General Information: castletown@opw.ie

From the OPW website:

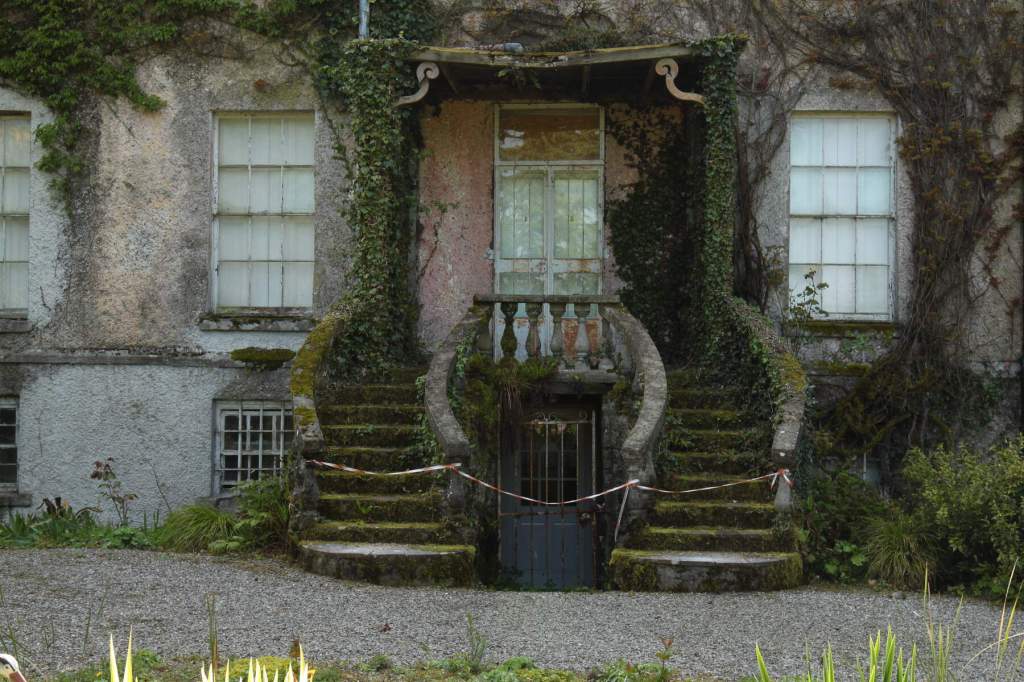

“Castletown is set amongst beautiful eighteenth-century parklands on the banks of the Liffey in Celbridge, County Kildare.

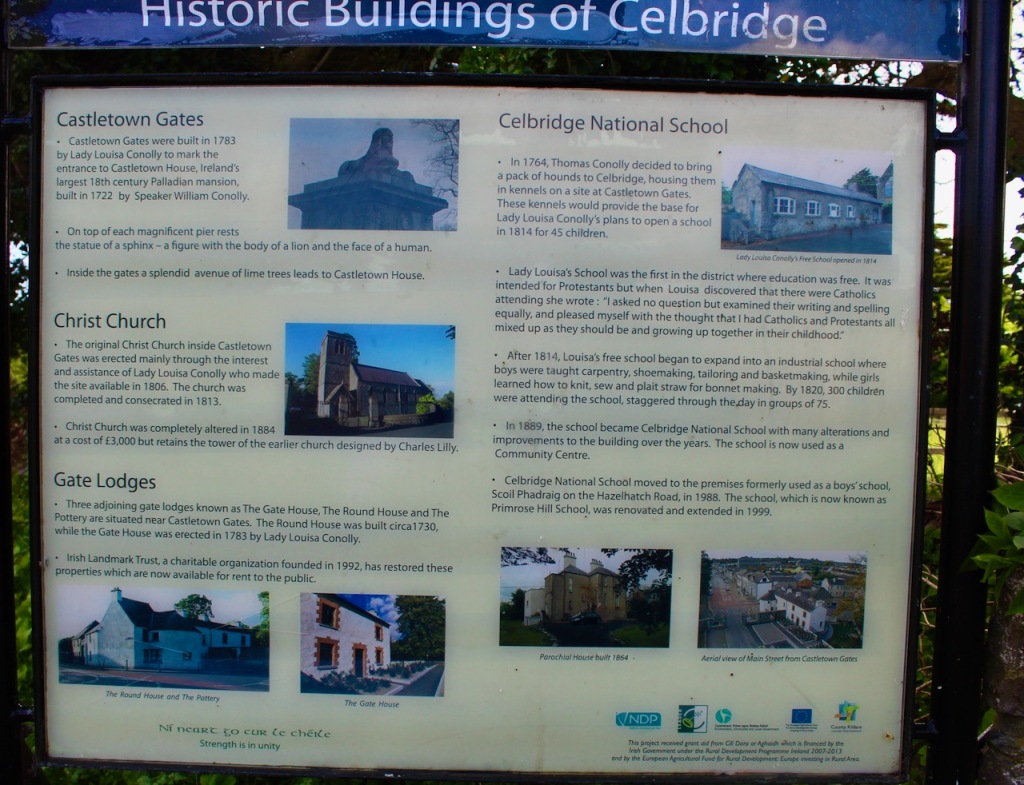

“The house was built around 1722 for the speaker of the Irish House of Commons, William Conolly, to designs by several renowned architects. It was intended to reflect Conolly’s power and to serve as a venue for political entertaining on a grand scale. At the time Castletown was built, commentators expected it to be ‘the epitome of the Kingdom, and all the rarities she can afford’.

“The estate flourished under William Conolly’s great-nephew Thomas and his wife, Lady Louisa, who devoted much of her life to improving her home.

“Today, Castletown is home to a significant collection of paintings, furnishings and objets d’art. Highlights include three eighteenth-century Murano-glass chandeliers and the only fully intact eighteenth-century print room in the country.

“It is still the most splendid Palladian-style country house in Ireland.“

The Conolly family sold Castletown in 1965. Mark Bence-Jones tells us that the estate was bought for development and for two years the house stood empty and deteriorating. In 1967, Hon Desmond Guinness courageously bought the house with 120 acres, to be the headquarters of the Irish Georgian Society, and in order to save it for posterity. Since then the house has been restored and it now contains an appropriate collection of furniture, pictures and objects, which has either been bought for the house, presented to it by benefactors, or loaned. It is now maintained by the Office of Public Works and the Castletown Trust.

William Conolly (1662-1729) rose from modest beginnings to be the richest man in Ireland in his day. He was a lawyer from Ballyshannon, County Donegal, who made an enormous fortune out of land transactions in the unsettled period after the Williamite wars.

William Conolly had property on Capel Street in Dublin, before moving to Celbridge. Conolly’s house was on the corner of Capel Street and Little Britain Street and was demolished around 1770. [2] The Kildare Local History webpage gives us an excellent description of William Conolly’s rise to wealth:

“In November 1688, William Conolly was one of the Protestants who fled Dublin to join the Williamites in Chester alongside his late Celbridge neighbour Bartholomew Van Homrigh.

“On the victory of William III, he acquired a central role dealing in estates forfeited by supporters of James II, commencing his rise to fortune with the forfeited estates of the McDonnells of Antrim.

“In 1691 he purchased Rodanstown outside Kilcock, which became his country residence until he purchased Castletown in 1709.

“A dowry of £2,300 came his way in 1694 when he married Katherine Conyngham, daughter of Albert Conyngham, a Williamite General who had been killed in the war at Collooney in 1691.

“He was appointed Collector and Receiver of Revenue for the towns of Derry and Coleraine on May 2nd 1698.

“Conolly was the largest purchaser of forfeited estates in the period 1699–1703, acquiring also 20,000 acres spread over five counties at a cost of just £7,000.” [3]

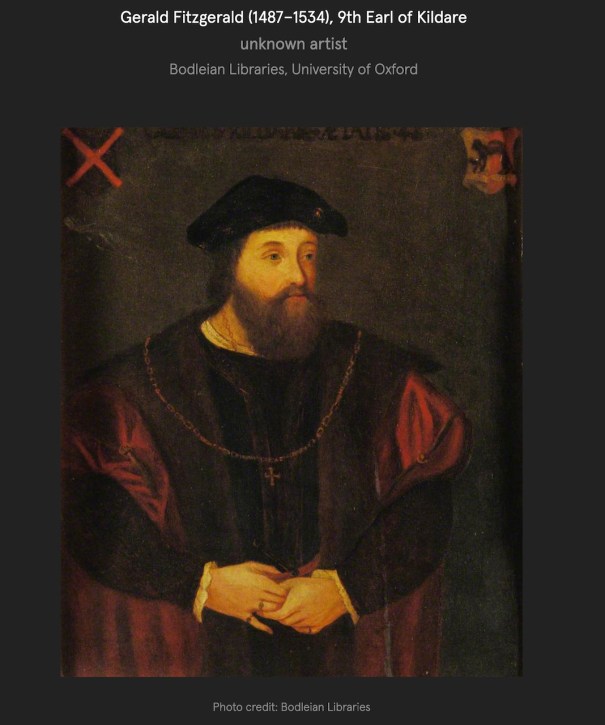

William Conolly purchased land in County Kildare which had been owned by Thomas Dongan (1634-1715), 2nd Earl of Limerick, in 1709. Dongan’s estate had been confiscated as he was a Jacobite supporter of James II (he became first governor of the Duke of York’s province of New York! The Earldom ended at his death). Dongan’s mother was the daughter of William Talbot, 1st Baronet of Carton (see my entry about Carton, County Kildare, under Places to stay in County Kildare https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/06/08/places-to-visit-and-stay-in-county-kildare/ ).

Conolly rose to become Speaker of the House of Commons in the Irish Parliament. He married Katherine Conyngham of Mount Charles, County Donegal, whose brother purchased Slane Castle in County Meath (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2019/07/19/slane-castle-county-meath/). As well as earning money himself, his wife brought a large dowry.

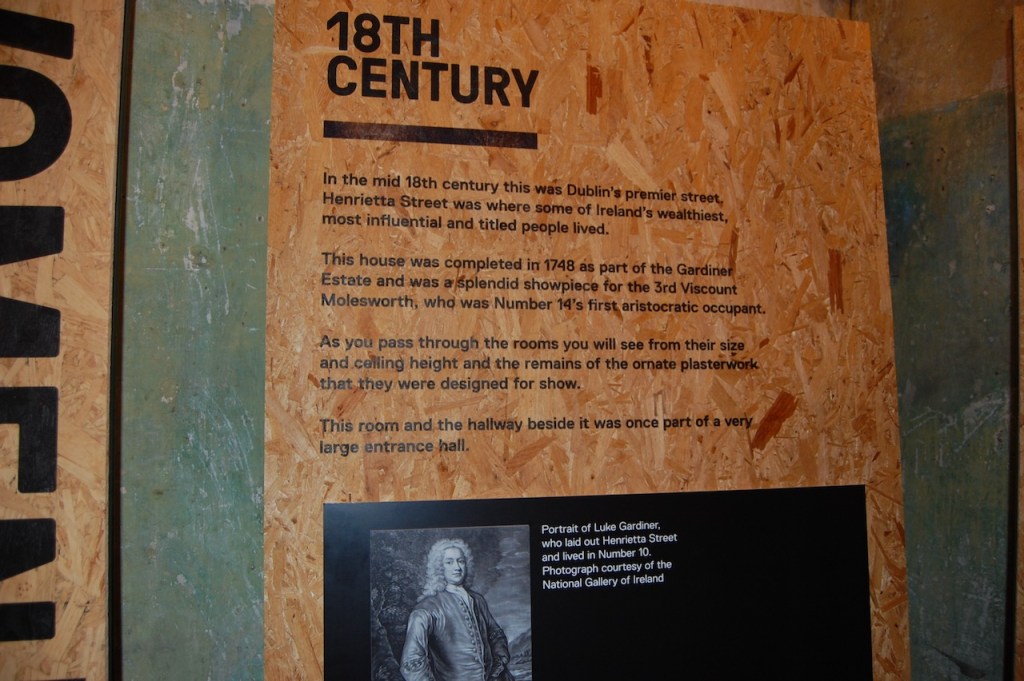

The Archiseek website tells us about the design of Castletown House:

“Soon after the project got underway Conolly met Alessandro Galilei (1691-1737), an Italian architect, who had been employed in Ireland by Lord Molesworth in 1718 [John Molesworth, 2nd Viscount, who had been British envoy to Florence]. He designed the façade of the main block in the style of a 16th century Italian town palace. He returned to Italy in 1719 and was not associated with the actual construction of the house which began in 1722. Sir Edward Lovett Pearce (died 1733), a young Irish architect, on his Italian grand tour became acquainted with Galilei in Florence and through this connection he was employed by the Speaker to complete Castletown when he returned to Ireland in 1724. Pearce had first hand knowledge of the work of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) and his annotated copy of Palladio’s Quattro libri dell’architettura survives. It was Pearce who added the Palladian colonnades and the terminating pavillions. This layout was the first major Palladian scheme in Ireland and soon had many imitators.” [4]

Mark Bence-Jones describes Castletown in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses. The centre block is of three storeys over basement, and has two almost identical thirteen bay fronts “reminiscent of the façade of an Italian Renaissance town palazzo; with no pediment or central feature and no ornamentation except for doorcase, entablatures over the ground floor windows, alternate segmental and triangular pediments over the windows of the storey above and a balustraded roof parapet. Despite the many windows and the lack of a central feature, there is no sense of monotony or heaviness; the effect being one of great beauty and serenity.” [5] The centre block is made of Edenderry limestone, and is topped by cornice and balustrade. On the ground floor the windows have frieze, cornice and lugged architrave, and on the first floor, alternating triangular and segmental pediments.

Pearce added the curved Ionic colonnades and two two-storey seven bay wings. He also designed the impressive two-storey entrance hall inside.

William died in 1729 aged just 67, so he had only a few years to enjoy his house. His wife Katherine lived on in the house another twenty-three years until her death at the age of 90 in 1752. William and Katherine had no children, so his estate passed to his nephew William James Conolly (1712-1754), son of William’s brother Patrick. We came across William James Conolly before in Leixlip Castle (another Section 482 property), which he also inherited. William James married Lady Anne Wentworth, the daughter of the Earl of Strafford. Her father, Thomas Wentworth 1st Earl of Strafford is not the more famous Thomas Wentworth 1st Earl of Strafford who was executed (of whom there is at least one portrait in Castletown) but a later one, of the second creation. William James died just two years after Katherine Conolly, so the estate then passed to his son Thomas Conolly (1738-1803).

Thomas married Louisa Lennox in 1758, one of five Lennox sisters, daughters of the Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond. From the age of eight she had lived at nearby Carton with her sister Emily, who was married to James Fitzgerald, the 20th Earl of Kildare (who became the 1st Duke of Leinster). At Carton, Louisa was exposed to the fashionable ideas of the day in architecture, decoration, horticulture and landscaping. [6] Louisa loved Castletown and continually planned improvements, planting trees, designing the lake and building bridges.

Archiseek continues: “The Castletown papers, estate records and account books, together with Lady Louisa’s [i.e. Louisa Lennox, wife of Tom Conolly] diaries and correspondence with her sisters, provide a valuable record of life at Castletown and also of the reorganisation of the house. Lady Louisa’s letters from the 1750s onwards are revealing of the fashions in costume design, fabric patterns and furniture. She played an important part in the alteration and redecoration of Castletown during the 1760s and 1770s. As no single architect was responsible for all of the work carried out, she supervised most of it herself. Much of the redecoration of the house was done to the published designs of the English architect Sir William Chambers (1723-1796) who never came to Ireland himself. Chambers also worked for Lady Louisa’s brother, the 3rd Duke of Richmond, at Goodwood in Sussex. In a letter, written in July 1759, Lady Louisa mentions instructions given by Chambers to his assistant Simon Vierpyl who supervised the work at Castletown.” (see [6])

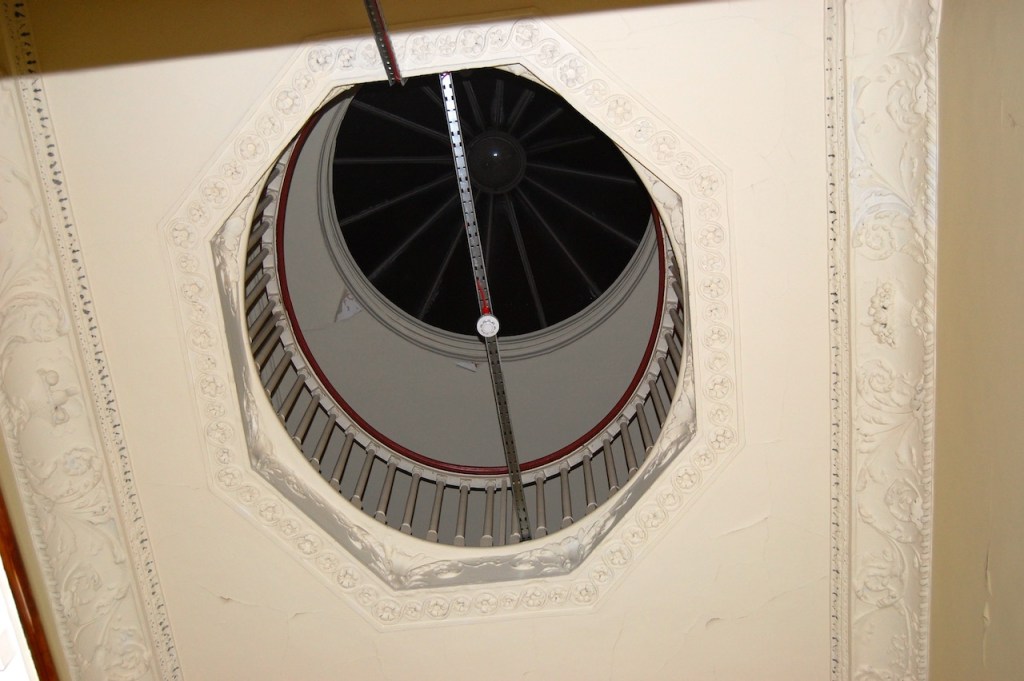

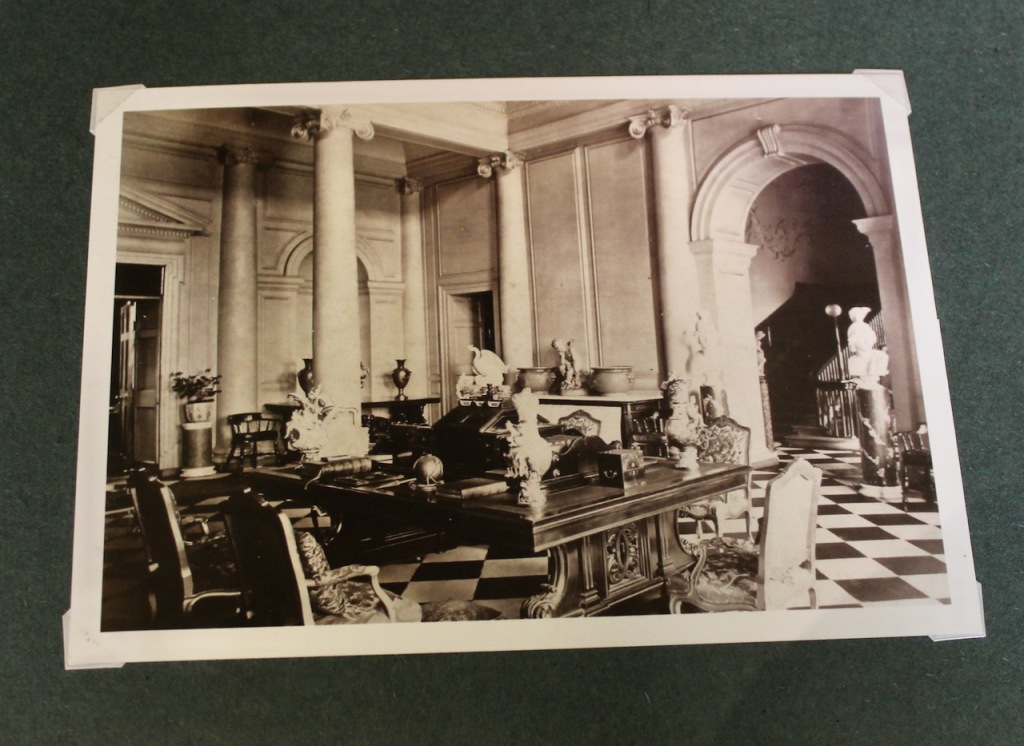

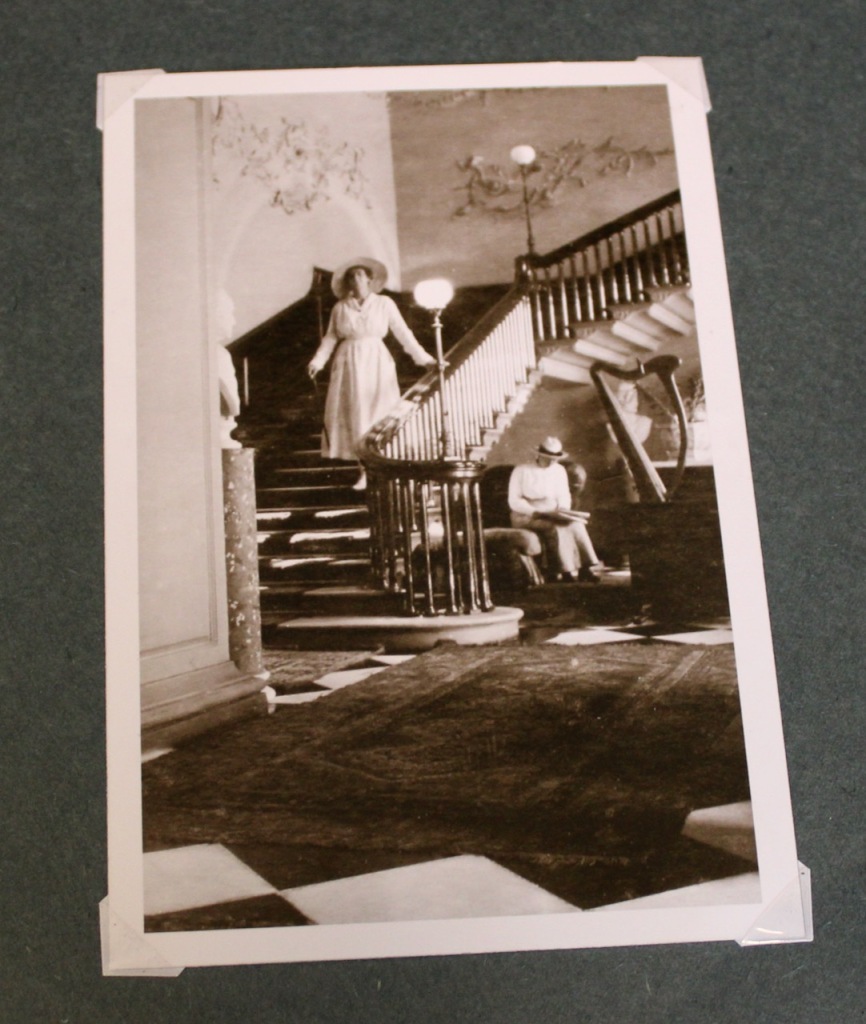

Description of the Hall, from Archiseek: “This impressive two-storeyed room with a black and white chequered floor, was designed by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce. The Ionic order on the lower storey is similar to that of the colonnades outside and at gallery level there are tapering pilasters with baskets of flowers and fruit carved in wood. The coved ceiling has a central moulding comprising a square Greek key patterned frame and central roundel with shell decoration.” [see 6]

The polished limestone floor with its chequered design and the Kilkenny marble fireplace reflect William Conolly’s desire to build the house solely of native Irish materials. Unfortunately when we visited in October 2022, the hall was half hidden with a large two storey curtain, as the windows are all being repaired. As we can see in the photograph, the room has an Ionic colonnade to the rear, and a gallery at first floor level, and the stair hall is through an archway in the east wall.

When the owners were selling off the items in the house, they tried to sell the picture of Leixlip Castle that is in the front hall over the fireplace. It turned out to be painted on to the wall, so had to remain in the house! See my entry about Leixlip Castle https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/09/04/leixlip-castle-county-kildare-desmond-guinnesss-jewelbox-of-treasures/

From the entrance hall, one enters the magnificent Stair Hall. The Castletown website describes the stair hall:

“The Portland stone staircase at Castletown is one of the largest cantilevered staircases in Ireland. It was built in 1759 under the direction of the master builder Simon Vierpyl (c.1725–1811). Prior to this the space was a shell, although a plan attributed to Edward Lovett Pearce suggests that a circular staircase was previously intended.

“The solid brass balustrade was installed by Anthony King, later Lord Mayor of Dublin. He signed and dated three of the banisters, ‘A. King Dublin 1760’. The opulent rococo plasterwork was created by the Swiss-Italian stuccadore Filippo Lafranchini, who, with his older brother Paolo, had worked at Carton and Leinster House for Lady Lousia’s brother-in-law, the first Duke of Leinster, as well as at Russborough in Co. Wicklow. Shells, cornucopias, dragons and masks feature in the light-hearted decoration which represents the final development of the Lafranchini style. Family portraits are also included with Tom Conolly at the foot of the stairs and Louisa above to his right. The four seasons are represented on the piers and on either side of the arched screen.“

Image Number: 873959 Publication Date: 22/08/1936 Country Life Volume: LXXX Page: 196

Photographer: A.E.Henson.

Mark Bence-Jones continues:

“In the following year, Tom Conolly and Lady Louisa employed the Francini to decorate the walls of the staircase hall with rococo stuccowork; and in 1760 the grand staircase itself – of cantilevered stone, with a noble balustrade of brass columns – was installed; the work beign carried out by Simon Vierpyl, a protégé of Sir William Chambers. The principal reception rooms, which form an enfilade along the garden front and were mostly decorated at this time, are believed to be by Chambers himself; they have ceilings of geometrical plasterwork, very characteristic of him. Also in this style is the dining room, to the left of the entrance hall. It was here that, according to the story, Tom Conolly found himself giving supper to the Devil, whom he had met out hunting and invited back, believing him to be merely a dark stranger; but had realised the truth when his guest’s boots were removed, revealing him to have unusually hairy feet. He therefore sent for the priest, who threw his breviary at the unwelcome guest, which missed him and cracked a mirror. This, however, was enough to scare the Devil, who vanished through the hearthstone. Whatever the truth of this story, the hearthstone in the dining room is shattered, and one of the mirrors is cracked.“

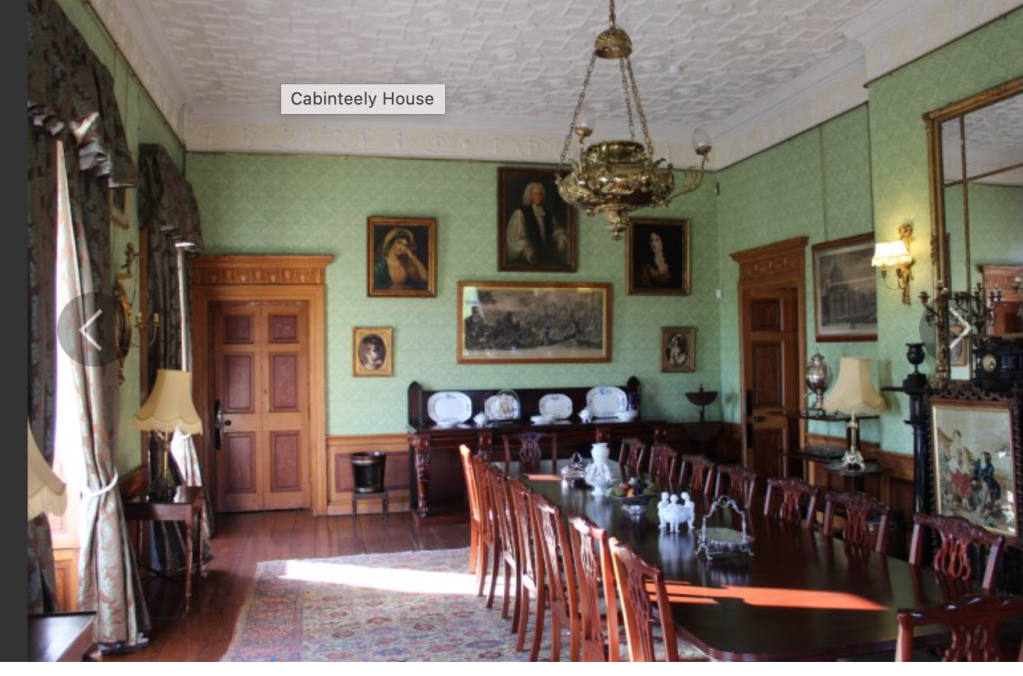

The Dining Room, description from Archiseek:

“This room dates from the 1760s redecoration of Castletown undertaken by Lady Louisa Conolly and reflects the mid-eighteenth century fashion for separate dining rooms. Originally, there were two smaller panelled rooms here. It was reconstructed to designs by Sir William Chambers, with a compartmentalised ceiling similar to one by Inigo Jones in the Queen’s House at Greenwich. The chimney-piece and door cases are in the manner of Chambers. Of the four doors, two are false.

“Furniture original to Castletown includes the two eighteenth-century giltwood side tables. Their frieze is decorated with berried laurel foliage similar to the door entablatures in the Red and Green Drawing Rooms. The three elaborate pier glasses are original to the Dining Room. The frames are carved fruiting vines, symbols of Bacchus and festivity. These are probably the work of the Dublin carver Richard Cranfield (1713-1809) who, with the firm of Thomas Jackson of Essex Bridge, Dublin, was paid large sums for carving and gilding throughout the house.“

Between the front of the house, with its Entrance Hall, Stair Hall and Dining Room is a corridor, or rather, two corridors, one to the west and one to the east of the Entrance Hall. This corridor is on every storey, including the basement. To the rear (north) of the house on the ground floor is an enfilade of rooms: the Brown Study to the west end, next to another staircase, then the Red Drawing Room, the Green Drawing Room, the Print Room, the State Bedroom, and then small rooms called the Healy Room and the Map Room.

The corridors now hold paintings and art works, and one has a cabinet of Meissen porcelain.

Next to the Dining Room at the front of the house is the Butler’s Pantry, which contains photographs of the servants of Castletown, and a portrait of a housekeeper, Mrs Parnel Moore (1649–1761). It’s unusual to have a portrait of a housekeeper but perhaps someone painted her because she was a beloved member of the household, as she lived to be at least 112 years! This is a very old portrait dating back to the 1700s.

The Castletown website tells us about the Butler’s Pantry: “The Butler’s Pantry dates from the 1760s and connected the newly created Dining Room with the kitchens in the West Wing. Food was carried in from the kitchens through the colonnade passageway and then reheated in the pantry before being served. The great kitchens were on the ground floor of the west wing, with servants’ quarters upstairs. Upwards of 80 servants would have been employed in the house and kitchens in the late eighteenth century under the direction of the Butler and the Housekeeper.”

The Red Drawing Room, description from Archiseek:

“It is one of a series of State Rooms that form an enfilade and were used on important occasions in the eighteenth century. This room was redesigned in the mid 1760s in the manner of Sir William Chambers. The chimney-piece, ceiling and pier glasses are typical of his designs.

“The walls are covered in red damask which is probably French and dates from the 1820s. Lady Shelburne recorded in her journal seeing a four coloured damask, predominently red, in this room. The Aubusson carpet dates from about 1850 and may have been made for the room. Much of the furniture has always been in the house and Lady Louisa Conolly paid 11/2 guineas for each of the Chinese Chippendale armchairs which she considered very expensive. The chairs and settee were made in Dublin and they are displayed in a formal arrangement against the walls as they would have been in the eighteenth century. The bureau was made for Lady Louisa in the 1760s.“

The neoclassical ceiling, which replaced the vaulted original, is based on published designs by the Italian Renaissance architect, Sebastiano Serlio, and is modelled after one in Leinster House (belonging to Lady Louisa’s sister’s husband the Earl of Kildare). The white Carrara chimney-piece came to the house in 1768.

The Green Drawing Room, description from Archiseek:

“The Conollys formally received important visitors to the house in the Green Drawing Room which was the saloon or principal reception room. The room was redecorated in the 1760s and like the other state rooms reflects the neo-classical taste of the architect Sir William Chambers. The Greek key decoration on the ceiling is repeated on the pier glasses and the chimney-piece. Originally these were pier tables with a Greek key frieze and copies of these may be made in the future. The chimney-piece is similar to one designed by Chambers for Lord Charlemont’s Casino at Marino.”

The Castletown website tells us: “The Green Drawing Room was the main reception room or saloon on the ground floor. Visitors could enter from the Entrance Hall or the garden front. Like the other state rooms it was extensively remodelled between 1764 and 1768. The influence of the published designs of Serlio and the leading British architect Isaac Ware can be seen in the neo-classical ceiling, door cases and chimney-piece...The walls were first lined with a pale green silk damask in the 1760s. Fragments of this silk, which was replaced by a dark green mid-nineteenth century silk, survived and the present silk was woven as a direct colour match in 1985 by Prelle et Cie in Lyon, France.”

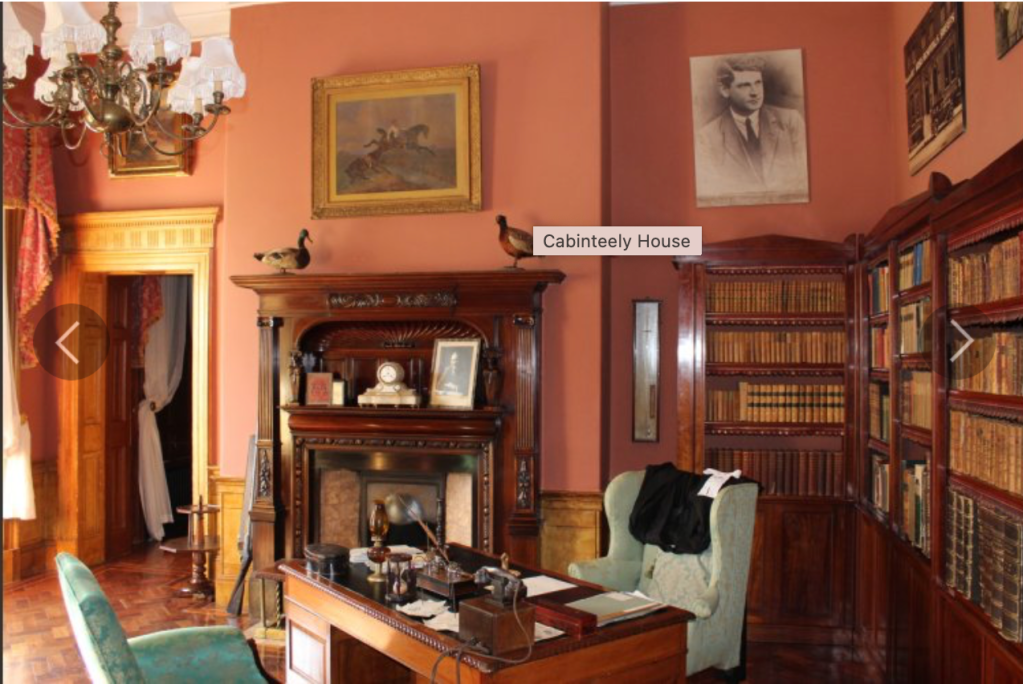

The Brown Study is at one end of this enfilade of rooms. The website describes it:

“The Brown Study with its wood-panelled walls, tall oak doors, corner chimney-piece, built-in desk and vaulted ceiling is decorated as it was in the 1720s when the house was first built. This room was used as a bedroom in the late nineteenth century and then as a breakfast parlour in the early twentieth century.

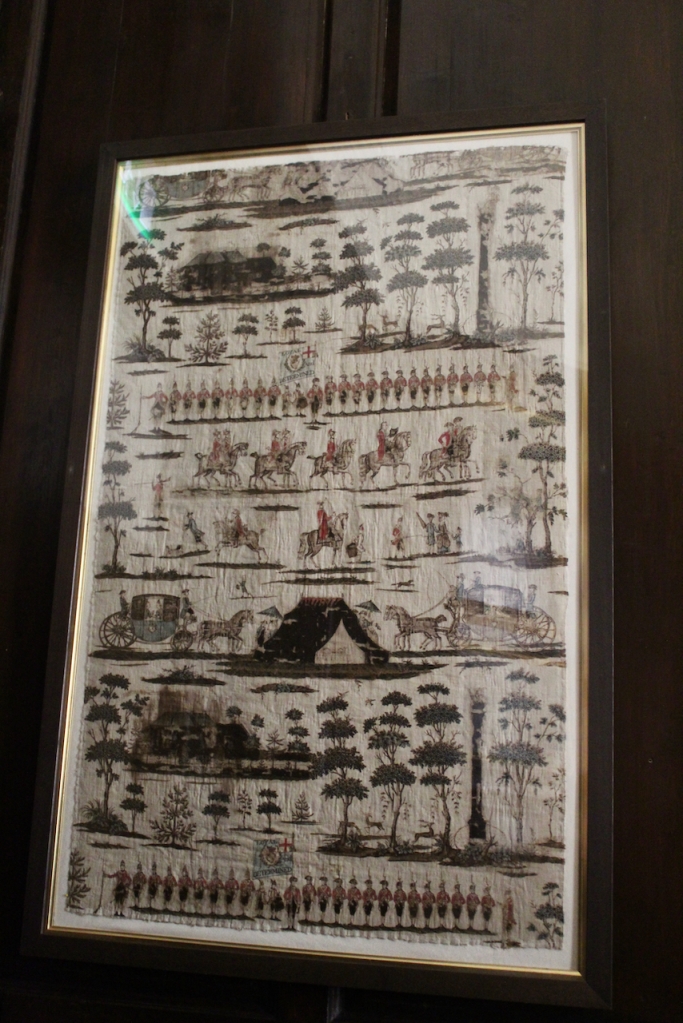

Between the windows is a piece of the ‘Volunteer fabric’. Printed on a mixture of linen and cotton in Harpur’s Mills in nearby Leixlip, it depicts the review of the Leinster Volunteers in the Phoenix Park in 1782. Thomas Conolly was active in the Volunteer leadership in both Counties Derry and Kildare. The Volunteers were a local militia force established during the American War of Independence to defend Ireland from possible French invasion while the regular troops were in America. They were later linked to the Patriot party in the Irish House of Commons led by Henry Grattan and to their campaigns for political reform.“

Mark Bence-Jones continues: “The doing-up of the house was largely supervised by Lady Louisa, and two of the rooms bear her especial stamp: the print room, which she and her sister, Lady Sarah Napier made ca. 1775; and the splendid long gallery on the first floor, which she had decorated with wall paintings in the Pompeian manner by Thomas Riley 1776.“

The website tells us about the Print Room, completed in 1769: “More than any other room in Castletown, the Print Room bears the imprint of Lady Louisa, who assiduously collected, cut out, and arranged individual prints, frames and decorations. The prints were glued on panels of off-white painted paper which was later attached to the walls on battens covered with cloth. Lady Louisa thus created an intimate, highly individual room which has survived changing tastes and fashions and is now the only fully intact eighteenth-century print room in Ireland.”

Print rooms were fashionable in the 18th century – ladies would collect their favourite prints and paste the walls with them. Prints featured include Le Bas, Rembrandt and Teniers, the actor David Garrick and Sarah Cibber, Louisa’s sister Sarah, Charles I and Charles II as a boy, with whom Louisa shared a bloodline.

The room was later used as a billiards room, and this helped inadvertedly to save the prints, as our guide told us, as the smoke from their pipes helped to protect against silverfish insects which eat wallpaper.

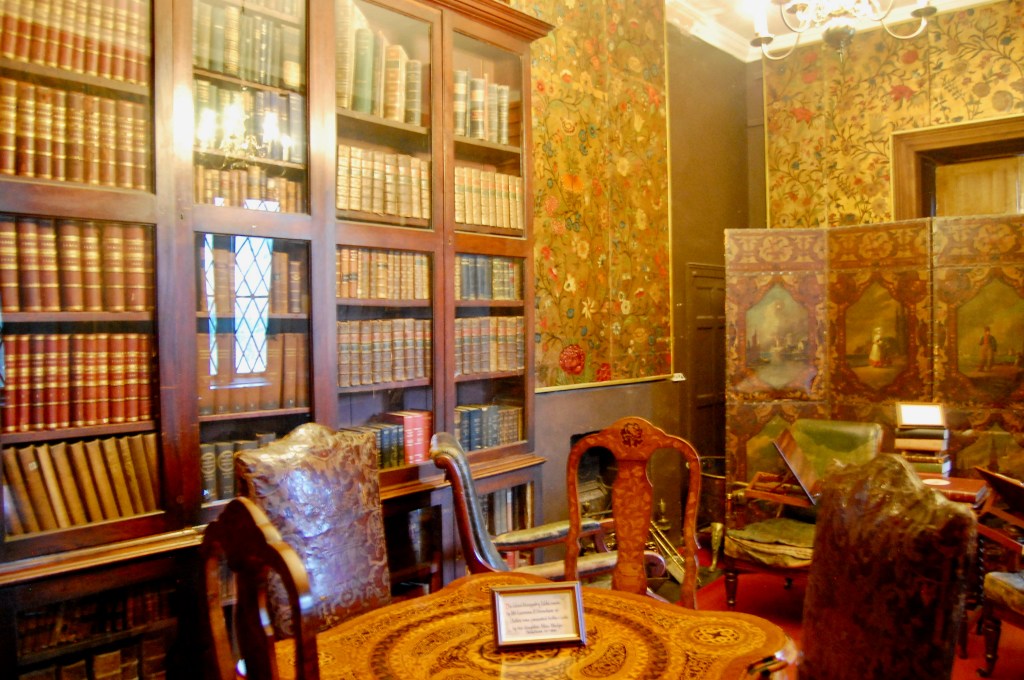

Next to the Print Room is the State Bedroom. The website tells us:

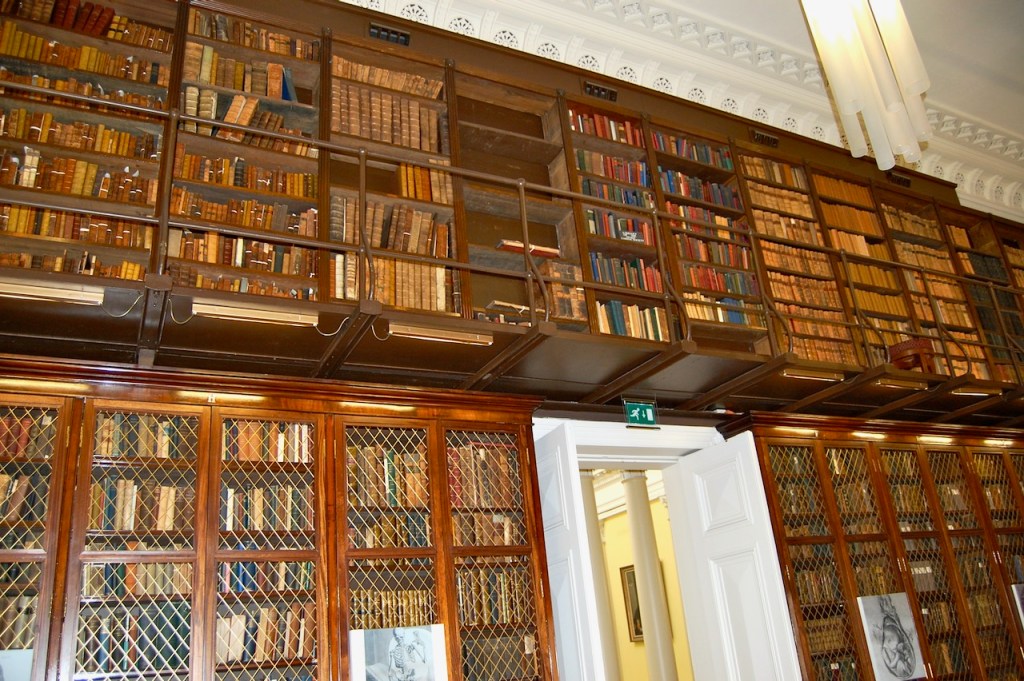

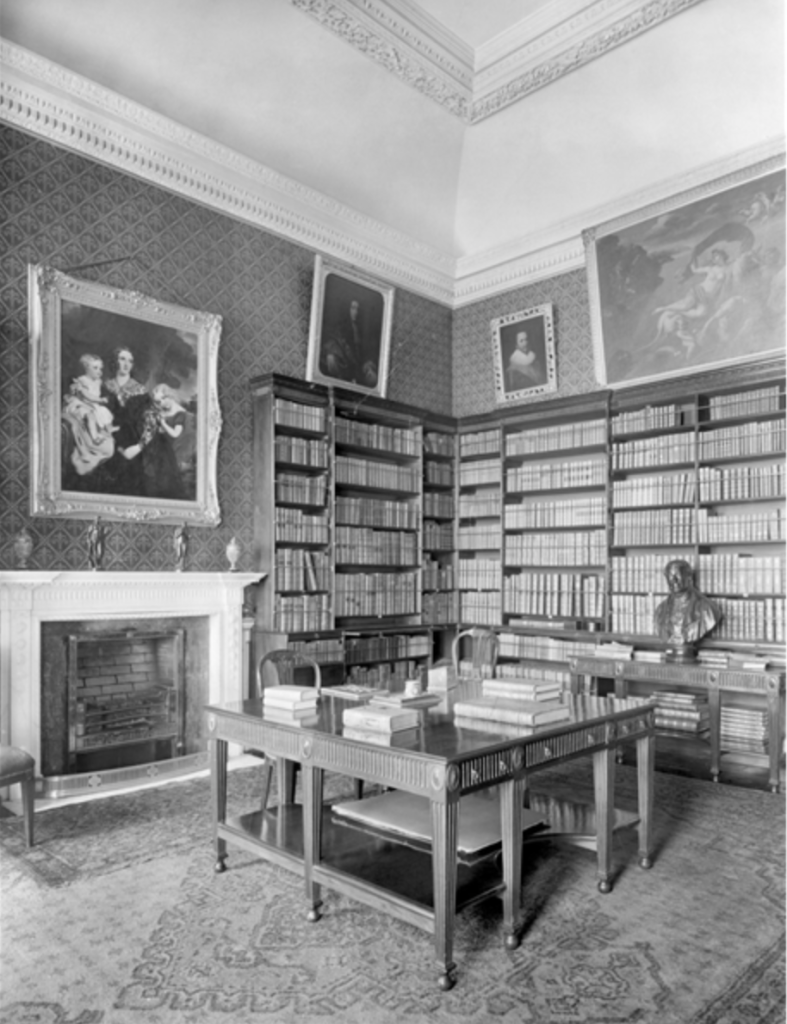

“In the 1720s, when the house was first laid out, this room, along with the rooms either side, probably formed William Conolly’s bedroom suite. It was intended that he would receive guests in the morning while sitting up in bed or being dressed in the manner of the French court at Versailles. In the nineteenth century, the room was converted into a library and the mock leather Victorian wall paper dates from this time. Sadly, the Castletown library was dispersed in the 1960s and today the furniture reflects the room’s original use.“

Image Number: 873961 Publication Date: 22/08/1936 Volume: LXXXPage: 196

Photographer: A.E. Henson.

Next to the State Bedroom is The Healy Room: “This room originally served as a dressing room or closet attached to the adjoining State Bedroom. It was used as a small sitting room and later became Major Edward Conolly’s bedroom in the mid-twentieth century, as it was one of the few rooms that could be kept warm in winter. It is now known as the Healy room after the pictures of the Castletown horses by the Irish artist Robert Healy (d.1771).”

Upstairs has more bedrooms, and the beautiful Long Gallery. A corridor overlooks the Great Hall.

To one side of the Stair Hall upstairs is Lady Kildare’s Room, named after Lady Louisa’s sister Emily, Countess of Kildare and later Duchess of Leinster, who had raised Louisa and the two younger sisters Sarah and Cecilia at nearby Carton House after their parents’ death. Currently being renovated, in the past the room housed the Berkeley Costume Collection. Made in France, Italy, and England, the dresses on display consist of rich embroidered bodices and full skirts made from silk and gold thread.

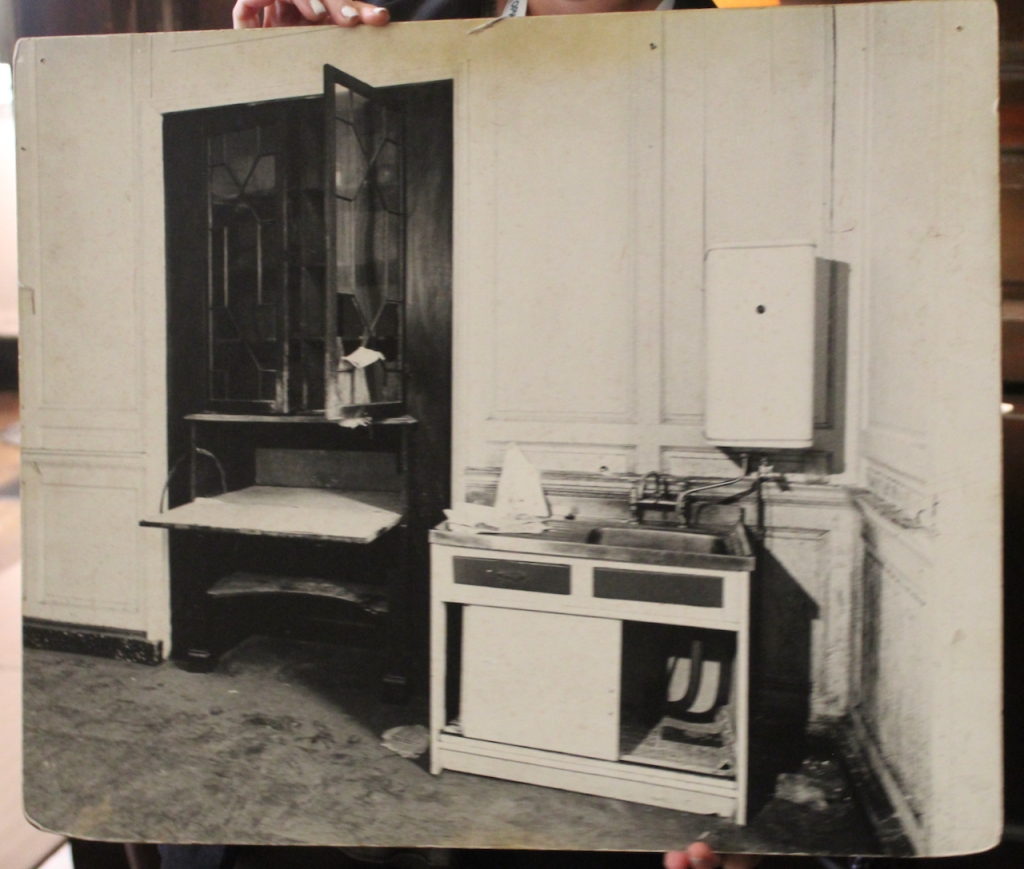

Across the upstairs East Corridor from Lady Kildare’s room is the Blue Bedroom. The website tells us that the Blue Bedroom provides a fine example of an early Victorian bedroom. Like the Boudoir, it forms part of an apartment with two adjoining dressing rooms, one of which was upgraded into a bathroom with sink and bathtub. The principal bedrooms, used by the family and honoured guests, were on this floor. Bedrooms on the second floor were also used for guests and for children, while the servants slept in the basement. This room has a lovely pink canopied bed, but we did not see the room when we visited in 2022.

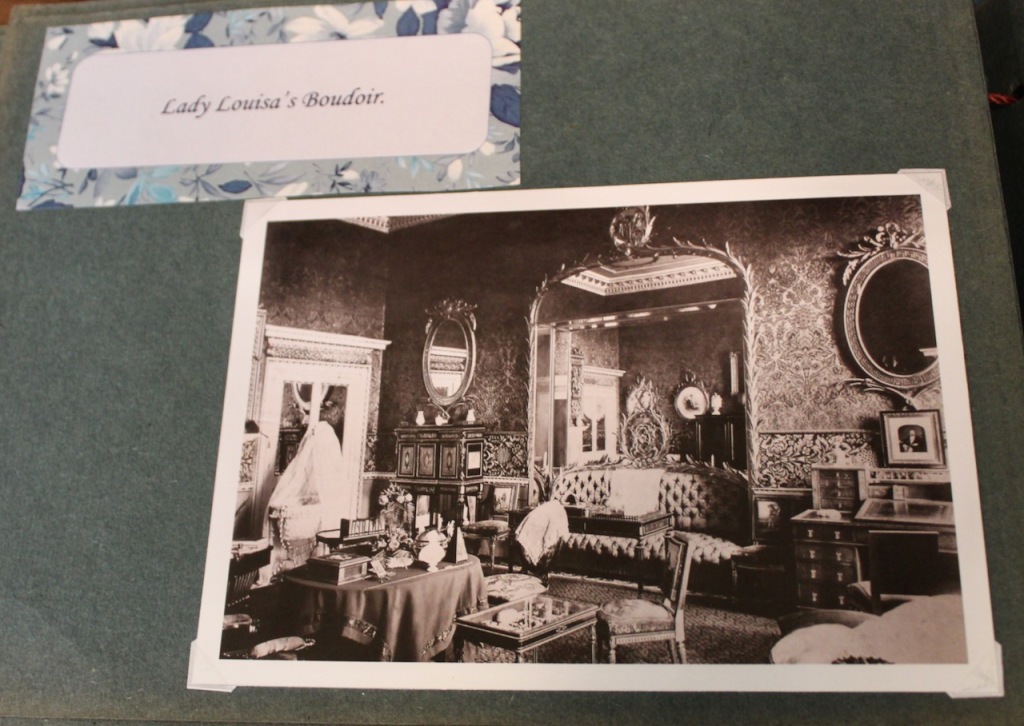

At the front of the house on the other side of the Great Hall upstairs are the Boudoir, and Lady Louisa’s Bedroom, and across the West Corridor upstairs, the Pastel Room. The website tells us:

“The Boudoir and the adjoining two rooms formed Lady Louisa’s personal apartment. The Boudoir served as a private sitting room for Louisa and subsequent ladies of the house. The painted ceiling, dado rail and window shutters possibly date from the late eighteenth century and were restored in the 1970s by artist Philippa Garner. The wall panels, or grotesques, after Raphael date from the early nineteenth century and formerly hung in the Long Gallery. Amongst the items inside the built-in glass cabinet are pieces of glass and china featuring the Conolly crest.

“In the adjoining room, Lady Louisa’s Bedroom, OPW’s conservation architects have left exposed the walls to offer visitors a glimpse of the different historic layers in the room, from the original brick walls, supported by trusses, to wooden panelling to fragments of whimsical printed wall paper that once embellished the room.“

Across the West Corridor upstairs is the Pastel Room. The Corridor has more portraits.

The Pastel Room, the website tells us, was originally an anteroom to the adjoining Long Gallery. It was used as a school room in the nineteenth century and is now known as the Pastel Room because of the fine collection of pastel portraits. The smaller pastels surrounding the fireplace include a pair of portraits of Thomas and Louisa Conolly by the leading Irish pastel artist of the eighteenth century, Hugh Douglas Hamilton.

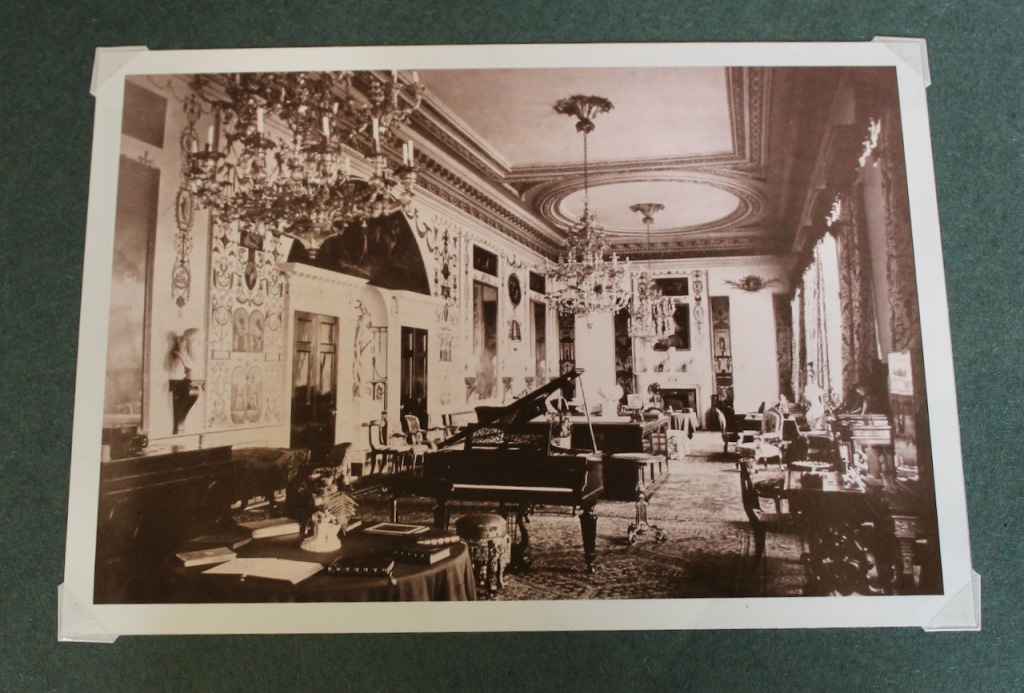

From the Pastel Room, we enter the Long Gallery. The website tells us about this room:

“Originally laid out as a picture gallery with portraits of William Conolly’s patrons on display, its function and layout changed under Lady Louisa. In 1760, she had the original doorways to the upper east and west corridors removed, replacing them with the central doorway above the Entrance Hall. The new doorcases as well as new fireplaces at either end were designed by leading English architect, Sir William Chambers, while the actual execution was overseen by Simon Vierpyl. The Pompeian style decoration on the walls dates from the 1770s and was inspired by Montfaucon’s publications on the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum and by Raphael’s designs for the Vatican. The murals were the work of an English artist and engraver Charles Ruben Riley (1752–98). The Long Gallery became a space for informal entertaining and was full of life and activity as the following excerpt from one of Louisa’s letters suggests: “Our gallery was in great vogue, and really is a charming room for there is such a variety of occupations in it, that people cannot be formal in it. Lord Harcourt was writing, some of us played at whist, others at billiards, Mrs Gardiner at the harpsichord, others at chess, others at reading and supper at one end. I have seldom seen twenty people in a room so easily disposed of.”

Photographer: A.E. Henson.

The Long Gallery, description from Archiseek:

“…measuring almost 80 by 23 feet, with its heavy ceiling compartments and frieze dates from the 1720s. Originally there were four doors in the room and the walls were panelled in stucco similar to the entrance Hall. In 1776 the plaster panels and swags were removed but traces of them were found behind the painted canvas panels when they were taken down for cleaning during recent conservation work.”

Archiseek continues: “In the mid 1770s the room was redecorated in the Pompeian manner by two English artists, Charles Reuben Riley (c.1752-1798) and Thomas Ryder (1746-1810). Tom and Louisa’s portraits are at either end of the room over the chimney-pieces and the end piers are decorated with cyphers of the initals of their families: The portrait of Lady Louisa is after Reynolds (the original is in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard) and that of Tom after Anton Raphael Mengs (the original is in the National Gallery of Ireland).

Archiseek tells us: “The subjects of the wall paintings were mostly taken from engraving in d’Hancarville’s Antiquites Etrusques, Greques, et Romaines (1766-67) and de Montfaucon’s L’antiquite expliquee et representee en figures (1719). The busts of the poets and philosophers are placed on gilded brackets designed by Chambers. In the central niche stands a seventeenth-century statue of Diana. Above is a lunette of Aurora, the godess of the dawn, derived from a ceiling decoration by Guido Reni, the seventeenth century Bolognese painter.

“The three glass chandeliers were made for the room in Venice and the four large sheets of mirrored glass came from France. In the 1770s the Long Gallery was used as a living room and was filled with exquisite furniture. Originally in the room, there were a pair of side tables attributed to John Linnell, with marble tops attributed to Bossi, a pair of commodes by Pierre Langlois, that were purchased in London for Lady Louisa by Lady Caroline Fox and a pair of bookcases at either end of the room.

“In 1989 major conservation work was carried out on the Long Gallery. The wall paintings that had been flaking for many years were conserved. The original eighteenth-century gilding has been cleaned and the chandeliers restored. The project was funded by the American Ireland Fund, the Irish Georgian Society and by private donations.“

Mark Bence-Jones tells us: “The gallery, and the other rooms on the garden front, face along a two mile vista to the Conolly Folly, an obelisk raised on arches which was built by Speaker Conolly’s widow 1740, probably to the design of Richard Castle. The ground on which it stands did not then belong to the Conollys, but to their neighbour, the Earl of Kildare, whose seat, Carton, is nearby. The folly continued to be a part of the Carton estate until 1968, when it was bought by an American benefactress and presented to Castletown. At the end of another vista, the Speaker’s widow built a remarkable corkscrew-shaped structure for storing grain, known as the Wonderful Barn. One of the entrances to the demesne has a Gothic lodge, from a design published by Batty Langley 1741. The principal entrance gates are from a design by Chambers.“

The Obelisk, or Conolly Folly, was reputedly built to give employment during an episode of famine. It was restored by the Irish Georgian Society in 1960.

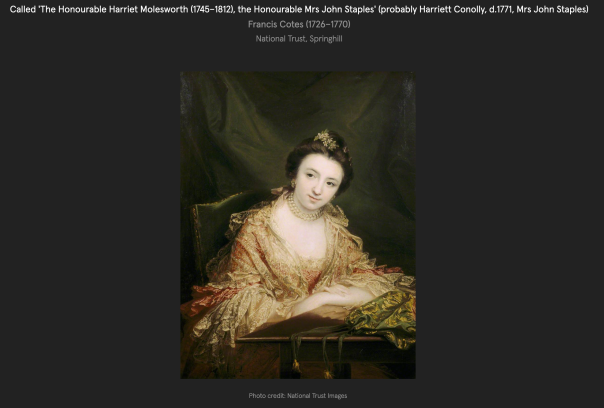

As Bence-Jones tells us, Castletown was inherited by Tom Conolly’s nephew, Edward Michael Pakenham, who took the name of Conolly, to become Pakenham Conolly. Thomas and Louisa had no children, and Thomas’s sister Harriet married John Staples, and their daughter was Louisa Staples. Louisa married Thomas Pakenham (1757-1836). It was their son, Edward Michael (1786-1849) who inherited Castletown.

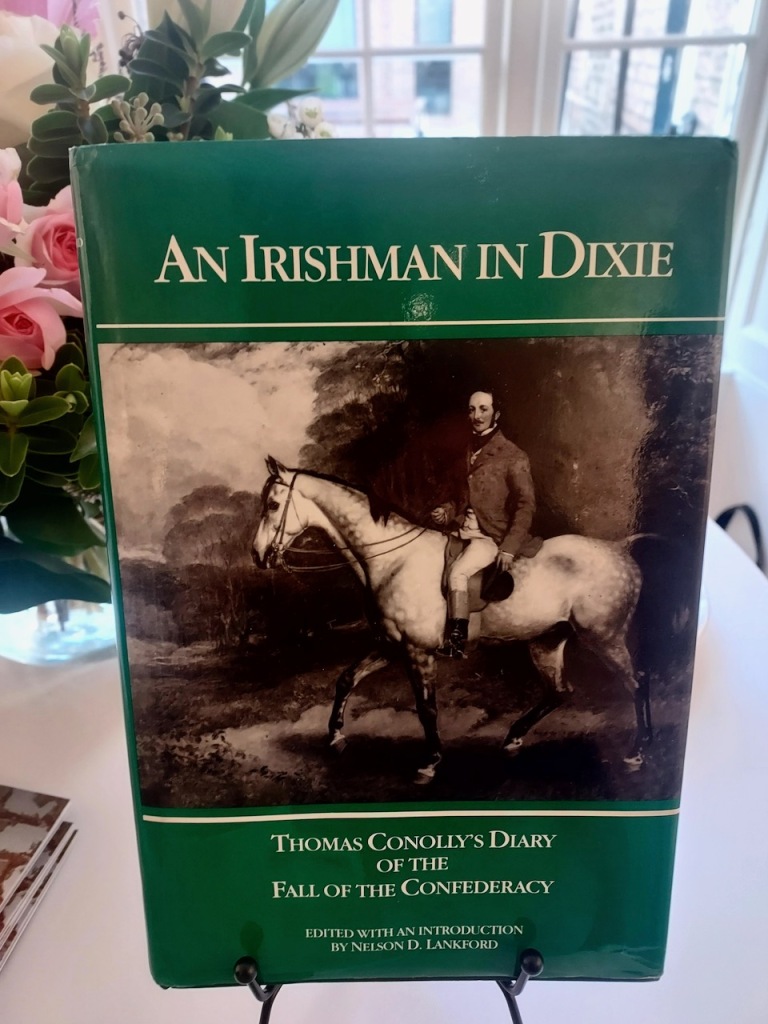

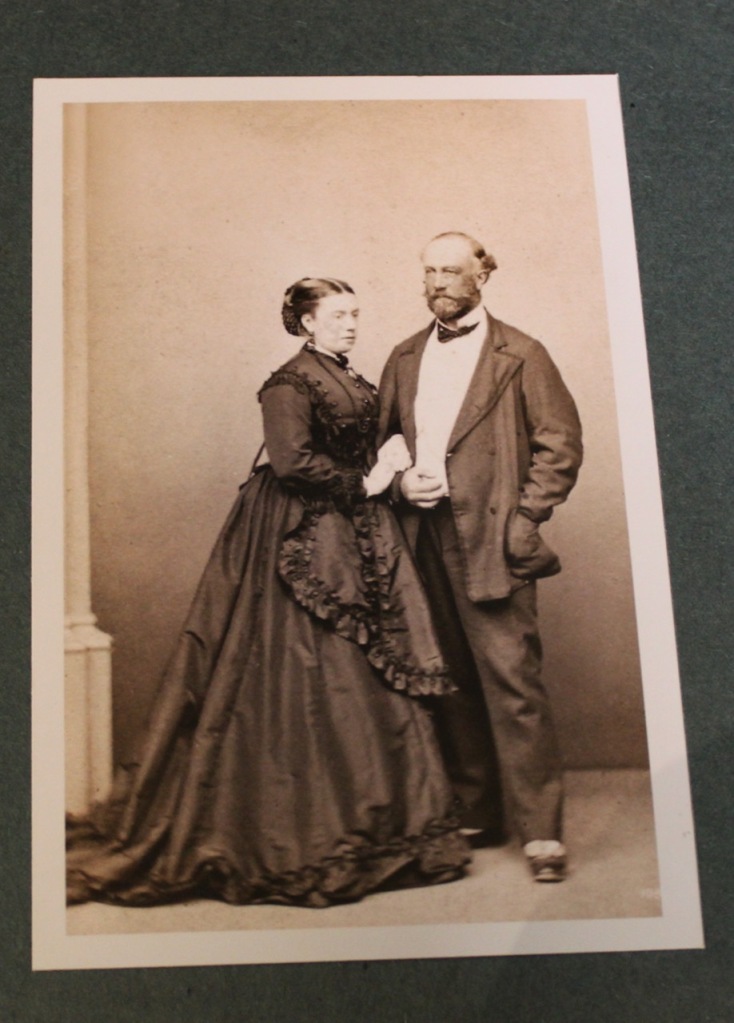

The house then passed to his son, another Thomas Conolly (1823-1876). He was an adventourous character who travelled widely and kept a diary. Stephen and I recently attended a viewing of portraits of Thomas and his wife Sarah Eliza, which are to be sold by Bonhams. His diary of his trip to the United States during the time of the Civil War is being published.

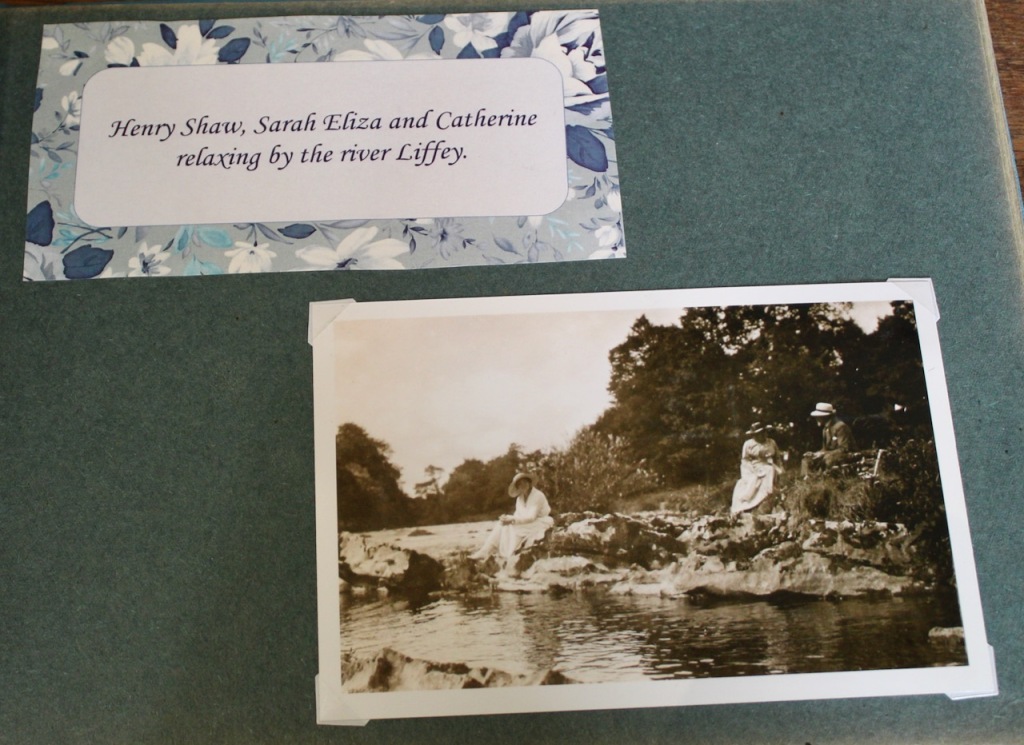

Sarah Eliza was the daughter of a prosperous Celbridge paper mill owner, Joseph Shaw. Her substantial dowry helped to fund her husband’s adventurous lifestyle! A photograph album which belonged to her brother Henry Shaw, of a visit to Castletown, was rescued from the rubble of his home in London when it was destroyed by a German bomb in 1944. Sadly, he died in the bombing. The photograph album is on display in Castletown.

Sarah Eliza and Thomas had four children. Thomas, born in 1870, died in the Boer War in 1900. William died at the age of 22. Edward Michael (Ted), born in 1874, lived until his death in Castletown, in 1956. Their daughter Catherine married Gerald Shapland Carew, 5th Baron Carew, the grandson of Robert Carew, 1st Baron Carew of Castleboro House, County Wexford (today an impressive ruin), and son of Shapland Francis Carew and his wife Hester Georgiana Browne, daughter of Howe Peter Browne, 2nd Marquess of Sligo.

Catherine’s son, William Francis Conolly-Carew (1905-1994), 6th Baron Carew, inherited Castletown, and added Conolly to his surname.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com

[2] p. xiii, Jennings, Marie-Louise and Gabrielle M. Ashford (eds.), The Letters of Katherine Conolly, 1707-1747. Irish Manuscripts Commission 2018. The editors reference TCD, MS 3974/121-125; Capel Street and environs, draft architectural conservation area (Dublin City Council) and Olwyn James, Capel Street, a study of the past, a vision of the future (Dublin, 2001), pp. 9, 13, 15-17.

[3] http://kildarelocalhistory.ie/celbridge

[4] https://archiseek.com/2011/1770s-castletown-house-celbridge-co-kildare/

[5] p. 75. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[6] p. 129. Great Irish Houses. Forewards by Desmond FitzGerald, Desmond Guinness. IMAGE Publications, 2008.

[3] p. 8, Living Legacies: Ireland’s National Historic Properties in the Care of the OPW. Government Publications, Dublin 2, 2018.

[9] https://castletown.ie/collection-highlights/

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com