Open dates in 2026: May 1-31, June 1-10, Aug 15-23, Oct 1-20, 9am-1pm

Fee: house, adult/OAP/student €5, garden, adult/OAP/student €5, child free

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

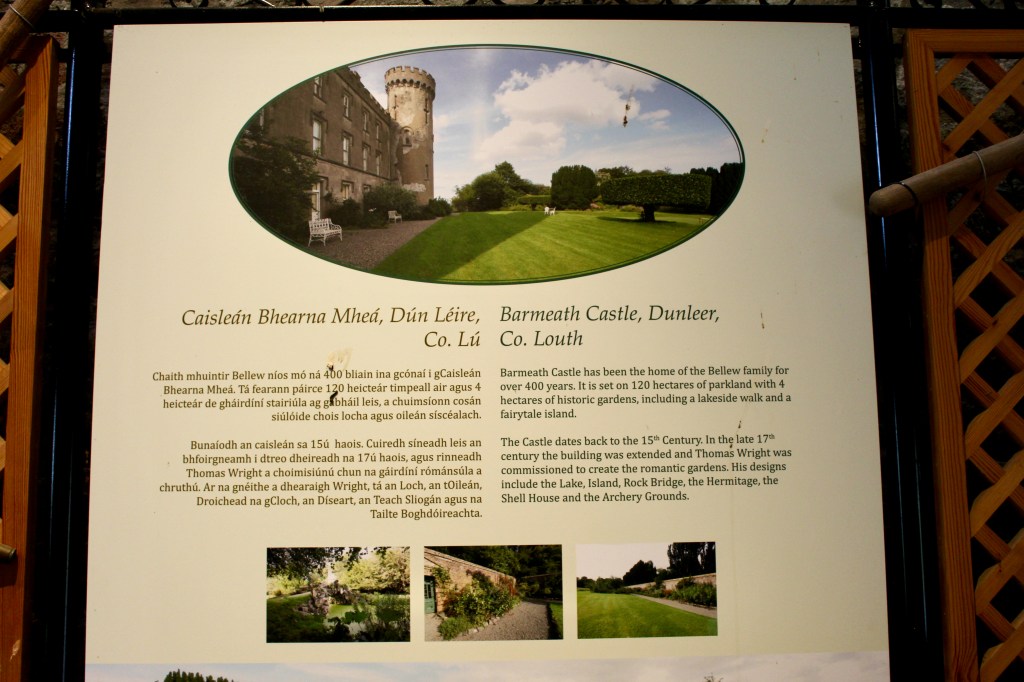

I was excited to see Barmeath Castle as it looks so impressive in photographs. We headed out on another Saturday morning – I contacted Bryan Bellew in advance and he was welcoming. We were lucky to have another beautifully sunny day in October.

We drove up the long driveway.

The Bellew family have lived in the area since the 12th century, according to Timothy William Ferres. [2] The Bellews were an Anglo-Norman family who came to Ireland with King Henry II. The Castle was built in the 15th century by previous owners, the Moores, as a tower house. The Moores were later Earls of Drogheda, and owned Mellifont Abbey after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, which became the Moore family home until 1725. [3] Edward Moore (c.1530–1602), ancestor of the Earl of Drogheda, served in the English garrison at Berwick on the Scottish border during the 1550s before going to Ireland c.1561, probably having been encouraged to do so by his kinsman Henry Sidney, who had held senior appointments in Ireland in the late 1550s.

We were greeted outside the castle by Lord and Lady Bellew – the present owner is the 8th Lord Bellew of Barmeath. I didn’t get to take a photograph of the house from the front as we immediately introduced ourselves and Lord Bellew told us the story of the acquisition of the land by his ancestor, John Bellew.

The name “Barmeath” comes from the Irish language, said to derive from the Gaelic Bearna Mheabh or Maeve’s Pass. Reputedly Queen Maeve established a camp at Barmeath before her legendary cattle raid, which culminated in the capture the Brown Bull of Cooley, as recounted in the famous epic poem, The Tain.

The Historic Houses of Ireland website tells us:

“Barmeath Castle stands proudly on the sheltered slopes of a wooded hillside in County Louth, looking out over the park to the mountains of the Cooley Peninsula and a wide panorama of the Irish sea. The Bellew family was banished to Connacht by Cromwell but acquired the Barmeath estate in settlement of an unpaid bill.” [4]

John Bellew fought against Cromwell and lost his estate in Lisryan, County Longford, and was banished to Connaught.

Theobald Taaffe (d. 1677) 1st Earl of Carlingford, County Louth, also lost lands due to his opposition to Cromwell and the Parliamentarians and loyalty to King Charles I. The Taaffes had also lived in Ireland since the twelfth or thirteenth century, and owned large tracts of land in Louth and Sligo. Theobald Taaffe, who was already 2nd Viscount, was advanced in 1662 to be 1st Earl of Carlingford. He engaged John Bellew as his lawyer to represent him at the Court of Claims after the Restoration of King Charles II (1660).

Theobald Taaffe’s mother was Anne Dillon, daughter of Theobald Dillon 1st Viscount of Costello-Gallin, County Mayo. John Bellew, while banished to Connaught, married a daughter of Robert Dillon of Clonbrock, County Galway. The Clonbrock Dillons were related to the Viscounts Dillon, so perhaps it was this relationship which led Lord Carlingford to engage John Bellew as his lawyer.

Bellew won the case and as payment, he was given 2000 of the 10,000 acres which Lord Carlingford won in his case, recovered from Cromwellian soldiers and “adventurers” who had taken advantage of land transfers at the time of the upheaval of Civil War. Lord Carlingford may have taken up residence in Smarmore Castle in County Louth, which was occupied by generations of Taaffes until the mid 1980s and is now a private clinic. A more ancient building which would have been occupied by the Taaffe family is Taaffe’s Castle in the town of Carlingford.

John Bellew served as MP for County Louth.

The Baronetcy of Barmeath was created in 1688 for Patrick Bellew (d. 1715/16), the lawyer John’s son, for his loyalty to James II. [see 2] John Bellew’s daughter Mary married Gerald Aylmer 2nd Baronet of Balrath, County Meath. His son Christopher gave rise to the Bellews of Mount Bellew in County Galway and established the market town, Mount Bellew.

Patrick, who was High Sheriff of County Louth in 1687, married Elizabeth Barnewall, daughter of Richard, 2nd Baronet Barnewall of Crickstown, County Meath (a little bit of a ruin survives of this castle). His son John (c. 1660-1734) inherited Barmeath and the title, 2nd Baronet of Barmeath.

The castle we see today was built onto the 15th century tower house, in 1770, for Patrick Bellew (c. 1735-1795) 5th Baronet, and enlarged and castellated in 1839 by Sir Patrick Bellew (1798-1866), 7th Bt, afterwards 1st Baron Bellew.

Casey and Rowan speculate: “An explanation for the quality of the interiors at Barmeath may lie in the remarkable propensity which Bellews displayed for marrying heiresses in the eighteenth century. In 1688 Patrick Bellew of Barmeath was created a Baronet of Ireland. His son Sir John Bellew, the second Baronet, married an heiress; so did the third Baronet, Sir Edward, who died in 1741.”

The 2nd Baronet married first, in 1685, Mary, daughter of Edward Taylor, who was eventually heiress of her brother, Nicholas Taylor. He married secondly, Elizabeth, daughter of Edward Curling, storekeeper of Londonderry during the siege of that city.

Edward the 3rd Baronet married Eleanor, eldest daughter and co-heir of Michael Moore of Drogheda.

Patrick Bellew (c. 1735-1795) 5th Baronet inherited Barmeath and also owned considerable land in County Galway, which he sold in August 1786 to his Galway Bellew cousins, with whom he maintained close contact. He married Mary, daughter and co-heiress of Matthew Hore, of Shandon, County Waterford.

The Bellews are historically a prominantly Catholic family. Patrick Bellew the 5th Baronet was active in promoting the cause of Catholics in Ireland. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us:

“Politically assertive, Sir Patrick was active in catholic politics from the early 1760s, reassuring the government of catholic loyalty and petitioning for catholics to be allowed enter the army in 1762. As the gentry began to supplant the Dublin middle classes in the Catholic Committee in the 1770s, he increasingly became involved in its affairs and was appointed to its select committee in 1778. In 1778 he contributed and raised funds for catholic agitation and spent much of the year in England lobbying for repeal of the penal laws; his efforts were rewarded with the passing of the 1778 relief act.” [5]

Bence-Jones writes in his Life in an Irish Country House that it was Patrick Bellew, the 5th Baronet, who remodelled the house and had the decorative library ceiling made. [6]

The rococo interior details pre-date the exterior Gothicization of Barmeath Castle. The egg-and-dart mouldings around the first floor doors, Corinthian columns and staircase all seem to date, according to Casey and Rowan, to approximately 1750, which would have been the time of the 4th and 5th Baronets; John the 4th Baronet (1728-50) died of smallpox, unmarried, and the title devolved upon his brother, Patrick (c. 1735-95), 5th Baronet. The library might be from a little later. Casey and Rowan describe it:

“The finest room, the library, set on the NE side of the house above the entrance lobby, is possibly a little later. Lined on its N and S walls with tall mahogany break-front bookcases, each framed by Ionic pilasters and surmounted by a broken pediment, it offers a remarkable example of Irish rococo taste. The fretwork borders and angular lattice carving of the bookcases are oriental in inspiration and must reflect the mid-C18 taste for chinoiserie, made popular by pattern books such as Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director (1754). The ceiling has a deep plasterwork cove filled with interlaced garland ropes, a free acanthus border, oval motifs and shells set diagonally in the corners. Free scrolls, flowers and birds occupy the flat area with, in the centre, a rather artless arrangement of Masonic symbols, including three set-squares, three pairs of dividers, clouds and the eye of God.” [7]

The Dictionary of Irish Biography continues: “Sir Patrick was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir Edward Bellew (1758?–1827), 6th baronet. Active in the Catholic Committee from the 1780s, Sir Edward was named as a trustee of Maynooth College at its foundation in 1795. He continued to work for emancipation after the union and was one of the delegates who presented the Irish catholic petition to parliament in 1805. Representative of the aristocratic tendency on the Catholic Board, he disapproved of the populist style of agitation of Daniel O’Connell, and in December 1816 he seceded from the board in protest at O’Connell’s uncompromising opposition to a government veto on episcopal appointments.” [see 5]

The 6th Baronet continued the fortuitous tradition of marrying an heiress as he married, in 1786, Mary Anne, daughter and sole heir of Richard Strange, of Rockwell Castle, County Kilkenny. Casey and Rowan write that due to this marriage, “it was no doubt his accumulated wealth and that of his bride…which enabled his son, Patrick, the first Lord Bellew, to recast the house in its elaborate castle style.“

The title Baron Bellew of Barmeath was created in 1848 for Patrick Bellew, previously 7th Baronet, who represented Louth in the House of Commons as a Whig, and also served as High Sheriff and Lord Lieutenant of County Louth. He was Commissioner of National Education in Ireland between 1839 and 1866. He married Anna Fermina de Mendoza, daughter of Admiral Don José Maria de Mendoza y Rios of Spain.

It was probably his elevation from Baronet to Baron which encouraged Patrick Bellew “to turn his sensible mid-Georgian home into a Norman pile of straggling plan and flamboyant silhoutte,” as Christine Casey or Allistair Rowan write in The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster (1993).

Part of a genuine tower house is still part of the castle, detectable by the unusual thickness of the window openings at the northeastern corner of the building. [see 7] Before the 1839 enlargement, it was a plain rectangular block, two rooms deep and three storeys high, with seven windows across the front, and a central main door.

Mark Bence-Jones suggests in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses that the design for the enlargement may have been by John Benjamin Keane. [8] Lord Bellew recalled Mr. Bence-Jones’s visit to the house! However, Casey and Rowan write that the Hertfordshire engineer Thomas Smith (1798-1875), who had also worked in Dundalk, designed of the Neo-Norman castle.

Smith also worked on Castle Bellingham in County Louth (another magnificent castle which is available for weddings, see my entry under “Places to visit and stay in County Louth https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-louth-leinster/) [9], and Braganstown House in County Louth (privately owned).

Casey and Rowan tell us that Smith replaced the eaves cornice of the house with battlements and added round towers at each end of the original front of the house.

The round towers rise a storey higher than the rest of the house and have arrow loops and slit windows.

A long two-storey turreted wing was added, with bartizans, diagonal buttresses, a central projecting section and tall mullioned lights.

Casey and Rowan continue their description:

“On the north, Smith provided a Norman gateway to the yard, with a pair of dumpy machicolated towers, and he also added, to the northwest corner of the house itself, a new entrance tower, rectangular in plan, with a circular stair turret, which gives an asymmetrical accent to the entire composition.” [see 7]

At this time, Bence-Jones tells us, the castle kept its Georgian sash-windows, though some of them lost their astragals later in the nineteenth century. The entire building was cased in cement, lined to look like blocks of stone, and hoodmouldings were added above the windows.

The property passed to the 1st Baron’s son, Edward Joseph Bellew (1830-1895), who became 2nd Baron Bellew of Barmeath.

The Bellews brought us inside, and Lady Bellew had us sign the visitors’ book. I told them I am writing a blog, and mentioned that we visited Rokeby Hall and met Jean Young, who had told us that she is reading the archives of Barmeath. Lord Bellew proceeded with the tour.

Casey and Rowan describe the interior:

” A neo-medieval lobby off the porte cochére, with a heavy flat lierne vault and central octagonal boss, is the only part of the house which attempts to sustain the style of the exterior. The rest of Barmeath is finished in a fine taste, mostly with mid-eighteenth century rococo classical details or, on the drawing room floor, in light Tudor manner. The core of the house is the hall and staircase which occupy the centre of the main range and are linked by an arcaded screen. The room is square in plan, lit by an Ionic Palladian window with a boldly scaled modillion cornice.“

On the staircase, we chatted about history and enjoyed swapping stories. Lord Bellew pointed out the unusually large spiral end of the mahogany staircase handrail, perpendicular to the floor – it must be at least half a metre in diameter. The joinery of the staircase is eighteenth century, with Corinthian balusters.

Mark Bence-Jones describes it:

“Staircase of magnificent C18 joinery, with Corinthian balusters and a handrail curling in a generous spiral at the foot of the stairs, opening with arches into the original entrance hall; pedimented doorcases on 1st floor landing, one of them with a scroll pediment and engaged Corinthian columns.”

Casey and Rowan tell us that the long first-floor drawing room and a second sitting room at the south end of the front were redesigned by Smith. They tell us “they have pretty diaper reeded ceilings of a neo-Elizabethan pattern, with irregular octagonal centres.” Bence-Jones continues his description:

“Long upstairs drawing room with Gothic fretted ceiling. Very handsome C18 library, also on 1st floor; bookcases with Ionic pilasters, broken pediments and curved astragals; ceiling of rococo plasterwork incorporating Masonic emblems. The member of the family who made this room used it for Lodge meetings. When Catholics were no longer allowed to be Freemasons, [in accordance with a Papal dictat, in 1738], he told his former brethren that they could continue holding their meetings here during his lifetime, though he himself would henceforth be unable to attend them.”

When in the library, I told Lord Bellew that I’d read about his generous ancestor who continued to allow the Freemasons to meet in his home despite his leaving the organisation. Lord Bellew pointed out the desk where Jean works when she visits the archives. What a wonderful room in which to spend one’s days!

Next we headed outside, and Lord Bellew took us on a tour of the garden. Barmeath Castle is set on 300 acres of parkland with 10 acres of gardens, including a lake with island. There’s a walled garden and an archery ground. The main design of the garden is by Thomas Wright who came to Ireland in 1745. The Boyne Valley Garden Trail website tells us that the gardens were abandoned between 1920 and 1938, but were brought back to life by Jeanie Bellew, the present incumbent’s grandmother. These improvements continue with Rosemary and Bryan Bellew. [10]

I found a short video of Lord Bellew discussing the castle on youtube, and he tells how his son made the “temple” on the island, in return for the gift of a car! The temple is very romantic in the distance, and extremely well-made, looking truly ancient.

The Irish Historic Houses website tells us about the gardens:

“The lake and pleasure grounds were designed by the garden designer and polymath, Thomas Wright of Durham (1711-1785), who visited Ireland in 1746 at the invitation of Lord Limerick and designed a series of garden buildings on his estate at Tollymore in County Down. Wright explored ‘the wee county’ extensively and his book “Louthiana”, which describes and illustrates many of its archaeological sites, is among the earliest surveys of its type. His preoccupation with Masonic ‘craft’ indicates that Wright is likely to have been a Freemason, which probably helped to cement his friendship with the Bellew of the day [this would have been John the 4th Baronet]. He may well have influenced the design for the Barmeath library and indeed the mid-eighteenth century house.

“Wright’s highly original layout, which is contemporary with the house, is remarkably complete and important, and deserves to be more widely known. It includes a small lake, an archery ground, a maze, a hermitage, a shell house and a rustic bridge, while the four-acre walled garden has recently been restored.” [11]

We walked along the lake to the specially created bridge by Thomas Wright. We walked over it, and I marvelled at how it stands still so solid, after two hundred and fifty years!

Thomas Wright also designed the perhaps more famous “Jealous Wall” and other follies at Belvedere, County Westmeath. He may have designed them especially for Robert Rochfort, Lord Belvedere, or else Lord Belvedere used Wright’s Six Original Designs of Grottos (1758) for his follies. The Jealous Wall was purportedly built to shield Rochfort’s view of his brother George’s house, Rochfort House (later called Tudenham Park).

The lake was created to look like a river, and indeed it would have fooled me!

The current owners have been working to restore the four acre walled garden. Lord Bellew and I discussed gardening as he showed us around.

A cottage in the garden contains beautiful painted walls:

The walls depict scenes of Venice.

The gardens are open to the public as part of the Boyne Valley Gardeners Trail. [12] More visitors were scheduled to arrive so Lord Bellew saw us to our car and we headed off.

Later, on a visit to the Battle of the Boyne museum, we saw the Bellew regalia pictured on a soldier.

[2] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/search/label/County%20Louth%20Landowners

[3] http://www.turtlebunbury.com/history/history_family/hist_family_mooredrogheda.html

[4] http://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Barmeath%20Castle

[5] https://www.dib.ie/biography/bellew-sir-patrick-a0561

[6] p. 38. Bence-Jones, Mark. Life in an Irish Country House. Constable and Company Ltd, London, 1996.

[7] p. 152-154. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

[8] Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses.(originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[9] https://www.bellinghamcastle.ie

[10] https://boynevalleygardentrail.com/portfolio/barmeath-castle-dunleer-co-louth/

[11] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Barmeath%20Castle

[12] https://www.garden.ie/gardenstosee/barmeath-castle/

© Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com