Open dates in 2025: June 1-2, 4-8, 11-15, 18-22, 25-29, July 2-6, 9-13, 16-20, 23-27, 30-31, Aug 1-4, 6-10, 13-24, 27-31, 10.30am-6pm

Fee: adult €16, OAP/student €14, child €8, tour groups of over 30 persons who pay in advance receive a discount

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

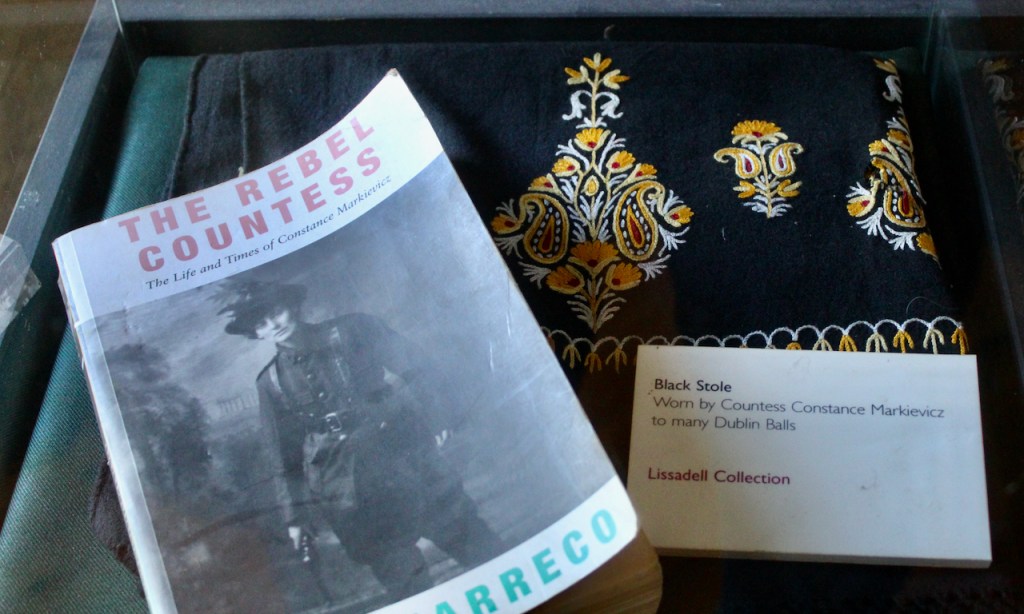

We visited Lissadell during Heritage Week 2022. I had been looking forward to seeing it as it has some amazing internal Classical architecture. It is most famous as the birthplace of Constance Markievicz, née Gore-Booth, the first woman senator in Ireland and fighter in the 1916 uprising, and also more recently as the host of a concert of Leonard Cohen. It was only sold out of the Gore-Booth family in 2004.

It was built in 1830-35 for Robert Gore-Booth (1805-1876), 4th Baronet, to the Greek Revival design of Manchester architect Francis Goodwin (1784-1835). It replaced an earlier house nearer the shore which itself replaced an old castle. It is a nine-bay two-storey over basement house built of Ballisodare limestone. [1]

The entrance front (north) elevation has a three-bay pedimented central projection flanked by three-bay side sections. When one approaches on the path one can see that the lower storey is open to the east and west to form a porte-cochere. The house was described by Maurice Craig as being ‘…distinguished more by its solidity than by its suavity and more by its literary associations than by either.’ I find the crafted stone and the massive squareness of it beautiful.

The east elevation which faces the sea has a five-bay central section between two-bay projections. The five-bay section contains a three-bay central breakfront with tall framing pilasters. Above the upper floor windows is a stepped stone feature that runs around three sides of the house.

Other former residents of the house deserve to be as famous as Constance.

Dermot James in his book The Gore-Booths of Lissadell tells us that the Gore-Booths are descended from Paul Gore of Manor Gore, County Donegal. He was MP for Ballyshannon in Donegal, and was created 1st Baronet Gore, of Magherabegg, County Donegal in 1621/22. He married a niece of the 1st Earl of Strafford, Isabella Wickliffe.

Paul Gore of Manor Gore had seven sons, and all married well. His oldest son, Ralph, 2nd Baronet, became the ancestor of the earls of Rosse, who are in Birr Castle [another section 482 property I visited]. Arthur, the second son, became the ancestor of the Earls of Arran, a family that subsequently inherited the very large Saunders Court estate near Ferrycarrig in County Wexford. He was MP for County Mayo and became 1st Baronet Gore, of Newtown Gore, Co. Mayo. A third son, Henry, married the eldest daughter of Robert Blaney of Monaghan and was the ancestor of the earls of Kingston. Two further sons settled in County Kilkenny, giving the family name to Goresbridge, and the seventh son settled in County Mayo and, according to a memorial tablet in Killala Cathedral, married Ellinor St. George of Carrick, County Leitrim, and he died at his residence, Newtown Gore, later named Castle Gore and Deel Castle, near Killala, County Mayo in 1697.

The fourth son, Francis Gore (1612-1712), lived in Ardtarman, County Sligo, which still stands and has been renovated for habitation and self-catering accommodation. [2]

The front door is under the tall porte-cochere, which has a curved painted ceiling and massive wooden doors.

Francis Gore married Anne Parke of Parkes Castle in Leitrim – see my entry on OPW sites in Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/10/31/office-of-public-works-properties-in-connaught-counties-leitrim-mayo-roscommon-and-sligo/

Dermot James tells us that Francis managed to keep on good terms with both the Cromwellians and Royalists during the Civil War, avoiding an engagement with either cause. After the Restoration of Charles II, he was rewarded with grants of land in Sligo, Mayo and Kilkenny, and in 1661 he was knighted and also became M.P. for Sligo. He settled at Ardtarmon, two miles west of Lissadell. He fought for the crown in Lieutenant-Colonel Coote’s Regiment.

Francis and Anne had a son, Robert (1645-1720). He married Frances Newcomen and they had a son, Nathaniel (1692-1737). He married Letitia (or Lettice) Booth, only daughter and heiress of Humphrey Booth, of Dublin. [3] She must have inherited quite a bit since later generations added her surname “Booth” to their surname. In fact, the prosperous Booth estates in the English midlands were added to the Sligo property.

Robert and Lettice named their son “Booth” (1712-1773). In 1760 Booth Gore was created 1st Baronet Gore of Lissadell, County Sligo.

Booth married Emilia Newcomen, daughter of Brabazon Newcomen, and they had several children. Their first son, also named Booth, who became 2nd Baronet, died unmarried, and his brother Robert Newcomen inherited and added Booth to his surname in 1804, when he succeeded as the 3rd Baronet.

Robert Newcomen Gore-Booth inherited in his 60s, and only then married Hannah Irwin from Streamstown, County Sligo (ninety years later this property became part of the Gore-Booth estate). Their daughter Anne married Robert King, 6th Earl of Kingston, son of the 1st Viscount Lorton.

The eldest son, Robert (1805-1876) became the 4th Baronet, and he built the house at Lissadell which we see now. He was Lord Lieutenant for County Sligo and also MP for Sligo.

The 4th Baronet married Caroline King, daughter of Robert Edward King, 1st Viscount Lorton, whom we came across in King House in County Roscommon. Sadly, she died the following year in 1828. Two years later he married Caroline Susan Goold, daughter of Thomas Goold (or Gould). Her sister Augusta married Edwin Richard Wyndham-Quin, 3rd Earl of Dunraven, of Adare Manor in Limerick.

According to Dermot James, “Henry Coulter described Lissadell before Robert inherited the estate as ‘wild and miserable and poor looking.’ But within a few decades Sir Robert had demonstrated ‘the immense improvement which may be made in the appearance of the country and the quality of the soil by the judicious expenditure of capital.’ Coulter continued, considering the estate to be “one of the most highly cultivated and beautiful in the United Kingdom… If the excellent example set by Sir Robert Booth as a resident country gentleman – living at home and devoting himself to the improvement of his property – were more generally followed by Irish landlords then indeed the cry of distress which is so often raised… would never more be heard, even in the west of Ireland.” [Henry Coulter, The West of Ireland published 1862]. [4]

Robert was in situ at the time of the Great Famine in the 1840s. He did send some tenants to North America, and was later criticised for the evictions, but on the whole he was a generous landlord. He ran a soup kitchen and provided seed for crops. When his first wife Caroline died the Sligo Journal called her “a ministering angel among the people, her charitie was unbounded and her exertions to relieve the wants and sufferings of the distressed excited the admiration of all classes” when “the dark clouds of pestilence and death covered the land.”

Dermot James writes: “If the exterior of Lissadell House is seen by some to be disappointingly plain, Goodwin’s design ensured that the entrance to the interior is all the more unexpected and dramatic. The visitor is met by a spectacularly high entrance hall decorated with Doric and Ionic columns from which there is an impressive staircase in Kilkenny marble with cast iron balustrade leading to the building’s most important feature, the great gallery, lit by sky-lights high above. On Goodwin’s plans, the gallery is marked as the music room, reflecting one of Sir Robert’s tastes, where an organ was installed. In the main, the house then remained largely unaltered for more than a century and a half.“

Mark Bence-Jones describes the entrance stair hall in his Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988) as a lofty two storey hall, partly top-lit, with square Doric columns below and Ionic columns above and double staircase of Kilkenny marble.

In the book Great Irish Houses, with forewards by Desmond FitzGerald, and Desmond Guinness published by IMAGE Publications in 2008, we are told that the scale of the stair hall is such that, unusually, a large fireplace was added to the return landing. The iron balusters are adorned with golden eagles.

Sir Robert took an interest also in the garden and Lord Palmerston of nearby Classiebawn would send him seeds from overseas. He sold some of the property in England and expanded his property in Ireland.

Dermot James tells us that when serving as MP Robert went regularly to London and brought his family and also servants. His servant Kilgallon wrote about the packing up: “They took all the silver plate. It was quite a business packing all up. They had boxes specially made for them. The housekeeper did not go as there was a housekeeper for the London house, a Mrs Tigwell. They took the first and second housemaids, house steward, groom chambers, under butler, and first and second footmen and steward’s room boy. All the other servants were put on board [reduced] wages [but] they were allowed milk and vegetables.” [6]

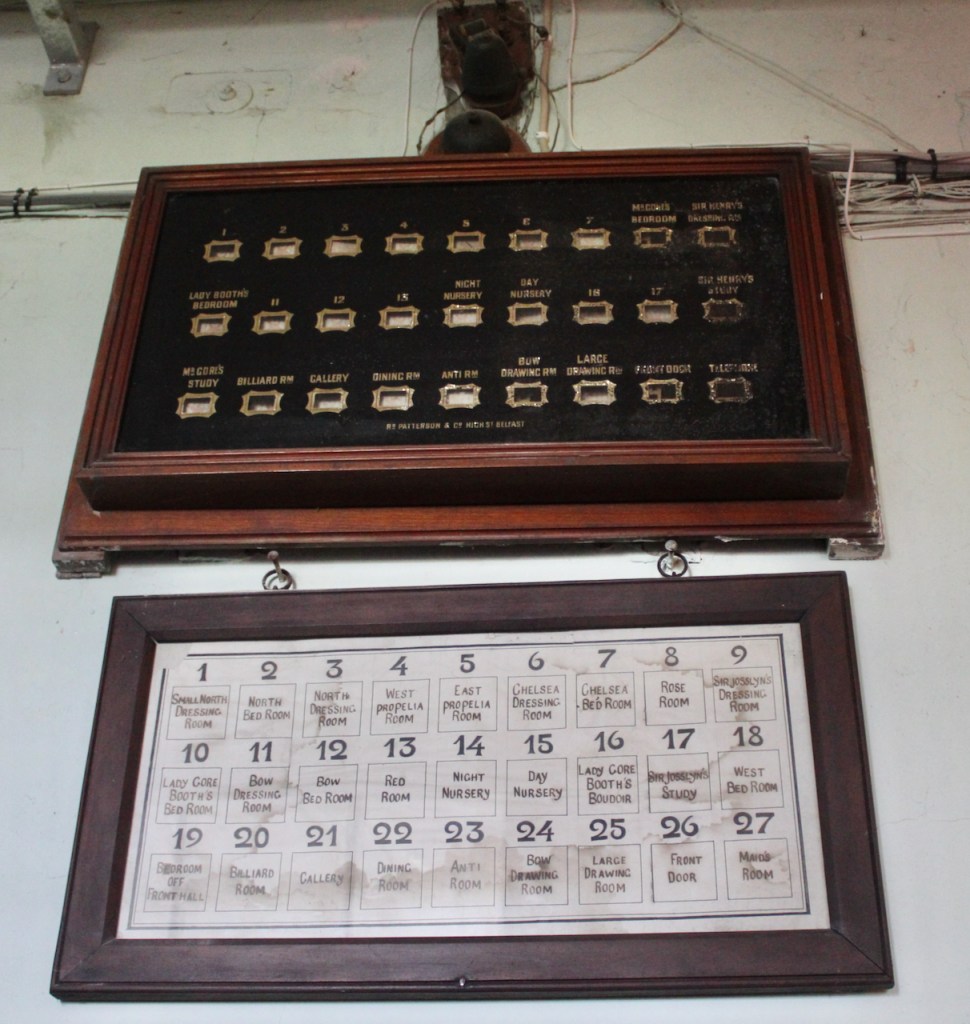

Kilgallon also described some details about how the Lissadell household was then being run, which is described by Dermot James: “The servants were managed by the house steward, Mr Ball, who engaged all the servants, paid their wages, and dismissed them when necessary. His duties included ordering all the wine for the house and acting as wine waiter at dinners. Ball supervised a small army of footmen, grooms, maids, etc. The groom chambers carved, and with the footmen, waited at all meals, despatched the post, opened the newspapers and ironed them. Their other duties included attending the hall door and polishing the furniture in the main rooms. One of the footmen was also the under-butler who kept the dinner silver in order and laid the dinner table, making sure that plates intended to be hot were kept warm in a special iron cupboard heated by charcoal kept outside the dining room door.”

The maids had to be up at 4am to prepare for carrying hot water to the bedrooms. There was a cook, pastry cook, kitchen maid, scullery maid and some kitchen boys. Kilgallon describes the meals, serving order and seating, and entertainment – there was a small dance in the servants hall once or twice a week, with beer and whiskey punch provided!

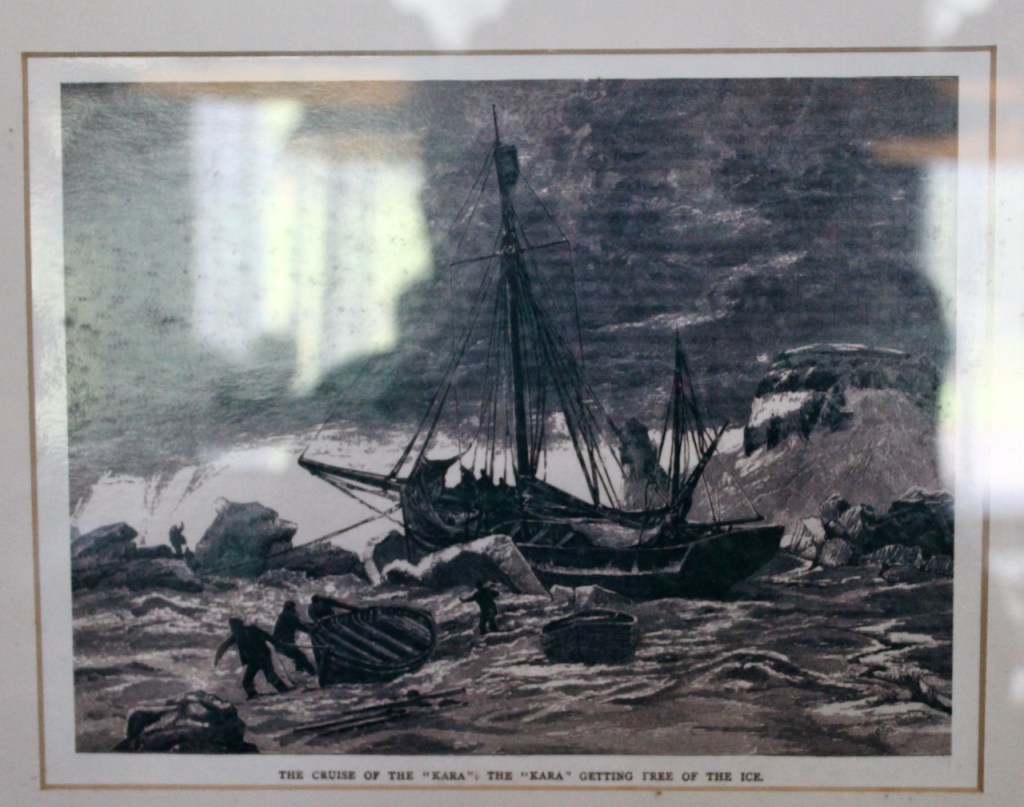

Henry William Gore-Booth (1843-1900) inherited in 1876 and became the 5th Baronet. He held the offices of High Sheriff of County Sligo, Deputy Lieutenant of County Sligo and Justice of the Peace for County Sligo. He was also a keen fisherman and Arctic explorer.

His sister Fanny Stella married Owen Wynne of nearby Hazelwood, County Sligo (which was designed by Richard Cassells and was recently owned by Lough Gill Distillery, until sold to American alcohol company Sazerac, which plans to save the house from dereliction).

From the entrance hall, we were brought by the tour guide into the Billiards Room full of Gore-Booth memorabilia, including Henry’s fishing equipment. Kilgallon stayed on for the next generation, and he accompanied Henry the 5th Baronet on all of his fishing adventures and Arctic explorations. Kilgallon became Sir Henry’s personal valet as well as his close companion and confidant. At one point he saved Henry from an attacking bear, and the bear was then stuffed and brought back to Lissadell. It used to stand in the front hall, alarming arriving guests!

The original wallpaper has been replaced by David Skinner, an expert on wallpapers of the great houses of Ireland, with hand-blocked period copies.

It is said that Sir Henry’s wife Georgina built the artificial lake at Lissadell in the vain hope that he might stay at home and fish in it, but as the harpoons and whale bones in the billiard room testify, Sir Henry continued to travel.

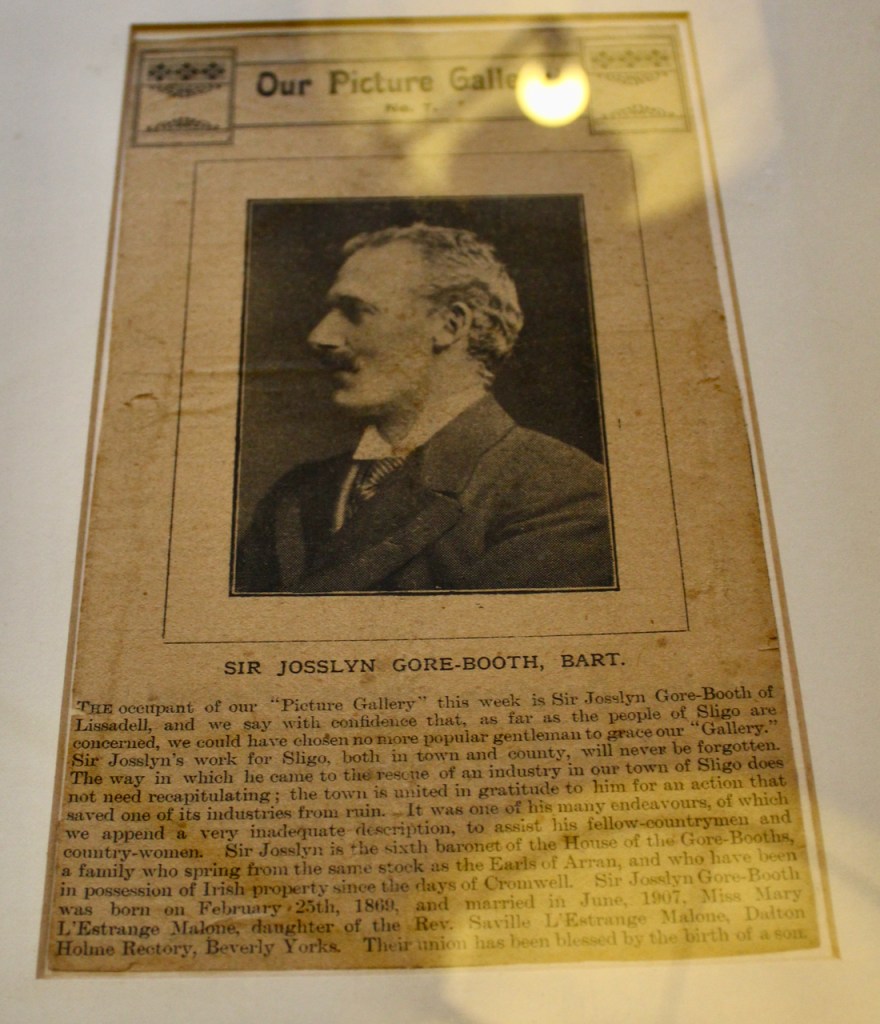

Robert was President of the Sligo Agricultural Society, and he and his eldest son founded three co-operative societies in the area. He also took over the Sligo Shirt Factory to prevent it from closing and made it flourish again. He was also involved in mining locally, and played a role in setting up the railway connecting Sligo with Enniskillen, subsequently becoming the company’s chairman. He also continued the oyster fishery his father had set up – his father was one of the pioneers in creating artificial oyster beds. Henry married Georgina Mary Hill, daughter of Colonel John Hill of Tickhill Castle, Yorkshire.

Upstairs is the music gallery. Mark Bence-Jones describes it as a vast apse-ended gallery (an apse is an area with curved walls at the end of a building, usually at the the east end of a church), lit by a clerestory (a clerestory is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level) and skylights, with engaged Doric piers along one side, and Ionic columns along the other. It was hard to capture in a photograph since we were on a tour.

In Great Irish Houses, forewards by Desmond FitzGerald and Desmond Guinness, we are told that the gallery is 65 foot long. It still has its original Gothic chamber organ, which was made by Hull of Dublin in 1812 and is pumped by bellows in the basement! Two Grecian gasoliers by William Collins, a renowned Regency maker of chandeliers, hang on chains from the ceiling. As late as 1846 Lissadell generated gas from its own gasometer.

Lissadell was the first house in Ireland to be lit by its own gas supply. This was produced in a plant installed by Sir Robert about a quarter of a mile to the west of the mansion, complete with a house for the manager in charge of the works.

A team led by Kevin Smith, from the internationally renowned Windsor House Antiques of London, undertook the major task of restoring the gasoliers.

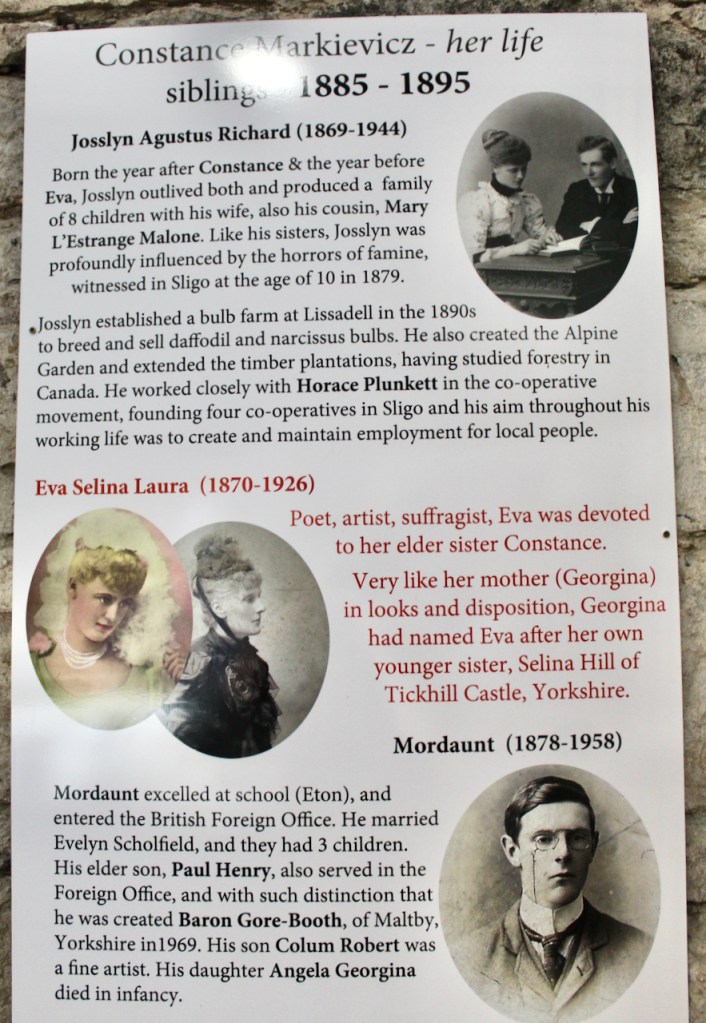

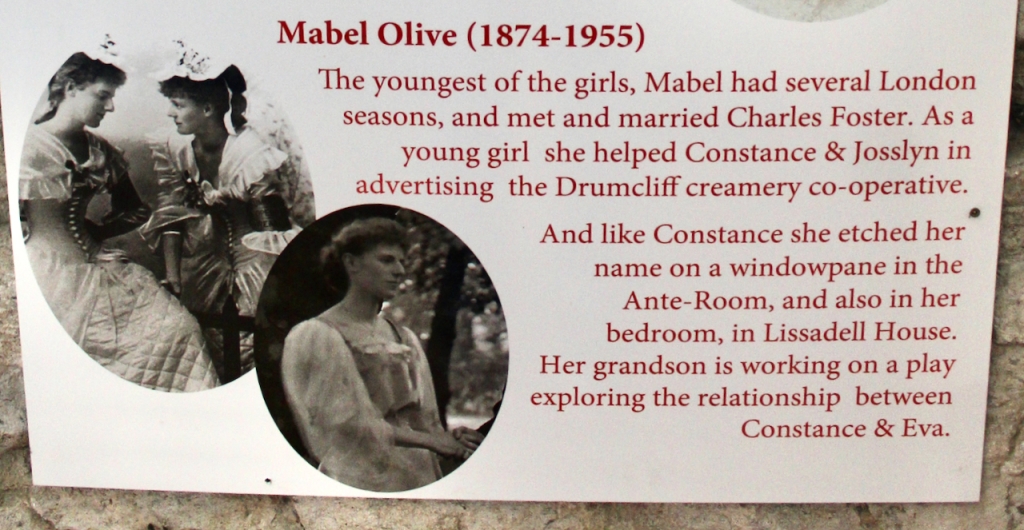

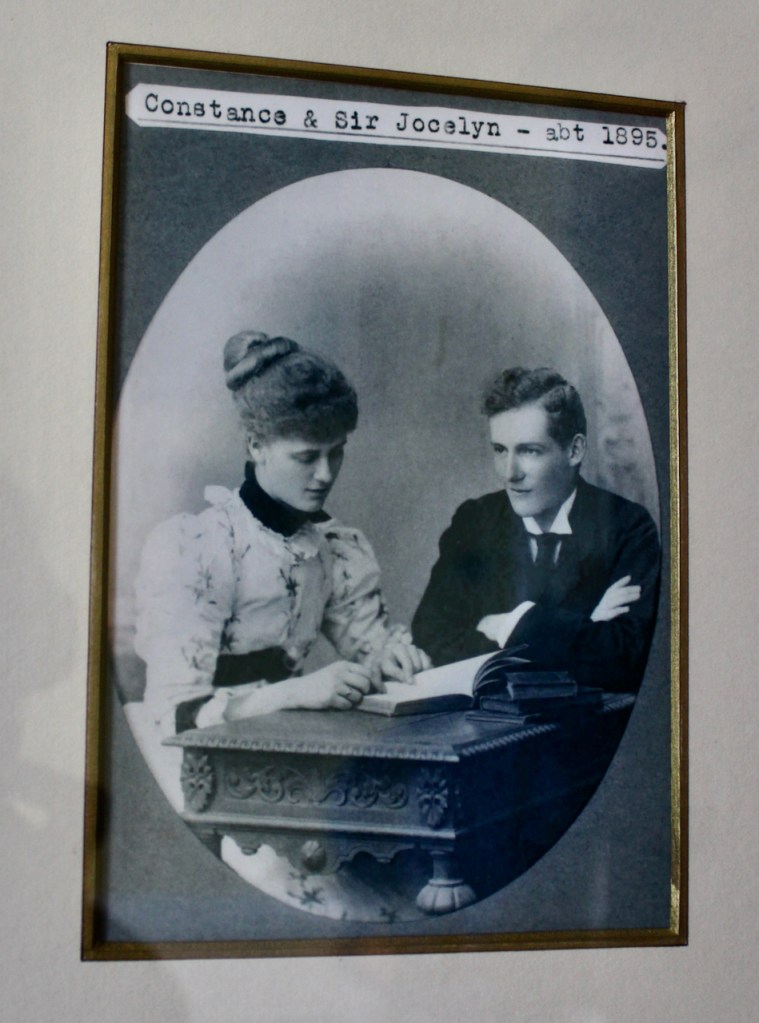

The 4th Baronet and Georgina Mary Hill had five children. The eldest son, Josslyn (1869-1944) was to inherit the property. There was a younger son, Mordaunt, and three daughters, Constance, Eva and Mabel.

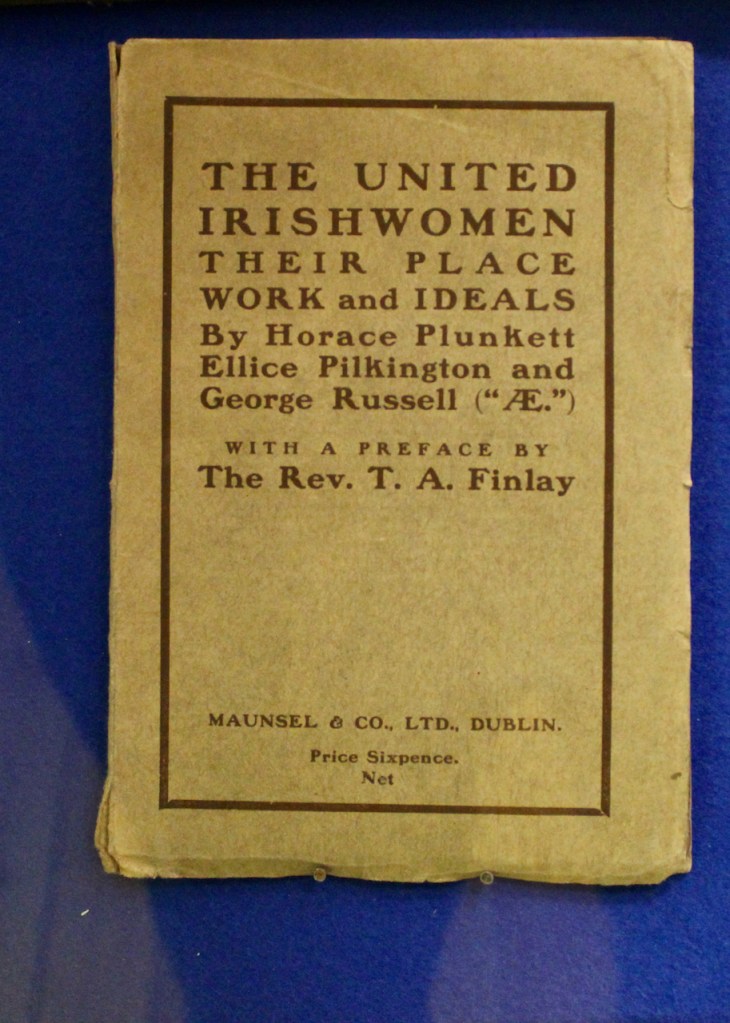

It was with Josslyn that Henry William set up the co-operatives. When Josslyn was young, he had socialist ideals, much like his sisters Eva and Constance. He joined Horace Plunkett in his efforts to help the farmers to help themselves, by cutting out the middle man. It took a while for farmers to trust the motivation of Plunkett and Gore-Booth in setting up the co-operatives, thinking that “no good thing could come from a man who was at once a Protestant, a landlord and a Unionist.” Catholic priests even denounced the co-operatives as a “Protestant plot.” Eventually, however, they flourished, and helped the farmers.

Josslyn continued to develop the estate, so that it became one of the most progressive and best run in Ireland.

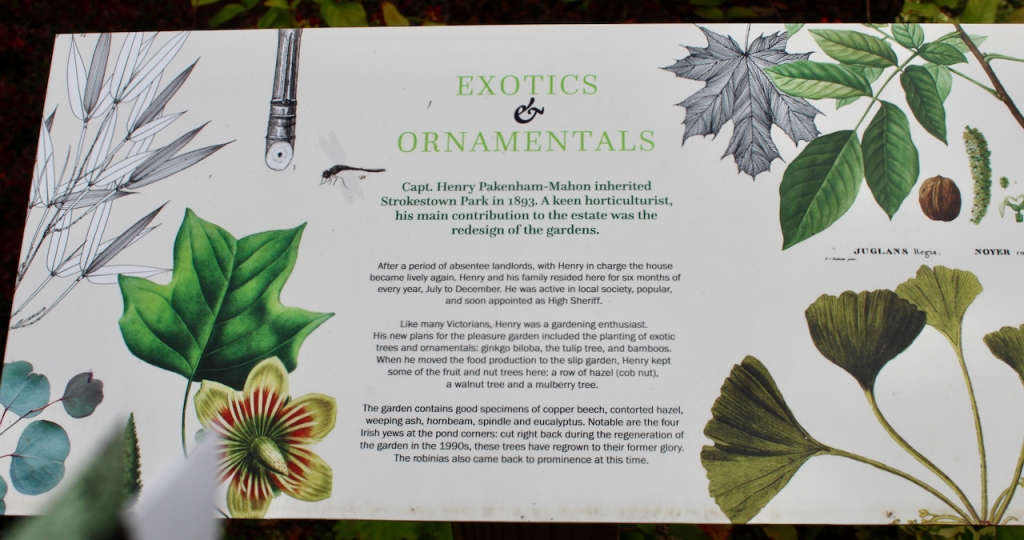

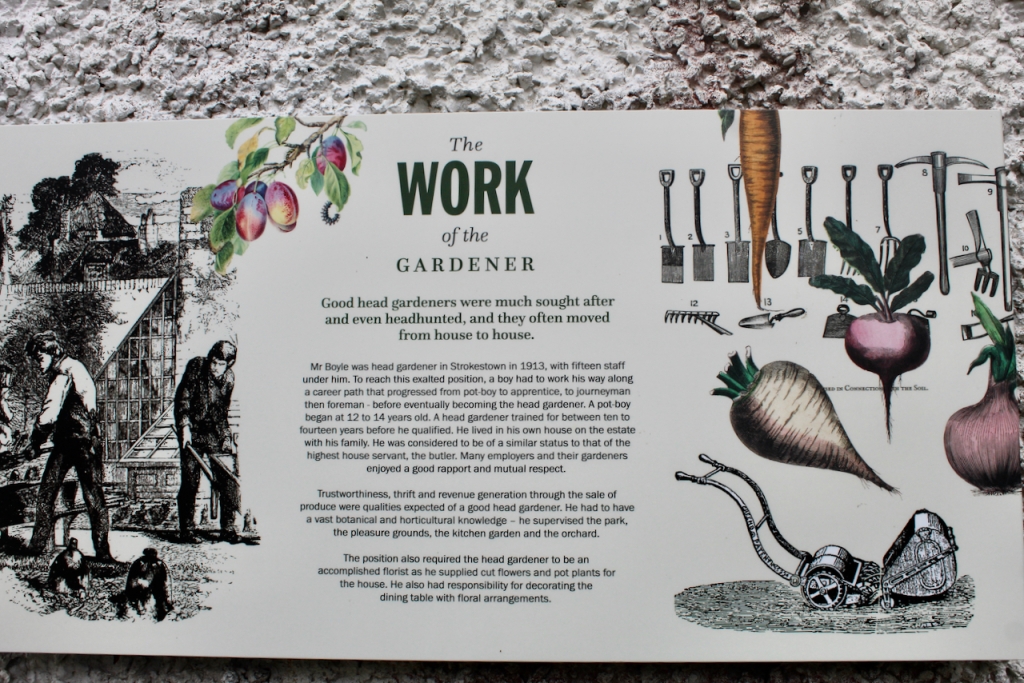

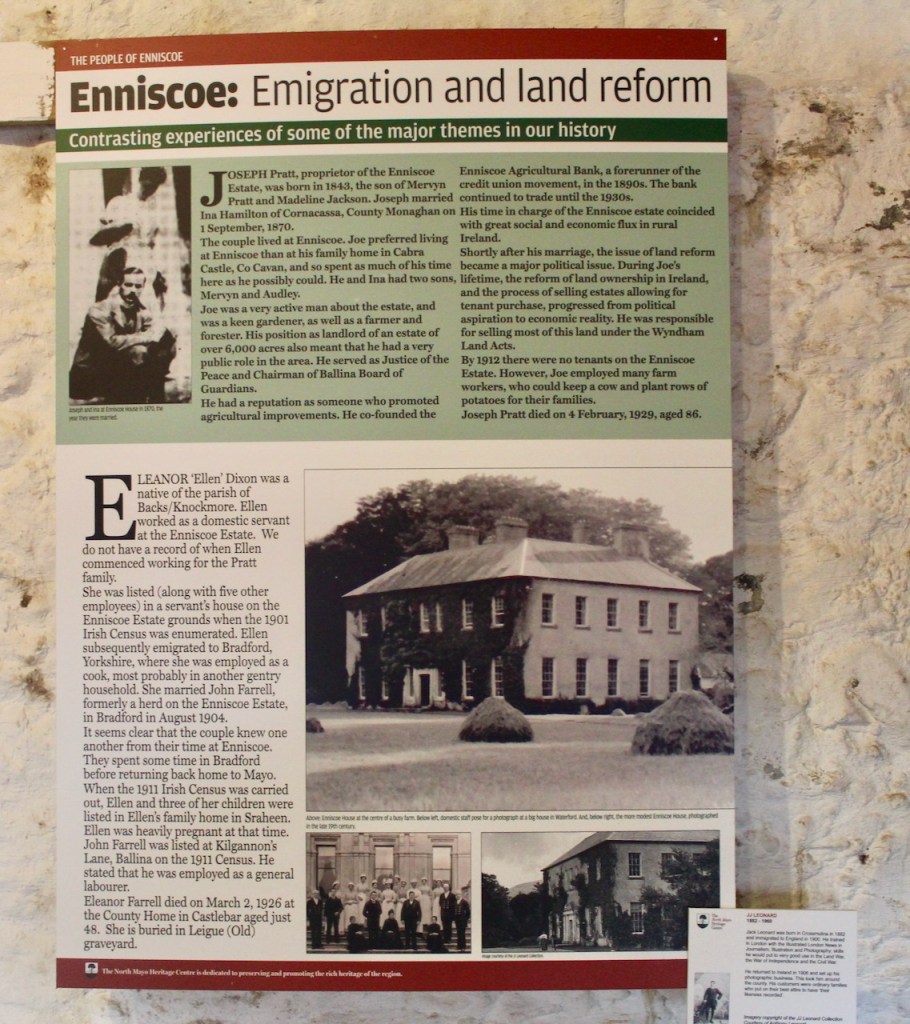

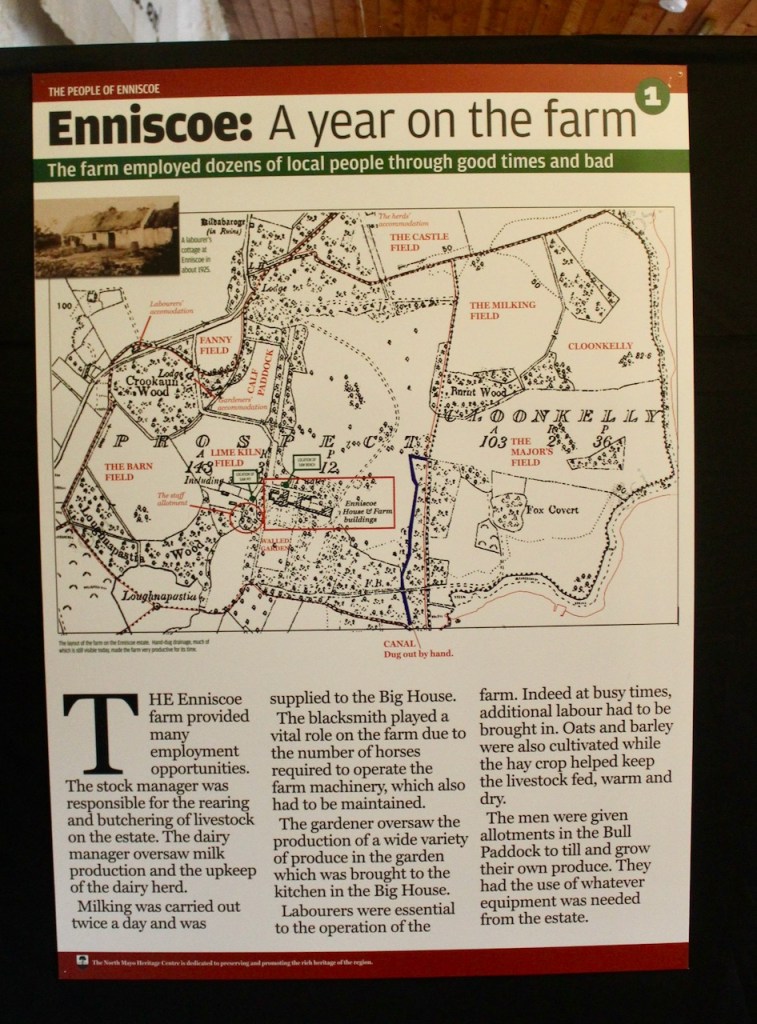

Josslyn was a keen gardener and plant breeder. At Lissadell he established one of the finest horticultural enterprises in Europe. By 1906, his gardens provided employment for more than 200 people. The head gardener, Joseph Sangster, became head gardener of the Royal Horticultural Society in England. An advocate of land reform, he let more than 1000 tenants buy out 28,000 acres of the property under the Wyndham Land Act of 1903. The final payments under the scheme were not received until the 1970s. Until he died in 1944, the estate was famous the world over for its varieties of old and new flowers. [7] The current owners are working to re-establish the gardens.

Next we enter a room that is in the bow of the house, and features in a poem by W. B. Yeats. Mark Bence-Jones tells us:

“The rather monumental sequence of hall and gallery leads to a lighter and more intimate bow room with windows facing towards Sligo Bay – the windows Yeats had in mind when he wrote, in his poem on Eva Gore-Booth and her sister, Constance Markievizc:

“The light of evening, Lissadell

Great windows open to the South.”

This room, and all other principal receptions rooms, have massive marble chimney-pieces in the Egyptian taste. The ante-room has a striped wallpaper of lovely faded rose.”

“In memory of Eva Gore Booth and Constance Markiewicz” This is the first part of this poem:

The light of evening, Lissadell,

Great windows open to the south,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

But a raving autumn shears

Blossom from the summer’s wreath;

The older is condemned to death,

Pardoned, drags out lonely years

Conspiring among the ignorant.

I know not what the younger dreams –

Some vague Utopia – and she seems,

When withered old and skeleton-gaunt,

An image of such politics.

Many a time I think to seek

One or the other out and speak

Of that old Georgian mansion, mix

pictures of the mind, recall

That table and the talk of youth,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.”

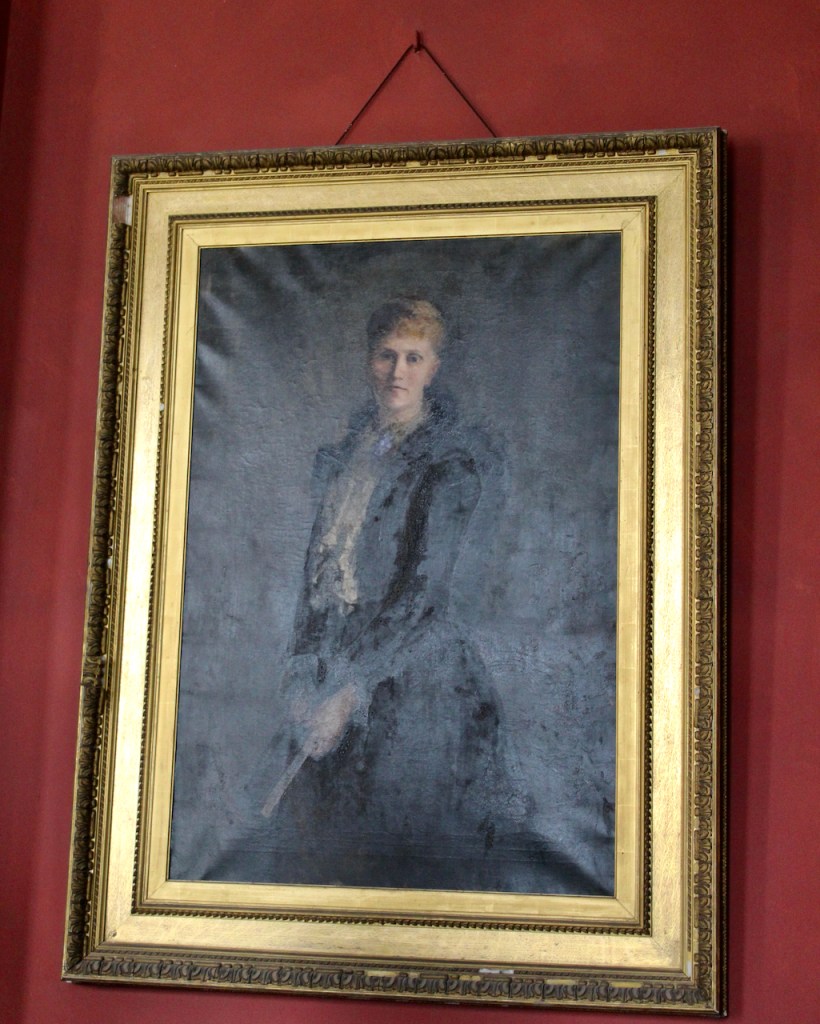

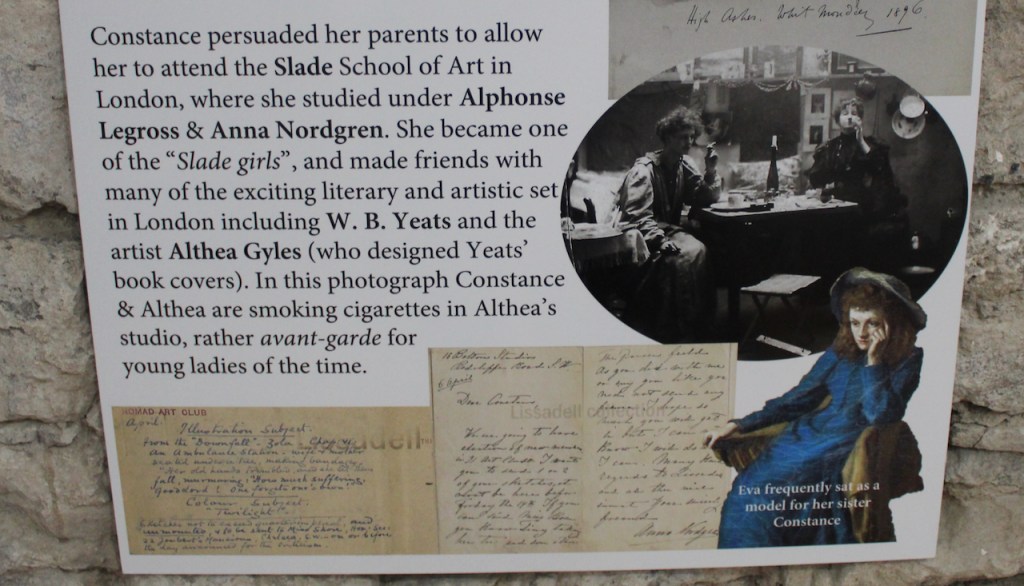

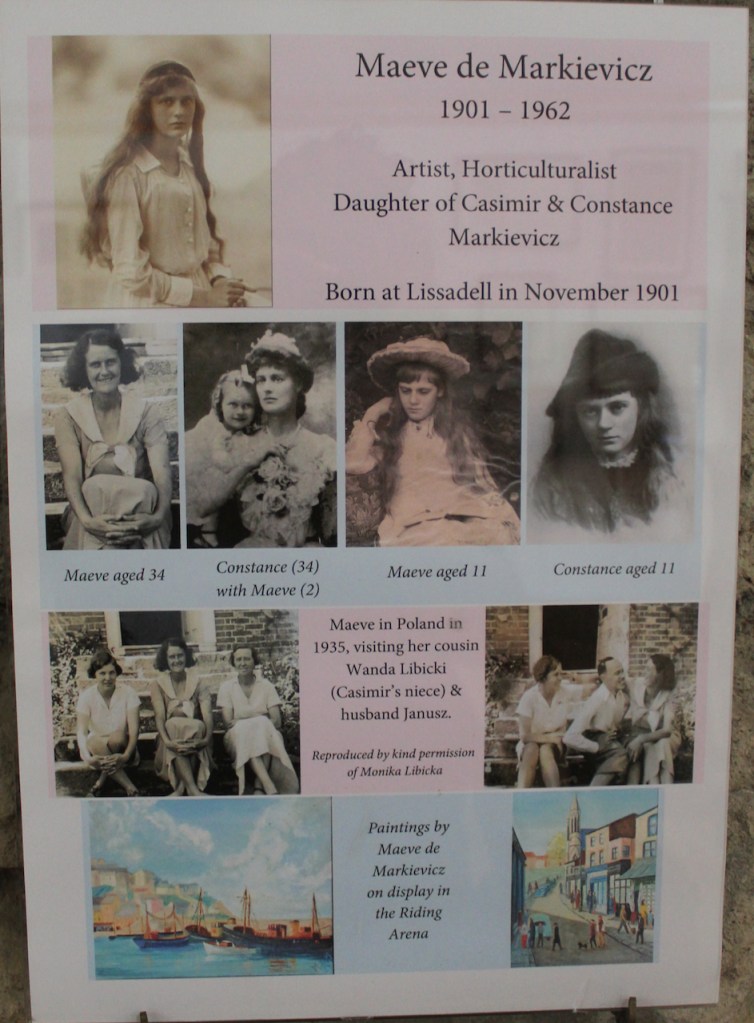

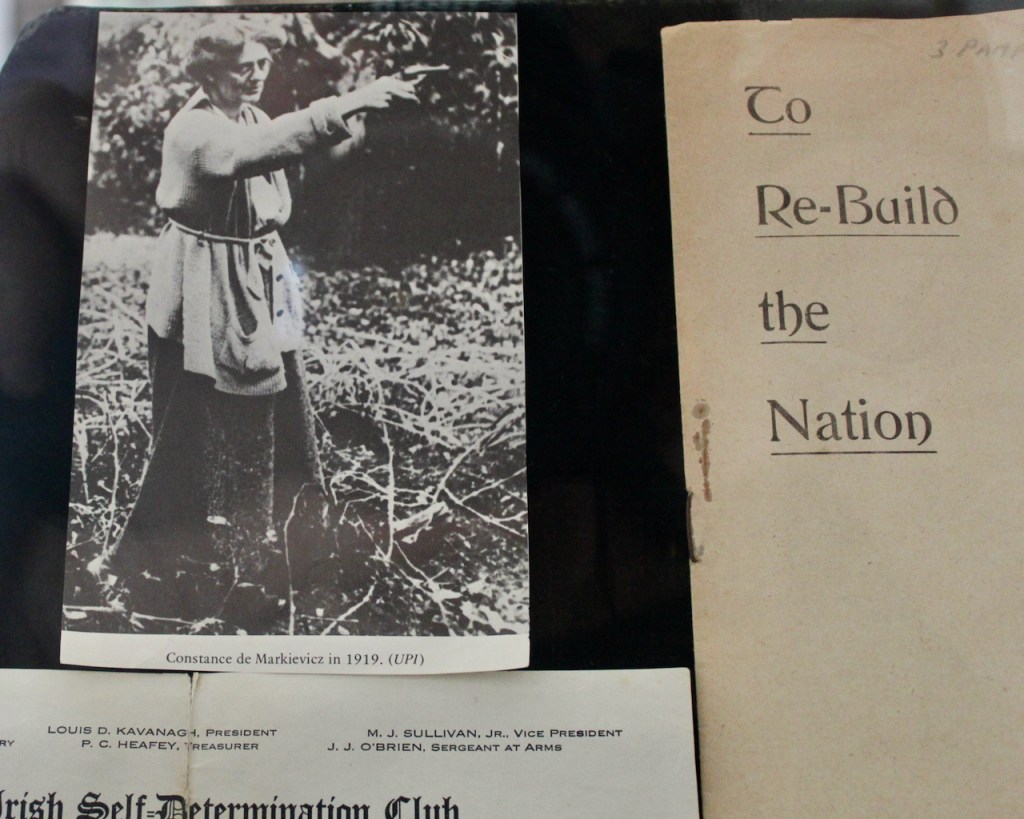

Constance went to art school in the Slade School of Art in London 1892-1894. She lived in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, where many of London’s bohemians and writers gathered: George Eliot had lived there, Whistler, Henry James and Erskine Childers. At the age of 25 went to Paris to continue her studies, and met and married a fellow artist, the Polish Casimir Markievicz. Many of Constance’s paintings still hang on the walls, as well as some work by Casimir. Their only child, Maeve Allys, was born in Lissadell in 1901.

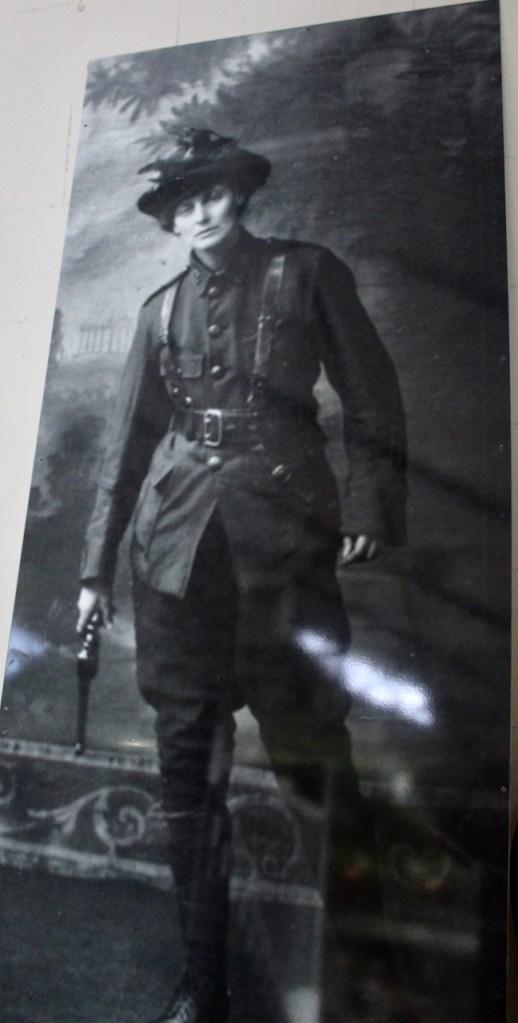

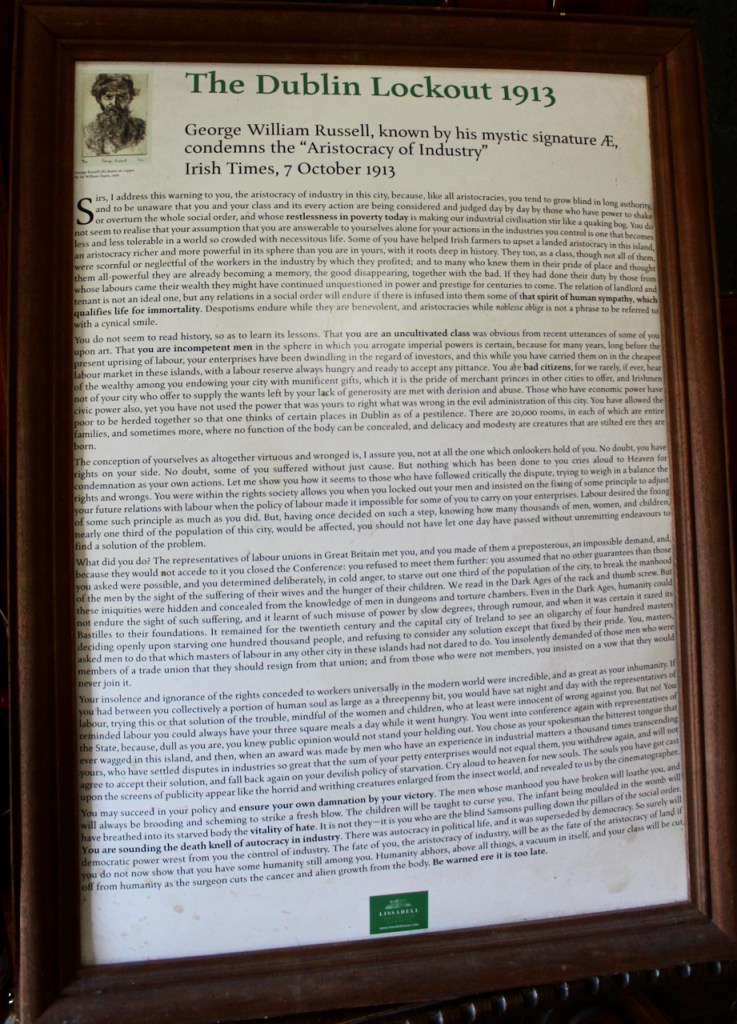

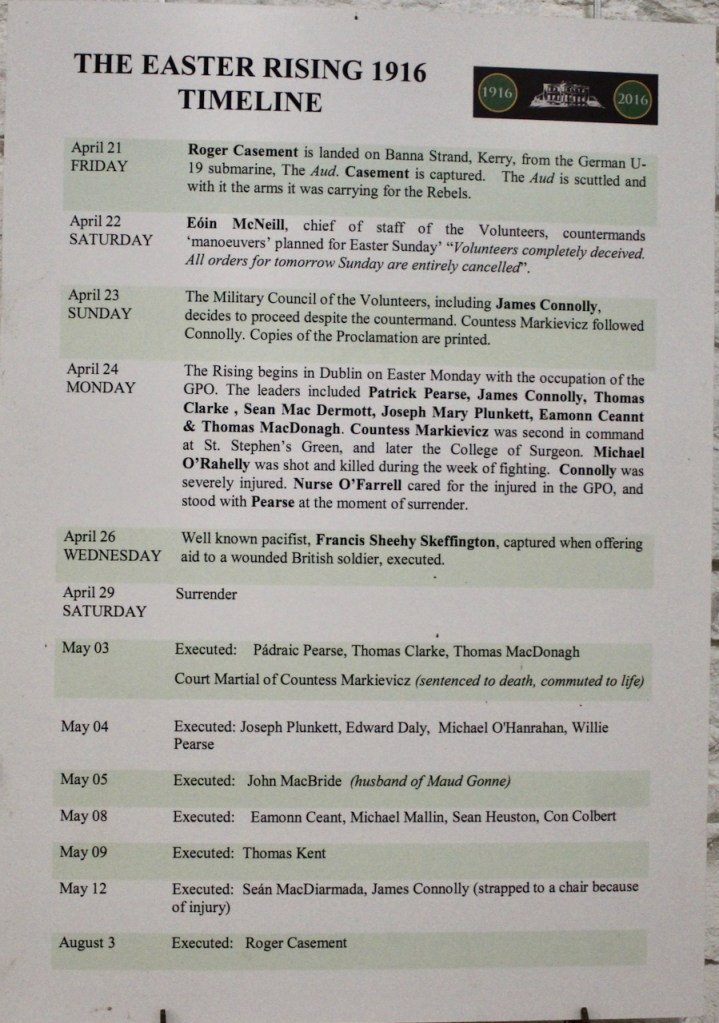

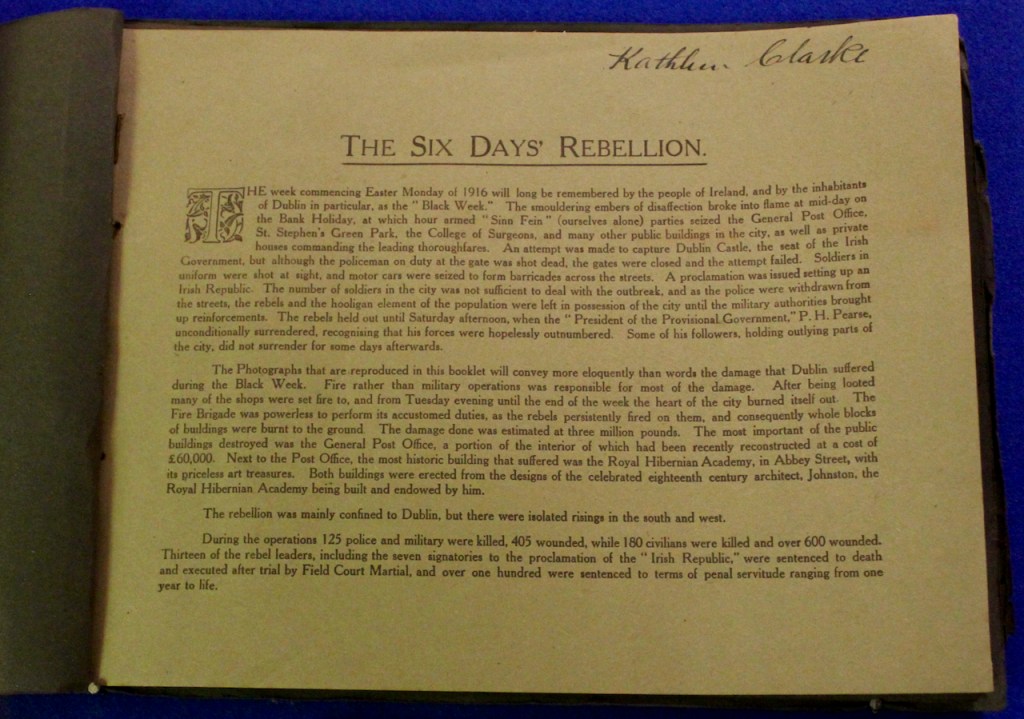

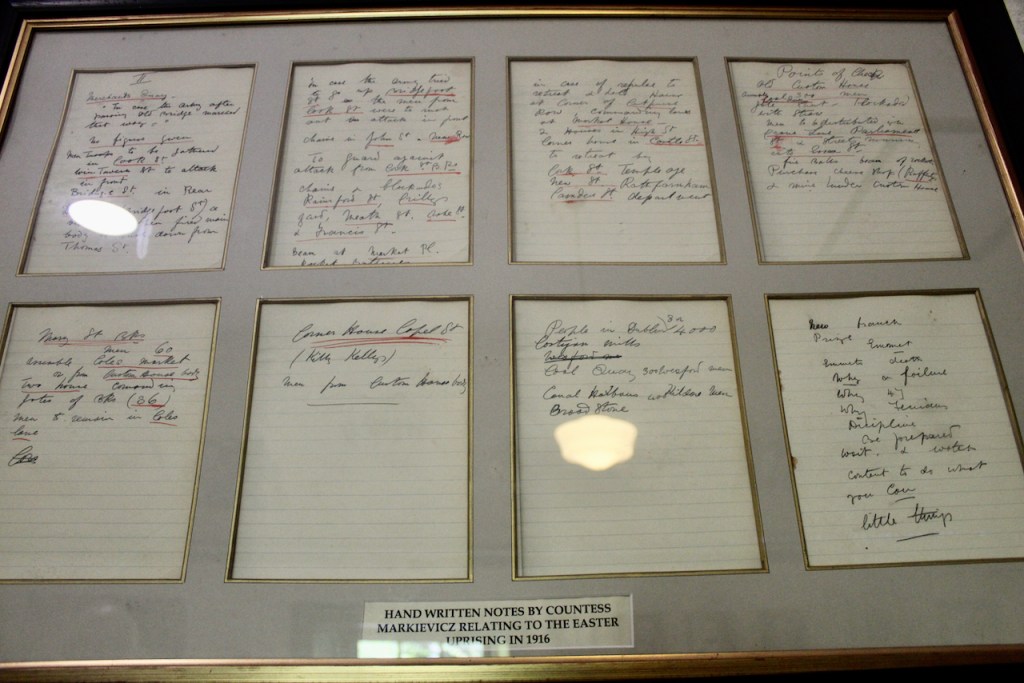

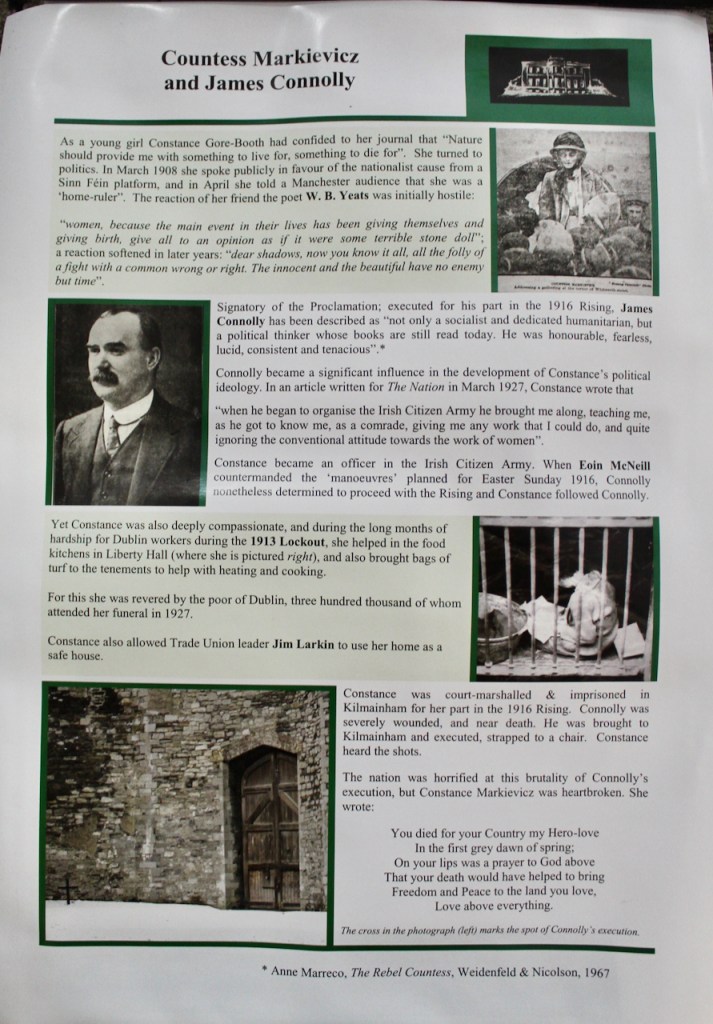

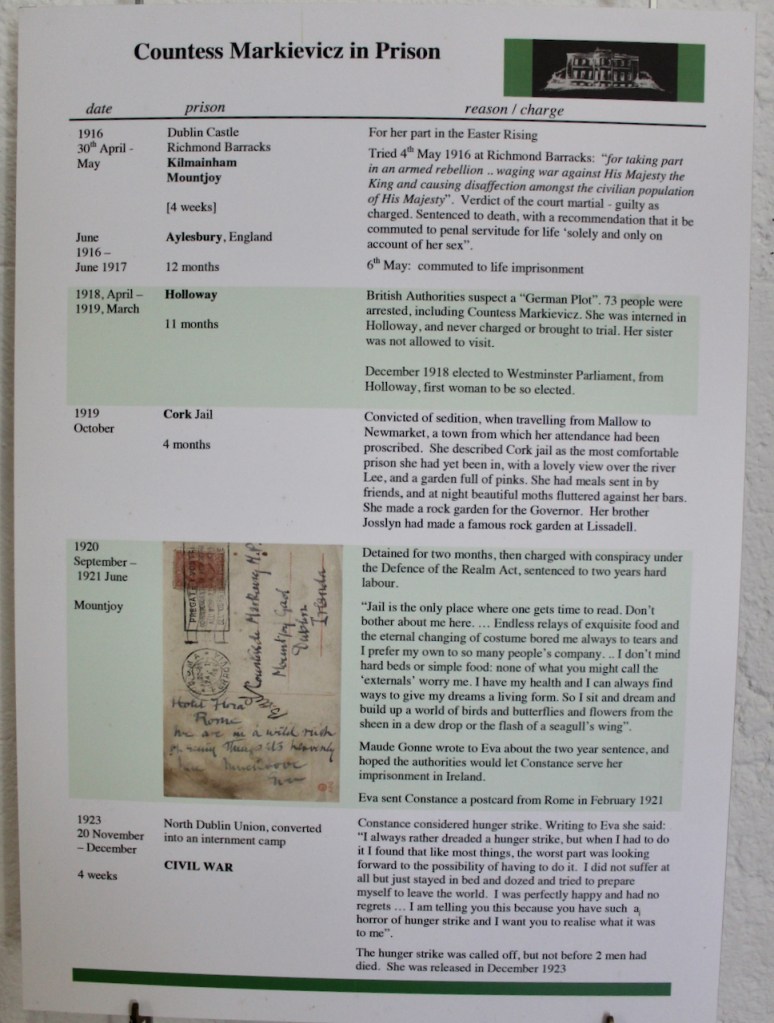

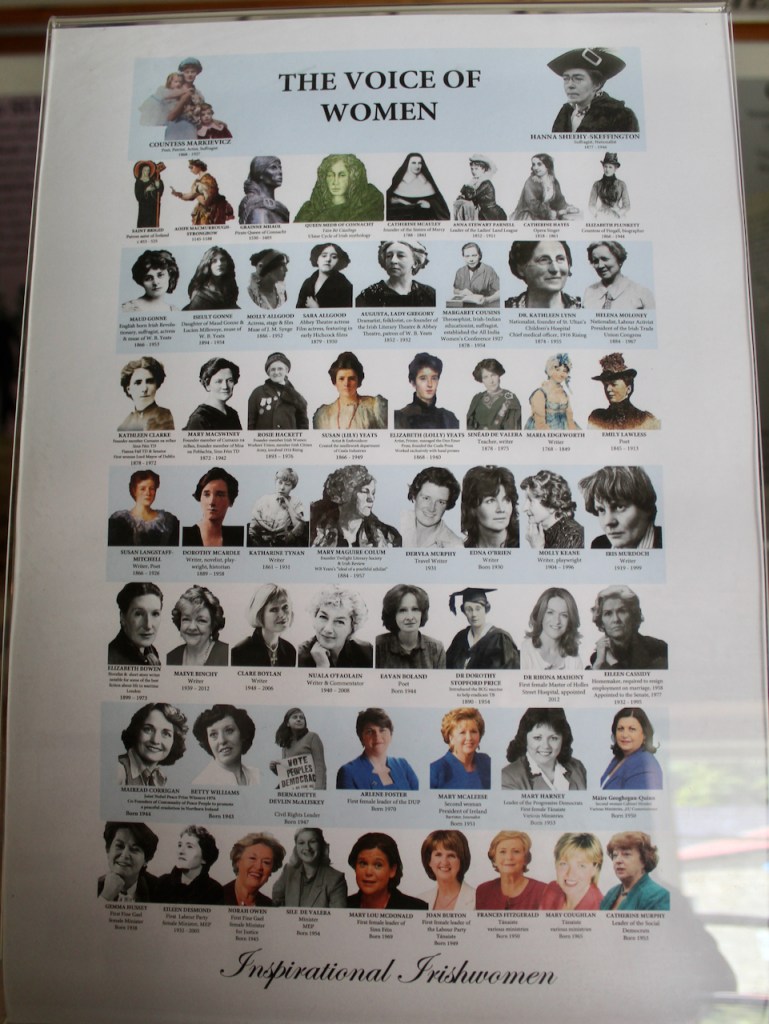

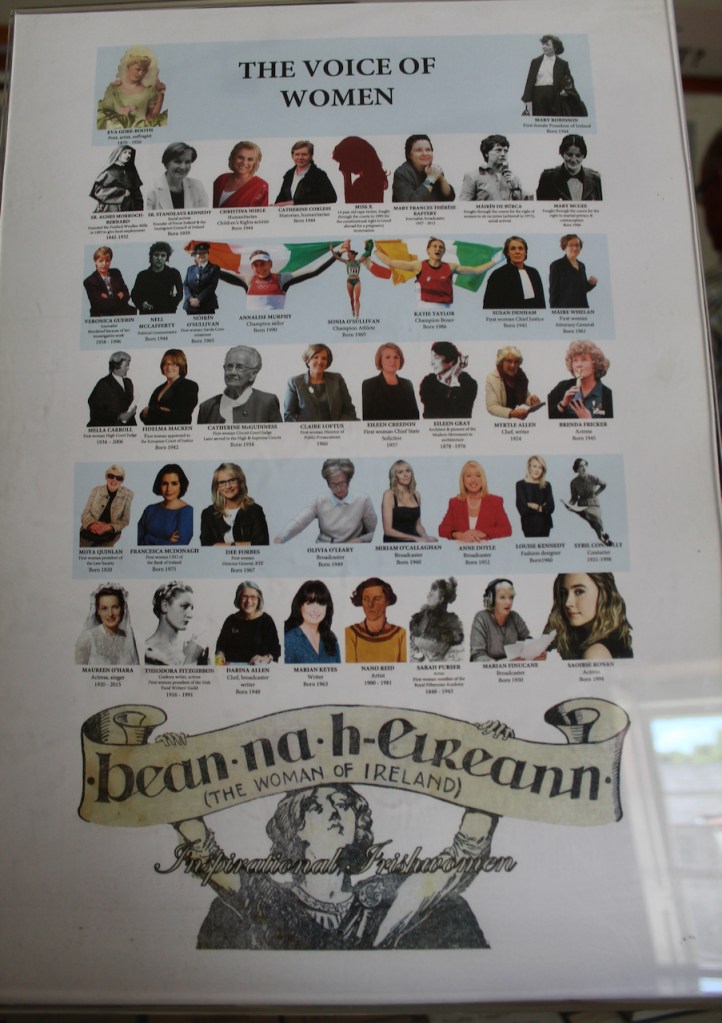

Constance had a strong social conscience, and became involved in the 1913 Lockout, where workers went on strike for better pay. She was then involved in the 1916 Rising, and was jailed for her activity. When the new state was born, she was elected to Dáil Eireann, where she served as Minister for Labour. She was also the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons at Westminster, London, but like many other Irish politicians, she declined to take her seat – members of Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland continue in this tradition and refuse to take their seats in Westminster.

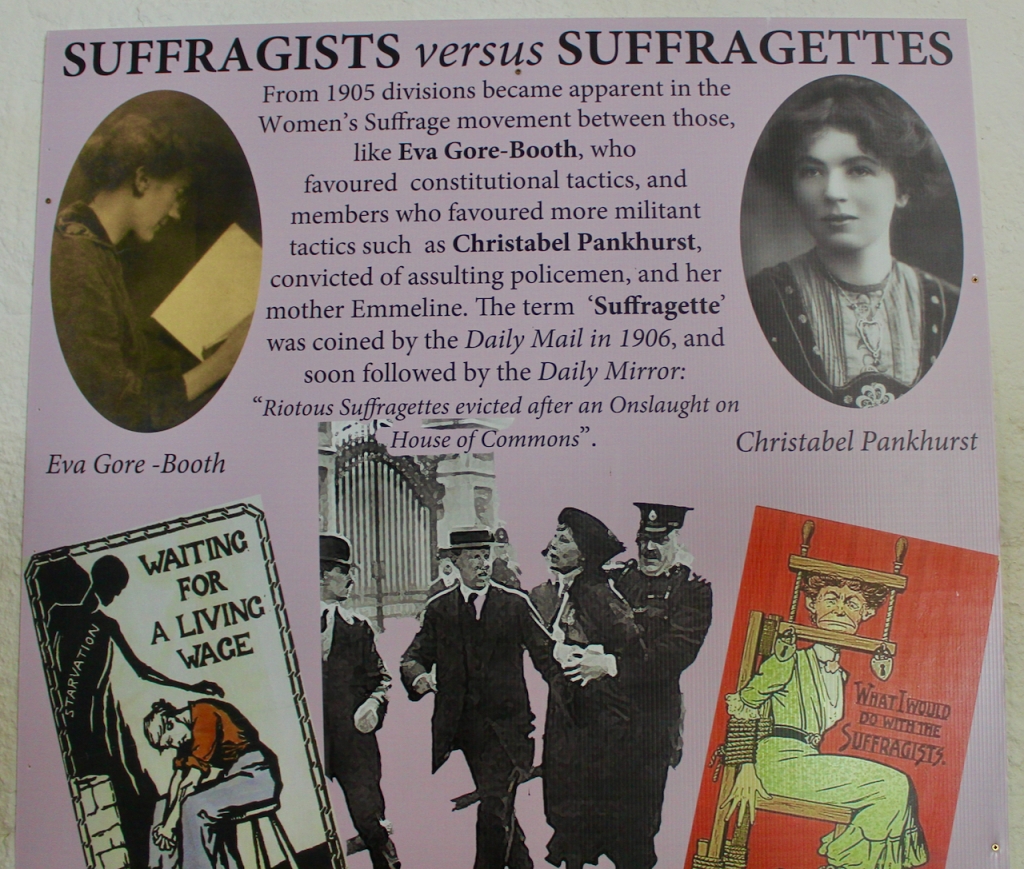

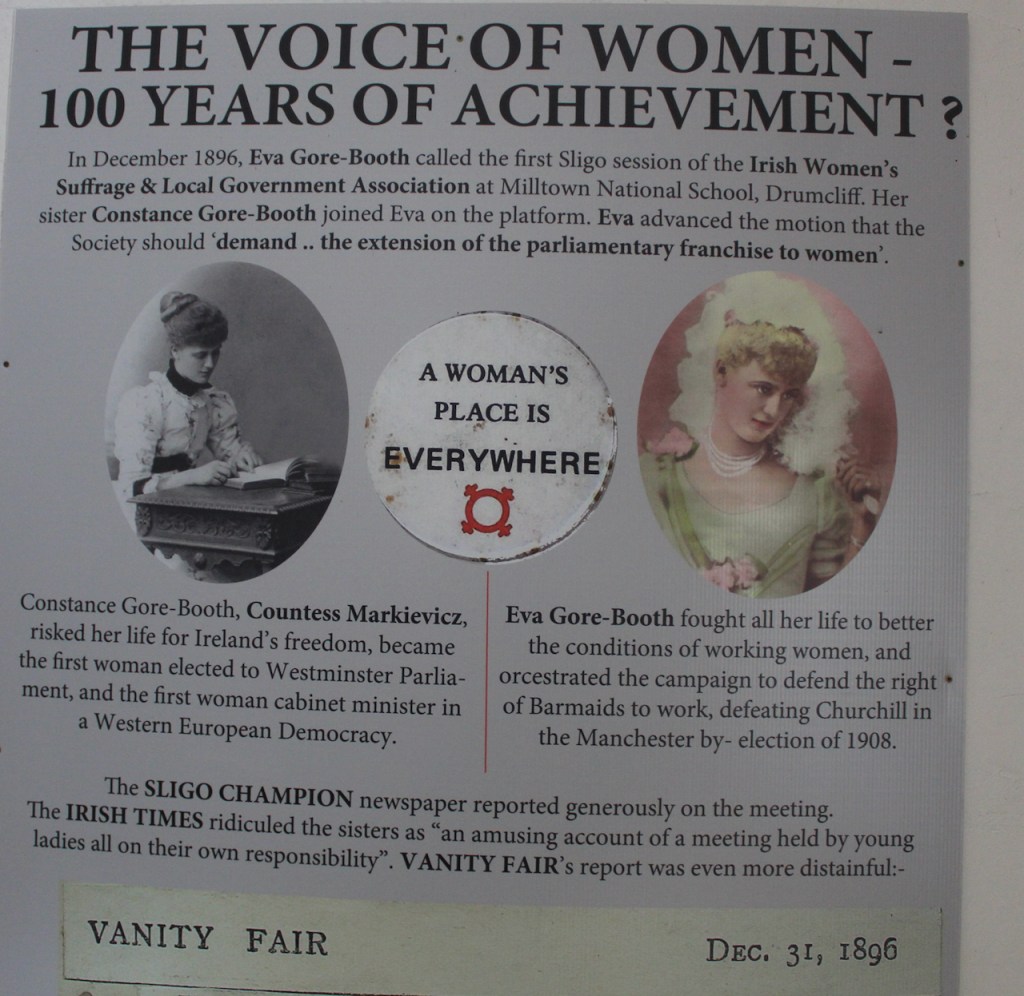

Eva was a suffragist and poet, and lived in meagre circumstances in England with her partner Esther Roper.

Eva fought for Women’s Rights and clashing with the young Winston Churchill over barmaids’ rights in 1908. She spent many years in Manchester working to alleviate the condition of working women.

Eva wrote:

The little waves of Breffny

The grand road from the mountain goes shining to the sea

And there is traffic on it and many a horse and cart,

But the little roads of Cloonagh are dearer far to me

And the little roads of Cloonagh go rambling through my heart.

A great storm from the ocean goes shouting o’er the hill,

And there is glory in it; and terror on the wind:

But the haunted air of twilight is very strange and still,

And the little winds of twilight are dearer to my mind.

The great waves of the Atlantic sweep storming on their way,

Shining green and silver with the hidden herring shoal;

But the little waves of Breffny have drenched my heart in spray,

And the little waves of Breffny go stumbling through my soul.

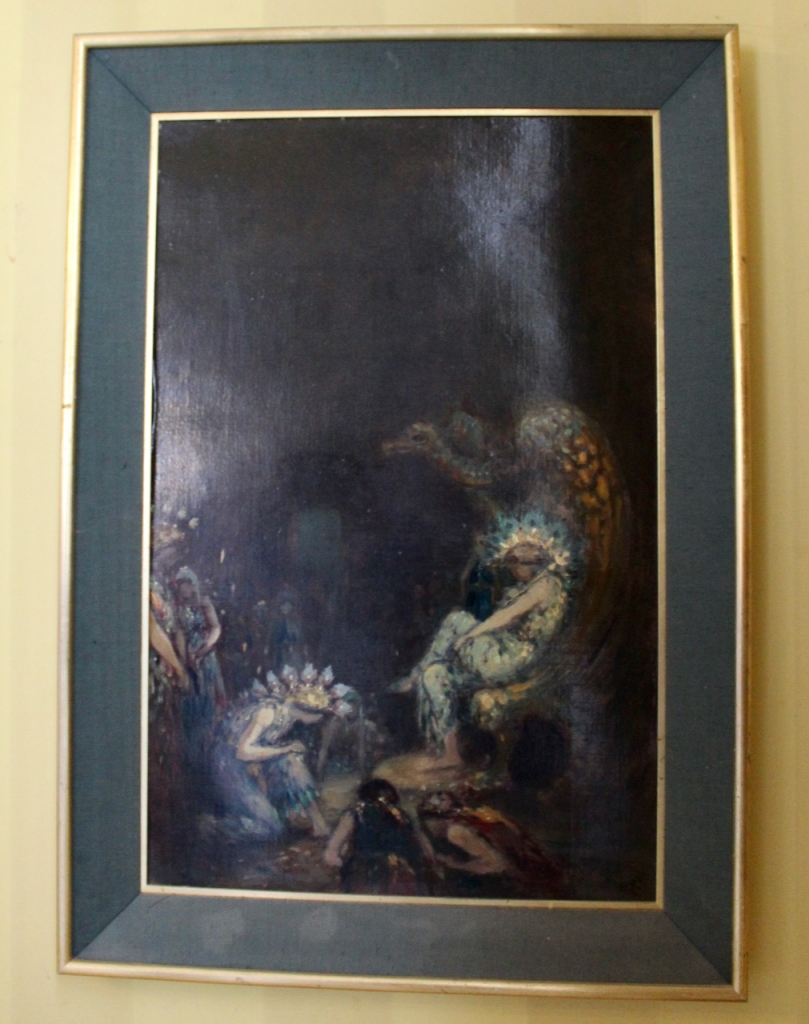

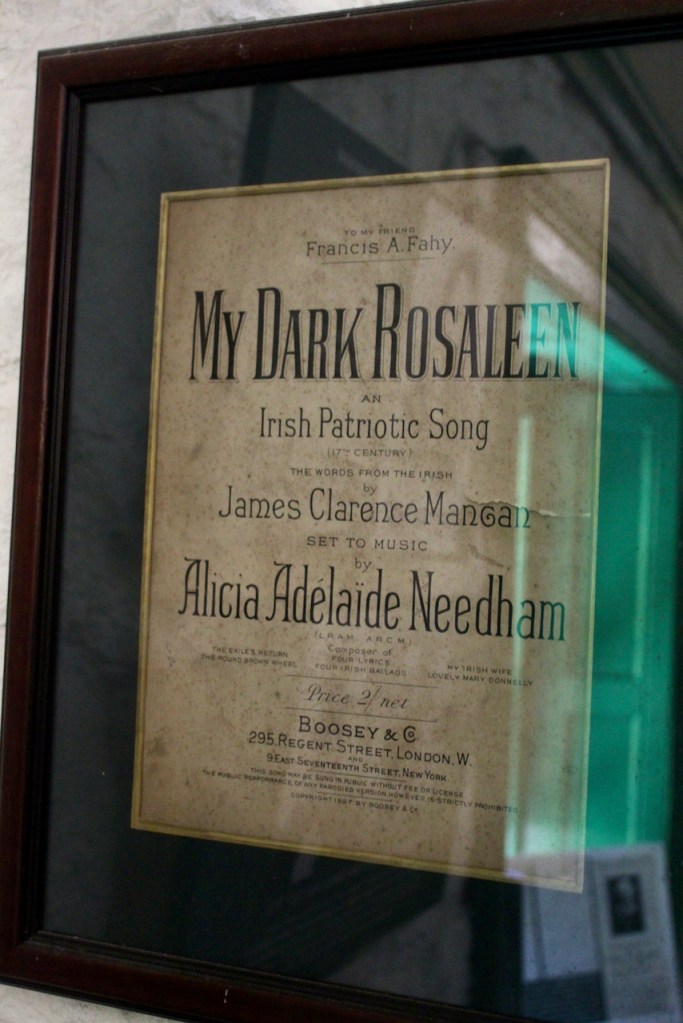

There is also a collection of paintings by a friend of W.B. Yeats, “A.E.” i.e. George William Russell, who was also part of the farming Co-operative movement and, like Yeats, a mystic.

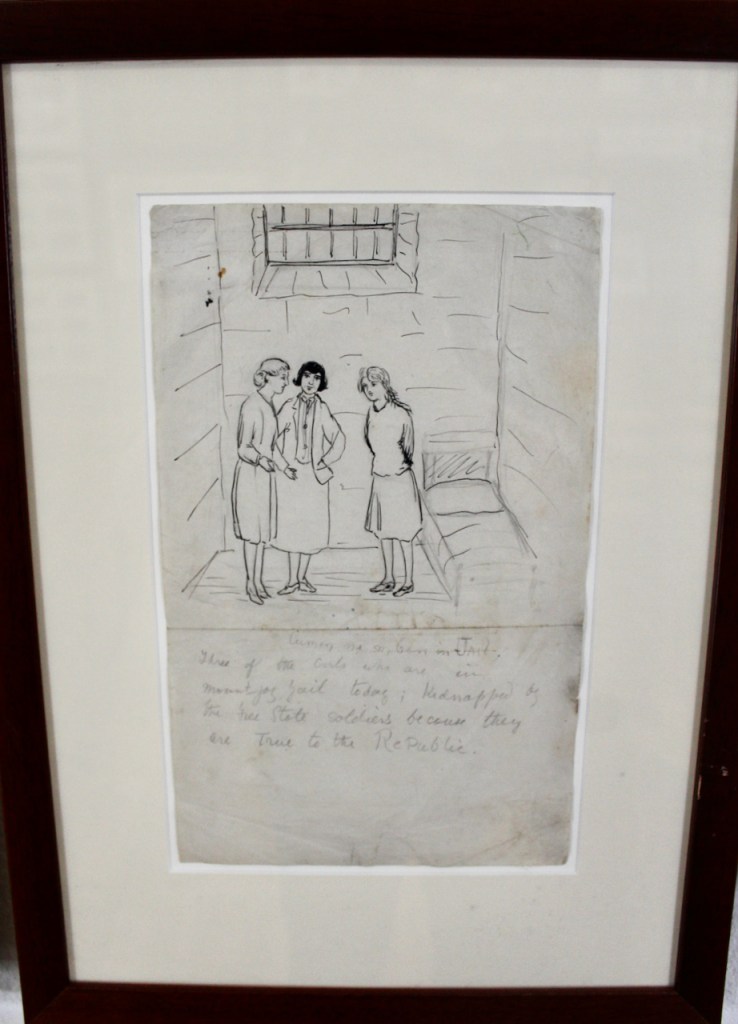

The anteroom still has an engraving that Constance made with her sister Mabel in a windowpane with a diamond in 1898. Drawings from Constance’s sketchbook are displayed also.

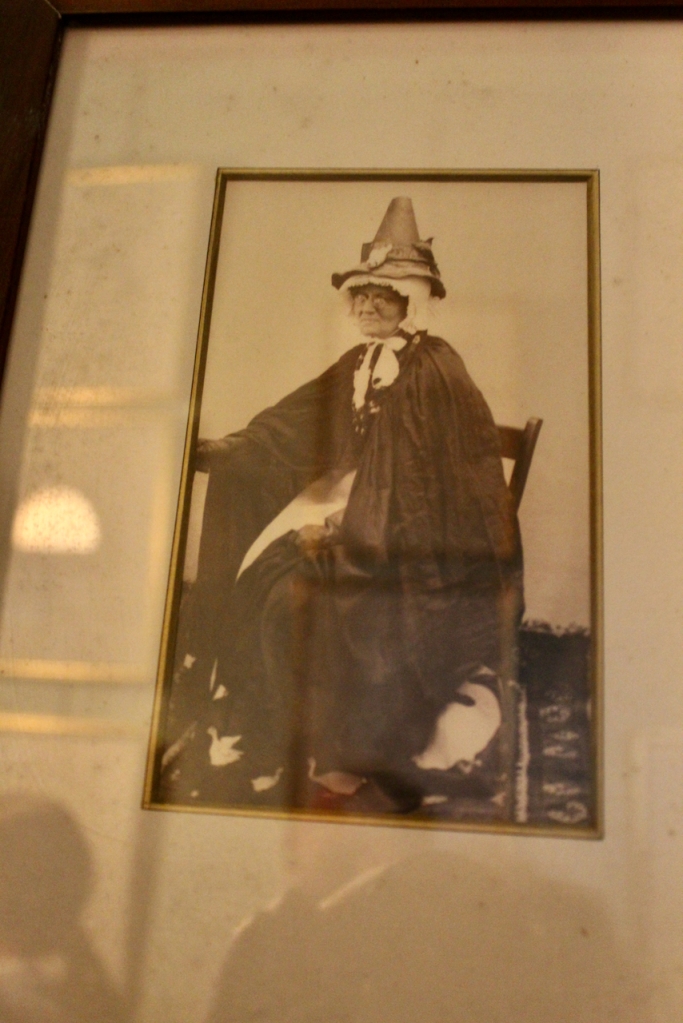

I had been particularly looking forward to seeing the dining room as I had seen pictures of it before and it has rather eccentric paintings which I love! Again, it was hard to take photographs because the room was crowded with the tour. Casimir painted portraits onto the pillars. He painted some of the servants, including Kilgallon. The bear shot by Kilgallon stands now beside his portrait.

Next we went down to the basement, which holds the old kitchen and a warren of corridors.

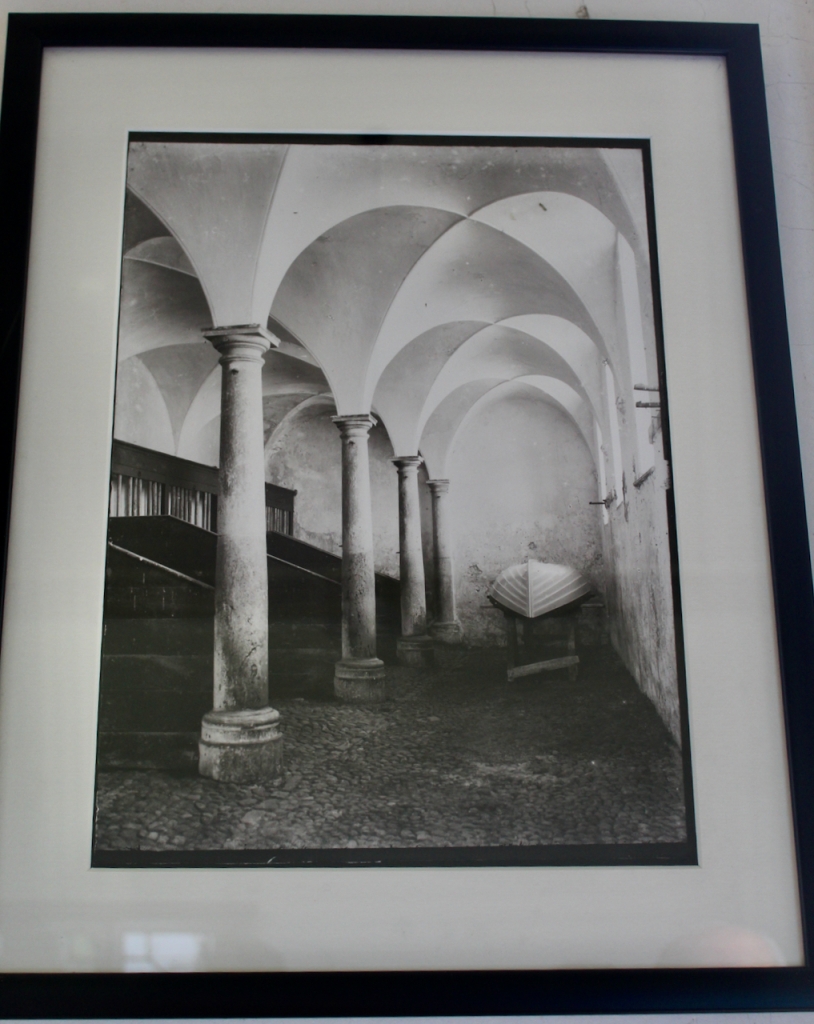

The long tunnel provides access to a sunken courtyard and the coach house and stable block, which was one of the largest in Ireland. This limestone complex of stables, tack rooms, grain stores and rooms once for staff and guests is now almost completely restored. Today it houses tea rooms, a gallery for exhibitions and lecture rooms.

In the 20th century the family fortunes took a turn for the worse. Constance and Eva died in their 50s. Constance died in 1927 and Eva in 1926.

In June 1927 Constance fell seriously ill. She was admitted to a public ward in Sir Patrick Dun’s hospital (at her own insistence). She had peritonitis, and although she had surgery, it was too late. Constance Markievicz died at 1:25 a.m. on the morning of 15th July, 1927. She was attended by her husband, Casimir. Her brother, Sir Josslyn Gore Booth, had received daily bulletins from the Matron, and immediately arranged to attend the funeral in Dublin.

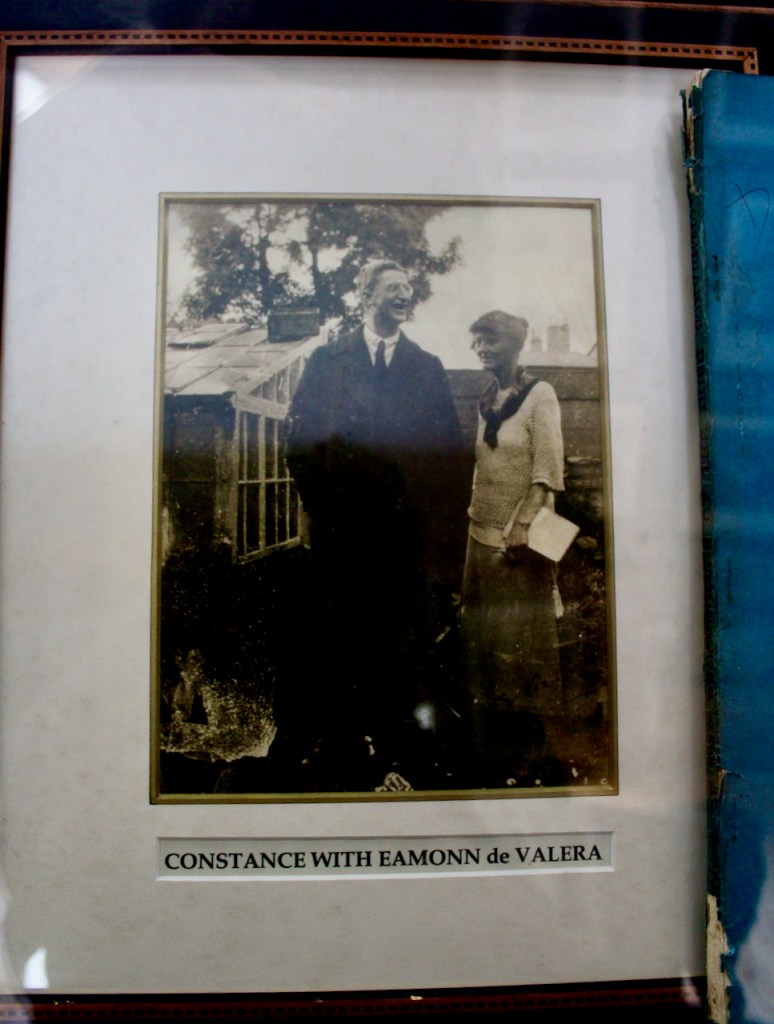

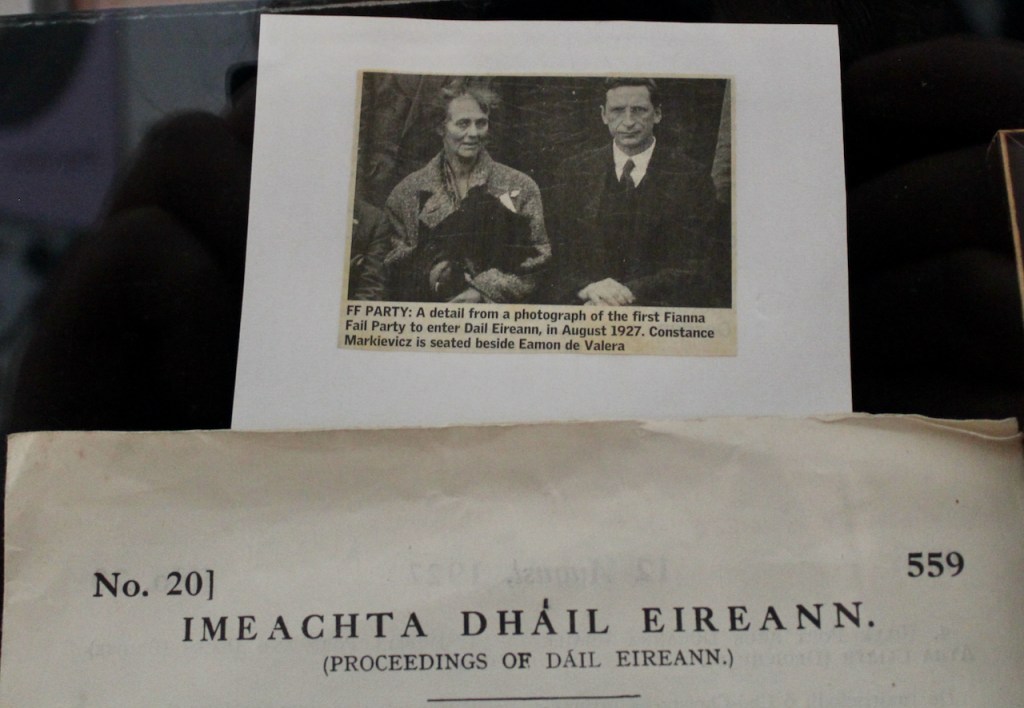

Her brother Josslyn would have preferred a private, family funeral, but this was not to be. In death Constance Markievicz was even more openly appreciated and acclaimed than in life. Three hundred thousand people attended the funeral to pay tribute to “the friend of the toiler, the lover of the poor”, the words of Eamon de Valera, who delivered the funeral oration, and with whom she had founded the Fianna Fáil Party.

Two of Josslyn’s sons, Hugh and Brian, were killed in WWII. Hugh, the younger brother, studied estate management in England to run the estate. Brian joined the Navy. The third son, Michael, suffered from mental illness that made him incapable of running the family estate. Josslyn was still alive at this stage, and his four daughters continued to live on the estate – three of them never married. When their father died in 1944, the government assumed responsibility for the administration of the estate when Sir Josslyn’s eldest son was made a ward of the court after a nervous breakdown. Gabrielle took over the responsibility of running the estate at the age of just 26. [8] There was a youngest son also, Angus Josslyn, who succeeded as 8th Baronet. When Gabrielle died, Aideen took over the estate. For decades, the family struggled to maintain the house and the gardens became neglected and overgrown.

The family migrated to live in the bow-room and a small suite of rooms behind when the family of Gore-Booth siblings were living in near poverty in the 1960s and 70s, when the remainder of the house was uninhabited.

During this time the estate went into sharp decline, resulting in the felling of much fine woodland and the compulsory sale in 1968 of 2,600 acres by the Land Commission, leaving only 400 acres around the house.

Terence Reeves-Smyth tells us in Irish Big Houses: “The Lissadell estate had fallen into decline after the death of Josslyn Gore Booth in 1944. Indeed, writing about Lissadell for the Sunday Times around forty years ago, the BBC’s Anne Robinson observed that “the garden is overgrown, the greenhouses are shattered and empty, the stables beyond repair, the roof of the main block leaks badly and the paintings show patches of mildew.” It also featured in the documentary “The Raj in the Rain.”

In 2003 Lissadell was put on the market by the 9th Baronet, Josslyn Henry Robert Gore-Booth (b. 1950), son of Angus the 8th Baronet. You can listen to his memories of Lissadell online, part of the Irish Life and Lore series. [9] It was purchased by Edward Walsh and his wife Constance Cassidy, to become home for them and their seven children.

In the Image publication Great Irish Houses we are told that Edward and his wife Constance commissioned David Clarke, an architect with Moloney O’Beirne, to prepare a conservation plan and restoration of the house began in 2004. Assistance and expert advice was received from Laurence Manogue, a consultant to Sligo County Council. [10]

The Image publications book tells us that there has been a great focus on the gardens, with regeneration of the flower and pleasure gardens. The alpine nurseries with its “revetment walls” (limestone and sandstone), terraces, and ornamental ponds had been neglected for half a century. Now the gardens are cleared and the orchards and two-acre kitchen garden have been reseeded. The plan, in many ways, is to resurrect the horticultural enterprise of Henry and Josslyn Gore Booth. Thirty-eight of an original seventy-eight daffodil narcissus cultivars developed by Sir Josslyn are now back in the ground at Lissadell.

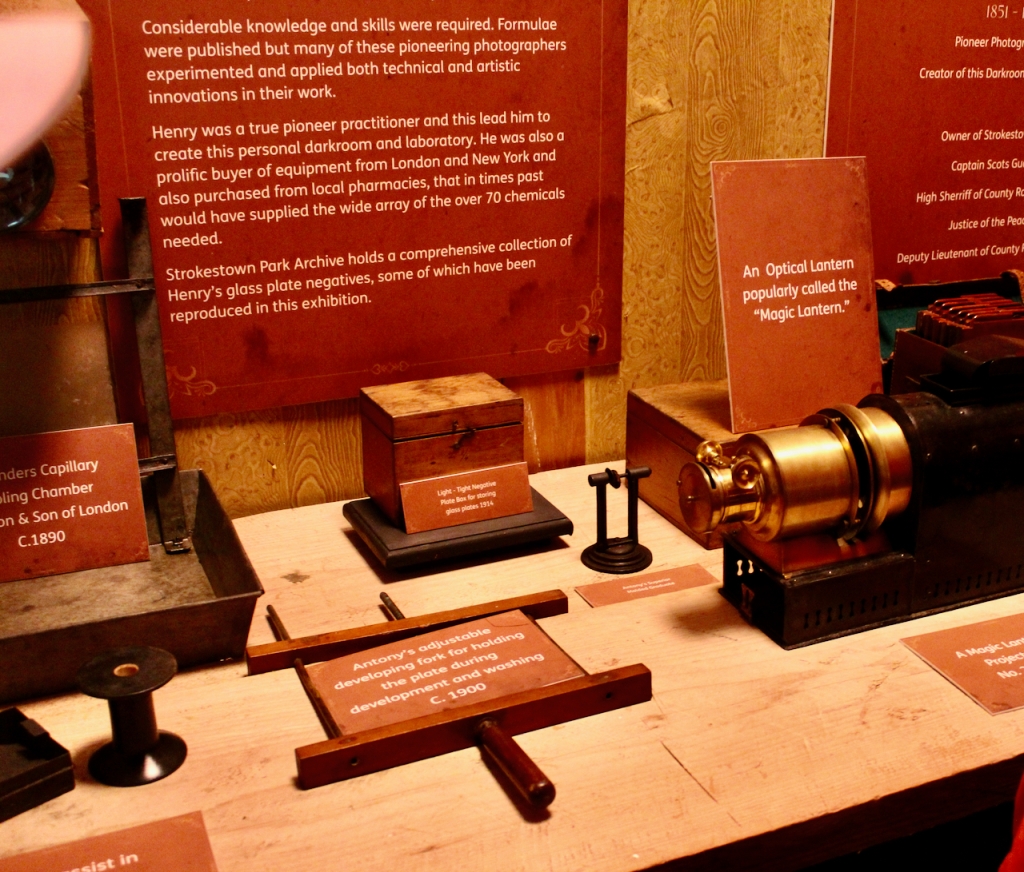

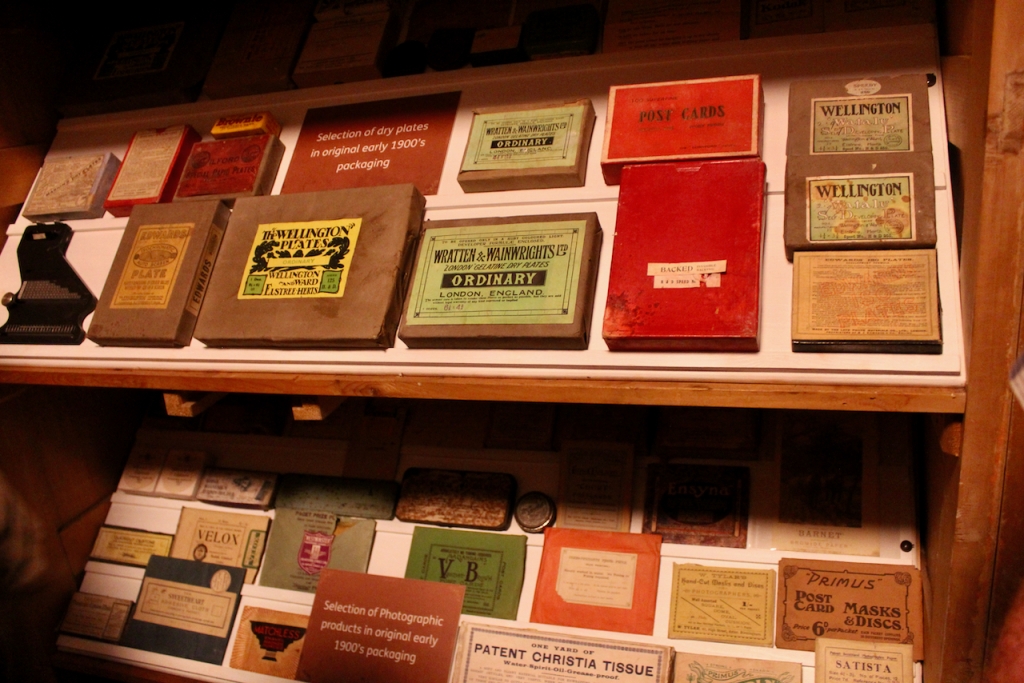

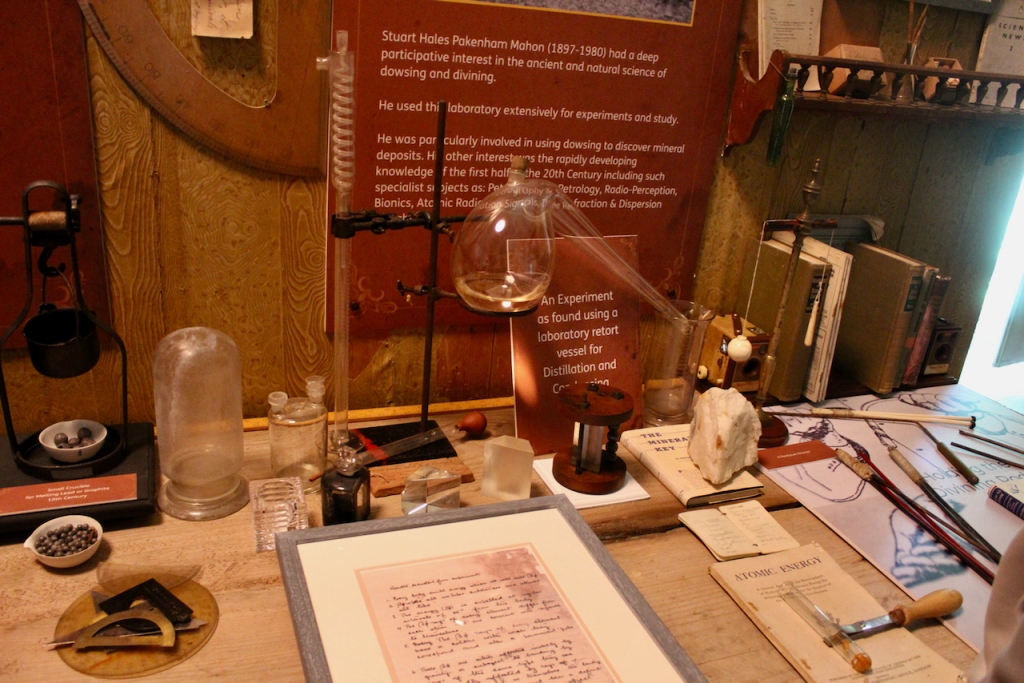

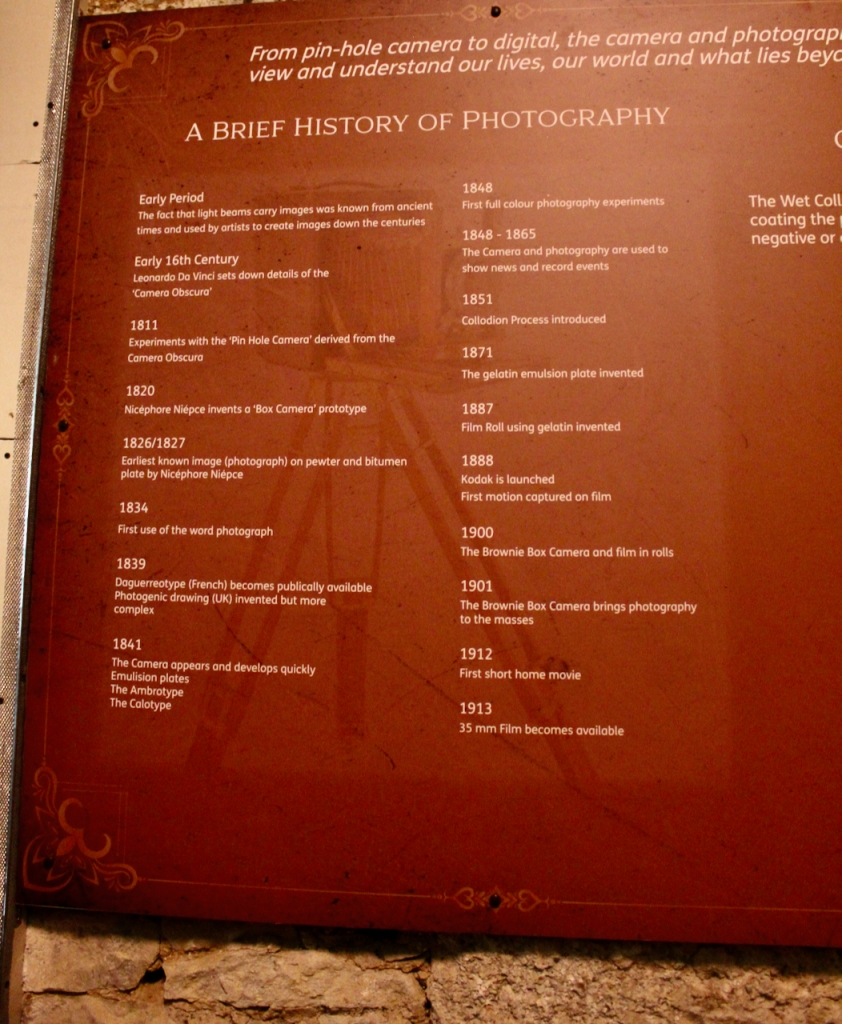

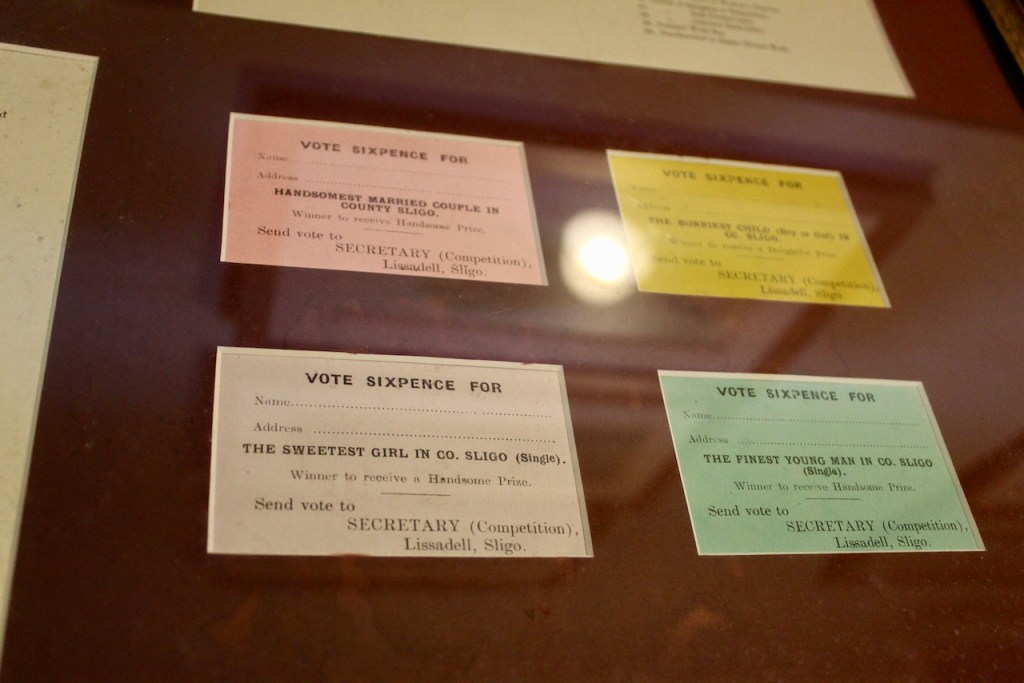

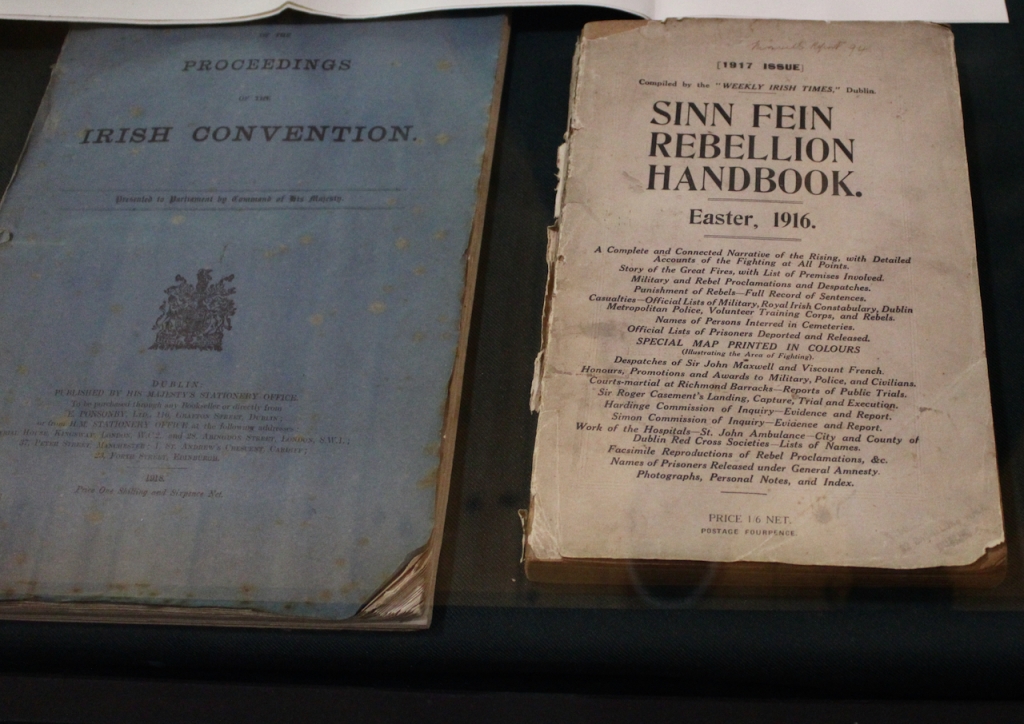

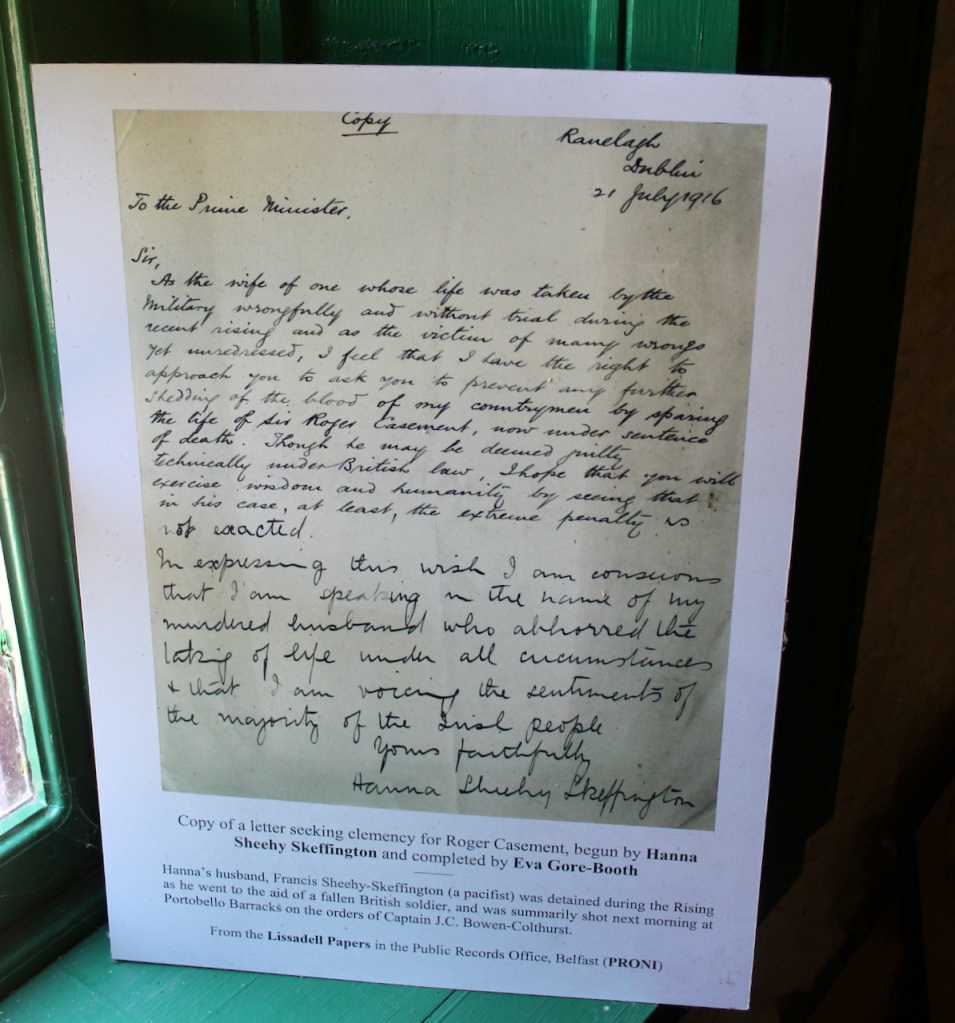

There is an extensive museum in the Cafe building, with areas dedicated to Constance Markievicz and W. B. Yeats.

[2] https://www.ardtarmoncastle.com/

[3] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/search/label/County%20Sligo%20Landowners

[4] p. 11. James, Dermot. The Gore-Booths of Lissadell. Published by Woodfield, 2004

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2021/11/22/lissadell/

[6] p. 40, James.

[7] p. 214, Great Irish Houses. Foreward by Desmond FitgGerald, Desmond Guinness. IMAGE Publications, 2008.

[8] For more about Gabrielle and her struggle to manage the estate, see https://lissadellhouse.com/countess-markievicz/gore-booth-family/gabrielle-gore-booth/

[9] https://www.irishlifeandlore.com/product/sir-josslyn-gore-booth-b-1950-part-1/

This collection includes Patrick Annesley b. 1943 speaking about Annes Grove in County Cork; Valerie Beamish-Cooper b. 1934; Bryan and Rosemarie Bellew of Barmeath Castle County Louth; Charles and Mary Cooper about Markree Castle in Sligo; Leslie Fennell about Burtown in Kildare; Maurice Fitzgerald 9th Duke of Leinster and Kilkea Castle, County Kildare; Christopher and Julian Gaisford St. Lawrence and Howth Castle; George Gossip and Ballinderry Park; Nicholas Grubb and Dromana, County Waterford, into which he married, and Castle Grace, County Tipperary, where he grew up; Caroline Hannick née Aldridge of Mount Falcon; Mark Healy-Hutchinson of Knocklofty, County Tipperary; Michael Healy-Hutchinson, Earl of Donoughmore, son of Anita Leslie of Castle Leslie; Susan Kellett of Enniscoe; Nicholas and Rosemary MacGillycuddy of Flesk Castle, County Kerry and Aghadoe Heights; Harry McCalmont of Mount Juliet, County Kilkenny; Nicholas Nicolson of Balrath Estate; Durcan O’Hara of Annaghmore, County Sligo; Sandy Perceval of Temple House, County Sligo; Myles Ponsonby, Earl of Bessborough; Benjamin and Jessica Bunbury of Lisnavagh, County Carlow; Philip Scott of Barnfield House, Gortaskibbole, Co. Mayo; George Stacpoole of Edenvale House, Co. Clare; Christopher Taylour, Marquess of Headfort; Richard Wentges of Lisnabin Castle and Philip Wingfield of Salterbridge, County Waterford.

[10] p. 218, Image publications.

[11] Lissadell features in Irish Castles and Historic Houses. ed. by Brendan O’Neill, intro. by James Stevens Curl. Caxton Editions, London, 2002.

Featured in Mark Bence Jones, Life in an Irish Country House. Constable, London. 1996.

Featured in Irish Country Houses, Portraits and Painters. David Hicks. The Collins Press, Cork, 2014.

Featured in Irish Big Houses by Terence Reeves-Smyth

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com