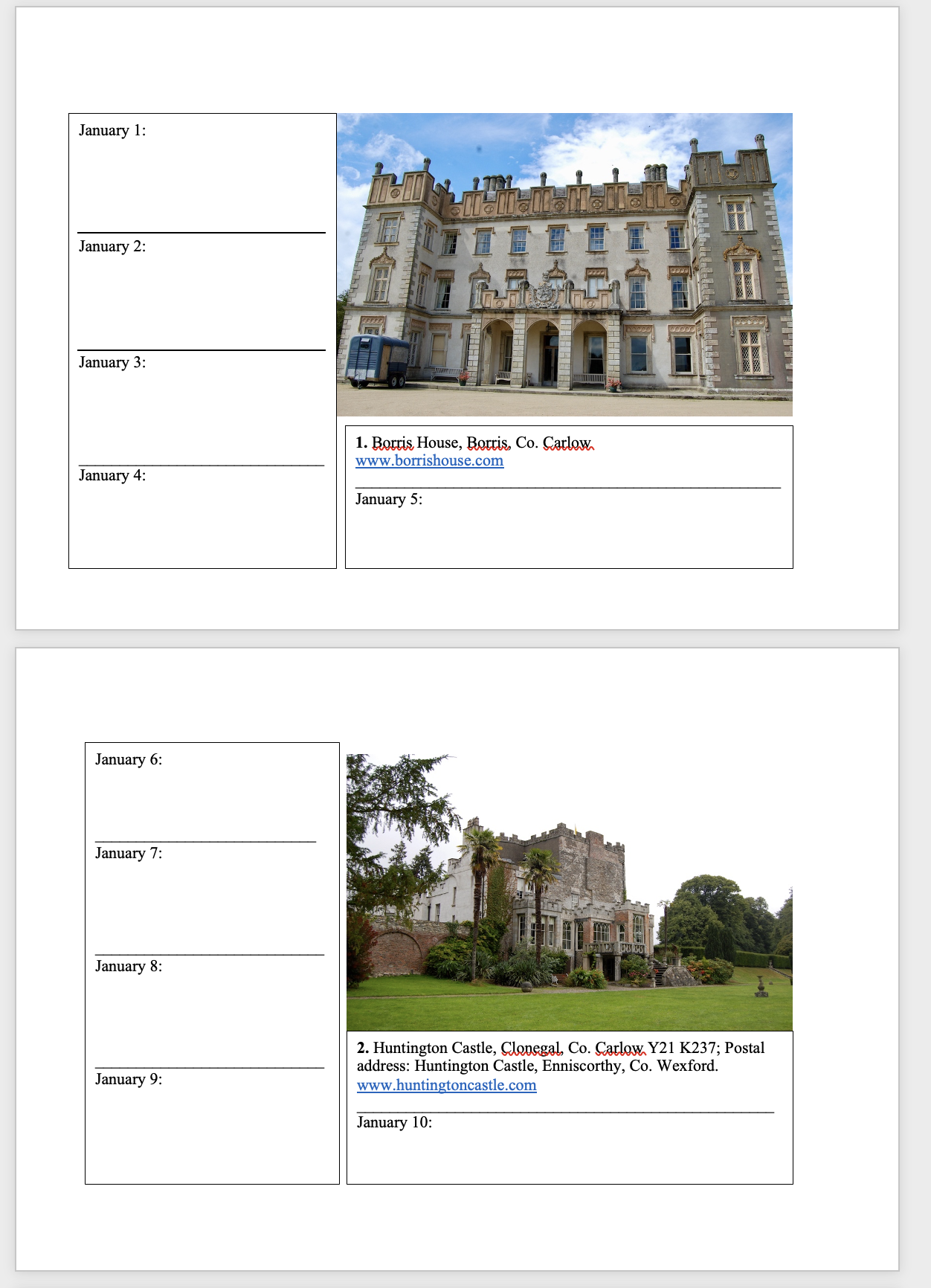

On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Kerry:

Places to Stay, County Kerry:

1. Ard na Sidhe Country House, Killarney, County Kerry – luxury 4* hotel

2. Ballyseede Castle/ Ballyseedy (Tralee Castle), Tralee, County Kerry –hotel

3. Barrow House, Barrow West, Ardfert, Tralee, Kerry, V92 Y270 – B&B or exclusive rental

4. Cahernane (or Cahirnane) House, Killarney, County Kerry – hotel

5. Carrig Country House, County Kerry

6. Dromquinna Estate, County Kerry – self catering in adjunct buildings, weddings

7. Glanleam, Valentia Island, County Kerry – accommodation

8. Keel House, Keel, Castlemaine, Co. Kerry V93 A6 Y3 – section 482 accommodation

9. Kells Bay House & Garden, Kells, Caherciveen, County Kerry

10. Muxnaw Lodge, Kenmare, County Kerry

11. Parknasilla Resort and Spa, Kenmare, County Kerry

Whole House Rental and wedding venues in County Kerry:

1. Ballywilliam House, Kinsale, County Kerry – whole house rental, up to 16

2. Churchtown House, Killarney, County Kerry – whole house rental (sleeps 12)

3. Coolclogher House, Killarney, County Kerry – luxury vacation rental manor (up to 14 people)

4. Dromquinna Estate, County Kerry – self catering in adjunct buildings, weddings

Places to Stay, County Kerry:

1. Ard Na Sidhe, Killarney, County Kerry luxury 4* hotel

“Ard na Sidhe Country House is a place of enchantment and wondrous luxury, an intimate hideaway set on 32 acres of natural woodland on the shores of Caragh Lake.

“Inviting lounges with an open log fire, intimate dining and 18 luxurious guest rooms, it really is possible to feel a world away in this magical gem. Come and share the dream.

“When you arrive at Ard na Sidhe Country House Hotel you are instantly transported to a stunning world away. Translated as ‘the Hill of the Fairie,’ the majestic panorama of this four star lake hotel on Caragh Lake, Killorglin in County Kerry envelops you completely. A luxurious country manor house built by Lady Gordon in 1913, Ard na Sidhe is highly regarded as one of the best four star hotels in Ireland.

“The ethereal architecture and surrounds of this leading country manor house hotel provide an exquisite ambience that make it a landmark destination for secluded Irish accommodation. Victorian styling offers an enthralling sense of history and heritage set against the Ring of Kerry’s breathtaking scenery. Ard na Sidhe’s sumptuous décor and award winning gardens make it a blissful destination for adventure, relaxation and romance in The Reeks District and near the Lakes of Killarney. From the hotel’s doorstop, you’ll feel the heartbeat of this famed region where inspiring tranquility awakens you and modern comforts shroud you at every turn.“

2. Ballyseede Castle, Tralee, Co. Kerry – section 482, also a hotel for accommodation

www.ballyseedecastle.com

Open dates in 2026: Mar 14-Dec 31, 9am-11pm

Fee: Free to visit.

We treated ourselves to a stay in 2023. See my entry: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/02/ballyseede-castle-ballyseede-tralee-co-kerry/

3. Barrow House, Barrow West, Ardfert, Tralee, Kerry, V92 Y270 – B&B or exclusive rental

The website https://www.barrowhouse.ie/ tells us the House and Gardens are available for bed & breakfast guests or as an exclusive venue for corporate functions, private group rentals and intimate, small scale weddings. They are members of the Historic Houses of Ireland association, which tells us of the history of the house:

“Nestling on the shore of stunning Barrow Harbour with views of the glorious Slieve Mish Mountains, Barrow House in Co. Kerry has a rich history of ownership from knights to noblemen and smugglers.

“Built in around 1715, it possibly incorporates the fabric of an earlier house from during or after the Cromwellian period (1649-57). The sublime Georgian front elevation of Barrow House was added as part of the structural rebuild and enlargement work carried out at some point before 1760, while a second sympathetic addition was made at the rear towards the end of the 1800s. The house has changed little over the years. In fact, its still-visible four-feet thick internal walls, two gable end chimney stacks, original interior features, handcrafted ceiling mouldings and sash windows with antique glass exude the restrained, rational elegance typical of a noble dwelling.

“Alongside is a detached seven-bay single- and two-storey former boathouse, c. 1800, on a U-shaped plan. Barrow’s lands were originally part of the 6,000 acres granted by Elizabeth 1 in 1587 to Sir Edward Denny for his loyalty following the Desmond Rebellion. Nearby are the ruins of an ancient church referred to in Papal documents 1302-07 as “Ecclesia of Barun” or the Church of Barun (Barrow).

“Over the centuries, the house and the estate were passed on through marriage or by sale to different owners, including the notorious smuggler, John Collis. The smuggling of wines and tobacco was prevalent in Kerry during the 17th and 18th centuries in particular and Barrow Harbour was a natural rendezvous with its caves and narrow inlets. In the first half of the 20th century, the Knights of Kerry, the Fitzgerald family, affectionately referred to Barrow House as their summerhouse. In more recent years, it was purchased by an American, Maureen Erde, who published a popular account of running it as a golfers’ guesthouse entitled “Help me, I’m an Irish Inn Keeper”. After she sold it in 1999, the house was restored as a resort estate, flourishing for some years before enduring a period of neglect and abandonment. Barrow House’s current owner, Daragh McDonagh, purchased it in 2016 and has lovingly restored it to welcome guests.“

4. Cahernane (or Cahirnane) House, Killarney, Co Kerry – hotel

The website tells us:

“Beautifully situated on a private estate on the edge of Killarney National Park, our luxury four-star hotel is located just twenty minutes’ walk from Killarney town centre. The entrance to the hotel is framed by a tunnel of greenery which unfurls to reveal the beauty of this imposing manor house, constructed in 1877 and formerly home to the Herbert Family.

“Cahernane House Hotel exudes a sense of relaxation and peacefulness where you can retreat from the hectic pace of life into a cocoon of calmness and serenity. The only sounds you may hear are the lambs bleating or the birds singing.

“Cahernane House was built as the family residence of Henry Herbert in 1877 at a cost of £5,992. The work was carried out by Collen Brothers Contractors. The original plans by architect James Franklin Fuller, whose portfolio included Ballyseedy Castle, Dromquinna Manor and the Parknasilla Hotel, was for a mansion three times the present size.“

5. Carrig Country House, County Kerry – B&B

The website tells us: “If you are looking for the perfect hideaway which offers peace, tranquility, plus a wonderful restaurant on the lake, Carrig House on the Ring of Kerry and Wild Atlantic Way is the place for you. The beautifully appointed bedrooms, drawing rooms and The Lakeside Restaurant, overlooking Caragh Lake and surrounded by Kerry’s Reeks District mountains, rivers and lakes create the perfect getaway.

“Carrig House was built originally circa 1850 as a hunting lodge, it was part of the Blennerhassett Estate. It has been mainly owned and used by British Aristocracy who came here to hunt and fish during the different seasons.

“The house was purchased by Senator Arthur Rose Vincent in the early 20th. Century. Vincent moved here after he and his wealthy Californian father in law Mr. Bowers Bourne gave Muckross House & Estate in Killarney to the Irish Government for a wonderful National Park.

“Bourne had originally purchased Muckross House from the Guinness family and gave it to his daughter Maud as a present on her marriage to Arthur Rose Vincent. However, Maud died at a young age prompting Bourne and Vincent to donate the estate to the Irish State.

“Vincent remarried a French lady and lived at Carrig for about 6 years, they then moved to the France. The country house history doesn’t end there, Carrig has had many other illustrious owners, such as Lady Cuffe , Sir Aubrey Metcalfe, who retired as the British Viceroy in India and Lord Brocket Snr, whose main residence was Brocket Hall in England.

“Frank & Mary Slattery, the current owners purchased the house in 1996. They are the first Irish owners of Carrig since it was originally built and have renovated and meticulously restored the Victorian residence to its former glory.

“For over two decades Frank & Mary have operated a very successful Country House & Restaurant and have won many rewards for their hospitality and their Lakeside Restaurant. They are members of Ireland’s prestigious Blue Book.

“Carrig House has 17 bedrooms, each individually decorated in period style with antique furniture. Each room enjoys spectacular views of Caragh Lake and the surrounding mountains. All rooms are en suite with bath and shower. Those who like to indulge can enjoy the sumptuous comfort of the Presidential Suite with its own separate panoramic sitting room, male and female dressing rooms and bathroom with Jacuzzi bath.

“The restaurant is wonderfully situated overlooking the lake. The atmosphere is friendly, warm and one of total relaxation. The menu covers a wide range of the freshest Irish cuisine.

“Irish trout and salmon from the lake and succulent Kerry lamb feature alongside organic vegetables. Interesting selections of old and new world wines are offered to compliment dinner whilst aperitifs and after-dinner drinks are served in the airy drawing room beside open peat fires.

“Within the house, chess, cards and board games are available in the games room.“

6. Dromquinna Estate, Co Kerry – self catering in adjunct buildings, weddings

https://www.dromquinnamanor.com

It was constructed for Sir John Columb around 1889-90. The website tells us:

“There are many elements to Dromquinna Manor. Firstly it is a stunning waterside estate unlike anything else. Set on 40 acres of parkland planted in the 1800s, the Estate offers an abundance of activities and facilities.

“The Manor, dating from the 1890s, is dedicated to catering for Weddings and events. The Oak Room is the heart of the Manor and is classical in every sense. Stylish beyond words with views of Kenmare Bay celebrations here are truly memorable. The Drawing Rooms and Terrace all make for a very special and memorable occassion for all. It is a real family and friends party as opposed to a hotel ballroom function.”

7. Glanleam, Valentia Island, Co Kerry – accommodation

https://hiddenireland.com/house-pages/glanleam-house/

The website tells us:

“Glanleam was built as a linen mill in 1775 and later converted into a house by the Knight of Kerry, who planted the magnificent sub-tropical gardens. In 1975 Meta Kreissig bought the estate which had declined for 50 years. She rescued the house, restored and enlarged the garden and, with her daughter Jessica, made it a delightful place to stay, with a mixture of antique and contemporary furniture and an extensive library. The setting looking out over the harbour is magical. There are green fields, a beach and a lighthouse, and Valentia Island is connected to the Kerry mainland by a car ferry and a bridge.

“Glanleam was converted into a country house by the 19th Knight of Kerry (1808-1889). His father had developed the famous Valentia slate quarry (the slates were especially in demand for billiard tables, then very much in vogue). The Knight, an enthusiastic botanist, recognised the unique potential of the island’s microclimate for sub-tropical plants and laid out a fifty acre garden, using species just introduced from South America. His efforts won him great acclaim at the time and today his gardens have matured into dense woodlands.

“Together Meta Kreissig and her daughter Jessica have refurbished the house, furnishing it with an amalgam of antique and modern pieces, and opened it to guests. There is an extensive library, several of the rooms have their original Valentia slate chimneypieces, and the bedrooms have luxurious Bonasck designer bathrooms. The gardens have also benefited from their attention. One recent visitor described the ‘radial planting of vegetables’ in the centre of the walled kitchen garden as ‘a jewel’.“

8. Keel House, Keel, Castlemaine, Co. Kerry V93 A6 Y3 – section 482 accommodation

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open for accommodation in 2026: April 1- Oct 15 2026

https://www.airbnb.ie/rooms/763099850152850482?source_impression_id=p3_1741194866_P3bysbQjjoOVpVMf

9. Kells Bay House & Garden, Kells, Caherciveen, Co Kerry, V23 EP48 – accommodation and gardens

See my entry, but note tha in 2026 it is no longer listed on the Revenue Section 482.

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/13/kells-bay-house-garden-kells-caherciveen-county-kerry/

The website tells us: “Kells Bay Gardens is one of Europe’s premier horticultural experiences, containing a renowned collection of Tree-ferns and other exotic plants growing in its unique microclimate created by the Gulf Stream. It is the home of ‘The SkyWalk’ Ireland’s longest rope-bridge.“

10. Muxnaw Lodge, Kenmare, Co Kerry – accommodation

https://www.muxnawlodgekenmare.com/

The website tells us that Muxnaw Lodge in Kenmare is an attractive Victorian house, with spectacular views of the Kenmare River and Suspension Bridge.

Muxnaw Lodge features in Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe’s Voices from the Great Houses: Cork and Kerry. Mercier Press, Cork, 2013:

p. 242. “John Desmond Calverley Oulton (konwn as Desmond), who was born at Clontarf Castle in 1921, is the son of John George Oulton and Sybil Mona Calverley. He has long and loving memories of his childhood home at Clontarf Castle, where he played with his siblings in truly magical surroundings…”

p. 245. “During his childhood days, Desmond and his family would travel to Kerry each summer to stay at Muxnaw Lodge at Kenmare, which had been owned for generations by his mother’s people, the Calverleys. A lovely gabled building, the Lodge was built in 1801 as a hunting and fishing lodge by the Calverley family. It is situated on a spectacular site overlooking the Kenmare River and is now run as an up-market guesthouse.

The name Muxnaw comes from the Irish Mucsnamh (the swimming place of the pigs). Joyce’s Irish Place Names gives this explanation:

“The natural explanation seems to be that wild pigs were formerly in the habit of crossing… at this narrow point. The Kenmare River narrowed at this point by a spit of land projecting from the northern shore, and here in past ages, wild pigs used to swim across so frequently, and in such numbers, that the place was called Muscnamh or Mucksna.”

p. 245. “Desmond explains the complexities of his family history: “Colonel Vernon, owner of Clontarf Castle, had several daughters and a son. One daughter, Edith Vernon, married Walter Calverley who owned Muxnaw Lodge. They had two children, my mother, Sybil Mona Calverley, and Walter Calverley. Walter was killed during the first world war, and following the death of Walter Calverley Sr, Muxnaw Lodge went to his brother, Charles, who left it to his niece, my mother.” “

11. Parknasilla Resort and Spa, Kenmare, Co Kerry – hotel

The website tells us:

“Parknasilla Hotel, nestled in the shadows of the Kerry mountains amidst islands, inlets and hidden beaches.

“Come stay with us and feel the restorative power of nature and marvel in the splendour of the seascape and landscape that surrounds you here.

“The word Parknasilla ,(means the field of Sallys) [perhaps “salix” meaning Willow], for so many is evocative of so many things, tucked away in the corner of a subtropical paradise on the Kenmare river , it’s a place of beauty, of rare plants, islands linked by timber bridges and coral inlets.

“Where the sea, the light and clouds put on a continual show to delight the senses. A place where people come as guests and leave as friends, with its tradition of hospitality stretching back over 125 years. It has hosted royalty, dignitaries, family gatherings and romantic get aways.

“It has provided people with that peaceful haven for them to recalibrate and recharge their batteries but it has also been that place of quite inspiration for writers and artist from George Bernard Shaw to Ceclia Ahern .

“With its winding walks, this 200 acre estate walled gardens, golf course, island dotted bay and spa coupled with a world class resort with a 4 star hotel houses and apartments it provides one with that perfect retreat to suit all tastes.

“It is a place of many layers constantly evolving, seen through the prism of history it’s a place where people create their own be it in the friends formed or memories laid down to last a life time, a place to return to again.”

The website tells us about the history of Parknasilla:

“The origins of the rise of the Great Southern Hotels and Parknasilla arised from the middle of the 19th century. Despite the ravages of the famine, Ireland was seen as an exotic tourism destination and this was particularly true after Queen Victoria’s trip to Ireland and Kerry in 1861, that saw an explosion of tourism from overseas. Railway lines were developed in the mid 1850’s from Dubin to remote towns of Killarney, Dingle, Galway and Sligo and later new lines were developed from Killarney for instance to Kenmare.

“In the South of Ireland, the most import railway was the Great Southern and Western Dublin-Cork Link that opened in 1849. Excursions were promoted and resort hotels that were built were to supplied with customers by new railway line. New doors opened for Parknasilla around the start of the 1890’s, when in 1893 Kenmare became the terminuis of the branch line. Subsequently two years earlier, the Derryquin Estate was in 1891 by the Bland family in various lots. Bishop Graves of Limerick who had leased the part of the property for a long period off the Blands, purchased in one lot, and only a short time after sold the property to the Great Southern Hotel Group.

“On the 1st of May 1895, The Southern Hotel Parknasilla opened, the name Parknasilla which means “The field of the willows” began to appear on the maps. It was also refered to as the “Bishops House Hotel, Parknasilla”. The story of the construction of architecture is also an interesting one. Eminent architect James Franklin Fuller was chosen by the Great South and Western Railway, prior 1895. Fuller himself left an incredible legacy behind, he was responsible for the designs of some of Ireland’s most iconic buildings such as Kylemore Abbey, Ashford Castle, Kenmare Park (formely the Great Southern Kenmare) and Farmleigh House.

“Born in 1835 in Kerry, he was the only son of Thomas Harnett Fuller of Glashnacree by his first wife, Frances Diana, a daugther of the Francis Christopher Bland of Parknasilla dn Derryquin Castle. The Blands were indeed synomous with Parknasilla for over two centuries, and new chapter for Parknasilla future now had an incredible link with its past.

“The hotel originally started out in what was known as “The Bishops House”, however a better position was chosen in 1897 for a new purpose buillt hotel. The new Parknasilla Hotel faced down the Kenmare Bay an offered its guests uparelled views of the Atantic Ocean. The facilties of the new hotel included Turkish Hot and Cold Seawater Baths, reading and games rooms and bathrooms on every floor. This decision came after unprecedented demand that well exceed supply.“

The website also tells us about the early owners of the property:

“The Blands of Derryquin Castle Demense were a Yorkshire family, the first of whom Rev. James Bland came to Ireland in 1692 and from 1693 was vicar of Killarney. His son Nathaniel, a judge and vicar general of Ardfert and Aghadoe obtained a grant of land in 1732 which would later become the Derryquin Estate. Derryquin Castle was the third house of the Blands on this land but it is not known when it was first constructed, its earliest written mention being in 1837, however it was indicated some decades earlier by Nimmo in his 1812 map.

“The estate is said to have reached its zenith under the guidance of James Franklin Bland (1799-1863). His nephew the well known architect James Franklin Fuller described the castle estate in his

autobiography as a largely self-supporting community busy with sawmill, carpenter’s shop, forge as well as farming and gardening. A fish pond existed on the water’s edge just below the castle, alternatively described as being self-replenishing with the tide or restocked from a trawler.

“The castle itself consisted of a three-storey main block with a four-storey octagonal tower rising through the centre and a two storey partly curved wing branching off in a western direction. Major renovations were carried out and a significant additional wing running southwest, overlooking the coastline was added sometime between 1895 and 1904.

“James Franklin Bland’s death in 1863 the estate passed to his son Francis Christopher, the estate slipped into decline during the time that he was absent while travelling and preaching on Christian ministry, this being during the years of land agitation in Ireland. Part of the estate was sold in the landed estates court in 1873 but ultimately the decline continued with the remainder being sold in 1891.

“It was bought in 1891 for £30,000 by Colonel Charles Wallace Warden. He had retired in 1895 as Colonel of the Middlesex Regiment (previously known as the 57th) He had seen action in the Zulu War of 1879 and on his death on 9th March 1953 in his 98th year was its oldest survivor. He also fought with the Imperial Yeomanry in the Boer War. As landlord of Derryquin he was highly unpopular with tenants and neighbours alike, his behaviour regularly mentioned in Parliament. After the burning of Derryquin Castle he retired to Buckland-tout-Saints in Devon and acquired an estate there with his payment from the burning of Derryquin.

“However in 2014 Derryquin castle rose again out of the ashes to feature in a novel by Christopher Bland chairman of the BBC who having discovered a photo of his ancestors decided to write the novel Ashes in the Wind. it interweaves the destinies of two families: the Anglo-Irish Burkes and the Catholic Irish Sullivans, beginning in 1919 with a shocking murder and the burning of the Burkes’ ancestral castle in Kerry. Childhood friends John Burke and Tomas Sullivan will find themselves on opposite sides of an armed struggle that engulfs Ireland. Only 60 years later will the triumphant and redemptive finale of this enthralling story be played out.“

Whole House Rental County Kerry:

1. Ballywilliam House, Kinsale, County Kerry – manor rental, up to 16

8 bedrooms. Minimum 14 nights stay.

2. Churchtown House, Killarney, County Kerry – luxury manor rental (sleeps 12)

Mark Bence-Jones tells us (1988):

p. 83. “(Magill/IFR) A three storey 5 bay C18 house. Doorcase with entablature on console brackets flanked by narrow windows. Fine gate piers with pineapples.” [2]

The Hidden Ireland website tells us:

“Churchtown Estate incorporates both Churchtown House and Beaufort Golf Club. The centre piece is the Georgian Churchtown House built in 1740 by Sir Rowland Blennerhassett. In 1860 James MacGillycuddy Magill bought the estate and turned it into one of the largest dairy farms of its time in the south west region.

“James’s grandson and great grandson’s closed the farm in the early nineties and with the help of golf architect Arthur Spring, developed Beaufort Golf Course which was officially opened in 1995. The golf course went through further development in 2007 when it was re-designed by Tom Mackenzie of Mackenzie Ebert – Leading International Golf Architects.

“Churchtown House mixes traditional elegance with country house charm and modern facilities. 2 large elegant reception rooms, roaring fires and quiet reading rooms add to the atmosphere. There is also a home entertainment room and games room in the basement of the house for guests to enjoy.

“The House comfortably sleeps 12 in 6 spacious bedrooms, with a selection of King or twin rooms, with 2 additional ‘pull out’ beds if needed to accommodate 14 guests. All bedrooms have private bathrooms with modern facilities. The kitchen is fully equipped with an Aga and halogen hob, modern appliances and beautiful breakfast table looking out onto the courtyard and Ireland’s highest mountain Carrauntoohil.

“The ruins of 15th century Castle Corr standing on the 15th green was designed as a square tower house. Castle Corr (Castle of the round hill) was built circa 1480 by the MacGillycuddy’s, a branch of the O’Sullivan Mór Clan. Fearing that it would have been taken by the English forces Donagh MacGillycuddy burnt the castle in 1641 but restored it in 1660. Donagh went on to become High Sheriff of Kerry in 1687.

“The castle was abandoned by Donagh’s son Denis in 1696 when he married into the Blennerhassett family in nearby Killorglin Castle. The stone of Castle Corr was taken to build the Georgian manor Churchtown House.“

3. Coolclogher House, Killarney, County Kerry – luxury vacation rental manor (up to 14 people)

The website tells us: “Coolclogher House built in 1746 is a historic manor house set on a 68 acre walled estate near Killarney on the Ring of Kerry. The house has been restored to an exceptional standard by Mary and Maurice Harnett and has spacious reception rooms, a large conservatory containing a 170 year-old specimen camellia and seven large luxurious bedrooms, each with their own bathroom and with magnificent views over the gardens and pasture to the dramatic mountains of the Killarney National Park.“

The National Inventory tells us that it was renovated in 1855 according to a design by William Atkins.

“This is an excellent base for exploring this ruggedly beautiful county and Coolclogher House specialises in vacation rental for groups of up to 16 people. It is right on the Ring of Kerry and Ross Castle and Killarney town are within walking distance while the Gap of Dunloe and Muckross House are in easy reach. It is the ideal special holiday destination for extended family groups, golfing groups or celebrating that special occasion.

“The famous Lakes of Killarney, the Killarney National Park, Muckross House and Abbey and Ross Castle are all within easy reach. Killarney is an ideal starting point on the famous Ring of Kerry, going by way of Kenmare, Parknasilla and Waterville, and returning via Cahirciveen, Glenbeigh and Killorglin, but there are also wonderful drives through Beaufort and the Gap of Dunloe, along Caragh Lake to Glencar or, for the more ambitious, a day trip to the Dingle Peninsula or the wonderful Ring of Beara. There are world famous golf courses at Waterville, Tralee and Ballybunion while boat trips on the famous Lakes of Killarney, fishing and horse riding can all be arranged.

“Situated 5 minutes from the historic town of Killarney, which boasts a number of excellent dining options and a wide variety of entertainment, this mansion house is the perfect base for a longer stay and a wonderful location for a family reunion or for celebrating a special occasion.“

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com