Charleville Castle is not a Section 482 property, but sometimes opens to the public during Heritage Week, see the website.

http://www.charlevillecastle.ie/

It was built built 1798-1812 for Charles William Bury (1764-1835), later 1st Earl of Charleville, and was designed by Francis Johnston. The castle took 14 years to build, partly because Johnston was busy with other commissions as he was appointed to the Board of Works in 1805. From his work on the castle, Francis Johnston gained many more commissions, and he worked simultaneously on Killeen Castle in County Meath (1802-1812), Markree Castle in County Sligo (1802-1805, see my entry) and Glanmore, County Wicklow (1803-04).

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988, p. 82) that Charleville Castle is the “finest and most spectacular early nineteenth century castle in Ireland, Francis Johnston’s Gothic masterpiece, just as Townley Hall, County Louth, is his Classical masterpiece.” [1]

In Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life, Sean O’Reilly tells us that Charles William Bury and his wife, Catherine Maria née Dawson, had some hand in drawing plans for the building. He tells us: “Bury’s intention, as he wrote in his own unfinished account of the work, was to ‘exhibit specimens of Gothic architecture’ adapted to ‘chimneypieces, ceilings, windows, balustrades, etc.’ but without excluding ‘convenience and modern refinements in luxury.’ This recipe for the Georgian gothic villa had already been used at Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill in London, and Bury’s cultivated lifestyle in England certainly would have made him aware of that house and its long line of descendants.” [2]

Charles William Bury was President of the Royal Irish Academy between 1812 and 1822. He saw himself as the castle’s architect.

O’Reilly continues: “It may be that Bury himself – possibly with the assistance of his wife – outlined some of the more dramatic features in his new house, as is suggested by a number of drawings relating to the final design which still survive, now in the Irish Architectural Archive in Dublin. These all show the crude hand of an amateur, but equally betray a total freedom of imagination unshackled by the discipline of architectural training. In particular, a drawing of the exterior shows the smaller tower rising up out of the ground like a tree, with its base spreading and separating as it grows into the ground like roots.” [2]

Charleville Forest was written up by Mark Girouard for Country Life in 1962. Just over fifty-three years later Country Life published another article (October 2016), this time by Dr Judith Hill, awarded a doctorate for her work on the Gothic in Ireland.

Hill researched the role that Charles William Bury’s wife Catherine played in the design of Charleville, and shared her findings in a lecture given to the Offaly History Society and published on the Offaly History blog. She tells us:

“…it was time to look more closely at the collection of Charleville drawings which had been auctioned in the 1980s. Many of these are in the Irish architectural Archive, and those that were not bought were photographed. Here I found two pages of designs for windows that were signed by Catherine (‘CMC’: Catherine Maria Charleville). There is a sketch of a door annotated in her hand writing. There is a drawing showing a section through the castle depicting the wall decoration and furniture that had been attributed to Catherine. Rolf Loeber had a perspective drawing of the castle which showed the building, not quite as it was built, in a clearing in a wood. The architecture was quite confidently drawn and the trees were excellent. It was labelled ‘Countess Charleville’. I looked again at some of the sketches of early ideas for the castle in the Irish Architectural Archive. In one, the building design was hesitant while the trees were detailed; an architect wouldn’t bother with such good trees for an early design sketch. There was another that had an architect’s stamp; the massing of the building quickly drawn, the surrounding trees extremely shadowy. I could see Catherine and [Francis] Johnston talking about the design in these drawings.” [3]

Bence-Jones describes Charleville Forest castle as “a high square battlemented block with, at one corner, a heavily machicolated octagon tower, and at the other, a slender round tower rising to a height of 125 feet, which has been compared to a castellated lighthouse. From the centre of the block rises a tower-like lantern. The entrance door, and the window over it, are beneath a massive corbelled arch. The entire building is cut-stone, of beautiful quality.” [see 1]

Beginning in 1912, with the departure of Lady Emily, the last surviving daughter of the 4th Earl of Charleville, the house was left empty for 68 years.

In 1970 David Hutton-Bury (who owned and lived on the estate adjacent to the castle) granted a 35-year lease for the castle and surrounding 200 acres to Michael McMullen. McMullen lived in the castle and began its restoration in the early 1980s, during which time he restored the six main public rooms. In 1987 Bridget Vance and her mother, Constance Vance-Heavey, took over the leasehold from McMullen and continued the restoration. [4] It is now owned by the Charleville Castle Heritage Trust.

The land of Charleville Forest was inherited by Charles William’s father, John Bury (1725-1764) of Shannongrove, County Limerick. He succeeded to the estates of his maternal uncle, Charles Moore (1712-1764) 1st Earl of Charleville, in February 1764.

The oak forest and lands were gifted by Queen Elizabeth I to John Moore of Croghan Castle in 1577. Moore leased the land to Robert Forth, who built a house he called Redwood next to the river Clodiagh. In the 1740s Charles Moore 2nd Baron Moore and later 1st Earl of Charleville bought out the lease and made the house the family seat and named it Charleville, after himself.

Due to the lack of male heirs in the Moore family after Charles Moore’s death in 1764, and the fact that John Moore died later that year in 1764, the land was inherited by Charles William Bury who was the grand nephew of the last Earl, at just six months old.

Charles William Bury’s mother Catherine Sadleir was from Sopwell Hall County Tipperary. After her husband John Bury died, she married Henry Prittie (1743-1801) 1st Baron Dunally of Kilboy, which whom she went on to have several more children. The family probably moved to the house he had built called Kilboy House in County Tipperary.

On Charles Moore’s death the title became extinct until Charles William Bury was created 1st Earl of Charleville of the second creation in 1806. Before this, in 1797 he was created Baron Tullamore and in 1800, Viscount Charleville. Bury was returned to the Irish Parliament for Kilmallock in January 1790, but lost the seat in May of that year. He was once again elected for Kilmallock in 1792, and retained the seat until 1797. In 1801 he was elected as an Irish representative to sit in the British House of Lords in England.

Charles William Bury’s wife Catherine was daughter of Thomas Townley Dawson and widow of James Tisdall. From that marriage she had a daughter named Catherine.

Andrew Tierney describes Charleville Forest Castle in The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly:

“The castle comprises a tall castellated block of snecked [snecked masonry has a mixture of roughly squared stones of different sizes] limestone rubble with ashlar trim, with a great muscular octagonal tower to the northwest and a narrow round tower with soaring tourelle [small tower] to the NE…The composition breaks out more fully in the collective irregular massing of the towers, the chapel and the stable block, which rambles off to the west.” [7]

Tierney continues: “The positioning of a great window over the doorway bears comparison with the earlier group of Pale castles, such as Castle Browne (now Clongowes Woods school), attributed to Thomas Wogan Browne. It appears as a portcullis descending from a Gothic arch with a drawbridge in Lord Charleville’s original drawing (which also had a Radcliffean damsel in distress screaming from the battlements). He spent a lot of time drawing a sevenlight panelled window in its stead – the effect is much the same from afar – although the executed window is a more complex Perp design, probably by Johnston. The Tudor arch is employed three times in succession: over the door, in the recess of the great window and in the tripartite window above, which is subdivided into three further arches. This use of the same detailing at varying scales is also seen in the corbelling – a sort pair of intersecting hemispheres. The battlements are simple crenels on the main block but on the towers are rendered in a distinctly Irish fashion (a distinction Johnston would make at Tullynally and Markree), and here the corbelling is also more elaborate, sprouting upwards like cauliflower on the NE tower.“

To the right of the entrance front, and giving picturesque variety to the composition, is a long, low range of battlemented offices and a chapel, including a tower with pinnacles and a gateway.

The Stableyard lies beyond the chapel but is not open to the public, which is unfortunate as Tierney describes it as the finest castellated stableyard in Ireland, although now derelict. It is also by Francis Johnston.

Mark Bence-Jones continues:

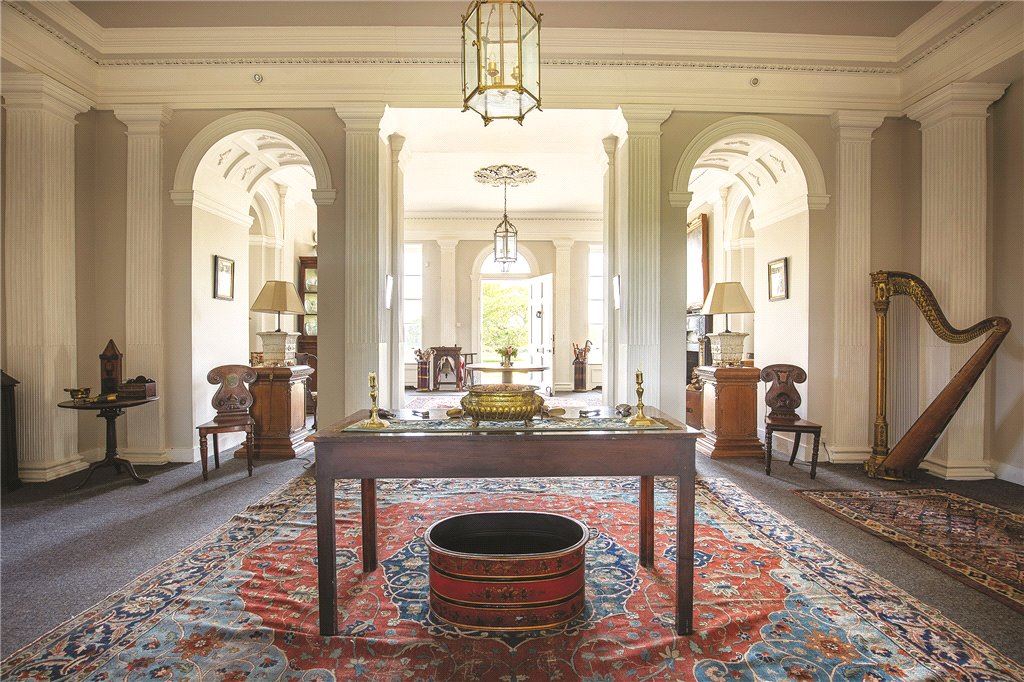

“The interior is as dramatic and well-finished as the exterior. In the hall, with its plaster groined ceiling carried on graceful shafts, a straight flight of stairs rises between galleries to piano nobile level, where a great double door, carved in florid Decorated style, leads to a vast saloon or gallery running the whole length of the garden front.”

The heavy oak stairs run from the basement to piano nobile. This imitates a similar configuration by James Wyatt at Fonthill and Windsor, which Lord Charleville knew. The upper stage, Tierney describes, has a plaster-panelled dado with ogee-headed niches in the style of Batty Langley, conceived for a parade of suits of armour in drawings by Lady Charleville.

Through the double doors is the most splendid room, the south facing Gallery. Unfortunately this was closed on our Heritage Week visit in 2024 due to filming of the Addams family movie, “Wednesday.” Mark Bence-Jones continues:“This is one of the most splendid Gothic Revival interiors in Ireland; it has a ceiling of plaster fan vaulting with a row of gigantic pendants down the middle; two lavishly carved fireplaces of grained wood, Gothic decoration in the frames of the windows opposite and Gothic bookcases and side-tables to match.“

The fan-vaulted ceiling is inspired by Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, which the Burys visited, which is in turn based on Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey, Tierney tells us. The ceiling is thought to have been executed by George Stapleton, who is also responsible for the fan-vaulting in Johnston’s Chapel Royal in Dublin Castle. The ceiling is anchored with clustered shafts along the walls, with bays framing the two Gothic chimneypieces, the doorcase on the north wall, and the Gothic casings of the windows.

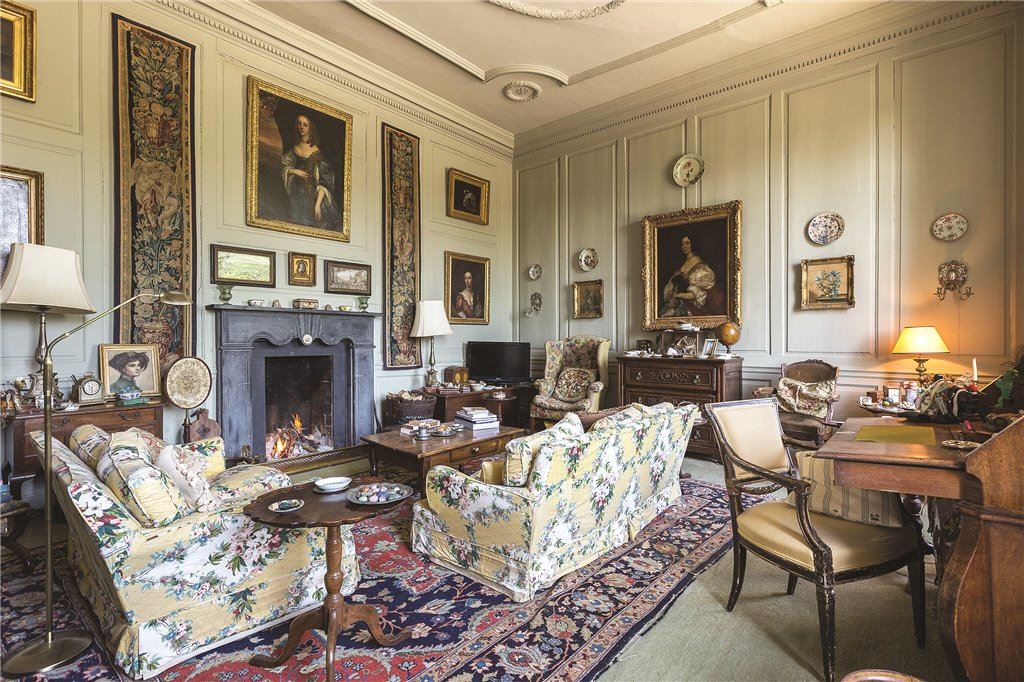

The drawing room and dining room are on either side of the entrance hall. The dining room on the west side has a coffered ceiling and a fireplace which is a copy of the west door of Magdalen College chapel, Oxford.

The dining room has, Tierney points out, a Dado of double-cusped panelling derived from the staircase balustrade of Strawberry Hill. The ceiling has crests of the family in the panel, supported by a Gothic frieze in the form of miniature fan vaults. The Moores are represented by a silhouette of a Moorish person, and the Burys by a boar’s head with an arrow through its neck. There are also “C”s for “Charleville.” The volunteers during Heritage Week told us that the ceiling is by William Morris, but Tierney tells us that he redecorated the room in 1875, but the scheme no longer survives. The decoration on the miniature fan vault frieze does look rather William Morris-esque to me, as well as the painting between the crests.

The Drawing Room is on the east side of the house. It has a fretwork ceiling with circular heraldic panels, a panelled dado and quatrefoil cornice. The room connects through a great arch with the rib-vaulted music room to its north. Unfortunately none of the furniture is original to the house but was brought it by the current owners.

The Music Room has a rib-vaulted ceiling.

The Music Room connects via a curved short corridor to the Boudoir in the northeast tower, a homage to Walpole’s Tribune in Strawberry Hill, Tierney tells us. This used to be my friend Howard Fox’s bedroom when he was staying as a guest, leading mushroom foraging walks in Charleville Woods! It is a star-vaulted circular room, with bays alternating between four wide round niches and smaller openings for windows, door and fireplace. Above was Lord Charleville’s dressing room, but we did not get to go there.

The stairs is tucked away in an odd place, behind a door off the northwest corner of the entrance hall. It is an intricate tightly curved staircase of Gothic joinery leading to the upper storeys, with Gothic mouldings on walls. The wall panelling is plaster painted and grained to look like oak. It rises through three storeys.

Tierney tells us that at the top of each flight, there is a great cavetto-moulded doorcase enriched with quatrefoil fretwork in plaster. The cavetto is a concave molding with a profile approximately a quarter-circle, quarter-ellipse, or similar curve. I find the staircase thrilling. Tierney writes: “Its dark colouring is in tune with the “gloomth” of its north facing aspect, and no Gothic room in Ireland rivals its Hmmer Horror atmosphere“!

A tragic accident occurred in 1861 when the 5th Earl’s young sister Harriet was sliding down the balustrade of the Gothic staircase from the nursery on the third floor and fell. She is said to haunt the staircase and to be heard singing.

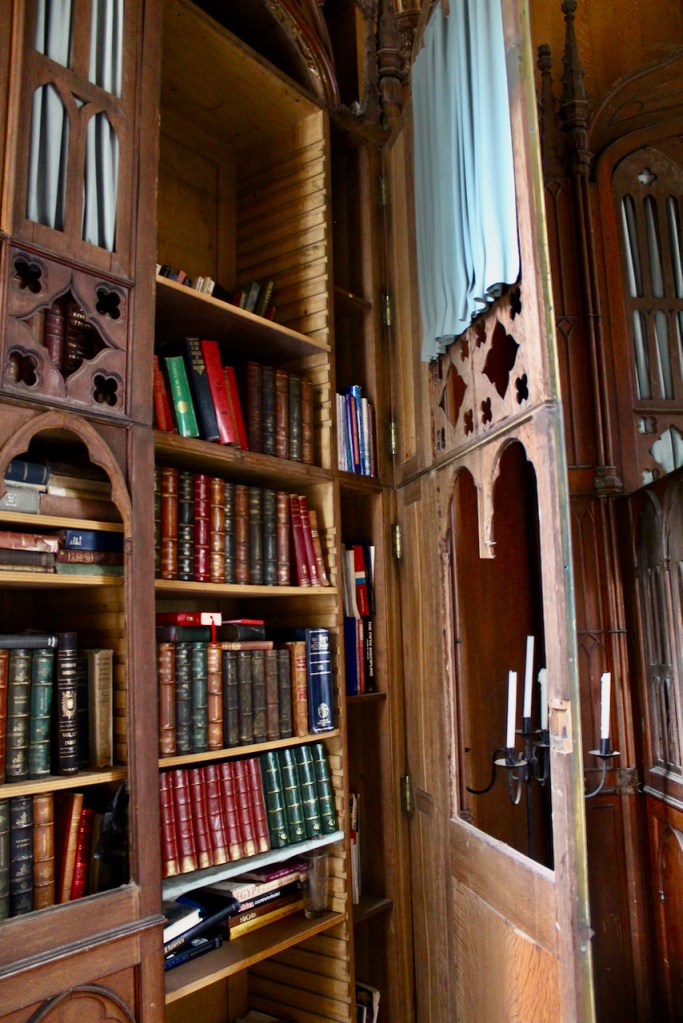

Beyond the staircase on the primary level is a small library with rib vaulted ceiling and Gothic bookcases.

The panelling by each bookcase can be opened to reveal more space, and behind one secret door is a small room which leads out to the chapel, the guide told us.

The library has stained glass Heraldic windows.

O’Reilly tells us: “Charleville Forest’s patron, Charles William Bury, from 1800 Viscount and from 1806 Earl of Charleville, was a man well versed in contemporary English taste and style. He inherited lands in Limerick, through his father’s maternal line, and in Offaly. His great wealth, lavish lifestyle and generous nature allowed him simultaneously to distribute largesse in Ireland, live grandly in London and travel widely on the continent…[p. 139] Charleville’s lack of success in his search for a sinecure proved ill for the future of the family fortunes for, continuing to live extravagantly above their means, they advanced speedily towards bankruptcy. On Charleville’s death in 1835, the estate was ‘embarrassed’ and by 1844, the Limerick estates had to be sold and the castle shut up, while his son and heir, ‘the greatest bore the world can produce’ according to one contemporary, retired to Berlin.“

The 2nd Earl held the office of Representative Peer [Ireland] between 1838 and 1851.

The 3rd Earl, Charles William George Bury (1822-1859), returned to the house in 1851, but with a much reduced fortune. He died young, at the age of 37, and his son, also named Charles William (1852-1874), succeeded as the 4th Earl at the age of just seven years old. His mother had died two years earlier. It seems that many of the Bury family were fated to die young.

The 4th Earl died at the age of 22 in 1874, unmarried, so the property passed to his uncle, Alfred, who succeeded as 5th Earl of Charleville but died the following year in 1875, without issue. The young 4th Earl had quarrelled with his sister who was next in line, so the property passed to a younger sister Emily.

In 1881 Emily married Kenneth Howard (1845-1885), son of the 16th Earl of Suffolk and of Louisa Petty-FitzMaurice, daughter of Henry Petty-FitzMaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne. On 14 December 1881 his name was legally changed to Kenneth Howard-Bury by Royal Licence, after his wife inherited the Charleville estate. He held the office of High Sheriff of King’s County in 1884.

After Emily’s death in 1931 the castle remained unoccupied. Her son Charles Kenneth Howard-Bury (1883-1963) preferred to live at another property he had inherited, Belvedere in County Westmeath (see my entry), which he inherited from Charles Brinsley Marlay. He auctioned the contents in 1948.

The house stood almost empty, with a caretaker, for years. When Charles Kenneth died in 1963, the property passed to a cousin, the grandson of the 3rd Earl’s sister with whom he had quarrelled. She had married Edmund Bacon Hutton and her grandson William Bacon Hutton legally changed his surname to Hutton-Bury when he inherited in 1964. The castle remained empty, until it was leased for 35 years to Michael McMullen in 1971. It had been badly vandalised at this stage. He immediately set to restore the castle.

More repairs were carried out by the next occupants, Bridget “Bonnie” Vance and her parents, who planned to run a B&B and wedding venue. Today the castle is run by Charleville Castle Heritage Trust.

For more information, see the website of the Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne, https://theirishaesthete.com/2019/10/14/charleville/

[1] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[2] p. 136. O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

[4] https://www.thedicamillo.com/house/charleville-castle-charleville-forest-charleville-forest-castle/

[5] https://www.archiseek.com/2010/1798-charleville-forest-tullamore-co-offaly/

[6] More photographs of Sopwell Hall:

[7] p. 232-8. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com

2 thoughts on “Charleville Forest Castle, Tullamore, County Offaly – sometimes open to public, run by Charleville Castle Heritage Trust”