14 Henrietta Street is a social history museum of Dublin life, from one building’s Georgian beginnings to its tenement times. We connect the history of urban life over 300 years to the stories of the people who called this place home. The website tells us:

“Henrietta Street is the most intact collection of early to mid-18th century houses in Ireland. Work began on the street in the 1720s when houses were built as homes for Dublin’s most wealthy families. By 1911 over 850 people lived on the street, over 100 of those in one house, here at 14 Henrietta Street.“

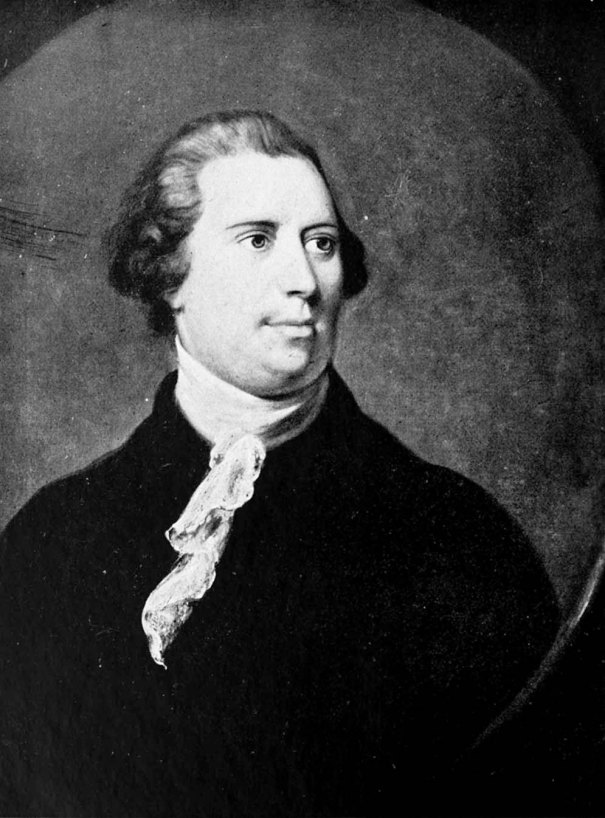

“Numbers 13-15 Henrietta Street were built in the late 1740s by Luke Gardiner. Number 14’s first occupant was The Right Honorable Richard, Lord Viscount Molesworth [1670-1758, 3rd Viscount Molesworth of Swords] and his second wife Mary Jenney Usher, who gave birth to their two daughters in the house. Subsequent residents over the late 18th century include The Right Honorable John Bowes, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Lucius O’Brien, John Hotham Bishop of Clogher, and Charles 12th Viscount Dillon [1745-1814].}

The street was named after the wife of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the time, Henrietta Crofts.

The website continues: “Number 14, like many of the houses on Henrietta Street, follows a room layout that separated its public, private and domestic functions. The house is built over five floors, with a railed-in basement, brick-vaulted cellars under the street to the front, a garden and mews to the rear, and there was originally a coach house and stable yard beyond.“

“In the main house, the principal rooms in use were located on the ground and first floors. On these floors, a sequence of three interconnecting rooms are arranged around the grand two-storey entrance hall with its cascading staircase. On the ground floor were the family rooms which consisted of a street parlour to the front, a back eating parlour, a dressing room or bed chamber for the Lord of the house, and a closet.“

“On the first floor level, the piano nobile (or noble floor), were the formal public reception rooms. A drawing room to the front is where the Lord or Lady would host visitors, along with the dining room to the back. The dressing room or bed chamber for the lady of the house, and a closet were also on this floor. Family bedrooms were located on the floor above the piano nobile, and the servants quarters were located in the attic. A second back stairs would have provided access to all floor levels for family and servants alike.“

“These grand rooms began as social spaces to display the material wealth, status and taste of its inhabitants. Dublin’s Georgian elites developed a taste for expensive decoration, fine fabrics, and furniture made from exotic materials, such as ‘walnuttree’ and mahogany.“

“After the Acts of Union were passed in Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, all power shifted to London and most politically and socially significant residents were drawn from Georgian Dublin to Regency London. Dublin and Ireland entered a period of economic decline, exacerbated by the return of soldiers and sailors at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.“

“This marked a turning point for the street – professionals moved in, and Henrietta Street was occupied by lawyers. Between 1800 and 1850 14 Henrietta Street was occupied by Peter Warren, solicitor, and John Moore, Proctor of the Prerogative Court.

“In the 19th century the rooms of the house took on a different more utilitarian tone. Fine decoration and furniture gave way to desks, quills and paperwork with the activities of commissioners, barristers, lawyers, and clerks who moved into the house.

“Family life returned to the street in the early 1860s when the Dublin Militia occupied the house until 1876, when Dublin became a Garrison town, with their barracks at Linenhall.“

“From 1850-1860 the house was the headquarters of the newly established Encumbered Estates’ Court which allowed the State to acquire and sell on insolvent estates after the Great Famine.“

“Dublin’s population swelled by about 36,000 in the years after the Great Famine, and taking advantage of the rising demand for cheap housing for the poor, landlords and their agents began to carve their Georgian townhouses into multiple dwellings for the city’s new residents.“

“In 1876 Thomas Vance purchased Number 14 and installed 19 tenement flats of one, three and four rooms. Described in an Irish Times advert from 1877:

‘To be let to respectable families in a large house, Northside, recently papered, painted and filled up with every modern sanitary improvement, gas and wc on landings, Vartry Water, drying yard and a range with oven for each tenant; a large coachhouse, or workshop with apartments, to be let at the rere. Apply to the caretaker, 14 Henrietta St.’

“In Dublin, a tenement is typically an 18th or 19th century townhouse adapted, often crudely, to house multiple families. Tenement houses existed throughout the north inner city of Dublin; on the southside around the Liberties, and near the south docklands.“In Dublin, a tenement is typically an 18th or 19th century townhouse adapted, often crudely, to house multiple families. Tenement houses existed throughout the north inner city of Dublin; on the southside around the Liberties, and near the south docklands.“

“Houses such as 14 Henrietta Street underwent significant change in use – from having been a single-family house with specific areas for masters, mistresses, servants, and children, they were now filled with families – often one family to a room – the room itself divided up into two or three smaller rooms – a kitchen, a living room, and a bedroom. Entire families crammed into small living spaces and shared an outside tap and lavatory with dozens of others in the same building.“

“By 1911 number 14 was filled with 100 people while over 850 lived on the street. The census showed that it was a hive of industry – there were milliners, a dressmaker (tailoress!), French polishers, and bookbinders living and possibly working in the house.“

“With the establishment of the new state, improvements to housing conditions in Dublin became a priority. In 1931 Dublin Corporation appointed its first city architect Herbert Simms to improve the standard of housing in the city. Simms and his team created new communities outside the city centre, amidst greenery and fresh air, this was the dawn of the suburbs. The development of these new communities signalled the end of tenement life in Dublin.“

“The last tenement residents of number 14 left in the late 1970s by which time the building was virtually abandoned by its owners after the basement and third floor (attic) had already become uninhabitable. During this period of neglect the processes of decay accelerated, leading to the rotting of structural timbers, loss of decorative plasterwork, and vandalism, leaving the house close to imminent collapse.

Dublin City Council began a process to acquire the house in 2000, and as a result of the Henrietta Street Conservation Plan and embarked on a 10-year long journey to purchase, rescue, stabilise and conserve the house, preserving it for generations to come.

In September 2018 14 Henrietta Street opened to the public.“

I am a fan of Mary Wollestonecraft, and am delighted with the connection to the house next to this address, 15 Henrietta Street, which was owned by the King family.

“In 1786, on the far side of the wall in number 15, Mary Wollstonecraft was governess to Lord and Lady Kingsborough’s children. As tutor to Margaret King she instilled a wish for equal rights and republican ideals in her charge. She had an aspiration to be treated equally in a society where she was expected to fend for herself as most ladies of the ascendancy had to when suitors were not to be had or dowries were scarce. Governesses to wealthy families held a precarious middle ground between servant and family friend. In 1792 she would publish an important feminist treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Women.”

“Wollstonecraft gives us a look at a Dublin where women were expected to abide by what she regarded as oppressive social rules: “Dublin has not the advantages which result from residing in London; everyone’s conduct is canvassed, and the least deviation from a ridiculous rule of propriety… would endanger their precarious existence”.”

See also the wonderfully informative book, The Best Address in Town: Henrietta Street, Dublin and its First Residents 1720-80 by Melanie Hayes, published by Four Courts Press, Dublin 8, 2020.