On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Places to visit in County Meath

1. Beauparc House, Navan, Co. Meath, C15 D2K6 – section 482

2. Dunsany Castle, Dunsany, Co. Meath – section 482

3. Gravelmount House, Castletown, Kilpatrick, Navan, Co. Meath – section 482

4. Hamwood House, Dunboyne, Co. Meath – section 482

5. Loughcrew House, Loughcrew, Old Castle, Co. Meath – section 482

6. Moyglare House, Moyglare, Co. Meath – section 482

7. Oldbridge House, County Meath – Battle of the Boyne Museum – OPW

8. Slane Castle, Slane, Co. Meath – see website for tours

9. St. Mary’s Abbey, High Street, Trim, Co. Meath – section 482

10. Swainstown House, Kilmessan, Co. Meath, C15 Y60F – section 482

11. Tankardstown House, Rathkenny, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 D535 – section 482

12. Trim Castle, County Meath – OPW

Places to stay, County Meath:

1. Bellinter House near Bective, County Meath – hotel and restaurant

2. Boyne House Slane (formerly Cillghrian Glebe), Chapel Street, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 P657 – section 482 accommodation

3. Clonleason Gate Lodge, Fordstown, County Meath

4. Dunboyne Castle, County Meath

5. Highfield House, Trim, County Meath

6. Johnstown Estate, Enfield, Co Meath – hotel

7. Killeen Mill, Clavinstown, Drumree, Co. Meath – section 482 accommodation

8. Moyglare House, Moyglare, Co. Meath – section 482

9. Rockfield House Courtyard Apartment, Kells, County Meath

10. Rosnaree, Slane, Co Meath – accommodation

11. Ross Castle, Mountnugent, County Meath whole castle or self-catering accommodation

12. Slane Castle, County Meath C15 XP83

13. Tankardstown House, Rathkenny, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 D535 – section 482

Whole house booking/wedding venues, County Meath

1. Ballinlough Castle, County Meath – group castle accommodation, wedding venue

2. Boyne Hill estate, Navan, County Meath – whole house rental

3. Clonabreany House, County Meath wedding venue

4. Durhamstown Castle, Bohermeen, County Meath – whole house rental

5. Loughcrew House, Loughcrew, Old Castle, Co. Meath – section 482 whole house accommodation

6. Mill House, Slan, County Meathe – weddings

7. Rockfield House, Kells, County Meath

8. Ross Castle, Mountnugent, County Meath whole castle or self-catering accommodation

9. Slane Castle, County Meath C15 XP83

Places to visit:

1. Beauparc House, Navan, Co. Meath C15 D2K6 – section 482

Open dates in 2026: May 1-31, June 1-5, 8-12, 15-19, 22-26, Aug 15-23, 11am -3pm,

Fee: adult €14, OAP/student €12.50, child €8.40

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/07/22/beauparc-house-beau-parc-navan-co-meath/

2. Dunsany Castle, Dunsany, Co. Meath C15 XR80 – section 482

Open dates in 2026: June 20 -30, July 1-31, Aug 1-23, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €25, OAP €20, student €15, child 13 years and over €15, child under 12 years free

3. Gravelmount House, Castletown, Kilpatrick, Navan, Co. Meath – section 482

Open dates in 2026: Jan 2-12, May 1-30, June 1, Aug 15-23, Nov 16-20, 30, Dec 1-4, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student/child €5

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/06/13/gravelmount-house-castletown-kilpatrick-navan-co-meath/

4. Hamwood House, Dunboyne, Co. Meath A86 C667 – section 482

Open dates in 2026: Feb 4-8, 11-15, 18-22, 25-28, Mar 1, 11am-1pm & 3pm-5pm, May 6-10,15-17, June 4-7,11-14, July 2-5,11-12, 16-19, August 2-5,9-12,15-23, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student €20, child under 10 years free

We visited in November 2022 – https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/08/03/hamwood-house-dunboyne-co-meath/

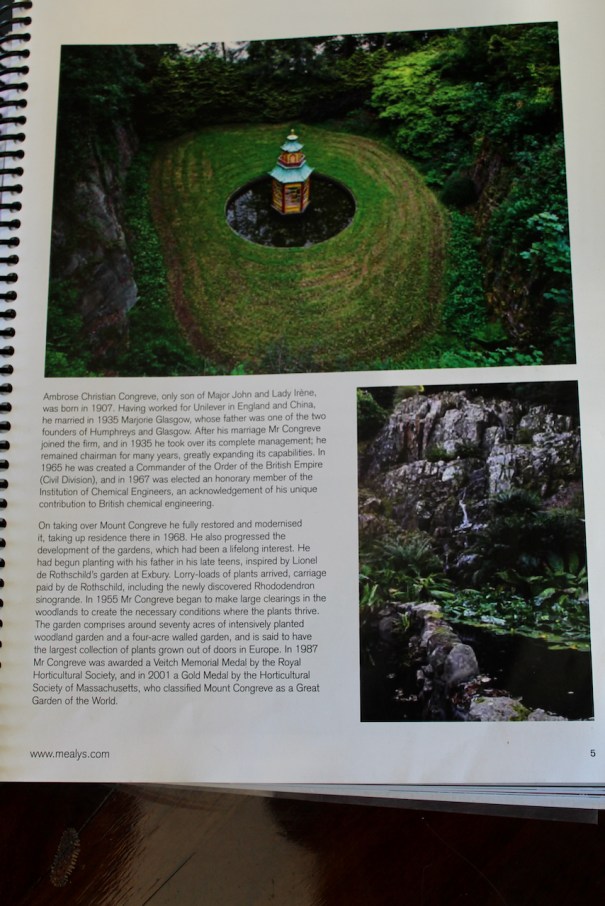

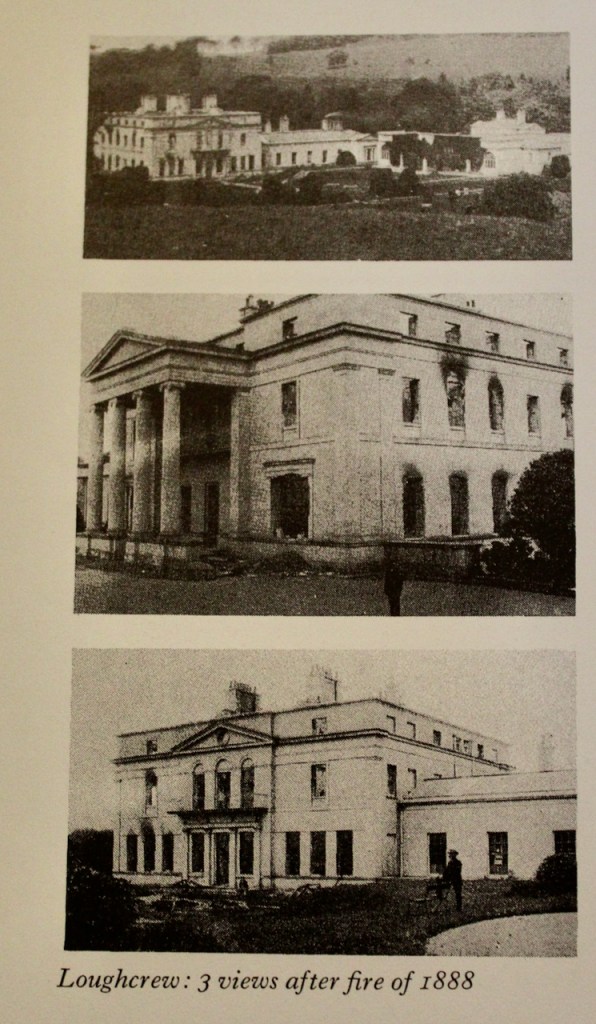

5. Loughcrew House, Loughcrew, Old Castle, Co. Meath – section 482, garden only open to public

Tourist Accommodation Facility Open for accommodation: all year

Since Loughcrew is listed under Revenue Section 482 as Tourist Accommodation facility, it does not have to open to the public. However, the gardens are located nearby and are open to the public.

Garden open dates in 2026: all year

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student €6, child €4, carers free

The website tells us:

“Loughcrew is an estate made up of 200 acres of picturesque rolling parkland complete with a stunning house and gardens. It provides the perfect family friendly day out as there is something to suit all ages and interests.

“The House and Gardens within at Loughcrew Estate date back to the 17th century – making it a landscape of historical and religious significance. Here, you’ll find a medieval motte and St. Oliver Plunkett’s family church among other old buildings. You’ll also find lime and yew avenues, extensive lawns and terraces, a water garden and a magnificent herbaceous border. There is a Fairy Trail for children and a coffee shop too!”

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/21/loughcrew-house-loughcrew-old-castle-co-meath/

6. Moyglare House, Moyglare, Co. Meath W23 RT91 – section 482

See my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/02/15/moyglare-house-county-meath/

Postal address Maynooth Co. Kildare

www.moyglarehouse.ie

Open dates in 2026: Feb 2-6, 9-13, 16-20, 23, 27, June 1-30, July 1, Aug 15-23, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult/OAP €12, child/student €6

7. Oldbridge House, County Meath – Battle of the Boyne Museum – OPW

see my OPW entry, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/07/office-of-public-works-properties-leinster-laois-longford-louth-meath-offaly-westmeath-wexford-wicklow/

8. Slane Castle, Slane, Co. Meath C15 XP83

See my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2019/07/19/slane-castle-county-meath/

www.slanecastle.ie

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open in 2026: every day throughout Feb, May, June, Aug, Sept, Oct, Nov, Mar 1-11, Apr 10-30, July 1-12, 21-31, Dec 1-21

9. St. Mary’s Abbey, Abbey Lane, Trim, Co. Meath – section 482

Open dates in 2026: Apr 20-26, May 6-8, 16-17, June 22-28, July 20-26, Aug 15-23, 31, Sept 1-5, 21-26, Oct 16-21, Nov 23-29, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €5, OAP/student/child €2

See my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/09/17/st-marys-abbey-high-street-trim-co-meath/

10. Swainstown House, Kilmessan, Co. Meath C15 Y60F – section 482

See my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/10/10/swainstown-house-kilmessan-county-meath/

Open dates in 2026: Mar 2-3, 5-6, April 6-7, 9-10, May 4-10, June 1-7, July 6-12, Aug 15-23, Sept 7-11, 14-18, Oct 5-6, 8-9, Nov 2-3, 5-6, Dec 7-8, 10-11, 11am-3pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student/child €5

11. Tankardstown House, Rathkenny, Slane, Co. Meath C15 D535 – section 482, hotel

See my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/11/tankardstown-estate-demesne-rathkenny-slane-co-meath/

www.tankardstown.ie

Open in 2026: all year, National Heritage Week, Aug 15-23, 9am-1pm

Fee: Free to visit.

12. Trim Castle, County Meath – OPW

see my OPW entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/07/office-of-public-works-properties-leinster-laois-longford-louth-meath-offaly-westmeath-wexford-wicklow/

Places to stay, County Meath:

1. Bellinter House near Bective, County Meath – hotel and restaurant

The website tells us:

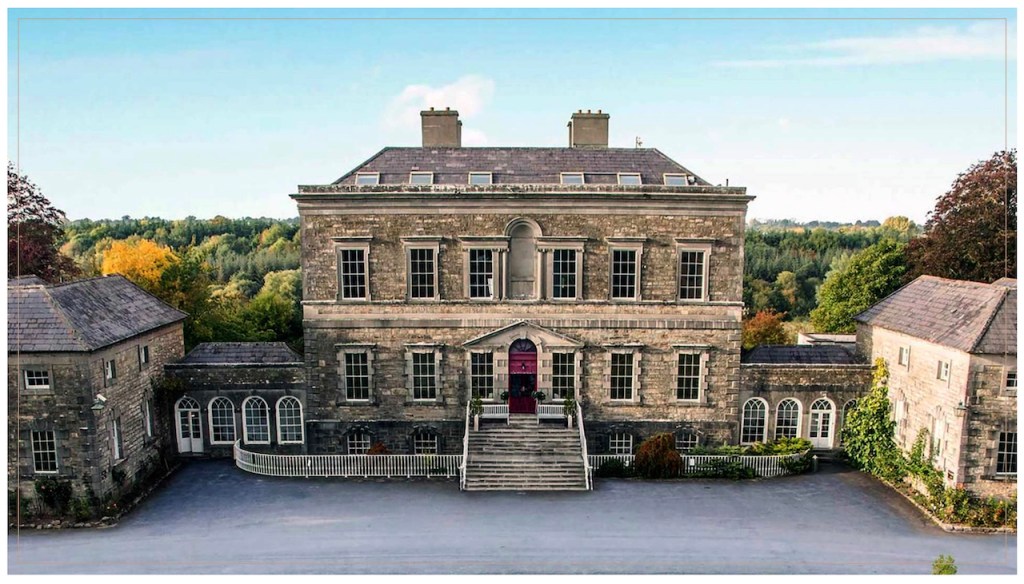

“A magnificent 18th century Georgian house, located in the heart of the Boyne Valley, less than 5 minutes of the M3 and under 30 minutes from Dublin City centre and Dublin airport.

“A property designed originally by Richard Castles for John Preston [1700-1755], this house was once used as a country retreat for the Preston Family, to abscond from the city for the summer months.

“Following over 270 years of beautiful history the purpose of Bellinter House remains the same, a retreat from ones daily life.

“On arriving, you will find yourself succumb to the peacefulness and serenity that is Bellinter House.“

The National Inventory tells us about Bellinter House:

“Designed by the renowned architect Richard Castle in 1751. Bellinter is a classic mid eighteenth-century Palladian house with its two-storey central block, linked to two-storey wings by single-storey arcades, creating a forecourt in front of the house. This creates a building of pleasant symmetry and scale which is of immediate architectural importance. The building is graded in scale from ground to roofline. It gets progressively lighter from semi-basement utilising block and start windows on ground floor to lighter architraves on first floor to cornice. The house forms an interesting group with the surviving related outbuildings and entrance gates.” [4]

Art Kavanagh tells us in his The Landed Gentry and Aristocracy: Meath, Volume 1 (published by Irish Family Names, Dublin 4, 2005) that John Joseph Preston (1815-1892) had only a daughter, and he leased Bellinter House to his friend Gustavus Villiers Briscoe. When John Joseph Preston died he willed his estate to Gustavus.

Much of the land was dispersed with the Land Acts, but Bellinter passed to Gustavus’s son Cecil Henry Briscoe. His son George sold house and lands to the Holdsworth family, who later sold the land to the Land Commission. The house was acquired by the Sisters of Sion in 1966, who sold it in 2003.

[See Robert O’Byrne’s recent post, https://theirishaesthete.com/2022/05/21/crazy-wonderful/ for more pictures of Bellinter.]

2. Boyne House Slane (formerly Cillghrian Glebe), Chapel Street, Slane, Co. Meath C15 P657 – section 482 accommodation

www.boynehouseslane.ie

(Tourists Accommodation Facility)

Open dates in 2026: all year.

The website tells us: “Boyne House Slane is a former rectory dating from 1807, magnificently renewed, whilst retaining much of its original features to offer luxury accommodation comprising 10 guest bedrooms offering exceptional levels of comfort and style, the perfect retreat for the visitor after exploring 5,000 years of history and culture in the area.

“Discreetly tucked away behind the centrally located Village Garden and recreation area, ‘Boyne House Slane’ is set in its own grounds, comprising a small patch of woodland with well-aged Copperbeech, Poplar and Chestnut trees.

“Originally named Cillghrian Glebe, the property was built in 1807 as a rectory or Glebe. The name Cillghrian, sometimes anglicised as Killrian, derives from the words ‘cill’ for church and ‘grian’ which translated as ‘land’ giving the house the simple name ‘church land’. The house retains many of its original features complete with excellent joinery, plasterwork and chimneypieces.”

3. Clonleason Gate Lodge, Fordstown, County Meath: Hidden Ireland

“Our 18th century riverside cottage has been converted into an elegant one bedroom hideaway for a couple. Set in blissful surroundings of gardens and fields at the entrance to a small Georgian house, the cottage is surrounded by ancient oak trees, beech and roses. It offers peace and tranquillity just one hour from Dublin.

“A feature of the cottage is the comfy light filled sitting room with high ceiling, windows on three sides, an open fire, bundles of books and original art. The Trimblestown river, once famous for its excellent trout, runs along the bottom of its secret rose garden. Garden and nature lovers might enjoy wandering through our extensive and richly planted gardens where many unusual shrubs and trees are thriving and where cyclamen and snowdrops are massed under trees. The Girley Loop Bog walk is just a mile down the road.

“The bedroom is luxurious and the kitchen and bathroom are well appointed. There is excellent electric heating throughout.“

“We offer luxury self-catering accomodation in an idyllic setting. Our self-sufficient cottage, furnished and fitted to a high standard, sleeps 2 and boasts a kitchen, a wetroom w/c with a power shower plus ample relaxation space, all kept warm and cosy by a woodburning stove.

“Ideally suited to couples who are looking for a luxurious, romantic break in the peaceful and beautiful countryside of Ireland.“

4. Dunboyne Castle, County Meath

https://www.dunboynecastlehotel.com/

Originally home to The Butlers of Dunboyne, the original Castle on the Dunboyne Estate was destroyed during the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland as a result of the family’s refusal to convert to Protestantism. The ceiling over the staircase depicts the four elements to life at this time; War, Music, Education & Love. The current house was built around 1764, incorporating fabric of earlier house, c.1720, and it was designed by George Darley. [see National Inventory of Architectural Heritage, https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/14341018/dunboyne-castle-maynooth-road-castlefarm-dunboyne-co-meath

5. Highfield House, Trim, County Meath

https://highfieldguesthouse.com

The website tells us:

“Highfield House is an elegant, 18th century residence run by Edward and Geraldine Duignan and situated in the beautiful heritage town of Trim. Known as the birthplace of Ireland’s Ancient East, Trim is renowned as one of Ireland’s most beautiful towns. The award winning accommodation boasts magnificent views of Trim Castle, The Yellow Steeple, and the River Boyne.

“Guests can book Highfield House for their overnight stay while visiting the area, or book the entire property as a self catering option in Meath.

“The house was built in the early 1800’s and was opened as a stately maternity hospital in 1834 and remained so up to the year 1983, making it 175 years old. A host of original, antique interior features still remain. Spend the morning sipping coffee on our patio, relax with a book in our drawing room or wile away the afternoon people watching from our garden across the river.”

6. Johnstown Estate, Enfield, Co Meath – hotel

https://thejohnstownestate.com

The website tells us:

“The original manor – or The Johnstown House as it was known – is as storied as many other large country house in Ireland. Luckily, the house itself has stood the test of time and is the beating heart of the hotel and all its facilities which together form The Johnstown Estate.

“Built in 1761, The Johnstown House (as it was then known) was the country residence of Colonel Francis Forde [1717-1769], his wife Margaret [Bowerbank] and their five daughters. Colonel Forde was the 7th son of Matthew Forde, MP, of Coolgraney, Seaforde County Down, and the family seat is still in existence in the pretty village of Seaforde, hosting Seaforde Gardens.

“The Colonel had recently returned from a very successful military career in India and was retiring to become a country gentleman. Enfield – or Innfield as it was then known – satisfied his desire to return to County Meath where his Norman-Irish ascendants (the de la Forde family) had settled in Fordestown (now Fordstown), Meath, in the 13th century. Enfield was also close to Carton House in Maynooth, the home of the Duke of Leinster – at the time the most powerful landowner in Ireland.

“After 8 years completing the house and demesne and establishing income from his estates, Colonel Forde left for a further military appointment in India. His boat, The Aurora, touched the Cape of Good Hope off Southern Africa on December 27th, 1769 and neither he, nor the boat, were heard from again.

“Thereafter the house was owned by a variety of people including a Dublin merchant, several gentlemen farmers, a Knight, another military man, an MP and a Governor of the Bank of Ireland. In 1927 the Prendergast family bought the house and Rose Prendergast, after whom ‘The Rose’ private dining room is named, became mistress of Johnstown House for over fifty years.

“The house was restored to its previous glory in the early years of the new millennium and a new resort hotel developed around it to become The Johnstown House Hotel. In 2015, under new ownership, the hotel was extensively refurbished, expanded and rebranded to become The Johnstown Estate.“

7. Killeen Mill, Clavinstown, Drumree, Co. Meath – section 482 accommodation

(Tourists Accommodation Facility)

Open for accommodation in 2026: April 1- Sept 30, Mon-Sat

8. Moyglare House, Moyglare, Co. Meath – section 482, see above

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/02/15/moyglare-house-county-meath/

Postal address Maynooth Co. Kildare

www.moyglarehouse.ie

9. Rockfield House Courtyard Apartment, Kells, County Meath

https://rockfieldhouse.com/accommodation/

The Courtyard Apartment is a luxurious two bedroom apartment overlooking the stables.

The fully equipped kitchen has a dining area for five, while the separate lounge room with open fire and plush period furnishings is a lovely space to relax after a busy day.

Outside, you can ramble around the grounds, check for eggs as you go or visit the Fred and Ted our resident (and rather free-spirited) goats – or they might visit you!.

Rates at time of publication (check website):

1 person – 1 night €150 2 nights €300

2 people – 1 night €160 2 nigts €320

3 people – 1 night €225 2 nights €420

4 people – 1 night €280 2 nights €520

5 people – 1 night €320 2 nights €600

10. Rosnaree, Slane, Co Meath – accommodation

https://www.facebook.com/theRossnaree/

The website tells us: “This stylish historic country house in Slane, County Meath, offers boutique bed and breakfast with magnificent views across the Boyne Valley and the megalithic passage tomb of Newgrange.

“Rossnaree (or “headland of the Kings”) is a privately owned historic country estate in Slane, County Meath, located only 40 minutes from Dublin and less than an hour from Belfast.

“An impressive driveway sweeps to the front of Rossnaree house, standing on top of a hill with unrivalled views across the River Boyne to Ireland’s famous prehistoric monuments, Knowth, Dowth and Newgrange.

“Rossnaree has been transformed into a boutique bed and breakfast, offering four luxury rooms for guests and also an original venue for special events and artistic workshops.“

11. Ross Castle, Mountnugent, County Meath whole castle for 10 or self-catering accommodation

See my County Cavan entry, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/03/county-cavan-historic-houses-to-see-and-stay/

12. Slane Castle, County Meath C15 XP83

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open in 2026: every day throughout Feb, May, June, Aug, Sept, Oct, Nov, Mar 1-11, Apr 10-30, July 1-12, 21-31, Dec 1-21

13. Tankardstown House, Rathkenny, Slane, Co. Meath – section 482, boutique hotel

See my entry:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/11/tankardstown-estate-demesne-rathkenny-slane-co-meath/

Whole house booking/wedding venues, County Meath

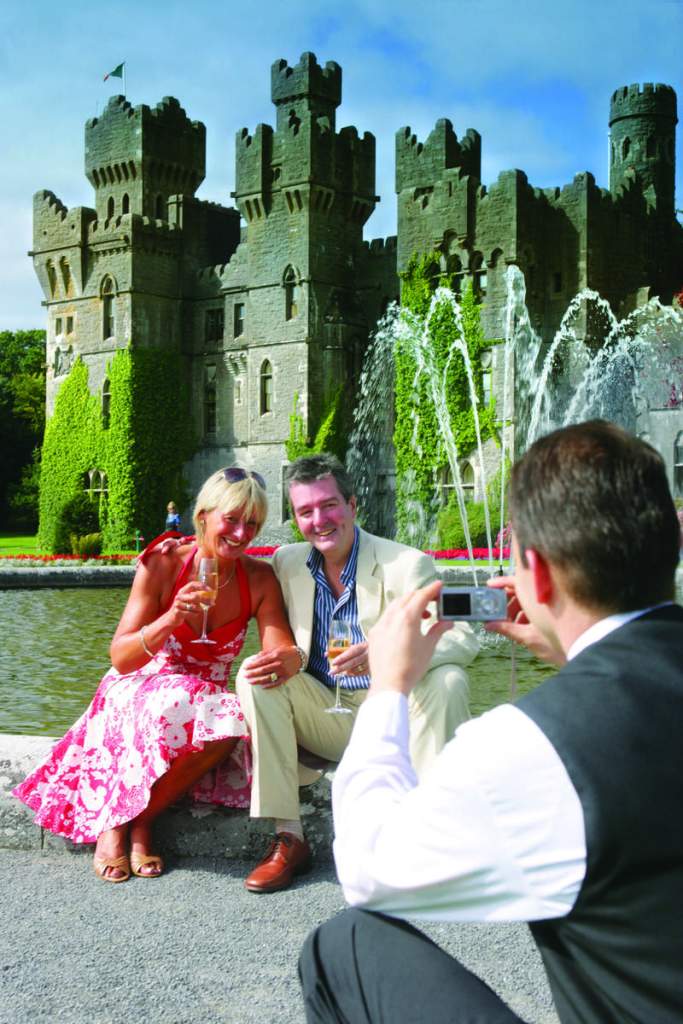

1. Ballinlough Castle, Clonmellon, Navan, County Meath – Whole house booking/wedding venues

https://www.ballinloughcastle.ie/

The website tells us Ballinlough Castle is available for exclusive hire of the castle and the grounds (minimum hire 3 nights) is available for private or corporate gatherings. Focussing on relaxed and traditional country house hospitality, assisted by a local staff.

The website tells us of its history:

“The Nugent family at Ballinlough were originally called O’Reilly, but assumed the surname of Nugent in 1812 to inherit a legacy. They are almost unique in being a Catholic Celtic-Irish family who still live in their family castle.

“The castle was built in the early seventeenth century and the O’Reilly coat of arms over the front door carries the date 1614 along with the O’Reilly motto Fortitudine et Prudentia.

“The newer wing overlooking the lake was added by Sir Hugh O’Reilly (1741-1821) in the late eighteenth century and is most likely the work of the amateur architect Thomas Wogan Browne, also responsible for work at Malahide Castle, the home of Sir Hugh O’Reilly’s sister Margaret.

“Sir Hugh was created a baronet on 1795 and changed the family name in 1812 in order to inherit from his maternal uncle, Governor Nugent of Tortola.

“As well as the construction of this wing, the first floor room above the front door was removed to create the two-storey hall that takes up the centre of the original house. The plasterwork here contains many clusters of fruit and flowers, all different. A new staircase was added, with a balcony akin to a minstrel’s gallery, and far grander than the original staircase that still remains to the side.

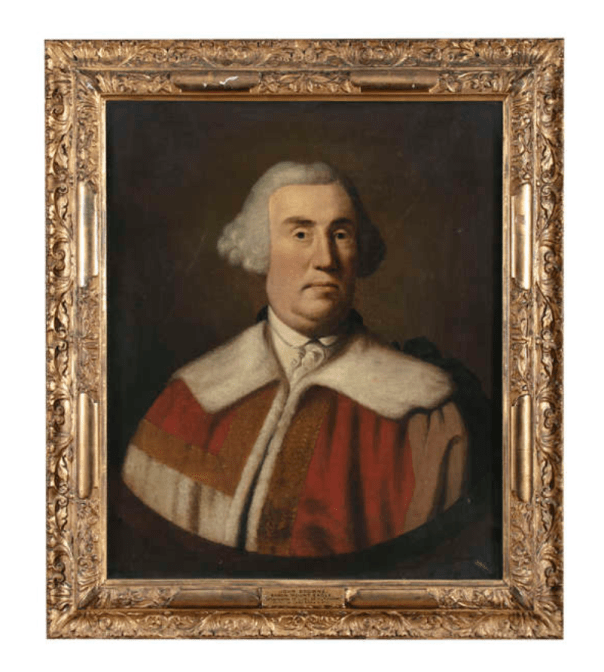

“Sir Hugh’s younger brothers James and Andrew entered Austrian military service, the latter becoming Governor-General of Vienna and Chamberlain to the Emperor. His portrait hangs in the castle’s dining-room.

“The family traces directly back to Felim O’Reilly who died in 1447. Felim’s son, John O’Reilly was driven from his home at Ross Castle near Lough Sheelin and settled in Kilskeer. His grandson Hugh married Elizabeth Plunket with whom he got the estate of Ballinlough, then believed to have been called Bally-Lough-Bomoyle. It was his great-grandson James who married Barbara Nugent and about whom an amusing anecdote is told in Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine of 1860:

During the operation of the penal laws in Ireland, when it was illegal for a Roman Catholic to possess a horse of greater value than five pounds, he was riding a spirited steed of great value but being met by a Protestant neighbour who was on foot, he was ordered by him to relinquish the steed for the sum of five pounds sterling. This he did without hesitation and the law favoured neighbour mounted his steed and rode off in haughty triumph. Shortly afterwards, however, James O’Reilly sued him for the value of the saddle and stirrups of which he was illegally deprived and recovered large damages.

“The investment in the castle by James’ son, Hugh was recorded in The Irish Tourist by Atkinson 1815, which contained the following account of a visit to Ballinlough:

The castle and demesne of Ballinlough had an appearance of antiquity highly gratifying to my feelings ….. I reined in my horse within a few perches of the grand gate of Ballinlough to take a view of the castle; it stands on a little eminence above a lake which beautifies the demesne; and not only the structure of the castle, but the appearance of the trees, and even the dusky colour of the gate and walls, as you enter, contribute to give the whole scenery an appearance of antiquity, while the prospect is calculated to infuse into the heart of the beholder, a mixed sentiment of veneration and delight.

Having visited the castle of Ballinlough, the interior of which appears a good deal modernised, Sir Hugh had the politeness to show me two or three of the principal apartments; these, together with the gallery on the hall, had as splendid an appearance as anything which I had, until that time, witnessed in private buildings. The rooms are furnished in a style- I cannot pretend to estimate the value, either of the furniture or ornamental works, but some idea thereof may be formed from the expenses of a fine marble chimney-piece purchased from Italy, and which, if any solid substance can in smoothness and transparency rival such work, it is this. I took the liberty of enquiring what might have been the expense of this article and Sir Hugh informed me only five hundred pounds sterling, a sum that would establish a country tradesman in business! The collection of paintings which this gentleman shewed me must have been purchased at an immense expense also- probably at a price that would set up two: what then must be the value of the entire furniture and ornamental works?

“Sir Hugh was succeeded in the baronetcy by his eldest son James, who was succeeded by his brother Sir John, who emulated his uncle in Austria in becoming Chamberlain to the Emperor. His eldest son Sir Hugh was killed at an early age so the title then passed to his second son Charles, a racehorse trainer in England. Sir Charles was an unsuccessful gambler which resulted in most of the Ballinlough lands, several thousand acres in Westmeath and Tipperary being sold, along with most of the castle’s contents.

“Sir Charles’ only son was killed in a horseracing fall in Belgium in 1903, before the birth of his own son, Hugh a few months later. Sir Hugh inherited the title on the death of his grandfather in 1927 and, having created a number of successful businesses in England, retuned to Ballinlough and restored the castle in the late 1930s. His son Sir John (1933- 2010) continue the restoration works and the castle is now in the hands of yet another generation of the only family to occupy it.”

2. Boyne Hill estate, Navan, County Meath – whole house rental

“Set in 38 acres of pretty gardens and parklands and just 35 minutes from Dublin, this stunning country house estate becomes your very own private residence for your special day.“

3. Durhamstown Castle, Bohermeen, County Meath – whole house rental

“Durhamstown Castle is 600 years old inhabited continuously since 1420. Its surrounded by meadows, dotted with mature trees. We take enormous pleasure in offering you our home and hospitality.“

The website tells us that in 1590:

“The Bishop of Meath, Thomas Jones [1550-1619], who resided in next door Ardbraccan, at this time, owned Durhamstown Castle & we know from the records, that he left it to his son, Lord Ranelagh, Sir Roger Jones; who was Lord President of Connaught. Thomas Jones was witness & reporter to the Crown on negotiations between the Crown Forces & the O’Neills. He was known to be close to Robert Devereux, The Earl of Essex – Queen Elizabeth’s lover. (Later, executed for mounting a rebellion against Her.) Letters are written – copies of which are in the National Library – from Devereux to the Queen both from Ardbraccan & Durhamstown (“the Castle nearby”).

“Roger Jones, 1st Viscount Ranelagh (before 1589 – 1643) was a member of the Peerage of Ireland and lord president of Connaught. He was Chief Leader of the Army and Forces of Connaught during the early years of the Irish Confederate Wars. In addition to Viscount Ranelagh, he held the title Baron Jones of Navan.

“Jones was the only son of Archbishop of Dublin and Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Thomas Jones, and his wife Margaret Purdon. He was knighted at Drogheda on 24 March 1607. In 1609, he married Frances Moore, the daughter of Sir Garret Moore, eventual 1st Viscount Moore of Drogheda. Jones was a member of the Parliament of Ireland for Trim, County Meath from 1613 to 1615. In 1620, he was named to the privy council of Ireland. He was the Chief Leader of the Army and Forces of Connaught and was Vice President of Connaught from 1626.

“In 1608 his father became involved in a bitter feud with Lord Howth, in which Roger also became embroiled. His reference to Howth as a brave man among cowards was enough to provoke his opponent, a notoriously quarrelsome man to violence. In the spring of 1609, Jones, Howth and their followers engaged in a violent fracas at a tennis court in Thomas Street, Dublin, and a Mr. Barnewall was killed. The Lord Deputy of Ireland, Sir Arthur Chichester, an enemy of Howth, had him arrested immediately, though he was never brought to trial.

“On 25 August 1628, Jones was created Baron Jones of Navan and 1st Viscount Ranelagh by King Charles I. He was made Lord President of Connaught on 11 September 1630 to serve alongside Charles Wilmot, 1st Viscount Wilmot.

“Jones was killed in battle against Confederate forces under the leadership of Owen Roe O’Neill in 1643.

“An Uncle, Colonel Michael Jones, was the military Governor of Dublin at the time and supported Cromwell’s landing at Ringsend, after the Battle of Rathmines. Troops assembled at Durhamstown to fight on Cromwell’s side. When they marched on Drogheda they laid the place waste & murdered all before them. They brought the severed heads of the Royalist Commanders to Dublin. The Jones’ generally seem to have been a bloodthirsty lot; & were known to be unrelenting in their enforcement of the new Credo. Michael Jones even had his own nephew executed. Roger Jones’ son, Arthur was also embroiled in huge controversy when, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was supposed to have diverted all the taxes to pay for the King’s Mistresses!

“[From 1750] From this time onwards we think the Thompsons lived here. One of the Thompsons was said to have died from septicaemia as a result of an apoplectic rage caused by his Irish labourers refusing to knock down the Church of Durhamstown. He is alleged to have grabbed the shovel & attempted the work himself ; only for the shovel to bounce back & bury itself in his leg, or in some recordings it hacked off his leg; which subsequently became septic & “he died miserably from his wounds” But the stones & spire were taken to build Ardbraccan Church.“

In 1840 “One of the Thompsons married a Roberts from Oatlands just at the back of Durhamstown, & they lived here up until 1910. A couple of years ago Janice Roberts, from America, called to the House but we were out!! Luckily Ella, a neighbour realised the importance of it & arranged for her & her husband to call back. We had a fascinating afternoon going through old photographs & records & tramping quietly round the nearby graveyards with them, filling in the blanks. She promised us a photograph of an oil painting of the Castle intact. Her grandfather lived in Durhamstown & later he sold it, taking some of the furniture & artefacts to his house in Dalkey, called Hendre.“

In 1996 Sue (Sweetman) & Dave Prickett buy Durhamstown Castle. “And we have been working on it ever since! We have re-roofed the entire Castle & the majority of the Buildings in the Yard. It was in a ruinous state when we bought it.“

4. Loughcrew House, Loughcrew, Old Castle, Co. Meath – section 482, whole house booking

See above, under places to visit.

5. Mill House, Slane – weddings

The website tells us:

“Built in 1766, The Millhouse and The Old Mill Slane, the weir and the millrace were once considered the largest and finest complex of its kind in Ireland. Originally a corn mill powered by two large water wheels, the harvest was hoisted into the upper floor granaries before being dried, sifted and ground.

”Over time, the Old Mill became a specialised manufacturer of textiles turning raw cotton into luxury bed linen. Times have changed but this past remains part of our history, acknowledged and conserved.

”In 2006, The Millhouse was creatively rejuvenated, transformed into a hotel and wedding venue of unique character – a nod to the early 1900’s when it briefly served as a hotel-stop for passengers on pleasure steamer boats.”

7. Rockfield House, Kells, County Meath

“The Murtagh Family welcomes you to Rockfield House. Located just outside the heritage town of Kells in Co. Meath, in the heart of the Boyne Valley and Irelands Ancient East, originally built in the 18th century, the house has recently been restored to its former glory but with 21st century comforts.

“Sitting on 68 Acres of lush green fields, with 10 bedrooms sleeping up to 30 people and a separate Courtyard 2 bedroom apartment with its own entrance which can accommodate a further 5 people, there is an abundance of space to entertain and and be entertained.“

“Rockfield House was built by Thomas Rothwell at the end of the eighteenth century. His son Richard carried out improvements around 1840/41. At the time it was built, the Rothwell family owned well over 3,000 acres in County Meath. Thomas Rothwell married Louisa Pratt, daughter of Mervin Pratt and his wife Madeline Jackson of Cabra Castle and Enniscoe House, respectively. Over the generations, the Rothwells married local land-owning families, including Nicholson (Balrath Bury) and Fitzherbert (Blackcastle).

“During the 20th century it was owned by the Pigeon and Cameron families and at the turn of the 21st Century it was purchased by Trevor and Bernie Fitzherbert (originally from Blackcastle Estate). They carried out a substantial programme of refurbishment and redecoration and returned the house and surrounding courtyards and walled garden to its former glory.

“In 2022 the house was purchased by the Murtagh family, from nearby Causey Farm, with the intention of using it as a place to support foster families with their Nurturing in Nature programme. The current owners also intend to continue the tradition of parties and events that Rockfield has been renowned for over the centuries.“

8. Ross Castle, Mountnugent, County Meath whole castle for up to 10 people or self-catering accommodation

See my County Cavan entry, https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/03/county-cavan-historic-houses-to-see-and-stay/

[1] https://meathhistoryhub.ie/houses-a-d/

[2] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Hamwood

[3] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[4] https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/14403107/bellinter-house-ballinter-meath

[5] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Killyon%20Manor%20

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com