Open dates in 2026: Apr 1-Oct 31, 10am-5pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student €6, child free with an adult

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

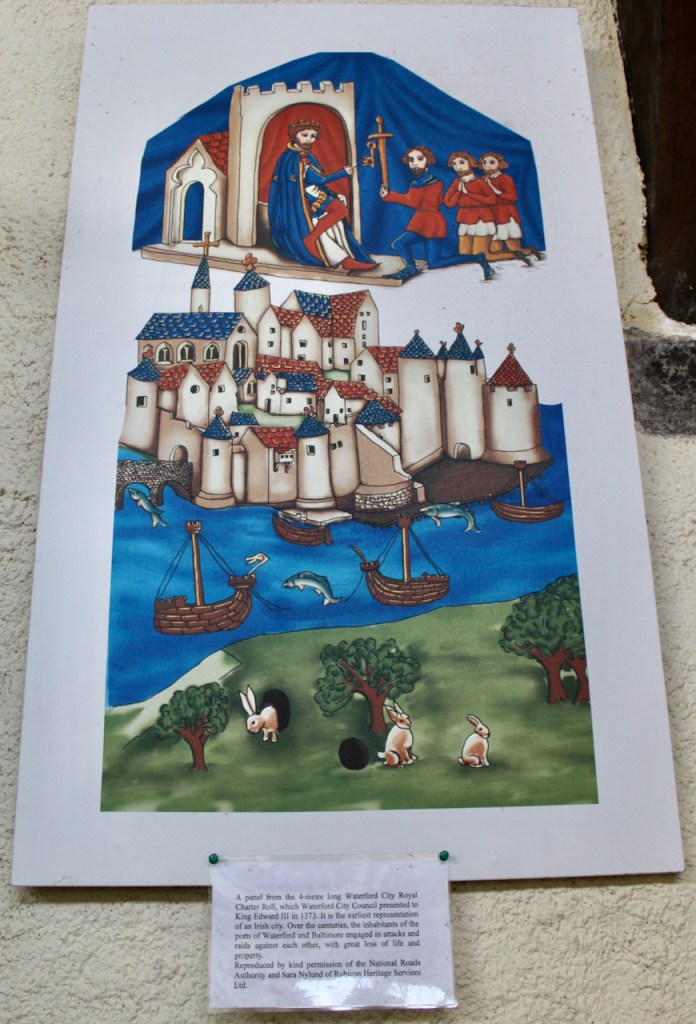

Dunasead Castle, also known as Dún a Séad (“Fort of the Jewels”), Dunashad or Baltimore Castle, lies in the town of Baltimore in County Cork.

The website tells us that the site of Dún na séad Castle has been fortified for a very long time. The first fortification might have been a ring fort. After that an Anglo-Norman castle was built here in 1215. In 1305 that castle was taken and destroyed by the MacCarthys. Subsequently the O’Driscolls took possession of the site and built a castle.

The website tells us that the present Dún na séad Castle was built in the 1620s by the O’Driscolls, but Frank Keohane writes that it was built by Thomas Crooke before 1610 near an earlier O’Driscoll castle. Frank Keohane writes in his The Buildings of Ireland: Cork City and County:

“Baltimore or Dunasead Castle. Early C17 two-storey gable-ended block with an attic, set on a rock overlooking Baltimore Harbour. An O’Driscoll castle NE of the present building was occupied by an English force in 1602 after the Battle of Kinsale, during which it was substantially demolished. Sir Fineen O’Driscoll then leased Baltimore and its ‘castle’ to Thomas Crooke and William Coppinger. Crooke, who established an English settlement, appears to have built the present castle before 1610, possibly incorporating features such as the window surrounds from the O’Driscoll castle.” [1]

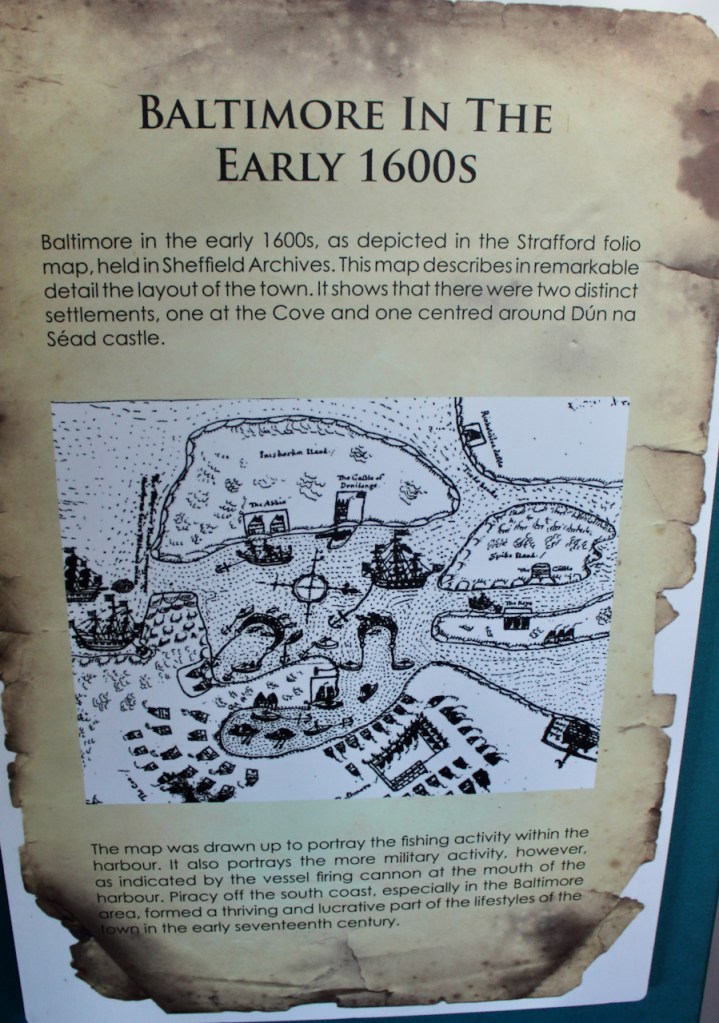

Keohane tells us: “[Baltimore is] a small pretty village… overlooking a broad deep bay sheltered from the Atlantic by Sherkin Island. An English settlement was first established here in the early C17 by Sir Thomas Crooke, later passing to Sir Walter Coppinger. By 1629 English settlers had built sixty houses here.“

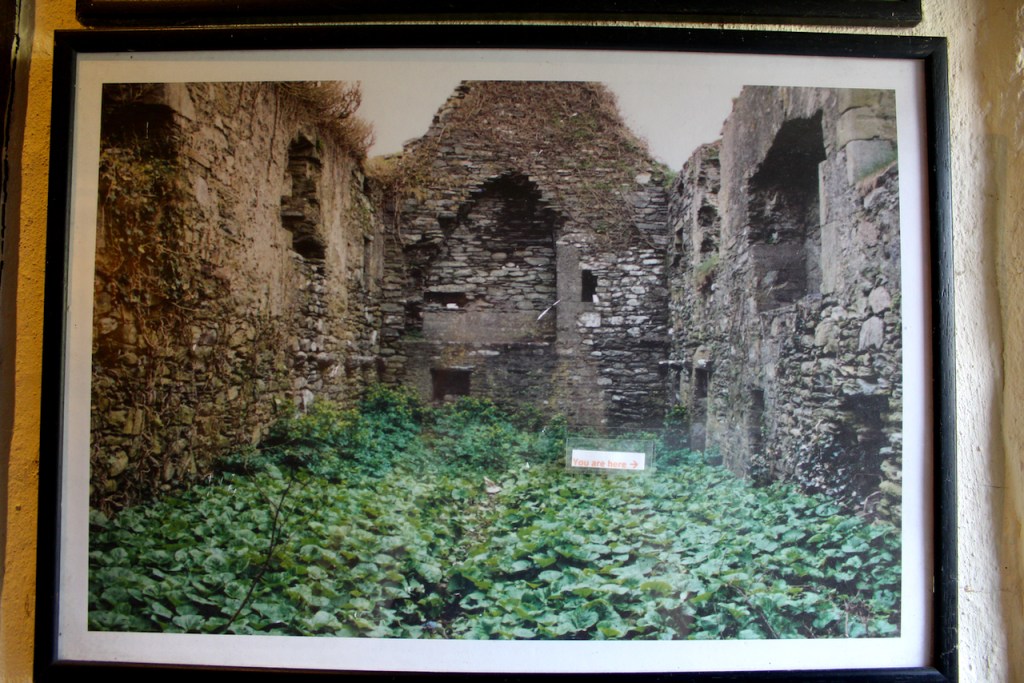

Between 1997 and 2005 the ruined castle was rebuilt as a private residence. At present it is a small museum. The owners, the McCarthys, have done an amazing job restoring the castle and it is also their home.

Keohane continues: “Restored as a dwelling in 1997-2003. The contemporary interventions are well considered, with minimal conjecture and cleanly distinct materials….The castle is approached across a small enclosed bawn on the east or landward side. The lower floor served as stores, with living quarters above. Wall-walks behind parapets are provided on the long sides. These give access to a square bartizan over the SW corner; another bartizan was probably provided on the opposing NE corner. The West side is blind at the ground level but has generous two and three light first floor windows (all now missing mullions and transoms), with ogee heads, sunken spandrels and curious curved hoodmould terminals similar to those at Clodagh Castle (Crookstown). On the east side, two great reconstructed chimneystacks sit on corbels at first-floor level. Here, small rectangular lights serve the ground-floor rooms, while the first-floor rooms have wider windows. A narrow first-floor door at the south end led to a now destroyed garderobe turret. The upper rooms were approached by an internal stair rather than a forestair. Markings in the plaster suggest that there were three major rooms, divided by partitions, with attics at each end. The central “hall” had good sandstone window dressings with neat roll mouldings, and a fireplace with remains of a moulded and chamfered limestone jamb. A solar or parlour was provided to the south. The north room has a bread oven and a slop stone in addition to its fireplace, indicating use as a kitchen.”

But let us backtrack to the Castle’s fascinating history.

The information boards tell us that in 1215 Robert de Carew, Lord Sleynie, built the castle, and that his mother was a daughter of the chieftain Dermod MacCarthy of Cork.

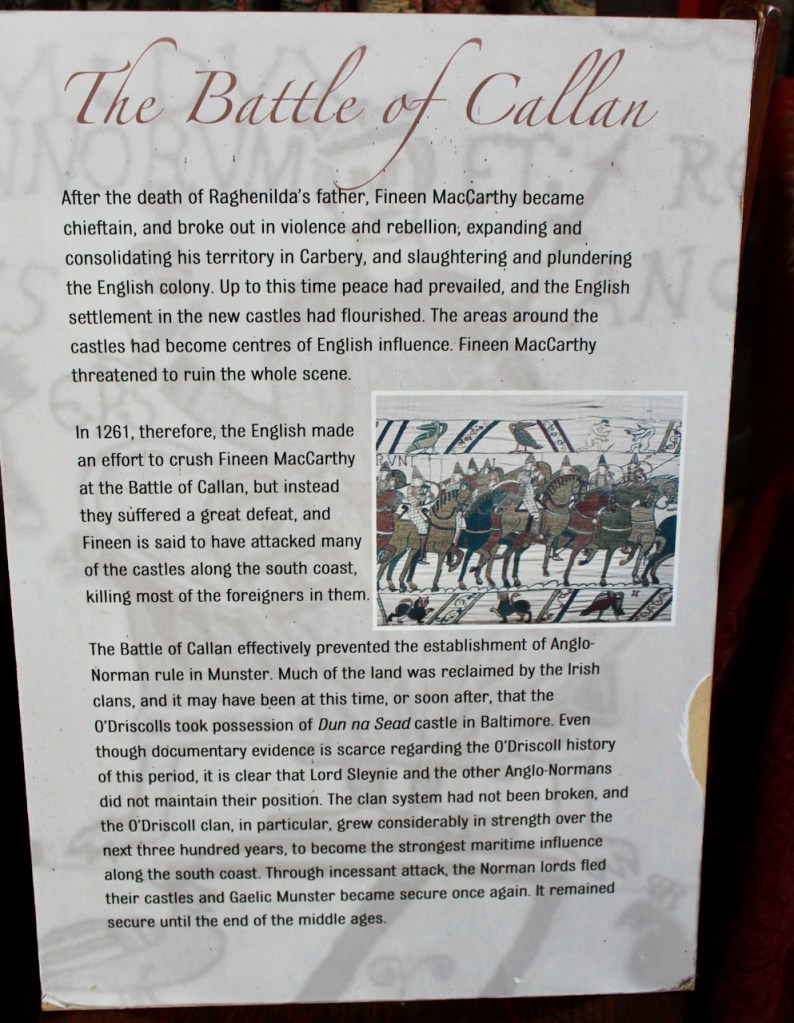

After the Battle of Callan, the O’Driscoll family took possession of the castle at Baltimore. The O’Driscolls were fishermen and pirates.

The website tells us that the O’Driscolls were constantly under pressure from encroachments by Anglo-Norman settlers and rival Gaelic clans on their territory and trade interests, which resulted in the castle being attacked and destroyed numerous times in the following centuries.

The O’Driscolls imposed taxes on harbour trade and traffic in order to support their opulent lifestyle. They had no authority from the crown to impose such taxes, so in 1381 King Richard II appointed admirals for the ports of county Cork in an attempt to deal with the pirate menace to merchant shipping in the area. The admirals were commissioned to deal in particular with the O’Driscolls of Baltimore “who constantly remained upon the western ocean, preying in passing ships.” [2]

In the early 1600s Fineen O’Driscoll of Dún na Séad castle pledged loyalty to the Crown of England. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I.

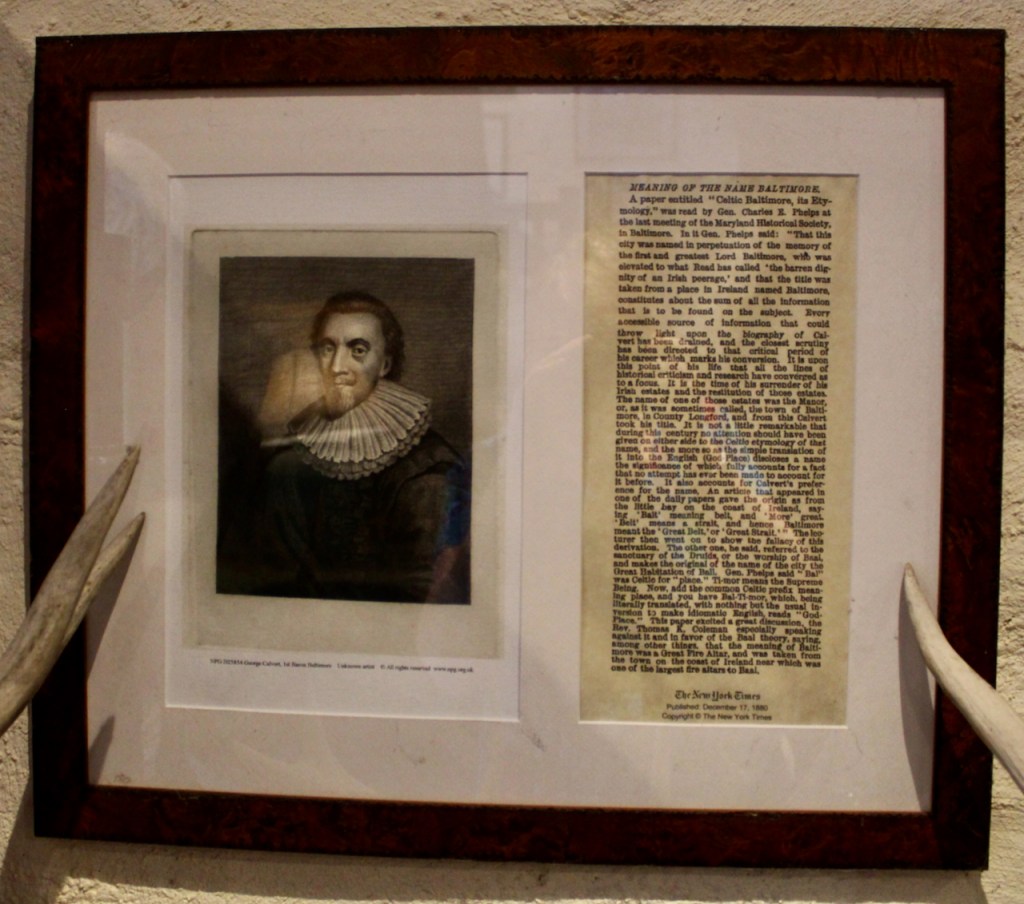

In 1606 Thomas Crooke (b. 1574) was granted Baltimore Castle and the town of Baltimore as well as lands and islands formerly belonging to the O’Driscolls, in order to secure the area for the Crown and establish a Protestant colony. Bernie McCarthy tells us in her book that there is no evidence of the relationship between Fineen O’Driscoll and Thomas Crooke, and we do not know if the O’Driscolls stood aside willingly or whether Crooke had to engage in force to obtain the property. The portrait in the information board is not of Thomas Crooke but is of typical attire of an English planter at the time.

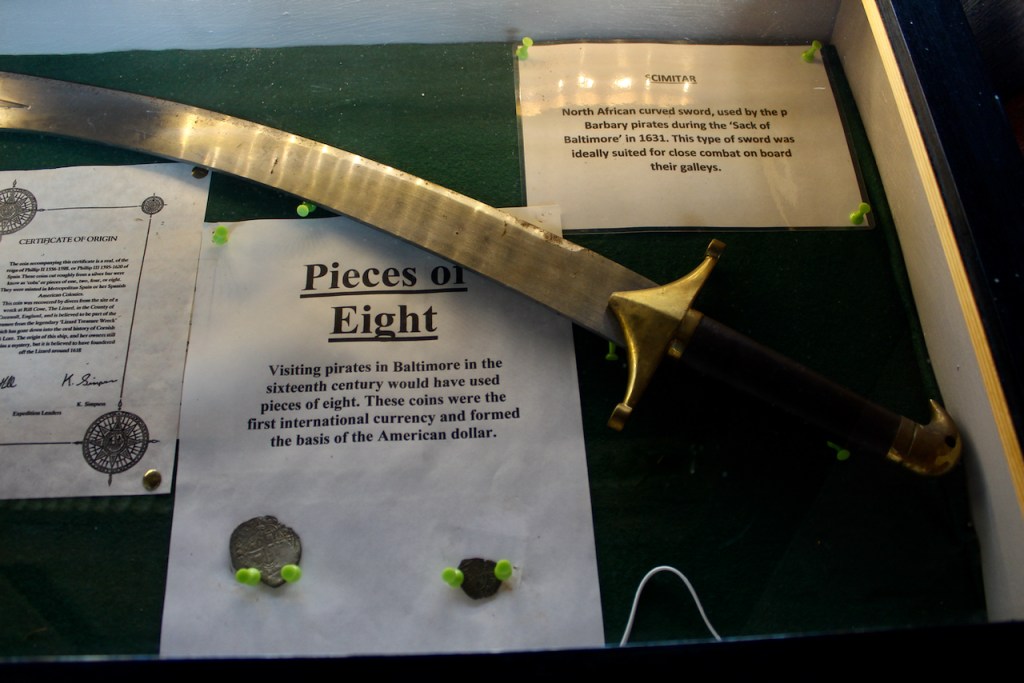

Crooke was meant to represent the Crown but he became involved in piracy, co-operating with English and Flemish pirates and profiting from their spoils.

There was, however, a system the Crown used for legitimising piracy by a system of “privateering” which was sanctioned by the State. A Privateer obtained a license, or letter of “Marque” to use their ships as a man-o-war against the State’s enemies in times of war. The marque permitted vessel owners to seize Crown enemies, acquire their cargo and make a profit. The captured ships were taken before the Prize Court and the captured cargo was referred to as the “prize,” and the privateer was awarded 90% of the prize, with 10% of the value going to the National Prize Fund. [3] Privateers took advantage of this legitimacy to capture illegitimate bounty, but in the case of Crooke, his work establishing a colony made the Crown turn a blind eye to his piracy.

Pirates would dock in Baltimore to repair ships or gather supplies, and this led to proliferation of taverns and brothels in Baltimore. A list of goods brought to Baltimore around 1615 by the pirate Campane includes wax, pepper, 100 Barbary hides, a chest of camphor, tobacco, cloves, elephants’ teeth (probably tusks), Muscovy hides, a chest of chenery roots and canopies of beds from the Canary Islands. [4]

In 1613, Baltimore was enabled by charter to send two MPs to the Dublin Parliament. Thomas Crooke was elected MP. Ironically, it was this parliament which introduced the Irish Statue against piracy.

By 1626, Crooke feared the consequences of foreign pirates, and he petitioned the House of Lords for protection of Baltimore. Unfortunately, any protection proved inadequate.

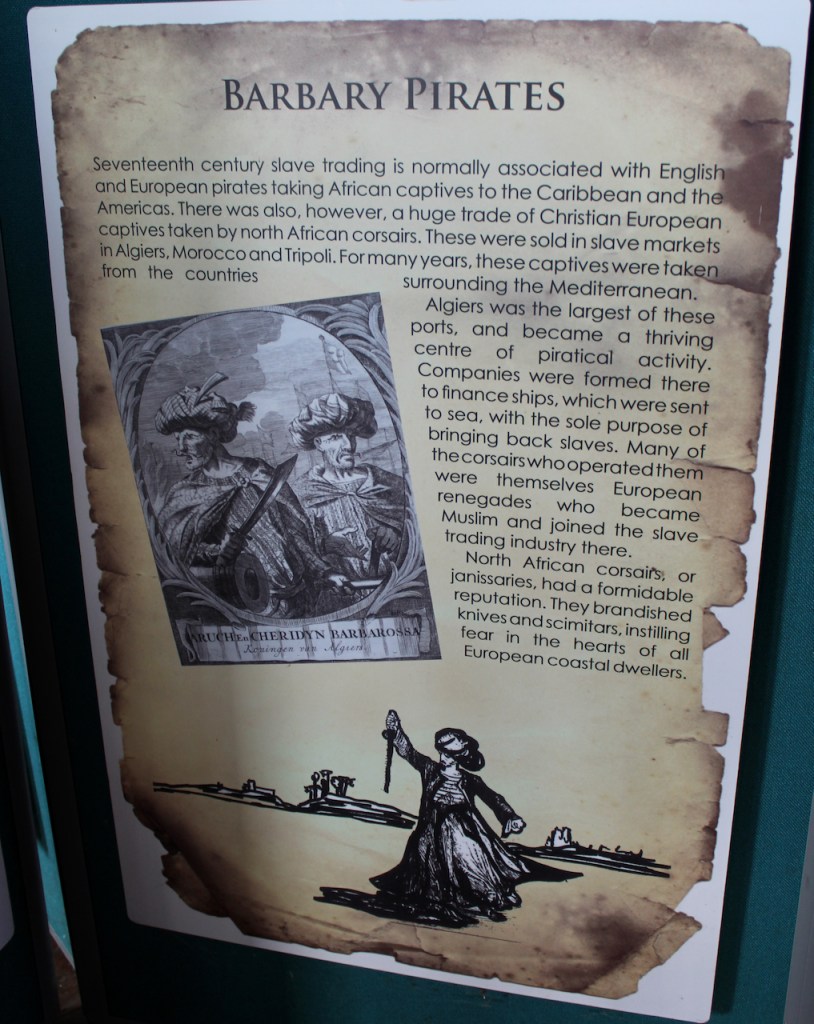

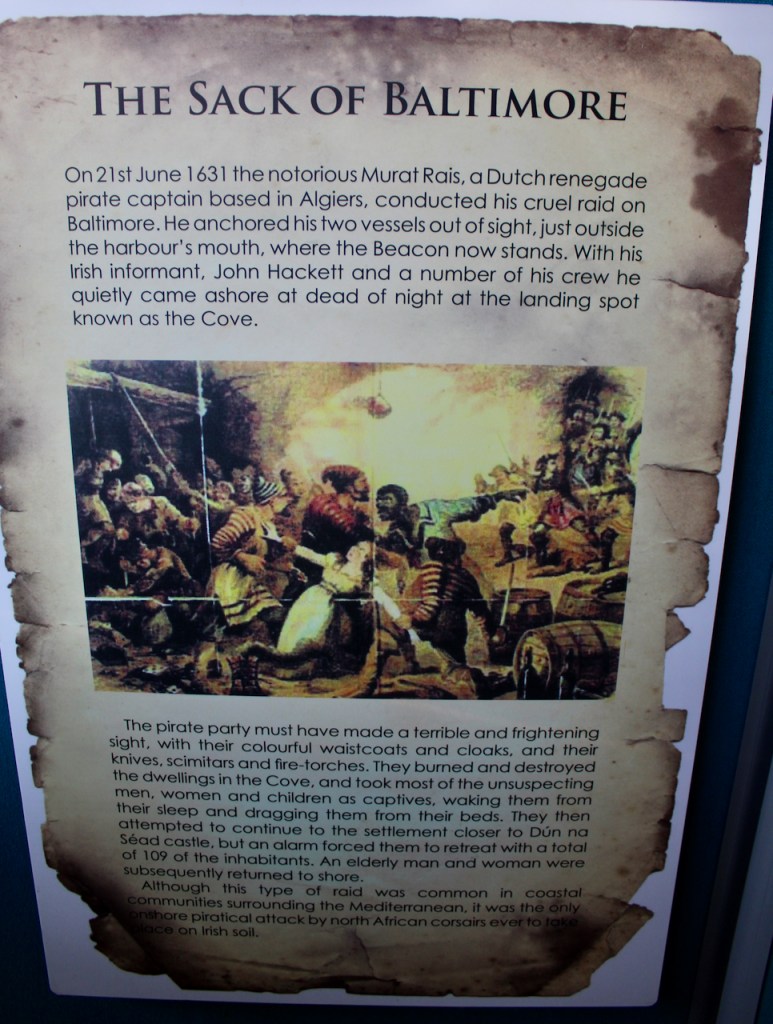

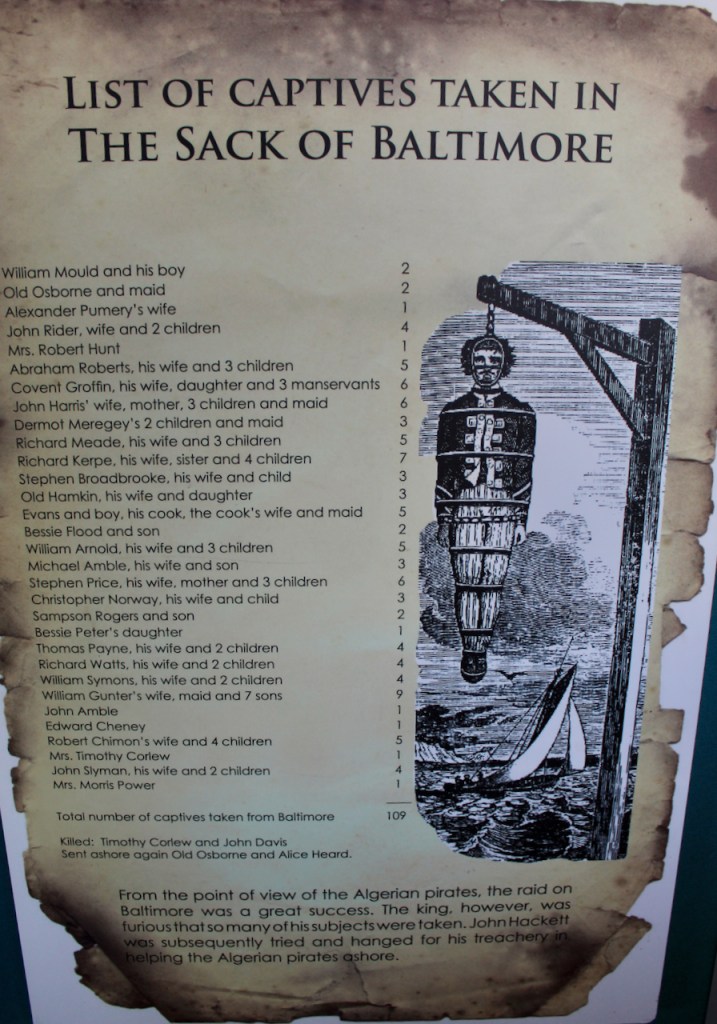

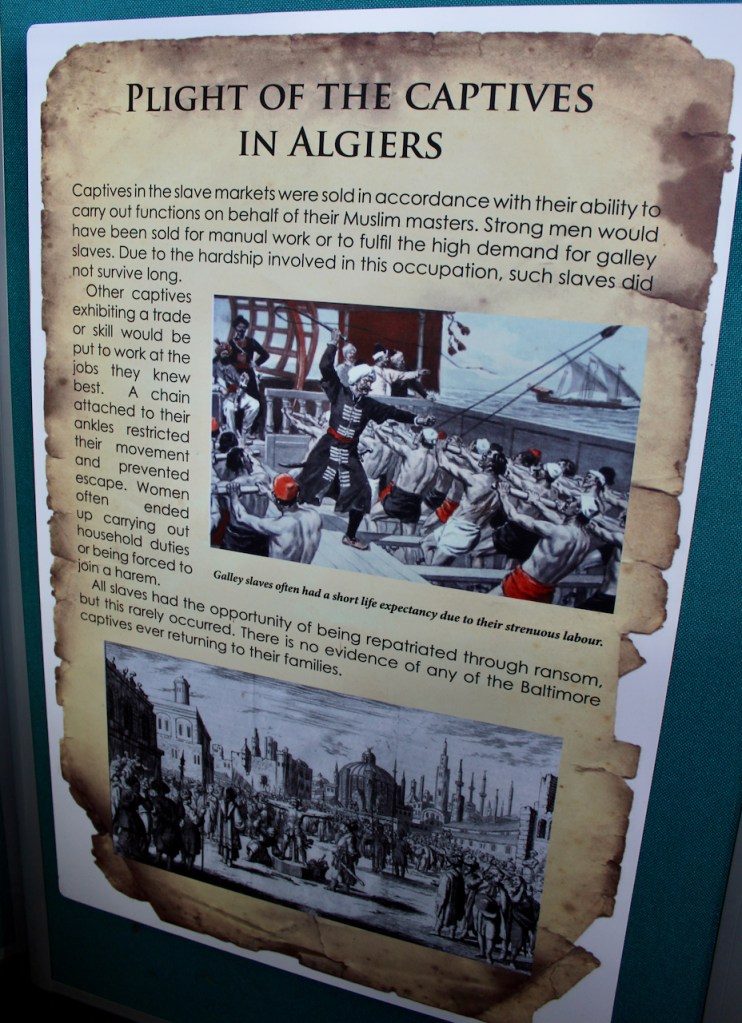

In 1631 a band of pirates from Algiers took 107 captives to a life of slavery in North Africa. Bernie McCarthy of Baltimore Castle has written a book called Pirates of Baltimore from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century, Baltimore Castle Publications, 2012, which informs the educational material in the museum. [see 2]

At the time of the raid, Baltimore Castle was occupied by Thomas Bennett. He wrote to James Salmon of Castlehaven, County Cork, in an effort to send a ship from there to try to intercept the captives, and the Lord President of Munster ordered two of the king’s ships of war, the Lions Whelps, which were in Kinsale at the time, to go to the rescue, but none of the attempts were successful. [5]

In 1624 the House of Lords in London instructed the House of Commons to grant Letters Patent for a collection to be made for the redemption of English captives, and an “Algerian Duty” was set aside from Customs tax. There were also ransom charities, but at the same time, it was feared that paying ransoms would encourage the taking of captives. An account of Barbary pirates was written by a French priest who worked in Algeria trying to negotiate the release of captives, Pierre Dan, “Histoire de Barbarie et de ses corsairs.” He worked for the Catholic charity the Order of the Holy Trinity and Redemption of Slaves.

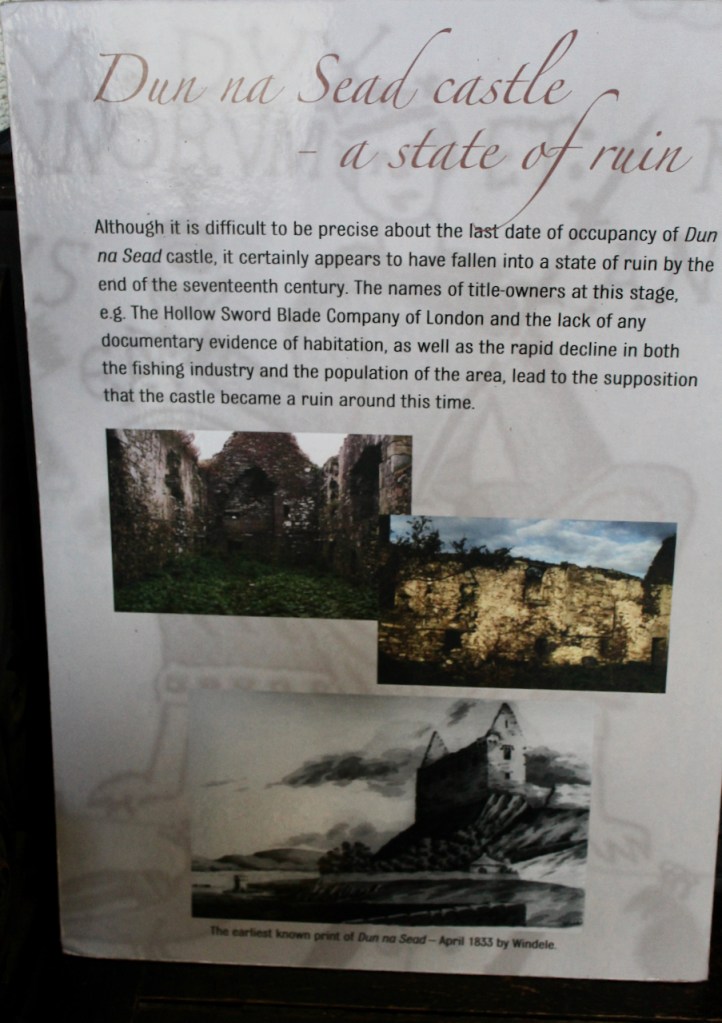

The website tells us that in the 1640s the castle was surrendered to Oliver Cromwell’s forces and passed to the Coppingers. In 1642 the O’Driscolls attempted to recover the castle by force. In the 1690s the Coppingers had to forfeit their property. After the 17th century the castle fell to ruin.

According to the information board in the castle, Percy Freke obtained the castle in 1703 from the investment company the Hollow Sword Blade Company. This company also owned Blarney Castle in County Cork for a period.

The Landed Estates database tells us:

“The Hollow Sword Blades Company was set up in England in 1691 to make sword blades. In 1703 the company purchased some of the Irish estates forfeited under the Williamite settlement in counties Mayo, Sligo, Galway, and Roscommon. They also bought the forfeited estates of the Earl of Clancarty in counties Cork and Kerry and of Sir Patrick Trant in counties Kerry, Limerick, Kildare, Dublin, King and Queen’s counties (Offaly and Laois). Further lands in counties Limerick, Tipperary, Cork and other counties, formerly the estate of James II were also purchased, also part of the estate of Lord Cahir in county Tipperary. In June 1703 the company bought a large estate in county Cork, confiscated from a number of attainted persons and other lands in counties Waterford and Clare. However within about 10 years the company had sold most of its Irish estates. Francis Edwards, a London merchant, was one of the main purchasers.” [7]

As well as her work on the Pirates of Baltimore, Bernie McCarthy has published a book about Baltimore Castle which we did not purchase, unfortunately. Called Baltimore Castle, An 800 Year History, I would love to read it, as I’d love to know more about how the McCarthys rebuilt the ruin. I will purchase a copy next time we are in the area!

Percy Freke’s son Ralph (1675-1718) gained the title of 1st Baronet Freke, of Rathbarry, County Cork. The property then passed to Ralph’s daughter Grace who married John Evans, and their son was John Evans-Freke (1743-1777), who became 1st Baronet Freke of Castle Freke, County Cork. He married Elizabeth Gore, daughter of Arthur Gore (1703-1773) 1st Earl of Arran, 3rd Baronet of Newtown, Viscount Sudley.

John and Elizabeth had a son named also named John Evans-Freke (1765-1845), who succeeded as 6th Baron Carbery. This John Evans-Freke married Catherine Charlotte Gore, daughter of Arthur Saunders Gore, 2nd Earl of Arran of the Arran Islands. John Evans-Freke was MP for Donegal from 1784-1790 and MP for Baltimore 1790-1800. He had Catherine Charlotte did not have surviving children and the title passed down to his nephew, son of his brother Percy Evans-Freke. I don’t think the castle was inhabited after Cromwell’s time, however. The 6th and 7th Barons of Carbery (George Patrick Percy Evans-Freke) did make some improvements to the town, Frank Keohane tells us.

Finally the castle was purchased by Patrick and Bernadette McCarthy, who restored it.

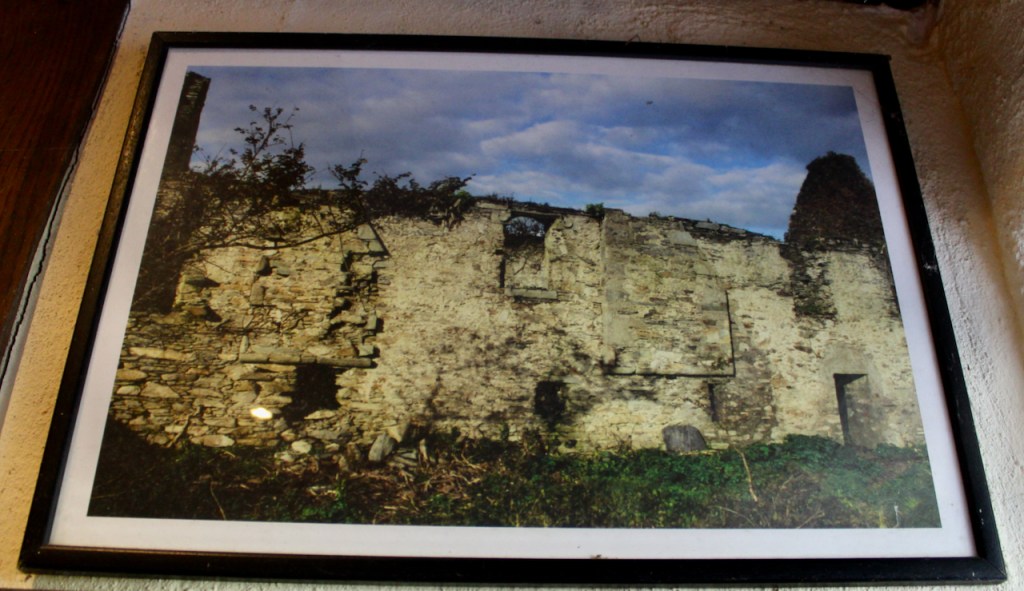

The castle was in a severely ruinous state when the McCarthys acquired it, as we can see from photographs in the noticeboards.

The castle now houses the museum and it contains wonderful artefacts and pieces of furniture. You can also go up to the ramparts and outside for beautiful views of the sea and of Baltimore.

Finally, I always assumed that Baltimore in Maryland was named after Baltimore in Cork. It turns out that this is not the case! It is indeed named after a Lord Baltimore who had ties with Ireland, but his title was for a property in County Longford!

© Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com

[1] p. 243. Keohane, Frank. The Buildings of Ireland. Cork City and County. Yale University Press: New Haven and London. 2020.

[2] p. 5, McCarthy, Bernie. Pirates of Baltimore from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century, Baltimore Castle Publications, 2012. Footnoted reference is to Timothy O’Neill, Merchants and Mariners in Medieval Ireland, p. 30.

[3] p. 23, McCarthy.

[4] p 29, McCarthy.

[5] p. 49, McCarthy.

[6] https://news.library.depaul.press/full-text/2009/04/22/pirates-and-st-vincent-de-paul-who-knew/

“Legend has it that from 1605 to 1607 when St. Vincent de Paul was a young priest he was captured by Algerian corsairs and sold to different masters before making a daring escape with one of his captors, a French renegade who wished to be reconciled with the Church. Although the account of Vincent’s captivity came from letters he wrote at the time to explain his two year disappearance, most historians today doubt the veracity of the account and speculate that the young Vincent had dropped out of sight because of his heavy debts, and the failure of his attempts to gain an ecclesiastical benefice. Nonetheless, the Vincentian (Lazarist) order also had missions in Algiers and Tunis to bring relief or freedom to captured Christians.

Fast fact: Between 1575 and 1869, there were 82 redemption missions where friars bought the freedom of an estimated 15,500 captives.“

3 thoughts on “Baltimore Castle (Dún Na Séad), Co. Cork P81 X968 – section 482”