Carlow, Dublin, Kildare, Kilkenny, Laois, Longford, Louth, Meath, Offaly, Westmeath, Wexford and Wicklow are the counties that make up the Leinster region.

I have noticed that an inordinate amount of OPW sites are closed ever since Covid restrictions, if not even before that (as in Emo, which seems to be perpetually closed) [these sites are marked in orange here]. I must write to our Minister for Culture and Heritage to complain.

Laois:

1. Emo Court, County Laois – house closed at present

2. Heywood Gardens, County Laois

Longford:

3. Corlea Trackway Visitor Centre, County Longford

Louth:

4. Carlingford Castle, County Louth

5. Old Mellifont Abbey, County Louth – closed at present

Meath:

6. Battle of the Boyne site, Oldbridge House, County Meath

7. Hill of Tara, County Meath

8. Loughcrew Cairns, County Meath – guides on site from June 16th 2022

9. Newgrange, County Meath

10. Trim Castle, County Meath

Offaly:

11. Clonmacnoise, County Offaly

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Laois:

1. Emo Court, County Laois:

General enquiries: 057 862 6573, emocourt@opw.ie

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/10/22/emo-court-county-laois-office-of-public-works/

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/:

“Emo Court is a quintessential neo-classical mansion, set in the midst of the ancient Slieve Bloom Mountains. The famous architect James Gandon, fresh from his work on the Custom House and the Four Courts in Dublin, set to work on Emo Court in 1790. However, the building that stands now was not completed until some 70 years later [with work by Lewis Vulliamy, a fashionable London architect, who had worked on the Dorchester Hotel in London and Arthur & John Williamson, from Dublin, and later, William Caldbeck].

“The estate was home to the earls of Portarlington until the War of Independence forced them to abandon Ireland for good. The Jesuits moved in some years later [1920] and, as the Novitiate of the Irish Province, the mansion played host to some 500 of the order’s trainees.

“Major Cholmeley-Harrison took over Emo Court in the 1960s and fully restored it [to designs by Sir Albert Richardson]. He opened the beautiful gardens and parkland to the public before finally presenting the entire estate to the people of Ireland in 1994.

“You can now enjoy a tour of the house before relaxing in its charming tearoom. The gardens are a model of neo-classical landscape design, with formal lawns, a lake and woodland walks just waiting to be explored.” [2]

[1] p. 336. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[2] https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/

2. Heywood Gardens, Ballinakill, County Laois:

General enquiries: 086 810 7916, emocourt@opw.ie

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/05/02/heywood-gardens-ballinakill-county-laois-office-of-public-works/

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/heywood-gardens/:

“The entrancing eighteenth-century landscape at Heywood Gardens, near Ballinakill, County Laois, consists of gardens, lakes, woodland and some exciting architectural features. The park is set into a sweeping hillside. The vista to the south-east takes in seven counties.

“The architect Sir Edwin Lutyens designed the formal gardens [around 1906], which are the centrepiece of the property. It is likely that renowned designer Gertrude Jekyll landscaped them.

“The gardens are composed of elements linked by a terrace that originally ran along the front of the house. (Sadly, the house is no more.) One of the site’s most unusual features is a sunken garden containing an elongated pool, at whose centre stands a grand fountain.

“The Heywood experience starts beside the Gate Lodge. Information panels and signage will guide you around the magical Lutyens gardens and the surrounding romantic landscape.“

Longford:

3. Corlea Trackway Visitor Centre, Kenagh, County Longford:

General enquiries: 043 332 2386, corlea@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/corlea-trackway-visitor-centre/:

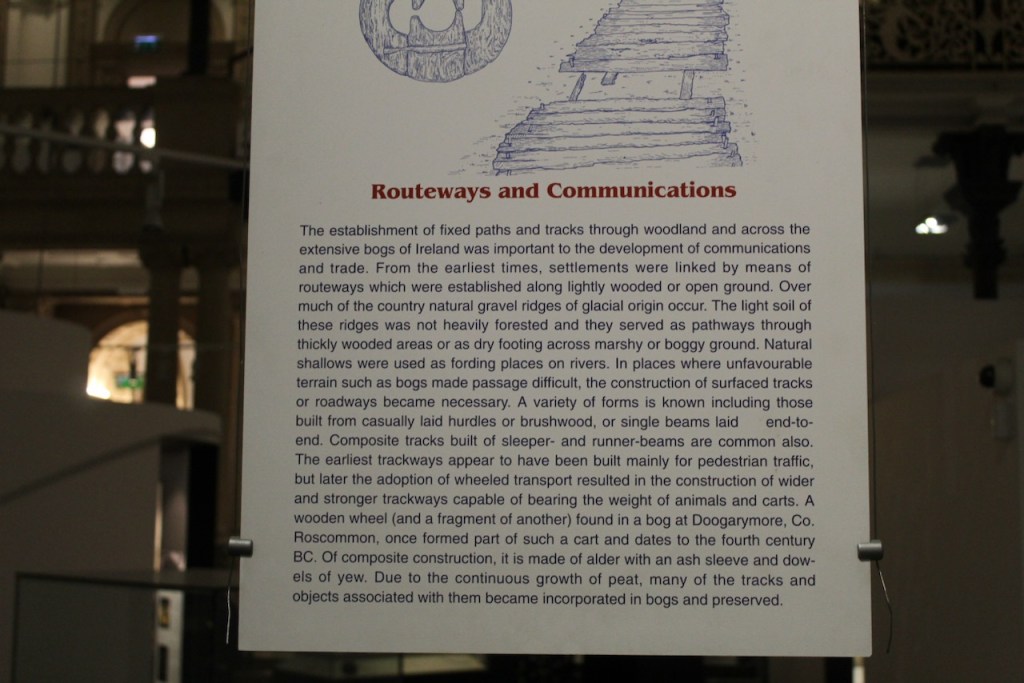

“Hidden away in the boglands of Longford, not far from Kenagh village, is an inspiring relic of prehistory: a togher – an Iron Age road – built in 148 BC. Known locally as the Danes’ Road, it is the largest of its kind to have been uncovered in Europe.

“Historians agree that it was part of a routeway of great importance. It may have been a section of a ceremonial highway connecting the Hill of Uisneach, the ritual centre of Ireland, and the royal site of Rathcroghan.

“The trackway was built from heavy planks of oak, which sank into the peat after a short time. This made it unusable, of course, but also ensured it remained perfectly preserved in the bog for the next two millennia.

“Inside the interpretive centre, an 18-metre stretch of the ancient wooden structure is on permanent display in a hall specially designed to preserve it. Don’t miss this amazing remnant of our ancient past.“

Louth:

4. Carlingford Castle, County Louth:

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/carlingford-castle/:

“Carlingford lies in the shade of Slieve Foye, a mountain that in legend takes its form from the body of the sleeping giant Finn MacCumhaill. The castle dominates the town and overlooks the lough harbour. It was a vital point of defence for the area for centuries.

“Carlingford Castle was built around 1190, most likely by the Norman baron Hugh de Lacy. By this time Hugh’s family had grown powerful enough to make King John of England uneasy. John forced them into rebellion and seized their property in 1210. He reputedly stayed in his new castle himself. It is still known as King John’s Castle.“

“The Jacobites fired on the castle in 1689; William of Orange is said to have accommodated his wounded soldiers there following the Battle of the Boyne.

“Carlingford Lough Heritage Trust provides excellent guided tours of this historic Castle from March to October.“

By 1778 the building was ruinous. The task of repair and preservation was begun by the Henry Paget the 1st Marquess of Anglesey in the later nineteenth century (he served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1848, and as Master General of the Ordinance), and has been continued by the OPW. [13]

5. Old Mellifont Abbey, Tullyallen, Drogheda, County Louth:

General enquiries: 041 982 6459, mellifontabbey@opw.ie. Mellifont means “fountain of honey.”

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/old-mellifont-abbey/:

“Mellifont Abbey was the first Cistercian monastery in Ireland. St Malachy of Armagh created it in 1142 with the help of a small number of monks sent by St Bernard from Clairvaux [and with the aid of Donough O’Carroll, King of Oriel – see 14]. The monks did not take well to Ireland and soon returned to France, but the abbey was completed anyway and duly consecrated with great pomp.

“It has several extraordinary architectural features, the foremost of which is the two-storey octagonal lavabo [the monk’s washroom].

“The monks at Mellifont hosted a critical synod in 1152. The abbey was central to the history of later centuries, too, even though it was in private hands by then. The Treaty of Mellifont, which ended the Nine Years War, was signed here in 1603, and William of Orange used the abbey as his headquarters during the momentous Battle of the Boyne.“

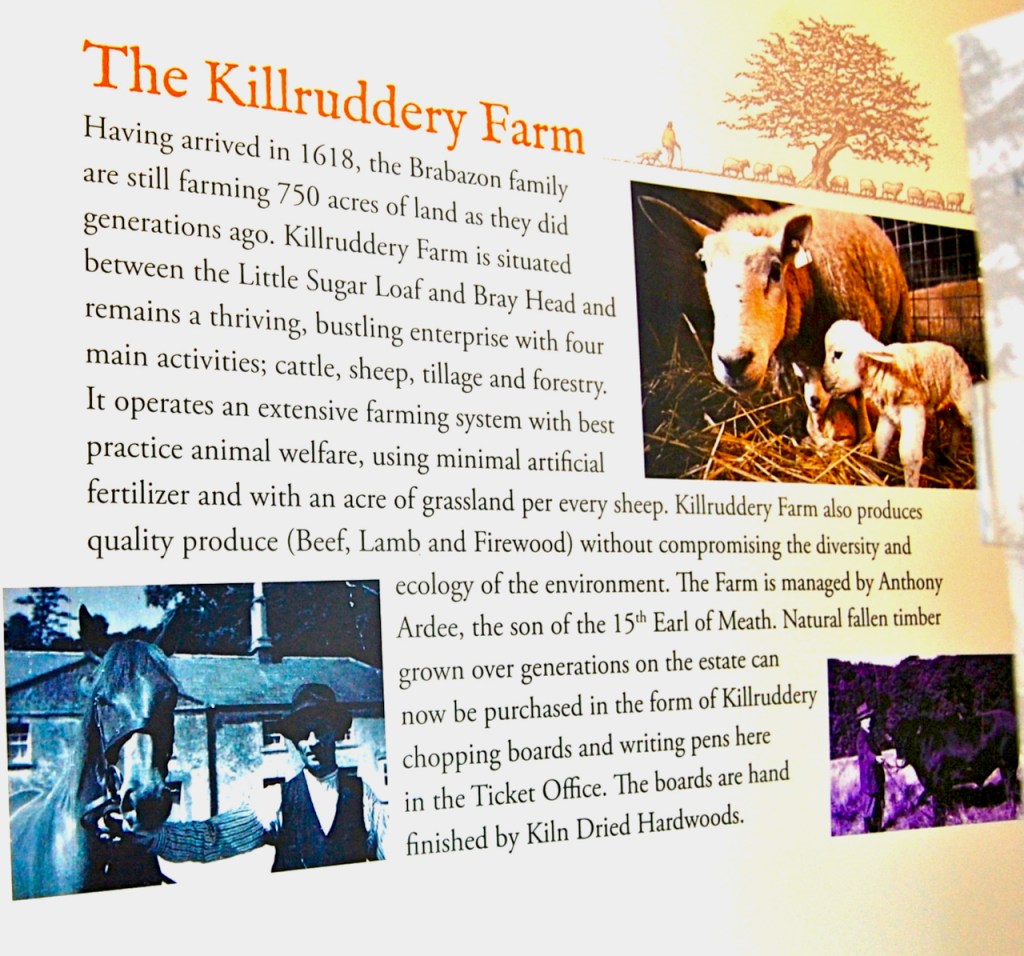

The ruins contain the medieval gatehouse, parish church, chapter house and lavabo. The octagonal lavabo was designed as a freestanding structure of two storeys, with an octagonal cistern to supply the water located at the upper level over the wash room. Wash basins were arranged around a central pier, now gone, which supported the weight of the water above. [14] The entire monastery was surrounded by a defensive wall. After the dissolution of the monasteries, Mellifont was acquired in 1540 by William Brabazon (died 1552), Vice Treasurer of Ireland, and passed later to Edward Moore (Brabazon’s wife Elizabeth Clifford remarried three times after Brabazon’s death, and one of her husbands was Edward Moore), who established a fortified house within the ruins around 1560. His descendents (Viscounts of Drogheda) lived there until 1727 (until the time of Edward Moore, 5th Earl of Drogheda), after which the house, like the abbey, fell into disrepair.

Garret Moore, 1st Viscount of Drogheda, hosted the negotiations which led to the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603.

Meath:

6. Battle of the Boyne site and visitor centre, Oldbridge House, County Meath.

General Enquiries: 041 980 9950, battleoftheboyne@opw.ie

The Battle of the Boyne museum is housed in Oldbridge Hall, which is built on the site where the Battle of the Boyne took place. See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/12/12/oldbridge-hall-county-meath-site-of-the-battle-of-the-boyne-visitor-centre/

7. Loughcrew Cairns, Corstown, Oldcastle, County Meath:

general enquiries: 087 052 4975, info@heritageireland.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/loughcrew-cairns/:

“The Loughcrew cairns, also known as the Hills of the Witch, are a group of Neolithic passage tombs near Oldcastle in County Meath. Spread over four undulating peaks, the tombs are of great antiquity, dating to 3000 BC.

“Cairn T is one of the largest tombs in the complex. Inside it lies a cruciform chamber, a corbelled roof and some of the most beautiful examples of Neolithic art in Ireland. The cairn is aligned to sunrise at the spring and autumn equinoxes and at these times people gather there to greet the first rays of the sun.“

8. Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre, Newgrange and Knowth, County Meath.

General Information: 041 988 0300, brunaboinne@opw.ie

From the website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/bru-na-boinne-visitor-centre-newgrange-and-knowth/:

“The World Heritage Site of Brú na Bóinne is Ireland’s richest archaeological landscape and is situated within a bend in the River Boyne. Brú na Bóinne is famous for the spectacular prehistoric passage tombs of Knowth, Newgrange and Dowth which were built circa 3200BC. These ceremonial structures are among the most important Neolithic sites in the world and contain the largest collection of megalithic art in Western Europe.“

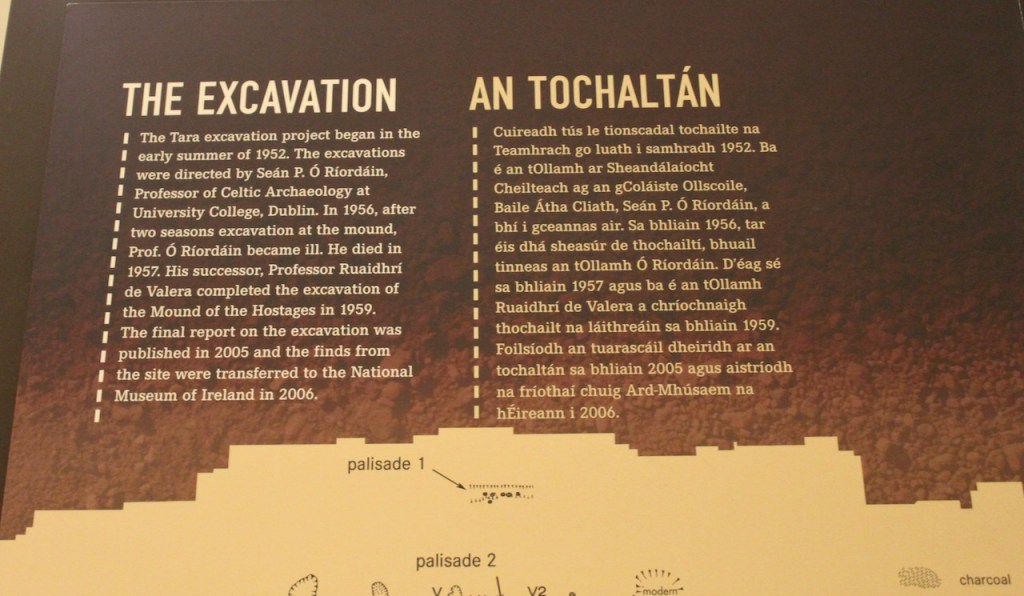

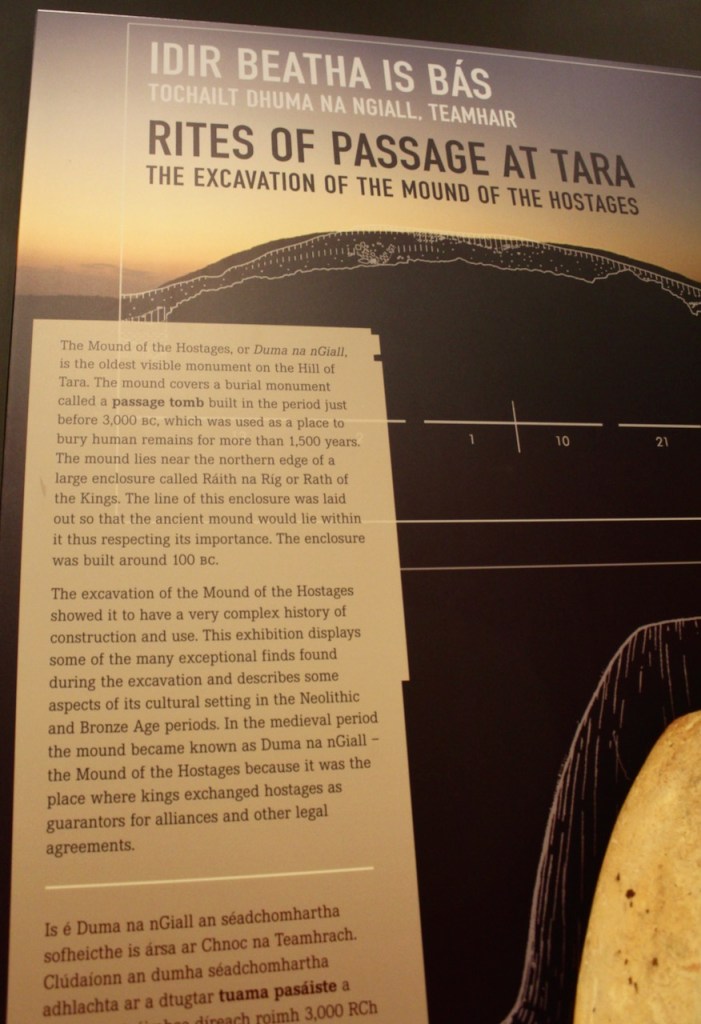

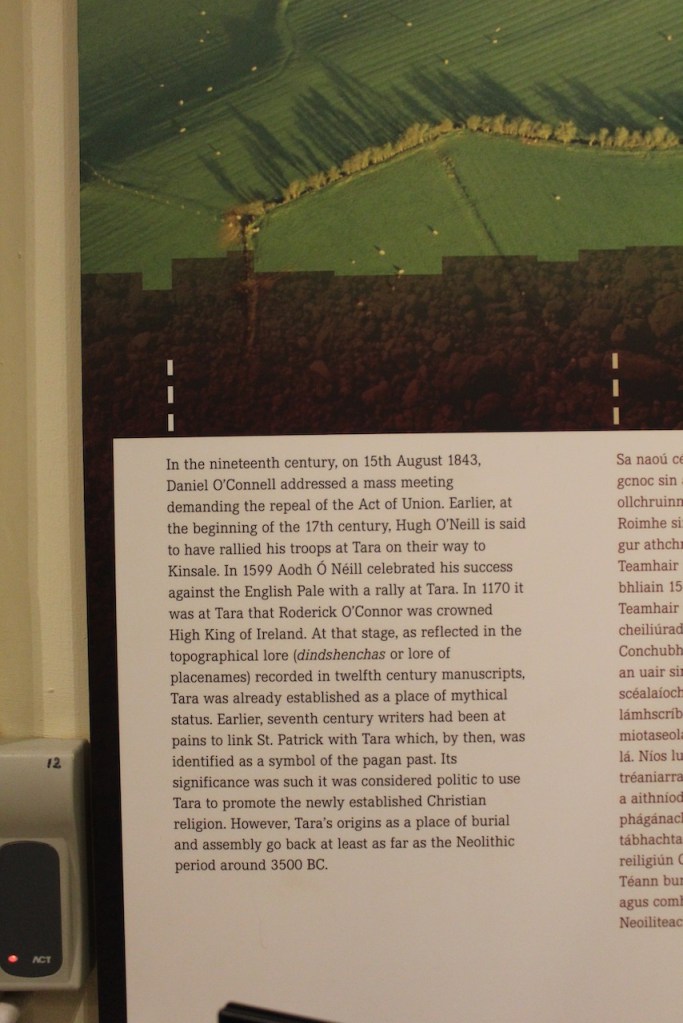

9. Hill of Tara, Navan, County Meath:

General information: 046 902 5903, hilloftara@opw.ie

From the OPW website:

“The Hill of Tara has been important since the late Stone Age, when a passage tomb was built there. However, the site became truly significant in the Iron Age (600 BC to 400 AD) and into the Early Christian Period when it rose to supreme prominence – as the seat of the high kings of Ireland. All old Irish roads lead to this critical site.

“St Patrick himself went there in the fifth century. As Christianity achieved dominance over the following centuries, Tara’s importance became symbolic. Its halls and palaces have now disappeared and only earthworks remain.

“There are still remarkable sights to be seen, however. Just one example is the Lia Fáil – the great coronation stone and one of the four legendary treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann – which stands proudly on the monument known as An Forradh.

“Guided tours of the site will help you understand the regal history of this exceptional place and imagine its former splendour.“

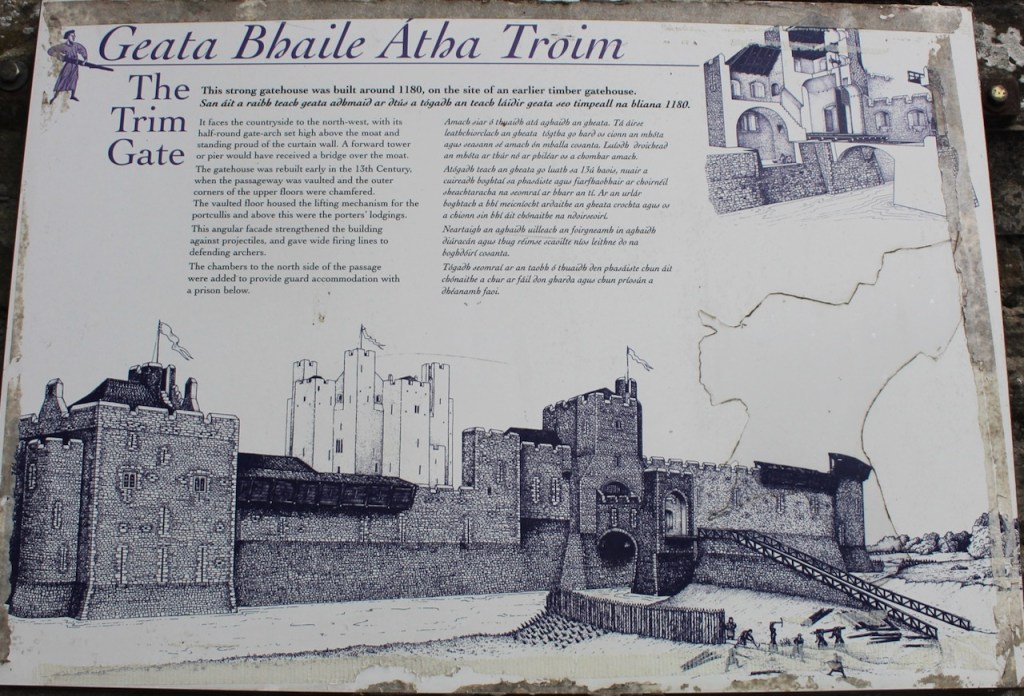

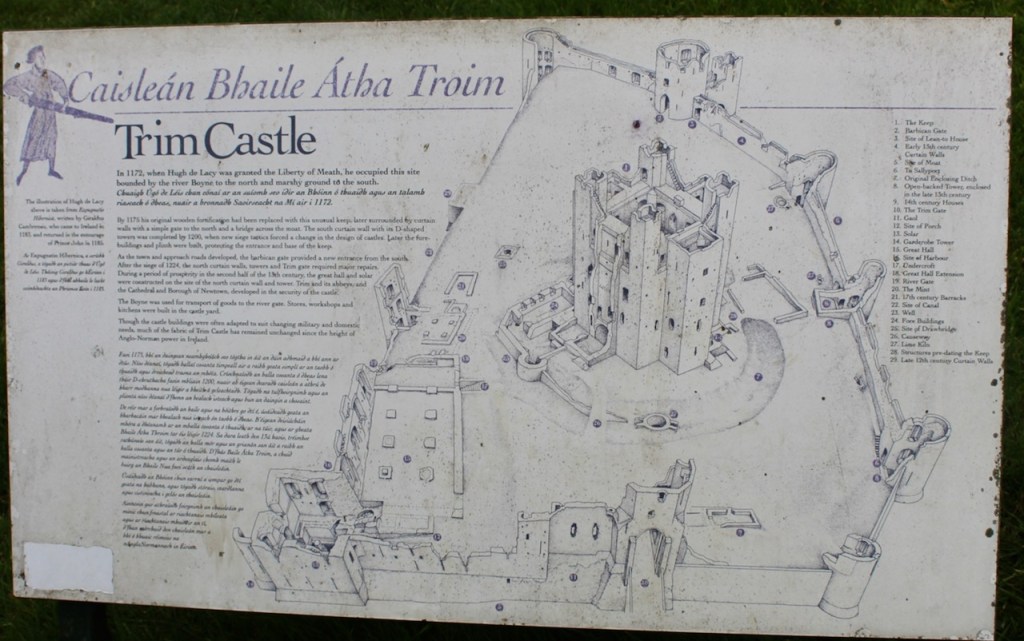

10. Trim Castle, County Meath:

General information: 046 943 8619, trimcastle@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/trim-castle/:

“Few places in Ireland contain more medieval buildings than the heritage town of Trim. Trim Castle is foremost among those buildings.

“In fact, the castle is the largest Anglo-Norman fortification in Ireland. Hugh de Lacy and his successors took 30 years to build it.

“The central fortification is a monumental three-storey keep. This massive 20-sided tower, which is cruciform in shape, was all but impregnable in its day. It was protected by a ditch, curtain wall and water-filled moat.

“Modern walkways now allow you to look down over the interior of the keep – a chance to appreciate the sheer size and thickness of the mighty castle walls.

“The castle is often called King John’s Castle although when he visited the town he preferred to stay in his tent on the other side of the river. Richard II visited Trim in 1399 and left Prince Hal later Henry V as a prisoner in the castle.” I never knew we had such a link to King Henry V and Shakespeare’s play, Henry IV!

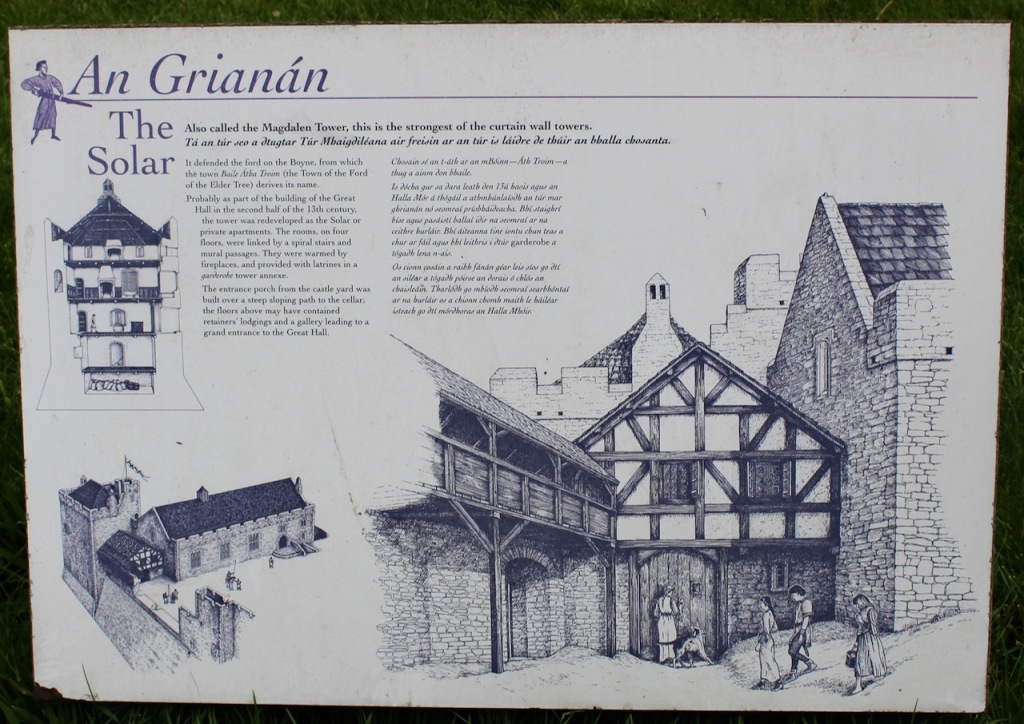

Patrick Comerford gives an excellent history of Trim Castle in his blog. [18] The castle stands within a three acre bailey, surrounded by a defensive perimeter wall. The curtain wall of the castle is fortified by a series of semicircular open-back towers. There were two entrances to Trim Castle, one, beside the car park, is flanked by a gatehouse, and the second is a barbican gate and tower. [19]

We visited in May 2022, after visiting St. Mary’s Abbey (also called Talbot’s Castle) – more on that soon. We were late entering so the entry to inside the castle was closed, unfortunately – we shall have to visit again!

The information board tells us that in 1182 when Hugh de Lacy was granted the Liberty of Meath, he occupied this site bounded by the River Boyne to the north and marshy ground to the south. By 1175 his original wooden fortification had been replaced by this unusual keep, later surrounded by curtain walls with a simple gate to the north and a bridge across the moat. The south curtain wall with its D shaped buildings was completed by 1200, when new siege tactics forced a change in the design of castles. Later, the forebuildings and plinth were built, protecting the entrance and base of the keep.

Sometime before 1180, Hugh de Lacy replaced the timber palisade fence enclosing the keep with a stone enclosure. The fore-court enclosed stables and stores and protected the stairway and door to the keep. The new entrance was on the north side of the enclosure and had a drawbridge over the deepened ditch.

With the development of the curtain walls, the inner enclosure became obsolete.

The ditch was filled and three defensive towers – two survive – were built on its site. The drawbridge was replaced by a stone causeway leading to an arched gate and entrance stairway. A reception hall was built to accommodate visitors before they entered the Keep.

As the town and approach roads developed, the barbican gate provided a new entrance from the south. After the siege of 1224, the north curtain walls, towers and Trim gate required major repairs. During a period of prosperity in the second half of the 13th century, the great hall and solar were constructed on the site of the north curtain wall and tower. Trim and its abbeys and the Cathedral and borough of Newtown developed in the security of the castle.

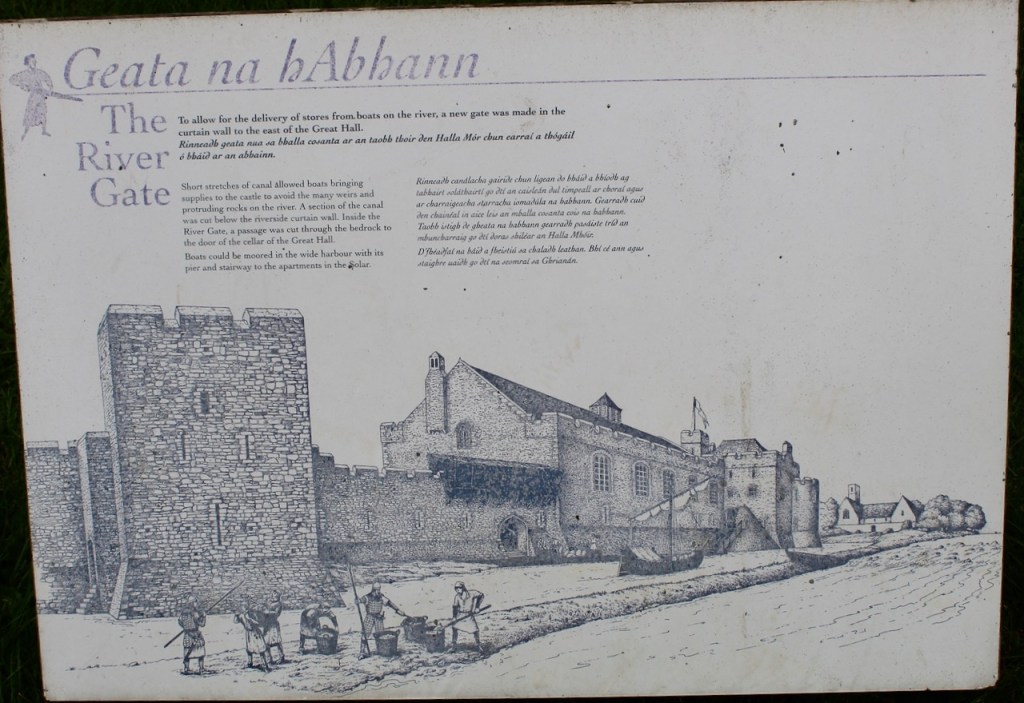

The Boyne was used for transport of goods to the river gate. Stores, workshops and kitchens were built in the castle yard.

Though the castle buildings were often adapted to suit changing military and domestic needs, much of the fabric of Trim Castle has remained unchanged since the height of Anglo-Norman power in Ireland.

The information board tells us that courts, parliaments, feasts and all issues relating to the management of the Lordship were discussed at meetings in the Great Hall. After 1250, the great public rooms in the Keep were considered unsuitable for such gatherings, so this hall was built, lit by large windows with a view of the harbour and the Abbey of St. Mary’s across the river. The hall had a high seat at the west end, with kitchens and undercroft cellars to the east. Ornate oak columns rising from stone bases supported the great span of the roof.

The hall was heated from a central hearth and vented by a lantern-like louvre in the roof.

Early in the 13th century the weirs were completed on the Boyne, allowing the moat to be flooded, and the Leper River was channelled along the south curtain wall. A new gate was constructed guarding the southern approaches to the castle. This gatehouse, of a rare design, was built as a single cylindrical tower with a “barbican,” defences of a forward tower adn bridge. An elaborate system of lifting bridges, gates and overhead traps gave the garrison great control over those entering the castle. The arrangement of plunging loops demonstrates the builders’ knowledge of the military requirements of defending archers.

By the middle of the 13th century, the design of castle gates was further developed and a twin tower gatehouse with a passage between the two towers became standard.

Offaly:

11. Clonmacnoise, County Offaly:

General information: 090 9674195, clonmacnoise@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/clonmacnoise/:

“St Ciarán founded his monastery on the banks of the River Shannon in the 6th Century. The monastery flourished and became a great seat of learning, a University of its time with students from all over Europe.

“The ruins include a Cathedral, two round Towers, three high crosses, nine Churches and over 700 Early Christian graveslabs.

“The original high crosses, including the magnificent 10th century Cross of the Scriptures area on display in a purpose built visitor centre adjacent the monastic enclosure.

“An audiovisual presentation will give you an insight into the history of this hallowed space.“

[1] p. 336. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[2] https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/

[3] p. 119. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://emocourt.ie/history/

For information on Gandon’s house in Lucan, see https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/11201034/canonbrook-house-lucan-newlands-road-lucan-and-pettycanon-lucan-dublin

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2019/02/27/emo-court/

[6] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/media/81101

[7] http://www.fatherbrowne.com

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/14/of-changes-in-taste/

and https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/02/01/seen-in-the-round/

For photographs of the stuccowork, see https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/21/forgotten-virtuosi/

[9] p. 96. Sadleir, Thomas U. and Page L. Dickinson. Georgian Mansions in Ireland with some account of the evolution af Georgian Architecture and Decoration. Dublin University Press, 1915.

[10] p. 356. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[11] p. 61. O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

[12] https://theirishaesthete.com/2018/08/27/heywood/

and https://theirishaesthete.com/2014/05/12/to-smooth-the-lawn-to-decorate-the-dale/

[13] p. 175, Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster: the counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

[14] p. 387, Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster: the counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

and see also my entry on Killineer, County Louth.

[18] http://www.patrickcomerford.com/2016/10/trim-castle-is-strong-symbol-in-stone.html

[19] p. 511, Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan. The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster: the counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, London, 1993.