www.slieile.ie

Open dates in 2025: Apr 5- Oct 12, Sat-Sun, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24, 2pm-6pm

Free

2025 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2025 Diary of Historic Houses (opening times and days are not listed so the calendar is for use for recording appointments and not as a reference for opening times) send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €10 for the A5 size calendar, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

A house was first built at Burton Park around 1665 for John Perceval (1629–1665), 1st Baronet. However, this was destroyed and a later house built on its footprint. The house, which was not completed until 1709, was three times the size of the present building, which was remodelled in the late 1800s.

The house has been in the ownership of only two families: the Percevals and the Purcells. It now houses Slí Eile, and the website tells us:

“In the Irish language, slí eile means ‘another way’ and Slí Eile was set up to provide an alternative recovery option for those who might otherwise have to spend time in psychiatric hospital…People who come to Slí Eile spend a period of 6-18 months in a residential community in which support is available from both professional staff and from peers. Participating in the Slí Eile community provides an opportunity for a fresh start in a safe, nurturing environment. It also serves to restore a structured pattern to life. It helps in the development of both interpersonal skills and the practical skills that are required for daily living.” [1]

You can read more about Slí Eile on their website.

The website tells us that the original dwelling was fortified with high walls around the house, with four turrets, one at each corner. There are a number of underground passages, recently discovered, which correspond with the sites of the turrets as they would have appeared in the original design.

Philip Perceval (1605-1647), father of John, came to Ireland where he served as registrar of the Irish court of wards, along with his brother Walter. When Walter died in 1624, Philip inherited the family estates in England and Ireland. The land at Burton Park was named after his estate in Somerset, Burton. He settled in Ireland, and by means of his interest at court he gradually obtained a large number of additional offices. In 1625 he was made keeper of the records in the Birmingham Tower at Dublin Castle.

Perceval was close to the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford. With the fall and execution of Wentworth in May 1641, Perceval lost his major patron and protector. In September 1641 Perceval narrowly avoided prosecution in England when his part in a shady land transaction was revealed. By that time, Perceval owned over 100,000 acres in Ireland, which he obtained partly through forfeited lands.

Philip Perceval married Catherine Ussher, daughter of Arthur Ussher and Judith Newcomen. She gave birth to their heir, John (1629–1665), who was created 1st Baronet in 1661. A younger son, George (1635-1675) lived at Temple House in County Sligo, another Section 482 property which we have yet to visit.

In 1665 the officer-architect Captain William Kenn, then engaged on Charleville Manor for Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery, proposed a design, and building work on Burton Park started for the 1st Baronet Perceval. [2]

John Perceval served in Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth. He was involved in sending the opponents of Cromwell from their sequestered lands to Connaught. However, he began to distance himself from the Parliament and declined Cromwell’s invitation to sit in Cromwell’s Parliament.

After the Restoration of King Charles II, John Perceval was pardoned for his part in Cromwell’s government, and was granted a Baronetcy (of Kanturk) and made a Privy Councillor to Charles II. He married Catherine Southwell of Kinsale, County Cork.

Catherine and John’s son eldest son and heir died at the age of 24 and he was succeeded by his brother, John (c. 1660-1686), who became 3rd Baronet of Kanturk.

John the 3rd Baronet married Catherine Dering, daughter of Edward 2nd Baronet Dering, of Surrenden Dering, Co. Kent. Their son Edward became 4th Baronet at the age of just four years old but he died aged 9. The next son, John, succeeded as 5th Baronet in 1691 on the death of his brother, and in 1733 was created 1st Earl of Egmont.

In 1690 Burton Park house was burnt by Duke of Berwick’s Jacobite forces as they retreated south after the Battle of the Boyne. The Duke of Berwick, James Fitzjames, was the illegitimate son of King James II. The village of Churchtown and fifty other big houses were destroyed.

The 1st Earl of Egmont rebuilt the house. Frank Keohane writes:

“After being burnt, the house’s rebuilding was delayed by a second long minority until the first decade of C18. The stables were commenced first, and unknown Italian architect was recorded at work in 1707 by the steward. [fn. A proto-Palladian plan dated 1709 shows a colonnaded hall and a portico before the door. Its designer was perhaps James Gibbs, whom Perceval had befriended in Italy when Gibbs was a student of Carlo Fontana.] In 1710 Rudolph Corneille, a Huguenot military engineer, proposed to rebuild the house for £2000. William Kidwell was paid for a chimneypiece in 1712. The house does not appear to have been completed, however, and the demesne was leased in 1716. A drawing of 1737 records the house standing as a shell, while in 1750 Smith described the ruin as ‘a large elegant building, mostly of hewn stone.’ ” [3]

Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe writes in Voices from the Great Houses: Cork and Kerry that Perceval is believed to have commissioned Italian architects to submit designs for a new house in 1703, incorporating many Palladian features, to be built on the foundations of the original house. She writes that the mansion was completed in 1709 and was remodelled in the late nineteenth century. [4]

The Percevals didn’t live in Ireland, however, as they served as politicians in the British government.

John Perceval the 1st Earl was elected for the British parliament to represent Harwich in England from 1728 to 1734. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us “He was a regular attender at court, and sat (1727–34) for Harwich in the British house of commons, where he had some success in promoting trade concessions for Ireland. Other interests included prison conditions and the Georgia colony [in the United States], of which he was a co-founder in 1732.“

It’s fascinating that he was a founder of Georgia in the United States! He supported James Oglethorpe’s scheme to establish a new colony. He was acquainted with Oglethorpe from their work on the Gaols Committee of the House of Commons, which was painted by William Hogarth. The National Portrait Gallery of London tells us he played a crucial role in securing the funding that was essential for the support and defence of Georgia.

Oglethorpe gained a reputation as the champion of the oppressed. He pressed for the elimination of English prison abuses and, in 1732, defended the North American colonies’ right to trade freely with Britain and the other colonies. [5] The prison reforms Oglethorpe had championed inspired him to propose a charity colony in America. On June 9, 1732, the crown granted a charter to the Trustees for Establishing the Colony of Georgia. Oglethorpe himself led the first group of 114 colonists on the frigate Anne, landing at the site of today’s Savannah on February 1, 1733. The original charter banned slavery and granted religious freedom, leading to the foundation of a Jewish community in Savannah.

In 1742, Oglethorpe called upon his military experience and Georgia’s fledgling militia to defend the colony from a Spanish invasion on St. Simons Island. Oglethorpe and his militia defeated the invaders in the Battle of Bloody Marsh, which is credited as the turning point between England and Spain’s fight for control of southeastern North America. [5]

John Perceval was a friend of Bishop George Berkeley, Church of Ireland Bishop of Cloyne. The philosopher-bishop was chaplain to John Perceval and tutor to his son. Papers relating to Burton House tell us that during his stay at Burton, Berkeley enjoyed long walks through its wooded demesne and may have slept on a hammock strung in the barn!

Extracts from the correspondence between Berkeley and Perceval (Ryan-Purcell papers) reveal the special affection the bishop reserved for Burton:

“Trinity College, 17th May 1712:

… Burton I find pleases beyond expectation; and I imagine it myself at this time one of the finest places in the world …

“Trinity College, 5th June 1712: Dan Dering (Perceval’s cousin) and I deign to visit your Paradise, and are sure of finding angels there, notwithstanding what you say of their vanity. In plain English, we are agreed to go down to Burton together and rejoice with the good company there. I give you timely warning that you may hang up two hammocks in the barn against our coming. I never lie in a feather bed in the college and before now have made a very comfortable shift with a hammock.

“London, 27th August 1713:

Last night I came hither from Oxford. I could not without some regret leave a place which I had found so entertaining, on account of the pleasant situation, healthy air, magnificent buildings, and good company, all which I enjoyed the last fortnight of my being there with much better relish than I had

done before, the weather having been during that time very fair, without which I find nothing can be agreeable to me. But the far greater affliction that I sustained about this time twelvemonth in leaving Burton made this seem a small misfortune …” [6]

John Perceval’s son John Perceval (1711–70), sat for Dingle in the Irish commons from 1731 to 1748, when he succeeded to his father’s peerage after his father’s death and became 2nd Earl of Egmont. He was a member of the British Commons, 1741–62, and was a close adviser to Frederick, Prince of Wales. [6]

John 2nd Earl’s sister Helena married John Rawdon, 1st Earl of Moira.

John 2nd Earl married Catherine, daughter of James Cecil 5th Earl of Salisbury. She gave birth to the next in line, John James Perceval (1738-1822) 3rd Earl of Egmont, along with several other children.

When she died, John the 2nd Earl remarried, this time to Catherine Compton, granddaughter of the 4th Earl of Northampton in England. They had several more children.

From 1751-1759 the 2nd Earl created a house in England, Enmore Castle. He served as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1763-1766 and a port in the Falkland Islands, Port Egmont, was named after him, as well as Mount Egmont in New Zealand.

The 2nd Earl of Egmont was created Baron Lovel and Holland of Enmore, Co. Somerset in 1762, which gave him an automatic seat in the House of Lords.

Following his death, his widow was created Baroness Arden of Lohort Castle, County Cork in the peerage of Ireland, with remainder to her heirs male. This gave the oldest son of his second wife a title.

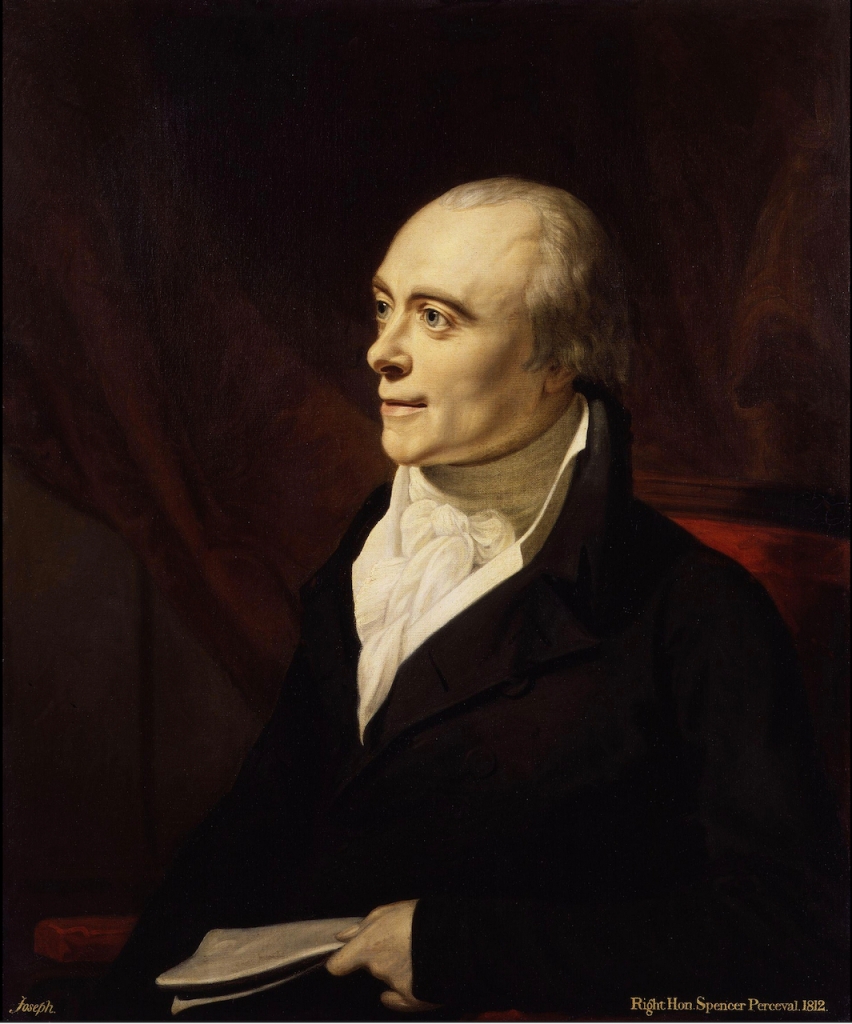

His third son, Spencer Perceval (1762–1812), became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and is the only British prime minister to have been assassinated, and the only solicitor-general or attorney-general to have become prime minister.

A son of the first marriage, John James Perceval (1737-1822) became 3rd Earl of Egmont when his father died in 1770, as well as 2nd Baron Lovel and Holland of Enmore, Co. Somerset. He also entered politics in England and served in the British House of Lords.

He did not live at Burton Park and in 1800 he rented it to John Purcell, a member of the family of the Barons of Loughmoe (see my entry on Ballysallagh, County Kilkenny, for more of this branch of the family). He rented the property for his newly married eldest son, Matthew (1773-1845), Rector of Churchtown (1795-1845) and of Dungourney (1808-45).

John James Perceval the 3rd Earl Egmont married Isabella Powlett, granddaughter of the 2nd Duke of Bolton, and they had a son, John (1767-1835) who became 3rd Baron Lovel and Holland, of Enmore, County Somerset and 4th Earl of Egmont. The 4th Earl of Egmont followed in his father’s footsteps and served in the House of Lords. He married Bridget Wynn, daughter of an MP for Caernarvon in Wales and they had a son, Henry Frederick John James Perceval (1796-1841) who became 5th Earl of Egmont after his father’s death, as well as 4th Baron Lovel and Holland of Enmore, Co. Somerset.

The 5th Earl of Egmont inherited large debts. The History of Parliament website tells us:

“Debts of some £300,000 had accumulated on the estate at Churchtown, county Cork, and the property at Enmore, Somerset, was also heavily encumbered. The barrister engaged to defend Perceval’s will claimed that he was ‘a man of education and refinement’ whose ‘feeling of disappointment … on account of the enormous embarrassments on his property, led him to drink, and at an early period of his life he acquired habits of dissipation’; the opposing counsel blamed this fall from grace on neglect by his mother, who was portrayed as a scheming courtesan.” [7]

The Parliament website continues the sorry tale:

“Having thus compounded his financial difficulties, Perceval was declared an outlaw at some point in 1828 and fled abroad. Later that year he married the daughter of a French count in Paris, but evidently not under the auspices of the British consulate. The son born to them about four months after the marriage was apparently living in 1835, but predeceased his father; the fate of the mother has not been discovered. On his father’s death in 1835 Perceval inherited all his property, but the will was not proved until 1857, when the personalty was sworn under £16,000. Enmore had been sold in 1834 for £134,000 to pay off creditors, but no takers had been found for the Cork estates, which comprised 11,250 acres, because of the burden of debt on them. Egmont took his seat in the Lords in February 1836, but afterwards lived under the alias of ‘Mr. Lovell’ at Burderop Park, Wiltshire. This property was purchased in the name of his companion, a Mrs. Cleese, with whom it seems he had previously resided at Hythe, Kent and whom he passed off as his sister.” [7]

The website tells us the nature of his regular pursuits can be inferred from a letter supposedly sent to him on 28 April 1826 by Edward Tierney, the family’s Dublin solicitor and land agent, entreating him to ‘abandon his evil courses and his associates’.

“He decamped to Portugal in 1840, but after Mrs. Cleese’s death he returned to England, where he died in December 1841. Tierney was made sole executor and residuary legatee of the estate, exciting some comment, but it was not until 1857 that the will was finally proved (under £20,000) by Tierney’s son-in-law and heir, the Rev. Sir William Lionel Darell. In 1863 the will was belatedly contested by George James Perceval (1794-1874), Egmont’s cousin and successor in the peerage. It was alleged that alcoholism had rendered Egmont completely dependent on Tierney, whose misleading valuation of the estates had induced him to draw up his will as he did. The evidence was inconclusive and an out of court settlement was reached, by which the Irish property was returned to the Egmont family on payment of £125,000 to Darell. It was estimated that Tierney and his heirs had realized at least £300,000 from their stewardship of the estates, which were eventually sold by the 7th earl in 1889. The 8th earl (1856-1910), a former sailor turned London fireman, upheld family tradition by being arrested for drunkenness in Piccadilly, 16 May 1902.“

In 1814 Rev. Matthew Purcell (1773-1845) was resident. He lived there with his wife Elizabeth Leader. His father John passed his Highfort home in County Cork to his youngest son, Dr. Richard Purcell, and spent his latter years with his eldest son Matthew at Burton House, where he died in 1830.

The Annals of Churchtown (see [6]) tell us:

“John Purcell earned the sobriquet ‘the Knight of the Knife’ (occasionally the ‘Blood-red Knight’) for the spirited manner in which he, at some 80 years of age and, armed only with a knife, had repulsed a number of armed intruders at his Highfort home in Liscarroll [County Cork] on the 18th March 1811, killing three of their number and wounding others before the attackers fled. The attack not only earned a knighthood for Purcell. It also heralded a change in English law: it was determined henceforth that an octogenarian could kill in self-defence.“

The Landed Estates database tells us that the invaders were “Whiteboys.” Whiteboys were members of a secret agrarian organisation who defended tenant farmer land rights. Their members were called “whiteboys” after the white smocks they wore on their night time raids. Their activity began around 1760 when land which had previously been commonage was enclosed by landlords to farm cattle. [9]

The house bears the Purcell coat of arms on the central gable. The crest represents the encounter between Sir John Purcell the Octagenarian and the intruders he fought off.

Reverend Matthew Purcell was succeeded by his son John Purcell in 1845, at a time when the house was valued at £34. Reverend Matthew also had eight daughters.

The Sli Eile website tells us:

“Proceeding up the avenue, we can see the very fine parkland. On the right hand side is the new forestry plantation, started in 1997, which now covers a large part of the estate, and contains a very fine forest walk with much to interest both the arboriculturist and the casual walker. Further up, also on the right-hand side, may be seen a group of five mature oak trees, (one of which is unfortunately dead). These trees, of which there were once eight, were planted in the 1800’s to commemorate the birth of eight daughters of the Rev. Matthew Purcell, owner of Burton Park, and Rector of Churchtown. These trees are known as the eight sisters.“

John married Anna More Dempsey and they had two children: Matthew John (1852-1904) and Elizabeth Mary (believed to have been a nun, died unmarried, 1867). Matthew John, who inherited the property as a juvenile, was made a Ward of Court until he came of age.

Matthew Purcell bought Burton Park from the 7th Earl of Egmont in 1889. The 6th Earl of Egmont (John, 1794-1874) was the grandson of the 2nd Earl of Egmont and his second wife, Catherine Compton. His father was Charles George Perceval, who became 2nd Baron Arden after his mother’s death. The 6th Earl did not have any children, and it was a son of his brother Reverend Charles George Perceval who became the 7th Earl of Egmont (Charles George Perceval 1845-1897) and sold Burton Park.

In 1889 the Purcells undertook major renovations and alterations. [see 4]. Mark Bence Jones tells us that the Purcells refaced it in Victorian cement and gave it a high roof with curvilinear dormer-gables. [8] Frank Keohane tells us:

“Today the façade is rather more ornate, owing to a remodelling by William H. Hill c. 1899. Hill faced the house in rough plaster with smooth banded quoins, string courses and a cornice topped with a balustrade. The style is loosely Renaissance, with curvilinear gables and grotesque panels to the pedimented ground floor windows.“

William Henry Hill (1837-1911) was an architect from Cork. He was architect for the Dioceses of Down, Connor & Dromore under the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in 1860 until the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1870, when he set up in private practice in Cork. [10] The Dictionary of Irish Architects tells us that in addition to his privately commissioned work, he was diocesan architect for the Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross from 1872 until circa 1878.

On a website about Churchtown, Jim McCarthy writes about Burton Park and tells us more about the 1889 update:

“In the 1890s, through his agent Robert Sanders and in conjunction with the Board of Works, the Purcells embarked on imaginative (and expensive) alterations and improvements to the house and estate: bedroom floors were renewed, ceilings remoulded, chimney shafts rebuilt, a kitchen was added, pantries were provided, a porch built, slating and skylights were repaired and renewed, staircases removed or altered, and windows and shuttering replaced. Extensive work on the coach house, gate lodge, sheds and stables was also undertaken.” [11]

The website tells us that the roof was raised to accommodate the dormer windows, and the ornate architraves over the windows were also added at that time.

The gate lodge, built around 1890, was inhabited until fairly recently, and has one room on each side. It has a central section with Tudor arched carriageway straddling entrance road, and flanking lower single-bay screen walls.

There was nobody to greet us when we arrived to the house, despite my contacting the contact person listed for the property, the Manager for Slí Eile. However, the front door was open, so we entered and had a little wander around. We did not venture far, as we felt like intruders.

The porch has lovely tiling, and the front hall has good plasterwork ceiling and cornice.

The entrance leads into a large hall with beautiful plasterwork ceiling and sweeping staircase with thin balusters. Mark Bence-Jones tells us that the pedimented doorcases were added later.

The Slí Eile website tells us that about the Hall:

“The heavy oak carving of the fireplace and over mantel are of typical Edwardian style, as is the glass panelled door from the porch. In a glass-fronted bookcase at the back of the hall is an artefact with a very strange history. It is a carving knife carefully stored in a glass topped box. This knife has a curse on it, in that anyone who opens the box will die within the year. Needless to say, no-one has attempted this to date! The knife was the property of one John Purcell, of Highfort, Liscarroll, who received a knighthood in 1811 for defending himself, single-handedly, as a very old man against a number of burglars. He killed three of them with this knife, the rest fled. He is known as “The Knight of the Knife” as a result of this feat. At the time, it was made a rule in law that an octogenarian could kill in self defence.“

Matthew John Purcell married Anne Daly, daughter of Peter Paul Daly of Daly’s Grove, County Galway. He converted to Catholicism upon his marriage.

They had nine children. It was the son, John, of their daughter Anita, who in 1919 married John Ryan of Scarteen, Knocklong, County Limerick, who inherited Burton Park, and took the name Ryan-Purcell.

Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe interviewed Rosemary Ryan-Purcell, eldest daughter of John Ronan, The Grove, Rushbrooke, County Cork, who along with her husband John came to live at Burton Park with their two eldest children in the early 1960s. Rosemary explains the Ryan-Purcell connection to the old house. “This was the home of my husband John’s mother, whose name was Anita Purcell. He was the younger son, and his elder brother inherited the Ryan family home at Scarteen in Knocklong, County Limerick. When we were first married, we lived at Scarteen, which was John’s childhood home. Later, he inherited Rich Hill near Annacotty, County Limerick, from his godfather, Dicky Howley, and we lived there for a short while. When John’s aunt, Louisa Purcell, died in the early 1960s, she left Burton Park to John, so we then came to live here and have been here ever since.“

They now lease the property to Slí Eile. The Slí Eile website tells us of the drawing room:

“Decorated and furnished in the Louis Quinze style, in 1906, the furniture, carpet and wallpaper are all French. Note the very fine plasterwork on the ceiling and cornice. The architraves around the windows are all mid 18th century, as is most of the woodwork in this room. Over the small bureau by the far window is an artist’s impression of how the original house may have looked. It was originally thought that the house had never been built to this plan, but recent research shows that it is much more accurate than formerly imagined. This room also has a sprung floor, and in earlier days would have been used as a ballroom as well as a drawing room.“

Frank Keohane tells us:

“The three-bay drawing room has an Edwardian Louis XVI overlay of wallpaper framed in panels. The room and the hall have decent Neoclassical ceilings with especially wispy acanthus S-scrolls. The joinery in contrast is heavy and mid-Georgian in character, with cambered and lugged architraves, fielded panels and waterleaf carving, all no doubt the product of a provincial joiner not conversant with Neoclassical trends.”

John Ryan’s family also owned Edermine House in County Wexford.

Rosemary continues: “John’s Auntie Louise, “Lulu,” was the youngest of the Purcell daughters. She was unmarried and she lived here at Burton Park. She suffered from arthritis, and was confined to a wheelchair. She was a very brave woman indeed and she ran the place here on her own for years. When she died, John and I took over, we were asked to take on the Purcell name, and that’s why we are now the Ryan-Purcell family.”

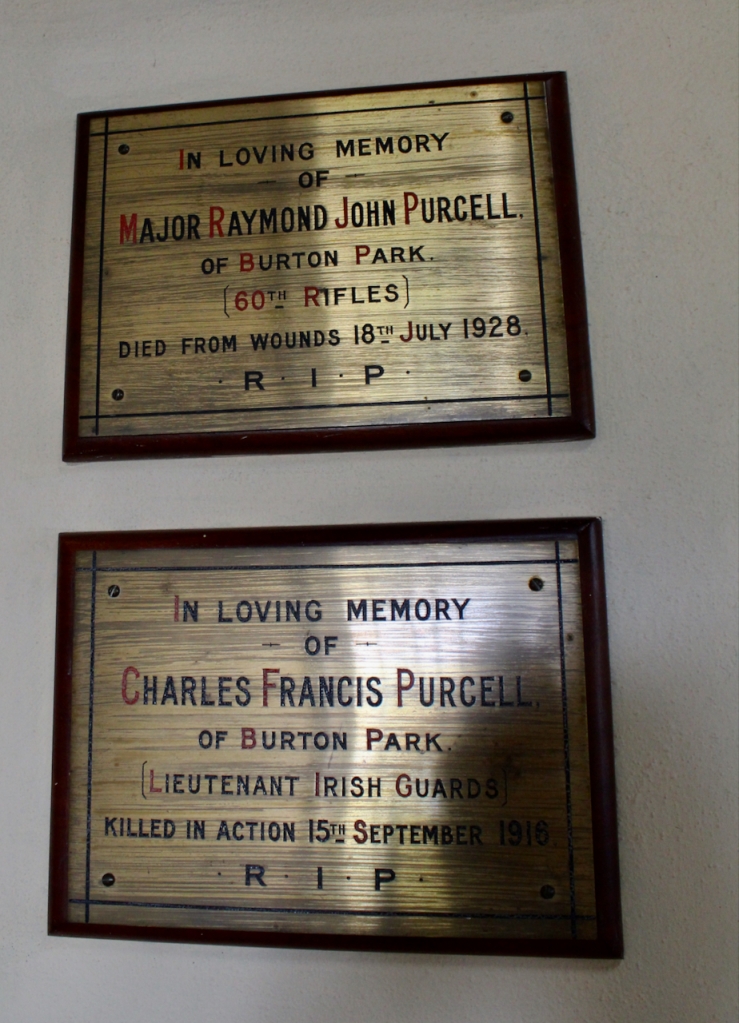

O’Hea O’Keeffe tells us that before they moved to Burton Park, Rosemary was already quite familiar with the house from her many earlier visits there, as John had been farming there before their marriage. “He had to come here to Burton Park straight after school. They used to say in the family that before he opened his eyes as an infant, he had been told by his mother than he would be coming here. This was her home, which she had visited with John almost every week during his childhood. John had two Purcell uncles who were born at Burton Park, both of whom were to lose their lives as a result of the First World War. Raymond, the older brother, tragically took his own life after his return from the war. His brother died at the Battle of the Somme.”

The Oratory is dedicated to the memory of the two Purcell sons who lost their lives as a result of the First World War.

When the Raymond Purcell was a young man, his mother purchased Curraghmount, near Buttevant, for use as a Dower House. His sisters Maisie and Louise moved there with their mother and stayed there for the remainder of Raymond’s lifetime. Following his tragic death after WWI, they returned to live in Burton Park.

While living at Burton Park, Raymond carried out large-scale improvements to the house, including the installation of a generator and electric light in 1912. Thus, the manor became one of the earliest properties in the parish to use electricity.

Residents of Burton House were quite self-sufficient: in addition to the game, meats, vegetables and fruits supplied by its farm, it had a cider press and two limekilns. They manufactured their own bricks, examples of which can be seen in the orchard walls. Thirty-five gardeners once laboured to maintain the bowling green, croquet lawn, tennis courts and parkland. [see 6]

John Ryan-Purcell was ‘a bit of a genius’ says his widow. He was able to keep the house in good repair, including electricity and plumbing, and he also milked his cattle. He had a Jersey herd at Burton Park.

Rosemary continues: “When John and I first came, there were thirty acres of woodland here, mostly scrub, and my husband cleared it and reclaimed the land. We also planted a great amount of woodland, to make ends meet really. Over four or five phases, we planted ninety acres. We also have fifty acres of pasture, and we are now involved in Rural Environmental Protection Scheme, and in organic farming.”

Jane O’Hea O’Keeffe writes: “The pleasure grounds at Burton Park were designed by Decimus Burton, who also designed Kew Gardens in London and Dublin’s Phoenix Park. Indigenous trees, such as beech and oak, grow very well here, and seed has been collected over the years.“

O’Hea O’Keeffe tells us that the copper beech tree on the front lawn was planted by John Ryan-Purcell’s grandmother. The original entrance consisted of a straight avenue down from the front door to the little church and graveyard where the Purcell family vault stands. Matthew Purcell, who bought Burton Park from the Earl of Egmont in 1889, was Church of Ireland rector here.

Unfortunately since there was nobody to show us around, we did not get to see the organic farm or the outbuildings, nor the swimming pool. We also didn’t see the stable range, of which Keohane writes: “The long stable range in the adjoining yard may contain the shell of the C18 stables, which were fitted up as a house for the rector by 1739.”

[1] www.slieile.ie

[2] p. 326, Keohane, Frank. The Buildings of Ireland. Cork City and County. Yale University Press: New Haven and London. 2020.

[3] p. 327, Keohane, Frank. The Buildings of Ireland. Cork City and County. Yale University Press: New Haven and London. 2020.

[4] p. 63. O’Hea O’Keeffe, Jane. Voices from the Great Houses: Cork and Kerry. Mercier Press, Cork, 2013.

[5] https://oglethorpe.edu/about/history-traditions/james-edward-oglethorpe/

[6] https://gerrymurphy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1.-The-Annals-of-Churchtown-854-Pages-9MB-20190222.pdf

[6] https://www.dib.ie/biography/perceval-percival-sir-john-a7275

[7] http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/perceval-henry-1796-1841

[8] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses, originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978; Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[9] Chapter 34, Cusack, Margaret Anne. An Illustrated History of Ireland (1868) https://www.libraryireland.com/HistoryIreland/Whiteboys.php

[10] https://www.dia.ie/architects/view/2581/HILL%2C+WILLIAM+HENRY+%5B1%5D

[11] http://churchtown.net/history/burton-park/

[12] https://www.purcellfamily.org/photographs Note that The castle at the Little Island, Co. Waterford was the seat of the Purcell-FitzGerald family (descendants of Lieutenant-Colonel John Purcell and his wife Mary FitzGerald) from circa 1818 to 1966. It is now the Waterford Castle Hotel. The Purcell-FitzGeralds were descendants of the Purcells of Ballyfoyle, Co. Kilkenny, an offshoot of the Purcells of Loughmoe.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com