Sorry, this is another re-publishing, as it was previously published on my “Places to Visit in County Antrim” page. Stephen and I have still been too busy this year to visit more Section 482 properties. Heritage Week is coming up next month, August 17-24th, so all of the Section 482 properties should be open – see my home page for details, https://irishhistorichouses.com/

I hope Stephen and I can visit many properties this year during Heritage Week!

The website tells us that Glenarm Castle is one of few country estates that remains privately owned but open to the public. It is steeped in a wealth of history, culture and heritage and attracts over 100,000 visitors annually from all over the world.

“Visitors can enjoy enchanted walks through the Walled Garden and Castle Trail, indulge in an amazing lunch in the Tea Room, purchase some local produce or official merchandise, or browse through a wide range of ladies & gents fashions and accessories and a selection of beautiful gifts, souvenirs and crafts in the Byre Shop and Shambles Workshop – with many ranges exclusive to Glenarm Castle.“

“Glenarm Castle is the ancestral home of the McDonnell family, Earls of Antrim. The castle is first and foremost the private family home of Viscount and Viscountess Dunluce and their family but they are delighted to welcome visitors to Glenarm Castle for guided tours on selected dates throughout the year.

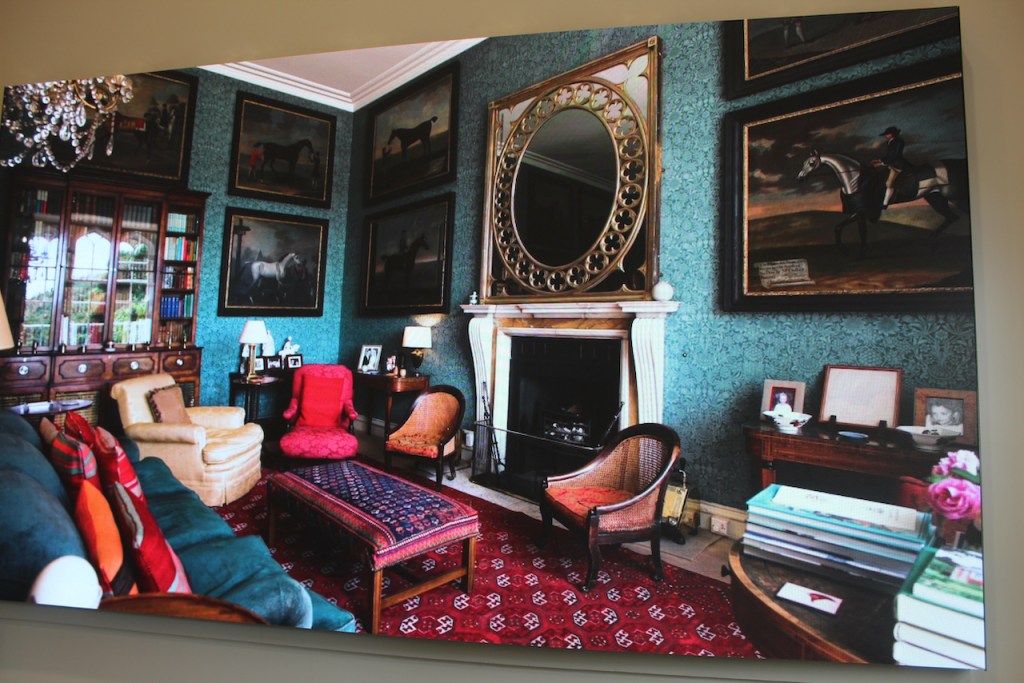

“Delve deep into the history of Glenarm Castle brought to life by the family butler and house staff within the walls of the drawing room, the dining room, the ‘Blue Room’ and the Castle’s striking hall.

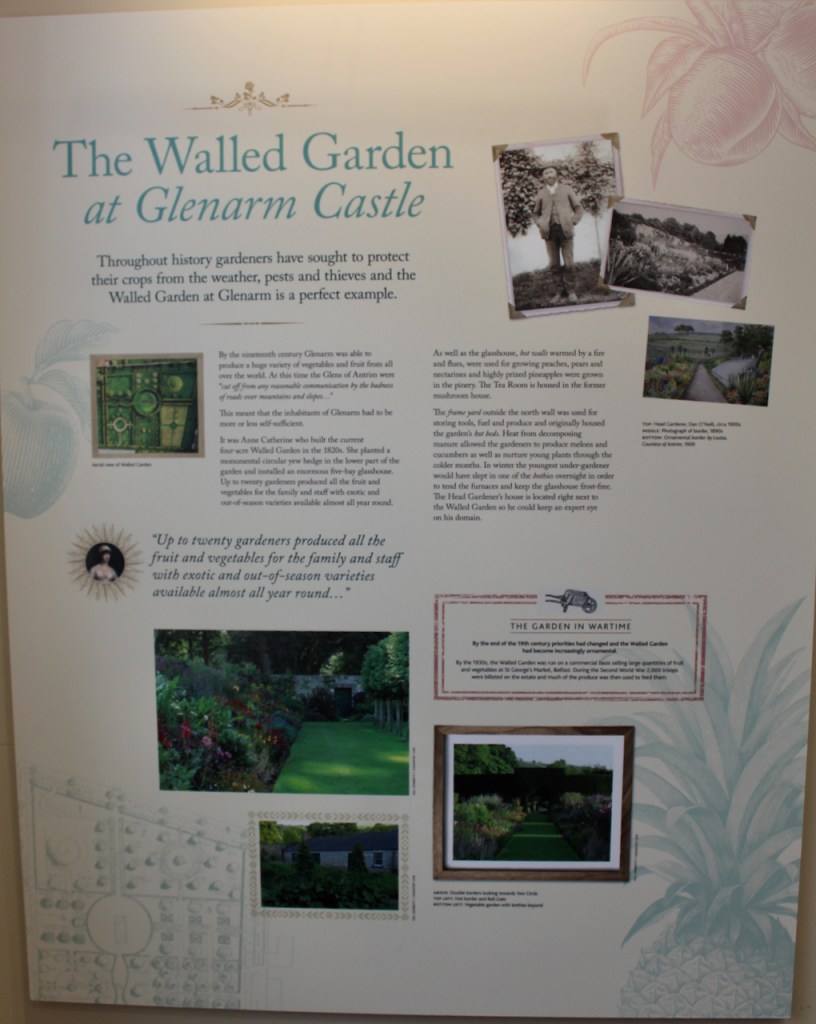

“Finish the day with the glorious sight of the historic Walled Garden, which dates back to the 17th century.“

Dates are limited and booking in advance is required.

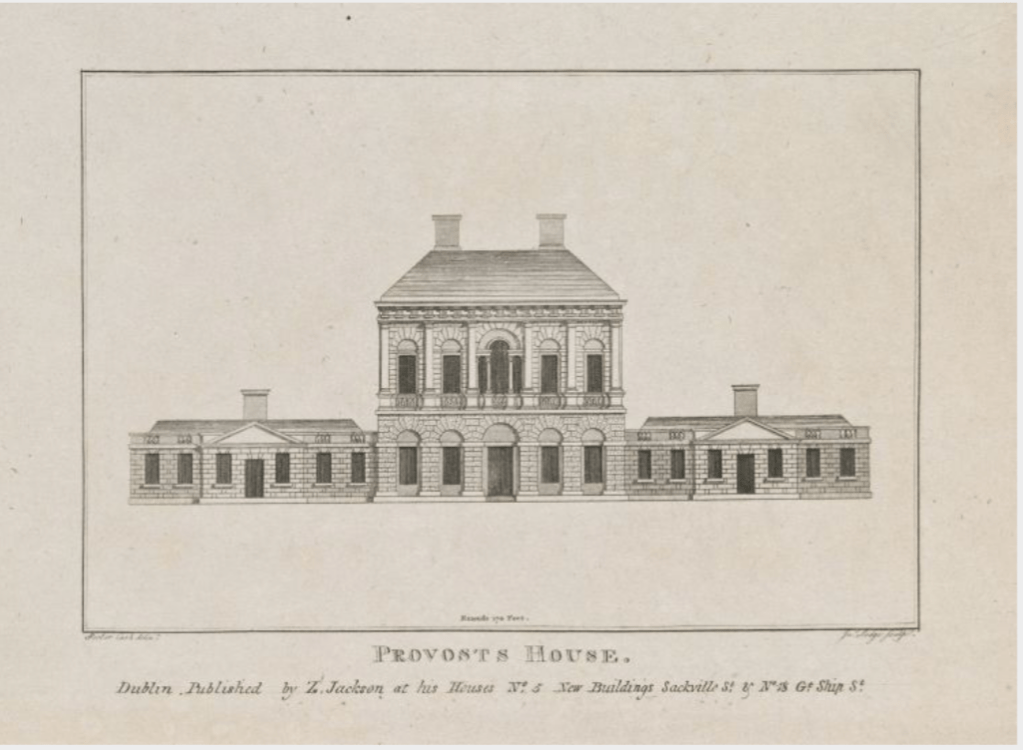

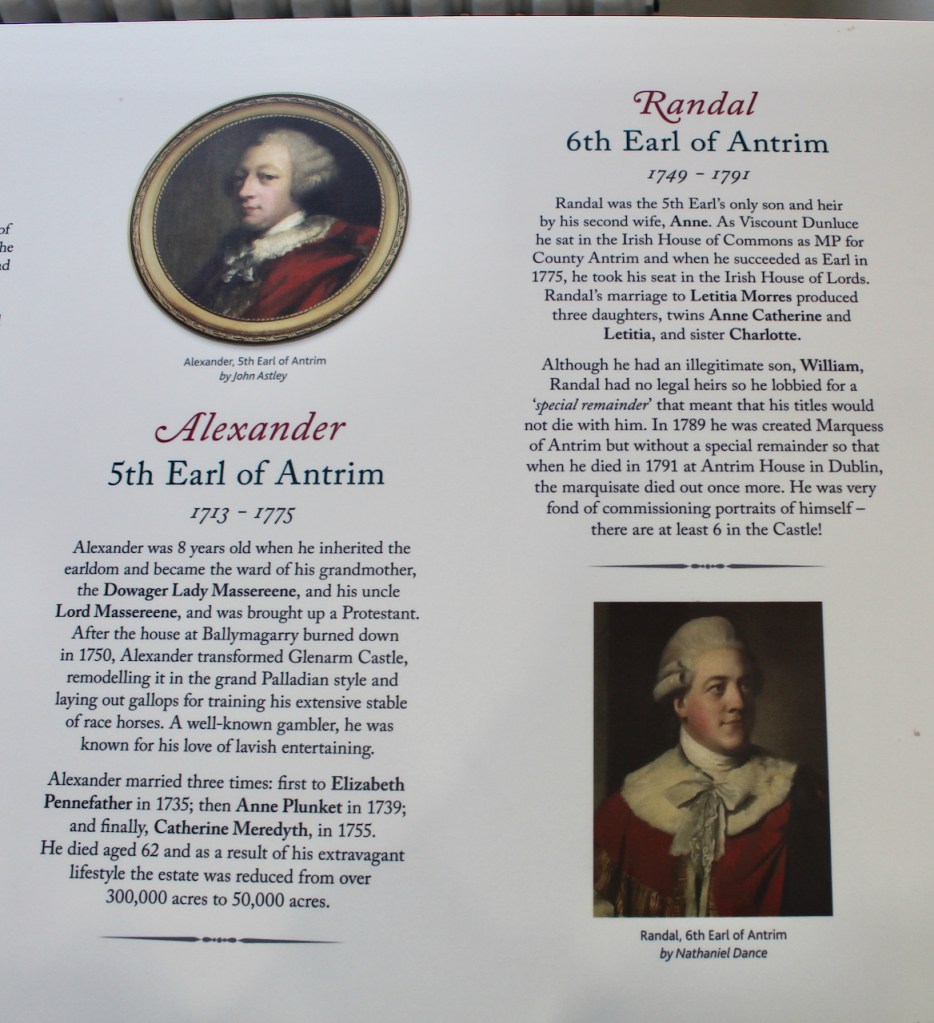

The castle was built around 1603 by Randal MacDonnell [1610-1682], afterwards 1st Earl of Antrim, as a hunting lodge or secondary residence to Dunluce Castle, and became the principal seat of the family after Dunluce Castle was abandoned. The mansion house was rebuilt ca. 1750 as a 3-storey double gable-ended block, joined by curving colonnades to two storey pavilions with high roofs and cupolas. This would have been during the life of the 5th Earl of Antrim, Alexander MacDonnell (1713-1775).

We learned of the 1st and 2nd Earls of Antrim on our visit to Dunluce Castle in Antrim. When the 2nd Earl died in 1682 his brother Alexander (1615-1699) became 3rd Earl of Antrim. He first married Elizabeth Annesley, daughter of the 1st Earl of Anglesey.

Elizabeth née Annesley died in 1672 and Alexander married Helena Burke. Their son Randal (1680-1721) became the 4th Earl of Antrim.

The 4th Earl married Rachael Skeffington, daughter of Clotworthy, 3rd Viscount Massereene, Co. Antrim, of Antrim Castle. The 4th Earl of Rachael had a son Alexander MacDonnell (1713-1775) who succeeded as 5th Earl of Antrim. It was during his time that the castle was enlarged. He was a Privy Counsellor and Governor of County Antrim.

Ballymagarry, where the Earls lived after Dunluce Castle, burned down in 1750, so in 1756 the 5th Earl of Antrim invited an engineer from Cumbria called Christopher Myers to come to Glenarm to rebuild the ruin. Myers transformed it into a grand Palladian country house with curving colonnades ending in pavilions on either side, one of which contained a banqueting room. The lime trees that now arch over the driveway were planted and gardens were planned in a network of walled enclosures.

Alexander the 5th Earl married Elizabeth Pennefather, daughter of Matthew, MP for Cashel and Comptroller and Accountant-General for Ireland. She died, however, in 1736, and he married Anne Plunkett in 1739.

Anne née Plunkett gave birth to the heir, Randal William (1749-1791), who later became the 6th Earl of Antrim. Anne died when Randall was just six years old, so Alexander married again, this time to Catherine Meredyth, daughter of Thomas of Newtown, County Meath. She had been previously married to James Taylor (1700-1747), son of Thomas 1st Baronet Taylor, of Kells, Co. Meath.

The 6th Earl served as MP for County Antrim as well as High Sheriff for the county. Randall William MacDonnell married Letitia Morres, daughter of Hervey Morres 1st Viscount Mountmorres of Kilkenny. They had no sons.

Randall William was created 1st Viscount Dunluce [Ireland] and 1st Earl of Antrim [Ireland] on 19 June 1785, with special remainder to his daughters in order of seniority. This meant that his daughters became Countesses of Antim in their own right. He then served as Privy Counsellor for Ireland. He was created 1st Marquess of Antrim [Ireland] on 18 August 1789 but this title died with him, along with the two earlier creations of Earl of Antrim and Viscount Dunluce.

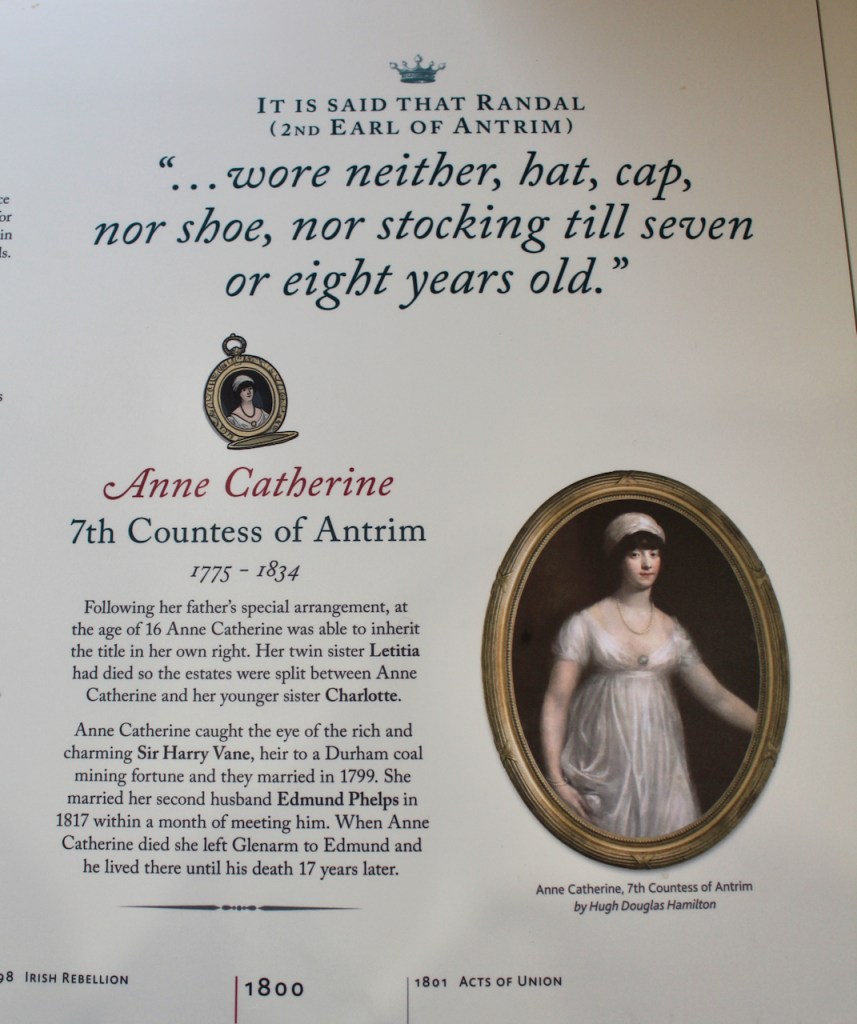

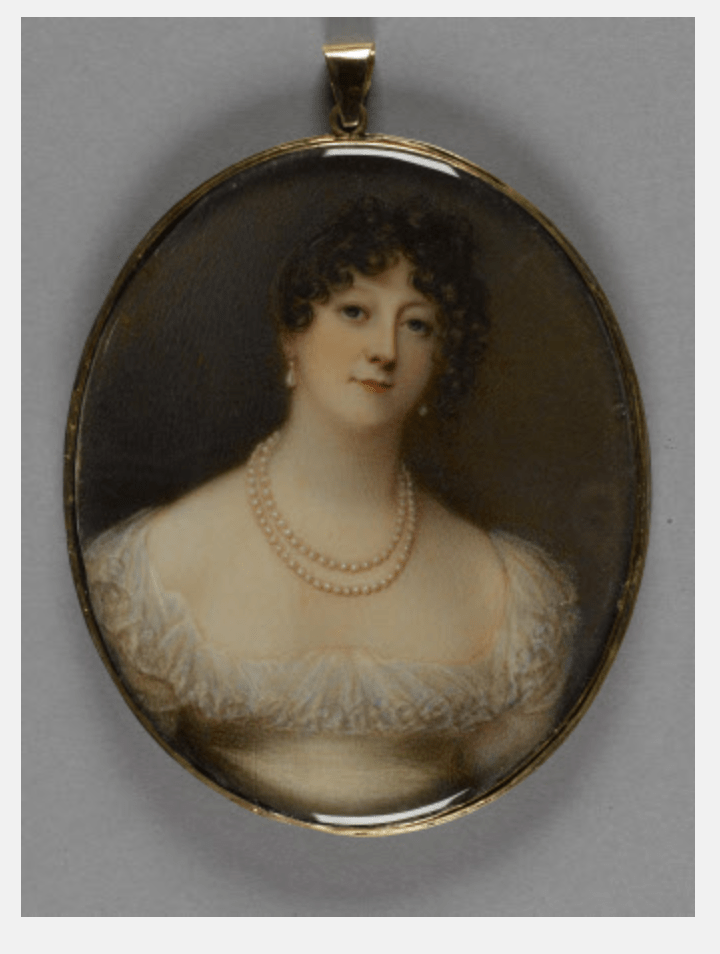

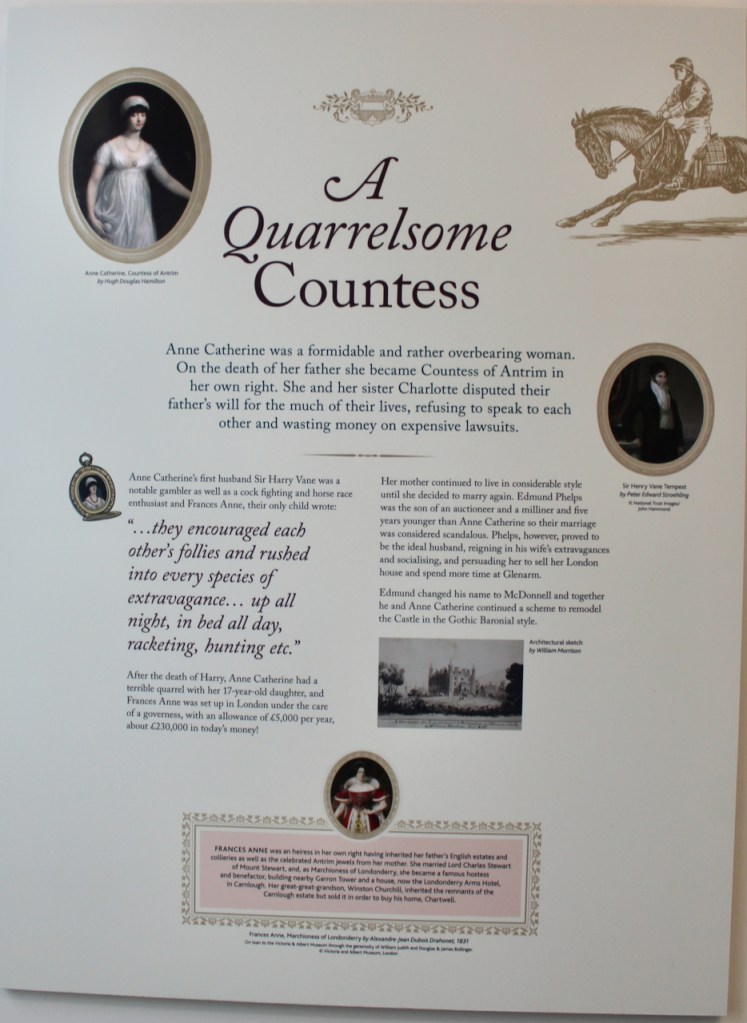

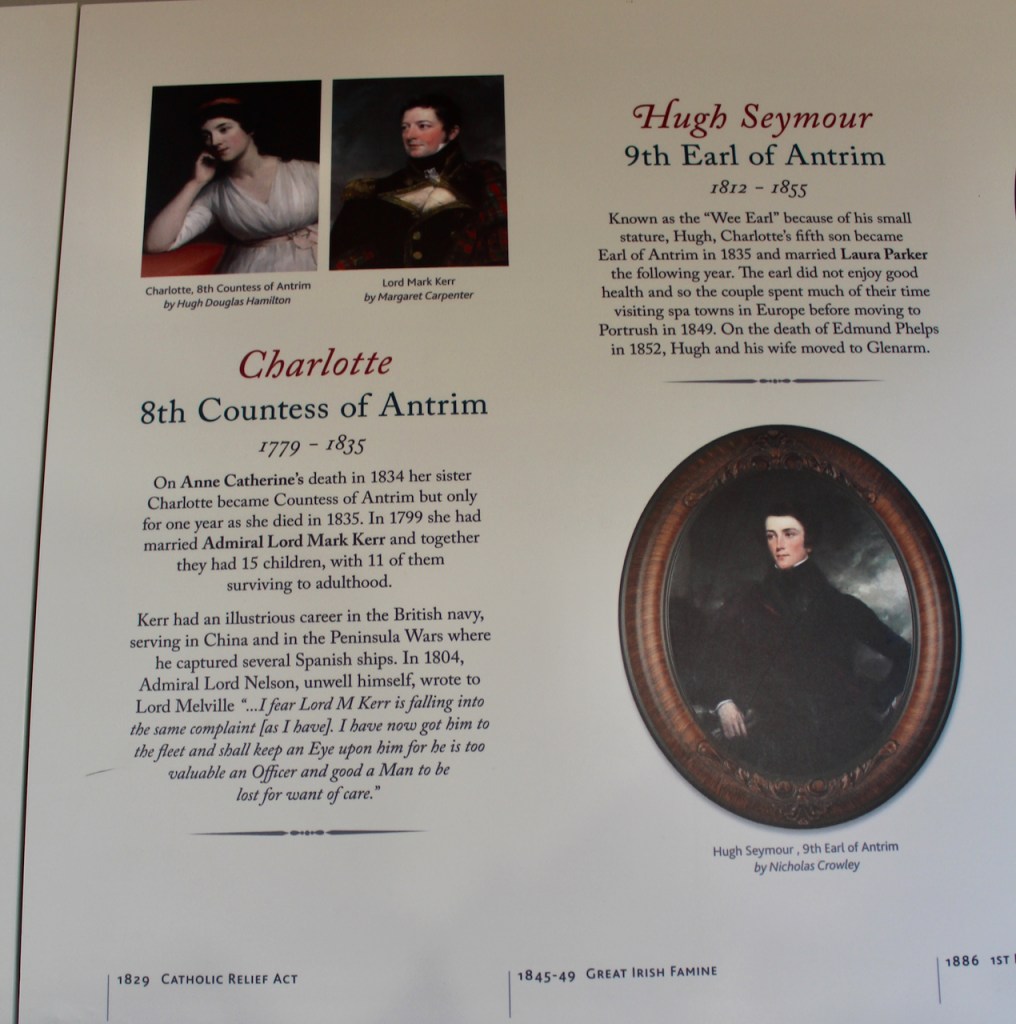

His eldest daughter Anne Catherine (1778-1834) became 2nd Countess of Antrim in 1791 when her father died. Anne Catherine’s sister Letitia Mary predeceased her. When Anne Catherine died in 1834 her sister Charlotte became 3rd Countess of Antrim. Charlotte’s sons became the 4th and 5th Earls of Antrim (the Countesses being in lieu of the 2nd and 3rd Earls). The descendants still live in the castle.

See also the blog of Timothy William Ferres. [2]

Anne Catherine married first Henry Vane-Tempest (1771-1813) 2nd Baronet Vane, of Long Newton, Co. Durham. They had a daughter, Frances Anne Emily Vane-Tempest, who married Charles William Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry. Harry Vane-Tempest decided to ‘Gothicise’ the building. The colonnades and pavilions were demolished and Gothic windows installed. When he died, Anne Catherine married Edmund Phelps, who assumed the name of MacDonnell.

Anne Catherine and Edmund hired William Vitruvius Morrison to enlarge Glenarm.

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 135. “(McDonnell, Antrim, E/PB) …The main block had a pedimented breakfront with three windows in the top storey, a Venetian window below and a tripartite doorway below again, flanked on either side by a Venetian window in each of the two lower storeys and a triple window above. The pavilions were of three bays. Ca. 1825, the heiress of the McDonnells, Anne, Countess of Antrim in her own right, and her second husband [Edmund Phelps], who had assumed the surname of McDonnell, commissioned William Vitruvius Morrison to throw a Tudor cloak over Glenarm. He did very much the same as he had done at Borris, Co Carlow and Kilcoleman Abbey, Co Kerry; adding four slender corner turrets to C18 block, crowned with cupolas and gilded vanes; he also gave the house a Tudor-Revival façade with stepped gables, finials, pointed and mullioned windows and heraldic achievements, as well as a suitably Tudor porch. The other fronts were also given pointed windows and the colonnades and pavilions were swept away, a two storey Tudor-Revival service wing being added in their stead.” [3]

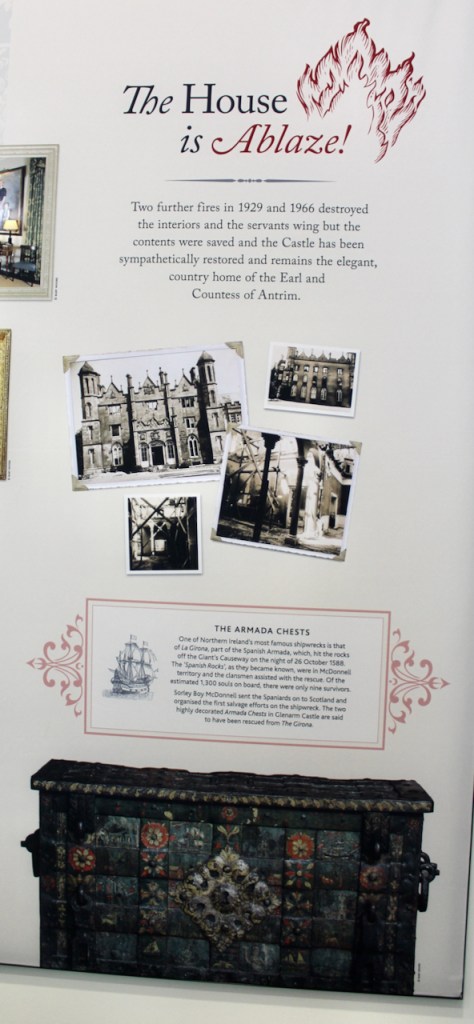

Mark Bence-Jones continues:”The interior remained Classical; the hall being divided by an arcade with fluted Corinthian columns; the dining room having a cornice of plasterwork in the keyhole pattern. In 1929, the Castle was more or less gutted by fire; in the subsequent rebuilding, to the designs of Imrie & Angell, of London, the pointed and mullioned windows were replaced with rectangular Georgian sashes. Apart from the octagon bedroom, which keeps its original plasterwork ceiling with doves, the interior now dates from the post-fire rebuilding; some of the rooms have ceilings painted by the present Countess of Antrim [Elizabeth Hannah Sacher]. The service wing was reconstructed after another fire 1967, the architect being Mr Donal Insall. In 1825, at the same time as the castle was made Tudor, the entrance to the demesne from the town of Glenarm was transformed into one of the most romantic pieces of C19 medievalism in Ireland, probably also by Morrison. A tall, embattled gate tower, known as the Barbican, stands at the far end of the bridge across the river, flanked by battlemented walls rising from the river bed.” [3]

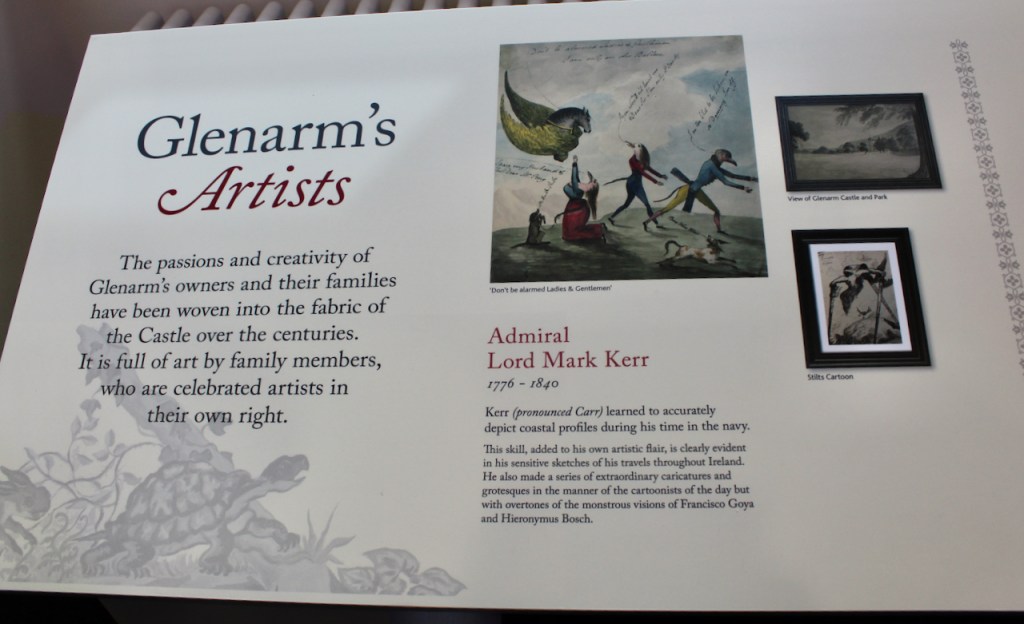

The second daughter, Charlotte 3rd Countess of Antrim married Mark Robert Kerr (1776-1840), son of William John Kerr, 5th Marquess of Lothian, Scotland. An information board tells us that as well as being a military man, he had a fondness for art.

Charlotte and Mark had many children. Their sons who inherited the title Earl of Antrim after their mother’s death took the name MacDonnell when they succeeded to the title. The 4th Earl, Hugh Seymour McDonnell (1812-1855) had no son so his brother, Mark (1814-1869), succeeded him as 5th Earl of Antrim.

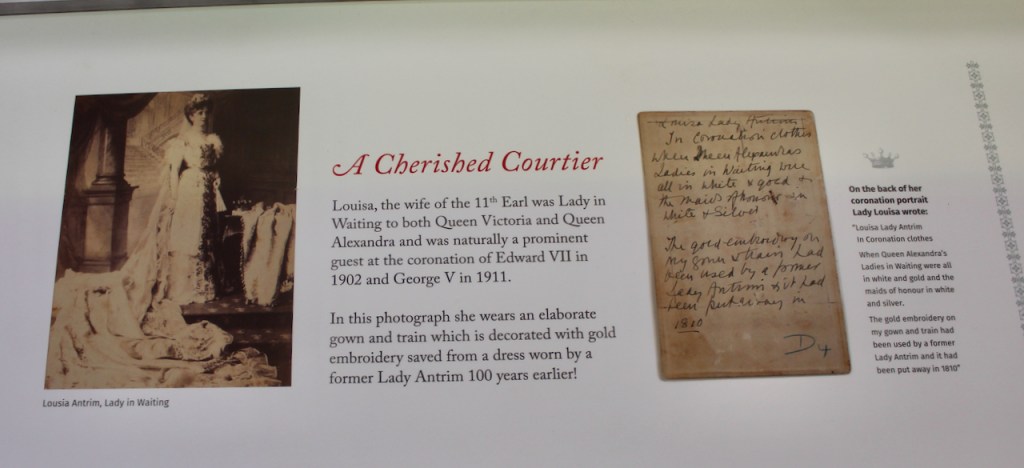

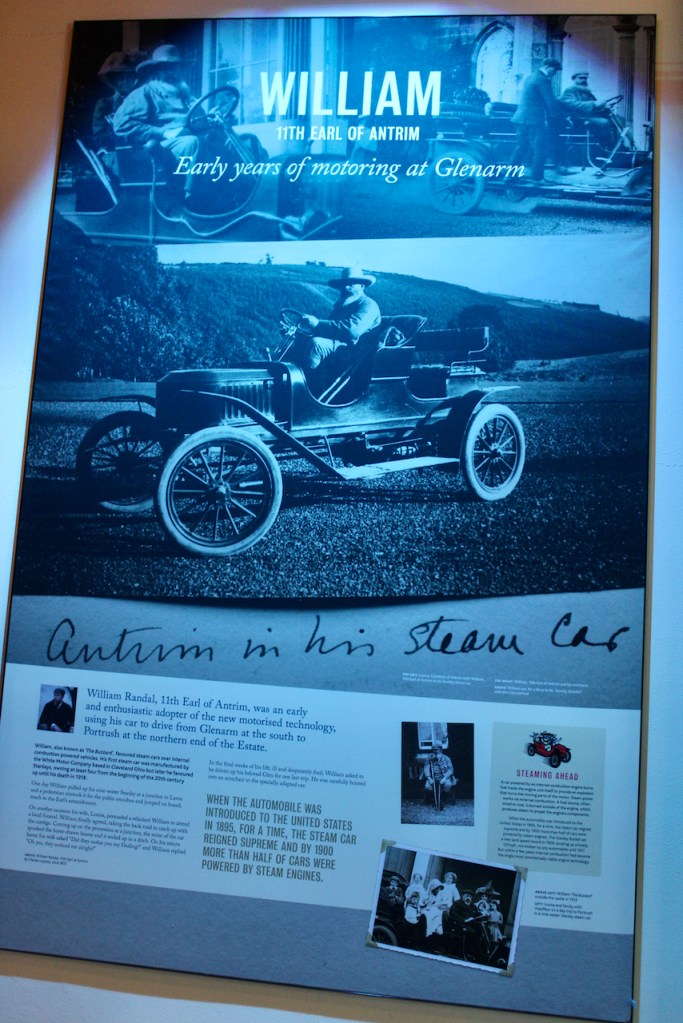

Mark’s son William Randal McDonnell (1851-1918) succeeded as 6th/11th Earl of Antrim. He held the office of Deputy Lieutenant (D.L.) of County Antrim. In the information panel in the museum at the castle, he is referred to as the 11th Earl. He married Louisa Jane Grey. She held the office of a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Victoria between 1890 and 1901.

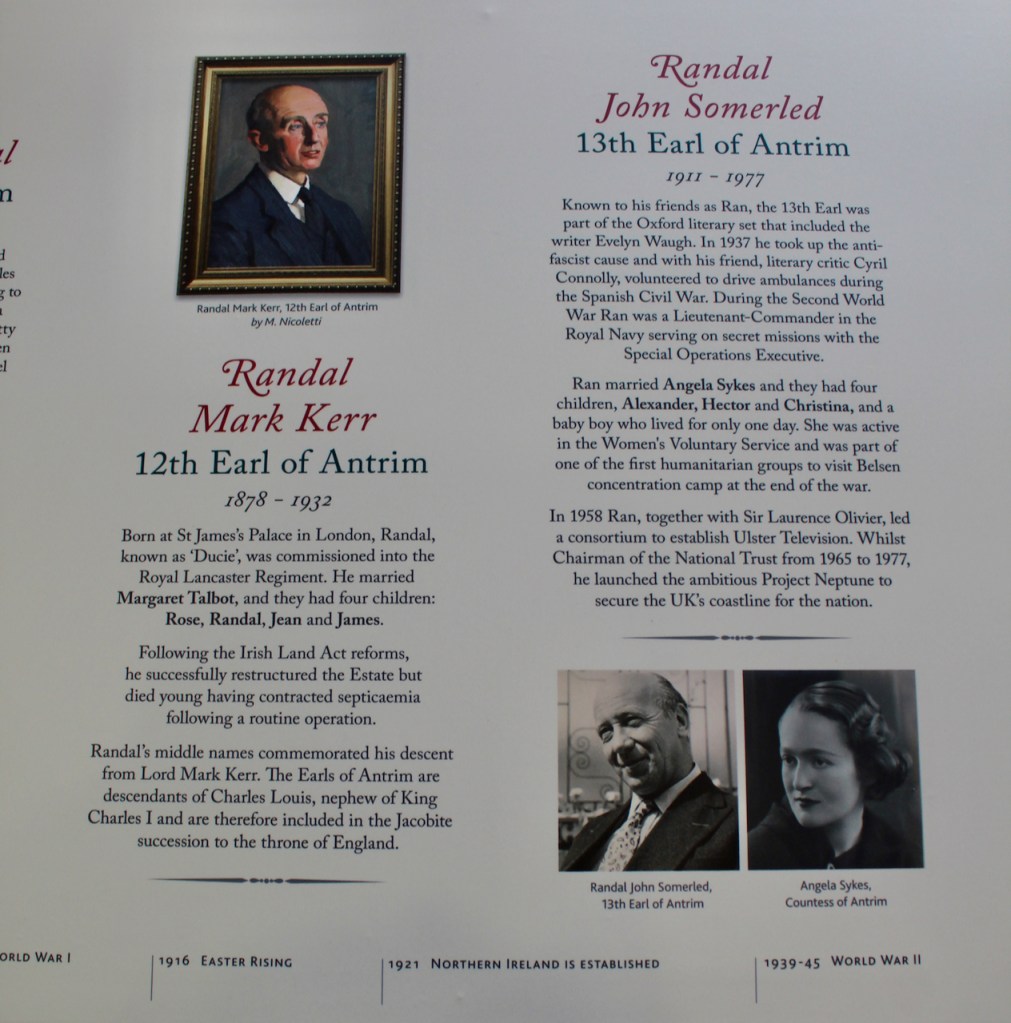

Their son Randal Kerr MacDonnell (1878-1932) became 7th/12th Earl of Antrim in 1918. In 1929 a large fire occurred.

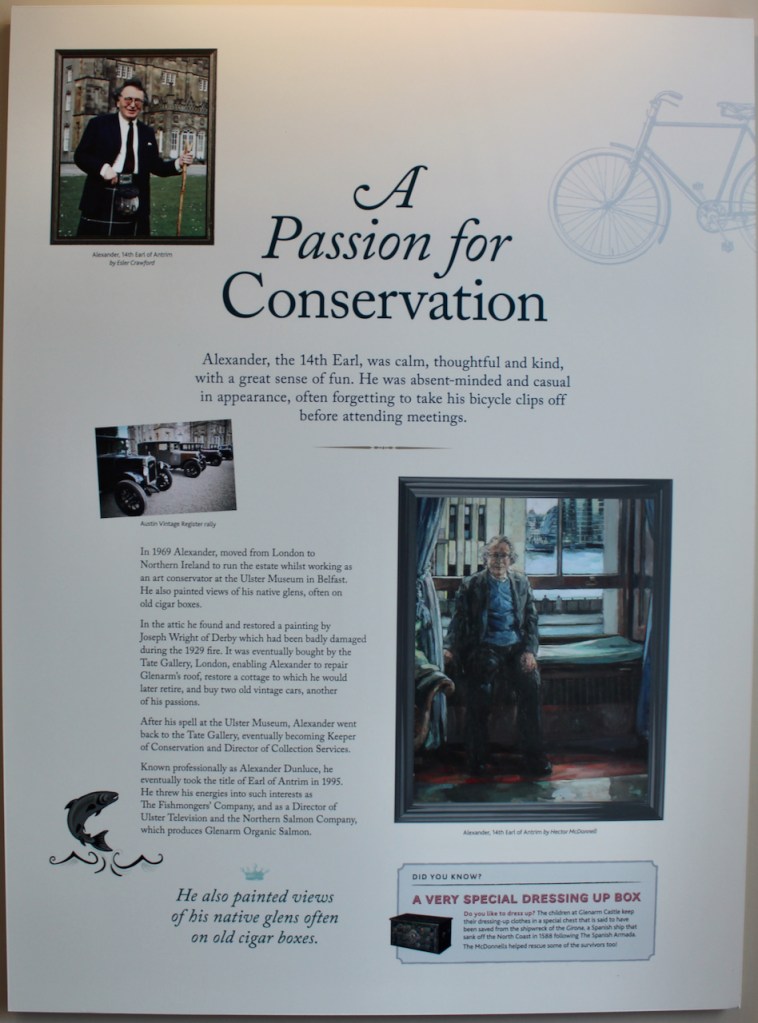

His son Randal John (1911-1977) became 8th Earl (13th) in 1932, and his son in turn, Alexander Randal MacDonnell (1935-2021) the 9th Earl.

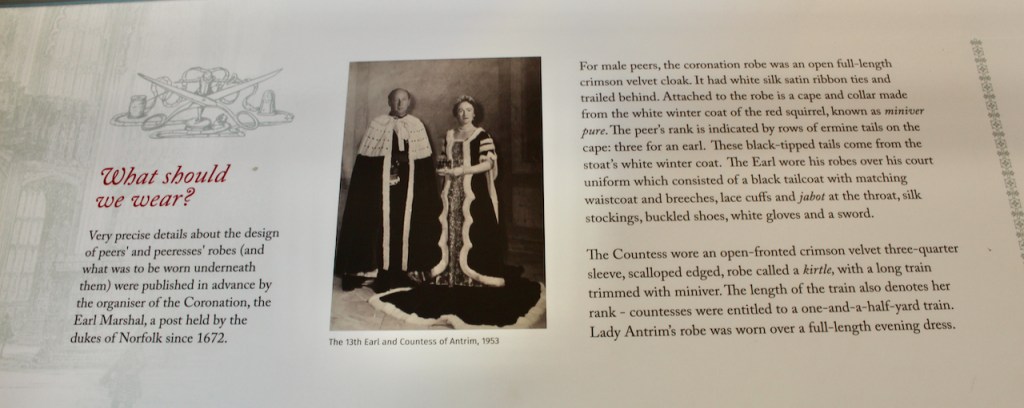

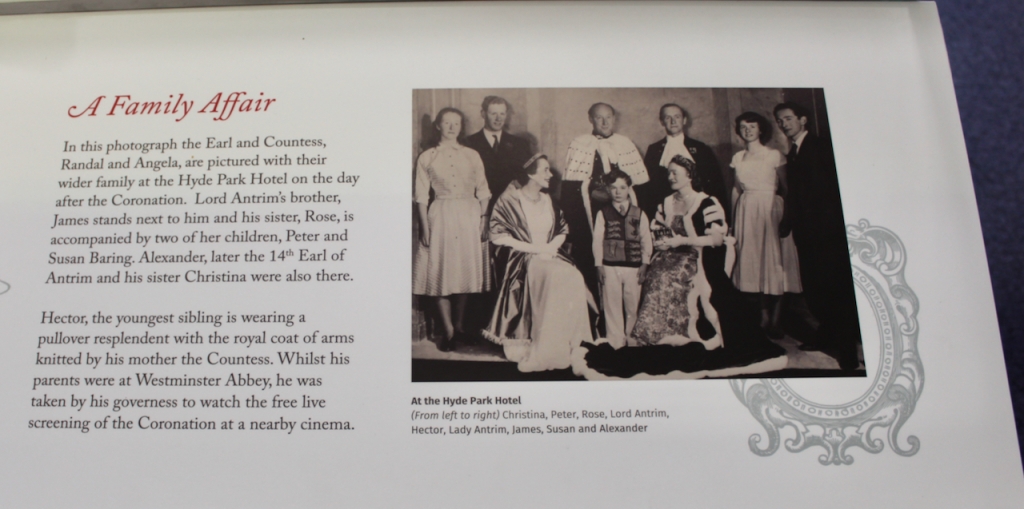

Randal John 8th Earl and his wife Angela attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

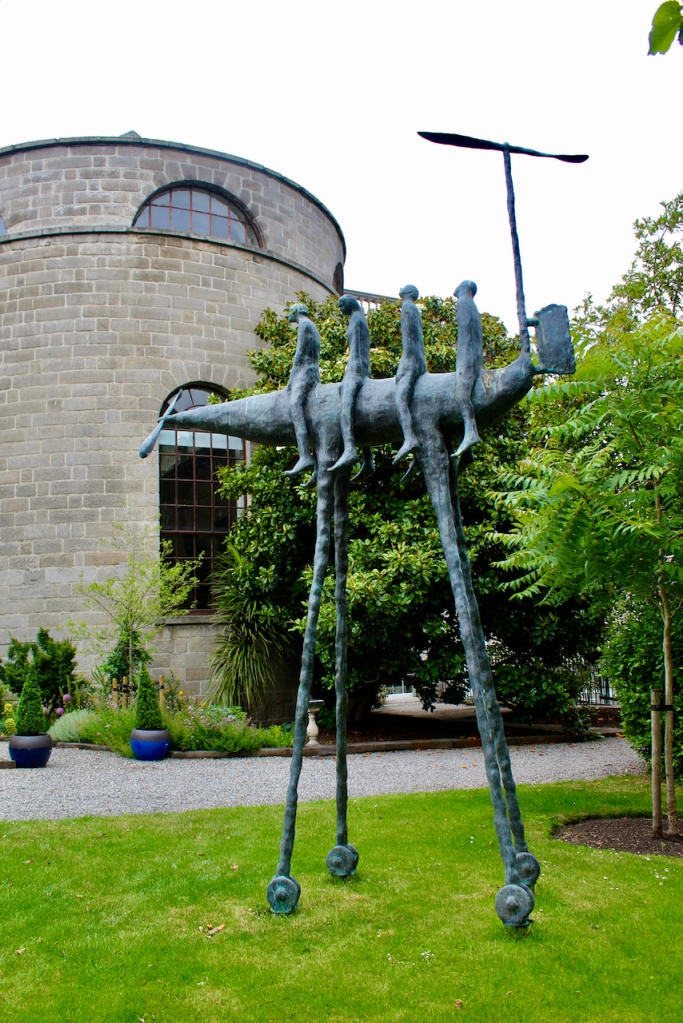

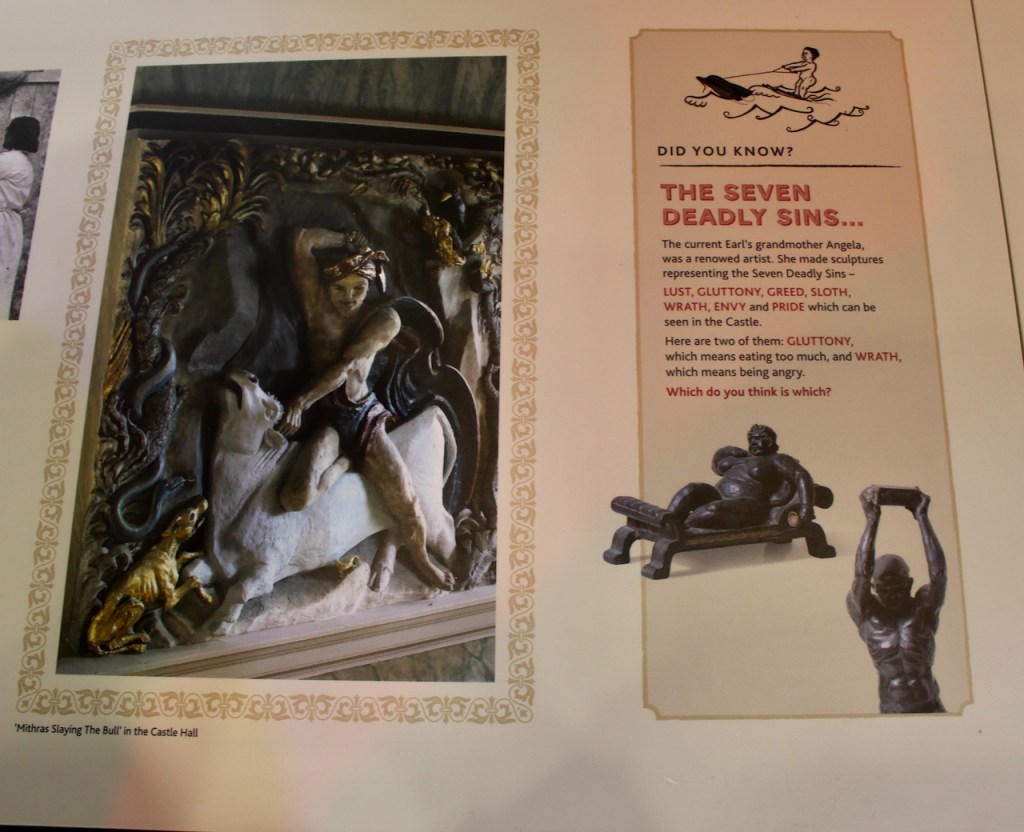

Angela Sykes (1911-1984), wife of the 8th or 13th Earl was an artist and she created the rather bulging statues of planetary gods that adorn the ceiling corners of the front hall. She also designed Mithras slaying the bull over the fireplace. She also created murals in the dining room, drawing room and in her bedroom.

The Castle also hosts a Coach House Museum.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[3] p. 135, Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com