Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My website costs €300 per year on WordPress.

€15.00

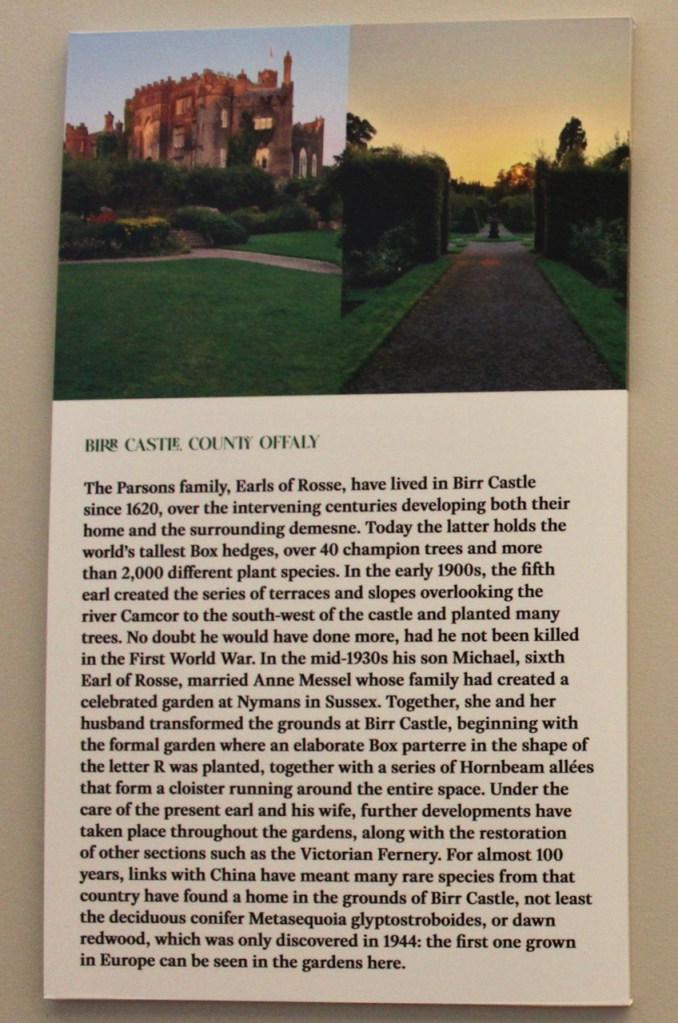

Open dates in 2026: May 15-30, June 1-6, 8-13, 15-20, 22-27, 29-30, July 1-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1-5,

11am-3pm

Fee: €22 each castle tour and garden

We visited Birr Castle in June 2019. I am dying to visit again!

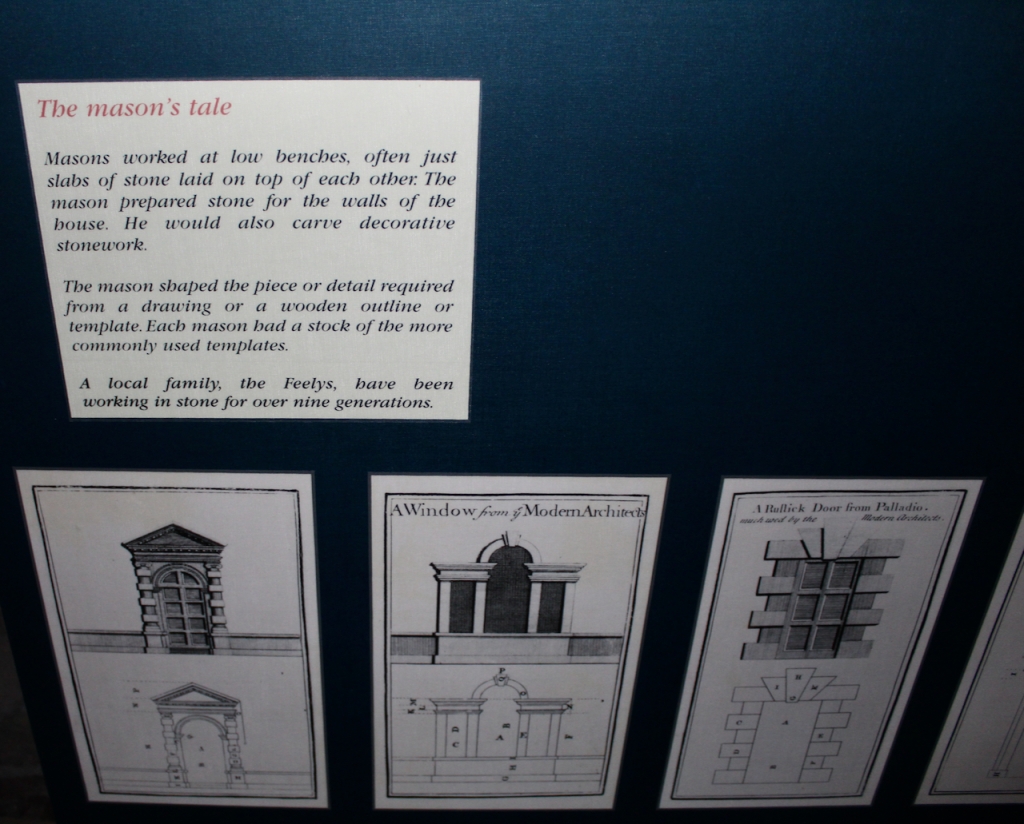

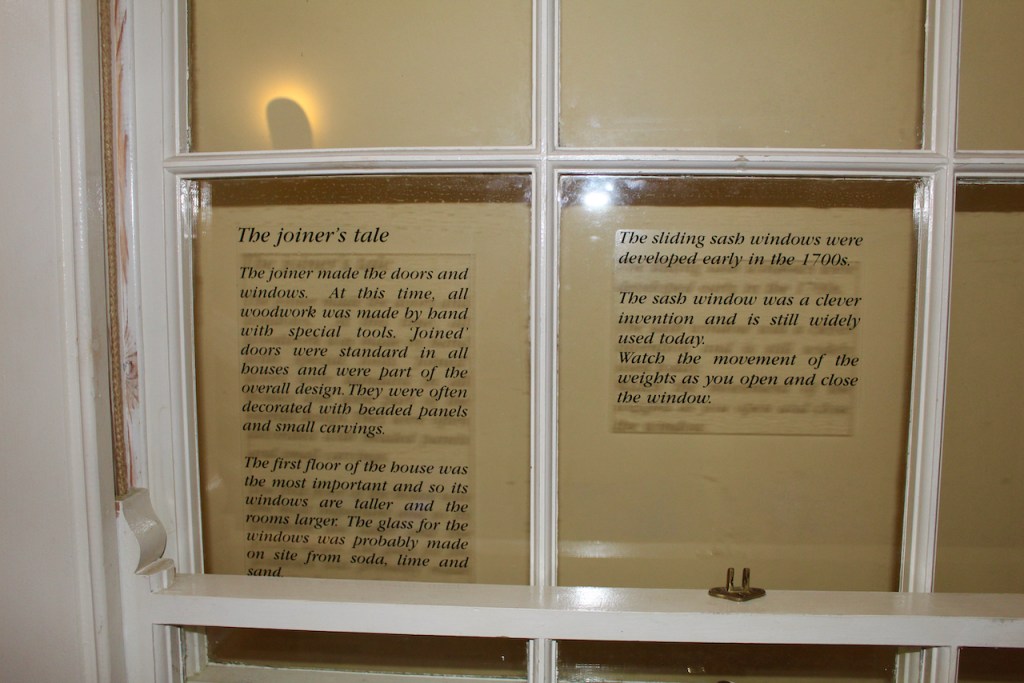

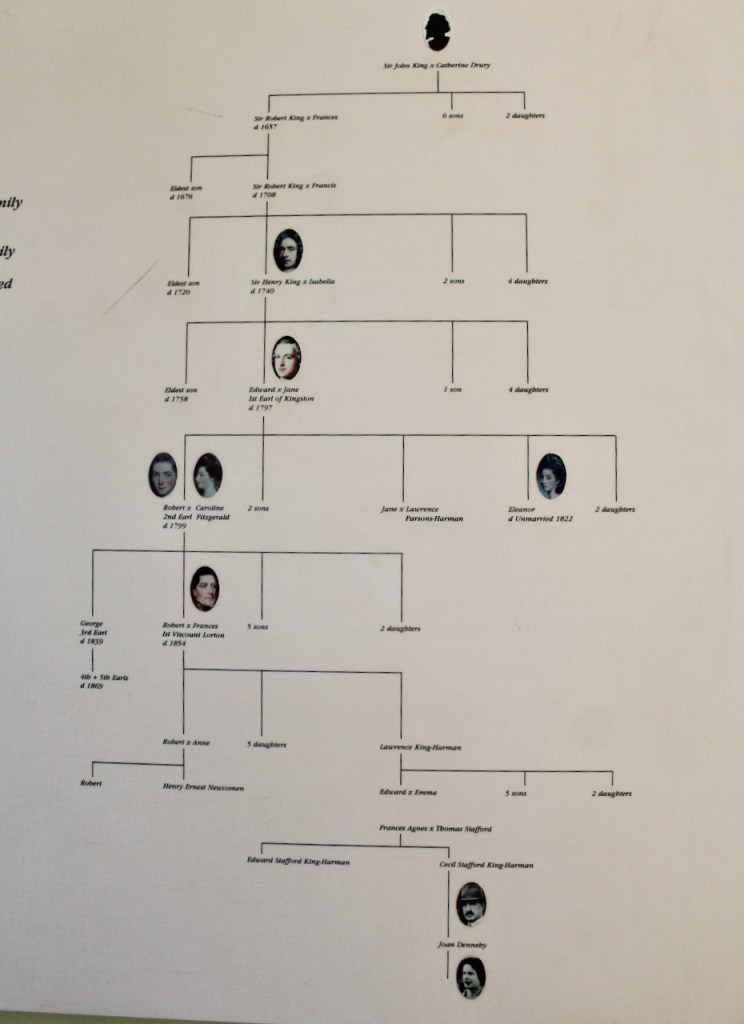

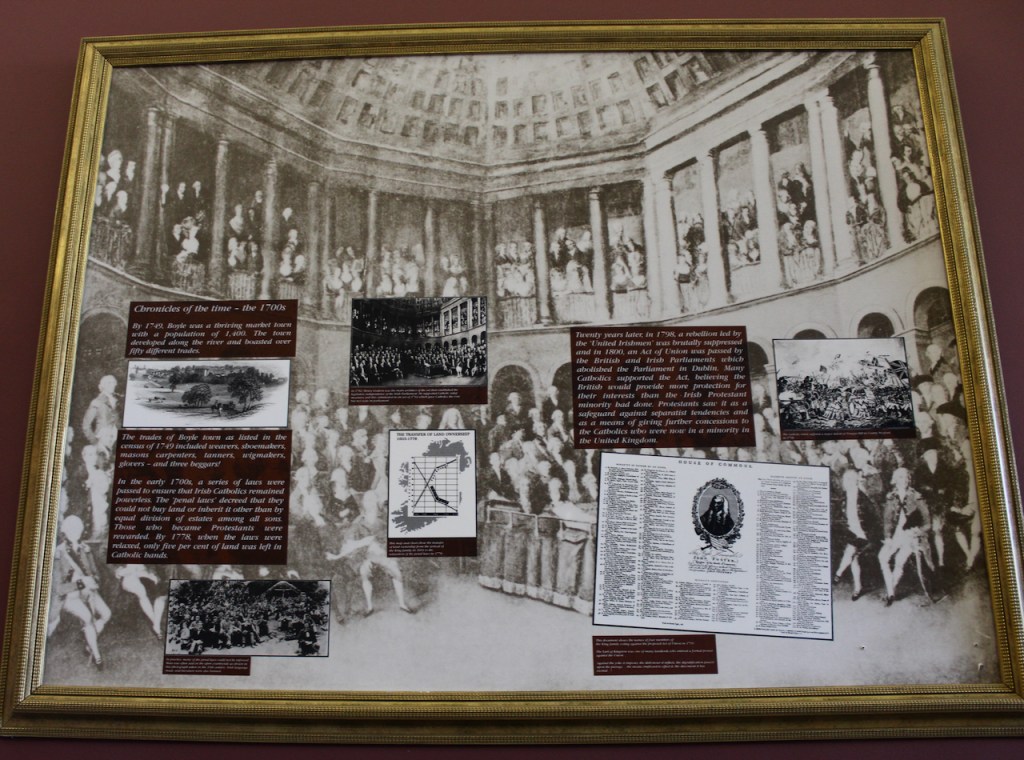

The castle has been in the one family since 1620. A castle existed on the site before then, but little remains of the original, as the old O’Carroll keep and the early C17 office ranges were swept away around 1778. However, parts of the auxiliary buildings of the original are incorporated into today’s castle, which was made from the gate tower which led into the castle bawn. The front hall of the original gatehouse is now at basement level. The rest of the castle has been built around this, at various times.

The castle formed part of a chain of fortresses built by the powerful O’Carroll family of Ely, on the borders of Leinster and Munster. In the 1580s the castle was sold to the Ormond Butlers. By 1620 the castle was a ruin, and King James I granted it to Laurence Parsons (d. 1628). [2] It was Laurence who made the current castle originating from the gate tower.

Although still a private residence, it is well set up for tours of the castle, and the demesne is wonderful for walks. The current owner is William Parsons, 7th Earl of Rosse.

The Parsons still live in the castle today and maintain the archives. According to the website:

“The Rosse papers are one of the most important collections of manuscripts in private ownership in Ireland. Extending from the early seventeenth century, when members of the family first established roots in the country, to the present, the core of the family archive is provided by the papers of successive members of the Parsons family. This calendar is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of: seventeenth and eighteenth-century Ireland; science in the nineteenth century; the British navy in the eighteenth century; the evolving story of the surviving families of the Irish landed elite in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and in the influence of a particular family that contrived over a number of centuries not only to transform Birr into one of the country’s most elegant small towns, but also to construct and sustain one of the finest country houses and its gardens.Access to the archives is by appointment.” [3]

In Crowned Harp, Memories of the Last Years of the Crown in Ireland, Nora Robertson writes about her ancestor Laurence Parsons:

“With the further connivance of his even less admirable brother [less admirable, that is, than Laurence Parson’s kinsman Richard Boyle], Lord Justice William Parsons, Laurence acquired the forfeited estates of the Ely O’Carrolls in Offaly, whither he moved and erected Birr Castle...” [4]

The family history section of the Birr Castle website explains that there were four Parson brothers living in Ireland in the 1620s. They came to Ireland around 1590, and were nephews of Sir Geoffrey Fenton, Secretary of State in Ireland to Queen Elizabeth I. [5] Laurence’s brother William (1570-1649/1650) became Surveyor General of Ireland, 1st Baronet, and founded the elder branch of the Parson family in Bellamont, Dublin. This branch died out at the end of the eighteenth century.

William was known as a “land-hunter”, expropriating land from owners whose titles were deemed defective. William was the progenitor of the first generation of the title of Earl of Rosse. When the last male to hold that title died without heirs, after a time the title passed to the descendants of the first baronet Bellamont’s younger brother, Laurence Parsons of Birr Castle.

Before obtaining land in Offaly, through his connection with Richard Boyle later 1st Earl of Cork (Richard married Catherine Fenton, daughter of Geoffrey Fenton, Secretary of State in Ireland to Queen Elizabeth I), Laurence Parsons acquired Myrtle Grove in Youghal, Co. Cork, previously owned by Walter Raleigh, and succeeded Raleigh as Mayor of Youghal.

Raleigh, who introduced tobacco to Europe after discovering it on his travels, had a bucket of water thrown over him by a housemaid when he was smoking, as she thought he was on fire! Raleigh is also said to have planted the first potato in Ireland.

Laurence Parsons served as Attorney General of Munster and later, Baron of the Exchequer, and was knighted in 1620. That same year, he ‘swapped’ his interest in a property near Cadamstown in County Wexford with Sir Robert Meredith, who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Ireland, for the latter’s 1,000 acres at Birr, Kings County. Parsons was granted letters patent to ‘the Castle, fort and Lands of Birr.’ [see 5]

The castle website states that:

“rather than occupy the tower house of the O’Carrolls, the Parsons decided to turn the Norman gate tower into their ‘English House,’ building on either side and incorporating two flanking towers. Sir Laurence Parsons did a large amount of building and remodelling including the building of the two flanking towers, before his death in 1628. This is all accounted for in our archives.” [6]

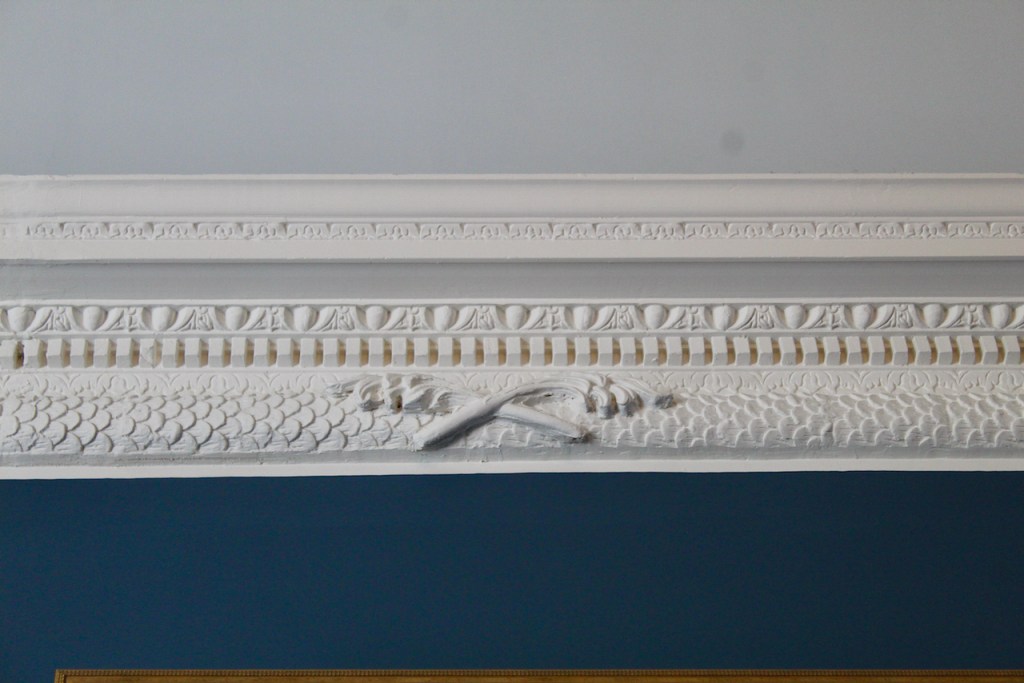

Suitably, a room which is now the castle’s Muniments room, which holds the archives, is located inside one of the flanking towers and retains a frieze of early 17thcentury plasterwork.

Our guide walked a group of us over to the castle, across the moat, which he told us had been created in 1847 when the owners of Birr Castle provided employment to help to stave off the hunger of the famine, along with the enormous walls surrounding the castle demesne as well as the stone stable buildings, which are now the reception courtyard, museum and cafe.

I was intrigued to hear that the gates had been made by one of the residents of the castle, Lady Mary Field, wife of William Parsons, the third Earl of Rosse. She was an accomplished ironworker! She was also a photographer. She brought a fortune with her to the castle when she married the Earl of Rosse, which enabled him to build his telescope, for which the estate is famous. But more on that later.

Family crests from families who intermarried with the Parsons of Birr are also worked into the gate. There are similar crests on the ceiling of the front hallway of the castle.

We were not allowed to take photos inside the castle, unfortunately. On the other hand it’s always a relief when I am told I cannot take photos, for it means I can relax and really look, and listen to the tour guide.

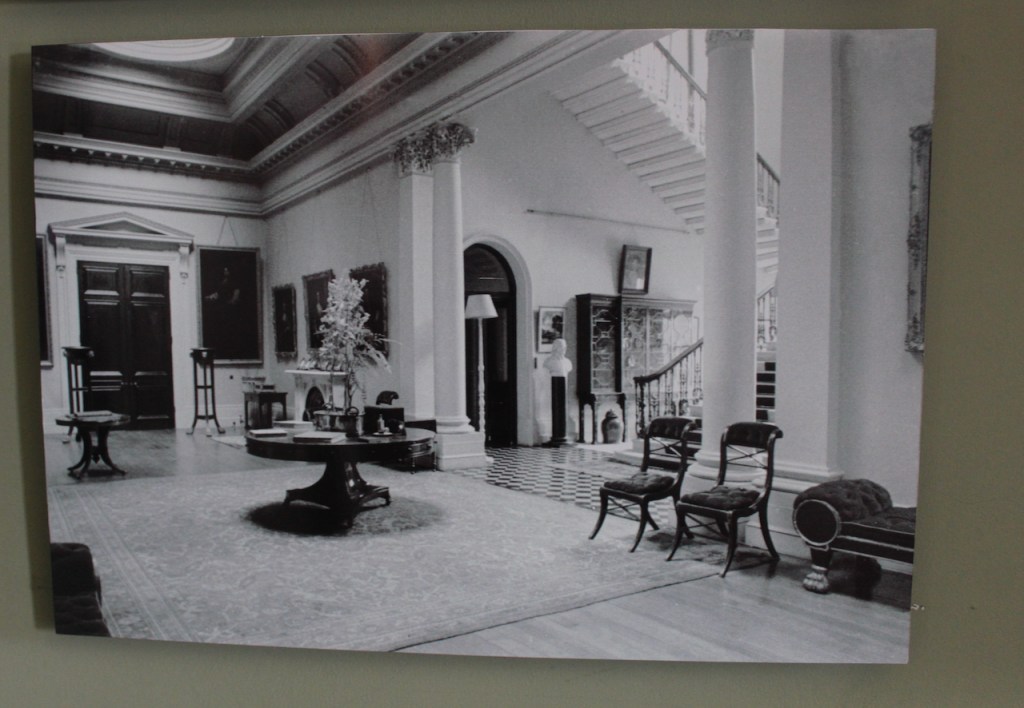

With the help of portraits, our guide described the Parson family’s ancestors. The entrance hall, the room over the arch in the original gatehouse, has some portraits and a collection of arms.

The principal staircase is from the 17th century house, and is built of native yew. It was described in 1681 by Thomas Dinely as “the fairest in all Ireland.” It rises through three storeys, and is heavy, with thick turned balusters and a curving carved handrail. The ceiling above the stairs has plaster Gothic vaulting and dates from the reconstruction after a fire in 1832.

Sir Laurence’s son Richard succeeded his father in 1628. Richard died in 1634 without an heir so Birr Castle passed to Richard’s brother William (d. 1653). During his time in Birr Castle, William protected the castle from a siege in 1641 during the Catholic uprising. He fought off the forces for fourteen or fifteen months but eventually surrendered in January 1642/43. [Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage p. 1721] The family moved to London, returning at the end of the Cromwellian period.

In his will, William specified that when the Birr estate is worth £1000 per year, his heir should build an alsmhouse in Birr for four aged Protestants, each with a garden and orchard and enough grass for the grazing of two cows. The beneficiaries would be given 12 pence every Sunday, freedom to cut turf for fire, and a red gown with a badge once every two years, which was to be presented by the heir.

William’s heir was his son, Laurence Parsons (d. 1698), who married Lady Frances, youngest daughter and co-heir of William Savage Esquire of Rheban, County Kildare.

This Laurence Parsons has a substantial entry in The Dictionary of Irish Biography. He was created Baronet of Birr Castle in 1677. Under the lord deputyship of Tyrconnell, Irish protestant grew nervous about another Catholic uprising, and Parsons moved his family to England in 1687. He left a tenant and servant of long standing, Heward Oxburgh, in charge of his estate, with instructions to use his rentals to pay certain debts, and to remit payments to him in England.

Oxburgh was a Catholic who had lost land and been transplanted to Connaught, but was a tenant and servant of the Parsons for thirty years by 1692.

When the rental money did not materialise, Parsons returned to Ireland. He found his agent “highly advanced to the dignity of sheriff of the county, who lorded it over his neighbours at a great rate, and was grown and swollen to such a height of pride he scarce owned his master.” (Birr Castle MSS, A/24, ff 1–2). Furthermore, Oxburgh had used the estate’s rental income to raise a regiment of foot soldiers for King James II.

Parsons reoccupied his castle, which was then besieged by Oxburgh’s forces. Under duress he signed articles, only to find himself tried for treason against William III, and sentenced to death. Imprisoned in his castle, he was reprieved from execution several times, and eventually in April 1690 he was moved to Dublin, and was released shortly after the battle of the Boyne.

Oxburgh sat for King’s County in the Irish parliament summoned by James II in 1689, while his son Heward was returned for Philipstown. He died in the Battle of Aughrim in 1691.

Parsons was again appointed high sheriff of King’s County, and returned to Birr to secure the area against Jacobites and tories. He was involved in one notable skirmish on 11 August, before returning to Dublin to meet his wife and children who had travelled from England. Birr was subsequently occupied by Williamite forces.

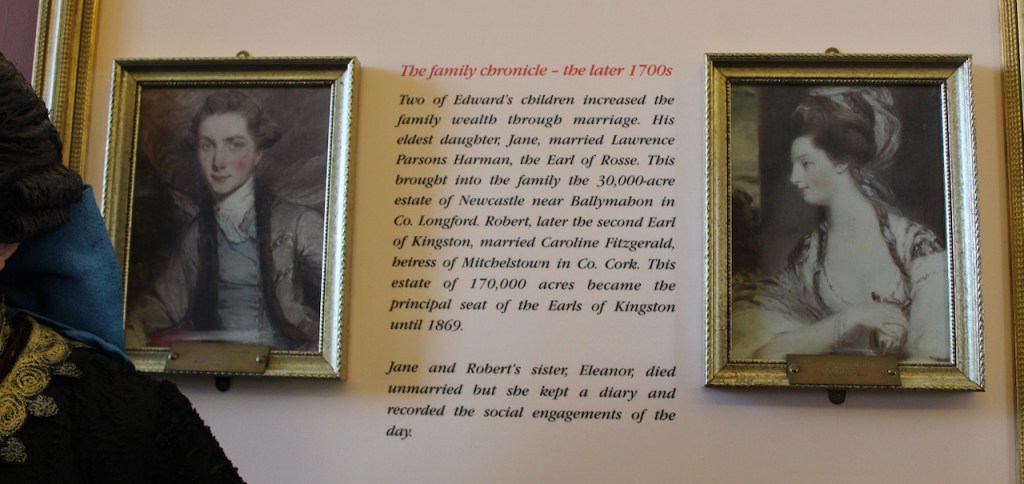

Laurence Parsons died in 1698 and was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son, William Parsons (d. 1740) 2nd Baronet. William served in the Williamite forces, and was MP for King’s Co. (1692–1741). He married firstly Elizabeth, daughter of a Scottish Baronet, and they had one son. This son William Parsons married Martha Pigott and they had a son, Laurence (1707-1756). William Parsons 2nd Baronet died in 1740 and his grandson Laurence Parsons (1707-1756) succeeded as 3rd Baronet of Birr Castle.

Lawrence Parsons 3rd Baronet married Mary Sprigge in 1730. They had one son, William (1731–1791). Laurence died in 1749 and was succeeded in the baronetcy by his eldest son by his first marriage, William Parsons (1731–1791) who became 4th Baronet.

The Third Baronet married again in 1742, marrying Anne Harman, daughter of Wentworth Harman of County Longford, and had two more sons, Laurence and Wentworth. Laurence (1749-1807), inherited his uncle Cutts Harman’s estate County Longford with the proviso that he take the name Harman, to become Laurence Harman Parsons. In 1792 he was raised to the Peerage of Ireland as Baron of Oxmantown, in County Dublin and in 1795, Viscount Oxmantown. In 1806 when he was created Earl of Rosse in the Irish peerage, of the second creation.

The title of Earl of Rosse came from the elder branch of the family, from the descendants of William Parsons (1570-1649/1650), 1st Baronet of Bellamont. Rosse refers to New Ross in County Wexford.

Let us go back and look at the descendants of William Parsons (1570-1649/1650), 1st Baronet of Bellamont. First, let’s look at the machinations of William himself, the “land hunter.” The Dictionary of Irish Biography details his activities:

“his conduct as supervisor of various plantations outraged the numerous native landowners who were dispossessed by his highly questionable legal machinations: local juries were intimidated into invalidating titles to property, while those dispossessed who sought legal recourse were ruined by expensive and time-consuming counter-suits. From 1611 to 1628 he was heavily involved in the increasingly crude efforts by the government to wrest land in Cosha and Ranelagh, Co. Wicklow, from Phelim McFeagh O’Byrne, which culminated in a failed attempt to frame O’Byrne for murder by torturing witnesses. He also encountered criticism for the manner in which he exercised his office as surveyor of plantation land by deliberately underestimating the extent of plantation land in order to defraud the crown and the church of their revenues. At least twice he had to procure royal pardons for corrupt activities.

“By these means, he furthered the crown’s policy of supplanting catholic landowners with more politically reliable protestant ones while personally acquiring prime plantation land in Co. Wexford, Co. Tyrone, and Co. Longford, and in King’s Co. (Offaly) and Queen’s Co. (Laois). Although his grasping nature was widely advertised in Ireland, he escaped royal censure due to his political clout, being a key member of a powerful and tightly knit group of Dublin-based government officials who enriched themselves by obstructing and redirecting royal grants of Irish lands intended for courtiers in London. Reflecting his political influence and widening property interests, he sat as MP for Newcastle Lyons (1613–15), Armagh Co. (1634–5) and Wicklow Co. (1640–41).“

Parsons’s fortunes changed when Thomas Wentworth came as Lord Deputy to Ireland. Wentworth believed that the protestant establishment was hopelessly corrupt and had failed in its civilising mission in Ireland. He instigated legal proceedings – designed to recover property for the crown – against a number of prominent protestant landowners.

Parsons managed to keep in favour to an extent with Wentworth, although they did not trust each other, and when Wentworth was subsequently accused in 1640 of corruption and treason, Parsons was appointed Lord Justice of Ireland. Parsons knew he stood on shakey ground, however, due to his complicity with Wentworth.

Parsons’s position deteriorated when the king agreed to make a number of wide-ranging concessions, including a promise to halt the plantation of Connacht. Parsons succeeded in delaying the passage of the king’s concessions into law by pleading with the king not to give so much away without extracting money from parliament. Many then and since believed that, but for Parsons’s delaying tactics, the king’s concessions would have been passed by the Irish parliament, the catholics would have felt more secure, and the subsequent disaster of 1641 would have been averted.

In February 1642 a royal proclamation arrived in Dublin calling on the rebels to surrender and promising them lenient treatment, after which a number of catholic landowners surrendered voluntarily to the government. Parsons disliked this, and to discourage further submissions, he imprisoned and tortured those who had surrendered and even executed a catholic priest who had saved thirty protestants from being murdered in Athy, Co. Kildare. Similarly, in May he condemned the terms by which the city of Galway had submitted to the government as being too lenient. His actions quickly stemmed the flow of submissions that could have brought a peaceful end to the rising. In the meantime the English Parliament was gaining in power over King Charles I.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography continues:

“Parsons declared an official policy of neutrality while privately favouring parliament in every matter. From October 1642 he allowed two parliamentarian representatives to sit at the meetings of the Irish privy council. However, the royalist Ormond had his supporters in the Irish council. The growing factionalism that pervaded the Dublin administration reflected the mistrust between the royalists and parliamentarians in Ireland.

…Meanwhile in Ireland the catholics organised their own system of government, the ‘catholic confederation’, and were bolstered militarily by the arrival of experienced officers from the Irish regiments serving in the Spanish Netherlands. The protestant forces, starved of pay and munitions, were pushed back once more. The royalists led by Ormond began courting the disgruntled protestant troops in Ireland. In December army officers presented Parsons and his council with a petition outlining their unhappiness at their lack of pay. Although Parsons maintained his grip on the civil administration, the army increasingly looked to Ormond.” This led to his dismissal from the Irish privy council in July and his arrest in August 1643.

Parsons remained a prisoner in Dublin until autumn 1646. By then parliament had won the English civil war and Parsons was released. He died in 1650.

William’s son Richard married Lettice Loftus, daughter of Adam Loftus (1585-1666) of Rathfarnham Castle. Their son William (d. 1658) succeeded as 2nd Baronet of Bellamont. He married Catherine, daughter of Arthur Jones, 2nd Viscount Ranelagh. Their son Richard Parsons (1655-1702) was raised to the title of Viscount Rosse in 1681.

Richard Parsons, 1st Viscount Rosse married three times. He married, firstly, Anne Walsingham, daughter of Thomas Walsingham, on 27 February 1676/77. He was created 1st Viscount Rosse, Co. Wexford [Ireland] on 2 July 1681. He married, secondly, Catherine Brydges, daughter of George Brydges, 6th Baron Chandos of Sudeley on 14 October 1681.

He married his third wife, Elizabeth Hamilton, daughter of Sir George Hamilton, Comte Hamilton in December 1695, after he’d been imprisoned in the Tower of London in February for high treason, according to Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage. I can’t find much information about this.

Viscount Rosse’s father-in-law George Hamilton, Comte Hamilton, was the grandson of the 1st Earl of Abercorn, son of 1st Baronet Hamilton, of Donalong, Co. Tyrone and of Nenagh, Co. Tipperary. George Hamilton travelled to France to fight in the Catholic French army, where he was given the title of Comte, fighting against the British. He married Frances Jenyns, who gave birth to his daughter Elizabeth who married Richard Parsons 1st Viscount Rosse. Frances Jenyns, or Jennings, married a second time, to Richard Talbot, the Duke of Tyrconnell. So we can see the circles in which Richard Parsons mixed, and why it was that he could have been imprisoned for treason.

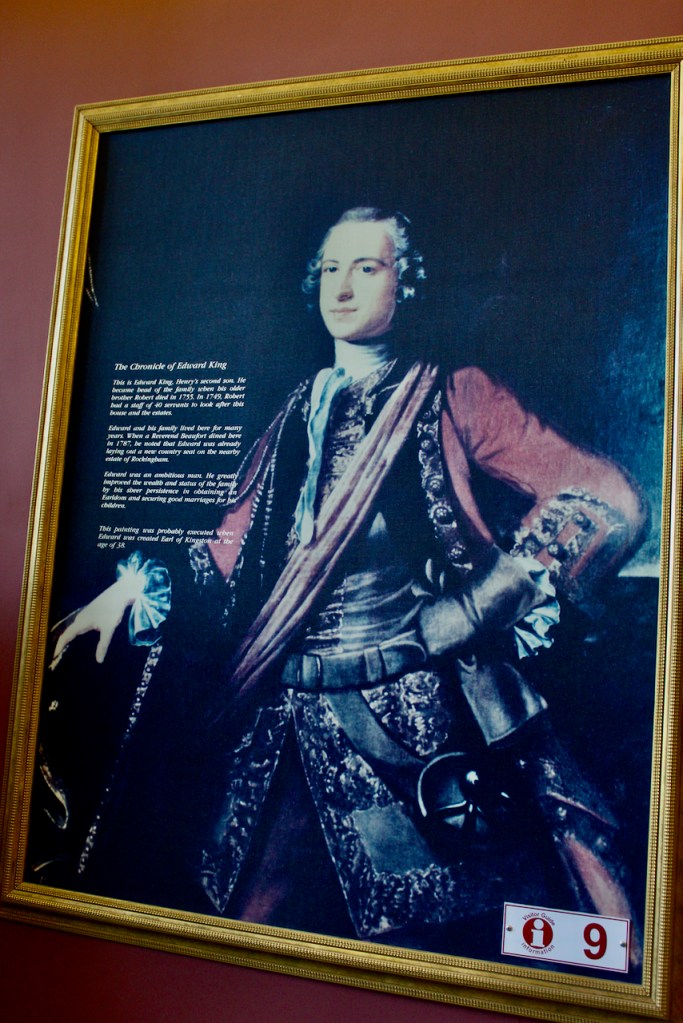

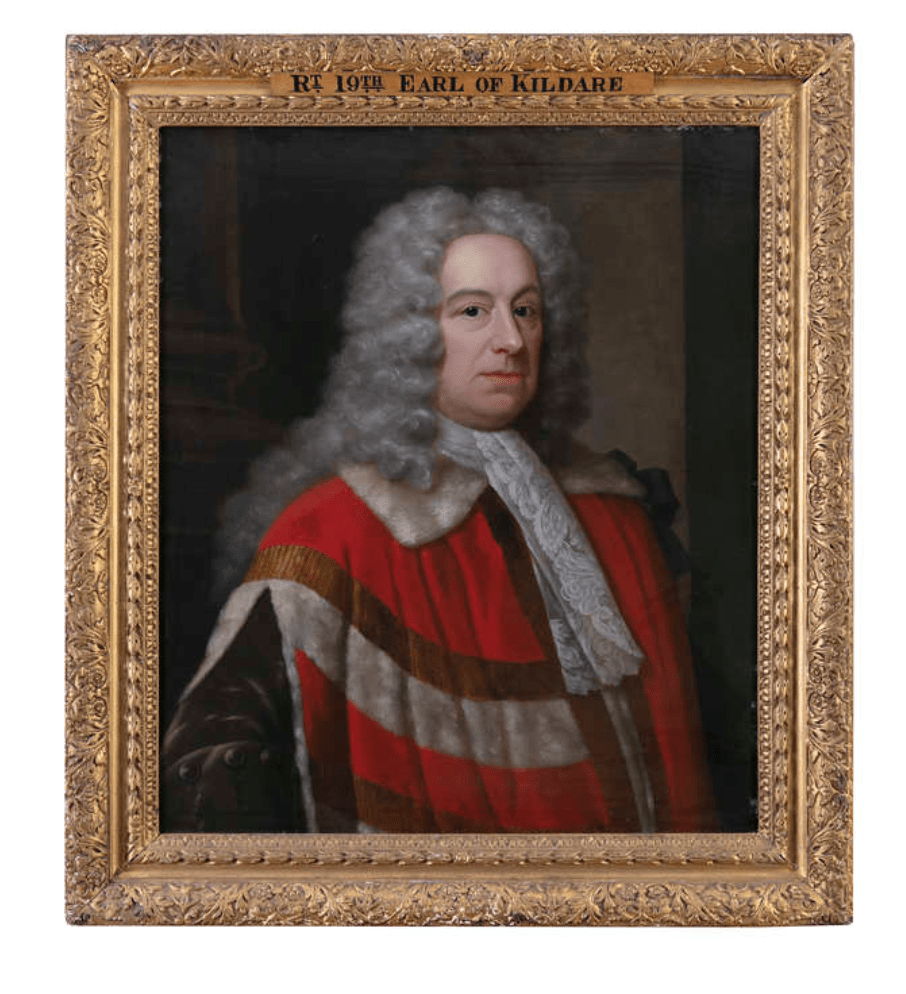

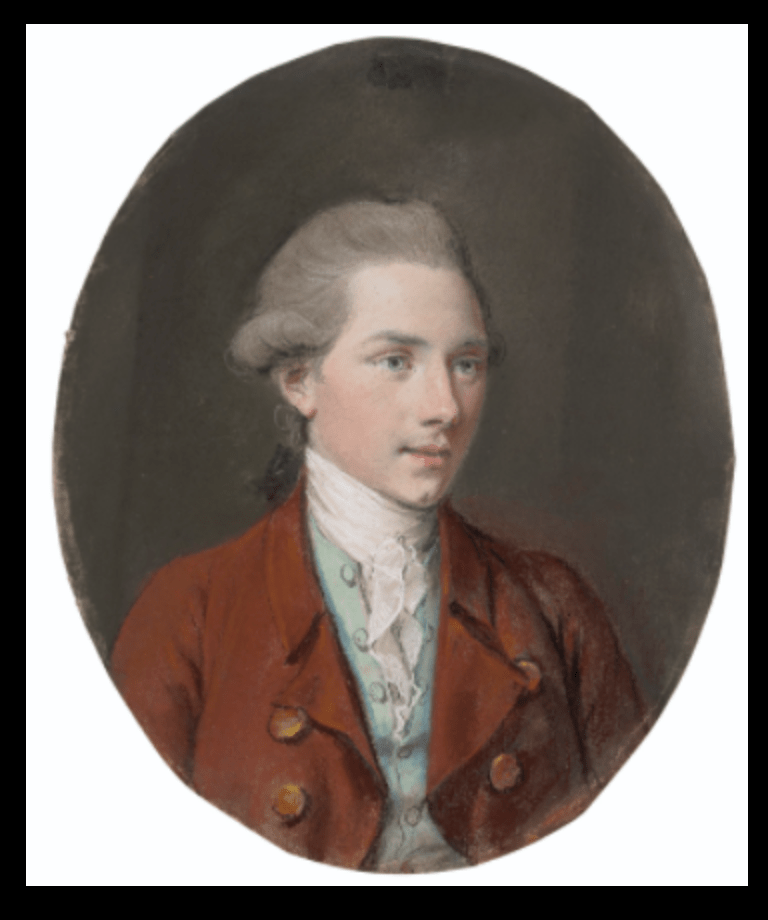

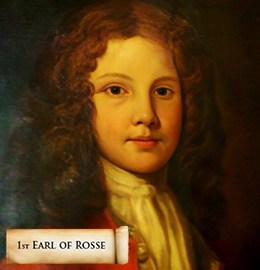

The Viscount must have changed his loyalties, to support William III. The Viscount Rosse’s son by Elizabeth Hamilton, Richard (d. 1741), succeeded as 2nd Viscount Rosse upon his father’s death in 1703. He was raised to the peerage as 1st Earl of Rosse in 1718. He became the Grand Master of the Freemasons and was a founder member of the Hellfire Club which met at Montpelier Hill in a former shooting lodge of William Conolly. The Earl of Rosse’s townhouse on Molesworth Street later became the site of the Masonic Grand Hall. One sees no trace of his supposed Satanic leanings in his portrait in Birr Castle, in which he looks the picture of innocence!

Richard’s son, also named Richard, succeeded as the 2nd Earl but died childless and the title became extinct. It was then created for a second time for the descendants of Lawrence Parsons of Birr Castle.

Let us go back now to the Parson Baronets of Birr Castle. As I mentioned, Laurence Parsons 3rd Baronet of Birr Castle had a son by his first marriage, William (1731–1791). When Laurence died in 1749, William succeeded as 4th Baronet of Birr Castle.

Laurence’s son by his second marriage, Laurence (1749-1807), who inherited his uncle Cutts Harman’s estate County Longford with the proviso that he take the name Harman, became Laurence Harman Parsons. In 1792 he was raised to the Peerage of Ireland as Baron of Oxmantown, in the County of Dublin and in 1795, Viscount Oxmantown. In 1806 when he was created Earl of Rosse in the Irish peerage, of the second creation.

William Parsons (1731-1791) the 4th Baronet served as M.P. and High Sheriff for County Offaly. William in turn was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son Laurence Parsons (1758-1841). When Laurence the 5th Baronet of Birr Castle’s uncle the 1st Earl of Rosse of the second creation died without a male heir, Laurence became the 2nd Earl of Rosse. He married Alice, daughter of John Lloyd Esquire of Gloster, King’s County.

During Heritage Week in 2024, Stephen and I visited Tullynisk house in County Offaly, where Alicia Clement, daughter of the Earl of Rosse, who grew up in Birr Castle, gave a tour of her home. She told us that the Parsons were not as illustrious as the Lloyds, and that Alice Lloyd was considered to be a good catch!

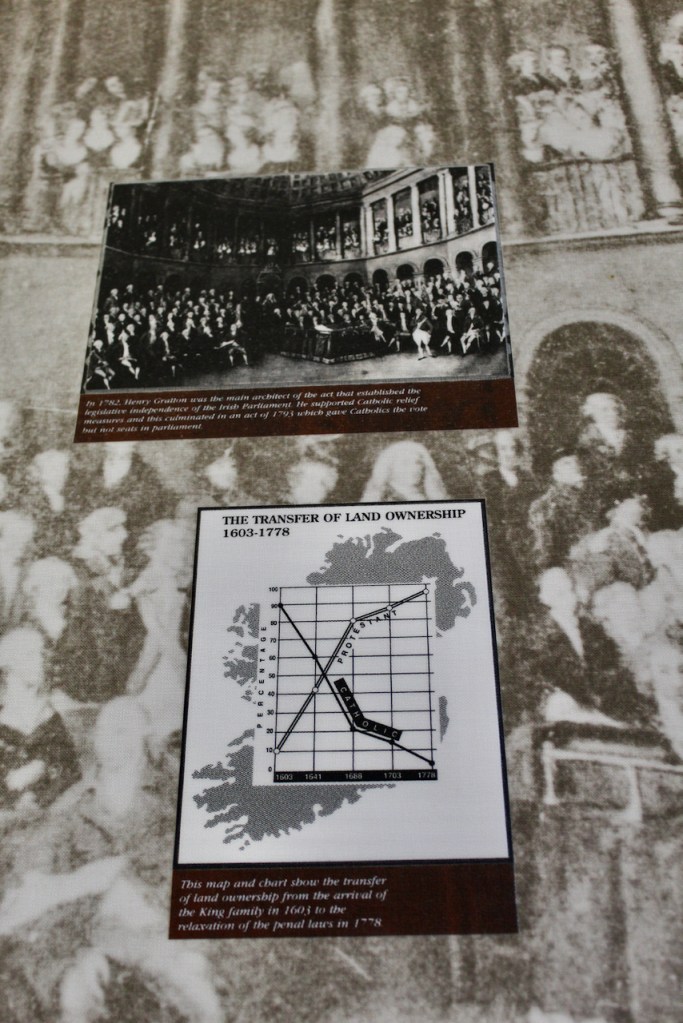

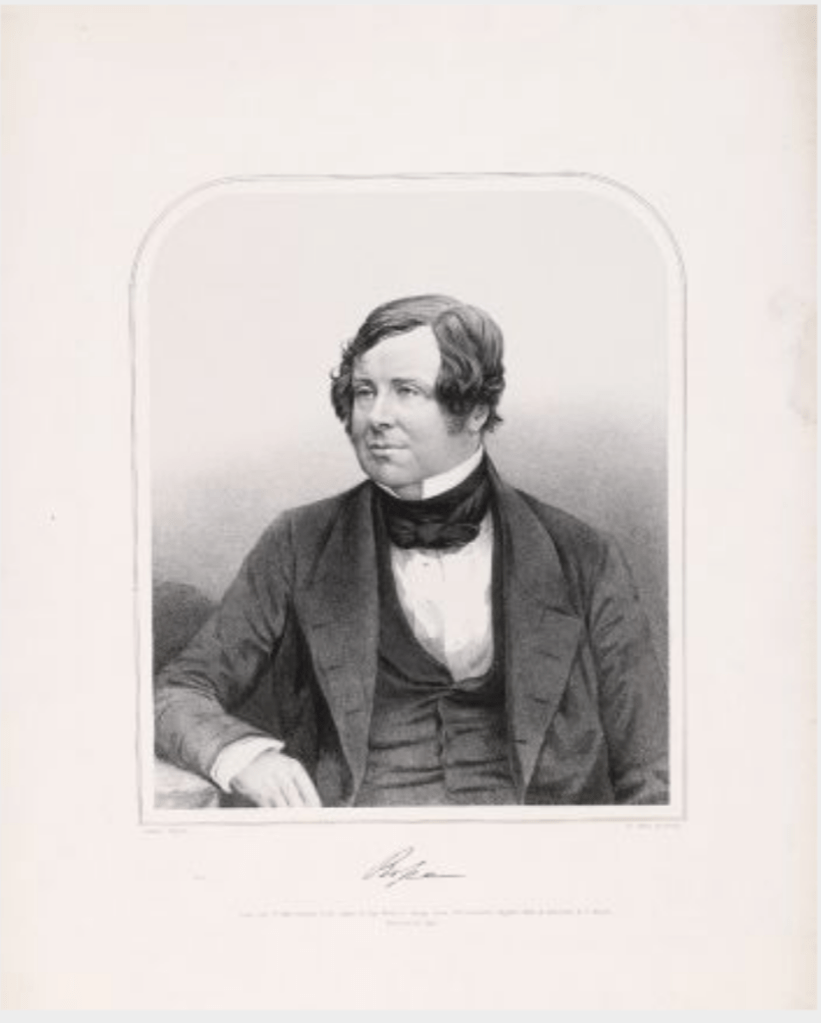

Laurence Parsons (1758-1841) 2nd Earl of Rosse served as M.P. and opposed the Union and the abolishment of the Irish Parliament. He was a friend of Henry Grattan. He was described by Wolfe Tone in his days as an MP as “one of the very few honest men in the Irish House of Commons.” [7]

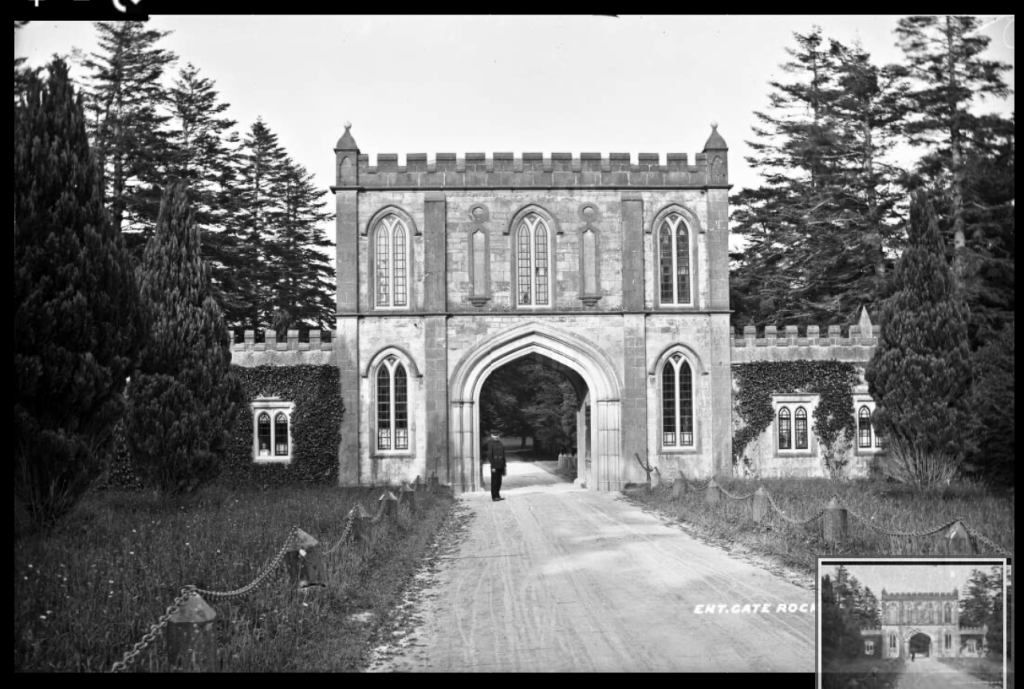

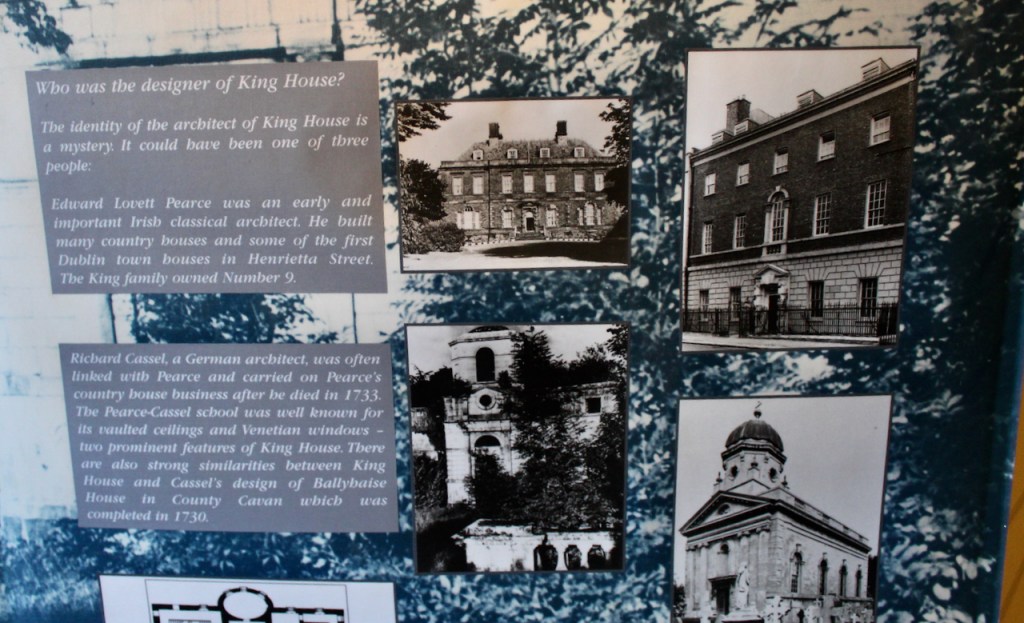

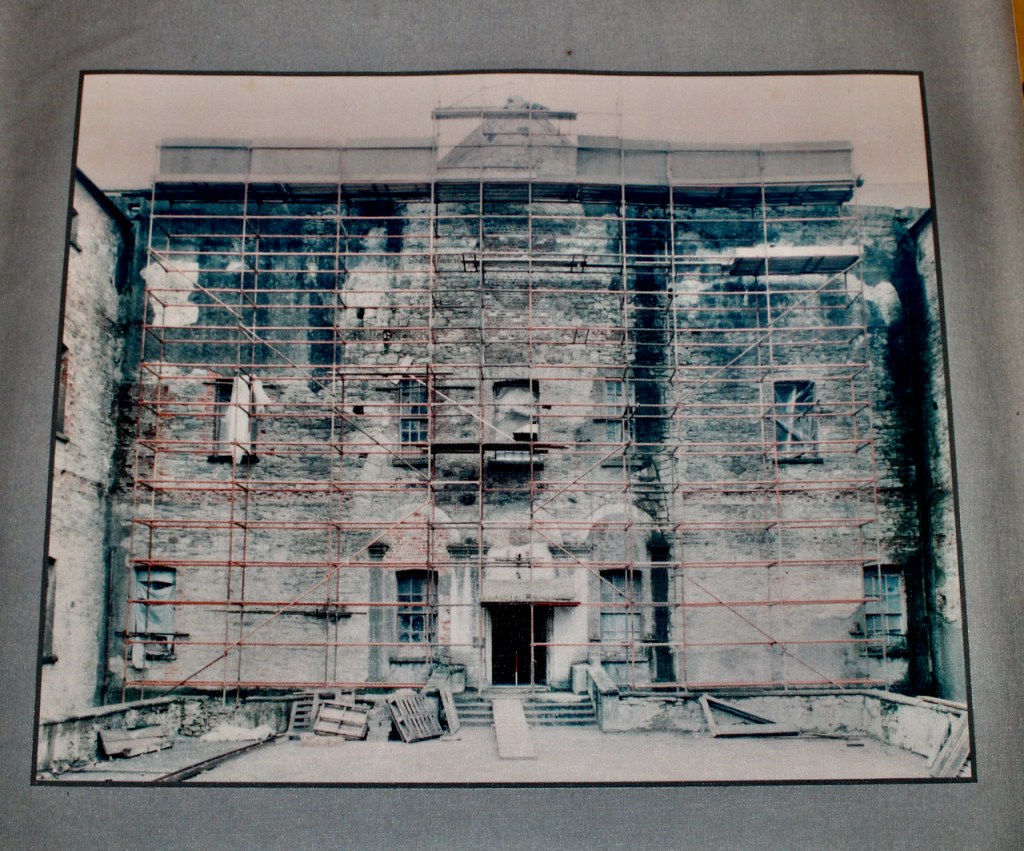

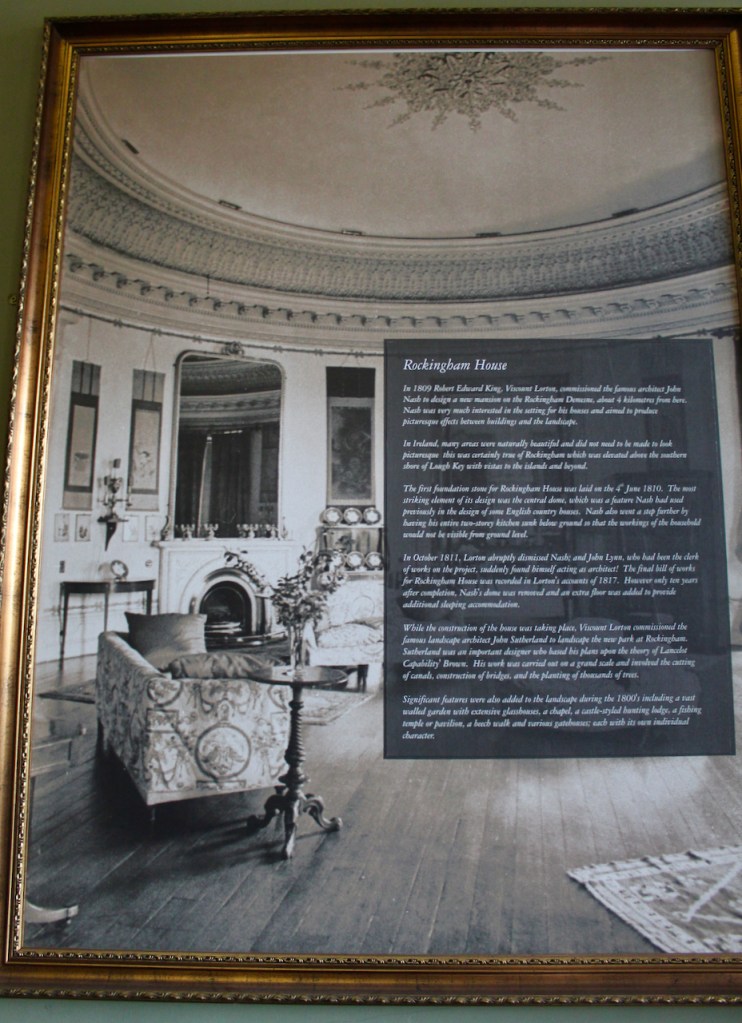

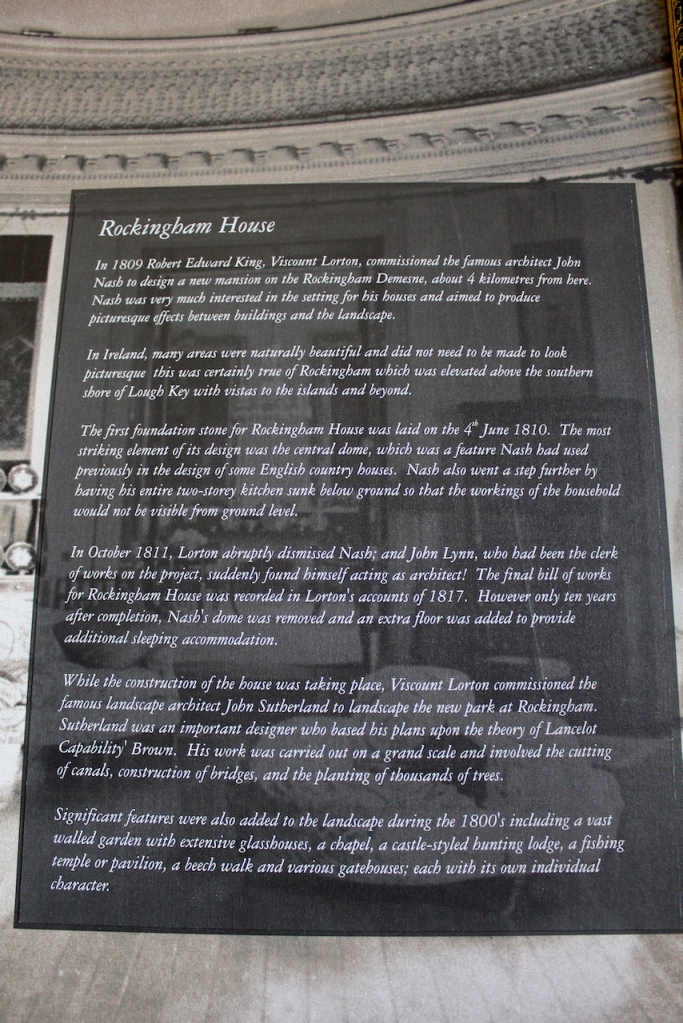

The 2nd Earl of Rosse made further alterations to the castle, shortly after 1800. He worked with a little known architect, John Johnson, and they gave the castle its Georgian Gothic style.

The website explains the additions to the castle:

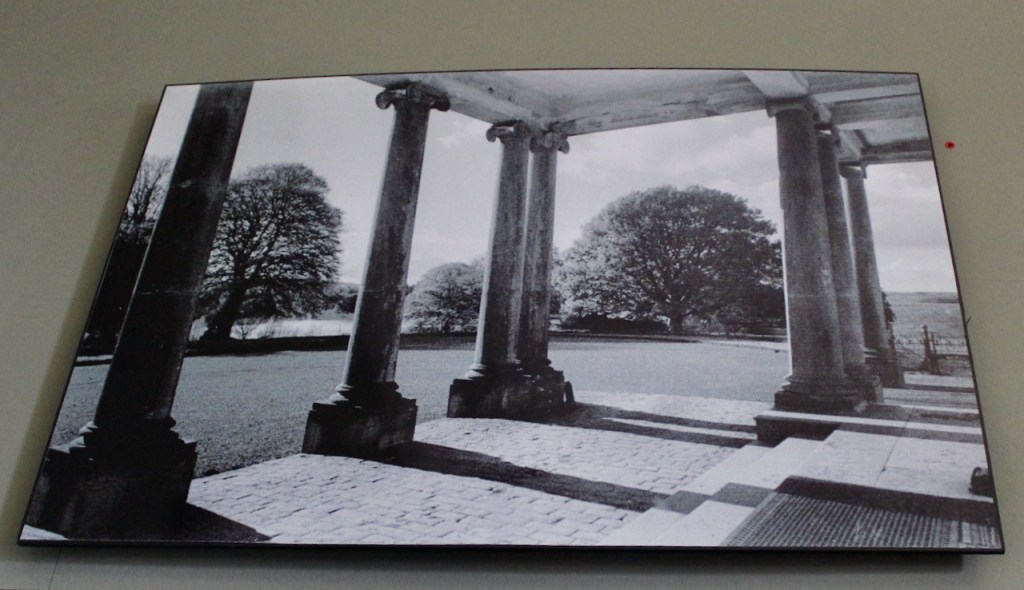

“The castle survived two sieges in the 17th century, leaving the family impoverished at the beginning of the 18th century and little was done to the 17th century house. However, at some time towards the end of that century or at the beginning of the 19th century, the house which had always faced the town, was given a new gothic facade, which now faces the park. The ancient towers and walls on this, now the park side of the castle, were swept away, including the Black Tower (the tower house) of the O’Carrolls, which had stood on the motte. Around 1820 the octagonal Gothic Saloon overlooking the river was cleverly added into the space between the central block and the west flanking tower.”

The entrance we see was previously the back of the house, and most of this facade was added in the additions by the 2nd Earl from 1801 onward. First the two storey porch in the centre of the front, with the giant pointed arch over the entrance door was added and the entire facade faced with ashlar. The third storey which we see was added later, after 1832. The battlements were added as the castle was given a Gothic appearance.

Mark Bence-Jones describes the Castle in his Guide to Irish Country Houses:

“…during the course of C17, the gatehouse was transformed into a dwelling-house, being joined to the two flanking towers, which were originally free-standing, by canted wings; so that it assumed its present shape of a long, narrow building with embracing arms on its principal front, which faces the demesne; its back being turned to the town of Birr and its end rising above the River Camcor. Not much seems to have been done to it during C18, apart from the decoration of some of the rooms and the laying out of the great lawn in front of it, after the old O’Carroll keep and the early C17 office ranges, which formerly stood here, had been swept away ca. 1778. From ca 1801 onwards, Sir Laurence Parsons [1758-1841] (afterwards the 2nd Earl of Rosse), enlarged and remodelled the castle in Gothic, as well as building an impressive Gothic entrance to the demesne. His work on the castle was conservative; being largely limited to facing it in ashlar and giving a unity to its facade which before was doubtless lacking; it kept its original high-pitched roof containing an attic and two C17 towers at either end of the front were not dwarfed by any new towers or turrets; the only new dominant feature being a two storey porch in the centre of the front, with a giant pointed arch over the entrance door. At the end of the castle above the river, 2nd Earl built a single-storey addition on an undercroft, containing a large saloon. He appears to have been largely his own architect in these additions and alterations, helped by a professional named John Johnston (no relation of Francis Johnston). In 1832, after a fire had destroyed the original roof, 2nd Earl added a third storey, with battlements.” [8]

Besides enlarging and remodelling the castle in the Gothic style, the 2nd Earl also built the impressive Gothic entrance to the demesne. [8]

In the book Irish Houses and Gardens, from the archives of Country Life by Sean O’Reilly, the plaster-vaulted saloon which the 2nd Earl added is described: “With the slim lines of its wall shafts and ribs, the free flow of the window tracery and the curious irregular octagon of its plan, the room possesses all the light, airy mood of the best of later Georgian Gothic, and remains one of Birr’s finest interiors.” [9]

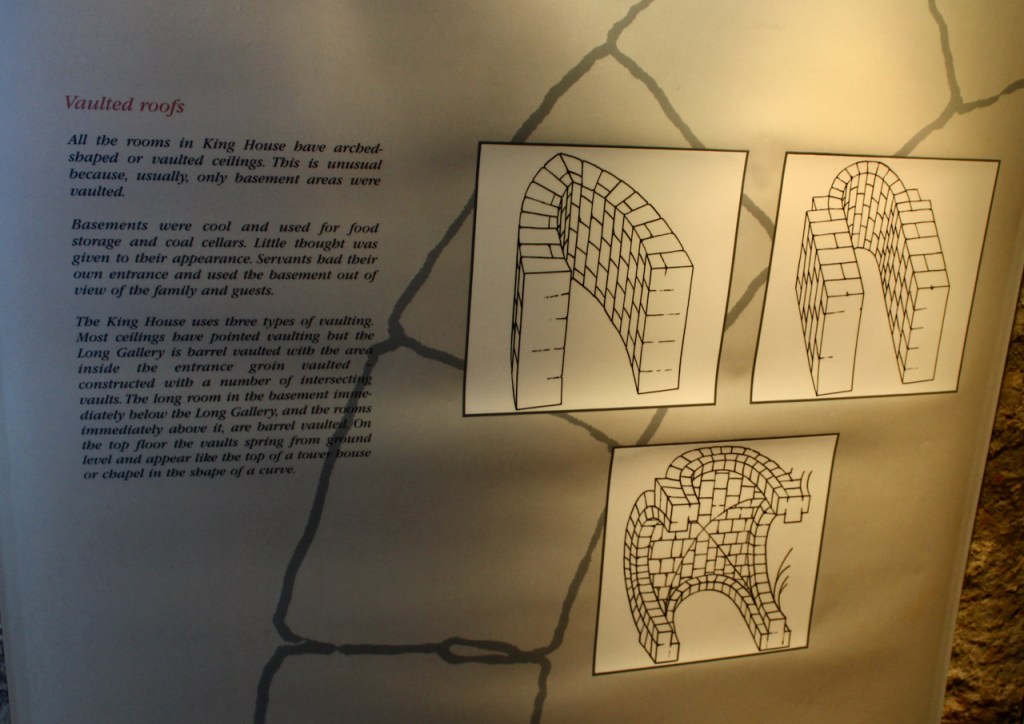

Vaulting fills the castle, even in small hallways.

Laurence Parsons (1758-1841) 2nd Earl of Rosse was succeeded by his son William Parsons (1800-1867), the 6th Baronet and 3rd Earl of Rosse. In 1836 he married Lady Mary, eldest daughter and co-heir of John Wilmer Field Esquire of Heaton Hall, County York. It was this Mary who created the gates which we admired on the way to the Castle.

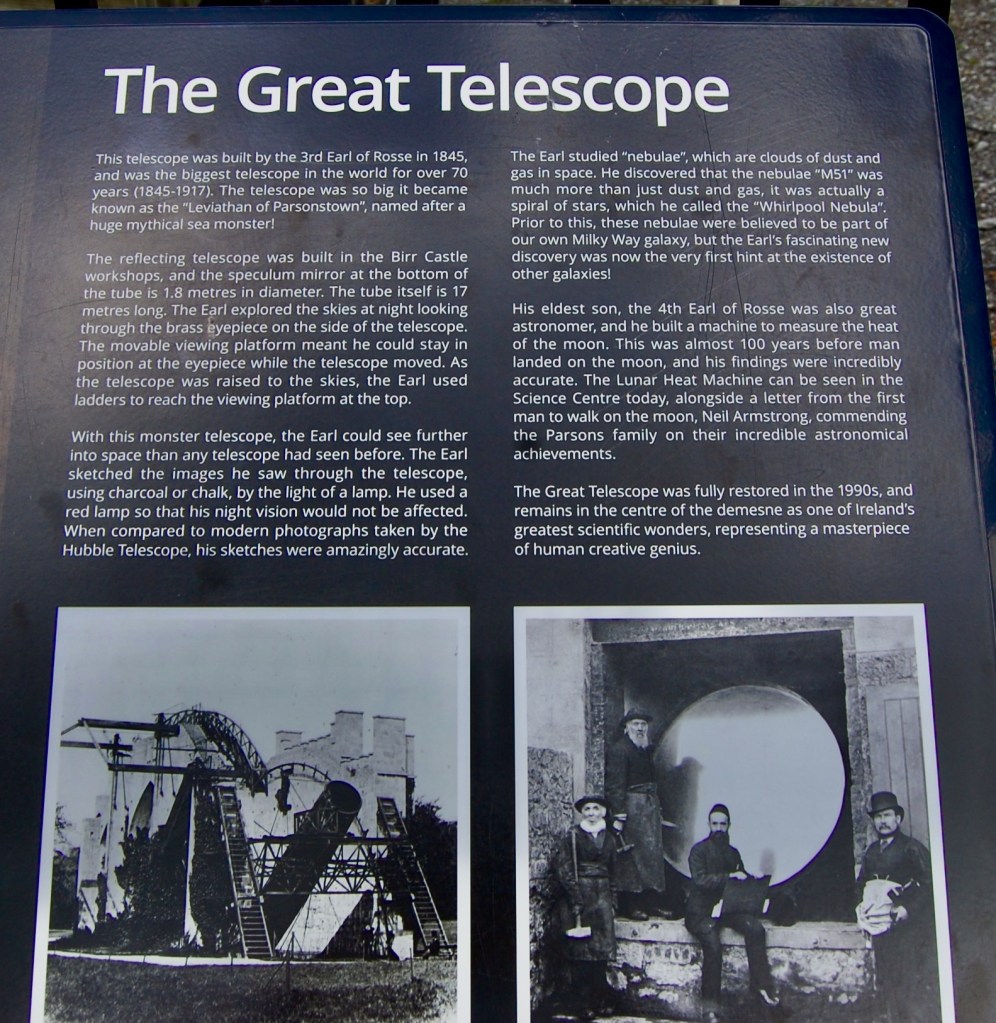

It was the third Earl, William Parsons (1800-1867), who built the world’s largest telescope for over 70 years, in 1845. He was one of the leading scientists and engineers of his day, and he designed the telescope as well as having it built.

All this work took place in rural Parsonstown at the Birr demesne. Furnaces had to be built and local men trained in manufacture and metal casting, overseen by the 3rd Earl. As we saw earlier, his wife Mary also learned metalwork.

Mary was also an accomplished photographer – the photography dark room of his wife Mary née Field has only been rediscovered in the castle recently, but unfortunately we did not get to see it. Their younger son, Charles Parsons, was a groundbreaking engineering pioneer and the inventor of the steam turbine.

The Birr Castle website continues:“After a fire in the central block in 1836 the centre of the castle was rebuilt, ceilings heightened, a third story added and also the great dining room. In the middle of the 1840s to employ a larger work force during the famine, the old moat and the original Norman motte were also flattened and a new star-shaped moat was designed, with a keep gate. This was financed by Mary, Countess of Rosse. This period of remodelling also overlapped with the building of the Great Telescope, The Leviathan.”

Only one person perished in the 1836 fire, a nanny to the children, who is said to haunt the top floor of the house. There’s a crack in the fireplace of the library from this fire, which was started by a cigarette tossed into a bucket of turf.

The website tells us that the final work on the castle was done in the 1860s when a square tower at the back of the castle on the East side was added. This now contains nurseries on the top floor which have a view over the town.

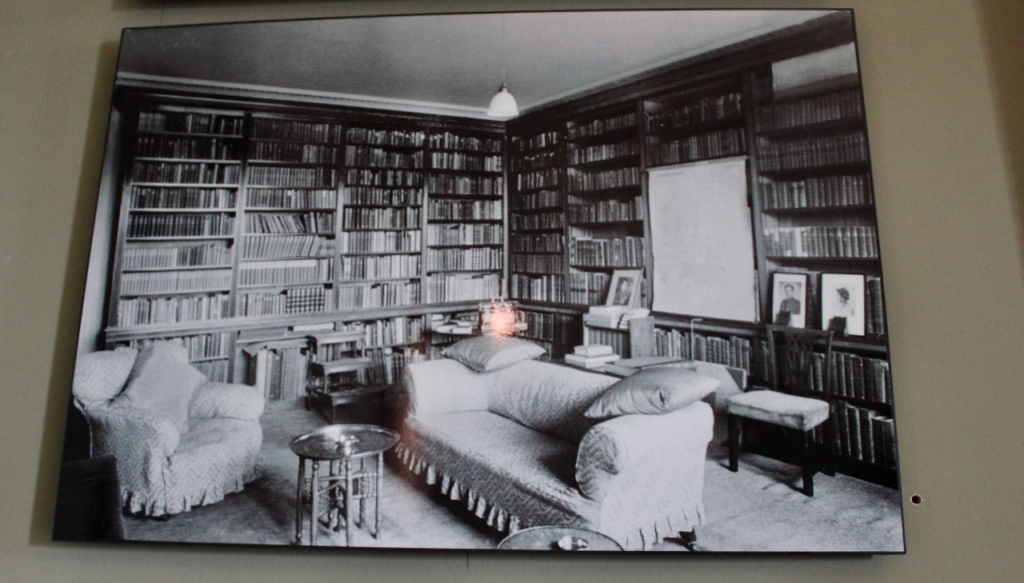

I was overwhelmed by the plush interior of the castle. It was the fanciest I had seen to date. The pelmets are huge, curtains heavy, and paintings old and abundant – although several are copies and not originals, placed due to their relevance to the inhabitants of the castle.

In the front hall there are huge tapestries, brought by the wife of the 6th Earl, Anne Messel, which fit the hall perfectly. The ceiling is sculpted in plaster, as are all of the reception rooms which we visited. There is an enormous wardrobe in the hall which can be taken apart so is called a “travel” wardrobe despite its heft, and a lovely walnut clock stood alongside the walnut exterior wardrobe. It is a Dutch clock, and as well as the time, it tells the date, and the phase of the moon, and has a little clockwork scene that is meant to move on the hour, but is no longer functioning. The clock is “haunted,” the guide told us, and is his favourite piece in the castle. It is said to be haunted because of a few odd incidents that occurred before it was brought to the castle. When someone in the family died, the clock stopped. Another time, at the moment someone in the house died, the pendulum of the clock dropped from its mechanics. Finally, when another person died in the house, the entire clock fell forwards onto its front.

Consequently nobody wanted the clock except the daughter of the family, who brought the clock with her when she moved into Birr Castle. For safety, however, she had the freestanding clock firmly affixed to the wall behind.

The website history of the family tells us:

“The 19th century saw the castle become a great centre of scientific research when William Parsons, 3rd Earl built the great telescope. (See astronomy).His wife, Mary, whose fortune helped him to build the telescope and make many improvements to the castle, was a pioneer photographer and took many photographs in the 1850s. Her dark room – a total time capsule which was preserved in the Castle – has now been exactly relocated in the Science Centre.“

The 3rd Earl was succeeded by his eldest son Lawrence Parsons (1840-1908), 4th Earl of Rosse. He married Frances Cassandra Hawke. He held the office of Chancellor of Dublin University between 1885 and 1908. He was President of Royal Irish Academy (P.R.I.A.) between 1896 and 1901. Also a keen scientist, he constructed a thermometer for guaging the moon’s heat.

He was appointed Knight, Order of St. Patrick in 1890. He held the office of Justice of the Peace (J.P.) for County Tipperary and also for West Riding, Yorkshire, and was Lord-Lieutenant of King’s County between 1892 and 1908.

He was suceeded by his son William Parsons, 5th Earl of Rosse (1873-1918), who in 1905 married Lady Frances Lister-Kaye, daughter of Sir Cecil Lister-Kaye, fourth Baronet of Grange. The 5th Earl served in the military. He was wounded in World War I and later at home in Birr died of his wounds.

The website family history continues:

“Their son the 4th Earl also continued astronomy at the castle and the great telescope was used up to the beginning of the 2nd world war. His son the 5th Earl was interested in agriculture and visited Denmark in search of more modern and successful methods. Sadly he died of wounds in the 1st world war.“

His son Lawrence Michael Harvey Parsons (1906-1979) succeeded as the 6th Earl of Rosse in 1918. In 1935 he married Lady Anne Messel, daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel Leonard Charles Rudolph Messel.

The website continues: “His son, Michael the 6th Earl and his wife Anne created the garden for which Birr is now famous. (see the gardens and trees and plants) Anne, who was the sister of Oliver Messel the stage designer, brought many treasures to Birr from the Messel collection and with her skill in interior decoration and artist’s eye, transformed the castle, giving it the magical beauty that is now apparent to all. Michael was also much involved in the creation of the National Trust in England after the war.“

The Irish Historic Houses website tells us:

“The interior is another skilful combination of dates and styles, forming a remarkably harmonious whole for which Anne Rosse, chatelaine of Birr from the 1930s to the 70s, is chiefly responsible [Anne Messel wife of 6th Earl]. She was the sister of Oliver Messel, the artist and stage-designer, and the mother of Lord Snowdon. A talented designer, decorator and gardener in her own right, her arrangement of the family collections is masterly.” [see 2]

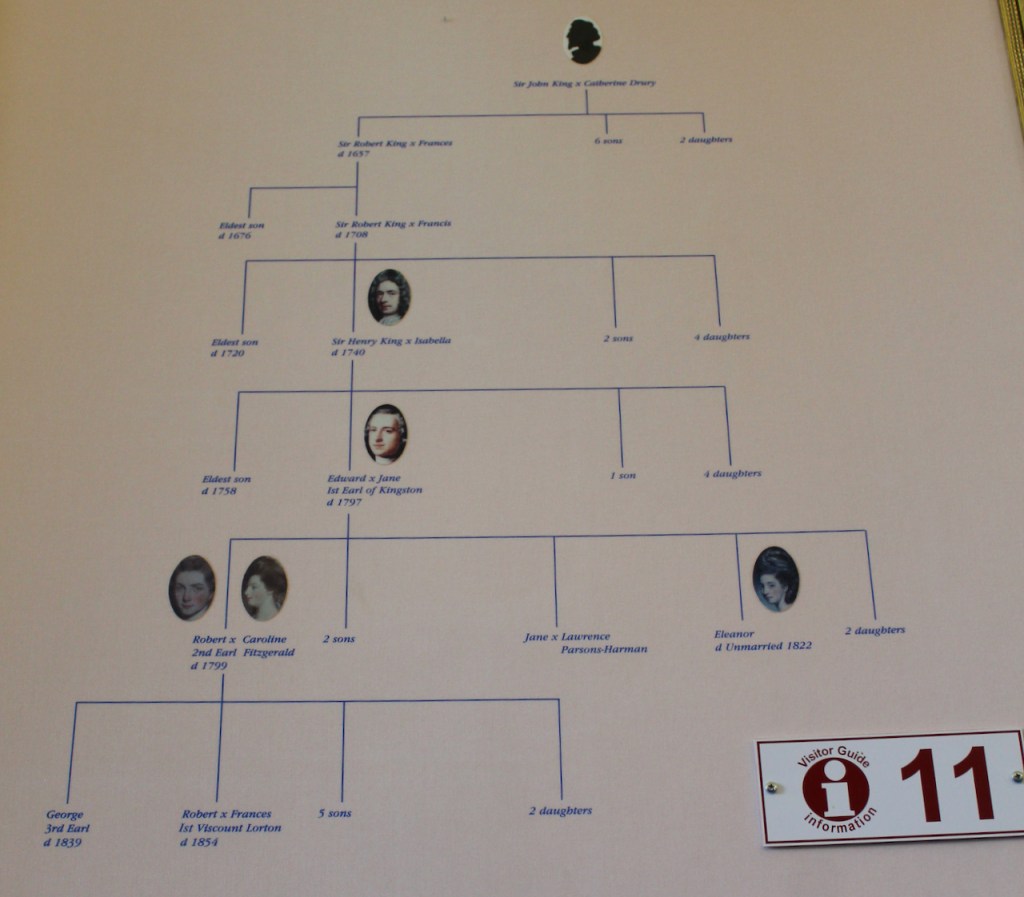

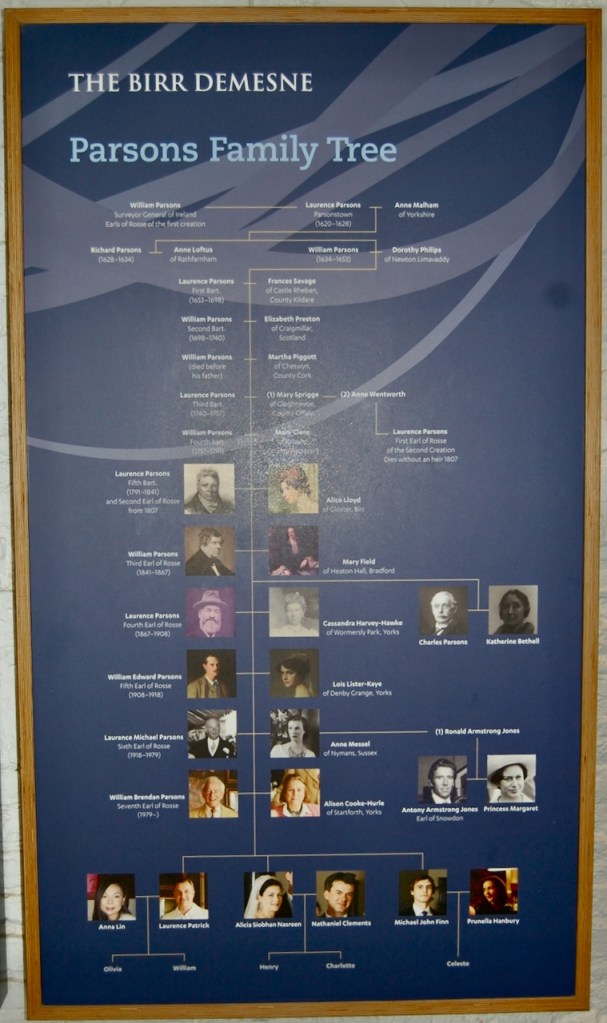

Anthony Armstrong-Jones, who married Princess Margaret, is a son from Anne Messel’s first marriage, her second marriage being to the sixth Earl of Rosse, Laurence Michael Parsons. The museum, off the Ticket Office, has a family tree:

A sister of Anthony Armstrong-Jones married into the Vesey family of Abbeyleix, who owned the De Vesci estate. My father grew up in Abbeyleix. We used to be able to walk in the grounds of the De Vesci estate but it has since been closed to the public.

The website continues to tell us of the next generation: “Their son Brendan, the present Earl [b. 1936, he succeeded his father as the 7th Earl of Rosse in 1979], spent his career in the United Nations Development Programme, living with his wife Alison and their family in many third world countries. He returned to Ireland on his father’s death in 1979. Brendan and Alison have also spent much time on the garden, especially collecting and planting rare trees. Their three children are all passionate about Birr and continue to add layers to the story for the future.

“Patrick, Lord Oxmantown currently lives in London and is working on plans to bring large scale investment into Birr which will enable him and his family to move back to Ireland.

“Alicia Clements managers the Birr Castle Estate and lives in the sibling house of Tullanisk.

“Michael Parsons, works in London managing a portfolio of properties for the National Trust and is a board member to The Birr Scientific and Heritage Foundation.”

After our castle tour, we ate our lunch under a tree on a lovely circular bench made of a huge tree trunk, then went to see the telescope.

The telescope contains a speculum mirror at the bottom of the tube, which is 1.8 metres in diameter. The mirrors were made in a workshop set up by William Parsons, and the speculum had to be taken away and polished up every once in a while, so a second speculum mirror was made. The tube which houses the speculum is 17 metres long and was made near me in the Liberties, in a Foundry on Cork Street. The Earl would look into the telescope via a brass eyepiece in the enormous wooden tube, by climbing up the stairs on the side of the stone walls, to the viewing platform. With the telescope, the Earl could see further into space than anyone had ever seen. He sketched what he saw. According to the information at the site, his sketches were amazingly accurate when compared to modern photographs taken by the Hubble Telescope. The Earl studied “nebulae,” which are clouds of dust and gas in space, and discovered the “Whirlpool Nebulae.” There is now a planting of trees in the grounds of the castle to honour the founding of this M51 nebula. The “whirlpool spiral” of trees is a plantation of lime trees, planted in 1995, marking 150 years since the Earl discovered the nebula.

The sixth Earl of Rosse, Lawrence Michael Harvey Parsons, pursued an interest in trees and botany rather than the stars and moon, and created the gardens. We enjoyed the beautifully sunny day, walking around the generous landscape.

The spring wildflower meadow has not been ploughed since at least 1620. Grass is let grow long to allow wildflowers, bees and wildlife to flourish.

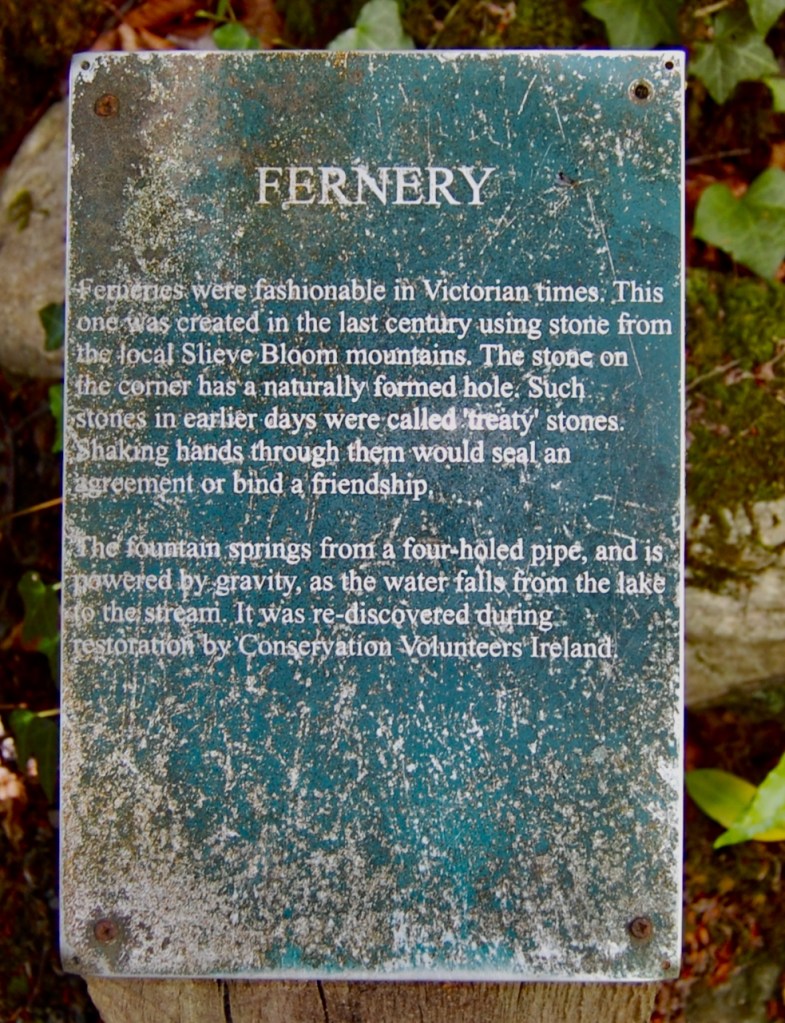

We entered The Fernery, which according to the sign beside it, tells that Ferneries were fashionable in Victorian times.

This little fountain works by gravity, as the water falls from the lake to the stream. It’s an aspect I love about exploring heritage properties: the clever and sustainable engineering of the times. We have much to learn from our ancestors. I love that they have kitchen gardens and walled gardens and were self-sustaining.

The Brick Bridge, formerly called the Ivy Bridge, is in County Tipperary, according to our leaflet about the grounds of Birr Castle.

Above, the Teatro Verde, “Green Theatre,” from which you can see the vista of the castle and demesne. It was inspired by the design of 18th century architect and family member Samuel Chearnley. Dedication to Edward and Caroline on a plaque on the bench, “In Truth we Love, in Love we Grow.”

We didn’t have the energy to explore the entire garden, but followed the map to see a few places such as the Fernery, the Teatro Verde, and the Formal Gardens. Along the way, we passed the box hedges, the tallest in the world! The box hedges are around ten metres tall, and are over 300 years old.

The Formal Gardens were designed by Anne Messel, the 6th Countess of Rosse, to celebrate her marriage to the 6th Earl, Michael, in 1935. There are white seats either end which bear their initials, which she designed. The hornbeam arches are in the form of a cloister complete with “windows”!

We headed back to the visitor centre and museum, passing the children’s area, the wonderful Tree House! The current owners, Brendan Parsons, who was director of the Irish House and Gardens Association for eleven years, and his wife Alison, have been leading advocates for finding a new role for country houses in a heritage and educational context.

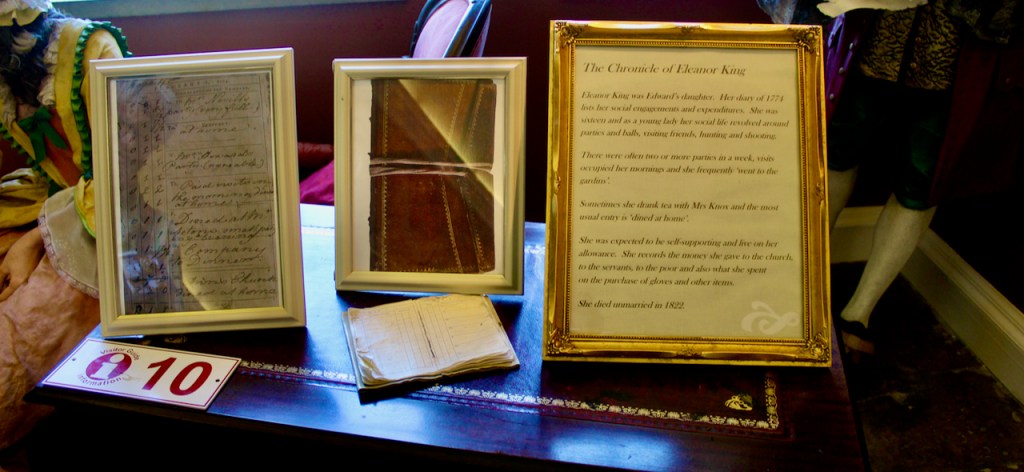

In the museum, we studied the pictures and explanations, but had to ask where it was that the viewer would sit or stand to look through the telescope. There’s a great timeline in the museum – I always find these very useful and informative!

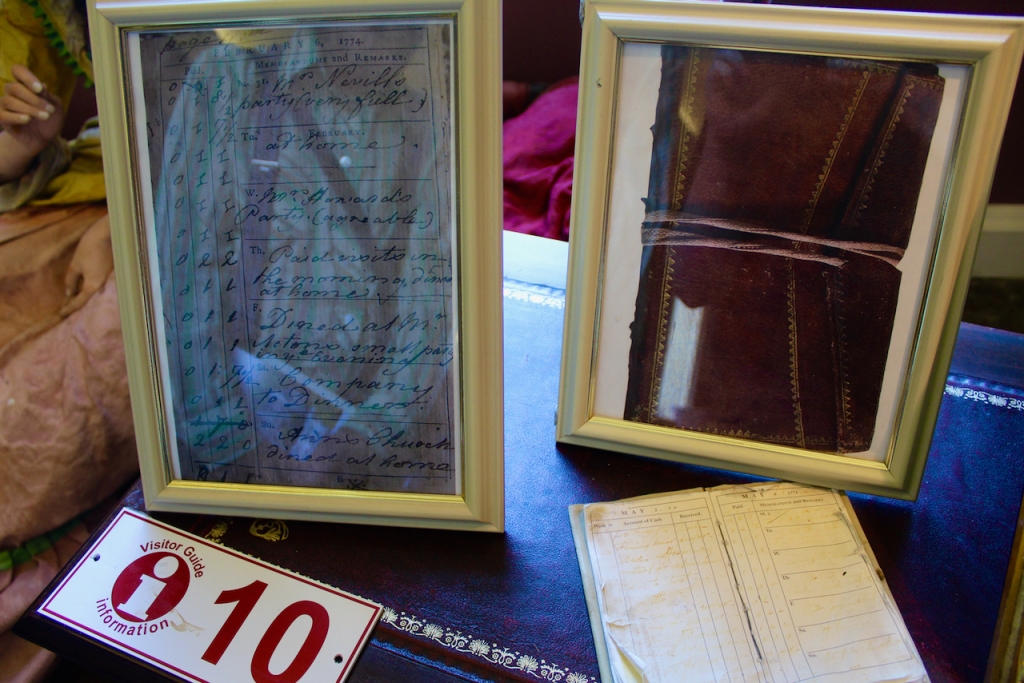

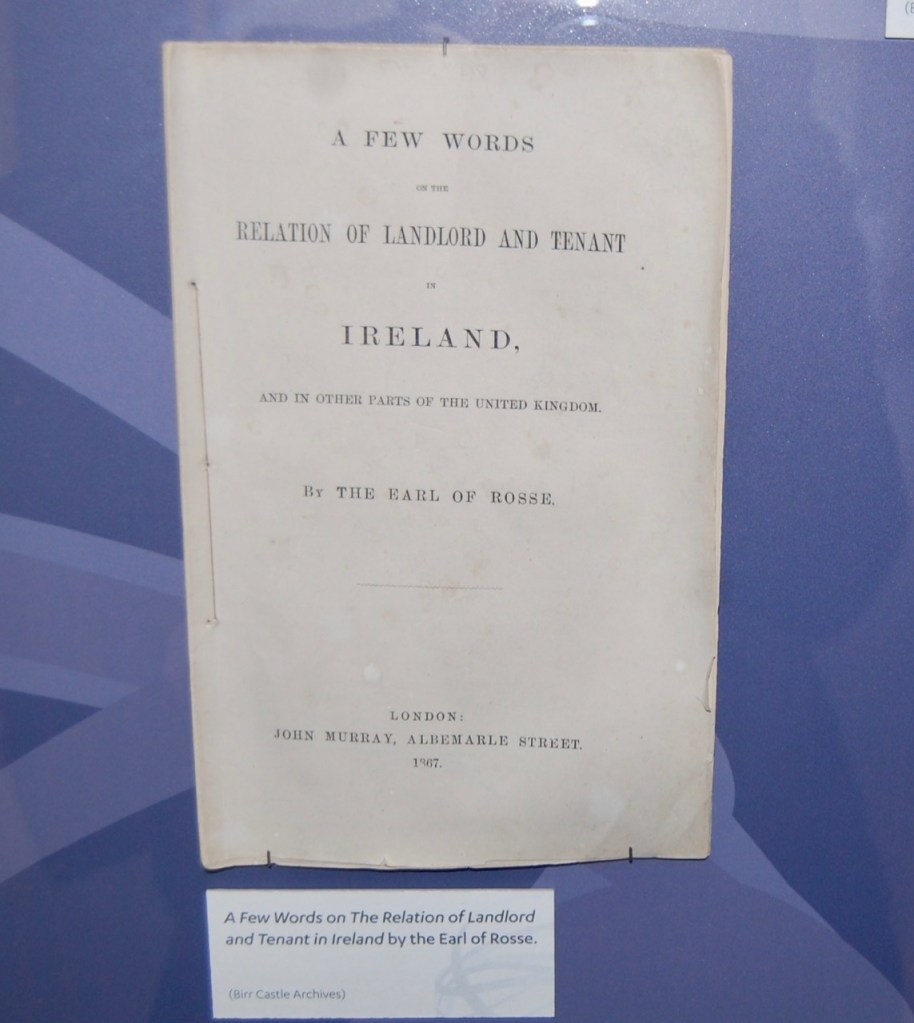

It was interesting also to see some documents from the family archives, including a booklet written by the Earl about management of property, and purchase of the elements that make up the speculum mirror, which is made of metal and not glass – only later did they make mirrors of glass for telescopes.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] http://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Birr%20Castle

[3] During the period 1979-2007, Lord and Lady Rosse facilitated research by Dr. Anthony Malcomson, former director of the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), and latterly sponsored by the Irish Manuscripts Commission, to enable the production of a comprehensive calendar of the Rosse Papers in 2008. The archive is held in the Muniment Room of Birr Castle.

[4] p. 12, Robertson, Nora. Crowned Harp, Memories of the Last Years of the Crown in Ireland, published 1960 by Allen Figgis & Co. Ltd., Dublin.

[5] https://www.tcd.ie/media/tcd/mecheng/pdfs/The_Family_Parsons_of_Parsonstown.pdf

[6] https://birrcastle.com/sharing-our-heritage/

[7] Hugh Montgomery Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes. Great Houses of Ireland. Laurence King Publishing, London, 1999.

[8] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[9] O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens, from the archives of Country Life, Aurum Press, London: 1998, paperback edition 2008.

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €11 for the A5 size, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My website costs €300 per year on WordPress.

€15.00

Donation towards website

I receive no funding nor aid to create and maintain this website, it is a labour of love. The website hosting costs €300 annually. A generous donation would help to maintain the website.

€150.00