On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

The five counties of Connacht are Galway, Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo.

As well as places to visit, I have listed separately places to stay, because some of them are worth visiting – you may be able to visit for afternoon tea or a meal.

For places to stay, I have made a rough estimate of prices at time of publication:

€ = up to approximately €150 per night for two people sharing (in yellow on map);

€€ – up to approx €250 per night for two;

€€€ – over €250 per night for two.

For a full listing of accommodation in big houses in Ireland, see my accommodation page: https://irishhistorichouses.com/accommodation/

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Galway

1. Ardamullivan Castle, Galway – national monument, to be open to public in future – check status

2. Athenry Castle, County Galway – open to public

3. Aughnanure Castle, County Galway (OPW)

4. Castle Ellen House, Athenry, Co. Galway – section 482

5. Coole Park, County Galway – house gone but stables visitor site open

6. Gleane Aoibheann, Clifden, Galway – gardens

7. Kylemore Abbey, County Galway

8. The Grammer School, College Road, Galway – section 482

9. Portumna Castle, County Galway (OPW)

10. Ross, Moycullen, Co Galway – gardens open

11. Signal Tower & Lighthouse, Eochaill, Inis Mór, Aran Islands, Co. Galway – section 482

12. Thoor Ballylee, County Galway

13. Woodville House Dovecote & Walls of Walled Garden, Craughwell, Co. Galway – section 482, garden only

Places to stay, County Galway

1. Abbeyglen Castle, Galway €€

2. Ardilaun House Hotel (formerly Glenarde), Co Galway – hotel €

3. Ashford Castle, Cong, Galway – hotel €€€

4. Ballindooly Castle, Co Galway – accommodation

5. Ballynahinch Castle, Connemara, Co. Galway – hotel €€€

6. Caherkinmonwee (or Caher) Castle, Co Galway – on airbnb, €€

7. Cashel House, Cashel, Connemara, Co Galway – hotel €€

8. Castle Hacket west wing, County Galway €

9. Claregalway Castle, Claregalway, Co. Galway – section 482 €€

10. Cregg Castle, Corrandulla, Co Galway – Airbnb €

11. Crocnaraw County House, Moyard, County Galway €

12. Currarevagh, Oughterard, Co Galway – country house hotel €€

13. Delphi Lodge, Leenane, Co Galway €€€

14. Emlaghmore Cottage, Connemara, County Galway €

15. Errisbeg House, Roundstone, County Galway

16. Glenlo Abbey, near Galway, Co Galway – accommodation

17. Kilcolgan Castle, Clarinbridge, Co Galway

18. Lisdonagh House, Caherlistrane, Co. Galway – section 482, see above

19. Lough Cutra Castle, County Galway, holiday cottages

20. Lough Ina Lodge Hotel, County Galway €

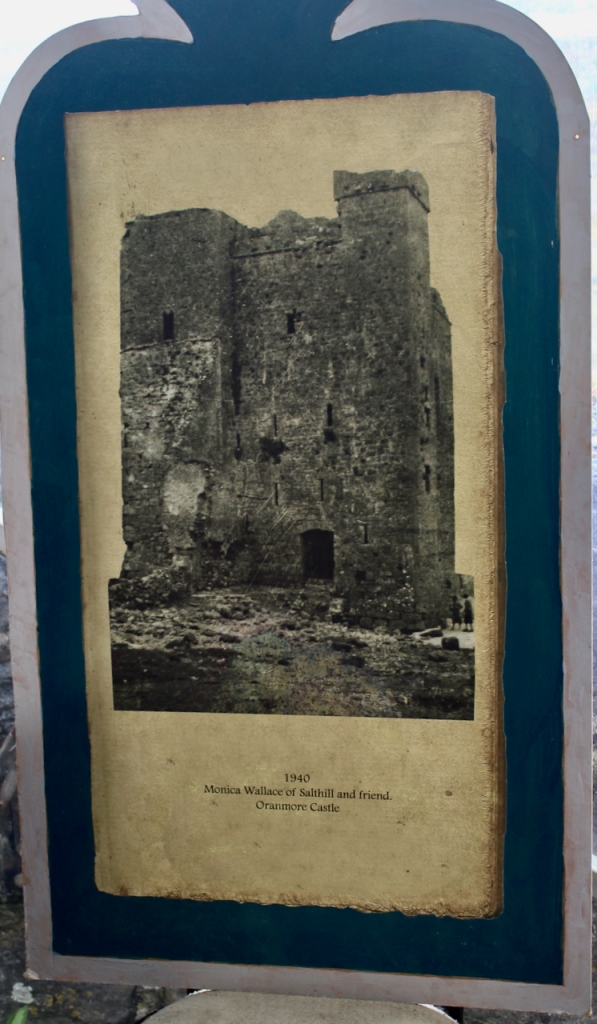

21. Oranmore Castle, County Galway – section 482 accommodation

22. Oranmore Lodge Hotel (previously Thorn Park), Oranmore, Co Galway

23. The Quay House, Clifden, Co Galway

24. Renvyle, Letterfrack, Co Galway – hotel

25. Rosleague Manor, Galway – accommodation €

26. Ross, Moycullen, Co Galway

27. Ross Lake House Hotel, Oughterard, County Galway

28. Screebe House, Camus Bay, County Galway €€€

Whole House Accommodation and Weddings, County Galway:

1. Carraigin Castle, County Galway – sleeps 10

2. Cloghan Castle, near Loughrea, County Galway – whole castle accommodation and weddings, €€€ for two.

Galway

1. Ardamullivan Castle, Galway – national monument, to be open to public in future – check status

“The castle is a is a restored six storey tower house. Part of the original defensive wall remains. Ardamullivan Castle was built in the 16th century by the O’Shaughnessy family. Although there is no history of the exact date of when the castle was built, it is believed it was built in the 16th century as it was first mentioned in 1567 due to the death of Sir Roger O’Shaughnessey who held the castle at the time.

“Sir Roger was succeeded by his brother Dermot, ‘the Swarthy’, known as ‘the Queen’s O’Shaughnessy’ due to his support shown to the Crown. Dermot became very unpopular among the public and even among his own family after he betrayed Dr Creagh, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh, who had sought refuge in the woods on O’Shaughnessy territory.

“Tensions came to a boil in 1579, when John, the nephew of Dermot, fought with Dermot outside the south gate of the castle in dispute over possession of the castle. Both men were killed in the fight. After this period the castle fell into ruin until the last century where it was restored to its former glory.” [1]

2. Athenry Castle, County Galway – open to public

see my OPW entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/14/office-of-public-works-properties-connacht/

3. Aughnanure Castle, County Galway (OPW)

see my OPW entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/14/office-of-public-works-properties-connacht/

4. Castle Ellen House, Athenry, Co. Galway, Eircode: H65 AX27 – section 482

http://www.castleellen.ie/

Open dates in 2025: Apr 6-9, 13-16, 20-23, 27-30, May 4-7, 11-14, 18-21, 25-28, June 1-4, 8-11, 15-18, 22-25, 29-30, July 1-2, Aug 16-24, 12 noon-4pm

Fee: adult €5, child/OAP/student free

5. Coole Park, County Galway – house gone but stables visitor site open

The website tells us:

“Coole Park, in the early 20th century, was the centre of the Irish Literary Revival. William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, John Millington Synge and Sean O’ Casey all came to experience its magic. They and many others carved their initials on the Autograph Tree, an old Copper beech still standing in the walled garden today.

“At that time it was home to Lady Gregory, dramatist and folklorist. She is perhaps best known as a co-founder of the Abbey Theatre with Edward Martyn of nearby Tullira Castle and Nobel prize-winning poet William Butler Yeats. The seven woods celebrated by W.B. Yeats are part of the many kilometres of nature trails taking in woods, river, turlough, bare limestone and Coole lake.

“At Coole, we invite you to investigate for yourself the magic and serenity of this unique landscape. Although the house no longer stands, you can still appreciate the environment that drew so many here. You will experience the natural world that Yeats captured in his poetry. Through this website, you can learn about this special place and its wildlife, as well as Gregory family history and literary connections.“

6. Gleane Aoibheann, Clifden, Galway – gardens

https://www.gardensofireland.org/directory/23/gleann+aoibheann/

The website tells us there are almost two hectares of seaside gardens dating back to the 1820s. One can also have tours of the house.

7. Kylemore Abbey, County Galway

https://www.kylemoreabbey.com/

The website tells us: “Nestled in the heart of Connemara, on the Wild Atlantic Way, Kylemore Abbey is a haven of history, beauty and serenity. Home to a Benedictine order of Nuns for the past 100 years, Kylemore Abbey welcomes visitors from all over the world each year to embrace the magic of the magnificent 1,000-acre estate.“

“Kylemore Castle was built in the late 1800s by Mitchell Henry MP, a wealthy businessman, and liberal politician. Inspired by his love for his wife Margaret, and his hopes for his beloved Ireland, Henry created an estate boasting ‘all the innovations of the modern age’. An enlightened landlord and vocal advocate of the Irish people, Henry poured his life’s energy into creating an estate that would showcase what could be achieved in the remote wilds of Connemara. Today Kylemore Abbey is owned and run by the Benedictine community who have been in residence here since 1920.

“Come to Kylemore and enjoy the new visitor experience in the Abbey, From Generation to Generation…..the story of Kylemore Abbey. Experience woodland and lakeshore walks, magnificent buildings and Ireland’s largest Walled Garden. Enjoy wholesome food and delicious home-baking in our Café or Garden Tea House. History talks take place three times a day in the Abbey and tours of the Walled Garden take place throughout the summer. Browse our Craft and Design Shop for unique gifts including Kylemore Abbey Pottery and award-winning chocolates handmade by the Benedictine nuns. Discover the beauty, history, and romance of Ireland’s most intriguing estate in the heart of the Connemara countryside.“

“Although Mitchell Henry was born in Manchester he proudly proclaimed that every drop of blood that ran in his veins was Irish. The son of a wealthy Manchester cotton merchant of Irish origin, Mitchell was a skilled pathologist and eye surgeon. In fact, before he was thirty years of age, he had a successful Harley Street practise and is known to have been one of the youngest ever speakers at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

“On his father’s death, Mitchell inherited a hugely successful family business and became one of the wealthiest young men in Britain at the time. Mitchell lost no time in quitting his medical career and turning instead to liberal politics where he felt he could change the world for the better. His newfound wealth allowed him to buy Kylemore Lodge and construct the castle and enabled him to bring change, employment, and economic growth to the Connemara region which was at the time stricken with hunger, disease, and desperation.

“On exiting the castle, turn around and look up, you will notice the beautiful carved angel which guards over it. In the hands of that angel is the coat of arms of Margaret Henry’s birth family, the Vaughan’s of County Down. Margaret’s arms over the front door proudly proclaim this as her castle. Look more closely and you will also see charming carvings of birds which were a favourite motif of the Henry’s. The birds represented the Henry’s hope that Kylemore would become the ‘nesting’ place of their family. Indeed, Kylemore did provide an idyllic retreat from the hustle and bustle of life in London where, even for the very wealthy, life was made difficult by the polluted atmosphere caused by the Industrial Age.

“At Kylemore Margaret, Mitchell and their large family revelled in the outdoor life of the ‘Connemara Highlands’. Margaret took on the role of the country lady and became much loved by the local tenants. Her passion for travel and eye for beauty were reflected in the sumptuous interiors where Italian and Irish craftsmen worked side by side to create the ‘family nest’. Sadly the idyllic life did not last long for the Henrys.

“In 1874 just a few years after the castle was completed, the Henry family departed Kylemore for a luxurious holiday in Egypt. Margaret was struck ill while travelling and despite all efforts, nothing could be done. After two weeks of suffering Margaret had died. She was 45 years old and her youngest daughter, Violet, was just two years of age. Mitchell was heartbroken. Margaret’s body was beautifully embalmed in Cairo before being returned to Kylemore. According to local lore Margaret lay in a glass coffin which was placed beneath the grand staircase in the front hall, where family and tenants alike could come to pay their respects. In an age when all funerals were held in the home, this is not as unusual as it may first seem. In time Margaret’s remains were placed in a modest red brick mausoleum in the woodlands of her beloved Kylemore.

“Although Henry remained on at Kylemore life for him there was never the same again. His older children helped him to manage the estate and care for the younger ones, as he attempted to continue his vision for improvements and hold on to his political career. By now he had become a prominent figure in Irish politics and was a founding member of Isaac Butt’s Home Rule movement. In 1878 work began on the neo-Gothic Church which was built as a beautiful and lasting testament to Henry’s love for his wife. Margaret’s remains were, for some reason, never moved to the vaults beneath the church and to this day she lays alongside Mitchell in the little Mausoleum nestled in the Kylemore woodlands.

“The Kylemore Estate, like the rest of Connemara, was made up of mountain, lakes and bog. In keeping with his policy of improvement and advancement, Henry began reclaiming bogland almost immediately and encouraged his tenants to do likewise. Forty years under the guiding hand of Mitchell Henry turned thousands of acres of waste land into the productive Kylemore Estate. He developed the Kylemore Estate as a commercial and political experiment and the result brought material and social benefits to the entire region and left a lasting impression on the landscape and in the memory of the local people. Mitchell Henry introduced many improvements for the locals who were recovering from the Great Irish Famine, providing work, shelter and later a school for his workers children. He represented Galway in the House of Commons for 14 years and put great passion and effort into rallying for a more proactive and compassionate approach to the “Irish problem”. Mitchell Henry gave the tenants at Kylemore a landlord hard to be equalled not just in Connemara but throughout Ireland.

“Despite the tragedies that befell the family and Mitchell’s hard work, life at Kylemore was certainly very luxurious. The castle itself was beautifully decorated and provided all that was needed for a family used to a lavish London lifestyle. The Walled Gardens provided a wide range of fruit and vegetables that included luxuries unthinkable to ordinary Irish people such as grapes, nectarines, melons and even bananas. Fruit and vegetable grown at Kylemore were often served at the Henry’s London dinner parties. Salmon caught in Kylemore’s lakes could also be wrapped in cabbage leaves and posted to London where they made a novel addition to the table. As well as a well-equipped kitchen, Kylemore also had several pantries, an ice house, fish and meat larder and a beer and wine cellar. The still room was used for a myriad of ingenious way to preserve and store food stuffs throughout the year.

“Guests at Kylemore were presented with a bouquet of violets to be worn at dinner. Violets were a craze in Victorian London as they represented loyalty and friendship. Kylemore castle was well equipped for entertaining and throughout the Salmon season from march to September the Henry’s welcomed many guests from Manchester and London. After dinner, entertainment was provided in the beautiful ballroom with its sprung oak floor for dancing with much of the music and plays being performed by the family themselves.

“The older Henry sons enjoyed such pastimes as photography and keeping exotic pets. Alexander Henry is responsible for many of the black and white photographs displayed at Kylemore today. His darkroom was located where Mitchell’s Café stands today. Lorenzo Henry kept a building called the ‘Powder House’ where he experimented with explosives. Indeed, Lorenzo had a brilliant mind like his father’s and went on to develop a number of successful inventions including the Henrite Cartridge for pigeon shooting. All of the family, including the girls enjoyed the outdoor life of fishing, shooting and horse riding. But the family were to suffer heartbreak again when Mitchell’s daughter Geraldine, was to be killed in a tragic carriage accident on the estate while out for a jaunt with her baby daughter and nurse. Both Geraldine’s daughter Elizabeth, and the baby’s nurse survived the accident but Geraldine’s death deeply affected the Henry Family and their connection to Kylemore.

“The Henry family eventually left Kylemore in 1902 when the estate was sold to the ninth Duke of Manchester. Mitchell Henry lived to be 84 years old but heartbreak had taken its toll and Mitchel died an aloof individual with a meagre sum of £700 in the bank.”

“In 1903, Mitchell Henry sold Kylemore Castle to the Duke of Manchester (William Angus Drogo Montague) and his Duchess of Manchester, Helena Zimmerman. They lived a lavish lifestyle financed by the Duchess’ wealthy father, the American businessman, Eugene Zimmerman.

“On arrival at Kylemore in Connemara the couple set about a major renovation, removing much of the Henry’s Italian inspired interiors and making the castle more suitable for the lavish entertainments that they hoped to stage in their new home, including an anticipated visit from their friend King Edward VII.

“The renovation included the removal of the beautiful German stained-glass window in the staircase hall and ripping out large quantities of Italian and Connemara marble. Local people were unhappy with the developments and felt the changes represented a desecration of the memory of the much-loved Margaret Henry and her beloved Kylemore Castle.

“Born in March 1877, William Montagu – the Duke was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, and succeeded his father when he was still a minor. The Duke inherited a grand estate which included lavish residences such as Tanderagee Castle in Co. Armagh and Kimbolton Castle in Huntington, England. However, his inheritance, which was administered by trustees was heavily indebted and together with his lavish lifestyle meant that by the age of 23 the Duke was bankrupt. When in 1900 the Duke married the Cincinatti born heiress, Helena Zimmerman, it seemed that his money problems could be forgotten. As Helena’s parents frowned on the relationship the couple eloped to Paris where they were married – a suitably glamorous start to the marriage of this sparkling and often talked about pair. It is thought that Helena’s father hoped the life of a country squire at Kylemore would help the Duke to leave behind his days of gambling and partying but this was not to be. The Duke and Duchess left Kylemore in 1914 following the death of Helena’s father. There were many stories in circulation which claimed that the Duke lost Kylemore in a late-night gambling session in the Castle however it seems more likely that following the death of Eugene Zimmerman there were insufficient funds available to the Duke to maintain the Kylemore estate.“

“Beginning in Brussels in 1598, following the suppression of religious houses in the British Isles when British Catholics left England and opened religious houses abroad, a number of monasteries originated from one Benedictine house in Brussels, founded by Lady Mary Percy. Houses founded from Lady Mary’s house in Brussels were at Cambray in France (now Stanbrook in England) and at Ghent (now Oulton Abbey) in Staffordshire. Ghent in turn founded several Benedictine Houses, one of which was at Ypres. Kylemore Abbey is the oldest of the Irish Benedictine Abbeys. The community of nuns, who have resided here since 1920, have a long history stretching back almost three hundred and forty years. Founded in Ypres, Belgium, in 1665, the house was formally made over to the Irish nation in 1682.The purpose of the abbey at Ypres was to provide an education and religious community for Irish women during times of persecution here in Ireland.

“Down through the centuries, Ypres Abbey attracted the daughters of the Irish nobility, both as students and postulants, and enjoyed the patronage of many influential Irish families living in exile.

“At the request of King James II the nuns moved to Dublin in 1688. However, they returned to Ypres following James’s defeat at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The community finally left Ypres after the Abbey was destroyed in the early days of World War One. The community first took refuge in England, and later in Co Wexford before eventually settling in Kylemore in December 1920.

“At Kylemore, the nuns reopened their international boarding school and established a day school for local girls. They also ran a farm and guesthouse; the guesthouse was closed after a devastating fire in 1959. In 2010, the Girl’s Boarding School was closed and the nuns have since been developing new education and retreat activities.“

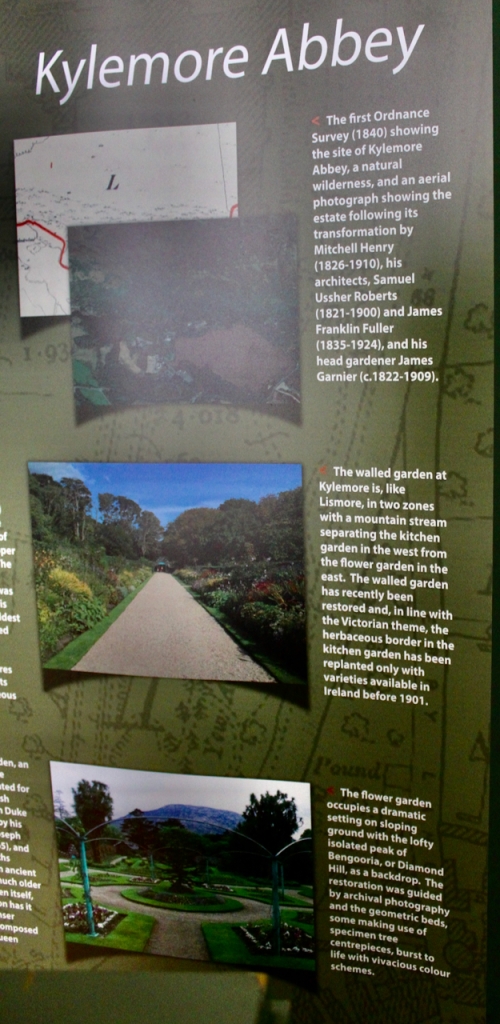

Display board from exhibition in the Irish Georgian Society, July 2022, The National Inventory of Architectural Heritage is compiling a Garden Survey.

“Kylemore Abbey’s Victorian Walled Garden is an oasis of ordered splendour in the wild Connemara Countryside. Developed along with the Castle in the late 1800s it once boasted 21 heated glasshouses and a workforce of 40 gardeners. One of the last walled gardens built during the Victorian period in Ireland it was so advanced for the time that it was compared in magnificence with Kew Gardens in London.

“Comprised of roughly 6 acres, the Garden is divided in two by a beautiful mountain stream. The eastern half includes the formal flower garden, glasshouses the head gardener’s house and the garden bothy. The western part of the garden includes the vegetable garden, herbaceous border, fruit trees, a rockery and herb garden. Leaving the Garden by the West Gate you can visit the plantation of young oak trees, waiting to be replanted around the estate. The Garden also contains a shaded fernery, an important feature of any Victorian Garden. Follow our self-guiding panels through the garden and learn more about its intriguing history and the extensive restoration work that it took to return the garden to its former glory after falling into disrepair.

“Today Kylemore is a Heritage Garden displaying only plant varieties from the Victorian era. The bedding is changed twice a year, for Spring and Summer and its colours change throughout the year. Be sure to visit us and fall in love with a garden that is surely the jewel in Connemara’s Crown.“

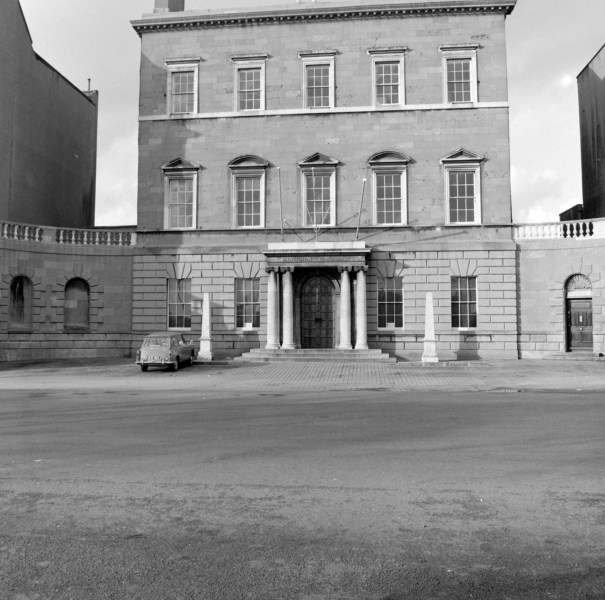

8. The Grammer School, College Road, Galway – section 482

www.yeatscollege.ie

Open dates in 2025: May 3-4, 10-11, 17-18, 24-25, June 7-8, July 1-31, Aug 1-12, 16-24, 9am-5pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student €5, child under 12 free

The National Inventory tells us about it under the heading of Yeats College. I am not sure why the Revenue section 482 spells is “Grammer” rather than “Grammar” but as it is listed as that every year, I defer to their spelling!

“Freestanding H-plan five-bay three-storey school with basement, built 1815, having slightly advanced gable-fronted end bays to front, and having recent addition to rear… Round-headed recesses to end bays and to ground floor of middle bays. Tripartite Diocletian windows to top floor of end bays, their recesses encompassing blind square-headed openings to first floor…Square-headed door opening to front within segmental-headed recess, having replacement timber panelled door within tooled limestone doorcase comprising moulded limestone surround surmounted by panelled blocks and moulded cornice framing paned overlight and flanked by paned timber sidelights with chamfered limestone surround.

“This large-scale former school retains its original character. Designed by Richard Morrison in 1807, the school was named after Erasmus Smith who founded the original grammar school, located at the courthouse, in 1699. The building displays a host of classical architectural features and a variety of window types. Its impressive scale on the main approach to the city from the east makes it one of the most significant buildings in the city.” [11]

9. Portumna Castle, County Galway (OPW)

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/05/02/portumna-castle-county-galway-an-office-of-public-works-property/

10. Ross, Moycullen, Co Galway – gardens open

This was the home of Violet Martin, one half of the Somerville and Ross partnership of writers, with Edith Somerville.

The website tells us of the house, which is open to accommodation:

“Ross Castle offers refined elegance for your special occasion or memorable holiday. The distinctive ambience of the Castle’s grand rooms and self catering cottages, accented with beautiful antique furnishings, will captivate you and up to 40 guests. This 120 acre estate is nestled in a picturesque setting of mountains, lake, and parkland.

“Constructed in 1539 by The “Ferocious” O’Flahertys, one of the most distinguished tribes of Galway, the property was later acquired by the Martin Family who built the present manor house upon the former castle’s foundation. After two fires and much neglect, the McLaughlin family acquired the property in the 1980s and have spent the past several decades restoring the estate to its present splendour.

“Upon entering the estate you are immediately awestruck by the grand front lawn; undulating to the lake and Parkland.

“From the Castle’s courtyard cottages and through the carriage entrance, a gothic archway entices you to explore the walled in Gardens.

“Stroll along the herbaceous bordered pathways while taking in the beauty and tranquility of your surroundings, shadowed by 6 massive yew trees hundreds of years old. Giant box hedges create unexpected surprises around every turn: stone sculptures, a red-brick pond, greenhouse, urns and statuary.“

11. Signal Tower & Lighthouse, Eochaill, Inis Mór, Aran Islands, Co. Galway – section 482

www.aranislands.ie

Open in 2025: April 1-October 31, 9am-5pm

Fee: adult €2.50, child €1.50, OAP/student free, family €5, group rates depending on numbers

12. Thoor Ballylee, County Galway

website: https://yeatsthoorballylee.org/home/

The website tells us:

“Thoor Ballylee is a fine and well-preserved fourteenth-century tower but its major significance is due to its close association with his fellow Nobel laureate for Literature, the poet W.B.Yeats. It was here the poet spent summers with his family and was inspired to write some of his finest poetry, making the tower his permanent symbol. Due to serious flood damage in the winter of 2009/10 the tower was closed for some years. A local group the Yeats Thoor Ballylee Society has come together and are actively seeking funds to ensure its permanent restoration. Because of an ongoing fundraising effort and extensive repair and restoration work, the tower and associated cottages can be viewed year round, and thanks to our volunteers are open for the summer months, complete with a new Yeats Thoor Ballylee exhibition for visitors to enjoy.“

13. Woodville House Dovecote & Walls of Walled Garden, Craughwell, Co. Galway – section 482, garden only

http://www.woodvillewalledgarden.com

Open dates in 2025: Feb 1-3, 7-10, 14-17, 21-24, 28, Mar 1-3, 7-10, 14-17, Apr 18-21, May 16-19, June 1-2, 6-9, 13-16, 20-23, 27-30, Aug 1-4, 8-11, 15-25, Feb-May, 12 noon-4pm, June and August, 11am-5pm, last entry 4.30pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP €9, student, €6, child €4 must be accompanied by adult, family €25 (2 adults and 2 children)

The website tells us Woodville is home to a restored walled kitchen garden along with a museum outlining the fascinating connection to Lady Augusta Gregory at Woodville. “Come for a visit to this romantic secret garden in the West of Ireland and enjoy the sights, scents and colours contained within the original stone walls.“

“The D’Arcy family most certainly have been at Woodville in 1750 when Francis D’Arcy left his initials on the keystone in the garden arch. The most famous member of the D’Arcy family to live at Woodville was Robert, who held the position of land agent to the estate of the first Marquis of Clanricarde for over 30 years – including the famine period. He does not seem to have been a popular figure in the local area, carrying out his duties with no small amount of vigour. After Robert’s death the estate passed to Francis Nicholas D’Arcy. He lived quietly at Woodville until his death in 1879.

“For the next 25 years little is known about Woodville. From the 1901 census we learn that Catherine Kelly was occupying the house and Lord Clanricarde was the landowner.

“On the 1st of May 1904 Henry Persse [1855-1928, brother of Augusta, who married William Henry Gregory of Coole Park] leased Woodville house and farm, which comprised of 460 acres, for a period of 29 years from the Marquise of Clanricarde. Henry Persse was the seventh son of Dudley Persse of Roxborogh, Kilchreest He was born on 14th of October 1855 and educated at Trinity College, Dublin. He went to India and served in the Indian police for some years, stationed at Madras. Coming into a legacy he returned to Ireland and married Eleanor Ada Beadon in 1888. They had two sons, Lovaine and Dermot, both born in Kilchreest.

“The grandparents of the present owners, Pat and Maria Donohue, took over the running of Woodville house and farm, and took a lease out on the farm in 1916 and purchased it outright in 1920. It is from the memories of their oldest daughter. Maureen Donohue, known as Sr. Austin of The Mercy Convent, Loughrea, that it was possible to collect information about what was grown in the walled garden at the time her parents came Maureen was just 3 years of age and her first memory as a child is of visiting the garden with her father and being given a lovely ripe peach picked from a tree by Harry Persse. There was an abundance of fruit trees of all different varieties at Wooville: peaches, pears, plums, greengage, damsons, cherries, quince, meddlers and apples, Cox’s Orange Pippins, Summers Eves, Brambly Seedlings, Beauty of Bath.

“Leading from the steps to the centre of the garden was an arch covered with climbing roses and in front of this were two bamboo trees on either side of the entrance. The central paths were lined with iron railings and box hedging. The garden was planted with poppies, lily of the valley, daffodils, snowdrops, and bluebells. It took four men to maintain the garden at Woodville and the head gardeners name was Tap Mannion and the cook in the house was Mary Lamb.Soft fruits included red and green gooseberries, Tay berries, loganberries, red and white currants and raspberries. There was also a fig tree in the south – east corner of the garden – demonstrating just what a microclimate the walls create.”

Places to stay, County Galway

1. Abbeyglen Castle, County Galway €€

The Visit Galway website tells us “Built in 1832 by John d’Arcy, Abbeyglen Castle was shortly after leased to the then parish priest, and was named ‘Glenowen House’.

“The castle was later purchased for use as a Protestant orphanage by the Irish Church Mission Society. Here girls would have been trained for domestic service. In 1953, the orphanage became a mixed orphanage until 1955, where it closed due to financial difficulties.

“The castle fell derelict and was home to livestock for some time. It was then purchased by Padraig Joyce of Clifden and became a hotel. The castle continued to operate as a hotel after the Hughes family took over in 1969 and still remains a prestigious hotel to this day.” [13]

2. Ardilaun House Hotel (formerly Glenarde), Co Galway – hotel €

https://www.theardilaunhotel.ie

The Landed Estates database tells us it was the town house of the Persse family, built in the mid 19th century, bought by the Bolands of Bolands biscuits in the 1920s and since the early 1960s has functioned as the Ardilaun House Hotel.

3. Ashford Castle, Cong, Galway/Mayo – hotel – see County Mayo. €€€

4. Ballindooly Castle, Co Galway – accommodation

https://www.visitgalway.ie/explore/heritage-and-history/castles/ballindooley-castle/

5. Ballynahinch Castle, Connemara, Co. Galway – hotel €€€

https://www.ballynahinch-castle.com

The website tells us:

“Welcome to Ballynahinch Castle Hotel, one of Ireland’s finest luxury castle hotels. Voted #6 Resort Hotel in in the UK & Ireland by Travel & Leisure and #3 in Ireland by the readers of Condé Nast magazine. Set in a private 700 acre estate of woodland, rivers and walks in the heart of Connemara, Co. Galway. This authentic and unpretentious Castle Hotel stands proudly overlooking its famous salmon fishery, with a backdrop of the beautiful 12 Bens Mountain range.

“During your stay relax in your beautifully appointed bedroom or suite with wonderful views, wake up to the sound of the river meandering past your window before enjoying breakfast in the elegant restaurant, which was voted the best in Ireland in April 2017 by Georgina Campbell.”

Mark Bence-Jones writes:

p. 25. “[Martin/IFR, Berridge/IFR] A long, many-windowed house built in late C18 by Richard Martin [1754-1834], who owned so much of Connemara that he could boast to George IV that he had “an approach from his gatehouse to his hall of thirty miles length” and who earned the nickname “Humanity Dick” for founding the RSPCA.

“When Maria Edgeworth came here 1833 the house had a “battlemented front” and “four pepperbox-looking towers stuck on at each corner”; but it seemed to her merely a “whitewashed dilapidated mansion with nothing of a castle about it.” The “pepperbox-looking towers” no longer exist; but both the front entrance and the 8 bay garden front have battlements, stepped gables, curvilinear dormers and hood mouldings; as does the end elevation.

“The principal rooms are low for their size. Entrance hall with mid-C19 plasterwork in ceiling. Staircase hall beyond; partly curving stair with balustrade of plain slender uprights. Long drawing room in garden front, oval of C18 plasterowrk foliage in ceiling, rather like the plasterwork at Castle Ffrench. Also reminiscent of Castle Ffrench are the elegant mouldings, with concave corners, in the panelling of the door and window recesses. The principal rooms still have their doors of “magnificently thick well-moulded mahogany” which Maria Edgeworth thought “gave an air at first sight of grandeur” though she complained that “not one of them would shut or keep open a single instant.” The drawing room now has a C19 chimneypiece of Connemara marble. The dining room has an unusually low fireplace, framed by a pair of Ionic half-columns. Humanity Dick was reknowned for his extravagant way of life, and in order to escape his creditors he retired to Bologne, where he died. He left the family estates heavily mortgaged, with the result that his granddaughter and eventual heiress, Mary Letitia Martin, known as “The Princess of Connemara” was utterly ruined after the Great Famine, when Ballynahinch and the rest of her property was sold by the Emcumbered Estates Court; she and her husband being obliged to emigrate to America, where she died in childbirth soon after her arrival Ballynahinch was bought by Richard Berridge, whose son sold it in 1925; after which it was acquired by the famous cricketer Maharaja Ranhisinhji, Jam Sahib of Nawanagar. It is now a hotel.”

6. Caherkinmonwee (or Caher) Castle, Co Galway – on airbnb, €€

The airbnb entry tells us: “A beautiful, original medieval castle experience can be yours for a weekend, a week, or even longer. You’ll be staying in the master bedroom, the highest room in the castle.

“This castle has been restored to its original state by using traditional materials, and also by using cutting edge technology. We used traditional local stone, limestone, as well as oak beams, to make the castle as traditional as possible, but it also has modern conveniences, such as solar water heating. The castle was built sometime in the 1400s but was refurbished in the last decade.“

A visit Galway website tells us it has been recorded that in 1574, the castle was held by Myler Henry Burke. The castle was left in ruin for over two hundred years before being purchased by Peter Hayes in 1996. Under the ownership of Mr. Hayes, the castle underwent a large restoration project. The castle still retains some of the original features such as bartizans on all four corners, a spiral staircase and latrines on the second, third, and fourth storey levels.

7. Cashel House, Cashel, Connemara, Co Galway – hotel €€

The website tells us: “A perfect start on your venture on the Wild Atlantic Way, Cashel House Hotel overlooks the majestic Cashel Bay on the west coast of Ireland. Here a traditional welcome awaits guests in this classic country house retreat. Built in the 19th century this gracious country home was converted to a family run four star hotel in 1968 by the McEvilly family. Situated in the heart of Connemara and nestling in the peaceful surroundings of 50 acres of gardens and woodland walks this little bit of paradise offers an ideal base from which to enjoy walking, beaches, sea and lake fishing, golf and horse riding.“

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

p. 293. “(Browne-Clayton/IFR) A house of ca 1850, asymmetrical gabled elevations, built by Captain [Thomas] Hazel [or Hazell] for his land agent, Geoffrey Emerson, [a great great grandfather of the current owner] who is said to have designed it. From 1921-52 the home of the O’Meara family who remodelled the interior with chimneypieces salvaged from Dublin and laid out most of the garden. In 1952 it became the house of Lt-Col and Mrs William Patrick Browne-Clayton, formerly of Browne’s Hill, who gave the garden its notable collection of fuschias. Cashels is now owned by Mr and Mrs Dermot McEvilly, who run it as a hotel.”

The website continues the history:

“From 1919 to 1951 Cashel House was the home of Jim O`Mara T.D. and his family. Jim O`Mara was the first official representative of Ireland in the United States and he devoted his life and talents to make Ireland a nation. Jim O`Mara was a keen botanist and found happiness in Cashel House.

“Over the years he carried out a lot of work on the Gardens. The three streams, which flow through the Garden, were a delight to him with their banks clothed with bog plants and Spirea & Osmunda ferns. O`Mara turned the orchard field into a walled garden of rare trees, Azaleas, Heather’s and dwarf Rhododendrons, which his children named ‘the Secret Garden’.

“In 1952 Cashel House became the home of Lt Col and Mrs Brown Clayton, formerly of Brownes Hill in Carlow. During their time at Cashel House the Browne Clayton’s had Harold McMillian, the late British Prime Minister, stay as their guest. The Browne Clayton’s also gave the Garden its notable collection of Fuchisas.

“Dermot and Kay McEvilly purchased Cashel House in 1967. Total refurbishment began immediately, with a fine collection of antiques being added and offering all modern facilities. The house reopened in May 1968 and ‘Cashel House Hotel’ was born.“

8. Castlehacket west wing, County Galway €

The entry tells us:

“CastleHacket House, steeped in Irish History. Built in 1703 by John Kirwan Mayor of Galway, the house is surrounded by nature and is very quiet and peaceful. Join in one of our “quiet “Yoga Classes, hike Connemara, stroll Knockma Woods, explore the lakes – world Famous for brown Trout fishing, or simply relax in the beautiful Park and Gardens.

“We are environmentally friendly and support green living, health and wellbeing.

“Ground Floor, West wing Guest Apartment in Historic CastleHacket House. Tastefully decorated, your own private door leads to 2 bedrooms, bathroom and kitchen-dining room. Tea and coffee facilities available and breakfast is included.

“Guest access to: Library, Reception/Lounge Room, Dining Room with tea and coffee facilaties, Sun Room, Outdoor Picnic area with bbq/pizza wood fired oven. Extensive gardens and woods. Safe car parking. Undercover area for Motorbikes and bicycles. Yoga classes and therapeutic Baths (extra cost). Wifi. Use of water hose, dry place to hang wet gear.“

Castlehacket takes its name from the Hackett family who owned the land prior to the Kirwans.

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988):

p. 70. “[Kirwan, sub Paley; Bernard, sub Bandon; Paley 1969] An early C18 centre block of 3 storeys over a basement, with 2 storey wings added later in C18, and a late C19 wing at the back. Burnt 1923; rebuilt 1928-9, without one of C18 wings and the top storey of the centre block. The seat of the Kirwans, inherited by Mrs. P.B. Bernard (nee Kirwan) 1875. Passed from Lt Gen Sir Denis Barnard 1956 to his nephew Percy Paley, who had a notable genealogical library here.”

The National Inventory describes it: “two-storey country house over basement, built c.1760 and rebuilt 1929 after being burnt in 1923. Eight-bay entrance front faces north onto large courtyard with gateway, has one-bay projections to each side of entrance bay, flat-roofed porch between projections, and two-bay east side elevation, and with slightly lower four-bay two-storey over basement service wing at west side and stables at east. Seven-bay garden front faces south, with pair of full-height canted bows on either side of central two bays, and is continued by slightly lower three-bay two-storey over basement block terminating in further rounded corner bay, to join with four-bay two-storey over basement service wing on west side of courtyard…Garden front has render frieze to parapet, with medallions separated by fluting…Porch has open arch to exterior, supported on columns with Temple of the Winds-style capitals, and approached by flight of steps. West bow of garden front has round-headed doorway with glazed timber door and fanlight and approached by three limestone steps. Garden to south of house bounded by low hedge, with parkland and sheep grazing beyond.

“This large country house displays mid-eighteenth-century, nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century work. The modestly presented front elevation is enhanced by the projecting bays and arched entrance. The brick bows to the garden elevation contrast nicely with the plain rendered walls elsewhere, and the decorated frieze and other details add interest and incident. The large lower block and service wing greatly enlarged the house and the fine accompanying stable block and demesne gateways provide a setting of considerable quality and interest.“

9. Claregalway Castle, Claregalway, Co. Galway H91 E9T3 – section 482 €€

www.claregalwaycastle.com

Open for accommodation: January 3-December 24

https://www.airbnb.ie/users/85042652/listings

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/04/20/claregalway-castle-claregalway-co-galway/

“Stay in one of our five beautiful rooms (Old Mill Rooms, Salmon Pool & Abbey Rooms). The River Room is situated beside the Castle on the banks of the River Clare in the village of Claregalway. Just 10km from Galway City Centre and within walking distance of a bus stop, restaurants/bars and the stunning Abbey. This family room is very comfortable with under-floor heating and luxurious bedding. Includes complimentary wine, tea/coffee & a generous continental breakfast.

“The space

“Claregalway Castle is a fully restored 15th century Anglo-Norman tower house and together with the castle grounds is a fabulous opportunity to savour the history while enjoying the comfort of your beautifully decorated and comfortable room.“

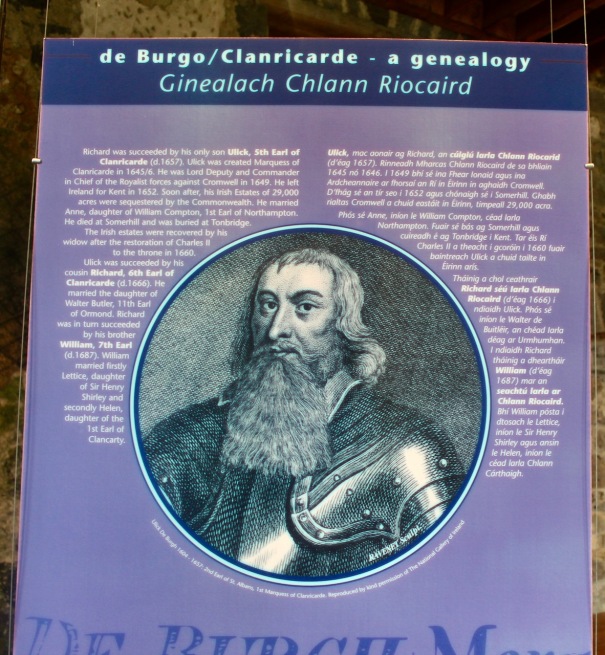

“Claregalway castle was the chief fortress of the powerful Clanricard de Burgo or Burke family from the early 1400s to the mid-1600s. The Clanricard Burkes were descended from William de Burgh, an English knight of Norman ancestry who led the colonial expansion into Connacht in the early 1200s. His brother Hubert was Justiciar of England. William became the progenitor of one of the most illustrious families in Ireland.“

The visit Galway website tells us: “Claregalway Castle was believed to have been built in the 1440’s as a stronghold to the De Burgo (Burke) family. The castle was strategically placed on a low crossing point of the Clare River, allowing the De Burgo family to control the water and land trade routes.

“In the past, the castle would have featured a high bawn/defensive wall, an imposing gate-house and a moat. The Battle of Knockdoe in 1504, was one of the largest pitched battles in Medieval Irish history, involving an estimated 10,000 combatants. On the eve of the battle, Ulick Finn Burke stayed at the Castle (which was 5km’s from the battle ground), drinking and playing cards with his troops. The Burke family lost the battle and the castle was later captured by the opponents, the Fitzgerald family.

“In the 1600’s, Ulick Burke, 5th Earl of Clanricarde [1st Marquess Clanricarde], held the castle however it was captured by Oliver Cromwell in 1651 who made the castle his headquarters. English military garrison occupied the castle in the early 1700’s and by the end of the 1700’s, the castle was described as going into decline and disrepair. During the War of Independence in 1919-21, the British once again used the castle as a garrison and a prison for I.R.A soldiers. In the later 1900’s, the famous actor Orson Welles is believed to have stayed at the castle as a 16 year old boy.

“Today, the castle has been fully restored to its former glory.” [6]

10. Cregg Castle, Corrandulla, Co Galway – Airbnb €

We were lucky to discover this wonderful castle for accommodation on airbnb. https://www.airbnb.ie/rooms/7479769?source_impression_id=p3_1652358063_y2E%2FxsRMKAae0vkr

The listing tells us that “Cregg Castle is a magical place built in 1648 by the Kirwin Family, one of the 12 tribes of Galway. It is set on 180 acres of pasture and beautiful woodlands. Your host, Artist Alan Murray who currently hosts the Gallery of Angels in the main rooms.“

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988):

p. 94. “A tower house built 1648 by a member of the Kirwan family [I think it was Patrick Kirwan (c. 1625-1679)]. And said to have been the last fortified dwelling to be built west of the Shannon; given sash-windows and otherwise altered in Georgian times, and enlarged with a wing on either side: that to the right being as high as the original building, and with a gable; that to the left being lower, and battlemented. In C18 it was the home of the great chemist and natural philosopher Richard Kirwan [1733-1812], whose laboratory, now roofless, still stands in the garden. It was acquired ca 1780 by James Blake [c. 1755-1818].”

Richard Kirwan married Anne Blake, daughter of Thomas (1701-1749), 7th Baronet Blake of Galway.

Mark Bence-Jones continues: “The hall, entered through a rusticated round-headed doorway with a perron and double steps, has a black marble chimneypiece with the Blake coat of arms. The dining room has a plasterwork ceiling. Sold 1947 by Mrs Christopher Kerins (nee Blake) to Mr and Mrs Alexander Johnston. Re-sold 1972 to Mr Martin Murray, owner of the Salthill Hotel, near Galway.”

Alan who now lives in the castle is, I believe, a nephew of Martin Murray of the Salthill Hotel.

The National Inventory describes it:

“multi-period house, comprising tower house of 1648 at centre, later modified and refenestrated to three-bay two-storey over half-basement, flanked to west by lower two-bay two-storey with attic over half-basement block of c.1780 with two-bay gable elevation, and to east by slightly lower three-bay three-storey over half-basement L-plan block of c. 1870 with gables over eastmost bay of front and rear elevations. Lower four-storey return block at right angles to rear of middle and west blocks, having two-bay elevations. Further two-bay single-storey block to rear of four-storey return, two-bay two-storey block to west of west block and with single-storey block further west again.“

11. Crocnaraw County House, Moyard, County Galway €

The website tells us:

“Crocnaraw Country House is an Irish Georgian Country Guest House (note we’re not a Hotel as such) by Ballinakill Bay,10 kilometres from Clifden, Connemara-on the Galway-Westport road.Set in 8 hectares of gardens and fields with fine views,Crocnaraw Country House has been winner of the National Guest House Gardens Competition for 4 years. This independently run Country Inn is noted for Irish hospitality and informality but without a sense of casualness.The House is tastefully and cheerfully decorated, each of its bedrooms being distinctively furnished to ensure the personal well-being of Guests. Fully licensed Crocnaraw Country House’s excellent cuisine is based on locally sourced fish and meat as well as eggs,fresh vegetables, salads and fruits from kitchen garden and orchard. Moyard is centrally located for Salmon and Trout fishing, deep-sea Angling, Championship Golf-Courses and many more recreational activities in the Clifden and Letterfrack Region of Connemara in County Galway.”

The National Inventory tells us that the house is a L-plan six-bay two-storey two-pile house, built c.1850, having crenellated full-height canted bay to south-east side elevation. Recent flat-roof two-storey extension to north-east…”Originally named Rockfield House, this building has undergone many alterations over time, the crenellated bay being an interesting addition. The area was leased by Thomas Butler as a Protestant orphanage and was known locally as ‘The Forty Boys’. The retention of timber sash windows enhances the building. The road entrance sets the house off plesantly.“

12. Currarevagh, Oughterard, Co Galway – country house hotel €€

The website tells us:

“Currarevagh House is a gracious early Victorian Country House, set in 180 acres of private parkland and woodland bordering on Lough Corrib. We offer an oasis of privacy for guests in an idyllic, undisturbed natural environment, providing exceptional personal service with a high standard of accommodation and old fashioned, traditional character. A genuine warm welcome from the owners.“

“Currarevagh House was built by the present owner’s great, great, great, great grandfather in 1842, however our history can be traced further back. The seat of the Hodgson Family in the 1600s was in Whitehaven, in the North of England, where they owned many mining interests. Towards the end of the 17th Century, Henry William Hodgson moved to Arklow and commenced mining for lead in Co Wicklow. A keen angler and shot he travelled much of Ireland to fulfil his sport (not too easy in those days), and during the course of a visit to the West of Ireland decided to prospect for copper. This he found along the Hill of Doon Road. At much the same time he discovered lead on the other side of Oughterard. So encouraged was he that he moved to Galway and bought Merlin Park (then a large house on the Eastern outskirts of Galway, now a Hospital) from the Blake family and commenced mining. As Galway was some distance from the mining activities he wanted a house closer to Oughterard. Currarevagh (not the present house, but an early 18th century house about 100m from the present house) was then owned by the O’Flaherties – the largest clan in Connaught – and, though no proof can be found, we believe that he purchased it from the O’Flaherties. However a more romantic story says he won it and 28,000 acres in a game of cards. The estate spread beyond Maam Cross in the heart of Connemara, and to beyond Maam Bridge in the North of Connemara. As the mining developed so the need for transportation of the ore became increasingly difficult until eventually two steamers (“the Lioness” and “the Tigress”) were bought. These, the first on Corrib, delivered the ore to Galway and returned with goods and passengers stopping at the piers of various villages on the way. All apparently went very well. The present house was built in 1842, suggesting a renewed wealth and success. No sooner however was present Currarevagh completed, then the 1850’s saw disaster. A combination of British export law changes, and vast seems of copper ore discovered in Spain and South America, heralded the end of mining activity in Ireland. The family, who were fairly substantial land owners at this stage, got involved in various projects, from fish farming to turf production – inventing the briquette in the process. Certainly Currarevagh was been run as a sporting lodge for paying guests by 1890 by my great grandfather; indeed we have a brochure dated 1900 with instructions from London Euston Railway Station. This we believe makes it the oldest in Ireland; certainly the oldest in continuous ownership. After the Irish Civil War of the 1920s the Free State was formed and many of the larger Estates were broken up for distribution amongst tenants. This included Currarevagh, even though they were not absentee landlords and had bought all their land in the first place. Landlords were assured they would be paid 5 shillings (approx 25c) an acre, however this redemption was never honoured, and effectively 10’s of thousands of acres were confiscated by the new state, leaving Currarevagh with no income, apart from the rare intrepid paying guest. At one stage a non local cell of the Free Staters (an early version of the IRA) tried to blow up Currarevagh, planting explosive under what is currently the dining room. However the plan was discovered before hand, and the explosive made safe. From then on a member of the local IRA cell remained at the gates of Currarevagh to warn off any of the marauding out of towners, saying Currarevagh was not to be touched. Evidently they were well integrated into the community, and indeed during the famine years it seems they did as much as they could to help alleviate local suffering. Indeed there is a famine graveyard on our estate; this was because the local people became too week to bring the dead to Oughterard. It is also one of the few burial grounds to contain a Protestant consecrated section. Having got through the 1920s and 30s, Currarevagh again got in financial trouble during the second world war: although paying guests did come to Ireland (mainly as rationing was not so strict here), the original house was put up for sale. It did not sell, and eventually was pulled down in 1946, leaving just Currarevagh House as it stands today. In 1947 it was the first country house to open as a restaurant to no staying guests; still, of course, the situation today.”

13. Delphi Lodge, Leenane, Co Galway €€€

and Boathouse cottages: https://hiddenireland.com/house-pages/boathouse-cottages/ €€

and Wren’s Cottage: https://hiddenireland.com/house-pages/wrens-cottage/ €€

The website tells us: “A delightful 1830s country house, fishing lodge and hotel in one of the most spectacular settings in Connemara Ireland. It offers charming accommodation, glorious scenery, great food and total tranquillity. Located in a wild and unspoilt valley of extraordinary beauty, the 1000-acre Delphi estate is one of Ireland’s hidden treasures…

“The Marquis of Sligo (Westport House) builds Delphi Lodge as a hunting/fishing lodge and is reputed to have named it “Delphi” based on the valley’s alleged similarity to the home of the Oracle in Greece.“

14. Emlaghmore Cottage, Connemara, County Galway €

https://hiddenireland.com/house-pages/emlaghmore-cottage/

“Connemara cottage, four hundred yards off the coast road, 10 km from Roundstone and 4 km from Ballyconneely.

“Emlaghmore Cottage was built in stone in about 1905, with just three rooms, and was extended in the 1960s to make a holiday home for a family. It stands on about ¾ acre running down to Maumeen lake, and is about 400 yards off the coast road (The Wild Atlantic Way) in a secluded situation with fine views. It has a shed with a supply of turf for the open fire in the living room, and garden furniture. There is a boat for anglers on the lake.“

15. Errisbeg House, Roundstone, County Galway

The home of Richard 7th Duke de Stacpoole, now a B&B https://errisbeghouse.ie/

16. Glenlo Abbey, near Galway, Co Galway – accommodation €€

https://www.glenloabbeyhotel.ie

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988): p. 138. “(Palmer, sub De Stacpoole/IFR) A long plain two storey house built onto slender tower with pointed openings near the top. The seat of the Palmer family.”

The estate belonged to the Ffrench family in the 1750s, an Anglo-Norman family. It was originally named Kentfield House, before becoming Glenlow or Glenlo, derived from the Irish Gleann Locha meaning “glen of the lake.” The adjacent abbey was built in the 1790s as a private church for the family but was never consecrated. In 1846 the house was put up for sale. It was purchased by the Blakes.

In 1897 it was purchased by the Palmers. In the 1980s it was sold to the Bourke family, who converted it to a hotel.

In 1990s two carriages from the Orient Express train were purchased and they form a unique restaurant.

17. Kilcolgan Castle, Clarinbridge, Co Galway €€€

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988):

p. 165. “(St. George, sub French/IFR; Blyth, B/PB; Ffrench, B/PB) A small early C19 castle, built ca 1801 by Christopher St. George, the builder of the nearby Tyrone House, who retired here with a “chere amie” having handed over Tyrone House to his son [Christopher St George was born Christopher French, adding St George to his surname to comply with his Great-Grandfather, George St George (c. 1658-1735) 1st Baron Saint George of Hatley Saint George in Counties Leitrim and Roscommon]. It consists of three storey square tower with battlements and crockets and a single-storey battlemented and buttressed range. The windows appear to have been subsequently altered. The castle served as a dower house for Tyrone, and was occupied by Miss Matilda St George after Tyrone was abandoned by the family 1905; it was sold after her death, 1925. Subsequent owners included Mr Martin Niland, TD; Mr Arthur Penberthy; Lord Blyth; and Mrs T.A.C.Agnew (sister of 7th and present Lord Ffrench); it is now owned by Mr John Maitland.”

18. Lisdonagh House, Caherlistrane, Co. Galway H91 PFW6 – section 482 – whole house rental and self-catering cottages.

www.lisdonagh.com

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: May 1-Oct 31st

Email: cooke@lisdonagh.com

The house is available as whole house rental, and it also has cottages for accommodation. See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/02/13/lisdonagh-house-caherlistrane-co-galway/

The website tells us:

“When looking for an authentic Irish country house to hire, the beautiful 18th century early Georgian Heritage home is the perfect choice. Lisdonagh House is large enough to accommodate families, friends and groups for private gatherings. This private manor house is available for exclusive hire when planning your next vacation or special event. Enchantingly elegant, Lisdonagh Manor House in Galway has been lovingly restored and boasts original features as well as an extensive antiques collection. Peacefully set in secluded woodland surrounded by green fields and magnificent private lake, this luxury rental in Galway is full of traditional character and charm. The tasteful decor pays homage to the history of Lisdonagh Manor with rich and warm colours in each room. The private estate in Galway is perfect for family holidays, celebrations and Board of Director strategy meetings. Lisdonagh is an excellent base for touring Galway, Mayo and the Wild Atlantic Way.“

It has two cottages, a coach house and gate lodge accommodation also.

19. Lough Cutra Castle, County Galway, holiday cottages

https://www.loughcutra.com/cormorant.html

info@loughcutra.com

“Nestled into the Northern corner of the courtyard, this beautifully appointed self catering cottage can sleep up to six guests – with private entrance and parking. Built during 1846 as part of a programme to provide famine relief during the Great Potato Famine of the time, it originally housed stabling for some of the many horses that were needed to run a large country estate such as Lough Cutra. In the 1920’s the Gough family, who were the then owners of the Estate, closed up the Castle and converted several areas of the courtyard including Cormorant into a large residence for themselves. They brought with them many original features from the Castle, such as wooden panelling and oak floorboards from the main Castle dining room and marble fireplaces from the bedrooms.

“We have furnished and decorated the home to provide a luxuriously comfortable and private stay to our guests. Each unique courtyard home combines the history and heritage of the estate and buildings with modern conveniences.“

The website gives us a detailed history of the castle:

“Lough Cutra Castle and Estate has a long and varied history, from famine relief to the billeting of soldiers, to a period as a convent and eventually life as a private home. It was designed by John Nash who worked on Buckingham Palace, and has been host to exclusive guests such as Irish President Michael D Higgins, His Royal Highness Prince Charles and Duchess of Cornwall Camilla, Bob Geldof, Lady Augusta Gregory and WB Yeats. The countryside surrounding Lough Cutra holds many a story, dating back centuries.“

“The extensive history of the Lough Cutra Castle and Estate can be traced back as far as 866 AD. It is quite likely that Ireland’s patron saint, Saint Patrick, passed Lough Cutra on his travels and also Saint Colman MacDuagh as he was a relative of nearby Gort’s King Guaire. The round tower Kilmacduagh built in his honour is an amazing site to visit near Lough Cutra. The countryside surrounding Lough Cutra holds stories for the centuries, all the way back to the Tuatha De Danann.

“The immediate grounds of the 600 acre estate are rich in remnants of churches, cells and monasteries due to the introduction of Christianity. A number of the islands on the lake contain the remnants of stone altars.

“The hillsides surrounding Lough Cutra contain evidence of the tribal struggle between the Firbolgs and the Tuatha De Danann (the Firbolgs and the Tuatha De Danann were tribes said to have existed in Ireland). These are from around the times of the Danish invasion. The ruined church of nearby Beagh on the North West shore was sacked by the Danes in 866 AD and war raged through the district for nearly 1000 years. In 1601 John O’Shaughnessy and Redmond Burke camped on the shores of the lake while they plundered the district.“

“In 1678, Sir Roger O’Shaughnessy inherited from Sir Dermot all the O’Shaughnessy’s Irish land – nearly 13,000 acres – and this included Gort and 2,000 acres around Lough Cutra and the lake itself. Following the revolution during which Sir Roger died of ill health, the Gort lands were seized and presented to Thomas Prendergast. This was one of the oldest families in Ireland. Sir Thomas came to Ireland on King William’s death in 1701 and lived in County Monaghan. The title to the lands was confused, but was in the process of being resolved when Sir Thomas was killed during the Spanish Wars in 1709. His widow, Lady Penelope decided to let the lands around the lake and the islands. On these islands, large numbers of apple, pear and cherry trees were planted, and some still survive today. The land struggle continued as the O’Shaughnessy’s tried to lay claim to the lands that had been taken from them by King William. In 1742 the government confirmed the Prendergast title, but it was not until 1753 that Roebuck O’Shaughnessy accepted a sum of money in return for giving up the claim.

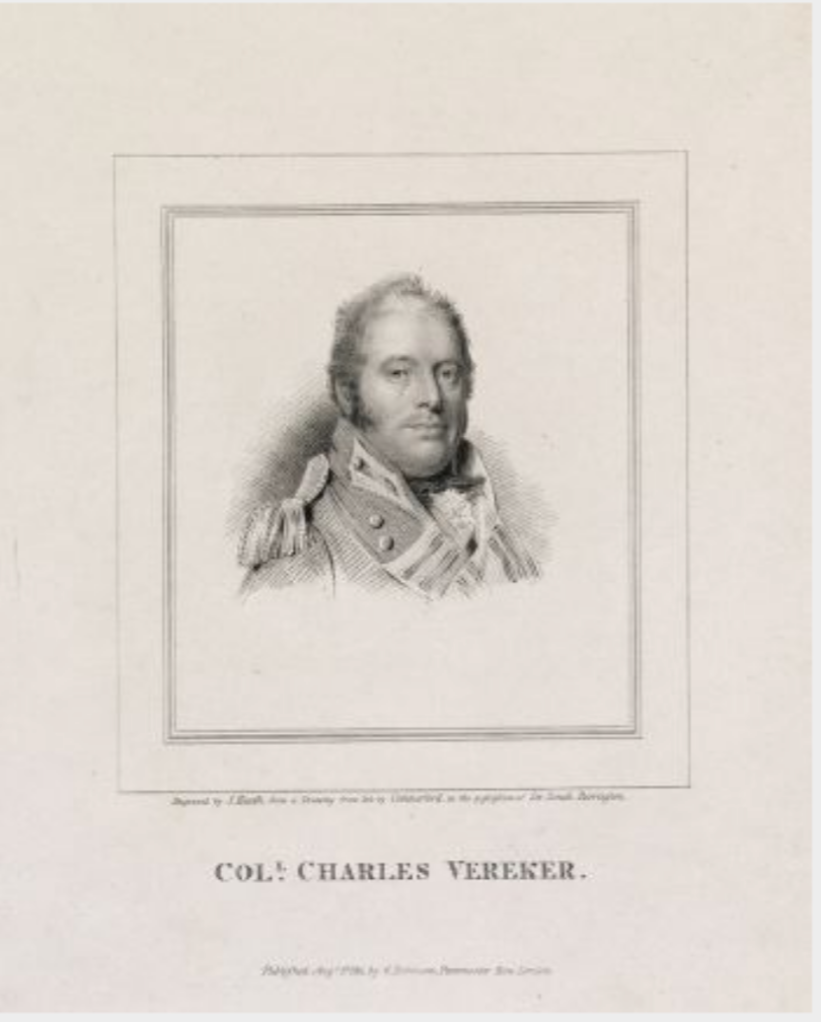

“Following Sir Thomas’s death, John Prendergast Smyth inherited the Gort Estate. It was John who created the roads and planted trees, particularly around the Punchbowl where the Gort River disappears on its way to Gort and Coole. John lived next to the river bridge in Gort when in the area. This area is now known as the Convent, Bank of Ireland and the old Glynn’s Hotel which is now a local restaurant. When John died in 1797 he was succeeded by his nephew, Colonel Charles Vereker who in 1816 became Viscount Gort. The estate at this time was around 12,000 acres.“

“When the estate was inherited by Colonel Vereker in 1797 he decided to employ the world renowned architect John Nash to design the Gothic Style building now known as Lough Cutra Castle. Colonel Vereker had visited Nash’s East Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight and was so taken with it that he commissioned the construction of a similar building on his lands on the shore of Lough Cutra. Nash also designed Mitchelstown Castle, Regents Park Crescent, his own East Cowes Castle, as well as being involved in the construction of Buckingham Palace.

“The Castle itself was built during the Gothic revival period and is idyllically situated overlooking the Estate’s 1000 acre lake. The building of the castle was overseen by the Pain brothers, who later designed and built the Gate House at Dromoland. The original building included 25 basement rooms and the cost of the building was estimated at 80,000 pounds. While the exact dates of construction are not known the building commenced around 1809 and went on for a number of years. We know that it had nearly been finished by 1817 due to a reference in a contemporary local paper.“

“The Viscount Gort was forced to sell the Castle and Estate in the Late 1840s having bankrupted himself as a result of creating famine relief. The Estate was purchased by General Sir William Gough, an eminent British General. The Gough’s set about refurbishing the Castle to their own taste and undertook further construction work adding large extensions to the original building, including a clock tower and servant quarters. Great attention was paid to the planting of trees, location of the deer park, and creation of new avenues. An American garden was created to the south west of the Castle. The entire building operations were completed in 1858 and 1859.

“A further extension, known as the Museum Wing, was built at the end of the nineteenth century to house the war spoils of General Sir William Gough by his Grandson. This was subsequently demolished in the 1950s and the cut stone taken to rebuild Bunratty Castle in County Clare.

“In the 1920s the family moved out of the Castle as they could not afford the running costs. Some of the stables in the Courtyards were converted into a residence for them. The Castle was effectively closed up for the next forty years, although during WWII the Irish army was billeted within the Castle and on the Estate.“

“The Estate changed hands several times between the 1930s and the 1960s when it was purchased by descendants of the First Viscount Gort. They took on the task of refurbishing the Castle during the late 1960s. Having completed the project, it was then bought by the present owner’s family.

“In more recent years there has begun another refurbishment programme to the Castle and the Estate generally. In 2003 a new roof was completed on the main body of the Castle, with some of the tower roofs also being refurbished. There has been much done also to the internal dressings of the Castle bringing the building up to a modern standard. Around the Estate there has been reconstruction and rebuilding works in the gate lodges and courtyards. There has also begun extensive works to some of the woodlands in order to try and retain the earlier character of the Estate.

“It is envisaged that more works will be undertaken over the coming years as the history and legend of Lough Cutra continues to build.“

20. Lough Inagh Lodge Hotel, County Galway €

https://www.loughinaghlodgehotel.ie/en/

“Lough Inagh Lodge was built on the shores of Lough Inagh in the 1880. It was part of the Martin Estate (Richard “Humanity Dick” Martin of Ballynahinch Castle) as one of its fishing lodges. It was later purchased by Richard Berridge, a London brewer who used the building as a fishing lodge in the 1880’s. It passed through the hands of the Tennent family, and then to Carroll Industries until 1989 it was redeveloped by the O’Connor family back to its former glory into a modern bespoke boutique lodge.”

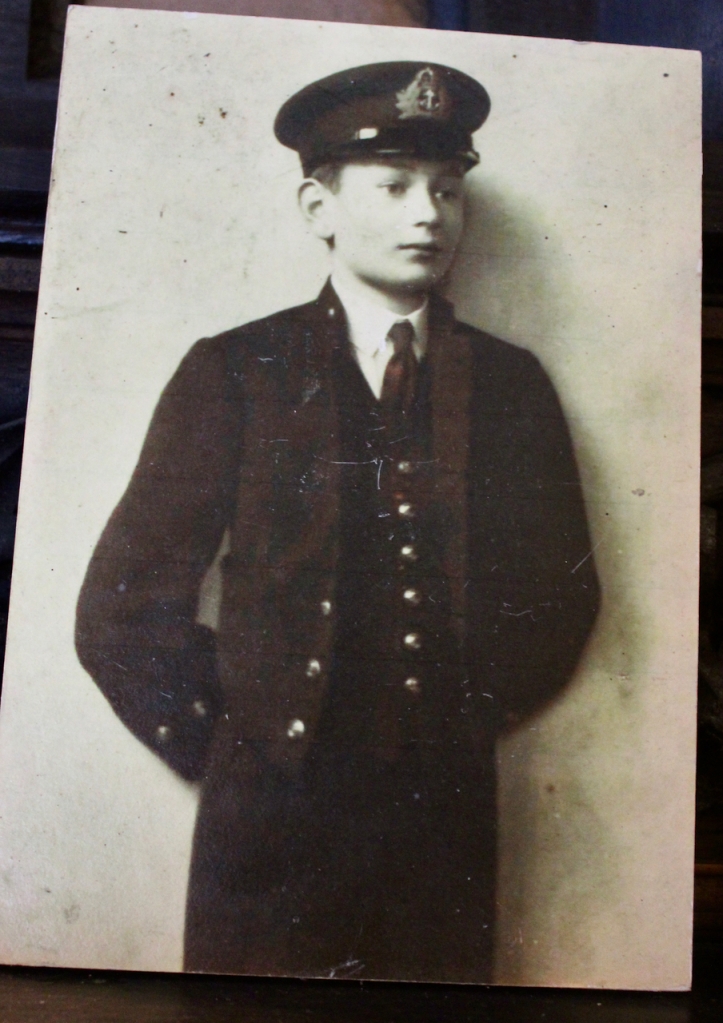

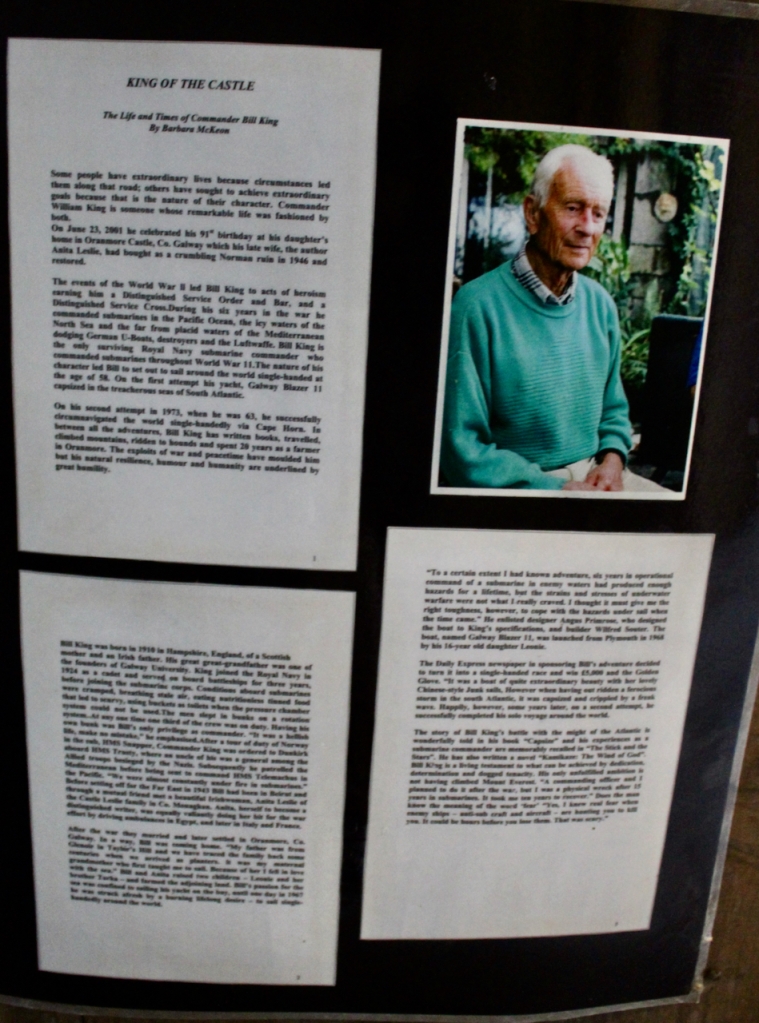

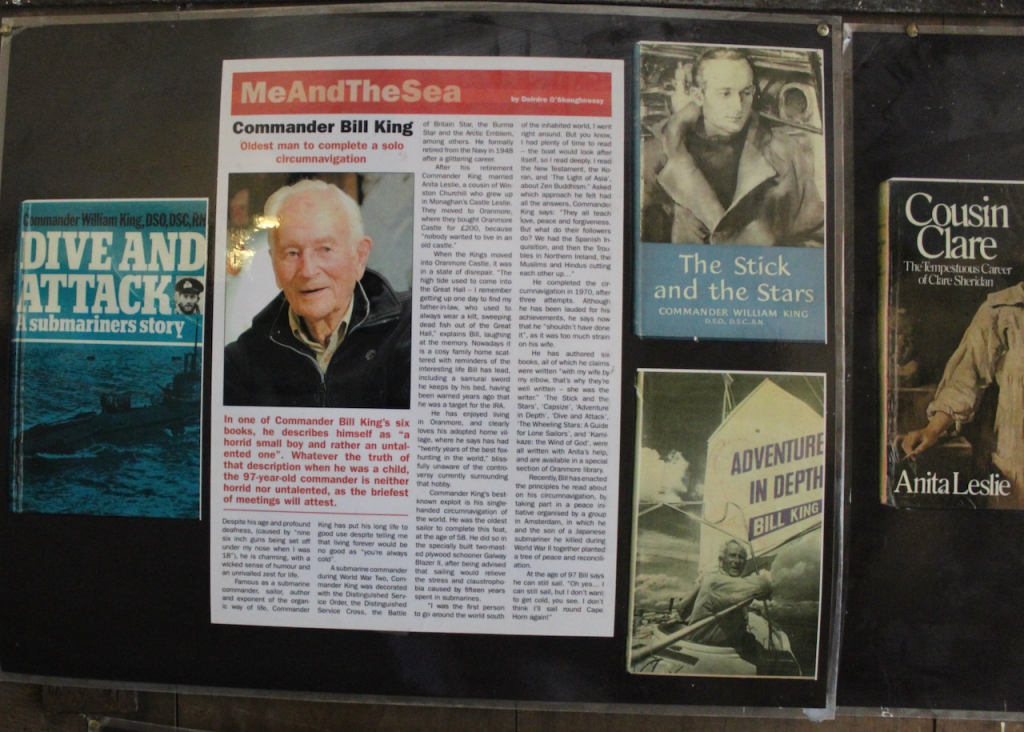

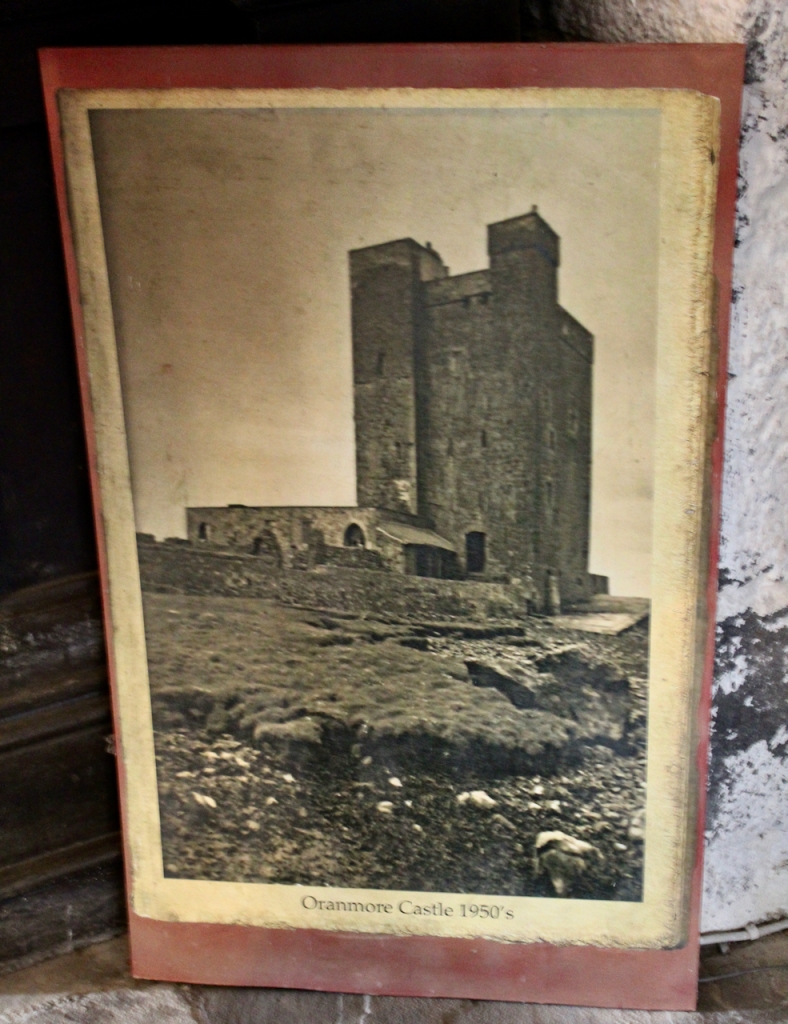

21. Oranmore Castle, County Galway, H91TFT6 – section 482 accommodation

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open dates for accommodation in 2025: May 1-October 31

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/04/13/oranmore-castle-oranmore-co-galway/

21. Oranmore Lodge Hotel (previously Thorn Park), Oranmore, Co Galway https://www.oranmorelodge.ie

“The Oranmore Lodge Hotel is a four-star family-run hotel that has earned the reputation of being a “home away from home”, situated in Oranmore, a popular village bursting with life and character. From the moment you arrive, take in the beautiful surroundings and unique character of the building that will encourage you to relax and leave it all behind. Guests have enjoyed our Irish hospitality for over 150 years.“

The National Inventory tells us:

“The Oranmore Lodge Hotel was formerly the residence of the Blake Butler family. The house was altered in the late nineteenth century and its name changed from Mount Vernon to Thornpark, and the steep gables, bay windows and crenellations are typical of that era. An interesting symmetrical elevation, enhanced by the family shield with motto. It retains much original fabric notwithstanding its extension on both sides.“

22. The Quay House, Clifden, Co Galway €€

The website tells us:

“Built for the Harbour Master nearly 200 years ago, The Quay House has been sensitively restored and now offers guest accommodation in fourteen bedrooms (all different) with full bathrooms – all but three overlook the Harbour. Family portraits, period furniture, cosy fires and a warm Irish welcome make for a unique atmosphere of comfort and fun.

“The owners, Paddy and Julia Foyle, are always on hand for advice on fishing, golfing, riding, walking, swimming, sailing, dining, etc – all close by.

“The Quay House is Clifden’s oldest building, dating from C1820. It was originally the Harbour Master’s house but later became a Franciscan monastery, then a convent and finally a hotel owned by the Pye family. Now providing Town House Accommodation in Clifen, it is run by the Foyle family, whose forebears have been entertaining guests in Connemara for nearly a century.

“The Quay House stands right on the harbour, just 7 minutes walk from Clifden town centre. All rooms are individually furnished with some good antiques and original paintings; several have working fireplaces. All have large bathrooms with tubs and showers and there is also one ground floor room for wheelchair users.“

23. Renvyle, Letterfrack, Co Galway – hotel

The website tells us: “First opened as a hotel in 1883, it is spectacularly located on a 150 acre estate on the shores of the Wild Atlantic Way in Connemara, Co. Galway. The grounds include a private freshwater lake for fishing and boating, a beach, woodlands, gardens and numerous activities on site including tennis, croquet, outdoor heated swimming pool, canoeing and shore angling. For a unique location, an award winning Restaurant, comfortable bedrooms and a truly uplifting break, here, the only stress is on relaxation.

“Its often-turbulent history has mirrored the change of circumstances and troubled history of Ireland, but it has been resilient and survived. Renvyle House was once home of the Chieftain and one of the oldest and most powerful Gaelic clans in Connacht; that of Donal O’Flaherty, who had a house on the site since the 12th Century where the hotel stands today.

“The Blakes (one of the 14 Tribes of Galway) bought 2,000 acres of confiscated O’Flaherty land in 1689. They leased it to the senior O’Flaherty family until the Blakes took up residence in 1822. Before then the ‘Big House’ was a thatched cabin 20ft by 60ft and one storey high. Henry Blake implemented major improvements to make it more compatible to a man of his means. The timber used in the building of the house extension was said to have been from a shipwreck in the bay. The thatch was replaced with slate roof and he added another storey. In 1825 the Blake family published the ‘Letters from the Irish Highlands’ describing the life and conditions in Connemara at that time. His widow, Caroline Johanna opened it first as a hotel in 1883. ‘Through Connemara in a Governess Cart’ published in 1893, written by Edith Somerville and Violet Martin. In this beautifully illustrated book, they visit Ballynahinch Castle, Kylemore Abbey and Renvyle House.“

“The house was sold before the War of Independence In 1917 to surgeon, statesman and poet Oliver St.John Gogarty played host to countless distinguished friends including Augustus John, W.B. Yeats (who came on his honeymoon to Renvyle House and Yeat’s first Noh play was first performed in the Long Lounge). Indeed in 1928 Gogarty had a flying visit from aviator Lady Mary Heath and her husband which was well documented. The House was burned to the ground during the Irish Civil War in 1923 by the IRA, as were many other home of government supporters; along with Gogarty’s priceless library. The house was rebuilt by Gogarty as a hotel in the late 1920’s in the Arts & Crafts design of that era.

“My house..stands on a lake, but it stands also on the sea – waterlilies meet the golden seaweed…at this, the world’s end” Oliver St. John Gogarty.

“The war years were difficult times although the hotel stayed open all year round. Dr. Donny Coyle visited Renvyle house in July 1944 with friends and as fate would have it, he bought it with friends Mr. John Allen and Mr. Michael O’Malley in 1952 from the Gogarty estate and they reopened it on the 4th July that year.

“The 1958 brochure announced new facilities in the hotel bedrooms. “Shoe cleaning. Shoe polishing and shining materials are in each room, just lift the lid of the wooden shoe rest.” Guests were also informed that dinner was served from 7.30pm to 9pm, and that they were not to go hungry through politeness. “Don’t be shy, if you’d like a little more, please ask.” – and that ethos of hospitality remains to this day.

“It remains in the Coyle family to this day, owned by Donny’s son John Coyle and his wife Sally.Their eldest daughter Zoë Fitzgerald is also involved with the hotel, is the Marketing Director and Chairman of the Board.“

24. Rosleague Manor, Galway – accommodation €€

The website tells us: “Resting on the quiet shores of Ballinakill Bay, and beautifully secluded within 30 acres of its own private woodland, Rosleague Manor in Connemara is one of Ireland’s finest regency hotels.“

The National Inventory tells us: “Attached L-plan three-bay two-storey house, built c.1830, facing north-east and having gabled two-storey block to rear and multiple recent additions to rear built 1950-2000, now in use as hotel…This house is notable for its margined timber sash windows and timber porch. The various additions have been built in a sympathetic fashion with many features echoing the historic models present in the original house.”

25. Ross, Moycullen, Co Galway – see above

26. Ross Lake House Hotel, Oughterard, County Galway

“Ross Lake House Hotel in Galway is a splendid 19th Century Georgian House. Built in 1850, this charming Galway hotel is formerly an estate house of the landed gentry, who prized it for its serenity. Set amidst rambling woods and rolling lawns, it is truly a haven of peace and tranquillity. Echoes of gracious living are carried throughout the house from the elegant drawing room to the cosy library bar and intimate dining room.“

27. Screebe House, Camus Bay, County Galway €€€

“Tucked away in the idyllic surrounds of Camus Bay, experience the best of Connemara at one of Ireland’s finest Victorian country homes, Screebe House.

“Built in 1872 as a fishing lodge and lovingly restored by the Burkart family in 2010, Screebe House offers guests an experience of luxury comfort, and effortless charm. With open fireplaces, high ceilings and heritage décor, Screebe’s elegant spaces evoke a sense of grandeur and provide the perfect setting to read a good book or savour a delicious glass of wine while taking in the breathtaking Connemara scenery.

“Screebe, originating from the Irish word ‘scribe’ meaning destination, is ideally located for those who want to explore the stunning scenery of Connemara or partake in a wealth of activities available, from renting bikes to fishing, deer spotting, swimming, hiking, and more. Screebe’s privately owned estate extends 45,000 acres, one of the largest estates in the country.“

Whole House Accommodation and Weddings, County Galway:

1. Carraigin Castle, County Galway – sleeps 10

The website tells us:

“Surrounded by seven acres of lawns, park and woodland, Carraigin Castle is an idyllic holiday home in a beautiful setting on the shores of Lough Corrib, one of Ireland’s biggest lakes, famous for its brown trout and its multitude of picturesque islands. From the Castle one can enjoy boating and fishing on the lake, walking, riding and sightseeing all over Galway and Mayo, or just relax by the open hearth and contemplate the charm and simple grandeur of this ancient dwelling, a rare and beautiful example of a fortified, medieval “hall house”.

“Family groups or close friends will love the relaxed atmosphere of this authentic 13th-century manor house, which has been restored by the present owner after languishing for more than two centuries as a crumbling, roofless ruin. Carraigin’s church-like structure sits on a rise reached by an avenue across the tree-lined Pleasure Ground.“

The History:

“Despite its massive, castellated walls, Carraigin was never a mere fortress, but rather, an elegant home where a land-owning family could live securely in turbulent times. For some ten generations, the castle housed the descendants of its founder, Adam Gaynard III, grandson of a Norman adventurer who had taken part in the colonisation of the neighbourhood by the great de Burgo conquerors in 1238.

“Towards 1650, another military adventurer, George Staunton, acquired “the castle and lands of Cargin”, which his descendants continued to own until 1946. By, then, the castle had long been

abandoned. Stripped of its roof in the early 18th century, Carraigin’s relatively recent upper storeys and finer stonework were demolished and burned to make lime for the construction of the nearby Georgian mansion which replaced it.

“However, the solid masonry core of the original 13th Century building had been constructed with such skill that it weathered centuries of neglect, surviving as a romantic, ivy-covered ruin until, in 1970, the castle was restored to its original form and purpose.“

The Interior: “The ancient-looking, nail-studded front door on the ground floor, often mistaken for an authentic antiquity, was actually made by the owner during the building’s restoration in the 1970s. Round the corner, an imposing stone staircase leads to another grand entrance, into the lofty, oak-beamed Great Hall featuring a wide, stone-arched fireplace that provides a comforting aroma of turf and wood-smoke.