in the Parliamentary Army in the British Civil War. [2] The Parliament objected to the monarchy of the Stuarts, and they charged the king, Charles I, of treason against the state and ultimately beheaded him. Oliver Cromwell brought troops to Ireland to subdue those loyal to the monarchy. The opposing force to the royalist forces was called the Parliamentary army. Townesend fought in the Battle of Knocknanauss, County Cork in April 1648, where he commanded the main body of the Army under Murrough O’Brien (1614-1674) 1st Earl of Inchiquin. They fought the Irish Confederates, who supported King Charles I in the belief that in reward for their loyalty he would grant them greater self-governance. The Confederate forces were made up of Irish Catholics and “old English” Anglo-Normans who sought to protect their land holding and to end anti-Catholic legislation. The Parliamentarians overcame the Confederates in the battle, and around 3,000 Confederates died at Knocknanauss and up to 1,000 English Parliamentarians.

Richard Townesend’s loyalty to the Parliamentarians wavered after this battle and after the death of Charles I. He returned to Ireland, and he was arrested for being involved in a plot to overcome Lord Inchiquin. However, he may have been a “plant” to undermine the opposition. A mutiny in the garrison at Cork however led to his freedom and Cromwell praised him for being an “instrument in the return of Cork and Youghal to their obedience.” He retired from the military and settled in Castletownshend before 1654. [3]

He managed to hold on to his land after the Stuart monarchy was restored to Charles II. The Dictionary of National Biography suggests that this could be due connections between his wife Hildegardis Hyde and the Lord Chancellor of England, Edward Hyde 1st Earl of Clarendon. Richard held the office of Member of Parliament in the Irish Parliament for Baltimore, County Cork in 1661. He held the office of High Sheriff of County Cork in 1671.

In 1690, after the accession of King James II to the throne, Richard’s home in Castetownshend was unsuccessfully beseiged by 500 Irishmen led by the O’Driscolls, a family who had owned the land before Townesend [for more on the O’Driscolls, see my entry on Baltimore Castle, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/12/28/dun-na-sead-castle-baltimore-co-cork-981-x968/ ]Townesend died in 1692, leaving seven sons and four daughters. [see 3]

Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe tells us of the Castle’s builder, in her Voices from the Great Houses: Cork and Kerry (Mercier Press, Cork, 2013): p. 83. “In the late 1600s Richard Townsend, an officer in the Cromwellian army, acquired lands at Castlehaven in west Cork originally owned by the O’Driscoll clan. Richard Townsend also owned other lands in County Cork totalling over 6,540 acres. It was he who built the castle at Castletownshend, the centre portion of which still remains. The two towers at each corner of the castle today were added in the eighteenth century.” [4]

Although she identifies the centre of the castle to be built by Richard in the 1600s, Frank Keohane describes Castle Townshend in his Buildings of Ireland: Cork City and County and suggests that this part was built in 1780. The castle Richard built is probably the ruin nearby. In fact, An Officer of the Long Parliament (1892) we are told that he lived for some time in Kilbrittan Castle nearby, “a splendid very pile overlooking Courtmacsherry Bay, which had been forfeited by the head of the McCarthies for his participation in the Rebellion of 1641.“

Richard Townesend’s early house at Castletownshend is described in An Officer of the Long Parliament (1892):

p. 107-08. “It seems to have consisted of a dwelling – house and small courtyard all comprised in a square enclosure with a bastion at each angle, pierced with loopholes for musketry and some embrasures for small cannon. It was built on a well- chosen site of some strength. The dwelling-house consisted of two stories, the upper one overlooking the harbour. The lower one must have been lighted from the court, on the outer side of which was a parapet for defending the wall. It seems to have been hastily built, as the stones are small and not well put together….A larger mansion appears to have been built before long, which was valued at £ 40,000 , when destroyed in the troubles of 1690.”

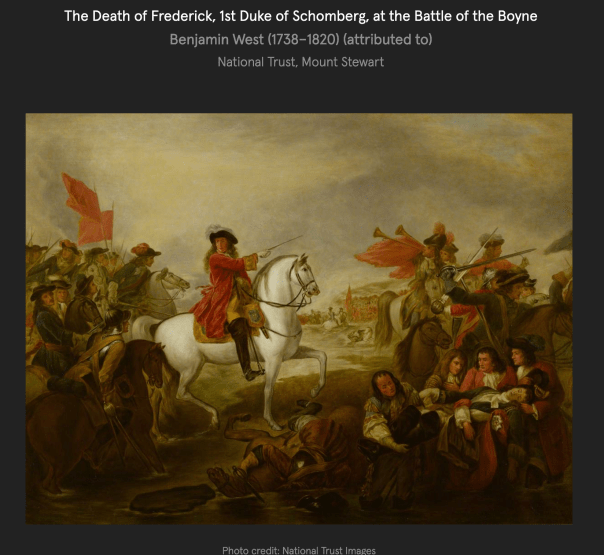

Richard Townesend’s son Horatio was in the navy and in 1690 carried the Duke of Schomberg, who fought in King William’s army, to Ireland on board his sloop. He married Elizabeth, daughter of the MP for Baltimore, Thomas Becher.

Another son, John, married Catherine Barry, daughter of Richard, 2nd Earl of Barrymore. Son Philip (1664-1735), became a Protestant clergyman and married Helen Galwey of Lota Lodge, Cork.

Colonel Richard Townsend’s son Bryan (1648-1726) was a Commander in the British navy and MP for Clonakilty. He married Mary Synge, daughter of Edward, Bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross in 1663 and they had many children. In The Long Parliament, we are told of a portrait of Bryan: “If the very handsome picture at Castletownshend which has always borne his name is truly the portrait of Bryan, it most probably was painted while he was a naval officer, as he wears his own hair and not the voluminous wig in which gentlemen on land used to enshroud themselves.” I must look for this portrait next time we visit! Although it may have been destroyed, along with many papers and letters described in The Long Parliament, by fires in the castle.

Bryan was well-regarded by his neighbours:

“The laws made it almost impossible for any but a Protestant to hold land, so many of the Carbery Romanists, especially the O’Heas and O’Donovans, trusting in Bryan’s high character for integrity, gave their properties entirely into his hands, being obliged to do so without any written guarantee 1. At one time he had under his care upwards of £ 80,000 worth of property which he defended at considerable cost to himself, and when it was safe to restore it to the real owners he did so with all the arrears that had accrued while he held it. This fact was ascertained by the research of the late John Sealy Townshend .” [see 1]

Bryan and Mary’s son Richard (1684-1742) inherited Castletownshend , and was a Justice of the peace and high sheriff for County Cork. He married twice, first to another Mary Synge, daughter of Reverend Samuel, Dean of Kildare. His second wife was Elizabeth Becher from Skibbereen, County Cork.

The Townshends tell us in The Long Parliament about Jonathan Swift’s visit:

“Richard Townshend, of Castle Townshend, was born July 15, 1684, and succeeded to the estates on the death of his father Bryan, 1727 . It was at this period (*1) that Dean Swift spent some time in West Carbery . He stayed at Myros , but is said to have written his poem Carberiae Rupes in a ruined tower at Castle Townshend , still known as Swift’s Tower . It is also said that letters from the great Dean are still preserved at Castle Townshend , and that he named one of the houses in the village Laputa.” (*2)

The footnotes refer to *1: G. Digby Daunt and *2: Now Glen Barrahane, the seat of Sir J. J. Coghill , Bart .

Richard (1684-1742) and Elizabeth Becher’s son Richard (1725-1783) also served as MP and high sheriff. He married Elizabeth Fitzgerald, daughter of John Fitzgerald, the 15th Knight of Kerry (d. 1741). His father was Maurice Fitzgerald, the 14th Knight of Kerry, and Elizabeth’s brother was Maurice the 16th Knight of Kerry – there is a portrait of a Maurice Fitzgerald, Knight of Kerry, in the front hall, but I’m not sure which one is it. Richard’s portrait is in the dining room.

Next to the Knight of Kerry in the hall there is also a portrait of the Countess of Desmond, Katherine Fitzgerald (abt. 1504-1604), who lived to be over one hundred years old (some say she lived to be 140) and went through three sets of teeth. We came across her also in Dromana in County Waterford.

The Long Parliament describes:

“Richard Townshend married in 1752 Elizabeth , only daughter and heiress by survival of John FitzGerald, 15th Knight of Kerry, by whom he had one son and one daughter. Elizabeth FitzGerald’s only brother Maurice, 16th Knight of Kerry, had married his cousin Lady Anne Fitzmaurice, and died leaving no children, but even now he is remembered as ‘ the good Knight.’ He left all the Desmond estates in Kerry to the son of his sister Elizabeth Townshend.”

It may have been Richard Townsend (1725-1783) and his wife, the daughter of the 15th Knight of Kerry, who started to build the castle we see today. Keohane writes of the current castle at Castletownshend:

p. 314. “The Castle. A house of several parts, the seat of the Townshends. The earliest, described as ‘newly built’ in 1780 by the Complete Irish Traveller, is presumably the two-storey, five-bay rubble-stone centre block, with dormers over the upper windows and a two-storey rectilinear porch. Taller three-storey wings with battlements carried on corbelled cornices and twin- and triple-light timber-mullioned windows. The E. wing was perhaps built in the late 1820s; the W wing was added after a fire in 1852. Modest interior. Large low central hall with a beamed ceiling and walls lined with oak panelling and gilded embossed wallpaper. Taller dining room to the r., with a compartmented ceiling; a Neoclassical inlaid fireplace in the manner of Bossi, and a large Jacobean sideboard. C19 staircase with barley-twist type balusters.

Octagonal three-stage battlemented tower, 60 m west of the castle.” [5]

Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe continues: “Over the following centuries, members of the Townsend family served as high sheriffs of County Cork. In 1753 Richard Townsend was the office-holder and in 1785 Richard Boyle Townsend [1756-1826] was appointed to the position. In the 1870s Richard M.F. Townsend owned over 7,000 acres near Dingle in County Kerry, inherited from the FitzGerald family, Knights of Kerry. At that time, the estate of the late Rev. Maurice Townshend extended to over 8,000 acres in County Cork...” [4]

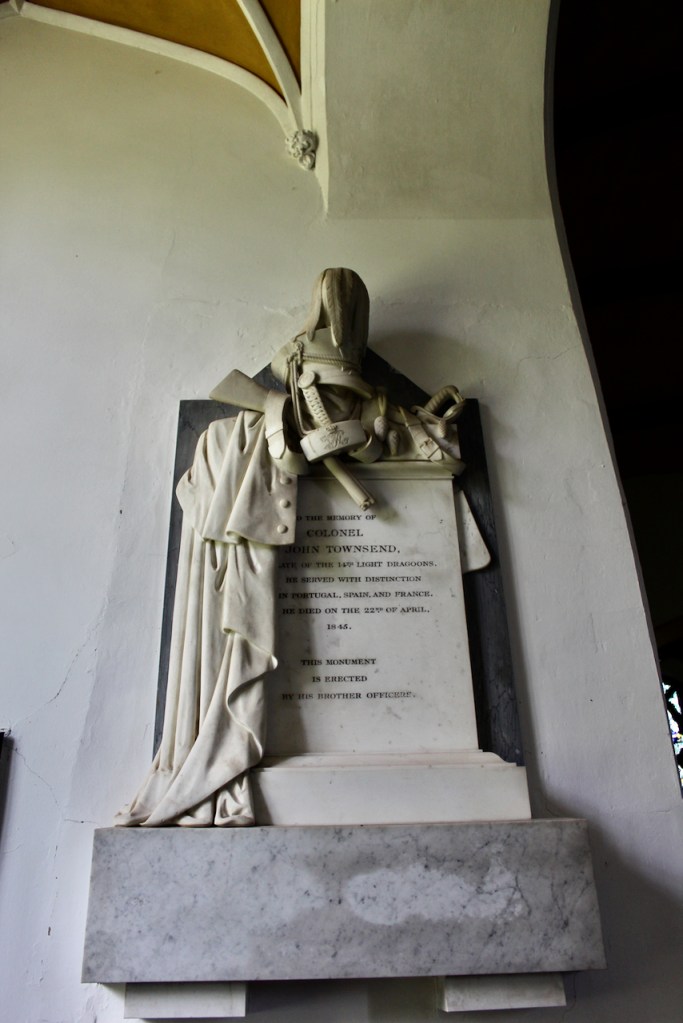

Richard Townsend and Elizabeth Fitzgerald’s son Richard Boyle Townsend (1753-1826) inherited Castletownshend. He was educated at Eton and Oxford. He married Henrietta Newenham. There is a fine portrait of their son Lieutenant-Colonel John Townsend, of the 14th Light Dragoons, who held the office of Aide-de-Camp to Queen Victoria.

Lt-Col John Townsend died in 1845, and the property passed to his brother, Reverend Maurice Townsend (d. 1872). Maurice married Alice Elizabeth Shute, heiress to Chevanage estate in Gloucestershire. Alice Elizabeth Shute was heiress by survival in her uncle Henry Stephens, and assumed his name. Maurice changed his name in 1870 to Maurice FitzGerald Stephens-Townshend (he was the one who added the ‘h’ in the name). She died at Castle Townshend aged only twenty-eight.

They had a son John Henry Townshend (1827-1869), who gained the rank of officer in the 2nd Life Guards. A fire occurred in 1852, during Reverend Maurice’s time in Castletownshend.

The website tells us about the fire: “Disaster struck again in 1852 when the newly built East Wing went up in flames. The blaze was so fierce that the large quantity of silver stored at the top of the wing ran down in molten streams. The family sent a Bristol silversmith to search the ruins and value the silver by the pound, which he did and promptly disappeared to America with a large part of it! The family still have some of that silver, all misshapen from the fire. The East Wing was rebuilt soon after the fire and The Castle has remained unchanged in appearance ever since.“

Reverend Maurice’s son predeceased him so Reverend Maurice’s grandson, Maurice Fitzgerald Stephens-Townshend (1865 – 1948) inherited Castletownshend in 1872 when he was still a minor. In the 1890s, the time of the Wyndham Act, 10,000 acres were put up for auction. The current owners still have the auction books. It was purchased by Charles Loftus Townsend (1861-1931).

Young Maurice married Blanche Lillie Ffolliot. She was an only child and brought money with her marriage, and Maurice was able to buy back the castle. The castle passed to their daughter, Rosemarie Salter-Townshend. She began to rent out holiday homes in Castletownshend. Her husband, William Robert Salter, added Townshend to his surname. It was their daughter Anne who modernised the castle, putting in central heating etc.

The website continues: “Full of character and old-world charm, The Castle offers a welcoming retreat from everyday life. There are lots of things to do in the local area, like whale-watching and kayaking. Or, you can simply rest and recharge your batteries in the unique surroundings. After enjoying a complimentary breakfast, stroll through the winding pathways of our historic grounds, discovering ivy-covered ruins and their stories along the way. Then, as the sun sets, sit out the front with a drink in your hand, watching the boats in the harbour sway gently back and forth.

While you are a guest in our family’s home, the only thing on your To Do list is to relax. We will look after the rest.“

[1] The website adds that much has been written about the Townshend family and The Castle over the years, and this rich history is documented in great detail. An Officer of the Long Parliament, edited by Richard and Dorothea Townsend (London Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press Warehouse, Amen Corner, E.C.,1892) is an account of the life and times of Colonel Richard Townesend and a chronicle of his descendants.

[2] see Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh. Burke’s Irish Family Records. London, U.K.: Burkes Peerage Ltd, 1976.

[3] p. 1035, volume 19, Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. Dictionary of National Biography, 1921–1922. Volumes 1–22. London, England: Oxford University Press.

[4] O’Hea O’Keeffe, Jane. Voices from the Great Houses: Cork and Kerry (Mercier Press, Cork, 2013).

[5] Keohane, Frank. The Buildings of Ireland: Cork City and County. Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2020.