https://www.malahidecastleandgardens.ie

The castle is described in the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage as a five bay three storey over basement medieval mansion from 1450, renovated and extended around 1650, and again partly rebuilt and extended in 1770 with single-bay three-storey Georgian Gothic style circular towers added at each end of the front elevation. It was further extensively renovated in 1990. It is open to the public.

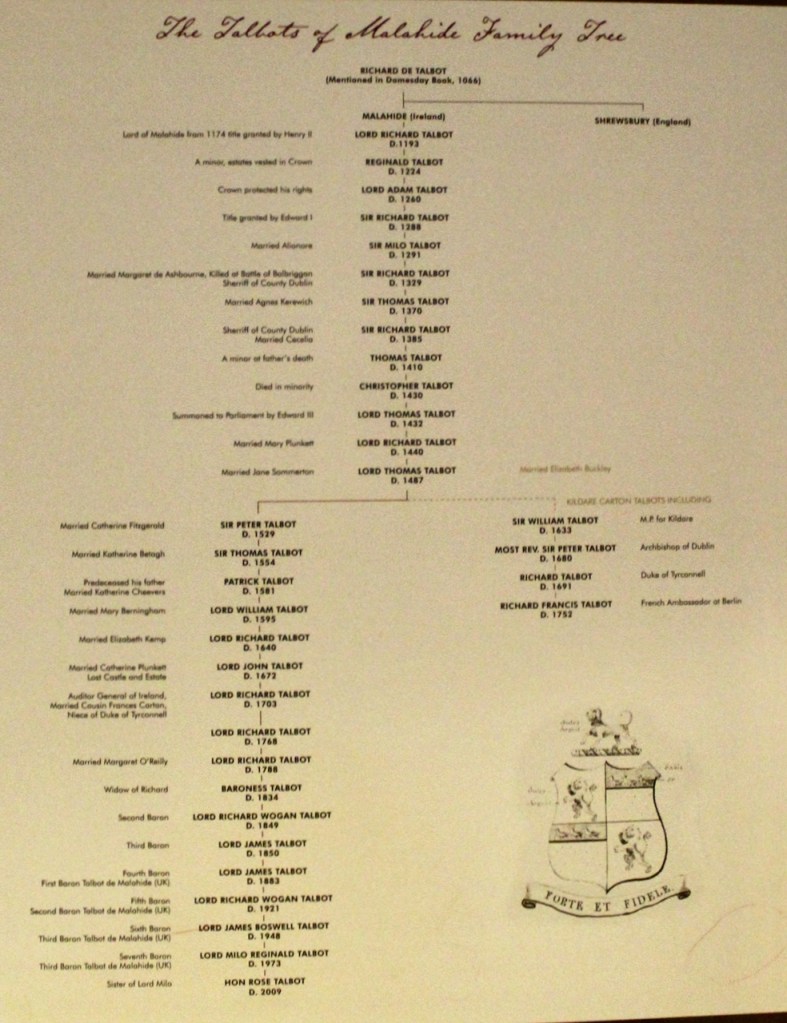

In 1185, Richard Talbot, who had accompanied King Henry II of England to Ireland in 1174, was granted the land and harbour of Malahide. [2] Talbots remained living at the site of Malahide Castle for the next nearly 800 years, from 1185 until 1976, with the exception of a few years during Oliver Cromwell’s time as Lord Protectorate.

I visited again recently so though I have published about the castle before, I am adding to it today. Unfortunately I seem to have lost the first two pages of the notes I took, so apologies to our very informative tour guide!

The Malahide Castle website tells us :

“The original stronghold built on the lands was a wooden fortress but this was eventually superseded by a stone structure on the site of the current Malahide Castle. Over the centuries, rooms and fortifications were added, modified and strengthened until the castle took on its current form.” [3]

The first stone castle was probably built around the end of the fifteenth century. It was a simple rectangular building of two storeys. The ground floor contained the kitchen and servants quarters and the first floor the family quarters and a great hall.

Mark Bence-Jones describes it in his Guide to Irish Country Houses:

p. 198. “(Talbot de Malahide, b/PB) The most distinguished of all Irish castles, probably in continuous occupation by the same family for longer than any other house in Ireland. It also contains the only surviving medieval great hall in Ireland to keep its original form and remain in domestic use – at any case, until recently.” [4]

Another castle that has been in nearly continuous occupation by the same family since the time of the Norman invasion and of King Henry II of England is Dunsany in County Meath – which was also occupied by a Cromwellian during the time of the Protectorate. Dunsany is a Revenue Section 482 property and it can be visited on certain dates during the year, and it is still occupied by the Plunkett family. (I haven’t published an entry about it as the family asked me not to.) Another, whose entry I will be adding to soon after my Heritage Week visit, is Howth Castle in Dublin, built by the St. Lawrence’s, or an earlier version of it, after the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, and which was only sold by the family a few years ago.

The Dunsany Plunkett and the Talbot families intermarried. Matilda Plunket (d. 1482), daughter of Christopher Plunket of both Dunsany and Killeen, sister of Christopher Plunket 1st Baron of Dunsany (d. 1467), married Richard Talbot of Malahide (b. 1418).

Matilda Plunket’s first husband, Walter Hussey, Baron of Galtrim, was killed in a battle on their wedding day! The couple were married on Whit Monday 1429, but within a few hours the bridegroom was murdered in a skirmish at Balbriggan, County Dublin. In the Meath History Hub, Noel French tells us that Lord Galtrim supposely wanders through Malahide Castle at night pointing to the spear wound in his side and uttering dreadful groans. It is said he haunts the Castle to show his resentment towards his young bride, who married his rival immediately after he had given up his life in defence of her honour and happiness.

Matilda married Richard Talbot in 1430. When Richard died she married a third time, to John Cornwallis, who held the office of Chief Baron of the Exchequer of Ireland. She moved back to Malahide Castle when widowed, running the household and overseeing major extensions to the castle. The Archiseek website tells us that the castle was notably enlarged in the reign of Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483). Matilda is buried in the old abbey next to Malahide Castle.

Richard and Matilda’s son Thomas Talbot (d. 1487) held an office created for him by King Edward IV in 1475, called Hereditary Lord High Admiral of Malahide and the Adjacent Seas. With this title he was awarded dues from customs, which would have been lucrative.

Thomas’s son John Talbot lived in Dardistown Castle in County Meath, another Section 482 property which can be visited. https://irishhistorichouses.com/2019/07/19/dardistown-castle-county-meath/

Another son, Peter Talbot (d. 1528) married Catherine Fitzgerald, an illegitimate daughter of Gerald Fitzgerald 8th Earl of Kildare.

The Gothic windows over the entrance door are the windows of the oldest remaining part of the castle, the Oak Room. The windows themselves were only added in the 1820s, when the Oak Room was enlarged to the south by Colonel Richard Wogan Talbot, 2nd Baron, when he added on the Entrance Porch and the two small squared towers. Originally, there was no entrance on the south side, but a shell-lined grotto.

The Oak Room would have been the main room in the early stone castle.

The oak room is lined with oak panelling, elaborately carved. The carvings would have originally been part of older furniture. The panelling would have made the room warmer than having bare stone walls or limewash. The panels were painted white to make the room brighter as the windows would have been small to keep out the cold and to protect against invaders.

The Talbot crest features a lion and a dog, symbolising strength and loyalty. In the entrance courtyard to the castle, Talbot dogs sit on the pillars.

The website of the Malahide Historical Society tells us that in 1641 John Talbot (d. 1671) succeeded his father Richard to the lordship of the Talbot estates in Malahide, Garristown and Castlering (Co. Louth).

During the uprising of 1641, Talbot tried to remain neutral, although as Catholics, many of his relatives rebelled. The Malahide Heritage website tells us:

“The Duke of Ormonde, on behalf of the Lords Chief Justices, garrisoned Malahide Castle but desisted from laying waste the farmland and village. The 500 acres about the castle were very productive and Talbot was supplying the garrison and Dublin with grain and vegetables at a time when the authorities were concerned with a very severe food shortage. Nevertheless, John was indicted for treason in February 1642, outlawed and his estates at Malahide, Garristown and Castlering declared forfeited. However, he managed to rent back his own castle and estate for a further decade.“

In 1653 Myles Corbett, Commissioner of Affairs in for Oliver Cromwell in Ireland, fleeing from an outbreak of plague in Dublin, ousted the family and obtained a seven-year lease on the castle.

When Charles II was restored to the throne, Myles Corbett was executed for his role in signing the death warrant of King Charles I.

The castle was restored to the Talbots after Corbet’s death.

John Talbot married Catherine Plunkett, daughter of Lucas 1st Earl of Fingall, of Killeen Castle, and Susannah Brabazon daughter of Edward Brabazon, 1st Lord Brabazon and Baron of Ardee (the Brabazons still live in Killruddery in County Wicklow).

According to tradition, Mark Bence-Jones tells us, the carving of the Coronation of the Virgin above the fireplace of the Oak Room miraculously disappeared when the castle was occupied Myles Corbett and reappeared when the Talbots returned after the Restoration. This would have been a Catholic tale, as Protestants do not believe in the virgin birth and would not venerate Mary the mother of Jesus in the way that Catholics do. The carving is seventeenth century Flemish.

Behind the carved panels on the wall to the right hand side of the fireplace is a door that acted as an escape route for Catholic priests when Catholic mass was held in this room.

When he returned to Ireland after Corbet left Malahide, Talbot acted as agent for Irish Catholics attempting to recover confiscated estates. He regained title to Malahide but he lost the customs of the port of Malahide, all his land in Castlering and most of the Garristown land, amounting to 2,716 acres in all or two-thirds of what he inherited in 1640.

The other ancient room in the castle is the Great Hall, which dates to 1475. The room has carved wooden corbel heads of King Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483), which are original. Here, Talbots would have presided over a medieval court, a place of banquets, feasting and music, with its minstrals gallery. The minstrels would have been kept away from the family for health reasons, as they might have carried disease and infection.

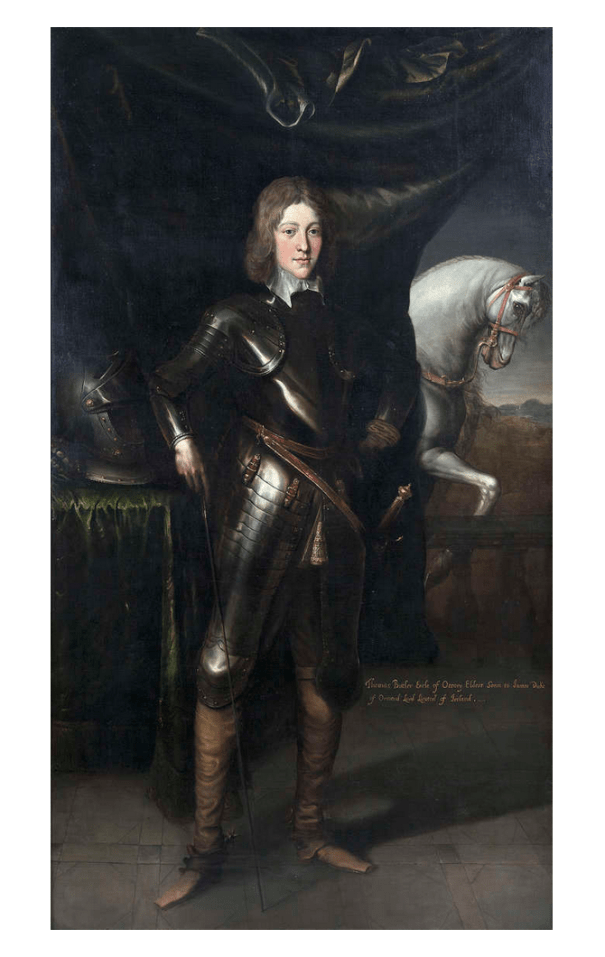

The Great Hall has an important collection of Jacobite portraits. Jacobites were supporters of King James II, as opposed to William of Orange. The portraits belonged to the Talbots and were acquired by the National Gallery and are now on loan to the castle.

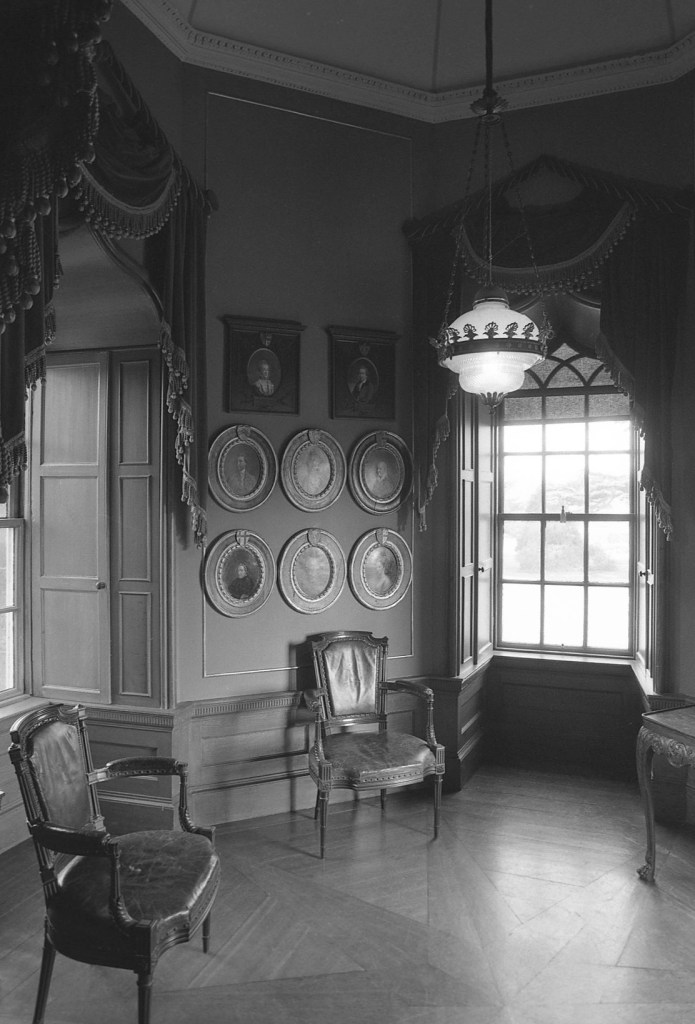

Richard Wogan Talbot (1766-1849) 2nd Baron Talbot extensively remodelled the Great Hall in 1825 in a neo-gothic revival style. Also, as you can see in my photographs, the ceiling has more wooden beams than in the 1976 photographs: the room was conserved in 2022 to honour its history.

Work on the Great Hall was carried out under the direction of conservation architects Blackwood Associates Architects. Over €500,000 was invested by Fingal County Council. Work was done to the external fabric of the building, including upgrading the roof and rainwater goods. Internally, the rafters of the great hall were restored as well as the minstrels’ gallery.

Conservation of the 19th century windows and fireplaces also took place. Studying the photographs, the windows appear to have been moved from the right hand side when facing the minstrals gallery, to the left hand wall! In fact a room seems to have disappeared from the Dublin City Library and Archives 1976 photograph above.

I was greatly interested in the portraits and would love to return to learn more about them and their sitters.

I have not yet identified the man who currently takes pride of place over the chimneypiece between the two windows.

An exerpt from J. Stirling Coyne and N.P. Willis’s The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland, 1841, describes the portrait collection at Malahide Castle, writing that there were portraits of Charles I and his wife by Van Dyke and of James II and his queen by Peter Lely.

John Talbot (d. 1671) and Catherine Plunkett’s son Richard (1638-1703) married Frances Talbot (d. 1718) daughter of Robert Talbot (d. 1670) 2nd Baronet Talbot, of Carton, Co. Kildare. Frances’s father played a leading role in the Catholic Confederacy of the 1640s.

The Talbot family played a leading role at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690: it is said 14 members of the Talbot family had breakfast together in the great hall on the morning of the battle, but only one of the 14 cousins returned to Malahide when the battle was over. They fought on the side of James II.

Richard’s wife Frances was a niece of Richard Talbot, 1st Duke of Tyrconnell (1630-1691). The Duke of Tyrconnell was a close companion of James, Duke of York, who later became King James II. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tell us:

“At the battle of the Boyne on 1 July the greater part of the Jacobite army was diverted upstream as a result of a Williamite ruse, leaving Tyrconnell in command of 8,000 men at Oldbridge, where the battle was fought and lost, despite fierce resistance, especially from Tyrconnell’s cavalry. Immediately after the battle both Lauzun and Tyrconnell advised James to leave for France.“

Richard Talbot (1630-1691), Duke of Tyrconnell’s portrait takes centre stage on the back wall of the Great Hall.

I’m not sure what role Richard of Malahide played in battles in Ireland, but he was Auditor-General of Ireland in 1688, when the Duke of Tyrconnell was Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Richard of Malahide and his sons survived the change in monarchy and although the Earl of Tyrconnell and his brother, Frances Talbot’s father the 2nd Baronet of Carton, were attainted, Richard managed to keep his estate of Malahide.

The library wing dates to the seventeenth century and is hung with eighteenth century leather wall hangings.

Richard’s son John (1668-1739) married Frances Wogan, daughter of Colonel Nicholas Wogan of Rathcoffey, County Kildare. The Wogans had also been a Jacobite family.

The family continued to intermarry with prominent Irish Catholic families: John and Frances née Wogan’s son Richard (d. 1788) married Margaret O’Reilly, daughter of James O’Reilly of Ballinlough Castle and of Barbara Nugent, another Catholic family. Archiseek tells us that the family remained Roman Catholic until 1774. At this time Richard officially converted to Protestantism, but our tour guide pondered rhetorically “but did he really?” His wife Margaret did not convert.

Richard raised a company of military volunteers. The Malahide heritage site tells us:

“Early in November 1779, the anniversary of the birth of William III and of his landing in England, one hundred and fifty of Captain Talbot’s men joined up with other north side Volunteers and all nine hundred marched through the city to College Green led by the Duke of Leinster. There, in company with south side Volunteers, they called for Free Trade between Ireland and England, firing off their muskets and discharging small cannon. The scene was recorded by the English painter Francis Wheatley in his well known canvas. Talbot’s Volunteers later formed the nucleus of an officially recognised regiment of Fencibles, renamed the 106th Regiment of Foot with Richard as their colonel. They proved unruly and mutinous and were disbanded in 1783 but not before they had cost Talbot a great deal of expense.“

A fire in the castle in 1760 destroyed a great hall that dated from the early 16th or 17th century. The room had been divided into four smaller rooms by hanging tapestries from the ceiling to form walls. Richard and Margaret had a new Georgian Gothic wing built, which added two slender round towers. Part of the castle was reconfigured with the new wing, to create two magnificent drawing rooms with rococo plasterwork which may be by or is certainly in the style of Robert West.

Mark Bence-Jones suggest that the work at Malahide Castle was probably done by amateur architect Thomas Wogan Browne, who may also have carried out work for Hugh O’Reilly (1741-1821) of Ballinlough Castle in County Westmeath, Margaret’s brother.

Thomas Wogan Browne (d. 1812) of Castle Brown in County Kildare, which is now the home of the school Clongowes Woods College, was a cousin of Richard. Richard Talbot’s mother was Frances Wogan, daughter of Nicholas Wogan of Castle Browne and his wife Rose O’Neill, and her sister Catherine married Michael Browne, and was the mother of Thomas Wogan Browne. [6]

The Dictionary of Irish Biograph tells us that, like Richard Talbot, Wogan Browne was brought up a Catholic but at about the time of his marriage conformed to the Protestant church (October 1785), which enabled him to play a part in local life and politics closed to him as a Catholic.

Ballinlough Castle is available for hire! See my entry about Places to Visit and Stay in County Meath https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/28/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-meath-leinster/

The pair of “Malahide Orange” painted drawing rooms which contain rococo plasterwork in the manner of Robert West and the Dublin school also have decorative doorcases and marble fireplaces and are now filled with portraits and paintings.

West, Robert (d. 1790), stuccodore and Dublin property developer, was probably born in Dublin c. 1720-1730. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that he was established in his trade by c.1750. His brother John was also a plasterer and builder. The Dictionary of Irish Biography entry states:

“West is often confused with Robert West (d. 1770), artist and draughtsman, who lived in Dublin at the same time and was a teacher of applied arts such as stucco design as well as life drawing. Though there is no evidence that the two men were blood relatives, they would almost certainly have known of each other’s work. Continental prints, showing ceiling designs by artists such as Bérain, Pineau, and Boucher, were commonly circulated among craftsmen and students in Dublin during the 1750s and 60s. Robert West the artist may have provided inspiration for some of the motifs (such as birds, swags, and musical instruments) used by West the stuccodore. The design and fixing of plasterwork was a complex collaborative venture involving many hands, and it is rarely possible to attribute plasterwork designs to a single artist. It is known that Robert worked alongside his brother John West and he would have required a team of assistants.“

“Robert was a property developer as well as a stuccodore, which provided a ready-made market for his team of plaster workers. In 1757 he leased two adjacent plots on what is now Lower Dominick St. The surviving plaster work in number 20, which is attributed to West and his circle, is among the most daring rococo plasterwork to be found anywhere in Ireland. Menacing birds perch on pedestals, and naturalistic busts of girls, sea-pieces, and bowls of flowers are sculpted with great sensitivity. West is associated with the plasterwork in about ten town houses in Dublin such as 4 and 5 Rutland (latterly Parnell) Square and 86 St Stephen’s Green. All of these interiors date from c.1756 to 1765. West is not connected to any plasterwork between 1765 and his death in 1790.“

“The West circle of stuccodores was instrumental in encouraging imaginative rococo plasterwork in Ireland during the 1750s and 1760s. West was a magpie in terms of style and deployed elements of the chinoiserie (winged dragons and ho-ho birds) alongside the more conventional swirling acanthus leaves commonly found on contemporary continental prints. Indeed, this eclectic mix can be seen in many Dublin town houses and in country houses as far afield as Florence Court, Co. Fermanagh.“

Mark Bence-Jones continues: “The doorway between the two rooms has on one side a doorcase with a broken pediment on Ionic columns. The walls of the two drawing rooms are painted a subtle shade of orange, which makes a perfect background to the pictures in their gilt frames.

“Opening off each of the two drawing rooms is a charming little turret room. A third round tower was subsequently added at the corner of the hall range, balancing one of C18 towers at the opposite side of the entrance front; and in early C19, an addition was built in the centre of this front, with two wide mullioned windows windows above an entrance door; forming an extension to the Oak Room and providing an entrance hall below it.”

The Malahide history website tells us that to generate employment for his tenants, beginning in 1782 Richard Talbot built a five-storey cotton mill, generating energy from a large water wheel. He wanted to construct a canal from Malahide into county Meath, from which he could obtain a toll, and obtained parliamentary approval, but died just as work commenced in 1788, so it wasn’t built. [6]

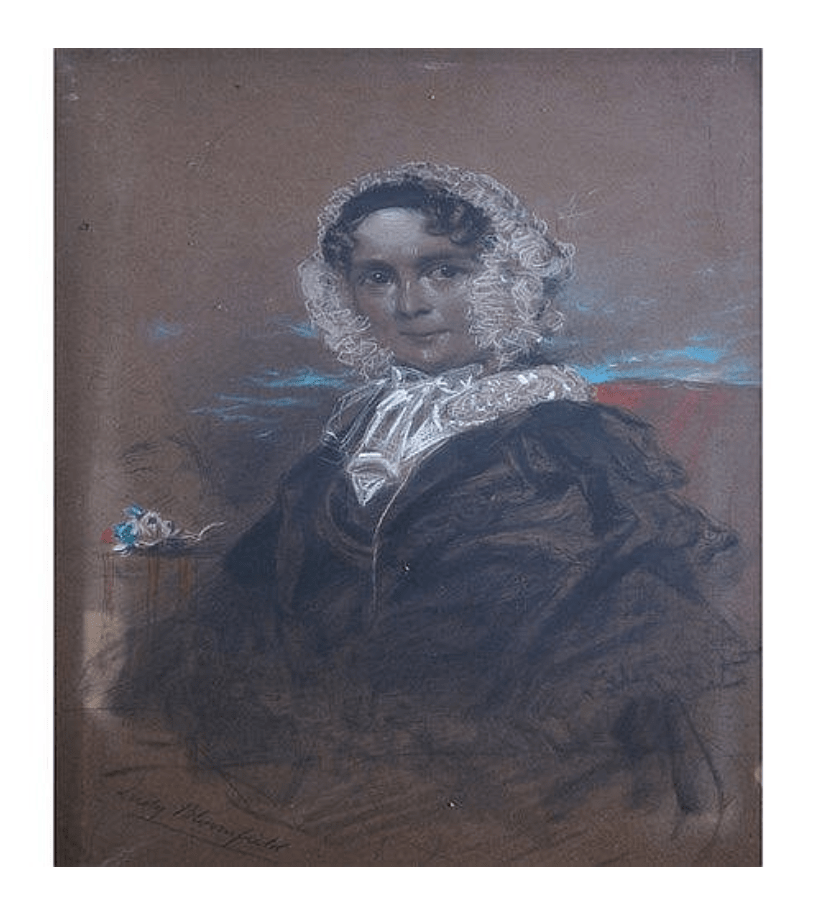

Richard’s widow Margaret was created Baroness Talbot in 1931 at the age of 86. This could be due to her husband’s work, and also her family connections. She was related by marriage to the influential George Temple Grenville, later to become the Marquess of Buckingham, who was twice Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He married Mary Nugent, daughter of Robert Craggs-Nugent (né Nugent), 1st Earl Nugent. His patronage would be of considerable benefit to Margaret and her offspring. Due to this creation, her sons then became Barons.

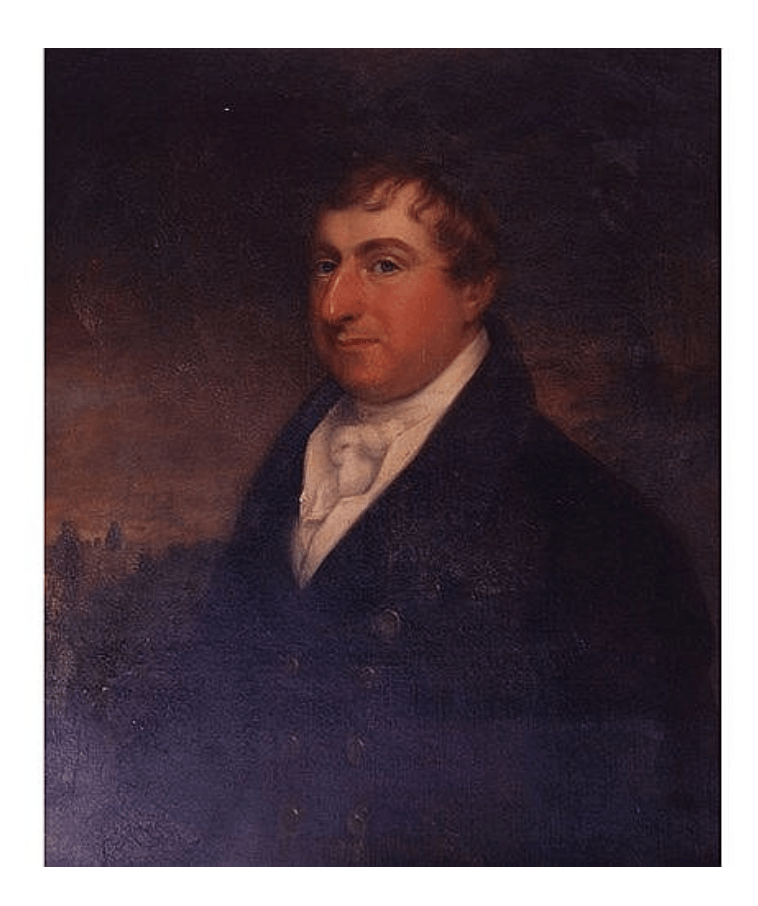

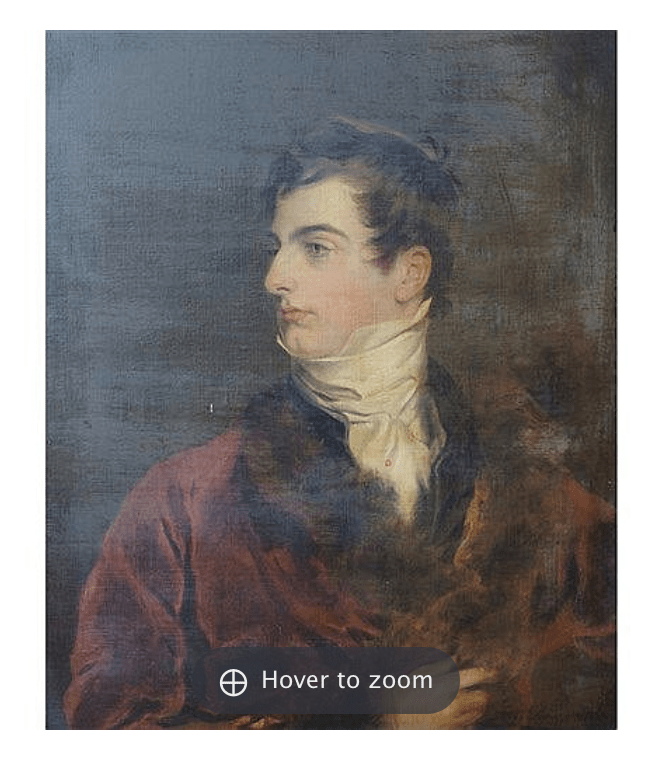

Her son Richard Wogan Talbot (1766-1849) became 2nd Baron Talbot of Malahide in 1834 when his mother died. He held the office of Member of Parliament (Whig) for County Dublin between 1807 and 1830. The Malahide Heritage Site tells us that he carried out extensive repairs and improvements to Malahide Castle and let it for the summer of 1825 to the Lord Lieutenant, the Marquesss of Wellesley (the Duke of Wellington’s eldest brother Richard).

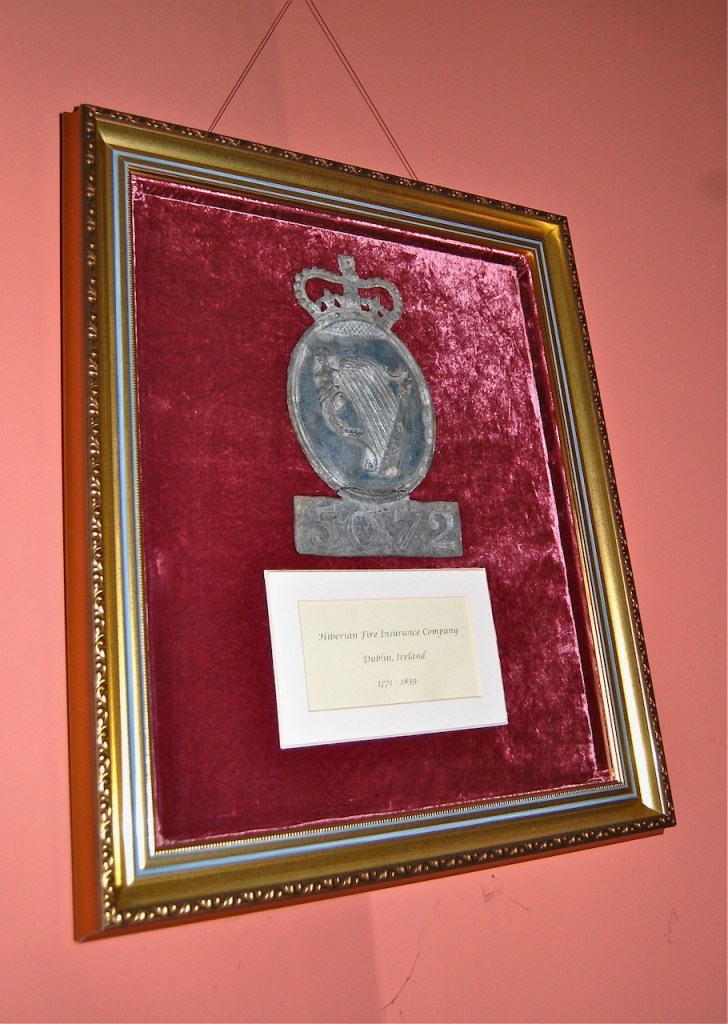

When there was a dire shortage of coinage in 1803, Richard Wogan Talbot set up a bank in Malahide with authority to issue small denomination notes. He became an early director of the Provincial Bank of Ireland which many years later amalgamated with the Munster & Leinster Bank and the Royal Bank of Ireland to form the now existing Allied Irish Bank.

He also sought to improve the farmland on Lambay and retired there for extended periods on several occasions, so it is apt that later owners of Lambay are of the Barings bank family. (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/01/03/lambay-castle-lambay-island-malahide-co-dublin-section-482-tourist-accommodation/ )

Richard Wogan Talbot was elected to Westminster in 1806 and continued there until he retired in 1830. He was a supporter of Catholic Emancipation.

He was created Baron Furnival of Malahide in 1839 in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. He married firstly Catherine Malpas (d. c.1800) of Chapelizod and Rochestown, Co. Dublin, by whom he had two children. In 1806 he married Margaret Sayers, daughter of Andrew Sayers of Drogheda. He lived beyond his limited means throughout most of his life and was supported by his mother, Margaret. [7]

His son predeceased him, so the baronetcy passed to his brother, James Talbot (1767-1850).

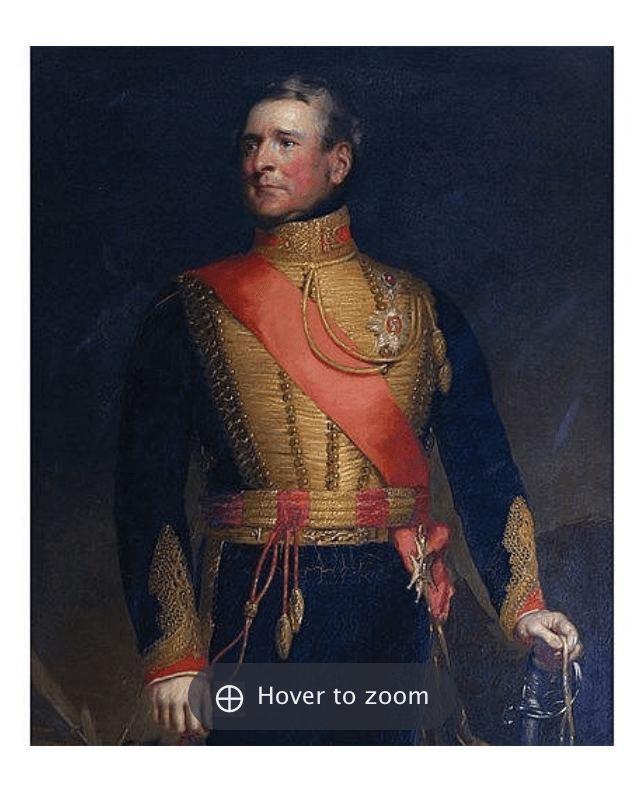

The Dictionary of Irish Biography has an extensive entry for James Talbot (1767-1850) 3rd Baron of Malahide, who was a diplomat and spy! From 1796 until he retired in 1803 he engaged in highly sensitive and covert activities mainly in France and Switzerland. In 1804 he married Anne Sarah Rodbard of Somerset with whom he had seven sons and five daughters. The family lived in France and Italy for about thirteen years before returning to his wife’s family home in Somerset. On the death of his brother Richard in October 1849 he became 3rd Baron Talbot. However, he was too infirm to travel to Malahide and he died in December 1850, aged 83. [see 7]

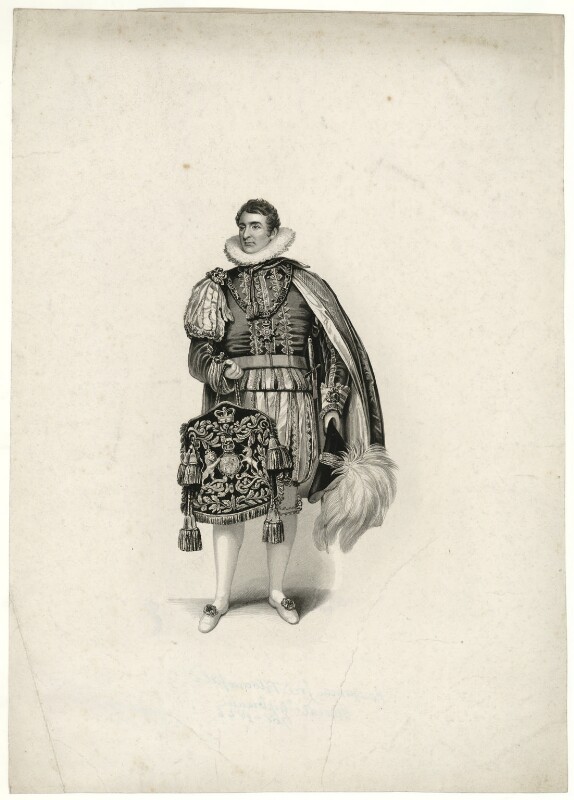

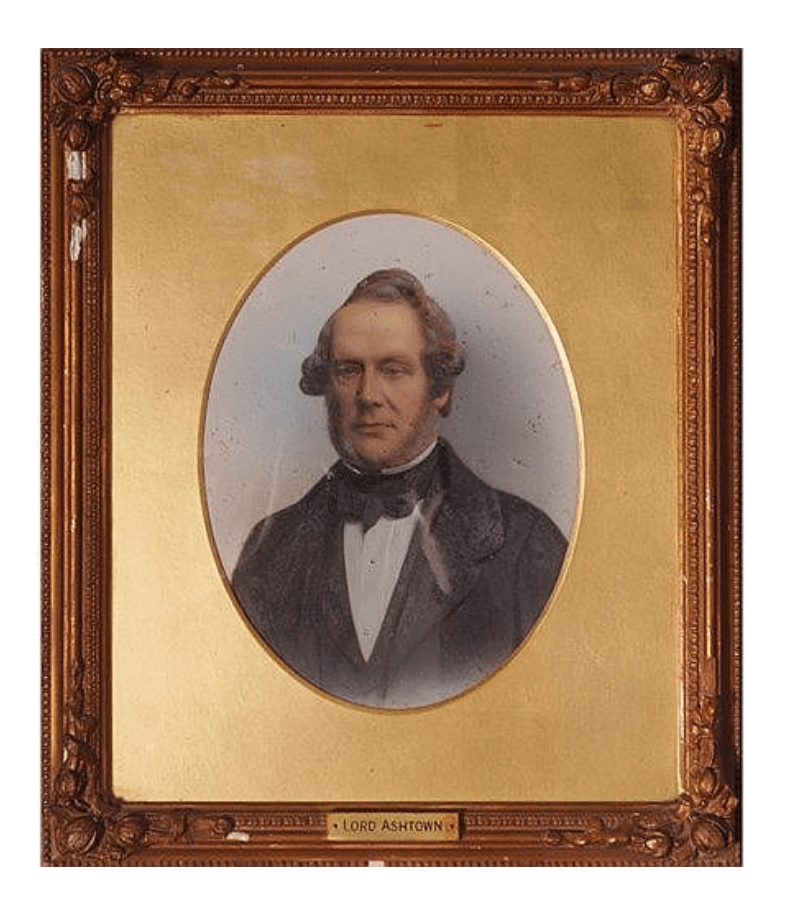

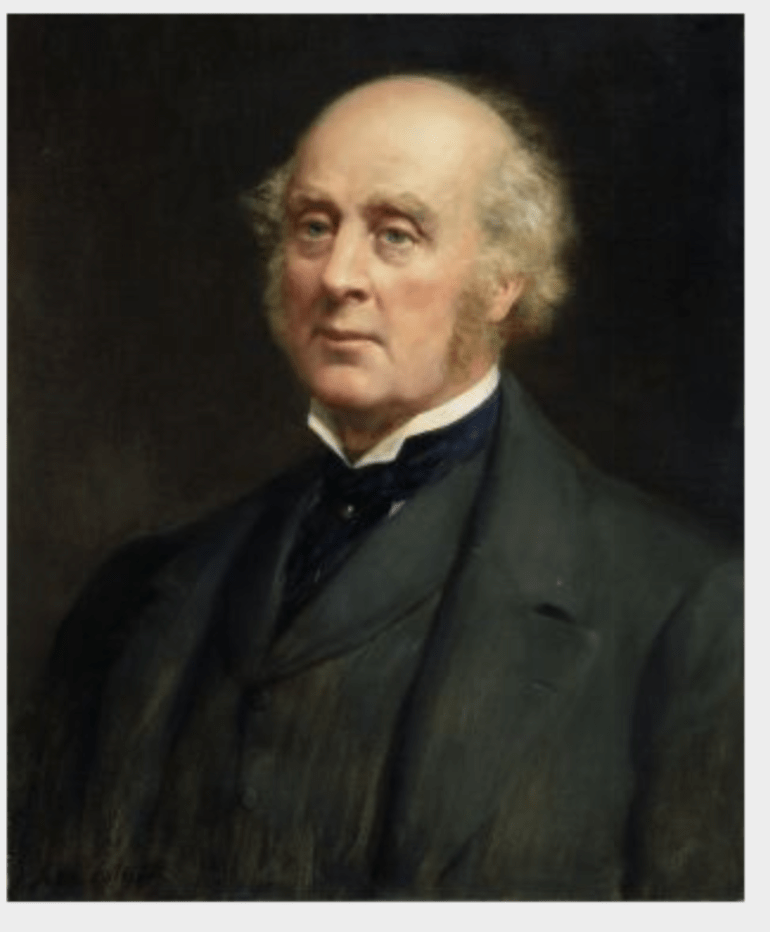

The Baronetcy then passed to his son James Talbot (1805-1883) 4th Baron of Malahide. He was an antiquarian and archaeologist.

The Malahide History Site describes the 4th Baron’s achievements:

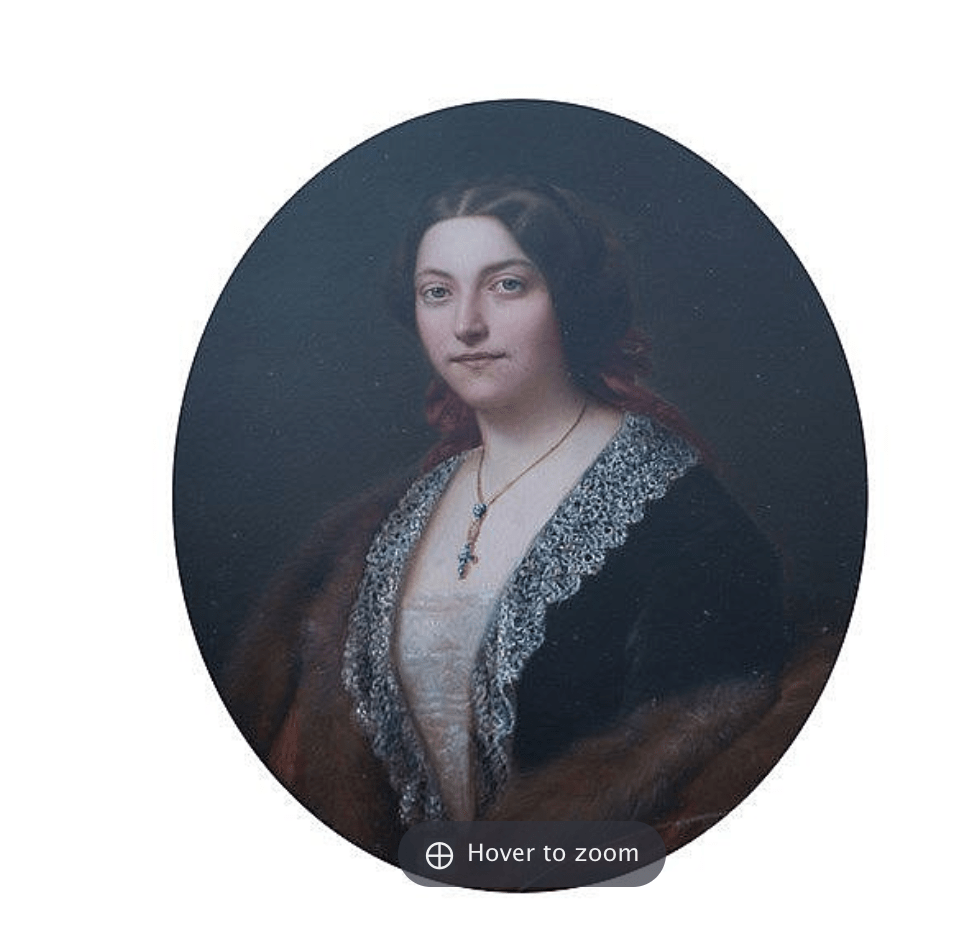

“In 1838 he set off with his aunt Eliza from Ballinclea House in Killiney on an extended tour of Europe and the near east. They spent over two years abroad during which he conducted much research while in Egypt and developed a keen interest in Roman antiquities. He succeeded his father as fourth Baron Talbot of Malahide in 1850 having already been in residence in Malahide and in 1856 he was created a peer of the United Kingdom as Baron Talbot de Malahide, in the County of Dublin. This gave him a seat in the House of Lords where he contributed regularly and from 1863 to 1866 he served as a Lord-in-Waiting (government whip) in the Liberal administrations of Lord Palmerston and Lord Russell. He was also a magistrate for Co. Dublin. James Talbot was also a noted amateur archaeologist and an active member of the Royal Archaeological Institute, serving as president for 30 years. Moreover, he was a Fellow of the Royal Society and of the Society of Antiquaries of London and served as president of the Royal Irish Academy. He was president also of the Geological and Zoological Societies of Ireland and vice-president of the Royal Dublin Society where he was a regular exhibitor of cattle at its shows. In that society’s autumn show he won a prize for seventeen varieties of farm produce from Lambay. He was instrumental in the revival of the Fingal Farming Society. Lord Talbot of Malahide married a well-to-do Scottish heiress, Maria Margaretta, daughter of Patrick Murray, of Simprim, Forfarshire, in 1842 but was left a widower in August, 1873. She was the last to be buried in the crypt in Malahide Abbey under the altar tomb associated with Maud Plunkett. He had a family of seven children. He died in Madeira in April 1883, aged 77, and was succeeded in his titles and estates by his eldest son.“

The Malahide History Site tells us that a gas-making plant was purchased from Messrs Edmundson of Capel Street in Dublin in 1856 and erected on The Green in the village. Apart from providing street lighting, the gas appears to have been piped to the castle thus making it one of the earlier houses to have gas lighting installed.

James’s son Richard Wogan Talbot (1846-1921) was next in line as 5th Baron. He also sounds like a fascinating character. He joined an exploration party making researches into the interior of Africa, and later published an account of his adventures. He found the estate in poor condition when he inherited, so he saved all that he could to put the castle and estate in order. [see 7]

Richard married Emily Harriette Boswell, and after his death their son James Boswell Talbot became the 6th Baron. Emily Harriette was the granddaughter of James Boswell the biographer of Samuel Johnson, author of the Dictionary of the English Language in 1775. When Emily died in 1898, Richard Talbot inherited the Boswell estate in Auchinleck, Scotland. This included an ebony cabinet full of the writer’s papers! In 1986 the remains of the buildings at Auchinleck were turned over to the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust by James Boswell, a descendant of the 18th-century Boswells. Now restored, Auchinleck House is used for holiday lets through the Landmark Trust, and is occasionally open to the public.

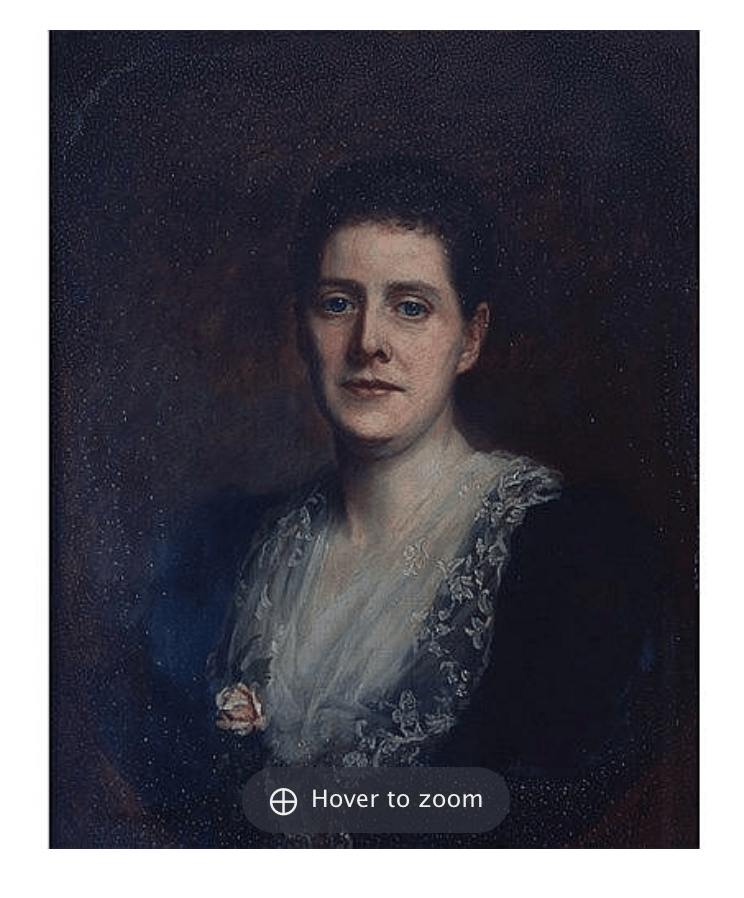

Richard the 5th Baron and his son spent much time travelling and the castle was left empty for long periods. He married for a second time in 1901 and he and his wife returned to live in Malahide. Several of his wife Isabelle’s paintings hang in the castle. She filled the house with children from her first marriage to John Gurney of Ham House and Sprowston Hall in England. She became head of the Dublin branch of the Red Cross during World War I and was awarded an O.B.E. in 1920.

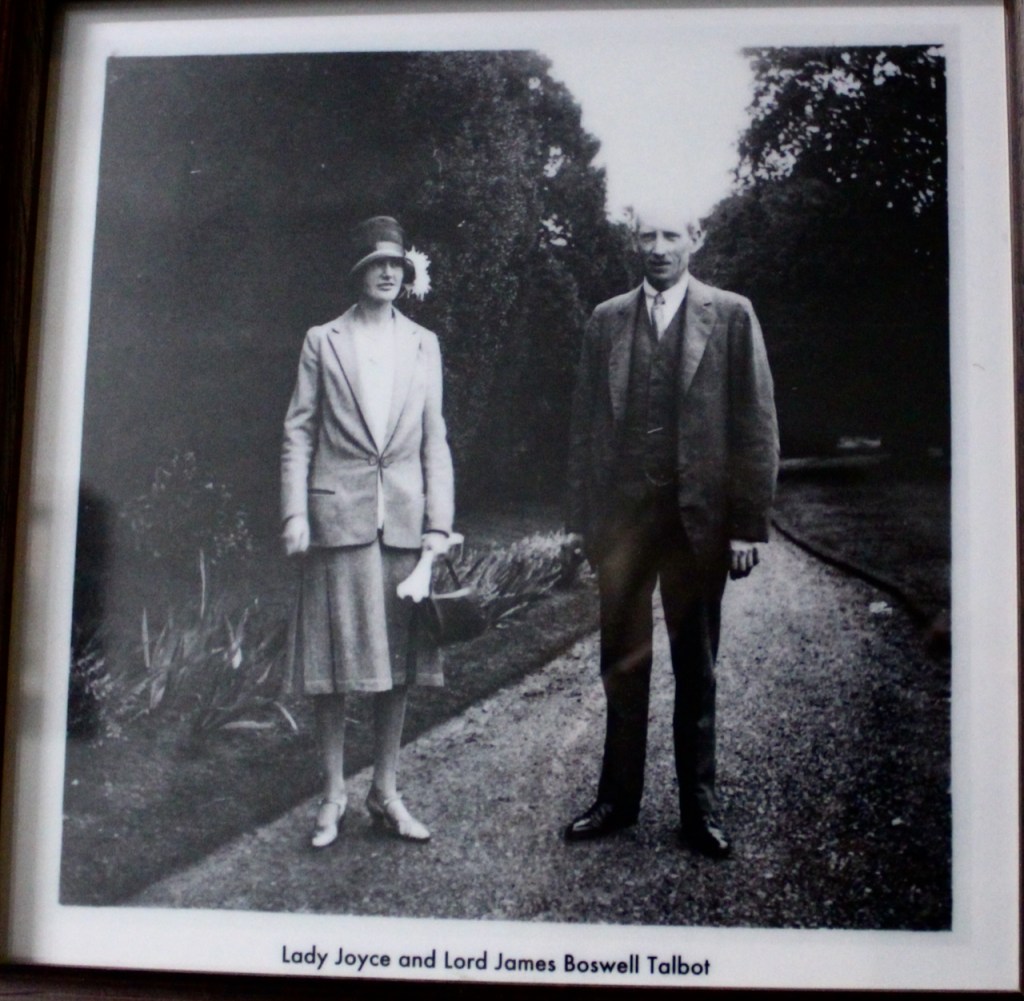

James Boswell Talbot the 6th Baron’s main interests were horse racing, Irish wolfhounds and fishing. He married at aged 50 Joyce Gunning Kerr, the eighteen year old daughter of an actor and London theatre manager. He fished at Mountshannon where he and his wife maintained a lodge and boat. Having inherited about 3,000 acres he had, by 1946, sold all but the 300 acres around the castle. He was of a retiring disposition but popular locally. His new wife assumed much of the day-to-day management of the castle. Lady Joyce took a keen interest in the Boswell Papers and was closely involved in their sale but not before she attempted to censor some of Boswell’s more explicit descriptions of his sexual encounters. They had no children so when he died in 1948 the title went to a grandson of the 4th Baron, Milo, who became 7th Baron, and who inherited Malahide Castle and estate.

Milo would not have grown up expecting the title, as his father had an elder brother who predeceased him by just one year, but this brother did not have children.

Milo the 7th Baron was a diplomat in Laos when he inherited Malahide Castle and was later Ambassador to Laos. He never married. He returned to live in the castle and died in 1973.

He is yet another fascinating character and is described on the Malahide Historical Society website:

“Much of Milo’s career during the 1940s and early 50s is shrouded in mystery and rumour. At Cambridge, Guy Burgess had been his history tutor and Anthony Blount had also tutored him. Kim Philby and Donald Maclean were also at Cambridge around this time. Milo is thought to have worked in the Secret Service for some years during World War II and to have encountered some of these men in the Foreign Office and in diplomatic postings abroad especially at Ankara in Turkey. In the course of Milo’s time at the Foreign Office during the Cold War Burgess and Maclean defected to the Russians after Philby alerted them to the fact that they were under suspicion. Milo retired in 1956 aged 45. Philby subsequently defected to be followed by Blount who was exposed as a double agent and who had been a regular guest of Milo at Malahide Castle. When Milo died suddenly in Greece when apparently in good health rumours and innuendos again circulated. No post mortem was carried out. Milo’s sister Rose burned his papers immediately on his death and many of the Foreign Office papers relating to him have disappeared.” [see 7]

When Milo the 7th Baron died the barony expired, and Malahide Castle and demesne was inherited by his sister Rose. Two years later, in 1975, she sold the castle to the Irish state, partly due to inheritance taxes. She moved to family property in Tasmania.

We saw two bedrooms after touring the formal rooms.

A flushing toilet was installed in 1870. Queen Victoria had a similar one, designed by Thomas Crapper.

The castle is surrounded by extensive lawns and woodland, and includes a butterfly house! There’s also a Victorian conservatory.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/media/100792

[2] https://www.archiseek.com/2011/1765-malahide-castle-co-dublin/

[3] https://www.malahidecastleandgardens.ie/castle/a-brief-history/

[4] Mark Bence-Jones A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[5] Dublin City Library and Archives. https://repository.dri.ie

[6] https://www.dib.ie/biography/browne-thomas-wogan-a1055 and Hugh A. Law “Sir Charles Wogan,”

The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Seventh Series, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Dec. 31, 1937), pp. 253-264 (12 pages), on JStor https://www.jstor.org/stable/25513883?read-now=1&seq=5#page_scan_tab_contents

[6] https://www.malahideheritage.ie/Other-Notable-Talbots.php