General Enquiries: 01 645 8813, dublincastle@opw.ie

From the website:

“Just a short walk from Trinity College, on the way to Christchurch, Dublin Castle is well situated for visiting on foot. The history of this city-centre site stretches back to the Viking Age and the castle itself was built in the thirteenth century.

“The building served as a military fortress, a prison, a treasury and courts of law. For 700 years, from 1204 until independence, it was the seat of English (and then British) rule in Ireland.

“Rebuilt as the castle we now know in the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Dublin Castle is now a government complex and an arena of state ceremony.

“The state apartments, undercroft, chapel royal, heritage centre and restaurant are now open to visitors.“

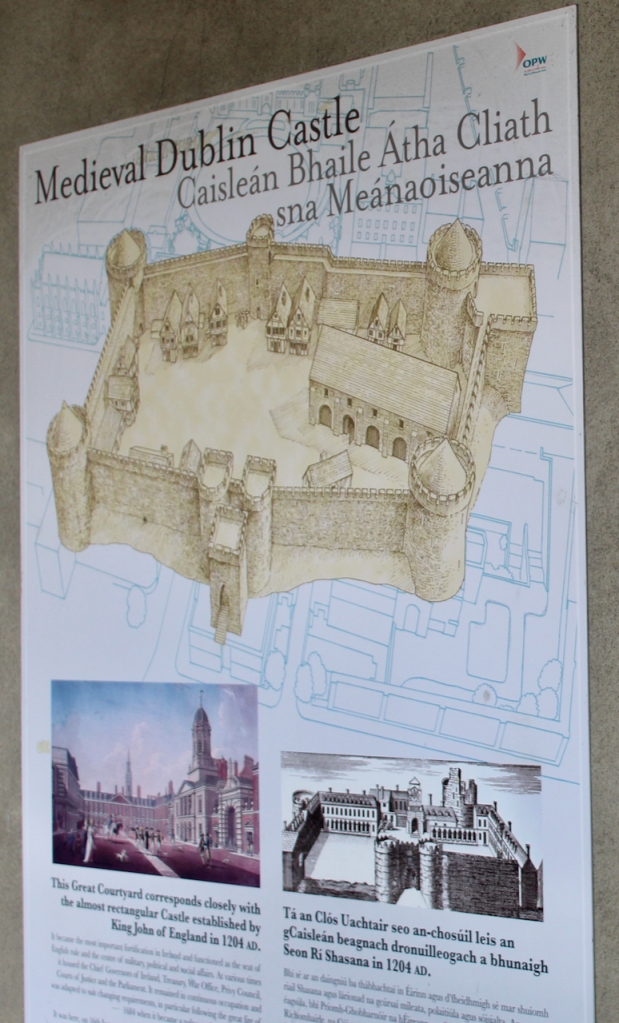

What is called “Dublin Castle” is a jumble of buildings from different periods and of different styles. The castle was founded in 1204 by order of King John who wanted a fortress constructed for the administration of the city. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the castle contained law courts, meeting of Parliament, the residence of the Viceroy and a council chamber, as well as a chapel.

The oldest parts remaining are the medieval Record Tower from the thirteenth century and the tenth century stone bank visible in the Castle’s underground excavation.

The first Lord Deputy (also called Lord Lieutenant or Viceroy) to make his residence here was Sir Henry Sidney (1529-1586) in 1565. He was brought up at the Royal Court as a companion to Prince Edward, afterwards King Edward VI. He served under both Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth I. He spent much of his time in Ireland expanding English administration over Ireland, which had reduced before his time to the Pale and a few outlying areas.

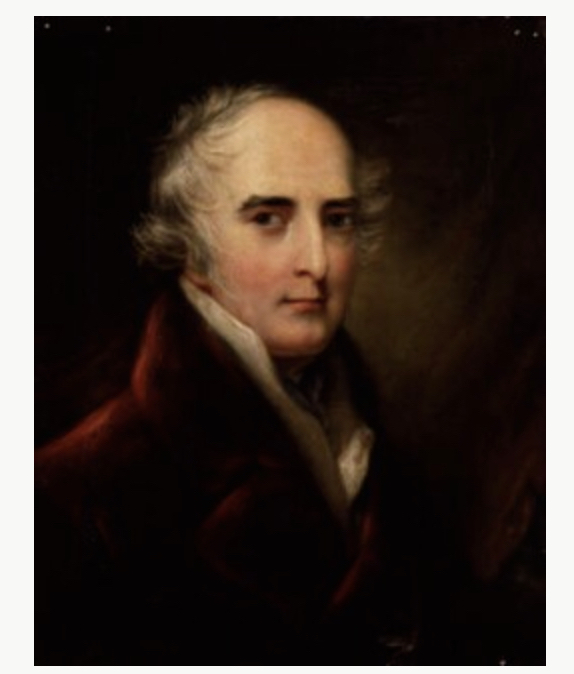

In 1684 a fire in the Viceregal quarters destroyed part of the building. The Viceroy at the time would have been James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond. He moved temporarily to the new building of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. New designs by the Surveyor General Sir William Robinson were constructed by October 1688, who also designed the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. He designed the State Apartments, originally to be living accommodation for the Lord Lieutenant (later known as the Viceroy), the representative for the British monarch in Ireland. [3] Balls and other events were held for fashionable society in the Castle. The State Apartments are now used for State occasions such as the Inauguration of the President. The Castle was formally handed over to General Michael Collins on 16th January 1922, and the Centenary of this event was commemorated in January 2022.

The State Apartments consist of a series of ornate decorated rooms, stretching along the first floor of the southern range of the upper yard.

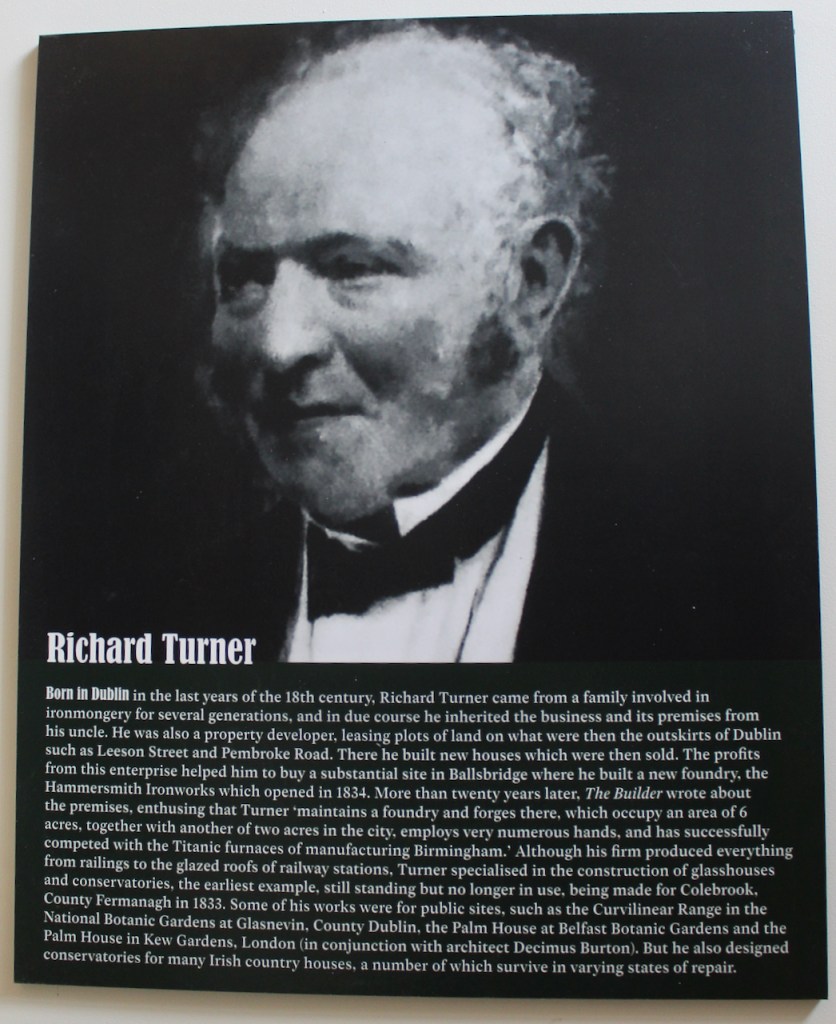

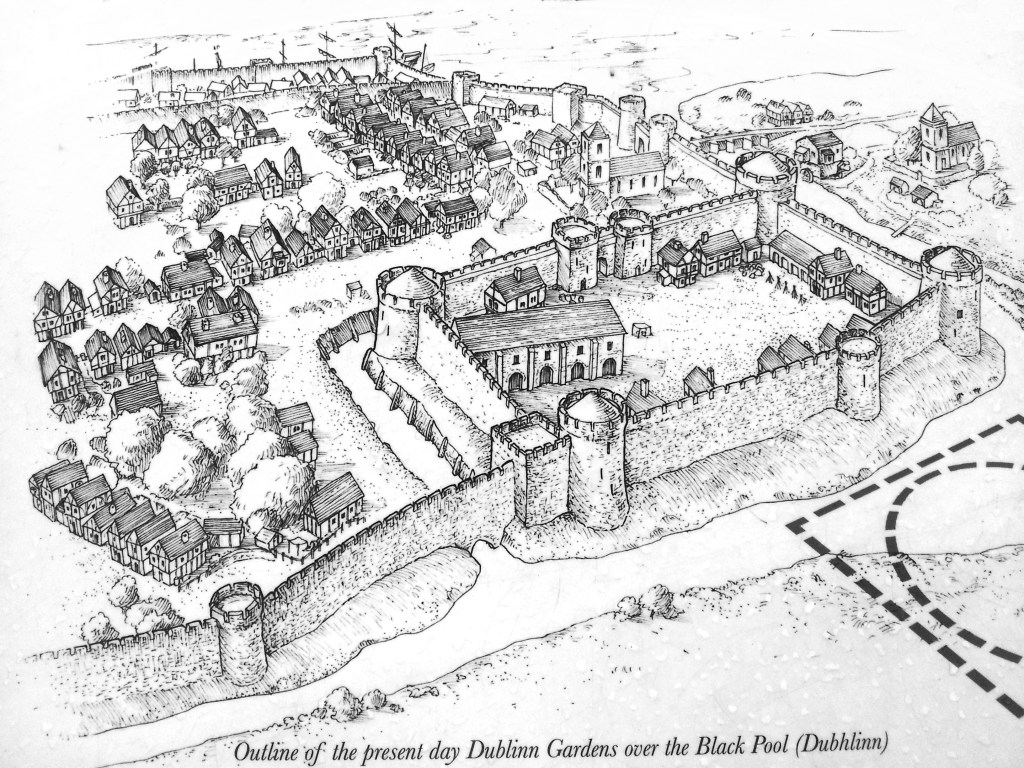

Located around the castle within the castle grounds are the Coach House Gallery, Garda Museum, the Revenue Museum, the Hibernia Conference Centre and the Chester Beatty Museum and Dubh Linn Gardens, which are located on the original “dubh linn” or black pool of Dublin.

The Bedford Tower was constructed around 1750 along with its flanking gateways to the city. The clock tower is named after the 4th Duke of Bedford John Russell who was Lord Lieutenant at the time.

The Chapel Royal, renamed the Church of the Most Holy Trinity in 1943, was designed by Francis Johnston in 1807. It is built on the site of an earlier church which was built around 1700. The exterior is decorated with over 100 carved stone heads by Edward Smyth, who did the river heads on Dublin’s Custom House, and by his son John. They are carved in Tullamore limestone, and represent a variety of kings, queens, archbishops and ‘grotesques’. A carving of Queen Elizabeth I is on the north façade and Saint Peter and Jonathan Swift above the main entrance. The interior of the chapel has plasterwork by George Stapleton and wood carving by Richard Stewart. What looks like carved stone is actually limestone ashlar facing on a structure of timber, covered in painted plaster. Plasterwork fan vaulting, inspired by Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster Abbey, is by George Stapleton (1777-1841) while a host of modelled plasterwork heads are by the Smyths, likely the work of John (the younger) after the death of his father in 1812. [9] The Arms of all the Viceroys from 1172-1922 are on display.

Returning to the State Apartments in the Upper Courtyard, The State Corridor on the first floor of the State Apartments is by Edward Lovett Pearce in 1758.

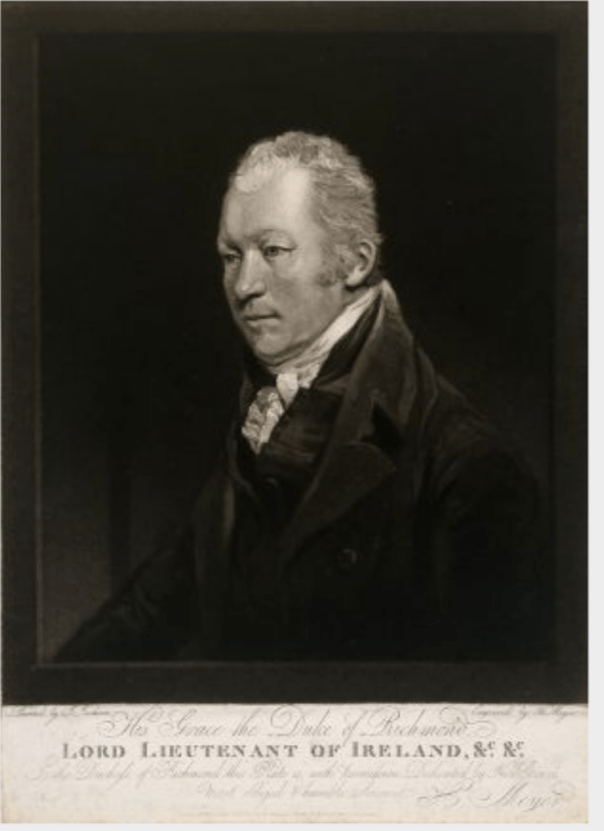

The Viceroy at the time of Francis Johnston’s work on the chapel would have been Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond.

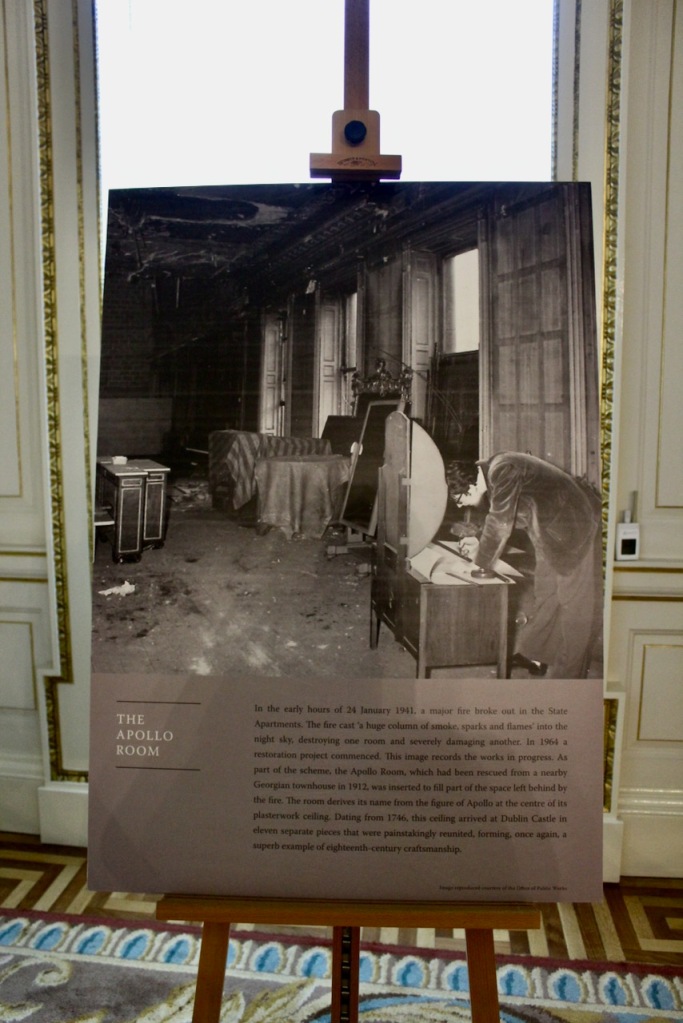

The Drawing room was largely destroyed in a fire in 1941, and was reconstructed in 1968 in 18th century style. It is heavily mirrored with five large Waterford crystal chandeliers.

The Throne Room, originally known as Battleaxe Hall, has a throne created for the visit of King George IV in 1821. The walls are decorated with roundels painted by Gaetano Gandolfi, depicting Jupiter, Juno, Mars and Venus. The Throne Room was created by George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham, the viceroy of the day.

Next to the Throne Room is the Portrait Gallery, where formal banquets took place at the time of the Viceroys.

There are many other important rooms, including the Wedgwood Room, an oval room decorated in Wedgwood Blue with details in white, which was used as a Billiards Room in the 19th century. It dates from 1777.

Beyond the Wedgwood Room is the Gothic Room, and then St. Patrick’s Hall. It has two galleries, one at each end, initially intended as one for musicians and one for spectators. There are hanging banners of the arms of the members of the Order of St Patrick, the Irish version of the Knight of the Garter: they first met here in 1783. The room is in a gold and white colour scheme with Corinthian columns. The painted ceiling, commissioned and paid for by the viceroy George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham in 1788, is by Vincenzo Valdre (c. 1742-1814), an Italian who was brought to Ireland by his patron the Marquess of Buckingham. In the central panel, George III is between Hibernia and Brittania, with Liberty and Justice. Other panels depict St. Patrick, and Henry II receiving the surrender of Irish chieftains.

The hall was built originally as a ballroom in the 1740s but was damaged by an explosion in 1764, remodelled in 1769, and redecorated in the 1780s in honour of the Order of St Patrick.

The following is a list of the Lord Lieutenants of Ireland (courtesy of wikipedia):

Under the House of Anjou

- Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath: 1172–73

- William FitzAldelm: 1173

- Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (Strongbow): 1173–1176

- William FitzAldelm: 1176–1177

- Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath: 1177–1181

- John fitz Richard, Baron of Halton, Constable of Chester and Richard Peche, Bishop of Lichfield, jointly: 1181

- Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath and Hubert Walter, Bishop of Salisbury, jointly: (1181–1184)

- Philip de Worcester: 1184–1185

- John de Courcy: 1185–1192

- William le Petit & Walter de Lacy: 1192–1194

- Walter de Lacy & John de Courcy: 1194–1195

- Hamo de Valognes: 1195–1198

- Meiler Fitzhenry: 1198–1208

- John de Gray, Bishop of Norwich: 1208–1213

- William le Petit 1211: (during John’s absence)

- Henry de Loundres, Archbishop of Dublin: 1213–1215

- Geoffrey de Marisco: 1215–1221

Under the House of Plantagenet

- Henry de Loundres, Archbishop of Dublin: 1221–1224

- William Marshal: 1224–1226

- Geoffrey de Marisco: 1226–1228

- Richard Mor de Burgh: 1228–1232

- Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent 1232 (held the office formally, but never came to Ireland)[3]

- Maurice FitzGerald, 2nd Lord of Offaly: 1232–1245

- Sir John Fitz Geoffrey: 1246–1256

- Sir Richard de la Rochelle 1256

- Alan de la Zouche: 1256–1258

- Stephen Longespée: 1258–1260

- William Dean: 1260–1261

- Sir Richard de la Rochelle: 1261–1266

- David de Barry 1266–1268

- Robert d’Ufford 1268–1270

- James de Audley: 1270–1272

- Maurice Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald: 1272–1273

- Geoffrey de Geneville: 1273–1276

- Sir Robert D’Ufford: 1276–1281

- Stephen de Fulbourn, Archbishop of Tuam: 1281–1288

- John de Sandford, Archbishop of Dublin: 1288–1290

- Sir Guillaume de Vesci: 1290–1294

- Sir Walter de la Haye: 1294

- William fitz Roger, prior of Kilmainham 1294

- Guillaume D’Ardingselles: 1294–1295

- Thomas Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald: 1295

- Sir John Wogan: 1295–1308

- Edmund Butler 1304–1305 (while Wogan was in Scotland)

- Piers Gaveston: 1308–1309

- Sir John Wogan: 1309–1312

- Edmund Butler, Earl of Carrick: 1312–1314

- Theobald de Verdun, 2nd Baron Verdun: 1314–1315

- Edmund Butler, Earl of Carrick: 1315–1318

- Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March: 1317–1318

- William FitzJohn, Archbishop of Cashel: 1318

- Alexander de Bicknor, Archbishop of Dublin: 1318–19

- Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March 1319–1320

- Thomas FitzGerald, 2nd Earl of Kildare: 1320–1321

- Sir Ralph de Gorges: 1321 (appointment ineffective)

- John de Bermingham, 1st Earl of Louth: 1321–1324

- John D’Arcy: 1324–1327

- Thomas FitzGerald, 2nd Earl of Kildare: 1327–1328

- Roger Utlagh: 1328–1329

- John D’Arcy: 1329–1331

- William Donn de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster: 1331–1331

- Anthony de Lucy: 1331–1332

- John D’Arcy: 1332–1338 (Lords Deputy: Sir Thomas de Burgh: 1333–1337 and Sir John Charlton: 1337–1338)

- Thomas Charleton, Bishop of Hereford: 1338–1340

- Roger Utlagh: 1340

- Sir John d’Arcy: 1340–1344 (Lord Deputy: Sir John Morice (or Moriz))

- Sir Raoul d’Ufford: 1344–1346 (died in office in April 1346)

- Roger Darcy 1346

- Sir John Moriz, or Morice: 1346–1346

- Sir Walter de Bermingham: 1346–1347

- John L’Archers, Prior of Kilmainham: 1347–1348

- Sir Walter de Bermingham: 1348–1349

- John, Lord Carew: 1349

- Sir Thomas de Rokeby: 1349–1355

- Maurice FitzGerald, 4th Earl of Kildare: 1355–1355

- Maurice FitzGerald, 1st Earl of Desmond: 1355–1356

- Maurice FitzGerald, 4th Earl of Kildare: 1356

- Sir Thomas de Rokeby: 1356–1357

- John de Boulton: 1357

- Maurice FitzGerald, 4th Earl of Kildare: 1357

- Almaric de St. Amaud, Lord Gormanston: 1357–1359

- James Butler, 2nd Earl of Ormond: 1359–1360

- Maurice FitzGerald, 4th Earl of Kildare: 1361

- Lionel of Antwerp, 5th Earl of Ulster (later Duke of Clarence): 1361–1364

- James Butler, 2nd Earl of Ormond: 1364–1365

- Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence: 1365–1366

- Thomas de la Dale: 1366–1367

- Gerald FitzGerald, 3rd Earl of Desmond: 1367–1369, a.k.a. Gearóid Iarla

- Sir William de Windsor: 1369–1376

- James Butler, 2nd Earl of Ormond: 1376–1378

- Alexander de Balscot and John de Bromwich: 1378–1380

- Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March: 1380–1381

- Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March: 1382 (first term, aged 11, Lord Deputy: Sir Thomas Mortimer)

- Sir Philip Courtenay: 1385–1386

- Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland: 1386

- Alexander de Balscot, Bishop of Meath: 1387–1389

- Sir John Stanley, K.G., King of Mann: 1389–1391 (first term)

- James Butler, 3rd Earl of Ormond: 1391

- Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester: 1392–1395

- Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March: 1395–1398 (second term)

- Thomas Holland, Duke of Surrey: 1399

Under the Houses of York and Lancaster

- Sir John Stanley: 1399–1402 (second term)

- Thomas of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Clarence: 1402–1405 (aged 13)

- James Butler, 3rd Earl of Ormond: 1405

- Gerald FitzGerald, 5th Earl of Kildare: 1405–1408

- Thomas of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Clarence: 1408–1413

- Sir John Stanley: 1413–1414 (third term)

- Thomas Cranley, Archbishop of Dublin: 1414

- John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury: 1414–1421 (first term)

- James Butler, 4th Earl of Ormond: 1419–1421 (first term)

- Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March: 1423–1425

- John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury: 1425 (second term)

- James Butler, 4th Earl of Ormond: 1425–1427

- Sir John Grey: 1427–1428

- John Sutton, later 1st Lord Dudley: 1428–1429

- Sir Thomas le Strange: 1429–1431

- Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley: 1431–1436

- Lionel de Welles, 6th Baron Welles: 1438–1446

- John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury: 1446 (third term)

- Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York: 1447–1460 (Lord Deputy: Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Kildare)

- George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence: 1462–1478 (Lords Deputy: Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Desmond/Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Kildare)

- John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk: 1478

- Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York: 1478–1483 (aged 5. Lord Deputy:Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare)

- Edward of Middleham: 1483–1484 (aged 11. Lord Deputy:Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare)

- John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln: 1484–1485

Under the House of Tudor

- Jasper Tudor, 1st Duke of Bedford| 1485–1494 (Lord Deputy:Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare)

- Henry, Duke of York: 1494–?1519 (Aged 4. Lords Deputy: Sir Edward Poynings/Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare/Gerald FitzGerald, 9th Earl of Kildare)

- Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk: 1519–1523 (Lord Deputy:Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey)

Lords Deputy

Under the House of Tudor

- The Earl of Ossory: 1523–1524

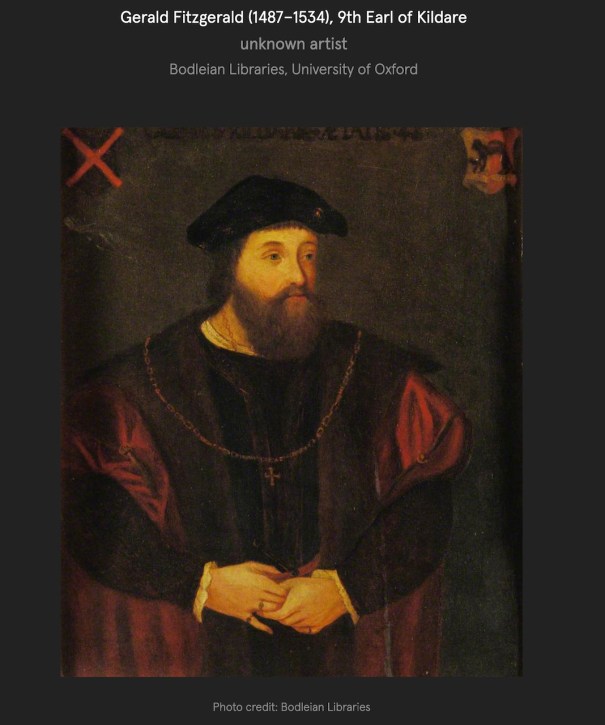

- Gerald FitzGerald, 9th Earl of Kildare: 1524–1529

- The Duke of Richmond and Somerset: 22 June 1529 (aged 10)

- Sir William Skeffington: 1529–1532

- Gerald FitzGerald, 9th Earl of Kildare: 1532–1534

- Sir William Skeffington: 30 July 1534

- Leonard Grey, 1st Viscount Grane: 23 February 1536 – 1540 (executed, 1540)

- Lords Justices: 1 April 1540

- Sir Anthony St Leger: 7 July 1540 (first term)

- Sir Edward Bellingham: 22 April 1548

- Lords Justices: 27 December 1549

- Sir Anthony St Leger: 4 August 1550 (second term)

- Sir James Croft: 29 April 1551

- Lords Justices: 6 December 1552

- Sir Anthony St Leger: 1 September 1553 – 1556 (third term)

- Viscount FitzWalter: 27 April 1556

- Lords Justices: 12 December 1558

- The Earl of Sussex (Lord Deputy): 3 July 1559

- The Earl of Sussex (Lord Lieutenant): 6 May 1560

- Sir Henry Sidney: 13 October 1565

- Lord Justice: 1 April 1571

- Sir William FitzWilliam: 11 December 1571

- Sir Henry Sidney: 5 August 1575

- Lord Justice: 27 April 1578

- The Lord Grey de Wilton: 15 July 1580

- Lords Justices: 14 July 1582

- Sir John Perrot: 7 January 1584

- Sir William FitzWilliam: 17 February 1588

- Sir William Russell: 16 May 1594

- The Lord Burgh: 5 March 1597

- Lords Justices: 29 October 1597

- Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. 12 March 1599

- Lords Justices: 24 September 1599

- The Lord Mountjoy (Lord Deputy): 21 January 1600

Under the House of Stuart

- The Lord Mountjoy (Lord Lieutenant): 25 April 1603

- Arthur Chichester (1563-1625) Baron Chichester Of Belfast : 15 October 1604

- Sir Oliver St John: 2 July 1616

- Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland: 18 September 1622

- Lords Justices: 8 August 1629

- The Viscount Wentworth later The Earl of Strafford: 3 July 1633 (executed May 1641)

- The Earl of Leicester (Lord Lieutenant): 14 June 1641

- The Marquess of Ormonde: 13 November 1643 (appointed by the king)

- Viscount Lisle: 9 April 1646 (appointed by parliament, commission expired 15 April 1647)

- The Marquess of Ormonde: 30 September 1648 (appointed by the King)

During the Interregnum

- Oliver Cromwell (Lord Lieutenant): 22 June 1649

- Henry Ireton (Lord Deputy): 2 July 1650 (d. 20 November 1651)

- Charles Fleetwood (Lord Deputy): 9 July 1652

- Henry Cromwell (Lord Deputy): 17 November 1657

- Henry Cromwell (Lord Lieutenant): 6 October 1658, resigned 15 June 1659

- Edmund Ludlow (Commander-in-Chief): 4 July 1659

Under the House of Stuart

- The Duke of Albemarle: June 1660

- The Duke of Ormonde: 21 February 1662

- Thomas Butler (1634-1680) 6th Earl of Ossory (Lord Deputy): 7 February 1668

- The Lord Robartes: 3 May 1669

- The Lord Berkeley of Stratton: 4 February 1670

- The Earl of Essex: 21 May 1672

- The Duke of Ormonde: 24 May 1677

- The Earl of Arran: 13 April 1682

- The Duke of Ormonde: 19 August 1684

- Lords Justices: 24 February 1685

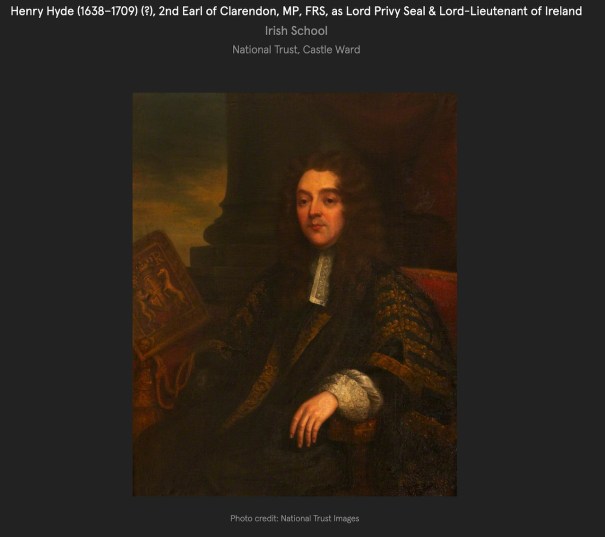

- Henry Hyde (1638-1709 (?)) 2nd Earl of Clarendon: 1 October 1685

- Richard Talbot (1630-1691), Duke of Tyrconnell (Lord Deputy): 8 January 1687

- King James II himself in Ireland: 12 March 1689 – 4 July 1690

- King William III himself in Ireland: 14 June 1690

- Lords Justices: 5 September 1690

- The Viscount Sydney: 18 March 1692

- Lords Justices: 13 June 1693

- Algernon Capell 1670-1710 2nd Earl of Essex (Lord Deputy): 9 May 1695

- Lords Justices: 16 May 1696

- The Earl of Rochester: 28 December 1700

- The Duke of Ormonde: 19 February 1703

- The Earl of Pembroke: 30 April 1707

- The Earl of Wharton: 4 December 1708

- The Duke of Ormonde: 26 October 1710

- The Duke of Shrewsbury: 22 September 1713

Under the House of Hannover

- The Earl of Sunderland: 21 September 1714

- Lords Justices: 6 September 1715

- The Viscount Townshend: 13 February 1717

- The Duke of Bolton: 27 April 1717

- The Duke of Grafton: 18 June 1720

- The Lord Carteret: 6 May 1724

- The Duke of Dorset: 23 June 1730

- The Duke of Devonshire: 9 April 1737

- The Earl of Chesterfield: 8 January 1745

- The Earl of Harrington: 15 November 1746

- The Duke of Dorset: 15 December 1750

- William Cavendish (1720-1764) 4th Duke of Devonshire: 2 April 1755

- The Duke of Bedford: 3 January 1757

- The Earl of Halifax: 3 April 1761

- The Earl of Northumberland: 27 April 1763

- The Viscount Weymouth: 5 June 1765

- The Earl of Hertford: 7 August 1765

- The Earl of Bristol: 16 October 1766 (did not assume office)

- The Viscount Townshend: 19 August 1767

- The Earl Harcourt: 29 October 1772

- The Earl of Buckinghamshire: 7 December 1776

- The Earl of Carlisle: 29 November 1780

- The Duke of Portland: 8 April 1782

- The Earl Temple: 15 August 1782

- The Earl of Northington: 3 May 1783

- The Duke of Rutland: 12 February 1784

- The Marquess of Buckingham: 27 October 1787

- The Earl of Westmorland: 24 October 1789

- The Earl FitzWilliam: 13 December 1794

- The Earl Camden: 13 March 1795

- The Marquess Cornwallis: 14 June 1798

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

Under the House of Hannover

- The Earl of Hardwicke: 27 April 1801

- The Earl of Powis: 21 November 1805 (did not serve)

- The Duke of Bedford: 12 March 1806

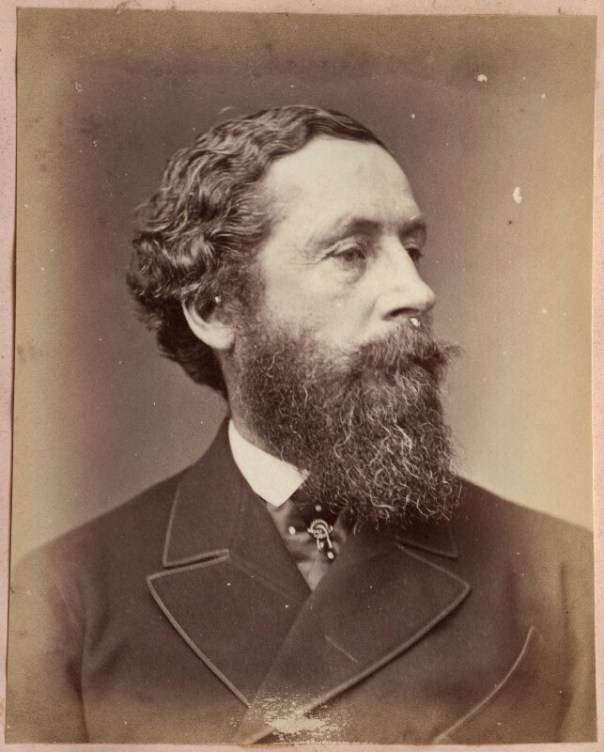

- Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond: 11 April 1807

- The Viscount Whitworth: 23 June 1813

- The Earl Talbot: 3 October 1817

- The Marquess Wellesley: 8 December 1821

- Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey (1768-1854): 27 February 1828

- The Duke of Northumberland: 22 January 1829

- Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey (1768-1854): 4 December 1830

- Richard Colley Wellesley (1760-1842), 2nd Earl of Mornington and 1st Marquess Wellesley: 12 September 1833

- The Earl of Haddington: 1 January 1835

- The Earl of Mulgrave: 29 April 1835

- Viscount Ebrington: 13 March 1839

- The Earl de Grey: 11 September 1841

- The Lord Heytesbury: 17 July 1844

- John William Brabazon Ponsonby (1781-1847) 4th Earl of Bessborough, County Kilkenny: 8 July 1846

- The Earl of Clarendon: 22 May 1847

- The Earl of Eglinton: 1 March 1852

- The Earl of St Germans: 5 January 1853

- The Earl of Carlisle: 7 March 1855

- The Earl of Eglinton: 8 March 1858

- The Earl of Carlisle: 24 June 1859

- The Lord Wodehouse: 1 November 1864

- The Marquess of Abercorn: 13 July 1866

- The Earl Spencer: 18 December 1868

- James Hamilton (1811-1885) 1st Duke of Abercorn: 2 March 1874

- The Duke of Marlborough: 11 December 1876

- The Earl Cowper: 4 May 1880

- The Earl Spencer: 4 May 1882

- The Earl of Carnarvon: 27 June 1885

- The Earl of Aberdeen: 8 February 1886

- Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart (1852-1915), 6th Marquess of Londonderry: 3 August 1886

- The Earl of Zetland: 30 July 1889

- The Lord Houghton: 18 August 1892

- The Earl Cadogan: 29 June 1895

Under the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (later Windsor)

- The Earl of Dudley: 11 August 1902

- The Earl of Aberdeen: 11 December 1905

- The Lord Wimborne: 17 February 1915

- The Viscount French: 9 May 1918

- The Viscount FitzAlan of Derwent: 27 April 1921

[1] https://repository.dri.ie/

[2] p. 8, Marnham, Niamh. An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of Dublin South City. Published by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 2017.

[3] https://www.archiseek.com/2010/1204-dublin-castle/

[4] p. 6, Marnham, Niamh. An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of Dublin South City. Published by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 2017.

[3] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com

[10] p. 9, Marnham, Niamh. An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of Dublin South City. Published by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 2017.