Battle of the Boyne site and visitor centre, Oldbridge Hall, County Meath.

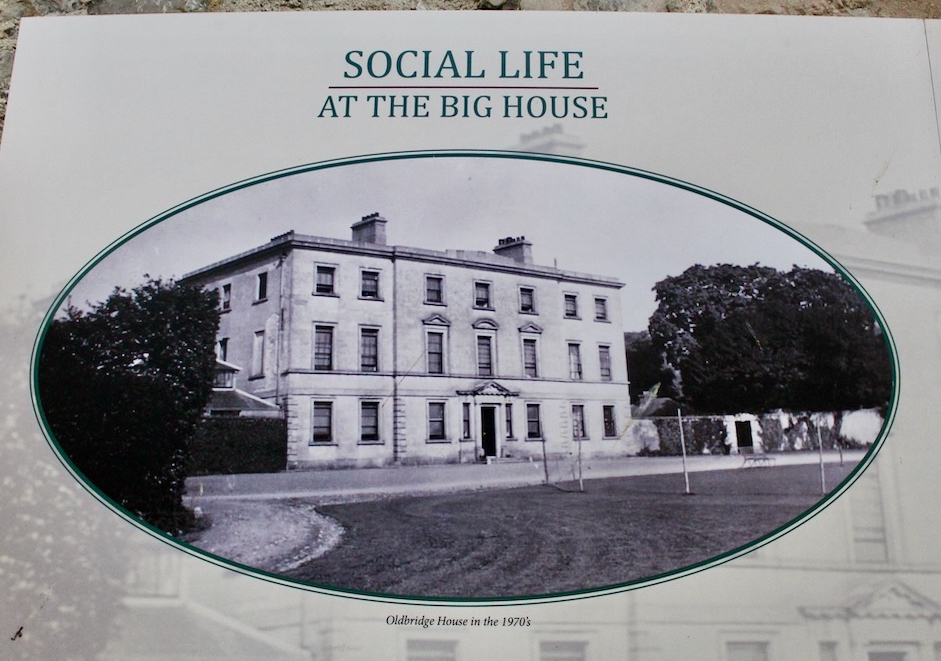

The Battle of the Boyne museum is housed in Oldbridge Hall, which is built on the site where the battle of the took place. The house is maintained by the Office of Public Works.

https://heritageireland.ie/places-to-visit/battle-of-the-boyne-visitor-centre-oldbridge-estate/

Stephen and I have a personal connection, as Oldbridge was built by the Coddington family, and a daughter from the house, Elizabeth Coddington (1774-1857), married Stephen’s great great grandfather Edward Winder (1775-1829).

The Battle of the Boyne, 1st July 1690, was just one of several battles that took place in Ireland when the rule of King James II was challenged by his son-in-law, a Dutch Protestant Prince, William of Orange. James II was Catholic, and he attempted to introduce freedom of religion, but this threatened families who had made gains under the reformed Protestant church. When James’s wife gave birth to a male heir in 1688, many feared a permanent return to Catholic monarchy and government. In November 1688, seven English lords invited William of Orange to challenge the monarchy of James II. William landed in England at the head of an army and King James feld to France and then to Ireland. William followed him over to Ireland in June 1690.

There were 36,000 men on the Williamite side and 25,000 on the side of King James, the Jacobites. William’s army included English, Scottish, Dutch, Danes and Huguenots (French Protestants). Jacobites were mainly Irish Catholics, reinforced by 6,500 French troops sent by King Louis XIV. Approximately 1,500 soldiers were killed at the battle.

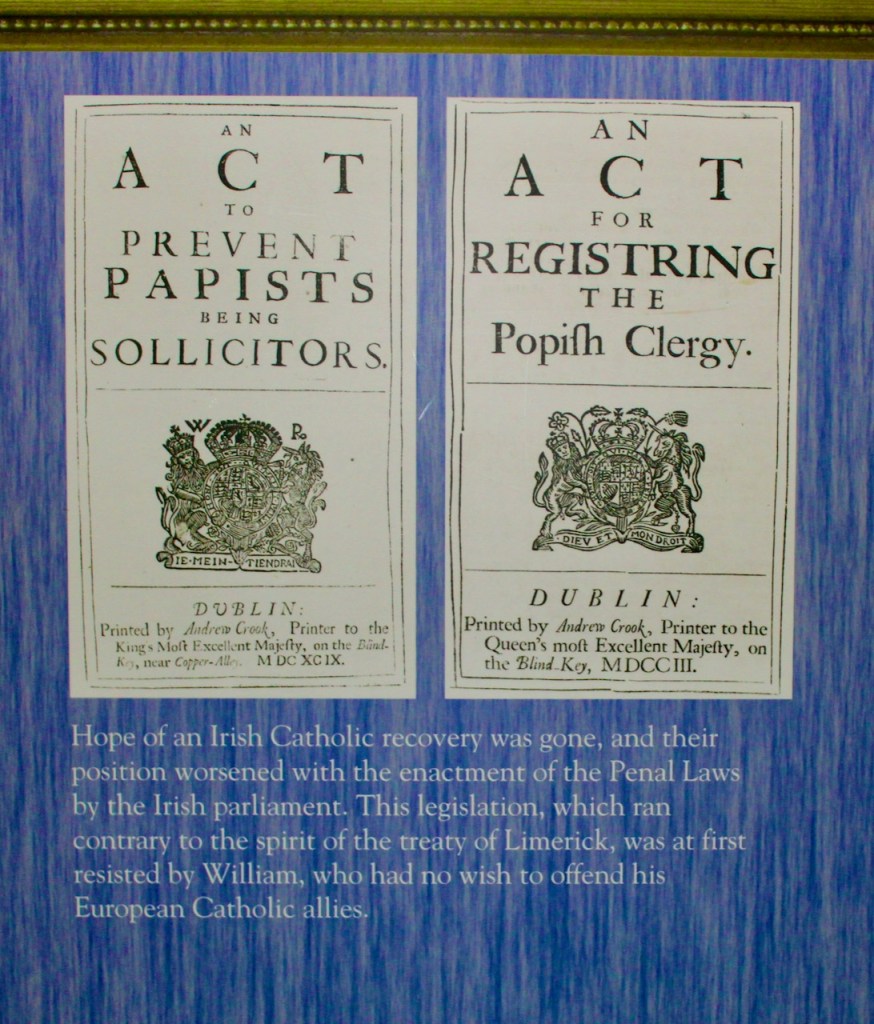

After winning the battle, William gained control of Dublin and the east of Ireland. However, the war continued until the Battle of Aughrim in July 1691, which led to the surrender at Limerick the following autumn. The surrender terms promised limited guarantees to Irish Catholics and allowed the soldiers to return home or to go to France. The Irish Parliament however then enacted the Penal Laws, which ran contrary to the treaty of Limerick and which William first resisted, as he had no wish to offend his European Catholic allies.

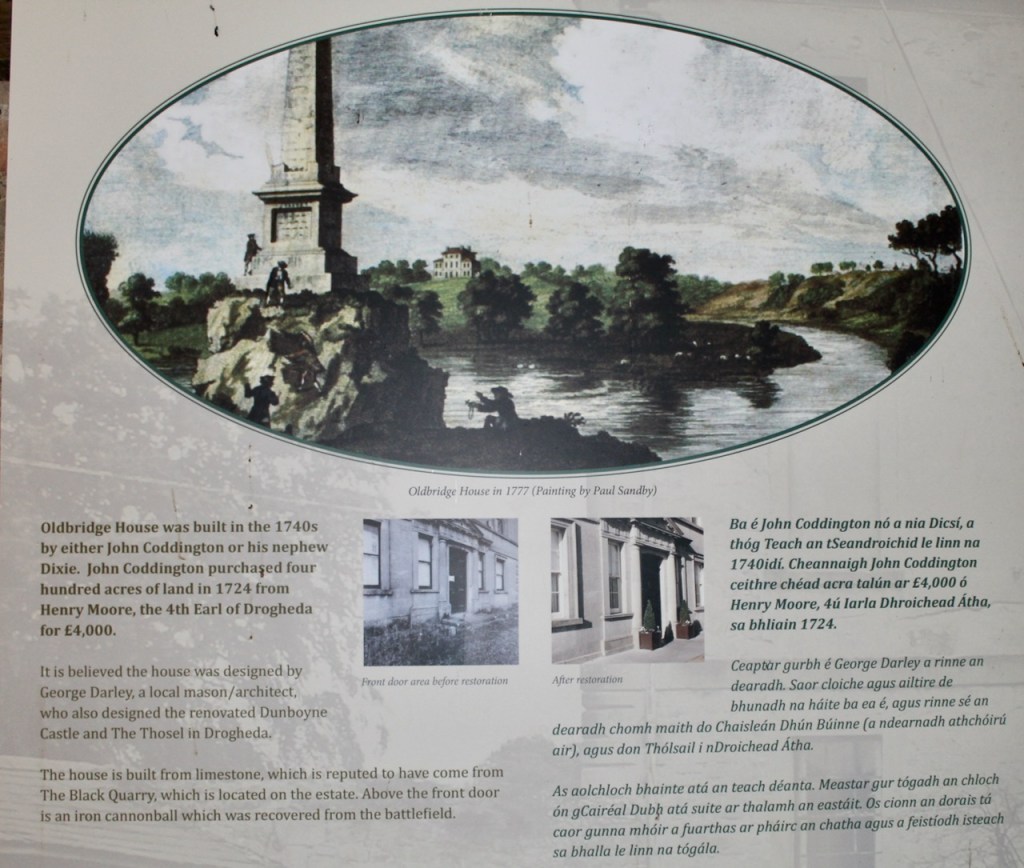

John Coddington (1691-1740) purchased the land in 1729 from Henry Moore the 4th Earl of Drogheda. John’s father Dixie (1665-1728) fought in the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 on the side of King William III. The unusual name “Dixie” comes from the maternal side, as Dixie’s father Captain Nicholas Coddington of Holm Patrick (now Skerries) in Dublin married as his second wife Anne Dixie, possibly a daughter of Sir Wolstan Dixie, 1st Baronet (1602-1682).

John married Frances Osbourne in 1710, and with the marriage came property in County Meath including Tankardstown. Tankardstown House is a boutique hotel and a section 482 property (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/11/tankardstown-estate-demesne-rathkenny-slane-co-meath/ ). John Coddington served as High Sheriff of County Meath in 1725, before he acquired the property at Oldbridge.

John’s son, also named John, predeceased him, tragically drowning in the Boyne. In the Meath History Hub Noel French recounts a story about how a young woman refused to marry John because she dreamed that he would die, as he did, before the age of twentyone. [1] I have obtained most of my information in today’s entry from the wonderfully informative Meath History Hub website.

Noel French tells us that the office of High Sheriff had judicial, electoral, ceremonial and administrative functions and executed high court writs. The usual procedure for appointing the sheriff from 1660 onwards was that three persons were nominated at the beginning of each year from the county and the Lord Lieutenant then appointed his choice as High Sheriff for the remainder of the year. Often the other nominees were appointed as under-sheriffs. Members of the Coddington family held the position in 1725, 1754, 1785, 1798, 1843, 1848 and 1922. [see 1]

After John’s death in 1740 the house at Oldbridge was advertised for lease, described as the house, gardens and demesne, so the house must have been built by this time. [see 1] The property passed to John’s brother Nicholas’s son, Dixie Coddington (1725-1794).

I am confused about the date of construction. According to the notice for lease, a house stood at the site in 1740. Evidence that the current house was built around 1750 however was found in an inscription on piece of baseboard of a stair removed during repairs carried out in 1960s that reads: ‘ December 1836 Patrick Kelly of the City of Dublin / Put up these Staircases. / I worked at this building from April / till now. / 86 years from the first / Building of this house/ till now as we see by a stick like this found.’

In The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster, The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath (published in 1993), Casey and Rowan accept that the house was built around 1750. They suggest that it may have been designed by George Darley (1730-1817), due to affinities with Dowth Hall nearby and to Dunboyne Castle.

The house is three storey with a plain ashlar frontage of seven bays, with the centre three slightly advanced. Christine Casey and Alistair Rowan tell us in The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster, The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath (published in 1993) that the house was originally designed as a three bay three storey block with low single-storey wings, and the upper stories of the wings were added later. [2]

In the early nineteenth century two floors were added to each wing. Casey and Rowan tell us that this was apparently carried out by Frederick Darley (1798-1872).

Quadrant walls link the house to its park, with rusticated doors.

It has a centrally located tripartite doorcase with pilasters surmounted by a closed pediment, which holds a canonball from the fields of the Battle of the Boyne. It has a string course between ground and first floors and sill course to first floor, and three central windows on first floor with stone architraves. [3]

Dixie Coddington (1725-1794) married Catherine Burgh, daughter of Thomas Burgh (1696-1754) of Burgh (or Bert) house in County Kildare. Burgh Quay in Dublin is named after a sister of Thomas Burgh’s, Elizabeth, who was the wife of the Speaker of the House in Ireland, Anthony Foster. Thomas Burgh’s uncle, another Thomas Burgh (1670-1730), was Surveyor General and architect.

On 13 April 1757 Dixie Coddington of Oldbridge sold Tankardstown. [see 1]

Dixie Coddington served as MP for Dunleer, County Louth. He and his wife had several daughters who all died in infancy, and no son, so Oldbridge passed to his brother, Henry Coddington (1728-1816). Dixie had previously leased Oldbridge to his brother, and has spent most of his life living in Dublin on Raglan Road. [see 1]

Henry Coddington (1728-1816) was father to Stephen’s ancestor Elizabeth. Henry was a barrister, and served as MP for Dunleer, County Louth, and he married Elizabeth Blacker from Ratheskar, County Louth. He served as High Sheriff for County Louth, then for County Meath, and was Deputy Serjeant-at-Arms between 1791 and 1800. He served as Justice of the Peace also for Counties Louth and Meath.

Henry and Elizabeth’s son Nicholas (1765-1837) followed in his father’s footsteps, and served as MP for Dunleer before the Act of Union in 1800, and also served as high sheriff for counties Louth and Meath. Nicholas and his son, Henry Barry, carried out a number of improvements on the estate. The house was re-modelled in the 1830s to the drawing of Frederick Darley. [see 1]

The Oldbridge Estate then passed to Henry-Barry Coddington, son of Nicholas. Henry-Barry Coddington was born on May 22nd in the year 1802; he was the eldest surviving son of Nicholas Coddington and Laetitia Barry. Henry Barry took a Grand Tour of Europe and kept a diary. He married Maria Crawford, eldest daughter of William Crawford of Bangor Co. Down in 1827.

Noel French tells us of Maria Crawford’s father and his role in tenant land rights:

“William Sharman Crawford, was the owner of 5,748 acres in County Down … as well as 754 acres at Stalleen in County Meath. William Sharman Crawford took an active interest in politics. He is best known for his advocacy of Tenant Right – the Ulster Custom which gave a tenant greater security through the three “f”s: fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale of goodwill. Crawford called this “The darling object of my heart”. This idea was not popular with other landlords, but Crawford remained a strong advocate of it for the rest of his life. In 1843 Crawford managed to persuade Sir Robert Peel, the Conservative prime minister, to establish the Devon Commission to investigate the Irish land question. Tenant right, the subject of eight successive bills drafted by Sharman Crawford, was eventually conceded in the Land Acts of 1870 and 1881.”

Despite the admirable work of his father-in-law, Henry-Barry Coddington was a slave owner. He inherited an estate in Jamaica from his great uncle, Fitzherbert Richards. The estate, Creighton Hall in the parish of St. Davids in Jamaica, had previously belonged to Fitzherbert’s brother Robert Richards. The estate was 1165 acres. 399 acres was planted with sugar cane in 1790. The plantation produced sugar, rum, molasses, cotton, ginger, coffee, cocoa and pimento. [see 1]

In A Parliamentary Return of 1837-38, which listed names of those who claimed a loss of “property” after slavery was abolished in 1834, Henry-Barry Coddington was recorded as the `Master` to 235 enslaved individuals. It seems, however, that Coddington was unsuccessful in his claim for compensation.

The property at Oldbridge passed to a son, John Nicholas Coddington (1828-1917) and then to his son Arthur Francis by his first wife, Lelia Jane Naper (d. 1879) of nearby Loughcrew House, a Section 482 property (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/21/loughcrew-house-loughcrew-old-castle-co-meath/ ).

Oldbridge House was occupied by the National Army in July 1922. In 1923 Arthur F. Coddington of Oldbridge brought a claim against the government for damages done by the National Army forces when they occupied Oldbridge House. The repairs included slates, plumbing, painting and six trees felled.[see 1]

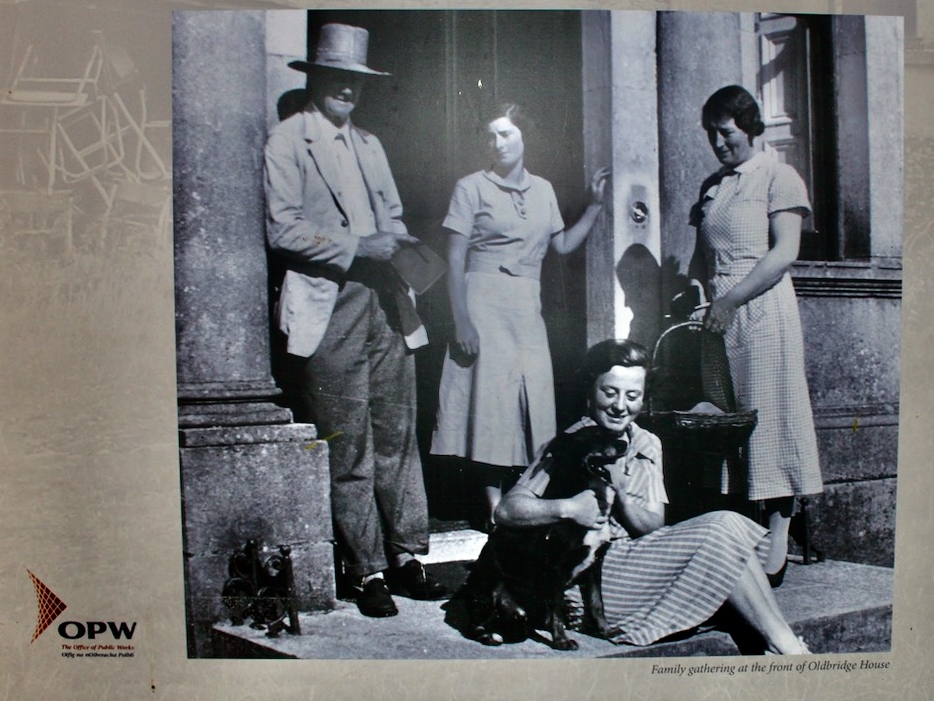

Arthur’s son Dixie fought in World War II then returned to live in Oldbridge, where he began a commercial market gardening business, and where he trained young people in horticulture.

The Meath History hub tells us that in 1982 a gang broke into Oldbridge House and stole £600,00 in antiques. Two years later, Dixie’s son Nicholas and his wife were held at gunpoint for eleven terrifying hours in their house. Among the items stolen was an eight-foot picture of King William III, dating back to 1700, a number of landscape paintings and a number of family portraits. The haul included items that had been recovered from the robbery two years previously. In 1984 Nicholas Coddington put the house and contents up for sale.

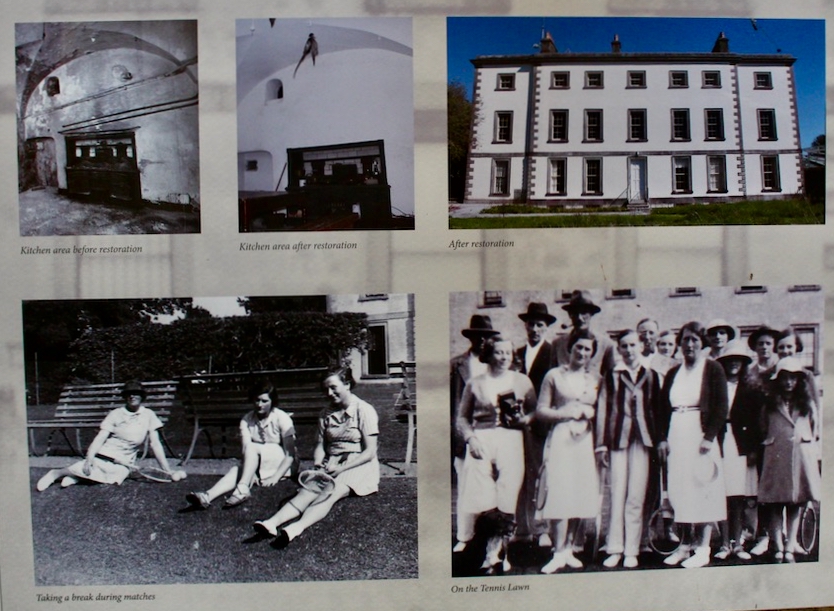

Oldbridge House was purchased by the state in 2000 as part of the Good Friday Peace Agreement, and renovation began.

To the left of the house there is a cobble stone stable yard with fine cut stable block. This originally contained coach houses, stables, tack and feed rooms.

To the right of the house is a small enclosed courtyard which contains the former butler’s house.

The gardens of Oldbridge House have been restored, with an unusual sunken octagonal garden, peach house, orchard and herbaceous borders, with a tearoom in the old stable block. Throughout the year outdoor theatre, workshops and events such a cavalry displays and musket demonstrations help to recreate a sense of what it might have been like on that day in July 1690.

[1] https://meathhistoryhub.ie/coddingtons-of-old-bridge/

[2] p. 446. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan, The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster, The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, UK, 1993.