On the map above:

blue: places to visit that are not section 482

purple: section 482 properties

red: accommodation

yellow: less expensive accommodation for two

orange: “whole house rental” i.e. those properties that are only for large group accommodations or weddings, e.g. 10 or more people.

green: gardens to visit

grey: ruins

Munster’s counties are Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford.

For places to stay, I have made a rough estimate of prices at time of publication:

€ = up to approximately €150 per night for two people sharing (in yellow on map);

€€ – up to approx €250 per night for two;

€€€ – over €250 per night for two.

For a full listing of accommodation in big houses in Ireland, see my accommodation page: https://irishhistorichouses.com/accommodation/

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Clare:

1. Barntick House, Clarecastle County Clare – section 482

2. Bunratty Castle, County Clare

3. Craggaunowen Castle, Kilmurray, Sixmilebridge, County Clare

4. Dunguaire Castle, Kinvara, County Clare

5. Kilrush House, County Clare – ‘lost,’ Vandeleur Gardens open

6. Knappogue or Knoppogue Castle, County Clare

7. Mount Ievers Court, Sixmilebridge, County Clare

8. Newtown Castle, Newtown, Ballyvaughan, County Clare – section 482

9. O’Dea’s, or Dysert Castle, County Clare

Places to Stay, County Clare

1. Armada House, formerly Spanish Point House, Spanish Point, County Clare €

2. Ballinalacken Castle, Lisdoonvarna, County Clare – hotel €€

3. The Carriage Houses, Beechpark House, Bunratty, County Clare €

4. Clare Ecolodge, formerly Loughnane’s, Main Street, Feakle, Co Clare

5. Dromoland Castle, Newmarket-on-Fergus, Co. Clare – hotel €€€

6. Falls Hotel (was Ennistymon House), Ennistymon, Co. Clare €€

7. Gregan’s Castle Hotel, County Clare €€€

8. Loop Head Lightkeeper’s Cottage, County Clare €€ for 2; € for 4-6

9. Mount Callan House and Restaurant, Inagh, County Clare – B&B

10. Mount Cashel Lodge, Kilmurry, Sixmilebridge, County Clare €

11. Newpark House, Ennis, County Clare €

12. Smithstown Castle (or Ballynagowan), County Clare € for 4-8 for one week

13. Strasburgh Manor coach houses, Inch, Ennis, County Clare €

Whole House Rental, County Clare

1. Inchiquin House, Corofin, County Clare – whole house rental € for 6-10

2. Mount Vernon lodge, County Clare – whole house accommodation € for 7-11 people

Clare:

1. Barntick House, Clarecastle Co. Clare V95 FH00 – section 482

contact: Ciarán Murphy

Tel: 086-1701060

Open dates in 2025: May 1-31, June 1-30, 4.30pm-8.30pm, Aug 16-24, 2pm-6pm

Fee: Free

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/11/06/barntick-house-clarecastle-county-clare/

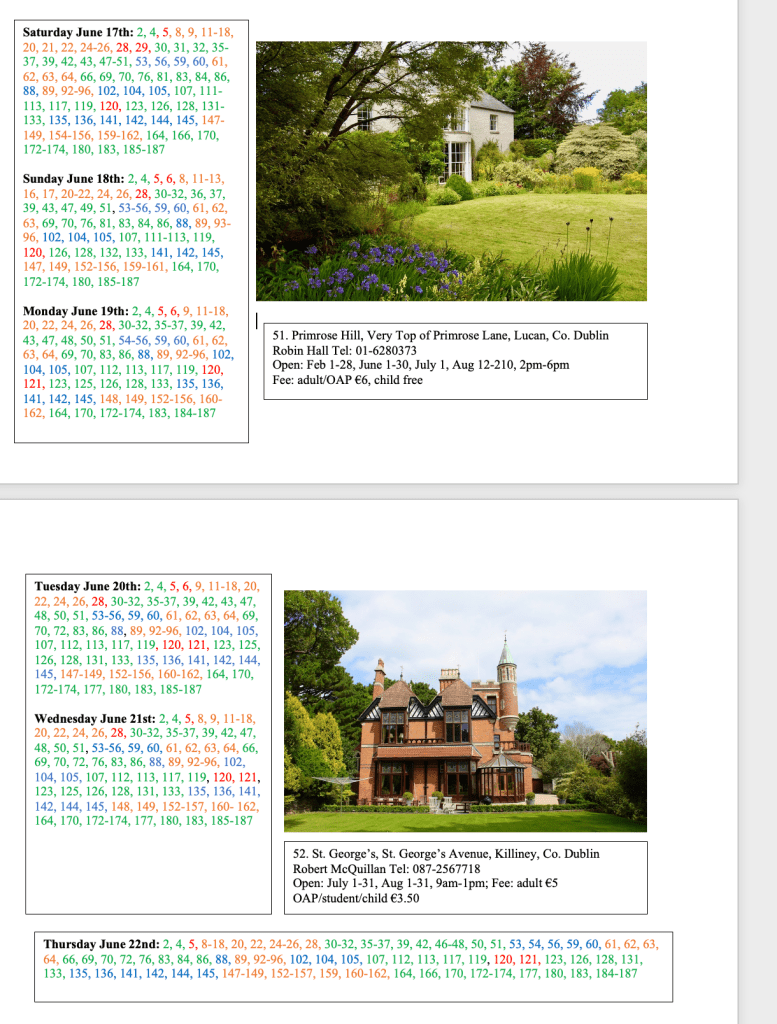

This house dates back to 1665!

2. Bunratty Castle, County Clare

maintained by Shannon Heritage

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses:

p. 49. “(O’Brien, Inchiquin, B/PB; and Thomond, E/DEP; Studdert/IFR; Russell/IFR; Vereker, Gort, VPB) One of the finest 15C castles in Ireland, standing by the side of a small tidal creek of the Shanon estuary; built ca 1425, perhaps by one of the McNamaras; then held by the O’Briens, who became Earls of Thomond, until 6th Earl [Barnabas O’Brien (d. 1657)] surrendered it to the Cromwellian forces during the Civil War. A tall, oblong building, it has a square tower at each corner; these are linked, on the north and south sides, by a broad arch just below the topmost storey. The entrance door leads into a large vaulted hall, or guard chamber, above which is the Great Hall, the banqueting hall and audience chamber of the Earls of Thomond, with its lofty timber roof. Whereas the body of the castle is only three storeys – there being another vaulted chamber below the guard chamber – the towers contain many storeys of small rooms, reached up newel stairs and by passages in the thickness of the walls. One of these rooms, opening off the Great Hall, is the chapel, which still has its original plasterwork ceiling of ca 1619, richly adorned with a pattern of vines and grapes. There are also fragment of early C17 plasterwork in some of the window recesses. After the departure of the O’Briens, a C17 brick house was built between the two north towers; Thomas Studdert [1696-1786], who bought Bunratty early in C18, took up residence here in 1720. Later, the Studderts built themselves “a spacious and handsome modern residence in the demesne: and the castle became a constabulary barracks, falling into disrepair so that, towards the end of C19, the ceiling of the Great Hall collapsed. Bunratty was eventually inherited by Lt-Com R.H. Russell, whose mother was a Studdert, and sold by him to 7th Viscount Gort [Standish Robert Gage Prendergast Vereker (1888-1975)] 1956. With the help of Mr Percy Le Clerc and Mr John Hunt, Lord Gort carried out a most sympathetic restoration of the castle, which included removing C17 house, re-roofing the Great Hall in oak and adding battlements to the towers. The restored castle contains Lord Gort’s splendid collection of medieval and C16 furniture, tapestries and works of art, and is open to the public; “medieval banquets” being held here as a tourist attraction. Since the death of Lord Gort, Bunratty and its contents have been held in trust for the Nation.” [2]

3. Craggaunowen Castle, Kilmurray, Sixmilebridge, County Clare

– history park, maintained by Shannon Heritage, www.craggaunowen.ie

The Irish Homes and Garden website tells us:

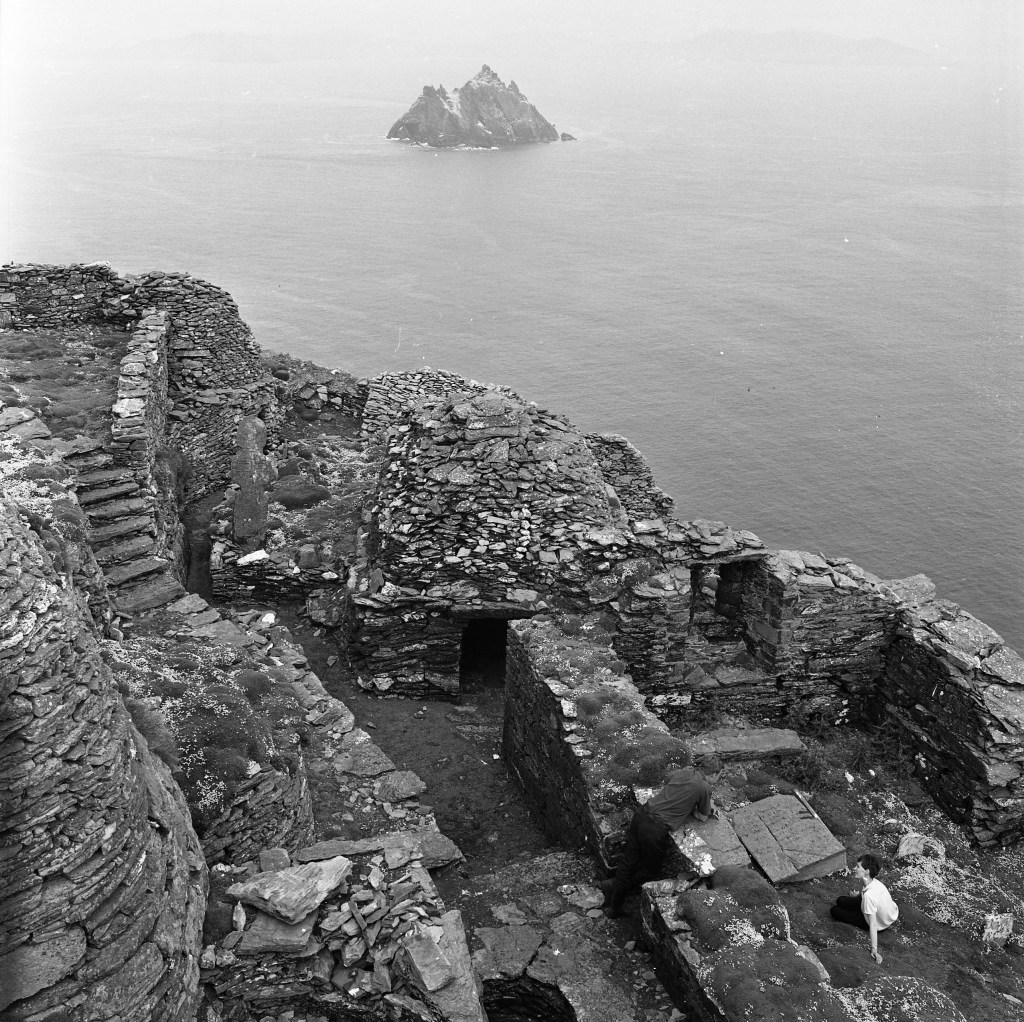

“Early medieval 500AD-1500: The most common form of house style during this period was the ringfort –a circular area of earth surrounded by a bank and ditch. In some cases, stone was used in the defensive enclosure and these are known as cashels. Over 45,000 examples still remain today. Also dating from this period were crannogs (from the Irish crann – tree) – an artificial island built in the shallow areas of lakes with the houses surrounded by a timber palisade or fence. These can be spotted in the landscape as small tree covered islands close to the lake shore – both the ringforts and crannogs most commonly contained circular houses. A reconstruction of a crannog dwelling can be found at Craggaunowen, Co. Clare

“This was also a time when Christianity was introduced to Ireland and whereas the early churches of the 6th and 7th centuries were of timber, evidence of stone churches appear from the late 8th century. These were simple rectangular buildings of about 5m long with a high steep pitched roof. The only doorway had a flat-topped lintelled opening. The early Irish monasteries of the 9th and 10th centuries, such as Clonmacnoise, had larger churches and monastic buildings also included the drystone beehive hut or clochan, as can be seen at Skellig Michael, and also the Round Tower, built between the 10th and 12th century, which consisted of a narrow tower up to 30m high tapering at the top with a conical roof.” [4]

The Craggaunowen website tells us: “Craggaunowen Castle - built by John MacSioda MacNamara in 1550 a descendant of Sioda MacNamara who built Knappogue Castle in 1467. After the collapse of the Gaelic Order, in the 17th century, the castle was left roofless and uninhabitable. The Tower House remained a ruin until it and the estate of Cullane House across the road, were inherited in 1821 by ”Honest” Tom Steele, a confederate of Daniel O’Connell, Steele had the castle rebuilt as a summer house in the 1820s. He used it and the turret on the hill opposite for recreation. His initials can be seen on one of the quoin-stones to the right outside. “The Liberator”. By the time of the First Ordnance Survey, in the 1840s, the castle was “in ruins”. After Steele in 1848 the lands were divided, Cullane going to one branch of his family, Craggaunowen to another, his niece Maria Studdert. Eventually the castle and grounds were acquired by the “Irish Land Commission”. Much of the land was given over to forestry and the castle itself was allowed to fall into disrepair. In the mid-19th century, the castle, herd’s house and 96 acres were reported in the possession of a Reverend William Ashworth, who held them from a Caswell (a family from County Clare just north of Limerick). In 1906, a mansion house here was owned by Count James Considine (from a family based at Derk, County Limerick). Craggaunowen Castle was restored by John Hunt in the 1960s – he added an extension to the ground floor, which for a while housed part of his collection of antiquities. The collection now resides in the Hunt Museum in the city of Limerick.” [5]

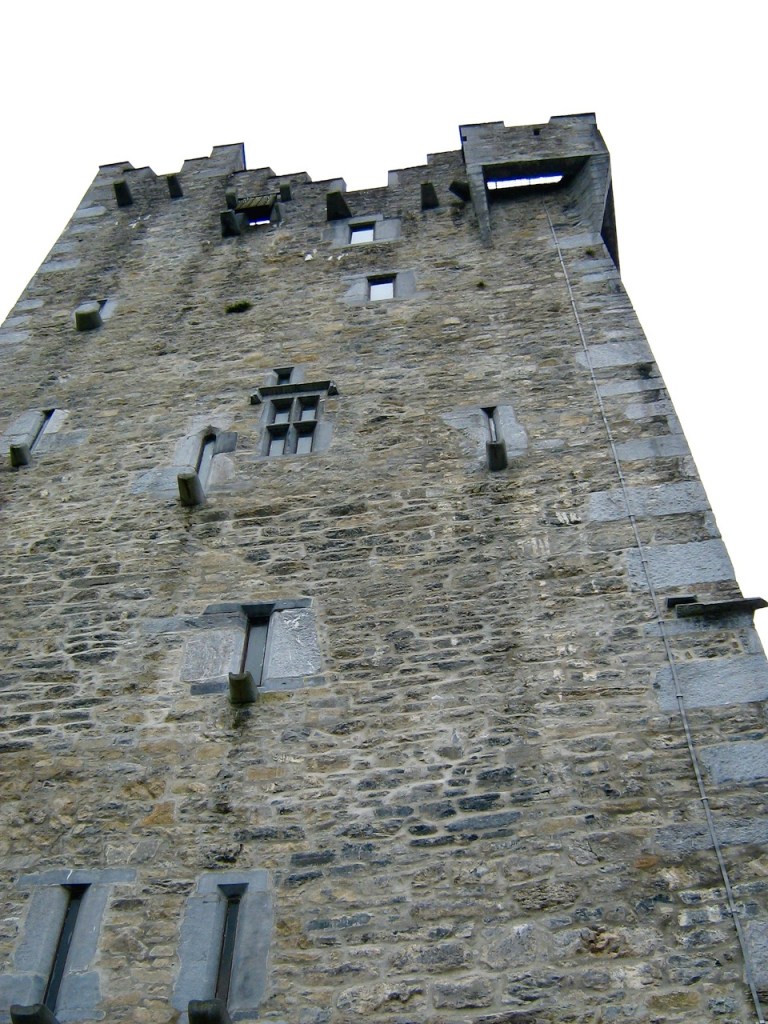

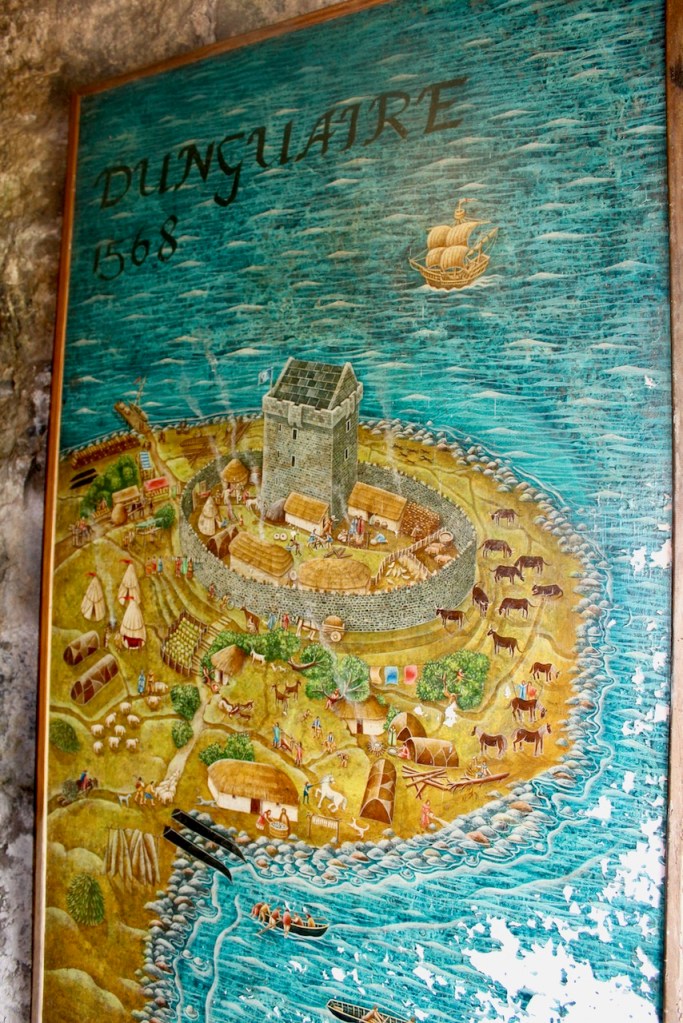

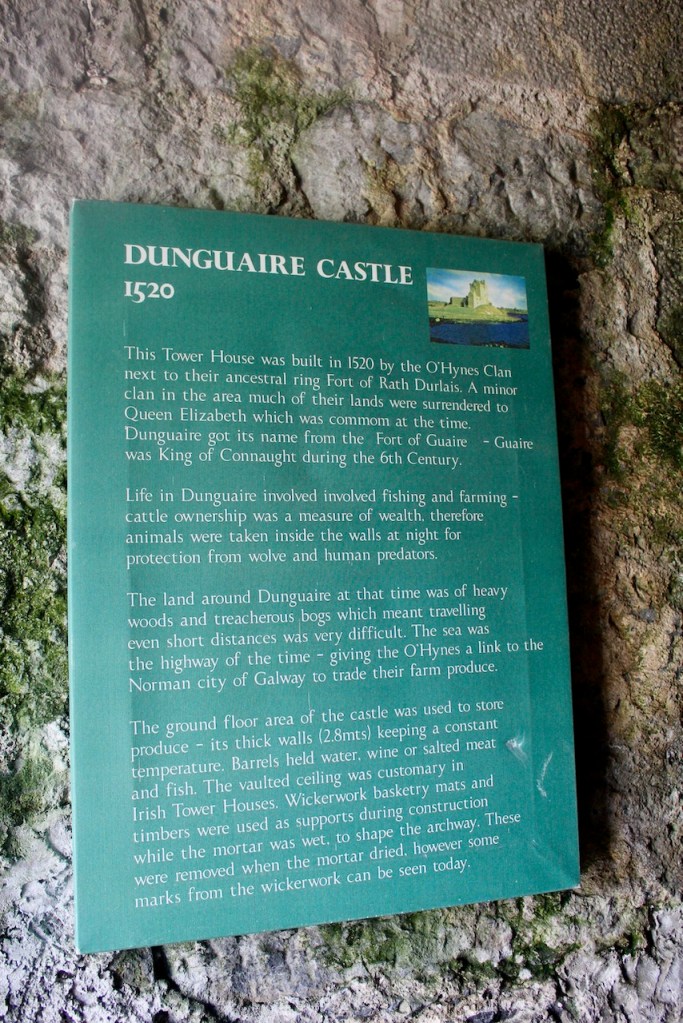

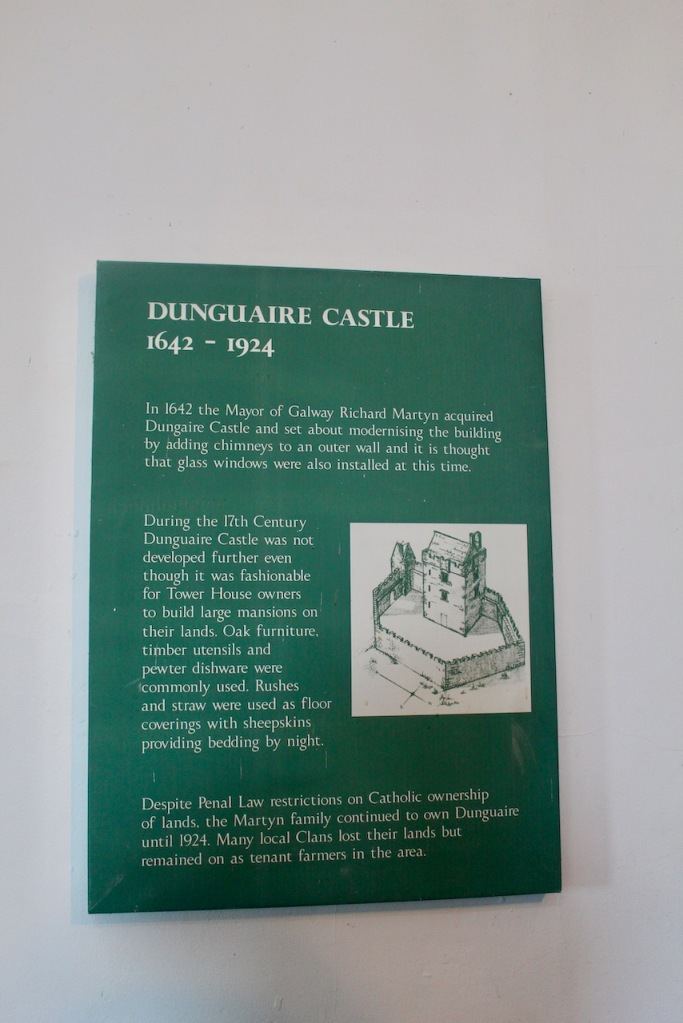

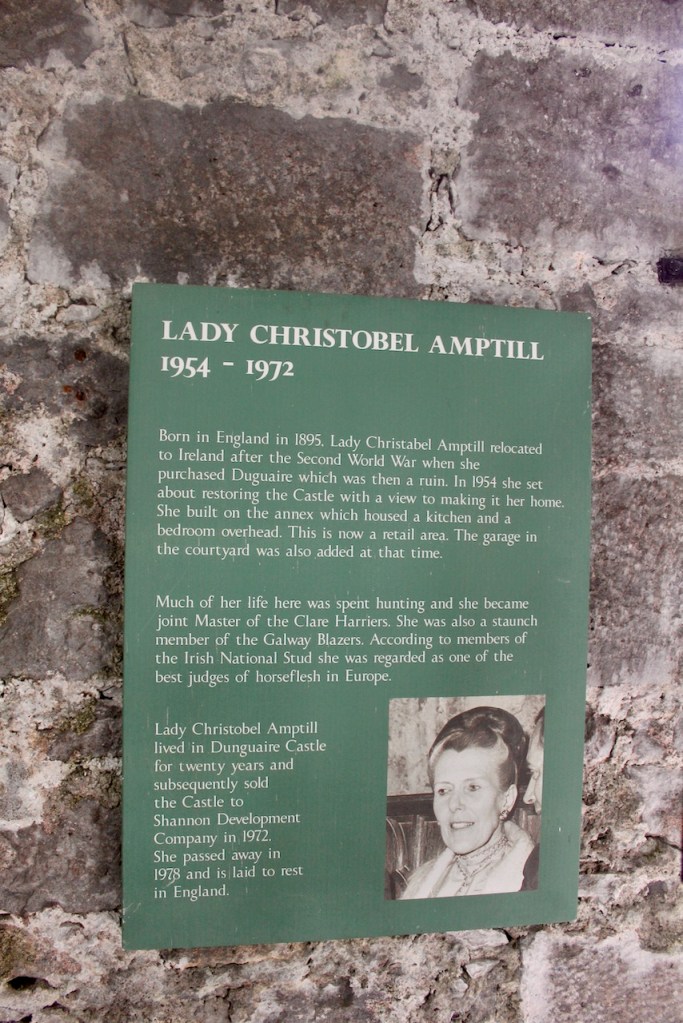

4. Dunguaire Castle, Kinvara, County Clare

Maintained by Shannon Heritage.

Mark Bence-Jones writes in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 115. “(Martyn/LGI1912; Gogarty/IFR; Russell, Ampthill, B/PB) An old tower-house with a bawn and a smaller tower, on a creek of Galway Bay; which was for long roofless, though in other respects well maintained by the Martyn family, of Tulira, who owned it C18 and C19, and which was bought in the present century by Oliver St John Gogarty, the surgeon, writer and wit, to save it from threat of demolition. More recently, it was bought by the late Christabel, Lady Ampthill, and restored by her as her home; her architect, being Donal O’Neill Flanagan, who carried out a most successful and sympathetic restoration. The only addition to the castle was an unobtrusive two storey wing joining the main tower to the smaller one. The main tower has two large vaulted rooms, one above the other, in its two lower storeys, which keep their original fireplaces; these were made into the dining room and drawing room. “Medieval” banquets and entertainments are now held here.”

5. Kilrush House, County Clare – Vandeleur Gardens

– ‘lost’, Vandeleur Gardens open

Timothy William Ferrers writes about it on his website:

“KILRUSH HOUSE, County Clare, was an early Georgian house of 1808.

“From 1881 until Kilrush House was burnt in 1897, Hector Stewart Vandeleur lived mainly in London and only spent short periods each year in Kilrush. Indeed during the years 1886-90, which coincided with the period of the greatest number of evictions from the Vandeleur estate, he does not appear to have visited Kilrush.

“In 1889, Hector bought Cahircon House and then it was only a matter of time before the Vandeleurs moved to Cahircon as, in 1896, they were organising shooting parties at Kilrush House and also at the Cahircon demesne.

“Hector Stewart Vandeleur was the last of the Vandeleurs to be buried at Kilrush in the family mausoleum. Cahircon House was sold in 1920, ending the Kilrush Vandeleurs’ direct association with County Clare. Hector Vandeleur had, by 1908, agreed to sell the Vandeleur estate to the tenants for approximately twenty years’ rent, and the majority of the estate was purchased by these tenants.

“THE VANDELEURS, as landlords, lost lands during the Land Acts and the family moved to Cahircon, near Kildysart.

“In 1897, Kilrush House was badly damaged by fire.

“During the Irish Land Commission of the 1920s, the Department of Forestry took over the estate, planted trees in the demesne and under their direction the remains of the house were removed in 1973, following an accident in the ruins.Today the top car park is laid over the site of the house.

“Vandeleur Walled Garden now forms a small part of the former Kilrush demesne. The Kilrush demesne was purchased by the Irish Department of Agriculture as trustee under the Irish Land Acts solely for the purpose of forestry. The Kilrush Committee for Urban Affairs purchased the Fair Green and Market House.” [6]

6. Knappogue or Knoppogue Castle, County Clare

Knappogue is maintained by Shannon Heritage and holds Medieval style banquets. https://www.knappoguecastle.ie

Mark Bence-Jones writes about Knoppogue, or Knappogue, Castle in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 180. “(Butler, Dunboyne, B/PB) A large tower-house with a low C19 castellated range, possibly by James Pain, built onto it. Recently restored and now used for “medieval banquets” similar to those at Bunratty Castle, Co Clare.”

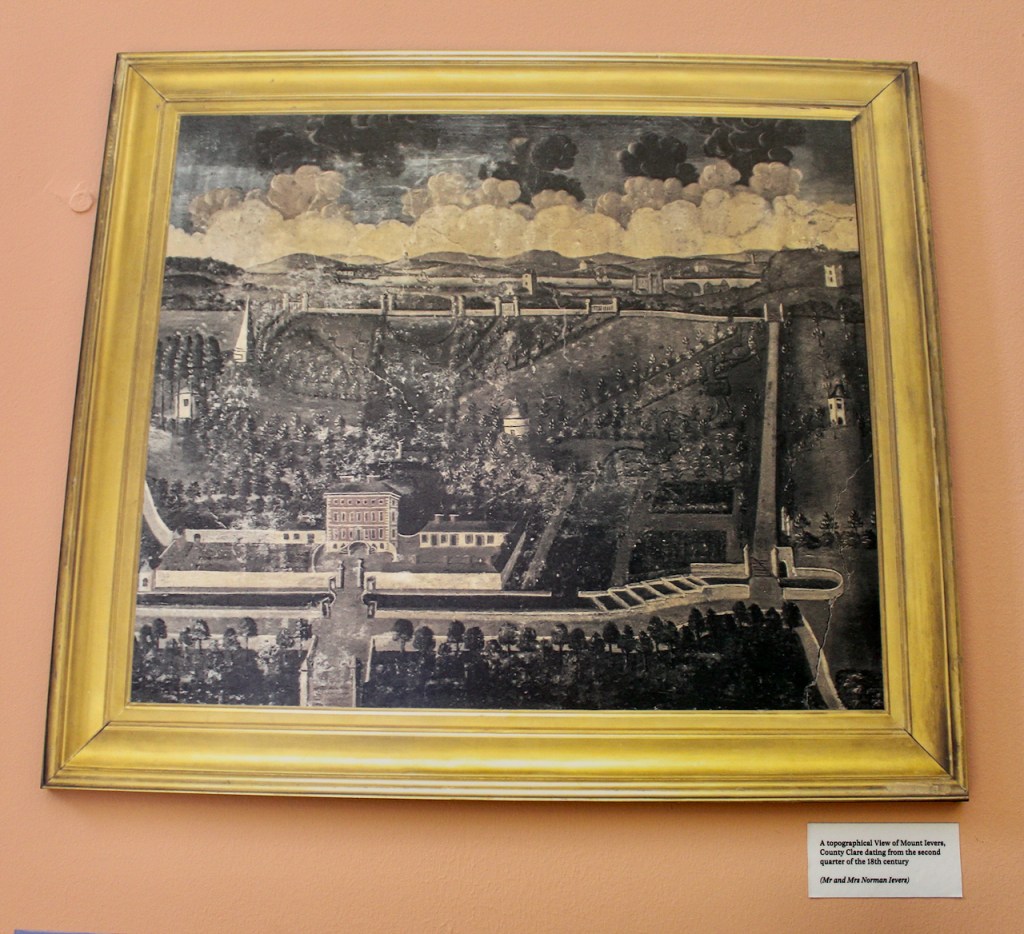

7. Mount Ievers Court, Sixmilebridge, County Clare

The website has a terrific history of the house. First, it tells us:

“Mount Ievers Court is an 18th c. Irish Georgian country house nestled in the Co. Clare countryside just outside the town of Sixmilebridge. The house was originally the site of a 16th c. tower house called Ballyarilla Castle built by Lochlann McNamara. The tower house was demolished in the early 18th c. to construct the present house, built between 1733-1737 by John & Isaac Rothery, for Col. Henry Ievers.

“Mount Ievers Court has been home to the Ievers family for 281 years and since then generations of Ievers and their families have worked hard to maintain the house in order to ensure that the estate retains a viable place in the local community and Ireland’s heritage long into the future. Mount Ievers is currently owned by Breda Ievers née O’Halloran, a native of Sixmilebridge, and her son Norman. Norman is married to Karen, an American by birth, who has a keen interest in Irish history & the family archives.“

Mark Bence-Jones writes in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 214. “(Ievers/IFR) The most perfect and also probably the earliest of the tall Irish houses; built ca. 1730-37 by Colonel Henry Ievers to the design of John Rothery, whose son, Isaac, completed the work after his death and who appears to have also been assisted by another member of the Rothery family, Jemmy. The house, which replaced an old castle, is thought to have been inspired by Chevening, in Kent – now the country house of the Prince of Wales – with which Ievers could have been familiar not only through the illustration in Vitruvius Britannicus, but also because he may have been connected with the family which owned Chevening in C17. Mount Ievers, however, differs from Chevening both in detail and proportions; and it is as Irish as Chevening is English. Its two three storey seven bay fronts – which are almost identical except that one is of faded pink brick with a high basement whereas the other is of silvery limestone ashlar with the basement hidden by a grass bank – have that dreamlike, melancholy air which all the best tall C18 Irish houses have. There is a nice balance between window and wall, and a subtle effect is produced by making each storey a few inches narrower than that below it. The high-pitched roof is on a bold cornice; there are quoins, string-courses and shouldered window surrounds; the doorcase on each front has an entablature on console brackets. The interior of the house is fairly simple. Some of the rooms have contemporary panelling; one of them has a delightful primitive overmantel painting showing the house as it was originally, with an elaborate formal layout which has largely disappeared. A staircase of fine joinery with alternate barley-sugar and fluted balusters leads up to a large bedroom landing, with a modillion cornice and a ceiling of geometrical panels. On the top foor is a long gallery, a feature which seems to hark back to the C17 or C16, for it is found in hardly any other C18 Irish country houses; the closest counterpart was the Long Room in Bowen’s Court, County Cork. The present owners, S.Ldr N.L. Ievers, has carried out much restoration work and various improvements, including the placement of original thick glazing bars in some of the windows which had been given thin late-Georgain astragals ca. 1850; and the making of two ponds on the site of those in C18 layout. He and Mrs Ievers have recently opened the home to paying guests in order to meet the cost of upkeep.”

The website tells of the ancient origins of the family, and goes on to explain:

“A parchment found in the sideboard at Mount Ievers in July 2012 maintains that Henry Ivers arrived in Ireland in 1640 from Yorkshire, where the family had been settled since arriving with William the Conqueror nearly six hundred years earlier. It also records that Henry settled in County Clare in 1643 when he was appointed Collector of Revenue for Clare and Galway.“

8. Newtown Castle, Newtown, Ballyvaughan, Co. Clare – section 482

www.newtowncastle.com ,

Open dates in 2025: Jan 6-Dec 19 Mon-Fri, National Heritage Week 16-24, 10am-5pm

Fee: Free

The website tells us: “The historic Newtown Castle has occupied a prominent position in Ballyvaughan since the 16th century. Having lain derelict for many years, the castle’s restoration began in 1994, completed in time for the opening of the Burren College of Art in August of that year.

“Newtown Castle is once again a vibrant building in daily use, central to the artistic, cultural and educational life of the Burren. It is open free of charge to the public on week days. Newtown Castle is also available to hire for: wedding ceremonies, small private functions or company events.”

Maurice Craig and Desmond Fitzgerald the Knight of Glin describe it in their book Ireland Observed. A handbook to the Buildings and Antiquities: “This sixteenth-century tower, nearly round in plan, rises from a square base, on which is the entrance door. Ingeniously places shot-holes protect its four sides.” [7]

Maurice Craig also writes about Newtown in his book The Architecture of Ireland from the Earliest Times to 1880:

“There is a small class of cylindrical tower-houses: so small that it is worth attempting to enumerate them all, omitting those which appear to be thirteenth-century (and hence not tower-houses). They are Cloughoughter, County Cavan (which is dubiously claimed for the fourteenth century); Carrigabrack, East of Fermoy County Cork; Knockagh near Templemore County Tipperary; Ballysheeda near Cappawhite County Tipperary; Golden in the same county; Crannagh now attached to an eighteenth century house near Templetuohy in the same county; Balief County Kilkenny; Grantstown near Rathdowney County Leix; Barrow Harbour County Kerry; Newtown near Gort in County Galway; Doonagore County Clare also by the sea; Faunarooska, Burren, County Clare; and Newtown at the North edge of the Burren, also in County Clare.

“The last of these is in some ways the most interesting, being in form a cylinder impaled upon a pyramid. Over the door (which is in the pyramid) there is a notch in the elliptical curve traced by the cylinder, and in this notch is a gunhole covering a wide sector of the sloping wall below. At some other castles, for example, Ballynamona on the Awbeg river, there is a feature using the same principle, which is not easy to describe. On each face of the building there is what looks at first site like the “ghost” or creasing of a pitched roof, but is in fact a triangular plane, about a foot deep at the top, decreasing to nothing at the base. In the apex there is a gunhole. Aesthetically the effect is very subtle.” [8]

9. O’Dea’s, or Dysert Castle, County Clare

– can visit https://dysertcastle.ie

The Castle was built in 1480 by Diarmuid O’Dea, Lord of Cineal Fearmaic. The uppermost floors and staircase were badly damaged by the Cromwellians in 1651. Repaired and opened in 1986, the castle houses an extensive museum, an audio visual presentation and various exhibitions.

Free car/coach parking and toilets

Tea rooms and bookshop

Chapel

Modern History Room 1700AD – 2000AD

Museum – Local artefacts 1000BC – 1700AD

Audio – visual presentation – local archaeology

Medieval masons and carpenters workshop

Roof wall – walk to view surrounding monuments

Places to Stay, County Clare

1. Armada House, formerly Spanish Point House, Spanish Point, County Clare €

The is a Victorian house, originally called Sea View House.

The website tells us:

“In 1884 the local Roman Catholic Bishop, James Ryan, expressed a wish to start a primary and secondary school in Miltown Malbay, a short distance from Spanish Point House, but his vision was unrealised for many years to come.

“In 1903 the bishop’s estate donated £900 to the Mercy Sisters to establish a school, but things did not happen until 1928, when three houses owned by the Morony estate were offered for sale to the Mercy Sisters with the intention of establishing a school at Spanish Point. The Moronys were a family of local landlords who had owned a significant number of properties in the Spanish Point and Miltown Malbay area between 1750 and 1929, including Sea View House, Miltown House, and The Atlantic Hotel.

“The Moronys were responsible for much of the development of the locality of Spanish Point, which began in 1712 when Thomas Morony took a lease of land, later purchased by his eldest son, Edmund, divided it into two farms and leased it to two local landlords for thirty-one years. Francis Gould Morony willed Sea View House, which he built in 1830, to his wife’s niece, Marianne Harriet Stoney, who married Captain Robert Ellis. The house was inherited by the Ellis family and one of their sons – Thomas Gould Ellis – became the son and heir.

“Almost a century later, in January 1928, a successor, Robert Gould Ellis, sold the property to the Mercy Sisters for £2,400 and in 1929 Colonel Burdett Morony sold Woodbine Cottage to the nuns for £300. Colonel Burdett Morony was a son of widow Ellen Burdett Morony of Miltown House, a woman who was quite unpopular amongst her tenants for rack-renting to such an extent that a boycott was operated against her. Woodbine Cottage, now part of the local secondary school building, was a summer residence of the Russell family and part of the Morony estate.

“On 19 March 1929 – the feast of St Joseph – a deed of purchase was signed and Sea View House became St Joseph’s Convent. The coach house, stables and harness rooms were fitted out as classrooms and a secondary school was opened on 4 September 1929.

“In 1931 the west wing was used as dormitories for boarders for the first time. In 1946 Wooodbine Cottage was converted into three classrooms and Miltown House (the Morony family seat, built in the early 1780s by Thomas J. Morony, who developed the town of Miltown Malbay) was also bought by the nuns and became the convent of the Immaculate Conception and a day school, while St Joseph’s was given over to boarding pupils.

“In 1959 a new secondary school was opened in part of Miltown House and in Woodbine Cottage by Dr Patrick Hillery, then Minister for Education. He originally came from Spanish Point and was later to become President of Ireland.

“In 1978 the boarding school at St Joseph’s closed, due to falling numbers, following the introduction of free secondary education and free school transport, which allowed pupils a greater choice of schools. The house was then given by the sisters to Clare Social Services as a holiday home for children, and was called McCauley House after the Venerable Catherine McCauley – founder of the Mercy Order.

“In September 2015 Clare Social Service sold the former convent to Pat and Aoife O’Malley, who restored it as a luxury guesthouse and re-named it Spanish Point House.”

2. Ballinalacken Castle (house next to), Lisdoonvarna, Co Clare – hotel €€

https://www.ballinalackencastle.com/

The website tells us that the property has been in the O’Callaghan family for three generations, and is now run by Declan and Cecilia O’Callaghan. The rooms look luxurious, some with four poster beds, and the hotel has a full restaurant.

The website tells us: “The original house was owned by the famous O’Brien clan – a royal and noble dynasty who were descendants of the High King of Ireland, Brian Ború. The house , castle and 100 acres of land was bought by Declan’s grandfather Daniel O’Callaghan, in 1938 and he and his wife Maisie opened it as a fine hotel. It was later passed to Daniel’s son Dennis and his wife Mary and then to his son, Declan. Declan and Cecilia have three children who also assist in the family business.“

“Standing tall on a limestone outcrop, our very own Castle, Ballinalacken Castle, is a two-stage tower house which was built in the 15th or early 16th century. It is thought the name comes from the Irish Baile na leachan (which means “town of the flagstones/tombstones/stones”).

10th Century: The original fortress is built by famous Irish clan, the O’Connors – rulers of West Corcomroe.

14th Century: The fortress itself is found and Lochlan MacCon O’Connor is in charge of its rebuilding.

1564: Control of West Corcomroe passes to Donal O’Brien of the O’Brien family.

1582: The lands are formally granted by deed to Turlough O’Brien of Ennistymon. After the Cromwellians triumphed in the area, five of Turlough’s castles are razed to the ground – but Ballinalacken is saved as it was not on the list of “overthrowing and demolishing castles in Connaught and Clare.”

1662: Daniel dies and grandson Donough is listed as rightful holder of the Castle.

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 26. “(O’Brien/LGI1912) A single-storey house with a curved bow, close to an old keep on a rock. The seat of the O’Brien family, of which Lord Chief Justice Peter O’Brien, Lord O’Brien of Kilfenora (known irreverently as “Pether the Packer”) was a younger son.”

3. The Carriage Houses, Beechpark House, Bunratty, County Clare € https://beechparkcountryhouse.ie

“A warm welcome awaits you at The Carriage Houses, situated in the grounds of Beechpark House, Bunratty, in the heart of County Clare on the west coast of Ireland.

“Part of the estate of a former Bishop’s Palace, the Carriage Houses have been restored to provide a retreat away from the frenetic pace of the modern world. We invite you to relax in your own luxury suite, complete with all modern amenities, and succumb to a slower pace of life while you are with us.”

4. Clare Ecolodge, formerly Loughnane’s, Main Street, Feakle, Co Clare

www.clareecolodge.ie

Open dates in 2025: June 1-August 31, Wed-Sun, Aug 16-24, 2pm-6pm Fee: Free

The website tells us:

“Clare Ecolodge at Loughnane’s, Feakle, in the heart of East Clare, is a unique family-run guest accommodation experience. We also offer group and self-catering accommodation as well as residential courses.

The buildings, which have been in the family for over 100 years, were renovated 10 years ago. Since then we have been welcoming guests from all over the world.

Clare Ecolodge at Loughnane’s offers a wide variety of accommodation to suit the needs of individuals and groups visiting Feakle for a residential courses or using the village as a base to explore the wild and beautiful landscape of County Clare.

Feakle is an ideal location from which to discover the East Clare countryside. Steeped in history and heritage, the area is known for its fine walks, stunning lakes, rugged mountains and of course its vibrant Irish traditional music scene.

Loughnane’s offers a unique blend of tranquillity and fun giving guests a genuine Irish experience.

“Clare Ecolodge at Loughnane’s in Feakle has been designated by the Irish State as a building of significant historical, architectural interest and members of the public are invited to view the building (free of charge) at the following times from June 1 to August 31 from Wednesday to Sunday between 2pm and 6pm.

Clare Ecolodge; The Energy Story:

“Clare Ecolodge was created in 2018 to signify the changes which we have implemented over the past two years at Loughnane’s Guesthouse/ Hostel. We have converted all our rooms in the main house to large private double and family rooms. In May 2018 we installed 30 Solar Photovoltaic (PV) panels on the roof of the main building. Look up and see for yourself! Since then we have been producing between 20 to 60kw hours per day.

“In May 2018 we also installed an air to water heat pump system. This is a low usage eco-water heating system powered by electricity. This heats all our water requirements for showers, laundry and kitchen requirements. We have not turned on our oil burner since installation. The average yearly energy requirements for an Irish household is approximately 4000kwh. Our energy system has produced this in the past 3 months. In that time we have avoided 2.5 tonnes of CO2. We use between 5 and 15kwh per day. The surplus is sent back to the grid at the transformer at the top of the village. We currently receive zero compensation for the excess electricity we generate but the ESB charges the community for the usage of this electricity.

“We estimate that we are currently at least 50% off-gird. Our main hot water and energy requirements are in the summer months. In high season there are more showers used and laundry needed. Our current energy system can handle this with little effort.

“For the past decade we have been growing our own vegetables and herbs for use in our kitchen.

Next phase – Winter time

“Our Solar PV panels are powered by light rather than heat so will work in winter, albeit not for periods as long in the summer. We aim to install a battery storage system so we can manage the energy we generate to be used at the most opportune times. We aim to install a second heat pump for our central heating requirements. This will effectively reduce our oil consumption to zero. We aim to install a wind turbine system on our 12 acre farm behind the main house. This will be used as a back up to bridge the energy generation gap between winter and summer.“

5. Dromoland Castle, Newmarket-on-Fergus, Co. Clare – hotel €€€

Mark Bence-Jones writes in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

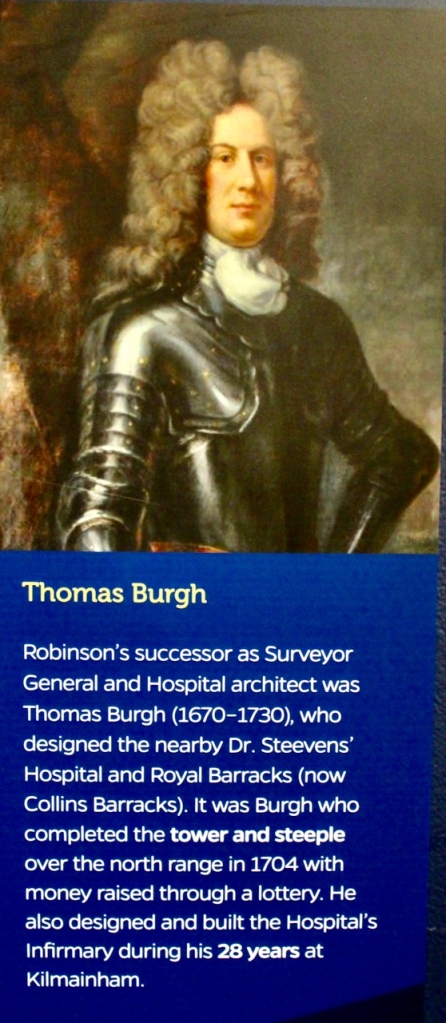

p. 109. “(O’Brien, Inchiquin, B/PB) Originally a large early C18 house with a pediment and a high pitched roof; built for Sir Edward O’Brien, 2nd Bt; possibly inspired by Thomas Burgh, MP, Engineer and Surveyor-General for Ireland. Elaborate formal garden. This house was demolished ca 1826 by Sir Edward O’Brien, 4th Bt (whose son succeeded his kinsman as 13th Lord Inchiquin and senior descendant of the O’Brien High Kings) and a wide-spreading and dramatic castle by James and George Richard Pain was built in its place. The castle is dominated by a tall round corner tower and a square tower, both of then heavily battlemented and machicolated; there are lesser towers and a turreted porch. The windows in the principal fronts are rectangular, with Gothic tracery. The interior plan is rather similar to that of Mitchelstown Castle, Co Cork, also by the Pains; a square entrance hall opens into a long single-storey inner hall like a gallery, with the staircase at its far end and the principal reception rooms on one side of it. But whereas Mitchelstown rooms had elaborate plaster Gothic vaulting, those at Dromoland had plain flat ceilings with simple Gothic or Tudor-Revival cornices. The dining room has a dado of Gothic panelling. The drawing room was formerly known as the Keightley Room, since it contained many of the magnificent C17 portraits which came to the O’Brien family through the marriage of Lucius O’Brien, MP [1675-1717], to Catherine Keightley, whose maternal grandfather was Edward Hyde, the great Earl of Clarendon. The other Keightley portraits hung in the long gallery, which runs from the head of the staircase, above the inner hall. Part of the C18 garden layout survives, including a gazebo and a Doric rotunda. In the walled garden in a C17 gateway brought from Lemeneagh Castle, which was the principal seat of this branch of the O’Briens until they abandoned it in favour of Dromoland. The Young Irelander leader, William Smith O’Brien, a brother of the 13th Lord Inchiquin, was born in Dromoland in C18 house. Dromolond castle is now a hotel, having been sold 1962 by 16th Lord Inchiquin, who built himself a modern house in the grounds to the design of Mr Donal O’Neill Flanagan; it is in a pleasantly simple Georgian style.”

Lucius Henry O’Brien, 3rd Baronet of Dromoland, County Clare (1731-95) also lived in 14 Henrietta St from 1767-1795 – for more about him, see Melanie Hayes, The Best Address in Town: Henrietta Street, Dublin and its First Residents 1720-80, published by Four Courts Press, Dublin 8, 2020.

6. Falls Hotel, formerly Ennistymon House, Ennistymon, Co. Clare €€

Mark Bence-Jones writes in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 121. “(Macnamara/IFR) :A two storey seven bay gable-ended C18 house with a two bay return prolonged by a single-storey C19 wing ending in a gable. One bay pedimented breakfront with fanlighted tripartite doorway; lunette window in pediment. Some interior plasterwork, including a frieze incorporating an arm embowed brandishing a sword – the O’Brien crest – in the hall. Conservatory with art-nouveau metalwork; garden with flights of steps going down to the river. The home of Francis MacNamara, a well-known bohemian character who was the father-in-law of Dylan Thomas and who married, as his second wife, the sister of Augustus John’s Dorelia; he and John are the Two Flamboyant Fathers in the book of that name by his daughter, Nicolette Shephard.”

7. Gregan’s Castle Hotel, County Clare €€€

The National Inventory tells us Gregan’s Castle was built in 1750. It tells us Gregan’s Castle is a: “six-bay two-storey house, built c. 1750, with half-octagonal lower projection. Extended c. 1840, with single-bay two-storey gabled projecting bay and single-storey flat-roofed projecting bay to front. Seven-bay two-storey wing with single-storey canted bay windows to ground floor, added c. 1990, to accommodate use as hotel.”

The website tells us:

“Welcome to Gregans Castle Hotel. Please take a look around our luxury, eco and gourmet retreat, nestled in the heart of the beautiful Burren on Ireland’s west coast. The house has been welcoming guests since the 1940s and our family have been running it since 1976. Our stunning 18th century manor house is set in its own established and lovingly-attended gardens on the Wild Atlantic Way, and has spectacular views that stretch across the Burren hills to Galway Bay.

“Inside, you’ll find welcoming open fires, candlelight and striking decoration ranging from modern art, to antique furniture, to pretty garden flowers adorning the rooms. Gregans Castle has long been a source of inspiration for its visitors.

“Guests have included J.R.R Tolkien, who’s said to have been influenced by the Burren when writing The Lord of the Rings, as well as other revered artists and writers such as Seamus Heaney and Sean Scully.

“And for the guests of today: with warm Irish hospitality, stylish accommodation, outstanding service and exceptional fine dining in our award-winning restaurant, we truly are a country house of the 21st century. You can do nothing or everything here. And whatever you choose, we’d like you to join us in celebrating all that is wondrous and beautiful in this truly exceptional place.“

Simon Haden and Frederieke McMurray

8. Loop Head Lightkeeper’s Cottage, County Clare €€ for 2; € for 4-6

https://www.irishlandmark.com/properties/

“Perched proudly on an enclosure at the tip of Loop Head stands the lighthouse station. Surrounded by birds and wild flowers, cliffs and Atlantic surf, Loop Head offers holiday accommodation with all of the spectacular appeal of the rugged west coast.“

9. Mount Callan House and Restaurant, Inagh, Co Clare – B&B

https://www.mountcallanhouse.ie

Culleen, Kilmaley,

County Clare, V95 NV0T

Mark Bence-Jones writes in A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 212. (Synge/IFR; Tottenham/IFR) A Victorian house of two storys over basement built 1873 by Lt Col G.C. Synge and his wife, Georgiana, who was also his first cousin, being the daughter of Lt-Col Charles Synge, the previous owner of the estate. The estate was afterwards inherited by Georgiana Synge’s nephew, Lt-Col F. St. L. Tottenham, who made a garden in which rhododendrons run riot and many rare and tender species flourish.”

The website tells us:

“Mount Callan House & Restaurant is situated in the beautiful surroundings of West Clare in the heart of Kilmaley village. We are a small, family-run restaurant, led by Chef Daniel Lynch, and guest house with a deep connection to our rural community.

“The local landscape is our inspiration and our food is created using the very best seasonal ingredients from award-winning, local suppliers.

“We encourage creativity, a good working environment and a community approach for the benefit of all.“

10. Mount Cashel Lodge, Kilmurry, Sixmilebridge, Co Clare – period self-catering accommodation €

and Stables https://hiddenireland.com/stay/self-catering-holiday-rentals/

The website describes it: “Enjoy luxury self-catering accommodation in these beautifully restored 18th Century lakeside lodges. Set in a 38 acre private landscaped estate with private Lake, riverside walk and Victorian cottage garden to explore. Lake boating, kayaking and fishing are available on site to complete this idyllic retreat.“

11. Newpark House, Ennis, County Clare €

https://www.newparkhouse.com/rates/

The website tells us: “Newpark House was built around 1750, and since then it has been the property of three families: the Hickmans, the Mahons and the Barrons.

“The Hickmans came into the possession of Cappahard Estate in 1733. On part of this estate, Gortlevane townland, Richard Hickman built a house and landscaped around it. Around this time he re-named the townland Newpark. Several of those trees from the planting of the new park still survive.

On his marriage in 1768 his father transferred the property to Richard. He died in 1810 and this property transferred to his son Edward Shadwell Hickman. Edward was a Crown Solicitor in Dublin and put the property up for rent.

“The Mahons: Patrick Mahon, a member of the new up and coming Catholic gentry, took up this offer and moved his family into Newpark. The Mahon family were very involved in the campaign for equal rights for Catholics in Ireland. Patrick’s son, James Patrick commonly known as The O’Gorman Mahon, nominated Daniel O’Connell to contest the famous Clare Election of 1828. O’Connell’s victory in this election resulted in the granting of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. It is highly likely that Daniel O’Connell stayed at Newpark during his visits to Ennis at this time. O’Gorman Mahon (1802-1891) had a very colourful life which ranged from hunting bears in Finland with a Russian Tzar to becoming a Colonel and Aide-de-Camp to the President of Costa Rica. Back in Ireland he is said to have introduced Parnell to Kitty O’Shea.

“While the Mahon family were living here they totally remodled the house. They added on wings and castlated the house in the Gothic revival style which was fashionable in Ireland at that time. The architect responsible would seem to be either John Nash or one of his former apprentices, the Pain brothers, all three were working in the area at this time.

“Of special historical significance is a pair of crosses on the turrets of the house. These crosses have shamrocks on the ends and were put there to commerate Catholic Emancipation. The Mahon family purchased the estate outright in 1853 and held it until 1904.

“At times when Newpark was owned by the Hickmans and Mahons several other families and individuals lived there. The Ennis poet Thomas Dermody spent time here with his father before he set off from Newpark, in 1785, for Dublin, in search of fame and fortune. Thomas remarked on the comfort he felt at Newpark during his time there. Also to have lived at Newpark were Captain William Cole Hamilton, a Magistrate (1870-1876), William Robert Prickett (1883-1886) and Philip Anthony Dwyer (1888-1904), Captains in the local Clare Division of the British Army.

“The Barrons: In 1904 the property came into ownership of the present family, the Barrons.

Timothy ‘Thady’ Barron was born on the side of the road, in 1847, during the famine. His father had lost his herdsman job, along with the herdsman’s cottage, due to a change of landlord. After a few tough years his father got another herdsmans job and Thady followed in his fathers footsteps. Thady moved in to Newpark in 1904 with his family and he lived he until his death in 1945. In the 1950s Thady’s son James ‘Amy’ bought the property from his sister Nance. In 1960 Amy’s son Earnan and his new wife Bernie moved into a barely habitable Newpark House. They set about slowly but surely bringing the house back to live. Luckily for them they got an opportunity to furnish the house with antiques, which were at that time considered second-hand furniture. Bernie opened up Newpark House as a B&B in 1966. Her son, Declan, is the present owner and we are looking forward to 50 years in business in 2016.”“The Barrons: In 1904 the property came into ownership of the present family, the Barrons.

Timothy ‘Thady’ Barron was born on the side of the road, in 1847, during the famine. His father had lost his herdsman job, along with the herdsman’s cottage, due to a change of landlord. After a few tough years his father got another herdsmans job and Thady followed in his fathers footsteps. Thady moved in to Newpark in 1904 with his family and he lived he until his death in 1945. In the 1950s Thady’s son James ‘Amy’ bought the property from his sister Nance. In 1960 Amy’s son Earnan and his new wife Bernie moved into a barely habitable Newpark House. They set about slowly but surely bringing the house back to live. Luckily for them they got an opportunity to furnish the house with antiques, which were at that time considered second-hand furniture. Bernie opened up Newpark House as a B&B in 1966. Her son, Declan, is the present owner and we are looking forward to 50 years in business in 2016.”

12. Smithstown Castle (or Ballynagowan), County Clare – tower house € for 4-8 for one week

From the website:

“Only few castles in the West of Ireland have survived into our times. Ballynagowan (Smithstown) Castle has played an exciting role in the history of North Clare, taking its name from ‘beal-atha-an-ghobhan’, meaning the ‘mouth of the smith’s ford’.

“It was first mentioned in 1551 when the last King of Munster, Murrough O’Brien, (also known as the Tanist, was created 1st Earl of Thomond and 1st Baron of Inchiquin in 1543), willed the Castle of Ballynagowan to his son Teige before his death.

“Over the years it accommodated many famous characters of Irish history. Records show that in 1600 the legendary Irish rebel “Red” Hugh O’Donnell rested there with his men during his attack on North Clare, spreading ruin everywhere and seeking revenge on the Earl of Thomond for his being in alliance with the English.

“In 1649 Oliver Cromwell’s army came from England with death and destruction. The Castle was attacked with cannons when Cromwell’s General, Ludlow, swept into North Clare striking terror everywhere he went.

“In 1650 Conor O’Brien of Lemeneagh became heir of the castle. His death, however, came shortly afterwards in 1551, as he was fatally wounded in a skirmish with Cromwellian troops commanded by General Ludlow at Inchicronan. With him had fought his wife Maire Rua O’Brien (“The Red Mary”, named after her long red hair), one of the best known characters in Irish tradition. She had lived in the castle as a young woman and it is the ferocity and cruelty attributed to her, which has kept her name alive. Legends tell that to save her children’s heritage after Conor’s death she married several English generals, who were killed in mysterious ways one after the other- she supposedly ended her bloody carrier entombed in a hollow tree.

“During 1652 almost all inhabitable castles in Clare including Smithstown were occupied by Cromwellian garrisons, a time of terrible uncertainty as Clare was under military rule.

“Over the next decades Ballynagowan Castle was the seat of army generals, the High Sheriff of County Clare and Viscount Powerscourt, one of the most powerful aristocrats who had their main residence – a monumental neogothic palace – in Dublin.

“The castle was last inhabited mid 19th century and until its recent restauration served as beloved meeting point for couples -, songs and poems about it finding their way into the local pubs.“

13. Strasburgh Manor coach houses, Inch, Ennis, County Clare €

https://www.strasburghmanor.com/about-strasburgh-manor/

The website tells us:

“The buildings that comprise the holiday homes were the coach houses attached to the House.

“Once occupied by James Burke, who was killed in the French Revolution in 1790, the House was named after the French town of Strasbourg.

“It figured prominently in Irish history up to its demise in 1921, when it was burned down during the Irish War of Independence.

“Families associated with it included: Burke, Daxon, Stacpoole, Huxley, Mahon, Talbot, Taylor, Scott & McGann (ref: ‘Houses of Clare’ by Hugh Weir, published by Ballinakella Press, Whitegate, Co. Clare).“

Whole House Rental, County Clare

1. Inchiquin House, Corofin, County Clare – whole house rental, €€€ for 2, € for 6-10

The website tells us “Inchiquin House is an elegant period home in County Clare, romantically tucked away in the west of Ireland not far from the Wild Atlantic Way. It is the perfect base from which to explore the unique Burren landscape, historic sites, and the region’s many leisure activities.“

2. Mount Vernon lodge, Co Clare – whole house accommodation € for 7-11 people

“Mount Vernon is a lovely Georgian Villa built in 1788 on the Burren coastline of County Clare with fine views over Galway Bay and the surrounding area.

“Built in 1788 for Colonel William Persse on his return from the American War of Independence, Mount Vernon was named to celebrate his friendship with George Washington. The three remaining cypress trees in the walled garden are thought to have been a gift from the President.

“During the nineteenth century Mount Vernon was the summer home of Lady Augusta Gregory of Coole, an accomplished playwright and folklorist and a pivotal figure in the Irish Cultural Renaissance. It was her collaboration with W.B.Yeats and Edward Martyn that created the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1904. Lady Gregory entertained many of the luminaries of the Irish Literary Revival at Mount Vernon including W.B.Yeats, AE (George Russell), O’Casey, Synge and George Bernard Shaw.

“In 1907 Lady Gregory gave the house to her son Robert Gregory as a wedding present and it was from here that he produced many of his fine paintings of the Burren landscape. He later joined the Royal Flying Corps and was shot down by ‘friendly fire’ in 1918, an event commemorated by W.B.Yeats in his famous poem, An Irish Airman Foresees his Death.

“A feature from this period are the unusual fireplaces designed and built by his close friend the pre-Raphaelite painter Augustus John.“

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] p. 49. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://www.irishhomesandgardens.ie/irish-architecture-history-part-1/

[5] https://www.geni.com/projects/Historic-Buildings-of-County-Clare/29203

[6] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com

[7] Craig, Maurice and Knight of Glin [Desmond Fitzgerald] Ireland Observed. A handbook to the Buildings and Antiquities. The Mercier Press, Dublin and Cork, 1970.

[8] p. 103. Craig, Maurice. The Architecture of Ireland from the Earliest Times to 1880, Lambay Books, Portrane, County Dublin, first published 1982, this edition 1997, p. 103.

[10] https://www.geni.com/projects/Historic-Buildings-of-County-Clare/29203

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com