On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

Places to visit in County Longford:

1. Castlecor House, County Longford, open by previous arrangement.

2. Maria Edgeworth Visitor Centre, Longford, County Longford.

3. Moorhill House, Castlenugent, Lisryan, Co. Longford – section 482

Places to stay, County Longford:

1. Castlecor House, County Longford – accommodation

2. Newcastle House Hotel, Ballymahon, County Longford

3. Viewmount House, Longford – accommodation and weddings

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Places to visit in County Longford:

1. Castlecor House, County Longford, open by previous arrangement:

I’ve been looking forward to staying in Castlecor house, after seeing a photograph of its incredible octagonal room.

The website tells us:

“The construction of this magnificent residence, as it stands today, spanned 300 years, originally built in the mid 1700’s as a Hunting Lodge with additions in the 19th & 20th century.“

The website continues: “It was built by the Very Revd. Cutts Harman (1706 – 1784), son of the important Harman family of nearby Newcastle House [which offers accommodation]. He was Dean of Waterford cathedral from 1759 and was married to Bridget Gore (1723-1762) from Tashinny [Tennalick, now a ruin, which passed from the Sankey family to the Gore family by the marriage of Bridget’s mother Bridget Sankey to George Gore, son of Sir Arthur Gore, 1st Baronet of Newtown Gore, County Mayo] in c. 1740.“

The National Inventory of Architectural Heritage (www.buildingsofIreland.ie) gives the building an unusually long appraisal which explains the unusual building:

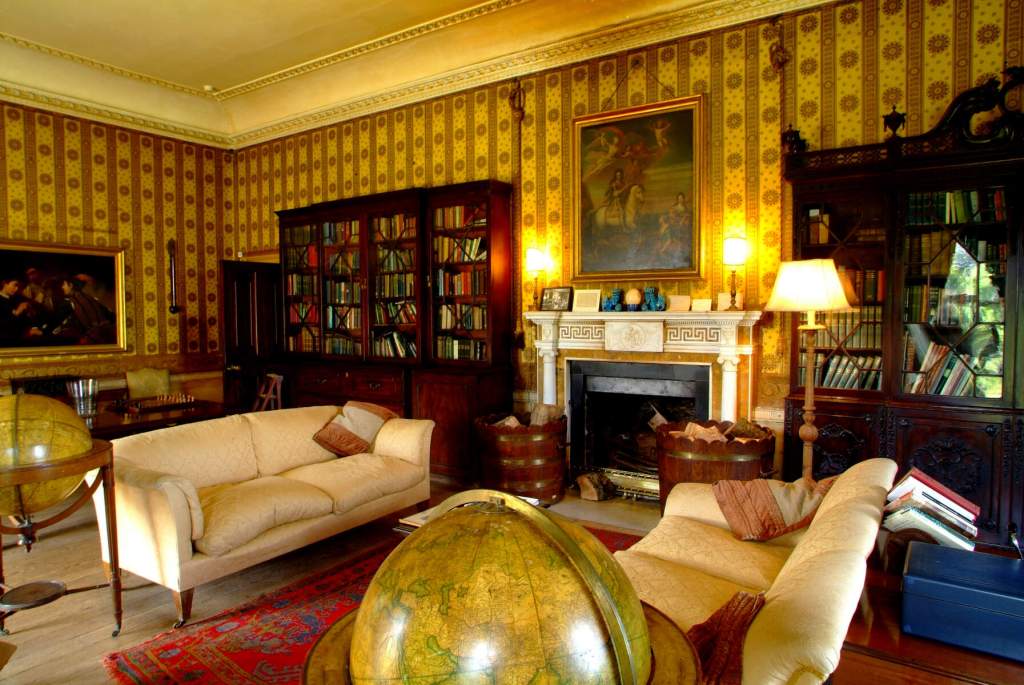

“It was originally built as a symmetrical two-storey block on octagonal-plan with short (single-room) projecting wings to four sides (in cross pattern on alternating sides), and with tall round-headed window openings between to the remaining four walls. The single wide room to the octagon at first floor level has an extraordinary central chimneypiece (on square-plan) with marble fireplaces to its four faces; which are framed by Corinthian columns that support richly-detailed marble entablatures over. The marble fireplaces themselves are delicately detailed with egg-and-dart mouldings and are probably original. This room must rank as one of the most unusual and interesting rooms built anywhere in Ireland during the eighteenth-century.“

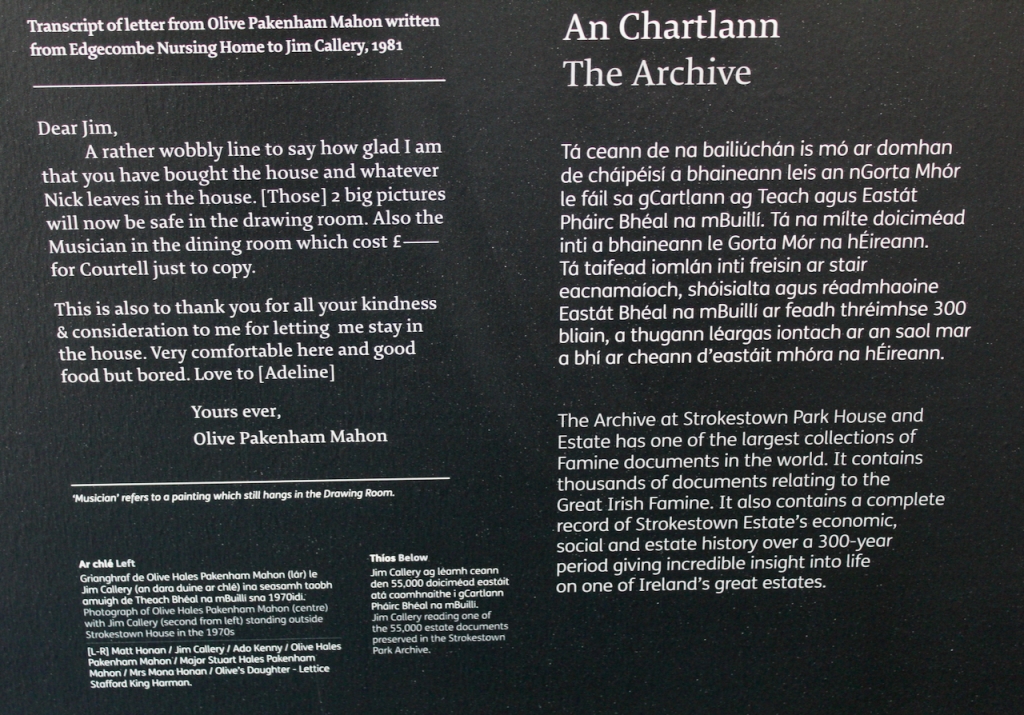

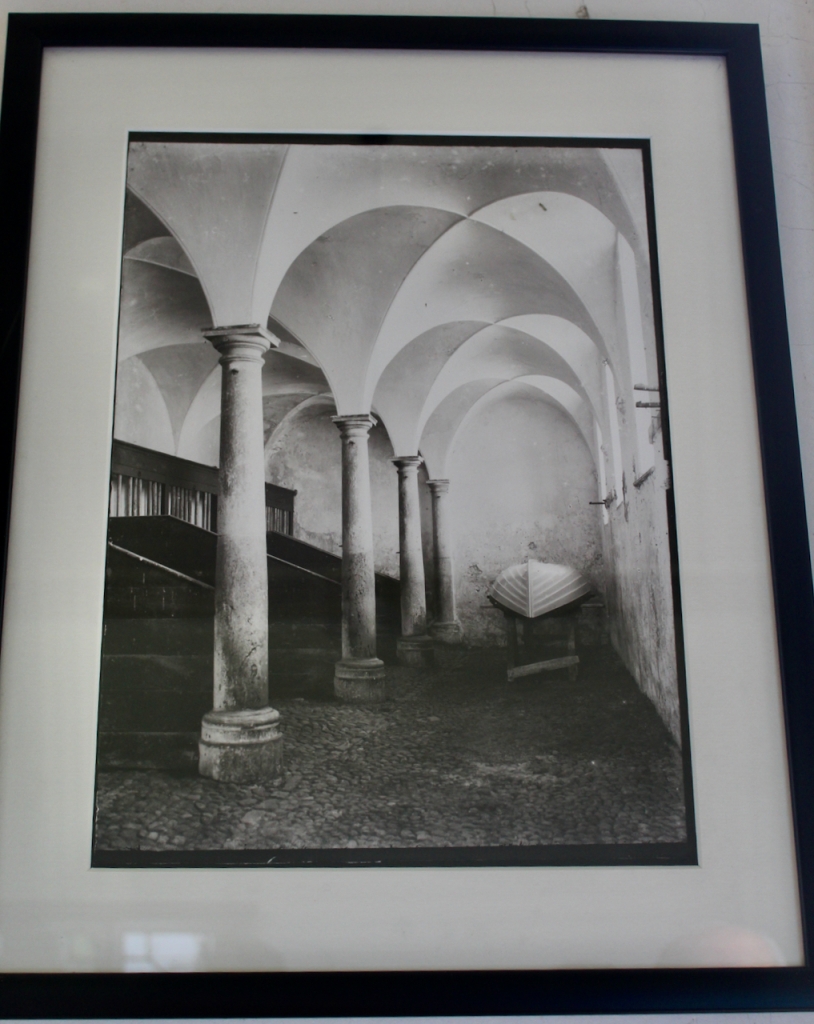

The National Inventory continues: “The walls of the octagonal room are decorated with Neo-Egyptian artwork, which may have been inspired by illustrations in Owen Jones’ book ‘Decoration’, published in 1856. The inspiration for this distinctive octagonal block is not known. Some sources suggest an Italian inspiration, such as the pattern books of the noted architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475 – 1554) [Mark Bence-Jones suggests this [2]], or that it was based on the designs of the much larger hunting lodge (Palazzina di caccia of Stupinigi) that was built for the Duke of Savoy, near Turin, between 1729 and c. 1731 (The later seems a highly fanciful idea but there are some similarities in plan, albeit on a much larger scale at Stupinigi); while Craig (1977, 15) suggests that the ‘inspiration is clearly the hunting lodge at Clemenswerth in Lower Saxony, Germany’, which was constructed between 1737 – 1747 to designs by Johann Conrad Schlaun for Prince Clemens August, a structure that Castlecor resembles in terms of scale and plan. However, it may be that the plan of this building was inspired by William Halfpenny (died 1755), an English Palladian architect who created a number of unexecuted designs for Waterford Church of Ireland cathedral and for an associated bishop’s palace from c. 1739. Interestingly, a number of these unexecuted plans for the bishop’s palace included a central octagonal block with projecting wings, while a number of the church plans included an unusual separate baptismal building attached to the nave, which is also on an octagonal-plan. The Very Revd. Cutts Harman may well have been aware of Halfpenny’s unexecuted designs, being Dean of the cathedral from 1759 and was probably associated with the diocese from an earlier date, and perhaps he used these as his inspiration for the designs of Castlecor. The central four-sided chimneypiece is reminiscent of the centerpiece of the Rotunda of Ranelagh Gardens, London, (built to designs by William Jones 1741 – 2; demolished c. 1803) albeit on a much reduced scale at Castlecor. The plan of Castlecor is also similar to a number of buildings (some not executed) in Scotland, including Hamilton Parish Church (built c. 1733 to designs by William Adam (1698 – 1748) and the designs for a small Neoclassical villa prepared by James Adam (1732 – 92), c. 1765, for Sir Thomas Kennedy. The exact construction date of Castlecor is not known, however the traditional building date is usual given as c. 1765. The architectural detailing to the interior of the original block, and perhaps the personal life of Very Revd. Cutts Harman (married in 1751 to a daughter of Lord Annaly of Tennalick 13402348; his duties at Waterford cathedral from 1759; Cutts Harmon leased out a number of plots of land in Longford from c. 1768) would suggest an earlier date of, perhaps, the 1740s. The architect is also unknown although it is possible that Harman designed the house himself (perhaps inspired by a pattern book or by Halfpenny’s unexecuted designs); while Craig (1977) suggest that the architect may have been Davis Ducart (Daviso de Arcort; died 1780/1), an Italian or French architect and engineer who worked extensively in Ireland (particularly the southern half of the island) during the 1760s and 1770s.” We saw Ducart’s work at Kilshannig in County Cork, another section 482 property, see my entry [3].

The website tells us:”The Rev. Cutts Harman who had Castlecor built died without issue, it was inherited by his niece’s son [or was it his sister Anne’s son? If so, it was her son Lawrence Harman Parsons (1749-1807); she married Laurence Parsons, 3rd Baronet of Birr Castle. Her son added Harman to his surname when he inherited Castlecor from his uncle], Laurence Harman- Harman, later Lord Oxmantown, and finally Earl of Rosse. Peyton Johnston, the Earl’s nephew, rented the house during this time. Captain Thomas Hussey, Royal Marines; purchased Castlecor in c.I820. There is very little documentary evidence relative to Captain Hussey’s occupancy. He resided there from 1832/3 to 1856 and was High Sheriff of Longford.“

Mark Bence-Jones adds: “To make the house more habitable, a conventional two storey front was built onto it early in C19, either by Peyton Johnston, who rented the house after it had been inherited by the Earl of Rosse, or by Thomas Hussey, the subsequent tenant who bought the property ante 1825. This front joins two of the wings so that its ends and theirs form obtuse angles. In the space between it and the octagon is a top-lit stair. Early in the present century, a wider front of two storeys and three bays in C18 manner, with a tripartite pedimented doorway, was built onto the front of the early C19 front. Castlecor subsequently passed to a branch of the Bonds, and was eventually inherited by Mrs C. J. Clerk (nee Bond).”

The National Inventory continues to tell us the history of the house: “The building was extended c. 1850 (the house appears on its original plan on the Ordnance Survey first edition six-inch map 1838) by the construction of a two-storey block to the northeast corner of the house, between two of the wings of the original structure. The earlier wing to the west may have been extended at this time also. The lion’s head motifs to the rainwater goods throughout the building (built around and before c. 1850) are very similar to those found at the gate lodge serving Castlecor to the northwest, built c. 1855, suggesting that the house was altered at this time, possibly as part of wider program of works at the estate.”

The National Inventory continues: “The projection to the south wing having the box bay window also looks of mid-to-late nineteenth century date and may also have been added at this time. The Castlecor estate was bought by the Hussey family during the late-eighteenth century following the death of Cutts Harman, and the first series of works may have been carried out when Capt. Thomas Hussey (1777 – 1866), High Sheriff of Longford from 1840 – 44, was in residence. However, the Castlecor estate was offered for sale by Commissioners of Incumbered Estates in 1855 when it was bought by a branch of the Bond family and, perhaps, the house was extended just after this date by the new owners. The Bonds were an important landed family in Longford at the time, and owned a number of estates to the centre of the county, to the north of Castlecor, and a branch also lived at adjacent Moygh/Moigh House (13402606) [still standing and in private hands] during the second half of the nineteenth century. Thomas Bond (1786 – 1869) [of Edgeworthstown] was probably the first Bond in residence at Castlecor. A John Bond, later of Castlecor, was High Sheriff of Longford in 1856. The last Bond owner/resident was probably a Mrs Clerk (nee Bond) [Emily Constance Smyth Bond] who was in residence in 1920. She married a Charles James Clerk (J.P. and High Sheriff of Longford in 1906) in 1901/2, and he was responsible for the three-bay two-storey block that now forms the main entrance, built c. 1913. This block was built to designs by A. G. C. Millar, an architect based on Kildare Street, Dublin. This block is built in a style that is reminiscent of a mid-eighteenth century house, having a central pedimented tripartite doorcase and a rigid symmetry to the front elevation. The house became a convent (Ladies of Mary) sometime after 1925 until c. 1980, and was later in use as a nursing home until c. 2007. This building, particularly the original block, is one of the more eccentric and interesting elements of the built heritage of Longford, and forms the centrepiece of a group of related structures.” [1]

The website tells us that the four wings adjoining the original octagonal hunting lodge align with the four cardinal compass points.

In 2009, the current owners Loretta Grogan and Brian Ginty set about purchasing the house, with the aspiration to restore Castlecor House, its grounds, native woodland and walled garden with pond and orchard to its former glory, opening it to the public by appointment and also welcoming guests.

2. Maria Edgeworth Visitor Centre, Longford, County Longford.

https://www.discoverireland.ie/longford/the-maria-edgeworth-visitor-centre

“The Maria Edgeworth Centre, in County Longford, is located in one of Ireland’s oldest school buildings that opened in 1841. Using a combination of audio, imagery and interactive displays, the centre tells the story of the Edgeworth family and the origins of the National School system. You will also learn about the role the family played in the educational, scientific, political and cultural life in Ireland. Maria Edgeworth was a notable pioneer of literature and education, a feminist and a social commentator of her time. Audios and displays are available in seven languages.”

3. Moorhill House, Castlenugent, Lisryan, Co. Longford – section 482

Open dates in 2026: Aug 1-31, Sept 1-29, 9.30am-1.30pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student/child €8

The National Inventory describes it:

“Detached three-bay two-storey over basement house on L-shaped plan, built c. 1815, having two-storey-storey return to rear (northwest) with pitched slate roof. Two-storey extension attached to the northwest end of rear return. Recently renovated. Possibly incorporating fabric of earlier building/structure. …This appealing and well-proportioned middle-sized house, of early nineteenth-century appearance, retains its early form, character and fabric. Its form is typical of houses of its type and date in rural Ireland, with a three-bay two-storey main elevation, hipped natural slate roof with a pair of centralised chimneystacks, and central round-headed door opening with fanlight. The influence of classicism can be seen in the tall ground floor window openings and the rigid symmetry to the front facade. The simple doorcase with the delicate petal fanlight over provides a central focus and enlivens the plain front elevation. The return to the rear has unusually thick walls and a relative dearth of openings, possibly indicating that it contains earlier fabric. This house forms an interesting group with the entrance gates to the southeast, the outbuildings (13401509) and walled garden to the rear, and the highly ornate railings to the southwest side featuring a sinuous vine leaf motif. The quality of these railings is such that their appearance is equally fine from both sides, the vine leaves being cast in three dimensions. They are notable examples of their type and date, and add substantial to the setting of this fine composition, which is an important element of the built heritage of the local area. Moorhill was the home of a R. (Robert or Richard) Blackall, Esq. in 1837 (Lewis). The Blackalls were an important family in the locality and built nearby Coolamber Manor c. 1837 [built for Major Samuel Wesley Blackhall (1809 – 1871)…to designs by the eminent architect John Hargrave (c. 1788 – 1833). Hargrave worked extensively in County Longford during the 1820s and was responsible for the designs for the governor’s house at Longford Town Jail in 1824; works at Ardagh House in 1826; the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Church of Ireland church at Newtown-Forbes; the remodelling of Castle Forbes, nearby Farragh/Farraghroe House (demolished); Doory Hall now ruinous; St. Paul’s Church of Ireland church, Ballinalee; and possibly for the designs of St. Catherine’s Church of Ireland church at nearby Killoe. …and [Coolamber Manor] may have replaced an earlier house associated with the Blackall family at Coolamber (a Robert Blackall (1764 – 1855), father of the above, lived in Longford in the late-eighteenth century)].

Moorhill House “was possibly the home of Robert Blackall, the father of Samuel Wensley, who was responsible for the construction of Coolamber Manor and later served as M.P. (1847 – 51) for the county before serving as Governor of Queensland, Australia from 1868 until his death in 1871. Moorhill may have been the residence of a Francis Taylor in 1894 (Slater’s Directory).”

Places to stay, County Longford:

1. Castlecor House, County Longford – see above

2. Newcastle House Hotel, Ballymahon, County Longford

https://www.newcastlehousehotel.ie

Newcastle House is a 300-year-old manor house, set on the banks of the River Inny near Ballymahon, in Co. Longford.

The website tells us; “Standing on 44 acres of mature parkland and surrounded by 900 acres of forest, Newcastle House is only one and half hour’s drive from Dublin, making it an excellent base to see, explore and enjoy the natural wonders of Ireland. So whether you are looking for a peaceful place to stay (to get away from it all) or perhaps need a location to hold an event, or that most important wedding, give us a call.”

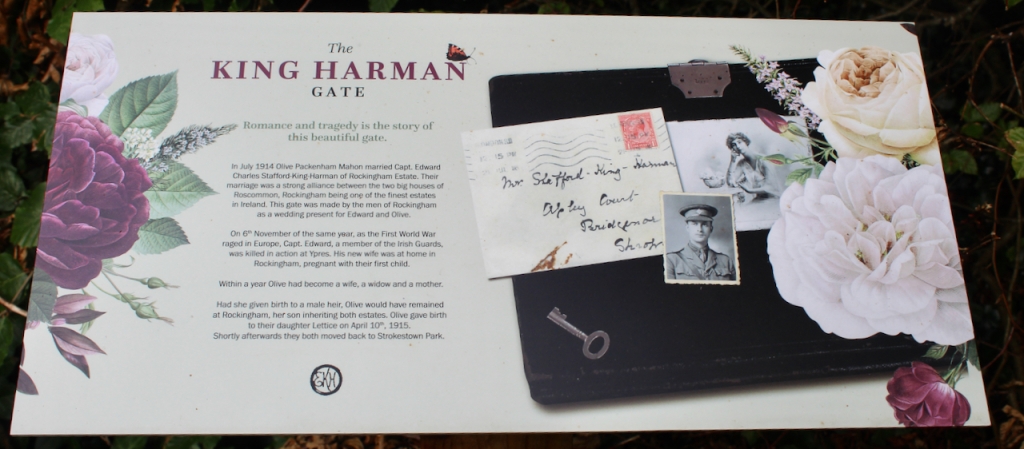

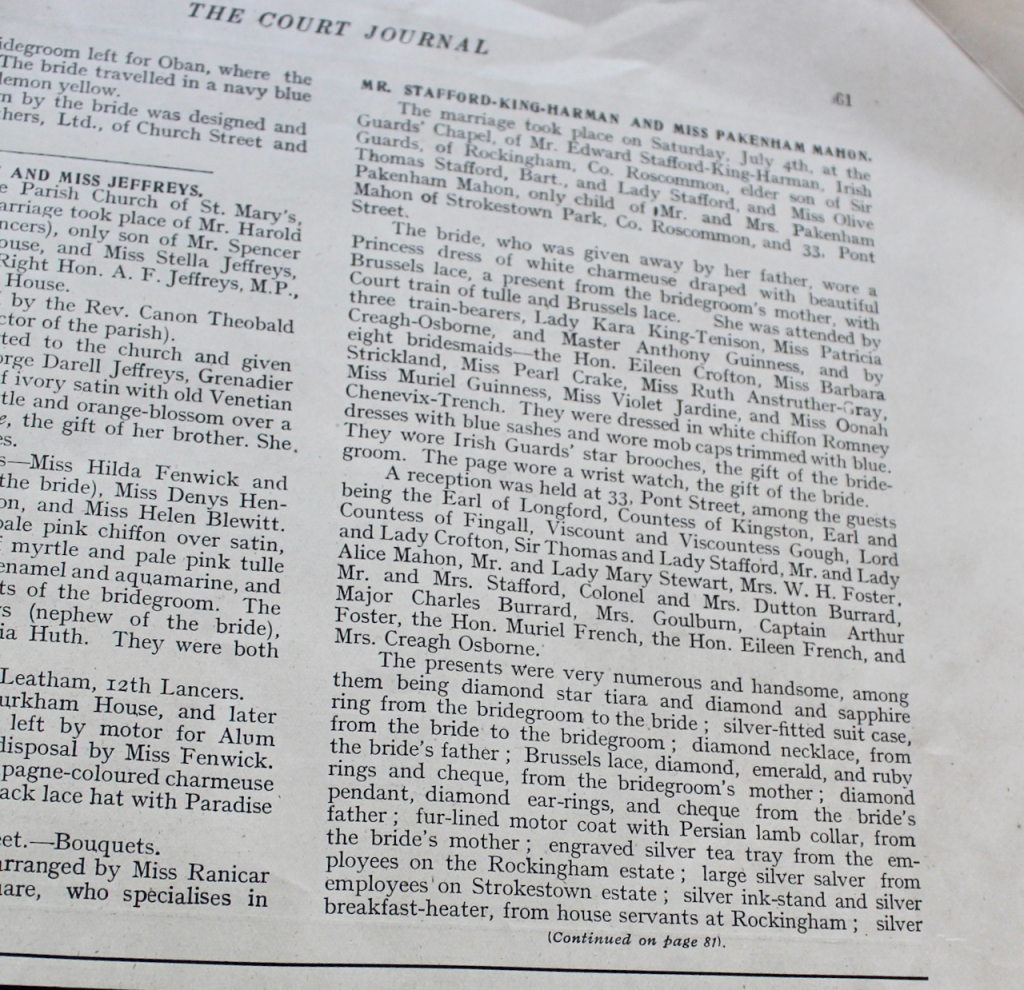

The website previously included a brief history of the inhabitants of Newcastle:

“Newcastle Wood was once part of Newcastle Demesne, an estate of some 11,000 hectares run by the King- Harman family in the 1800’s. The beautiful, historic nearby Newcastle House was where the King- Harmans lived and there are many features and place names in the woodland which refer back to that time.“

We came across Lawrence Harman Parsons (1749-1807) who became the 1st Earl of Rosse, and who added Harman to his surname to become Lawrence Harman Parsons Harman, when he inherited Castlecor in County Longford. He married Jane King, daughter of Edward Thomas King, 1st Earl of Kingston, from Boyle, County Roscommon. They had a daughter, Frances Parsons-Harmon, who married Robert Edward King (1773-1854), 1st Viscount Lorton of Boyle, County Roscommon. Their second son, Lawrence Harman King assumed the additional name of Harman to become Lawrence Harman King-Harman (1816-1875). It was his family who lived at Newcastle Wood.

The old website continued: “The King- Harmans were generally regarded as good landlords by the local populace. They employed many local people in all sorts of trades. The last of the King- Harmans died in 1949. King- Harman sold lands to the Forestry Department in 1934 and over the following two years it was planted with a mixture of coniferous and broadleaf trees.“

Then National Inventory describes the house:

“Detached double-pile seven-bay three-storey over basement former country house, built c. 1730 and altered and extended at various dates throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, having curvilinear Dutch-type gable to the central bay and later gable-fronted single-bay single-storey entrance porch with matching curvilinear Dutch-type gable to the centre of the main block (southeast elevation), built c. 1820. Advanced three-bay single-storey over basement wing flanking main block to northeast, and advanced four-bay two-storey over basement wing flanking main block to southwest, both built c. 1785. Recessed single-bay single-storey over basement Tudor Gothic style addition attached to northeast elevation having gable-fronted rear elevation and chamfered corners at ground floor level having dressed ashlar limestone masonry , built c. 1850, and two-storey extension to southwest, built c. 1880. Possibly incorporating the fabric of earlier house(s) to site c. 1660. Later in use as a convent and now in use as a hotel…Round-headed door opening to front face of porch (southeast) having carved limestone surround with architrave, square-headed timber battened door with decorative cast-iron hinge motifs, wrought-iron overlight, and having moulded render label moulding over.…Painted stuccoed ceilings and ceiling cornices, some with a neoclassical character, a number of early panelled timber doors and marble fireplaces survive to interior...” [5]

Before belonging to the King-Harman family, Newcastle belonged to the Sheppard family. It came to the King-Harman family through the marriage of Frances Sheppard (d. 1766) daughter of Anthony Sheppard of Newcastle to Wentworth Harman (d. 1714) of Moyle, County Longford.

The National Inventory adds:

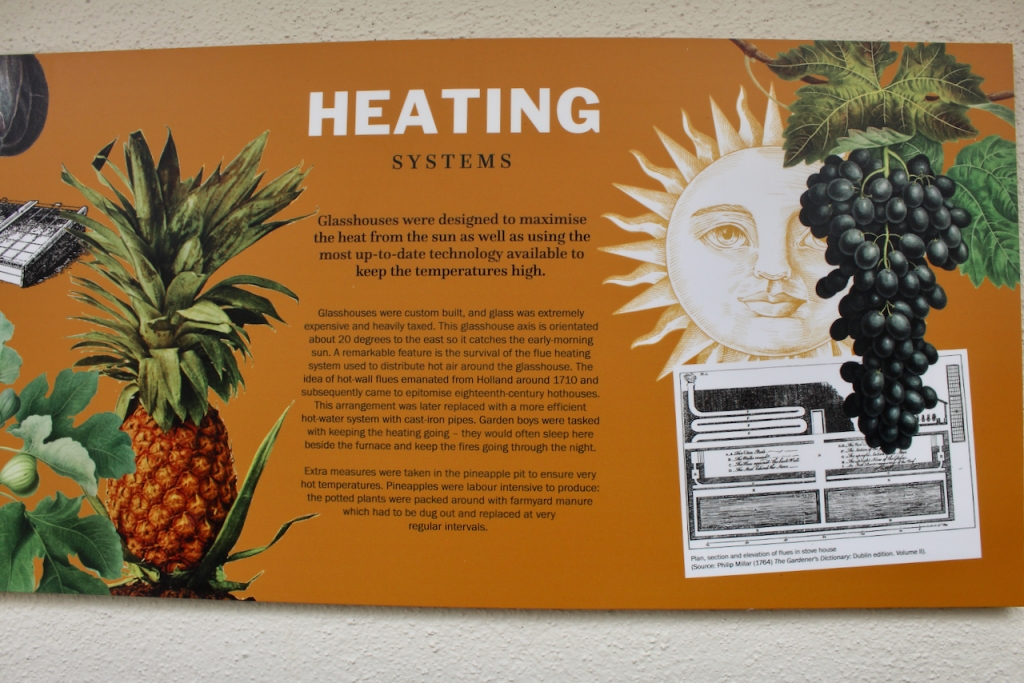

“The lands and house at Newcastle were successively in the possession of the Chappoyne/Chappayne/Choppin, the Sheppard, the Harman and the King-Harman families. The earliest mention of the estate is references to an Anthony Chappoyne at Newcastle in 1660, although this may have been the site of an earlier ‘castle’ from as early as the fourteenth century (as the placename suggests). In 1680 a Robert Choppayne appears to have purchased/consolidated the lands of Newcastle from Gerald Fitzgerald, 17th Earl of Kildare. Dowdall (1682) describes the site as ‘..on the southside of the river is Newcastle, the antient Estate of the Earl of Kildare now the estate and habitation of Robert Choppin Esqr where he hath lately built a fair house and a wooden bridge over said river’. The estate passed into the ownership of Anthony Sheppard (born 1668 – 1738), heir (son?) of Robert Chappoyne, c. 1693, who served as High Sheriff of County Longford in 1698. His son, also Anthony, was M.P. for Longford in 1727. The estate later passed by marriage into the ownership into the Harman family at the very end of the seventeenth century. Robert Harman (1699 – 1765; M.P. for Longford c. 1760 -5) [son of Wentworth Harman and Frances Sheppard] was in possession of the estate of much of the middle of the eighteenth century and it is likely that he was responsible for much of the early work on the house. The Very Revd. Cutts Harman, who built the quirky hunting/fishing lodge at nearby Castlecor, inherited the house c. 1765 following the death of his brother Robert. The estate later passed into the ownership of Lawrence Parsons-Harman (1749 – 1807) in 1784 (M.P. for Longford 1776 – 1792; Baron Oxmantown in 1792; Viscount Oxmantown in 1795; Earl of Rosse 1806; sat was one of the original Irish Representative Peers in the British House of Lords) and he greatly increased the Newcastle estate, and by his death (1807) its size had doubled to approximately 31,000 acres in size. It is likely that he was responsible for the construction of the side wings to the main block and general improvements to the house from 1784. The estate passed into the ownership of his wife Jane, Countess of Rosse (who partially funded the construction of a number of Church of Ireland churches and funded a number of schools in County Longford during the first half of the nineteenth century), who left the estate to her grandson Laurence King-Harman (1816 – 1878) after falling out with her son. Laurence King-Harman has probably responsible for the vaguely Tudor Gothic extension to the northeast elevation. The brick chimneystacks also look of mid-nineteenth century date and may have been added around the same time this wing was constructed. The King family had extensive estates in Ireland during the nineteenth century, owning the magnificent Rockingham House (demolished) and King House [also a Section 482 property which I hope to visit later this year], Boyle, both in County Roscommon; as well as Mitchelstown Castle in County Cork, burnt in 1922 (memorial plaques and carved stone heads from Mitchelstown Castle were built into the northeast elevation of Newcastle House c. 1925, but have been removed and returned to Cork in recent years). The estate reached its largest extent in 1888, some 38,616 acres in size, when Wentworth Henry King-Harman was in residence. The estate was described in 1900 as ‘a master-piece of smooth and intricate organisation, with walled gardens and glasshouses, its diary, its laundry, its carpenters, masons and handymen of all estate crafts, the home farm, the gamekeepers and retrievers kennels, its saw-mill and paint shop and deer park for the provision of venison. The place is self supporting to a much greater degree than most country houses in England’. The estate went in to decline during the first decades of the twentieth century, and with dwindled in size to 800 acres by 1911. The house and estate remained in the ownership of the King-Harman family until c. 1951, when Capt. Robert Douglas King-Harman sold the house to an order of African Missionary nuns (house and contents sold for £11,000). It was later in use as a hotel from c. 1980.” [5]

3. Viewmount House, Longford

The website tells us:

“Discover this boutique gem, a secret tucked away in the heart of Ireland. This magnificent 17th century manor is complemented by its incredible countryside surroundings, and by the four acres of meticulously-maintained garden that surround it. Within the manor you’ll find a place of character, with open fires, beautiful furniture, fresh flowers and Irish literature. The manor retains its stately, historic charm, and blends it with thoughtful renovation that incorporates modern comfort.

“Here, you will unwind into the exceptionally relaxing atmosphere, a restful world where all you hear is peace, quiet and birdsong.“

This house was advertised for sale in recent years. The National Inventory describes it:

“Detached three-bay three-storey house, built c. 1750 and remodeled c. 1860, having single-bay single-storey porch with flat roof to the centre of the front elevation (north). Renovated c. 1994. Formerly in use as a Church of Ireland charter school (c. 1753 – 1826)…This elegant mid-sized Georgian house is a fine example of the language of classical architecture reduced to its essential elements. It retains its early character and form despite recent alterations….Set in extensive mature grounds, this fine structure is a worthy addition to the architectural heritage of County Longford….This house was the home of the Cuffe family during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was later inherited by Thomas Pakenham (later [1st] Baron Longford [of Pakenham Hall, or Tullynally, County Westmeath, another section 482 property, see my entry]) following his marriage to Elizabeth Cuffe (1714-94) in 1739 or 1740. It is possible that Viewmount House was constructed shortly after this date and it may have replaced an earlier Cuffe family house on or close to the present site. The house was never lived in by the Pakenham family but it was used by their agent to administer the Longford estate, c. 1860. It was apparently in use as a charter school from 1753 until 1826, originally founded under the patronage of Thomas Pakenham. There is a ‘charter school’ indicated here (or close to here) on the Taylor and Skinner map (from Maps of the Roads of Ireland) of the area, dated between 1777 – 1783. A ‘free charter school’ at Knockahaw, Longford Town, with 32 boys, is mentioned in an Irish Education Board Report, dated 1826 – 7 (Ir. Educ. Rept 2, 692 – 3).” [6]

[2] p. 66. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[3] www.irishhistorichouses.com/2020/12/10/kilshannig-house-rathcormac-county-cork/