A place providing group accommodation let me know that my “places to visit and stay” pages for each county can cause confusion, since places of accommodation are not necessarily ones you can visit. Therefore I am separating into pages of places to visit, and places to stay. I will be republishing these over the next few weeks.

Carlow:

Places to stay, County Carlow

1. Huntington Castle, County Carlow – B&B and self-catering

2. Kilgraney House, County Carlow – holiday rental courtyard and cottage suites

3. Killedmond Old Rectory, County Carlow – shepherd’s huts

4. Lisnavagh, County Carlow – holiday cottages and wedding venue

5. Lorum Old Rectory, Kilgreaney, Bagenalstown, County Carlow – B&B

6. Mount Wolseley, Tullow, Co Carlow – hotel

Group holiday rental or wedding venues in County Carlow

1. Ballykealey, Tullow, Co Carlow – wedding or event venue

2. Borris House, Borris, County Carlow – wedding venue

3. Lisnavagh, County Carlow – holiday cottages and wedding venue

4. Sandbrook, Tullow, Co Carlow – whole house rental and an apartment in house

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Carlow:

1. Huntington Castle, County Carlow – B&B in castle or self-catering in wing or gate lodge or cottage.

https://huntingtoncastle.com/all-rooms

Huntington Castle is on the Revenue Section 482 list so is open to the public on listed days. See my write-up:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2019/06/28/huntington-castle-county-carlow/

Postal address: Huntington Castle, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford

www.huntingtoncastle.com

Open dates in 2026, but check website as sometimes closed for special events: Jan 31, Feb 1, 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 28, Mar 1, 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 28-31, Apr 1-6, 11-12, 18-19, 25-26, May 1-31, June 1-30, July 1-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1-30, Oct 3-4, 10-11, 17-18, 24-31, Nov 1, 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 28-29, Dec 5-6, 12-13, 19-20, 11am-5pm

Fee: house and garden, adult €13.95, garden only €6.95, OAP/student, house and

garden €12.50, garden only €6, child, house and garden €6.50, garden €3.50, group

and family discounts available

2. Kilgraney House, County Carlow – holiday rental courtyard and cottage suites

“Kilgraney is a gracious Georgian country house with courtyard suites and cottages overlooking the Barrow valley. The property is less than ninety minutes by car from Dublin and is located halfway between Bagenalstown and Borris village. Kilgraney Courtyard Suites and Cottages are open for B & B packages from May to October 2022.

“Surrounded by extensive gardens and granite stone courtyards filled with culinary, aromatic and medicinal plants, the property offers guests a memorable country house experience in a tranquil rural setting on the Carlow Kilkenny border.

“Since 1994 we have been inspired by Kilgraney and captivated by what the surrounding countryside, towns and people have to offer. For the 2020 season we have decided to take a break from the kitchen and close our dining room. We will continue to offer our renowned breakfast and can recommend some very fine local restaurants.

“Through words and images we invite you to our home and we hope that they entice you to come and experience Kilgraney for yourself.

“At Kilgraney House we create a place of peace and tranquility and therefore we close the house at 1.00 am. If you wish to stay out later than this please book one of our courtyard suites, the garden cottage or the lodge.“

http://www.igp-web.com/Carlow/Kilgraney.htm

“The house is a charming late Georgian house, overlooking the Barrow valley, and is conveniently situated halfway between Kilkenny city and Carlow town. The house takes its name from the Irish ‘cill greine’ which means ‘sunny hill’ or ‘sunny wood’.

“Kilgraney (Kilgreaney ) has seen many changes over the centuries. The house, spelt Kylgrany, appears on Mercator’s Map of Carlow in 1595 and parts of the lower courtyard, reached through the kitchen garden, date to around this time. The main house was built around 1820 although the north wing is part of older dwelling and thought to be mid-18th century. A fire in the 1920’s destroyed the original interiors and the rebuilding left Kilgraney House with a Georgian exterior and a plain early 20th century interior. Now carefully restored, the house has immense character and a simple elegance that is full of irony and amusement. The lush interiors are an eclectic mix of traditional furniture with carefully chosen pieces of fabric, furniture and art from around the world.“

Source: Ireland’s Blue Book of Country Houses & Restaurants.

3. Old Rectory Killedmond, Borris, Co Carlow R95 N1K7 – section 482 with shepherd hut accommodation

https://www.blackstairsecotrails.ie/

The Old Rectory Killedmond is on the Revenue Section 482 list so can be visited on certain days. See my write-up:

https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/07/16/the-old-rectory-killedmond-borris-co-carlow/

https://www.blackstairsecotrails.ie/

Open dates in 2026: July 1-31, Aug 1-31, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student €6, child free.

4. Lisnavagh, County Carlow, wedding venue and holiday cottages

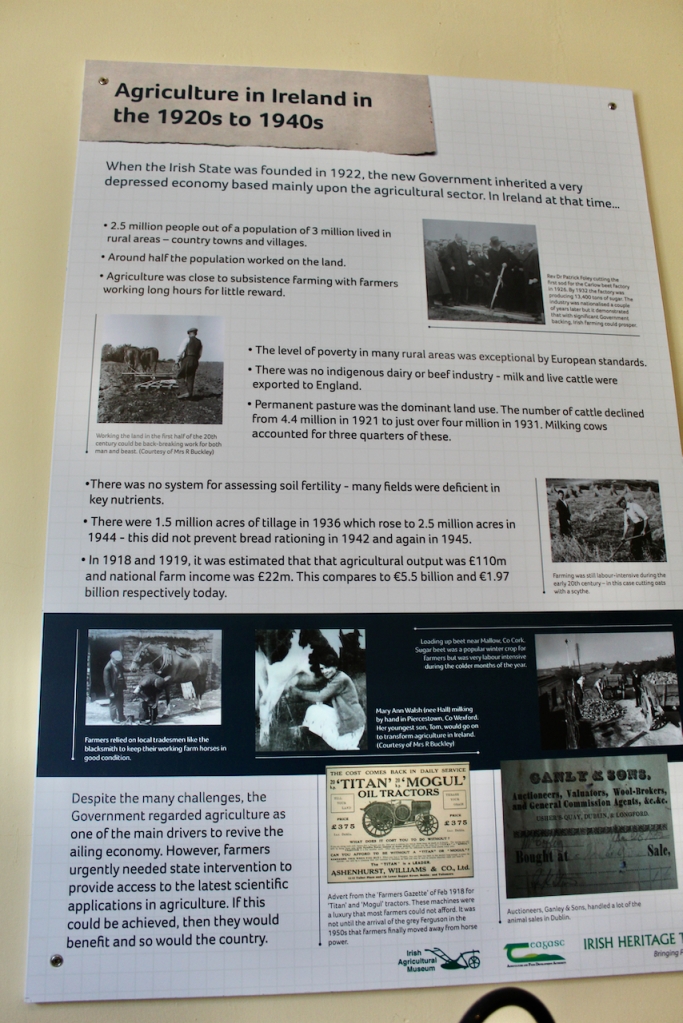

The National Inventory tells us that it was designed around 1847 by Daniel Robertson. It was built for William McClintock-Bunbury (1800-1866). Around 1953, it was truncated and reordered, to make it more liveable, and this was designed by Alan Hope.

Lisnavagh is a wedding venue, and there are buildings with accommodation, including the farm house, converted courtyard stables, the groom’s cottage, schoolhouse, farm and blacksmiths cottages and the bothy.

The website tells us that:

“The estate is owned by William & Emily McClintock Bunbury. Lisnavagh House & Gardens is managed by Emily and William along with a hardworking and dedicated team in both the house and the gardens.

“William McClintock Bunbury returned to Lisnavagh in 2000 with a view to creating a financially sustainable life and business on the estate. In 2001, The Lisnavagh Timber Project was established and during the following years parts of Lisnavagh Farmyard were refurbished into offices some of which now house the family enterprises.“

In his book about the Carlow Gentry, Jimmy O’Toole writes:

“The Bunbury wealth was considerably enhanced after the marriage of a later generation William Bunbury to Catherine Kane, daughter of Redmond Kane, a wealthy Dublin merchant in 1773. William [who lived at Moyle, County Carlow], who was elected MP for Carlow in 1776, was killed two years later when he was thrown from his horse in Leighlinbridge. It was the marriage of William and Catherine’s only daughter, Jane Bunbury to John McClintock, MP, of Drumcar, Co Louth, in 1797, that linked the Bunbury and McClintock names. It was their son John who was created Lord Rathdonnell on 21st Dec 1868. Their second son, William Bunbury-McClintock-Bunbury, born 1800, in compliance with the will of his maternal uncle Thomas Bunbury, MP, assumed the name of Bunbury in addition to that of McClintock. The McClintocks were an old Scottish family and the first to settle in Ireland was Alexander McClintock, who purchased the Rathdonnel estates in County Donegal in 1597, from where the title originated.” [7]

John McClintock married a second time, to Elizabeth Le Poer Trench, daughter of the 1st Earl Clancarty.

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

William Bunbury and Catherine Kane had two sons, Thomas and Kane. Jimmy O’Toole writes about these brothers (p. 66):

“The election of 1841, when Thomas Bunbury and his Tory colleague Henry Bruen II, defeated Daniel O’Connell Jr and John Ashton Yates, was one of the bitterest election contests every witnesses in County Carlow…. A bachelor, Thomas’s 6000 acre estate in the parishes of Kellistown, Rathmore and Rathvilly, passed to his brother Kane after his death.”

O’Toole continues:

“His seat in Parliament was taken by his nephew William McClintock-Bunbury [1800-1866, son of John McClintock and Jane Bunbury], who was returned unopposed, and held the seat for sixteen years with a brief interruption in 1852. William had served as a Captain with the Royal Navy during the 1820s and 1830s…After inheriting the family’s Carlow estates, he completed the building of Lisnavagh, a large and rambling Tudor-Revival house of granite, in 1847. The architect was John McGurdy. That year, William and his wife Pauline, daughter of Sir James Stronge of Tynan Abbey in Armagh, and their young family, moved from Louth to live at Lisnavagh.”

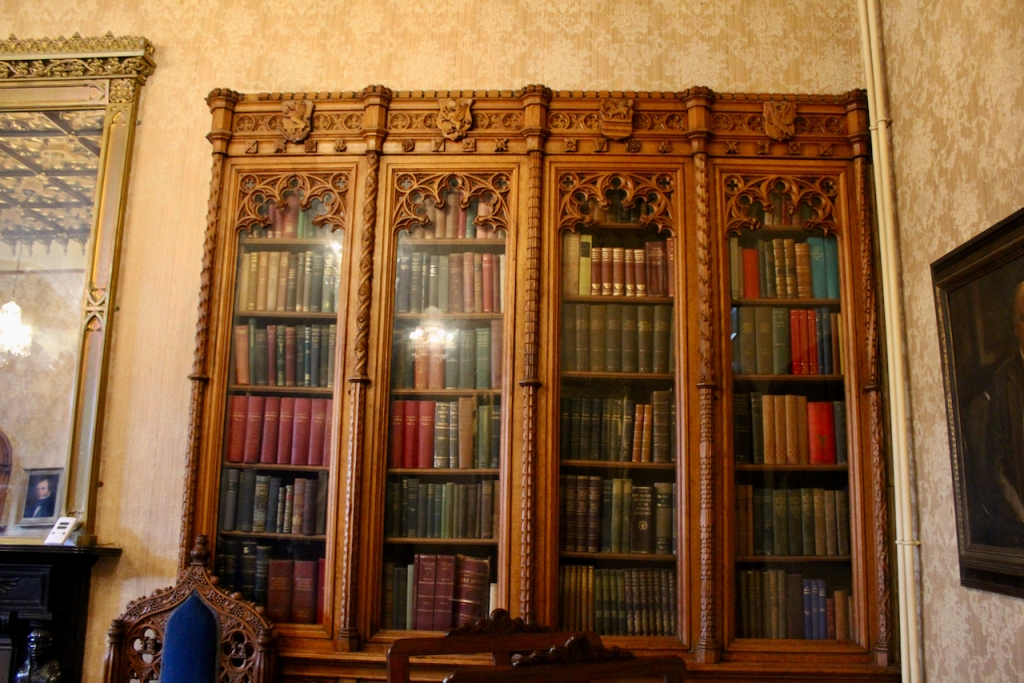

p. 187. “[Bunbury/LG1863; McClintock-Bunbury, Rathdonnell, B/PB] A large and rambling Tudor-Revival house of grey stone, built 1847 for William McClintock-Bunbury, MP, brother of 1st Lord Rathdonnell, to the design of John McCurdy. Many gables and mullioned windows; some oriels; but all very restrained, with little or no ornament and hardly any Gothic or Baronial touches apart from a porte-cochere on the service wing, which was set back from the main entrance front, and a loggia of segmental-pointed arches at the other side of the house. The port-cochere served the luggage entrance; the hall door having no such protection. Staircase of wood, ascending round large staircase hall. Drawing room with ceiling of ribs and bosses and marble chimneypiece in Louis Quinze style, en suite with library; richly carved oak bookcases. The house was greatly reduced in size ca. 1953 by 4th Lord Rathdonnell [William Robert McClintock-Bunbury (1914-1959) – with much help with his wife Pamela]; that part which contained the principal rooms being demolished, and the service wing being adapted to provide all the required accommodations. The porte-cochere, which comes in the middle of the entrance front of the reduced house, is now the main entrance. Because of the irregular plan of the house as it originally was, the service wing only abutted on the main building at one corner, which has been made good with a gable and oriel from the demolished part; so that the surviving part of the house looks complete in itself; a pleasant Tudor-Revival house of medium size rather than the rump of a larger house. A large library has been formed out of several small rooms; it is lined with the bookcases from the original library, and with oak panelling and Cordova leather of blue-green and dull bronze-gold. Fine baronial gate arch.”

The house remains in the family.

5. Lorum Old Rectory, Kilgreaney, Bagenalstown, Co. Carlow R21 RD45 – B&B

www.lorum.com

Tourist Accommodation Facility – not open to the public

Open for accommodation: April-October

The Irish Historic Houses Association website tells us:

“The valley of the River Barrow is particularly beautiful, especially downstream from Bagenalstown where the river, which forms the boundary between Counties Carlow and Wexford, flows along the western foothills of the Blackstairs Mountains. The Barrow passes through the towns of Borris and Graiguenamanagh and the village of St. Mullins, where the valley sides become increasingly steep. In the late 1850s Denis Pack-Beresford [1818-1881], a local landowner from nearby Fenagh, donated land for a new church and rectory at Lorum near Kilgreaney, a small hamlet overlooking the river under the shadow of Mount Leinster. ” [4]

Denis Pack took the name Beresford from his mother, Elizabeth Louisa Beresford who was a daughter of George De La Poer Beresford, 1st Marquess of Waterford, of Curraghmore.

The Irish Historic Houses continues: “Lorum is a restrained Gothic building of warm, golden Carlow granite and a fine example of a Victorian country rectory. Of two storeys, the principal fronts are all of three bays, with a studied asymmetry that falls just short of becoming symmetrical. There are many gables and the entrance is recessed beneath a wide gothic arch, which acts as a porch and helps to give the building a solid, comfortable appearance that embodies the religious certitudes of the Church of Ireland during the last years of establishment.

The interior is decorated in a mild and restrained Victorian Gothic; bright and airy, not too large or grand but solid and respectable. While Lorum may well have been built to the designs of Welland and Gillespie, there is little doubt that the dominant influence was the religious architecture of Augustus Welby Pugin.” (see [7])

William Joseph Welland and William Gillespie, the Dictionary of Irish Architects tells us, were appointed joint architects to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in May 1860, following the death of Joseph Welland. According to this dictionary, both men were already in the employment of the Commissioners, and they held the post until the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland on 31 December 1870. During their ten years in office, they developed an increasingly personal and idiosyncratic version of Gothic in the churches which they designed. They designed many churches, all over Ireland.

The Irish Historic Houses website tells us: “The first rector was the Revd. King Smith who was installed at Lorum in 1863 and the house continued in use as a rectory until 1957, when it was offered for sale by the parish and bought by Tennant Young, father of the present owner.” (see [4])

A Carlow county website tells us that:

“In the second half of the 20th century the Church of Ireland passed thorough a period of rationalisation. Parishes were amalgamated; churches closed and a number of rectories became redundant and were sold. Among these was Lorum Old Rectory which Mr. Young purchased as a home for his family. Fast forward for another thirty-five years and his daughter Bobbie, on inheriting the house, was forced to make it pay and, together with her late husband Don, decided to provide country house accommodation for visitors to the region.” [5]

The Irish Historic Houses website continues: “To the north is a small, enclosed stable yard with a coach house for the rector’s trap, a stable for his horse, and quarters for his groom and other servants. Today Lorum is unusual because both house and grounds have been so little altered, a fate shared by few other Irish rectories.” (see [4])

The National Inventory describes is as:

“Detached three-bay two-storey Tudor Revival former rectory with half-dormer attic, c. 1864, with mullioned window openings, gables and series of service wings. Now in use as guesthouse. Stable complex to rear with two-storey coach house.“

The Record of Protected Structures adds that the roof is high pitched, covered with natural slates, and has Victorian, earthenware chimney-pots and has wide eaves.

The Old Rectory Lorum website tells us:

“Lorum is a place known to a few – but in the 19th century, when the protestant church of Ireland enjoyed wealth and state patronage, it was the spiritual hub of a parish which included an exceedingly comfortable and spacious rectory. The clergy have departed and the rectory is now the property of Bobbie Smith, who provides guests with fantastic dinners in a dining room which retains its hint of 19th century opulence. Antique bedrooms with modern comforts provide for rest, to be followed by a most splendid breakfast. The lady of the house, incidentally, is a mine of information on Carlow and the organiser of bicycle tours in the region.“

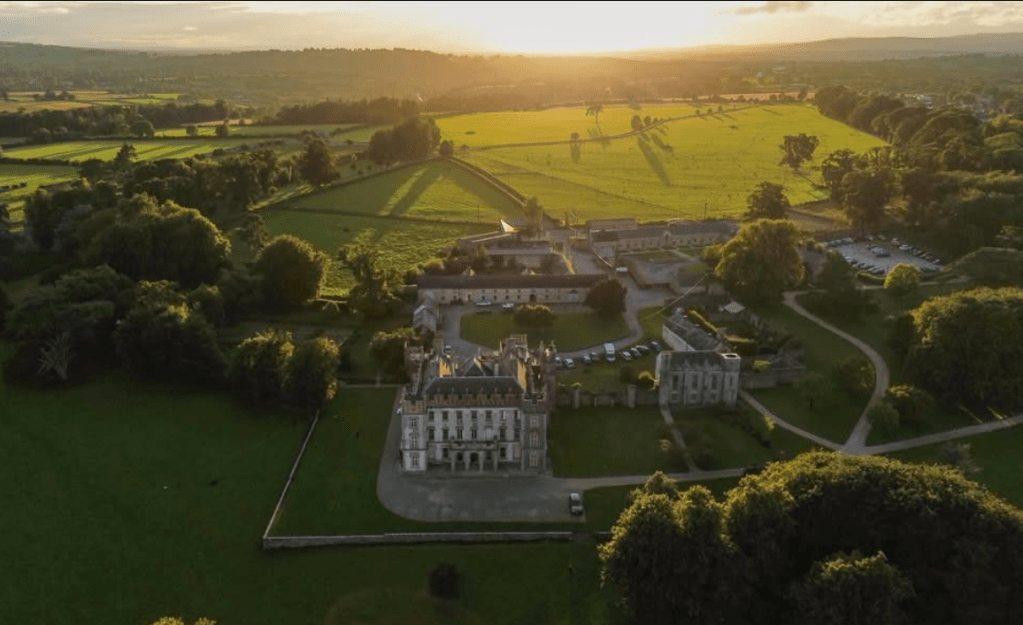

6. Mount Wolseley, Tullow, Co Carlow – hotel

The Record of Protected Structures describes Mount Wolseley:

“A three-bay, two-storey, Italianate house designed by the firm of Sir John Lanyon about 1870. It has painted, lined and rendered walls, a basement, raised coigns, string courses, an enclosed porch with a segmental-headed doorcase and side lights, windows with architraves, wide, bracketed eaves and a hipped roof with a pair of stacks. The sash windows have large panes of glass. On the left-hand side is a service wing. The house is well maintained and in use as a hotel.“

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 218. “(Wolseley, Bt, of Mount WolseleyPB) A two storey slightly Italianate Victorian house. Camber-headed windows; ornate balustraded porch; roof on bracket cornice. Wing with pyramidal roof. Now a school.”

Jimmy O’Toole tells us:

p. 211. “Richard Wolseley, from Staffordshire, was the first to settle in Tullow, where he inherited the irish estates of his father, also Richard. The elder Richard, who served with King William III in Ireland, was MP for the Borough of Carlow during the reign of Queen Anne (1703-1713). His son, who served as an MP for the Borough from 1727-1768 – a record continuous tenure of parliamentary representation – was created a Baronet in 1744. The family had 2,500 acres in Carlow and 2,600 acres in Co Wicklow. The Wolseleys, according to O’Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters, were the beneficiaries of land grants after the Cromwellian settlement, but his claim that Mount Arran was included is wrong. Mount Arran, purchased from Charles Butler, Earl of Arran, did not come into their possession until some time after 1725, because on 23 March that year, the second Duke of Ormonde leased the estate to Thomas Green of Rahera, Co Carlow. The original of this lease was presented at a meeting of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland earlier this century, by Fr. James Hughes of Maynooth.” [6]

The house was reconstructed by Sir Thomas Wolseley in 1864 and the estate was sold to the Patrician Order for £4,500 in 1925 by the daughters of Sir John Richard Wolseley. When Sir John died aged forty, he was succeeded in the title by his brother Sir Clement James Wolseley who was probably the last of the family to occupy Mount Wolseley.

In 1994 Mount Wolseley was purchased by the Morrissey family and has since been developed into a four star, quality hotel and 18-hole championship golf course with a range of activities on its doorstep offering guests plenty of things to do on their stay. [7]

Before it was owned by the Wolseleys, the area was called Mount Arran, and belonged to the Baggot family! It belonged to John Baggot. I have tried to research this history. John was father of Mark, who was a founding member of the Dublin Society, and who also owned much property around St. Michan’s and Smithfield. Their land deeds are in Carlow County Library. In John Ryan’s The History And Antiquities Of The County Of Carlow (1833) there is an abstract of convenyances from the Trustees of the Forfeited Estates in County Carlow in 1688:

“The estate of John Baggott, Esq., attainted; which having been granted 26th Feb., 1697, to Joost, Earl of Albemarle [Arnold Joost van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle (1670-1718) a Dutch military leader who fought for William III], were by him, by deeds of lease and release, dated 27th and 28th February, 1698, for the sum of three hundred pounds conveyed to Charles Balwin, of Dublin, Esq., in trust for Mark Baggott, Esq., to whom, by deeds of lease and release, dated 8th and 9th March, 1698, he conveyed the same in execution of the said trusts ; and the said Baggott, by indenture dated 22nd March, 1702, assigned and made over his interest and right of purchasing the premises from the trustees, for three hundred and five pounds ten shillings to said Ph. Savage. — Inrolled 8th April, 1703.”

There were complications over this transaction, as of course the land was not given up willingly! I believe John Baggot fought at the Seige of Limerick, and was present when the truce and Treaty were drawn up, stating that those holding the castle would stop their fighting if they were promised that their land would not be taken from them. Thus, John Baggot’s land should not have been forfeited, despite him being a Catholic. However, John Baggot died and his son Mark should have inherited the land in Carlow and Dublin. Mark’s Protestant neighbours protested, calling Mark Baggot a “violent Papist.”

“Mark Baggot of Mount Arran, Co. Carlow, inquisition of forfeited estate, Baggot produced a deed which settled land on Mark after the father’s death. Jury refused deed and land was granted to Abermarle, from John, but Mark disputed and won. Mark was in the article of Limerick but his father wasn’t. With the passing of the Act of Resumption the estate became vested in the trustees, and Mark accordingly lodged his claim. Before it came up for hearing, his father died, thus the admission of the claim would mean immediate restoration to Mark.

The case was contested, local feeling against Mark amongst Carlow Protestants, as he was called “a violent Papist,” son of John Baggot late of Mount Arran (according to Turtle Bunbury’s website, John Baggot was a Catholic soldier: John Baggot, a Catholic soldier, leased Tobinstown in 1683 from Benjamin Bunbury. Bagot was attainted for serving King James II and his Carlow estates were acquired in 1702 by Philip Savage.). Mark was High Sheriff of Carlow in 1689, “acted with pride against Protestants.“

When John Baggot was outlawed and his estate forfeited, Ormond “quite irregularly” gave fresh lease of Mount Arran to Richard Wolsley, the son of Brigadier William Wolsley. Richard Wolsley did not want to give the house up to Mark Baggot.

Mark had an ally in Bishop William King of Derry and later of Dublin, due to common interest in Maths and barometers! There are many of Baggot’s letters in King’s correspondence. Mark writes to him that “the gentleman who lives in my house..uses all his interest and power to hinder and delay.”

Mark Baggot lost his land at Mount Arran but inherited Shangarry, Ballinrush, Portrussian, in Carlow, and they were preserved in the family and descended to James John Bagot Esq. of Castle Bagot, Rathcoole, County Dublin, the last male of his name (from him they passed to his sister and her husband, Ambrose More O’Ferrall).

Group holiday rental or wedding and event venues in County Carlow

1. Ballykealey, Tullow, Co Carlow – wedding and event venue

and lodges: https://ballykealeyhouse.com

The website tells us

“The House is available for private hire for family gatherings, retreats or corporate events. Distinct character and warmth characterise the 12 individually appointed bedrooms in the manor house. All have gracious views of the surrounding countryside and retain all the original features of the 19th century house. All bedrooms have recently been renovated and include the modern comforts you would expect to find.” It has twelve rooms in the house and 15 self-catering lodges.

Mark Bence-Jones writes in his A Guide to Irish Country Houses (1988):

p. 23. “(Lecky/LGI1937 supp) A somewhat stylized Tudor-Revival house of stucco with stone facings, built ca 1830 for John James Lecky to the design of Thomas A. Cobden, of Carlow. Symmetrical front of two storeys and high attic, with three unusually steep gables ending in finials; recessed centre with three-light round-headed window edged with stonework in a rope pattern above a stone Gothic porch of three arches. Tall Tudor chimneystacks at either end; slender battlemented pinnacles rising from corbels at the angles of the roof parapet. Battlemented single storey wing at one side, prolonged by battlemented screen walls with Gothic gateway. Irregular wing with steep gables and dormers at back. Sold ca 1953. Now a novitiate of the Patrician Brothers.” [2]

The Record of Protected Structures describes the house’s porch as a loggia. It adds that the walls are of smooth rendering painted and the windows have late-19th century sashes. There is a single-storey wing on the right-hand side and an arch into the yard. The rear of the house has a two-storey service wing. The interior retains original decoration. The immediate grounds are contained within a ha-ha.

Jimmy O’Toole writes in his The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! Published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare.

Chapter: Lecky of Ballykealy

p. 147. “In 1953, the Lecky name was added to the growing list of departing gentry families from County Carlow. The Ballykealy seat had been in their possession since 1649, but not even three centuries of roots and tradition could hold back the tide of a rapidly changing financial climate that had already accounted for the departure of most of their neighbouring families. The 300 acre estate was bought by the Land Commission, and the house was purchased in the early 1960s for use as a noviciate for the Patrician Brothers, owners of the Wolseley family seat near Tullow since 1925.

“The sale of Ballykealy was the first tell-tale sign of looming financial problems for the last owner, Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Beauchamp Lecky, who moved to London with his family. Within four years, he had more debts than assets, and bankruptcy proceedings were instituted against him… On 26th Sept 1957, the War Office Colonel said his early morning good-byes to his wife and three children, got on a train for central London, and was never seen again by friends and family. Thirty six years on, the missing persons file on Colonel Lecky still remains open at Scotland Yard. ..

p. 149. The Lecky family were one of several Quaker families in Couty Carlow, the first of them having come to County Donegal from Stirling in Scotland during the reign of Eliz I. In 1873, John J. Lecky had 1,440 acres at Ballykealy; John F. Lecky had 44 acres at Lenham Lodge, and W.E.H. Lecky the historian had 721 acres at Aughanure, Bestfield and Kilcock. This property he inherited from his father John Lecky of Newgardens, and from his mother Maria Hartpole of Shrule Castle, Co Laois, he inherited an additional 1,200 acres.“

2. Borris House, Borris, County Carlow – wedding venue and Revenue section 482

Borris House is also open to the public on certain days as it is on the Revenue Section 482 list.

Open dates in 2026: Open: Apr 1, 2, 7-12, 14-26, 28-30, May 5-10, 19-24, June 12-14, 16-18, 23-25, 30, Aug 5, 12-23, 25, 26, Sept 1, 2, 8, 9, 22, 23, 29 12pm-4pm

Fee: adult €12, OAP/student €10, child under 12 free

See my write-up: https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/10/04/borris-house-county-carlow/

4. Lisnavagh, County Carlow, wedding venue and holiday cottages

Lisnavagh is a wedding venue, and there are buildings with accommodation, including the farm house, converted courtyard stables, the groom’s cottage, schoolhouse, farm and blacksmiths cottages and the bothy.

The house remains in the family that built it.

4. Sandbrook, Tullow, Co Carlow – wedding/retreat venue

The website tells us that Sandbrook is a handsome period country house, originally built in the early 1700s in Queen Anne style [the National Inventory says 1750], and sits in 25 acres of mature parkland on the Wicklow/Carlow border in the heart of the Irish Countryside with views toward Mount Leinster and the Wicklow Mountains. The National Inventory further describes it:

“five-bay two-storey over basement house with dormer attic, c. 1750, with pedimented central breakfront having granite lugged doorcase, granite dressings, two-bay lateral wings, Palladian style quadrant walls and pavilion blocks. Interior retains original features including timber panelled hall and timber staircase.“

It belonged to the Echlin family. There are records of an Anne Echlin who died in 1804 owning Sandbrook (see Jimmy O’Toole’s book, [6]). She seems to have leased it to Clement Wolseley when Mount Arran was burned during the 1798 Rebellion.

She left the property, consisting in total of 500 acres, to Robert Marshall of Dublin, and he sold to Brownes of Browne’s Hill for £488 in 1808. William Browne-Clayton moved to live in Sandbrook after his marriage to Caroline Watson-Barton in 1867 and remained there until he inherited Browne’s Hill on the death of his father, Robert Browne-Clayton, in 1888. Browne’s Hill in County Carlow still stands, a very impressive looking private house listed in the National Inventory.

O’Toole writes: “Sandbrook was another example of the many Irish country houses that attracted senior British army officers when they retired after the First and Second World Wars. General George Lewis bought the house in 1918 and after his wife’s death in 1938 the property was purchased by Brigadier Arthur George Rolleston who had retired from the army.

… In 1959 Sandbrook was purchased by John and Mary Allnatt… In the 1960s, Mrs. Allnatt purchased Rathmore Park for her son from her first marriage, Brendan Foody, but after he had decided not to return to live in Ireland, Rathmore was sold. He inherited Sandbrook following his mother’s death in September.”

The website tells us: “Sandbrook is the perfect venue for a family gathering or wedding celebration. With five interconnecting reception rooms downstairs, a covered terrace, huge lawn space and a separate loft space above converted stables there is a vast array of facilities should you wish to bring a group. Personal attention to detail and impeccable hospitality are evident throughout Sandbrook, with log fires burning in the hearths and fresh flowers in the hallways.“

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] p. 113, Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Lorum%20Rectory

[5] http://www.igp-web.com/Carlow/Lorum_Old_Rectory.htm

Source: http://www.hiddenireland.com/lorum/index.htm

[6] Jimmy O’Toole, The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! Published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare.

[7] http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlcar2/MOUNT_WOLSELEY.htm

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com