Note that the majority of these are private houses, not open to the public. I discovered “my bible” of big houses by Mark Bence-Jones only after I began this project of visiting historic houses that have days that they are open to the public (Section 482 properties).

This is a project I have been working on for a while, collecting pictures of houses. Enjoy! Feel free to contact me to send me better photographs if you have them! I’ll be adding letters as I go…

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My website costs €300 per year on WordPress.

€15.00

Bagenalstown House, Bagenalstown, Co Carlow

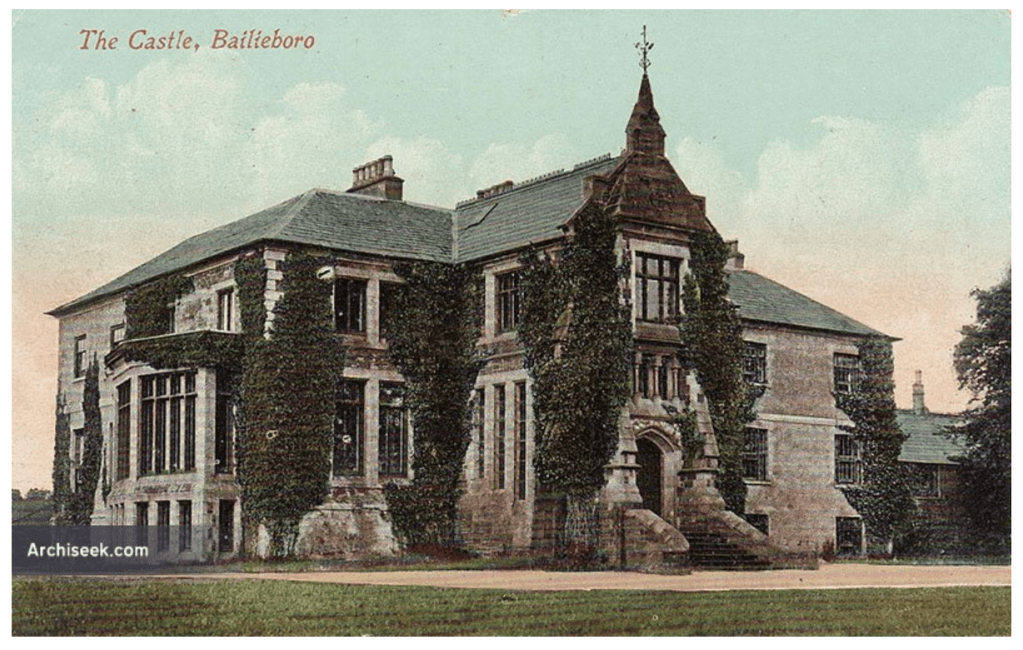

Bailieborough Castle (also known as Lisgar House or The Castle), Co Cavan – demolished

Balheary House, Swords, Co Dublin – demolished 2005

Ballaghtobin, Callan, Co Kilkenny

Ballea Castle, County Cork

This is great, I am finding new places to stay! See their website https://balleacastle.com

Ballibay House (or Ballybay), Ballibay, Co Monaghan – demolished

Ballin Temple (or Ballintemple), Tullow, Co Carlow – demolished

Ballina Park, Ashford, Co Wicklow

Ballinaboola House, Co Wexford

Ballinaboy, Clifden, Co Galway

Ballinacarriga (or Ballynacarriga), Kilworth, Co Cork

Ballinaclea (or Ballinclea), Killiney, Co Dublin – demolished

Ballinaclough House, Nenagh, Co Tipperary

Ballinacor House, Rathdrum, County Wicklow

Ballinafad (or Ballinafed), Balla, Co Mayo

They offer accommodation, see their website: http://www.ballinafadhouse.com

Ballinahina, White’s Cross, Co Cork

Ballinahown Court (or Ballynahown, Bence Jones), Count Westmeath

Ballinahy, Co Tipperary (see Anner Castle)

Ballinakill House, Waterford, Co. Waterford

Ballinalacken, County Clare (see Ballynalacken)

Ballinaminton, Clara, Co Offaly

Ballinamona, Cashel, Co Tipperary

Ballinamona Park, Waterford

Ballinamore House, Kiltimagh, Co Mayo

Ballinclea, Killiney, County Dublin

Ballinderry Park, Ballinderry Park, Kilconnell, Ballinasloe, Galway

Ballinderry, Carbury, Co Kildare

Ballindoon House (formerly Kingsborough), Derry, Co Sligo

Ballingarrane (formerly known as Summerville), Clonmel, Co. Tipperary

Ballingarry, Co. Limerick: The Turret, see The Turret

Ballinkeele, Ballymurn, Enniscorthy, Wexford – whole house rental

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/11/15/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-wexford/

Ballinlough Castle, Clonmellon, Co. Westmeath or Meath – accommodation

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-meath-leinster/

Ballinrobe, Co. Mayo

Ballinsperrig, (see Anngrove), County Cork

Ballintaggart, Colbinstown, Co. Kildare

Ballinterry House, Rathcormac, Co Cork – accommodation

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

Ballintober House, Ballinahassig, Co Cork – demolished

Ball’s Grove, Drogheda, Co Louth

Bally Ellis, County Wexford

Ballyanahan (or Ballyenahan), Co Cork

Ballyanne House, New Ross, Co Wexford

Ballyarnett, Derry, County Derry

Ballyarthur, Woodenbridge, Co Wicklow

Ballybricken, Ringaskiddy, Co Cork

Ballybroony, Co Mayo

Ballyburly, Edenderry, Co Offaly

Ballycanvan House, Waterford, Co Waterford

Ballycarron House, Golden, Co Tipperary

Ballycastle Manor House, County Antrim

Ballyclough, Kilworth, Co Cork – partly demolished

Ballyclough House, Ballysheedy, Co Limerick

Ballyconnell House, Ballyconnell, Co Cavan

Ballyconnell House, Falcarragh, Co Donegal

Ballyconra House, Ballyragget, Co. Kilkenny

Ballycross, Bridgetown, Co Wexford – demolished

Ballycullen, Askeaton, Co Limerick

Ballycurrin Castle, Co Mayo

Ballycurry, Ashford, Co Wicklow

Ballydarton, near Leighlinbridge, Co Carlow

Ballydavid, Woodstown, County Waterford

Ballydivity, Ballymoney, County Antrim

Ballydonelan Castle, Loughrea, Co Galway – ‘lost’

Ballydrain House, Drumbeg, County Antrim

Ballyduff, Thomastown, Co Kilkenny

Ballydugan House, Portaferry, County Down

Used to provide accommodation, I’m not sure if it still does.

Ballyedmond, Midleton, Co Cork – demolished after 1960.

Ballyedmond Castle, Killowen, County Down – can visit gardens.

Ballyeigan, Birr, Co Offaly

Ballyellis, Buttevant, Co Cork

Ballyfin House, Mountrath, County Laois – hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/27/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-laois-leinster/

Ballygally Castle, Larne, County Antrim – hotel

See my entry about it on my page of places to stay in County Antrim https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/03/21/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-ulster-county-antrim/

Ballygarth Castle, Julianstown, Co Meath

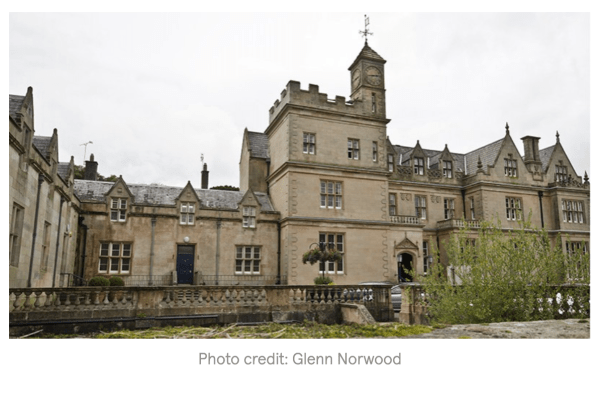

Ballygawley Park, Ballygawley, Couny Tyrone

Ballygiblin, near Mallow, Co Cork – ruin

Ballyglan, Woodstown, Co Waterford

Ballyglunin Park, Monivea, Co. Galway

Available for hire https://ballygluninpark.ie

Ballyhaise House, Ballyhaise, Co. Cavan – agricultural college

Ballyheigue Castle, near Tralee, Co Kerry – ‘lost’

Ballyhemock (or Ballyhimmock) (see Annes Grove), Co Cork

Ballyhossett, Downpatrick, County Down

Ballyin, Lismore, Co Waterford

Ballykealey, Tullow, Co Carlow – now a hotel

See my entry on places to stay in County Carlow https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/14/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-leinster-carlow/

Ballykeane, Redcross, County Wicklow

Ballykilbeg, County Down

Ballykilcavan, Stradbally, Laois – runs a brewery

Ballykilty, Quin, Co Clare

Ballykilty, Co Limerick (see Plassey House)

Ballyknockane, Ballingarry, County Limerick

Ballyknockane Lodge, Ballypatrick, Co. Tipperary

Ballylickey House, Bantry, Co Cork – hotel, Seaview House Hotel

See their website https://seaviewhousehotel.com

Ballylin House, Ferbane, Co Offaly – demolished

Ballyline House (formerly White House), Callan, Co Kilkenny

Ballylough House, Bushmills, County Antrim

See my entry about it on my page of places to stay in County Antrim https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/03/21/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-ulster-county-antrim/

Ballymack House, Cuffesgrange, Co Kilkenny

Ballymaclary House, Magilligan, Co Derry

Ballymacmoy, Killavullen, Co Cork – coach house airbnb

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

Ballymacool, Letterkenny, Co Donegal – ruin

Ballymagarvey, Balrath, Co Meath – wedding venue

See their website https://www.ballymagarvey.ie

Ballymaloe, Cloyne, Co Cork – accommodation

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

Ballymanus, Stradbally, Co Laois

Ballymartle, Kinsale, County Cork

Ballymascanion (the Cottage), Co Louth

Ballymascanlon House, Louth – hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-louth-leinster/

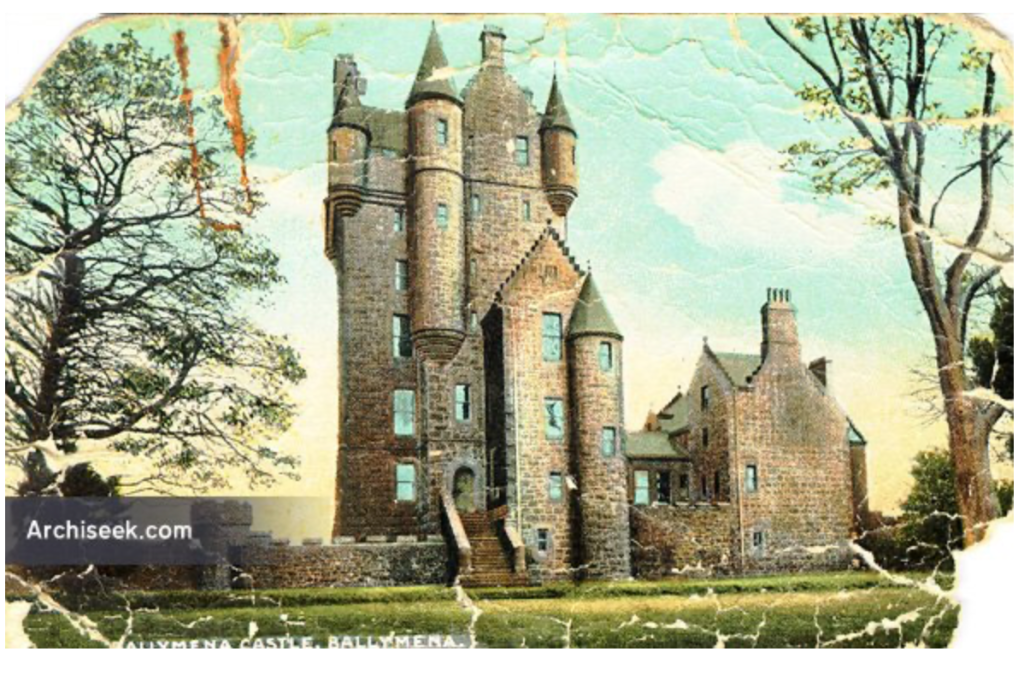

Ballymena Castle, County Antrim – demolished

Ballymoney Park, Kilbridge, County Wicklow

Ballymore, Cobh, Co Cork

Ballymore Castle, Laurencetown, Co. Galway

Ballymore, Camolin, Co Wexford – museum

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/11/15/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-wexford/

Ballymoyer House, Belleek, County Armagh – demolished

Ballynacourty, Co Limerick

Ballynacourty, Tipperary, Co Tipperary (see Ballinacourty)

Ballynacree House, Ballymoney, County Antrim – available for accommodation

Available for accommodation, https://ballynacreehouse.com

Ballynaguarde, Ballyneety, Co Limerick

Ballynahinch Castle, Connemara, Co. Galway – hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/05/31/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-galway/

Ballynahown Court, Athlone, Co Westmeath (see Ballinahown Court)

Ballynalacken Castle, Lisdoonvarna, Co Clare – hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/01/20/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-clare/

Ballynaparka, Cappoquin, Co Waterford

Ballynastragh, Gorey, Co Wexford

Ballynatray House, Glendine, Co Waterford – 482 gardens in 2023

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/12/21/ballynatray-estate-county-waterford-p36-t678-gardens-only/

Ballyneale House, Ballingarry, Co Limerick

Ballynegall, Mullingar, Co Westmeath

Ballynoe (or Newtown), Tullow, Co Carlow

Ballynoe House, Rushbrooke, Co Cork

Ballynoe, Ballingarry, Co Limerick

Ballynure, Grange Con, Co Wicklow

Ballyorney House, Enniskerry, County Wicklow

Ballyowen (formerly New Park), Cashel, Co Tipperary

Ballyquin House, Ardmore, Co Waterford

Ballyragget Grange, County Kilkenny (see The Grange)

Ballyrankin, Ferns, County Wexford

Ballysaggartmore, Lismore, Co Waterford – lost

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/26/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-munster-county-waterford/

Ballysallagh House, Johnswell, Co Kilkenny

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/06/17/ballysallagh-house-johnswell-co-kilkenny/

Ballyscullion, Bellaghy, County Derry – Ballyscullion Park

Wedding venue https://www.ballyscullionpark.com

Ballyseede Castle/ Ballyseedy, Tralee, county Kerry – section 482

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/02/ballyseede-castle-ballyseede-tralee-co-kerry/

Ballyshanduffe House (also known as The Derries), Portarlington, Co Laois

Ballyshannon House, Ballyshannon, Co Donegal

Ballyteigue Castle, Kilmore Quay, County Wexford

Ballytrent House, Broadway, Co Wexford – one wing rental

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/11/15/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-wexford/

Ballytrim, County Down

Ballyvolane, Co Cork – demolished

Ballyvolane, Castlelyons, Co Cork – Hidden Ireland accommodation

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

Ballyvonare (also called Ballinavonear), Buttevant, Co Cork

Ballywalter Park, Newtownards, Co Down

See their website https://ballywalterpark.com

Ballyward Lodge, County Down

Ballywhite House, Portaferry, County Down

Ballywillwill House, near Castlewellan, County Down

Balrath, Kells, Co Meath – section 482 and accommodation

See https://balrathcourtyard.ie

Balrath Bury, County Meath

Baltiboys, Blessington, Co Wicklow

Baltrasna, Oldcastle, Co Meath

Balyna, Moyvalley, Co Kildare – weddings (Moy Valley Hotel)

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/06/08/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kildare/

Bancroft House, County Down

Bangor Castle, County Down

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/10/06/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-down-northern-ireland/

Bannow House (originally Grange House), Bannow, Co Wexford

Bansha Castle, Bansha, Co Tipperary

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/19/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-tipperary-munster/

Bantry House & Garden, Bantry, Co. Cork – section 482, and accommodation

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/12/01/bantry-house-garden-bantry-co-cork/

Barbavilla, Collinstown, Co Westmeath

Barberstown Castle, Kildare – hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/06/08/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kildare/

Bargy Castle, Tomhaggard, Co Wexford

Barmeath Castle, Dunleer, Drogheda, Co Louth – section 482 in 2019

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/10/23/barmeath-castle-dunleer-drogheda-county-louth/

Barnabrow, Cloyne, Co Cork – accommodation and wedding venue

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

See their website https://www.barnabrowhouse.ie

Barnane, near Templemore, Co Tipperary

Barne, Clonmel, Tipperary

Baronrath House, Straffan, Co Kildare

Barons Court, Newtownstewart, County Tyrone

See their website https://barons-court.com

Baronston House (or Baronstown), Ballinacargy, Co Westmeath

Barraghcore House, Goresbridge, Co Kilkenny

Barretstown Castle, Ballymore Eustace, Kildare – children’s camp

Barretstown House, Newbridge, Co Kildare

Barrowmount, Co Kilkenny

Barrymore Lodge, Castlelyons, Co Cork

Barryscourt Castle, Carrigtwohill, Co Cork – ruin, open to public

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/01/19/office-of-public-works-properties-munster/

Baymount, Clontarf, Co Dublin (Manresa) – owned by Jesuits

Beamond House, Duleek, County Meath or Beaumond House, Duleek, Co Meath

Beardiville House, County Antrim

Bearforest, Mallow, Co Cork

Beaulieu, Drogheda, County Louth

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/03/17/beaulieu-county-louth/

Beaumond House, Duleek, Co Meath

Beauparc, Co Meath – section 482

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/07/22/beauparc-house-beau-parc-navan-co-meath/

Bective House, Bective, Co Meath

Bedford House, Listowel, Co Kerry

Beech Park, Clonsilla, Co Dublin

Beechmount, Rathkeale, Co Limerick

Beechwood Park, Nenagh, Co Tipperary

Beechy Park (formerly Bettyfield), Rathvilly, Co Carlow

Belan, Co Laois

Belan, County Kildare – ‘lost’

Belcamp House (also known as Belcamp Hutchinson), Balgriffin, County Dublin – a college

Belcamp Hall, Balgriffin, County Dublin

Belcamp Park, Balgriffin, County Dublin

Belfast Castle, County Antrim

See my entry on my page Places to visit and stay in County Antrim https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/03/21/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-ulster-county-antrim/

Belfort, Charleville, Co Cork – demolished 1958

Belgard Castle, Clondalkin, Co Dublin

Belgrove, Cobh, Co Cork – demolished 1954

Bellaghy Castle and Bawn, Bellaghy, County Derry

Bellair, Ballycumber, County Offaly

Bellamont Forest, Cootehill, Co Cavan

Bellarena, Magilligan, County Derry

Belle Isle, Lisbellaw, County Fermanagh

Belle Isle, Lorrha, Co Tipperary

Belleek Castle (or Manor, or Ballina House), Ballina, Mayo – gives tours and hotel

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/15/places-to-stay-and-visit-in-connacht-leitrim-mayo-and-sligo/

Bellegrove (also Rathdaire), Ballybrittas, Co Laois – (demolished)

Belleview, Co Cavan

Belleville Park (see Bellville) Cappoquin, County Waterford

Bellevue, Tamlaght, County Fermanagh

Bellevue, Co Galway (see Lisreaghan) – ‘lost’

Bellevue House, Slieverue, Co Kilkenny

Bellevue, Co Leitrim

Bellevue, Borrisokane, County Tipperary

Bellevue, Delgany, Co Wicklow

Belline, Piltown, Co Kilkenny

Bellinter House near Bective, County Meath – hotel and restaurant

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-meath-leinster/

Bellmont House, Mullingar, County Westmeath

Bellville Park (or Belleville, formerly Bettyville), Cappoquin, Co Waterford

Bellwood, Templemore, Co Tipperary

Belmont, Banbridge, County Down

A hotel, https://www.belmontbanbridge.co.uk

Beltrim Castle, Gortin, County Tyrone

Belvedere, Mullingar, County Westmeath– open to visitors

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/05/23/belvedere-house-gardens-and-park-county-westmeath/

Belvedere, County Down

Belvoir, Sixmilebridge, Co Clare – ruin

Belvoir Park, Newtownards, County Down – demolished 1950s

Benburb, County Tyrone: Manor House

Benekerry (or Bennekerry), near Carlow, Co Carlow

Bennett’s Court, Cobh, Co Cork – medical clinic

Benown (also known as Harmony Hall), Athlone, Co Westmeath

Benvarden House, Dervock, County Antrim

The gardens are open to the public in the summer, https://www.benvarden.co.uk

Berkeley Forest, New Ross, Co Wexford

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/11/15/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-wexford/

Bermingham House, Tuam, Co Galway

Bert (or De Burgh Manor), Athy, Co Kildare

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/06/08/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kildare/

Bessborough, Blackrock, Co Cork

Bessborough, Piltown, Co Kilkenny (Kidalton College)

Bessmount Park, Drumrutagh, Co Monaghan

Bettyfield (see Beechy Park), County Carlow

Bingfield, Crossdoney, Co Cavan

Bingham Castle, Belmullet, Co Mayo

Birchfield, Co Clare – ‘lost’

Birdstown House, Muff, Co Donegal – burnt ca 1984

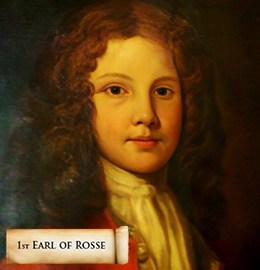

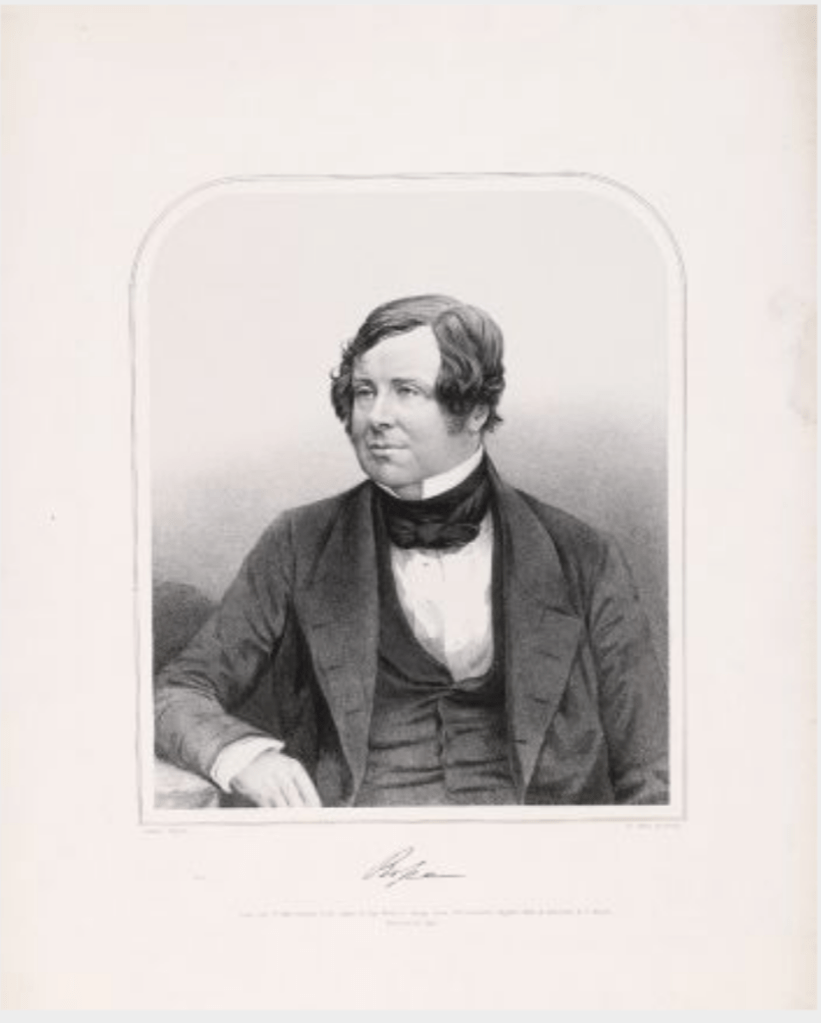

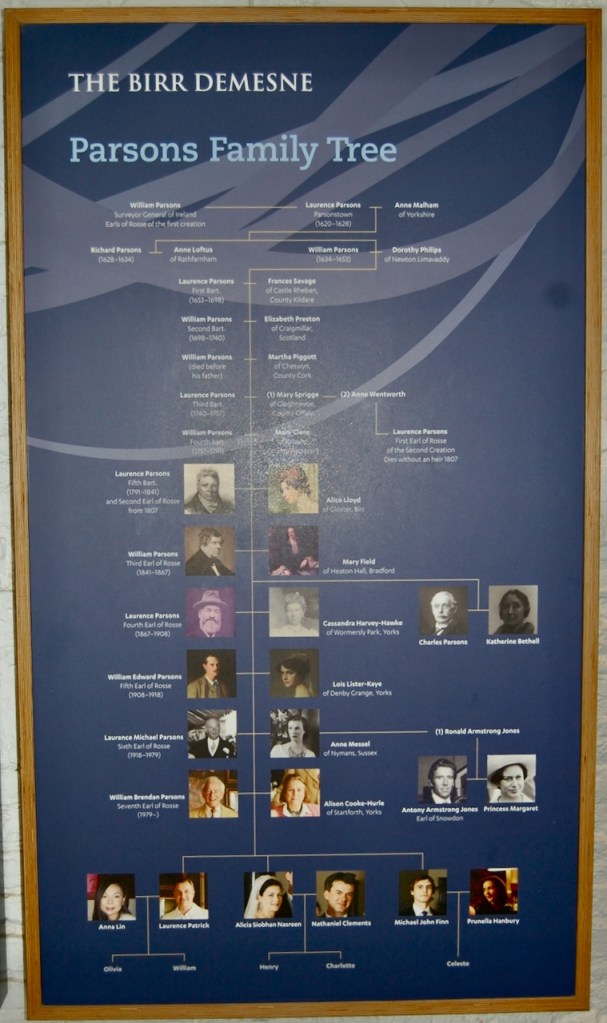

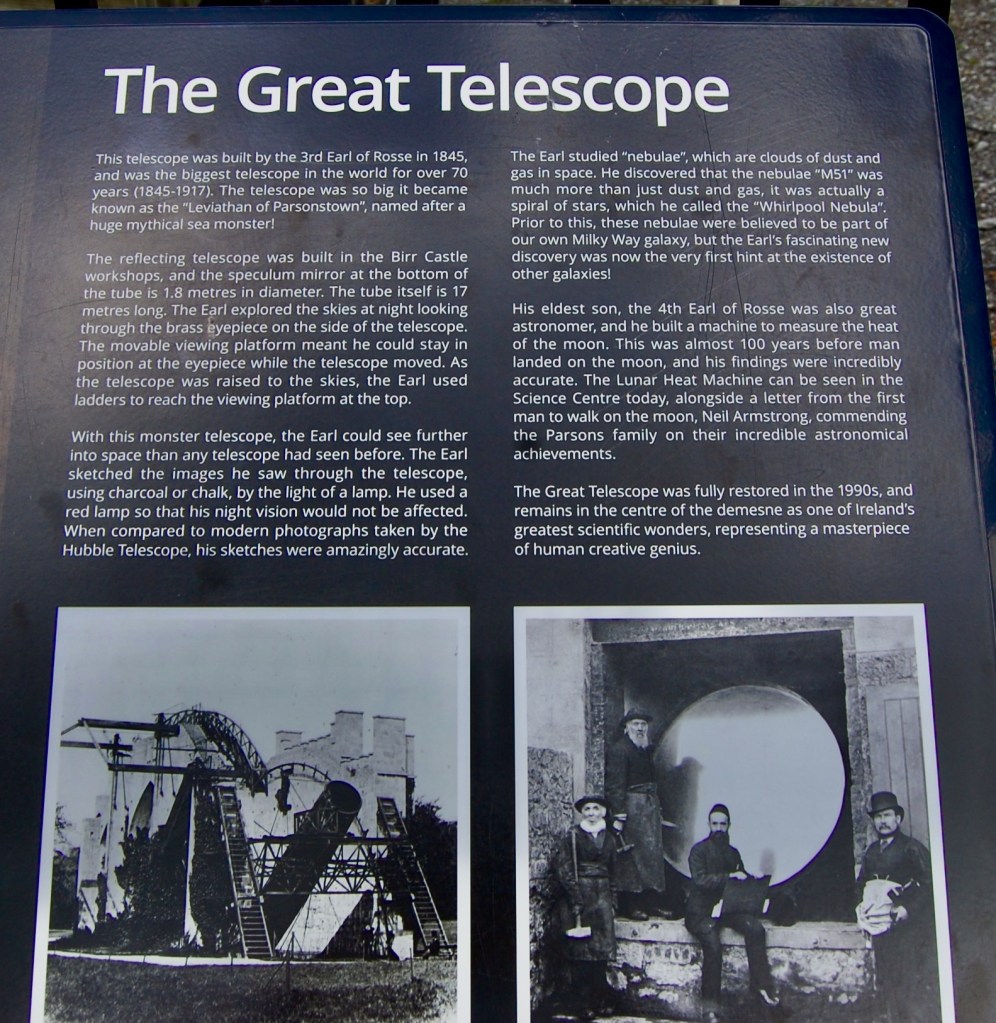

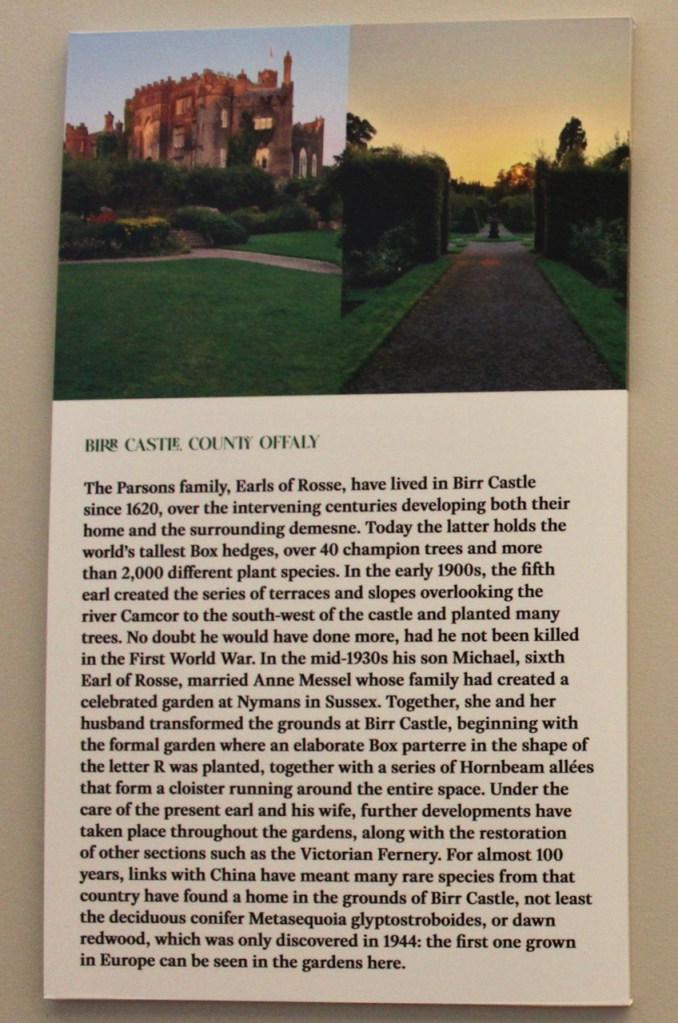

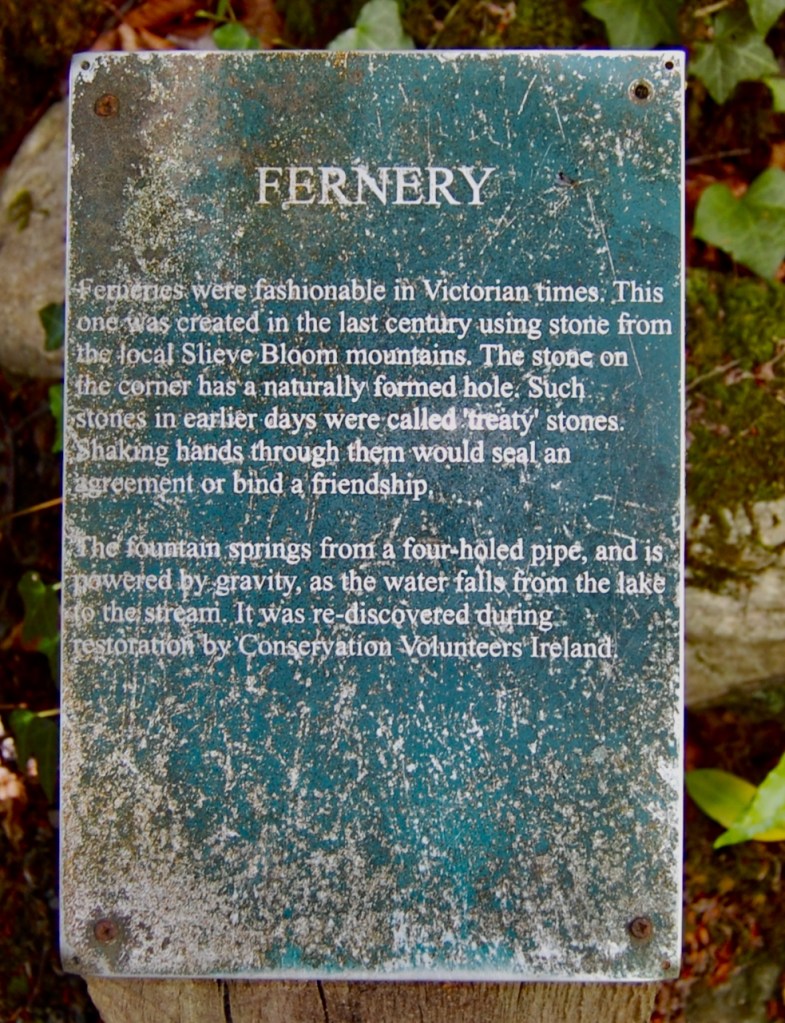

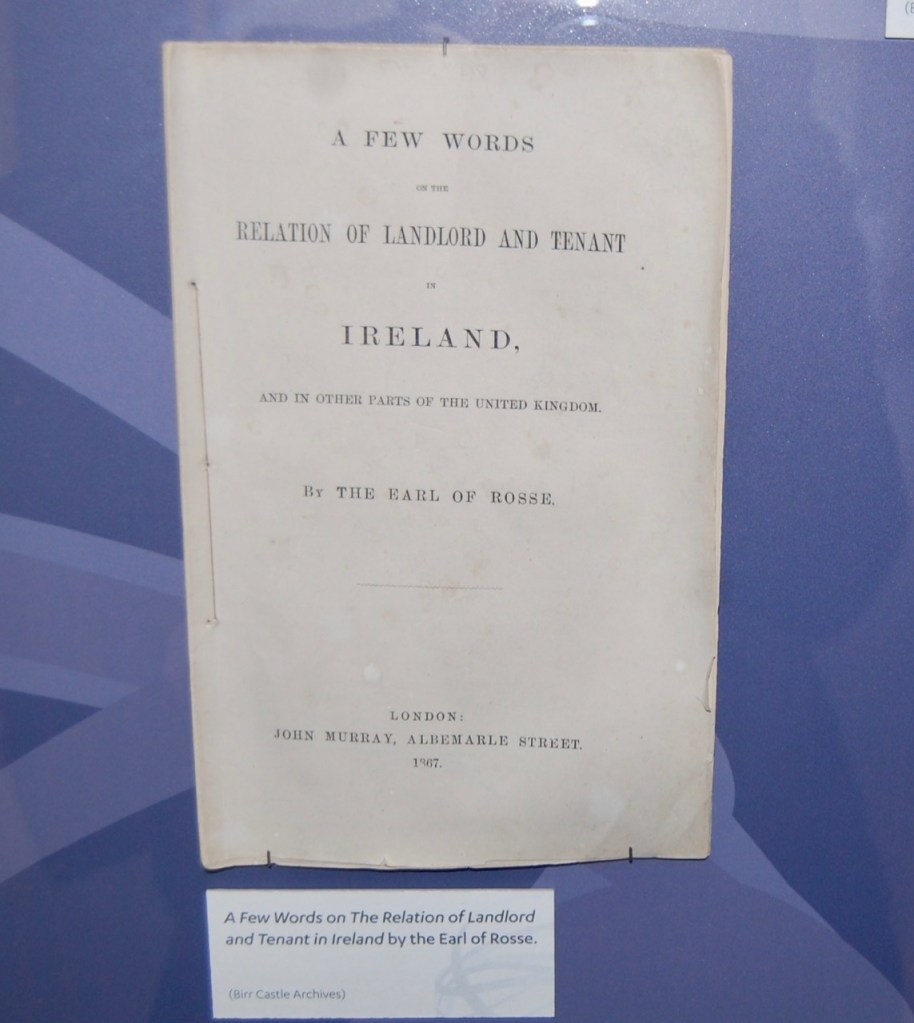

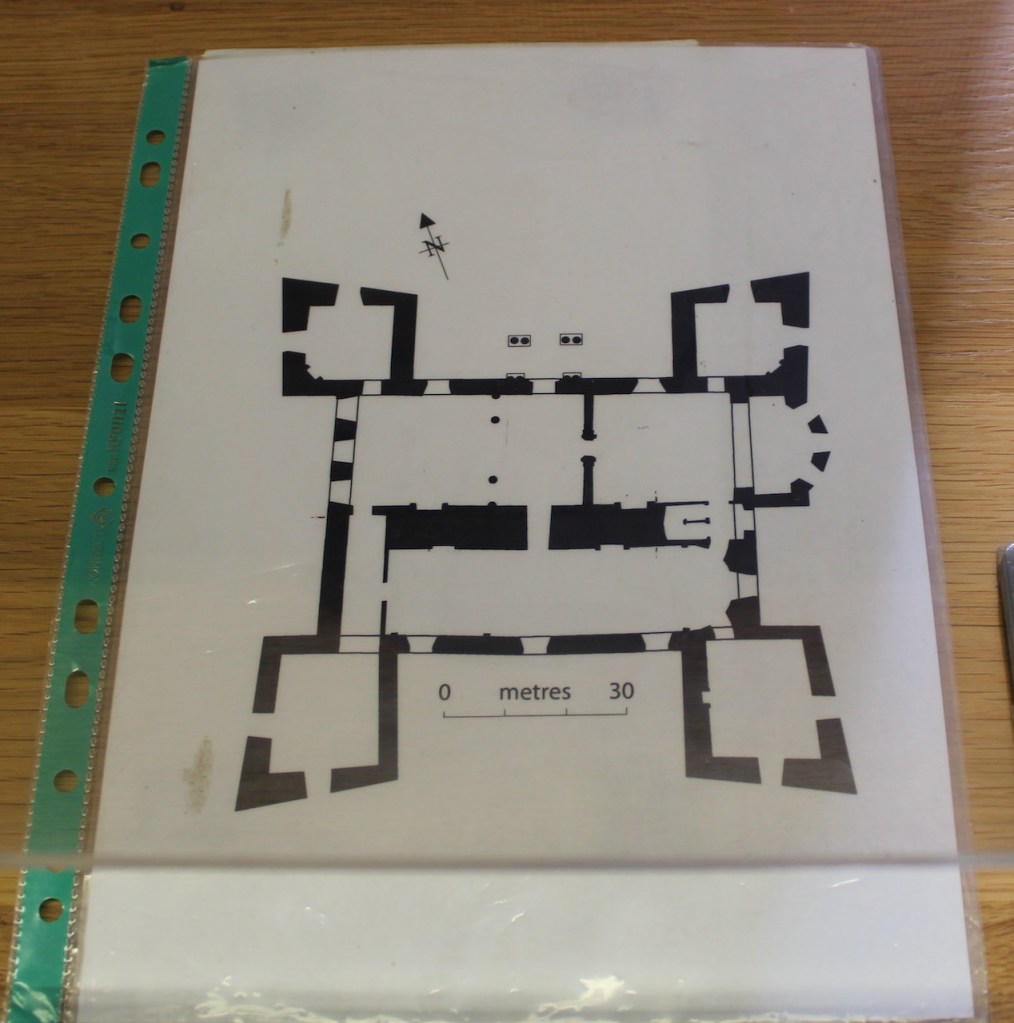

Birr Castle, Co Offaly – open to public

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/07/21/birr-castle-county-offaly-section-482/

Bishops’ Palace, (see Clarisford), Killaloe, County Clare

Bishops’ Palace, Cork, Co Cork

Bishop’s Palace, Derry, County Derry

Bishops’ Palace, Raphoe, Co Donegal – a ruin

Bishop’s Palace, Cultra, County Down

Bishop’s Palace, Dromore, County Down

Bishop’s Palace, Kilkenny, County Kilkenny

Bishopscourt, Straffan, Co Kildare

Black Castle, Navan, Co Meath

Black Hall, Termonfeckin, Co Louth

Blackhall, Clane, Co Kildare

Blackrock, Bantry (see Bantry House), Co Cork

Blackwater Castle (or Castle Widenham), Castletownroche, Co Cork

Available for hire, see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/05/17/places-to-visit-and-stay-munster-county-cork/

Blanchville, Gowran, Co Kilkenny

Coachyard accommodation, see https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kilkenny-leinster/

Blandsfort, Abbeyleix, Co Laois

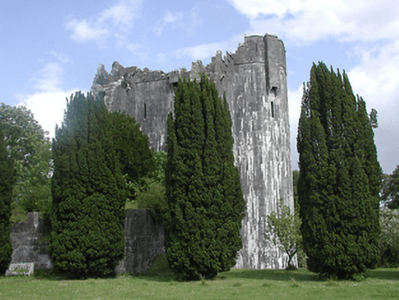

Blarney Castle, Co Cork – section 482 – open to the public

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/09/23/blarney-castle-rock-close-blarney-co-cork/

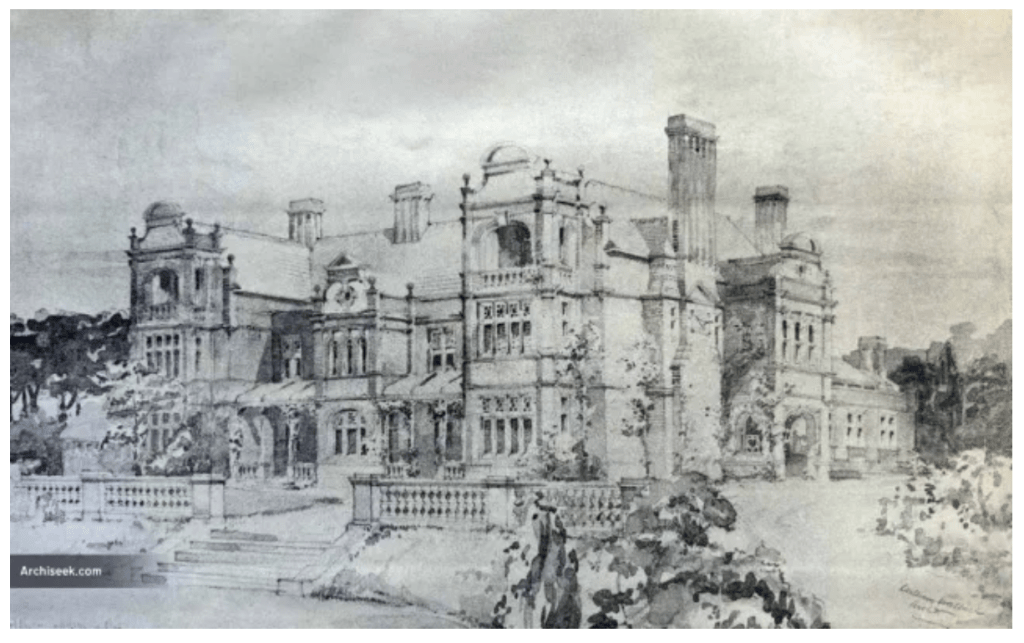

Blarney House & Gardens, Blarney, Co Cork – section 482

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/09/30/blarney-house-gardens-blarney-co-cork/

Blayney Castle, or Hope Castle, County Monaghan

Blessingbourne, Fivemiletown, County Tyrone

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/04/03/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-ulster-counties-fermanagh-monaghan-and-tyrone/

Blessington House, Co Wicklow

Bloomfield, Claremorris, Co Mayo – demolished

Bloomfield, Co Westmeath

Bloomsbury House, Kells, County Meath

Boakefield, Ballitore, Co Kildare

Bogay, Newtowncunningham, Co Donegal

Bolton Castle, Moone, Co Kildare

Bonnettstown Hall, Kilkenny, Co Kilkenny

Boomhall, County Derry

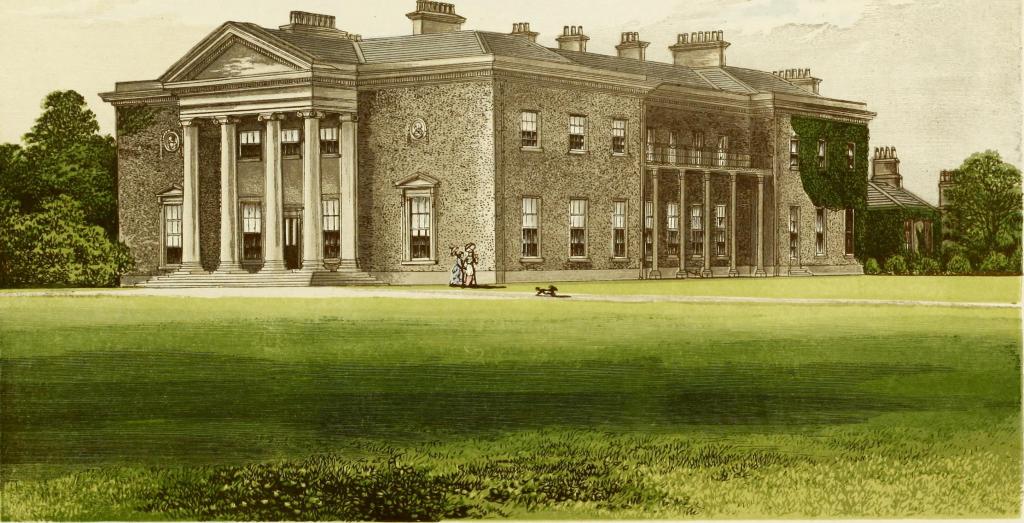

Borris House, County Carlow – section 482 in 2019

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/10/04/borris-house-county-carlow/

Borrismore House (formerly Marymount), Urlingford, Co Kilkenny

Bowen’s Court, Kildorrery, County Cork – demolished 1961

Boyne House (see Stackallan) County Meath

Boytonrath, Cashel, Co Tipperary

Bracklyn Castle, Killucan, Co Westmeath

Brade House, Leap, Co Cork

Braganstown, Castlebellingham, Co Louth

Braganza, Carlow, Co Carlow – converted into apartments

Breaghwy (or Breaffy), Castlebar, Co Mayo – hotel

Brianstown, Cloondara, Co Longford

Bridestown, Glenville, Co Cork

Bridestream House, Knocknatulla, Co Meath

Brightsfieldstown, Minane Bridge, Co Cork – demolished 1984

Brittas Castle, Clonaslee, Co Laois – ruin

Brittas, Nobber, County Meath

Brittas Castle, Thurles, Co Tipperary

Brockley Park, Stradbally, Co Laois – a ruin

Brook Lodge, Glanmire, Co Cork – new house

Brook Lodge, Halfway House, Co Waterford

Brookfield House, County Down

See https://www.abandonedni.com/single-post/brookfield-house

Brooklands, Belfast

Browne’s Hill House, Chapelstown, Co Carlow

Brownhall, Ballintra, Co Donegal

Brownlow House, Lurgan, County Armagh – National Trust

See my entry on my page https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/10/05/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-armagh-northern-ireland/

Brownsbarn, Thomastown, Co Kilkenny

Brownswood, Enniscorthy, Co Wexford

Bruree House, Bruree, County Limerick

Bullock Castle, Dalkey, Co Dublin

Buncrana Castle, Buncrana, Co Donegal

Bunowen Castle, Co Galway – ‘lost’

Bunratty Castle, Co. Clare – open to public

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/01/20/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-clare/

Burgage, Leighlinbridge, Co Carlow

Accommodation is available in the mews, www.themews.ie/

Burnchurch House, Bennettsbridge, Co Kilkenny

Burnham House, near Dingle, Co Kerry

Burntcourt Castle, or Burncourt, or Everard’s Castle, Clogheen, Co Tipperary

Burrenwood Cottage, County Down

Burton Hall, County Carlow – demolished

A three-bay single-storey over basement granite built residence remains, built c. 1725, originally wing of the larger house, which was demolished around 1930.

Burton Park (formerly Burton House), Churchtown, Co Cork – section 482 in 2019

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/02/08/burton-park-churchtown-mallow-county-cork-p51-vn8h/

Burtown House and Garden, Athy, Co Kildare – section 482 in 2019

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/06/08/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kildare/

Busherstown, Moneygall, County Offaly

Bushfield, Co Kerry (see Kilcoleman Abbey)

Bushy Park, Terenure, Co Dublin – apartments

Butlerstown Castle, Tomhaggard, Co Wexford

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/11/15/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-wexford/

Buttevant Castle, Buttevant, Co. Cork – ruin

Byblox, Doneraile, Co Cork – demolished

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €11 for the A5 size, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My website costs €300 per year on WordPress.

€15.00

Donation towards website

I receive no funding nor aid to create and maintain this website, it is a labour of love. The website hosting costs €300 annually. A generous donation would help to maintain the website.

€150.00