Open dates in 2026: Jan 10-12, 19-20, May 1-3, June 24-30, July 19-26, Aug 15-23, Sept 1-13, Nov 4-8, Dec 1-10, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €12, student/OAP/groups €8

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

We visited Clonskeagh Castle in December 2023. The name Clonskeagh comes from the Irish “Cluain Sceach” – the meadow of the white thorns. The house was built around 1789 as a country residence (he also had a house in the city) for Henry Jackson (d. 1817), who owned an iron foundry.

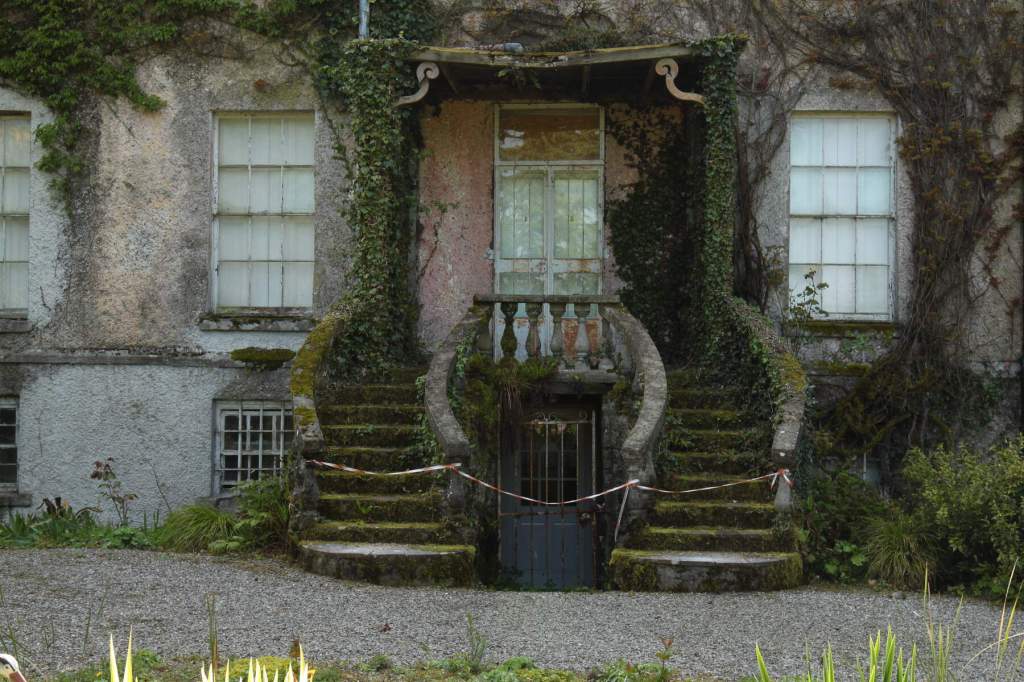

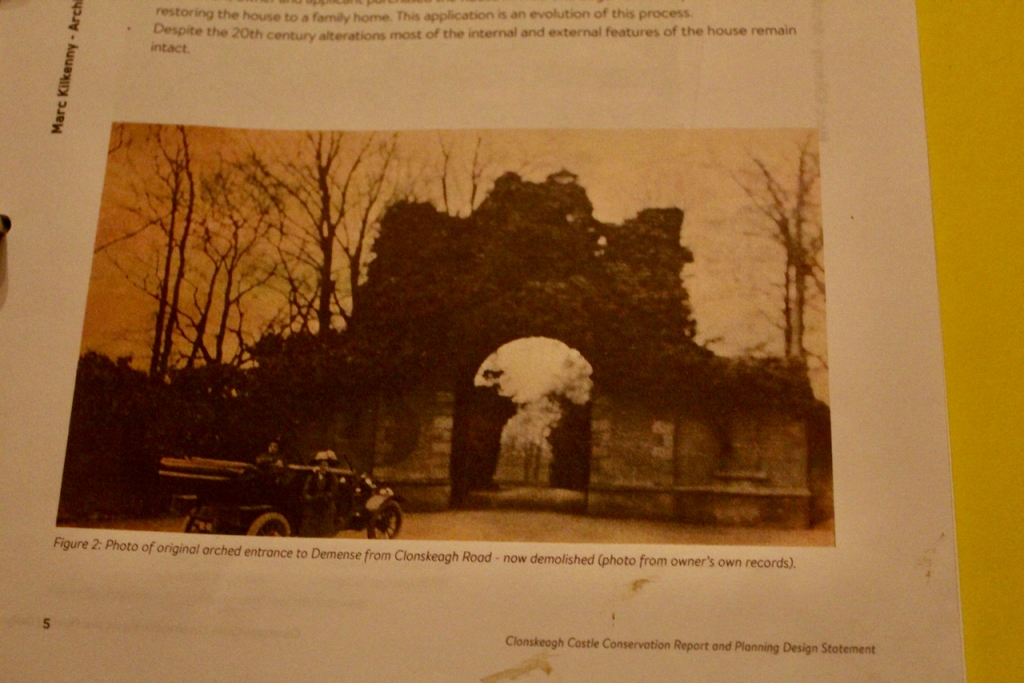

The house was built on an elevated site, and originally faced a toward the Dodder River. It was more compact than the “castle” as we see it today as it did not have the porch or the two towers that now stand at the present front of the house. The front door is less impressive than one would expect but this is because it was not the original front. The portico was added around 1886 when the house was inherited by Robert Wade Thompson.

The house was purchased by the parents of the current owner in 1992. The house had been converted into flats and the Armstrongs converted it back into use as a family home. They carried out much work on the building, with the benefit of research and guidance of architectural historian, Professor Alistair Rowan. The website tells us:

“The recent works [in 2019] have included restoration of the major portions of the parapet roof in accordance with best conservation practice; withdrawal of earth from the curtailage of the building, which had been piled up over at least a century giving rise to dampness in the walls; and restoration of rooms in what had been the servants’ quarters to create a small apartment.

“These works have been executed by Rory McArdle, heritage contractor, under the supervision of award-winning architect Marc Kilkenny, with frequent reference to the conservation experts at Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council. Fionan de Barra, architect, also provided valuable consultation at the early stages of the project.“

Frank Armstrong, the owner who showed us around, edits a magazine, https://cassandravoices.com/

In an article in the Irish Times published on October 6th 2022 written by Elizabeth Birdthistle, Marc Kilkenny said: “Working with my father-in-law at Clonskeagh Castle was an immense privilege. This house was like a member of the family and I felt honoured to be entrusted with the works… We reopened the original 18th century entrance to create a new sitting room which reintroduced south light into the entrance hall. We replaced the main roof and rerouted rainwater and transformed part of the basement into a light and spacious apartment with associated garden and steps up to a new terrace by the main kitchen. All works were carried out to the highest conservation standards.” [1]

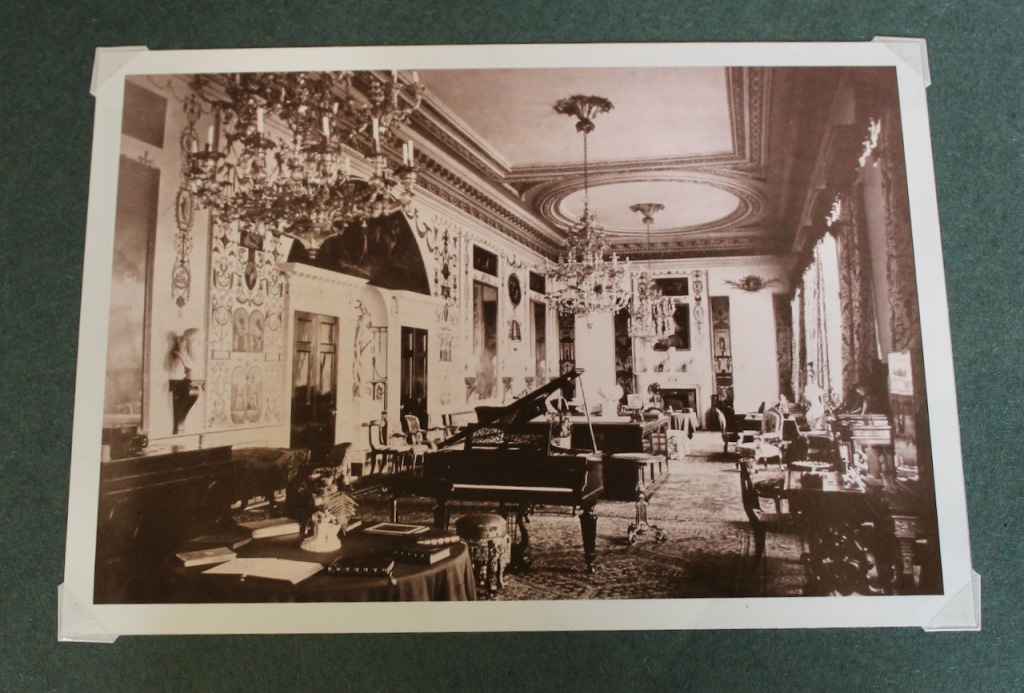

The house contains a beautiful curving staircase with iron balusters, and a spacious upstairs lobby with arches and large sash casement windows letting in the light.

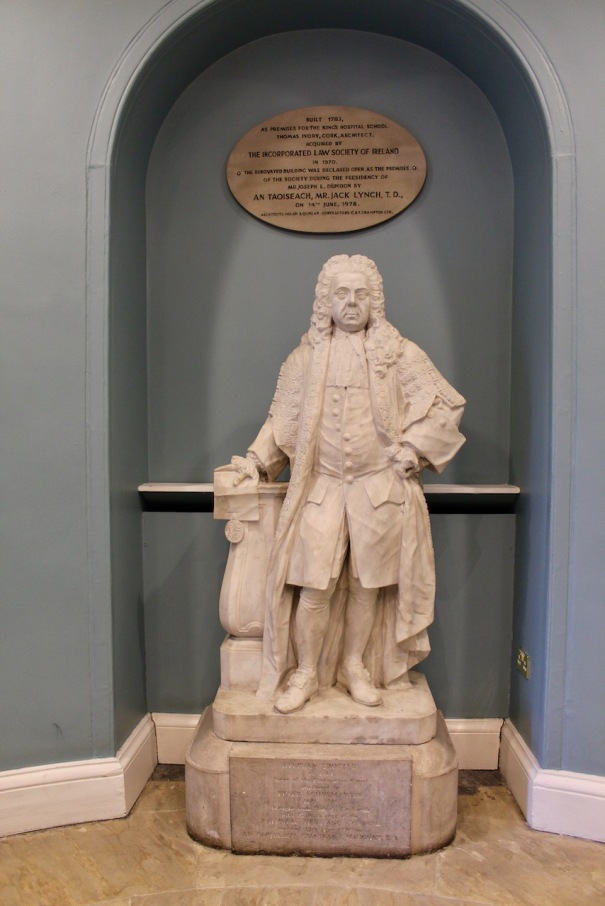

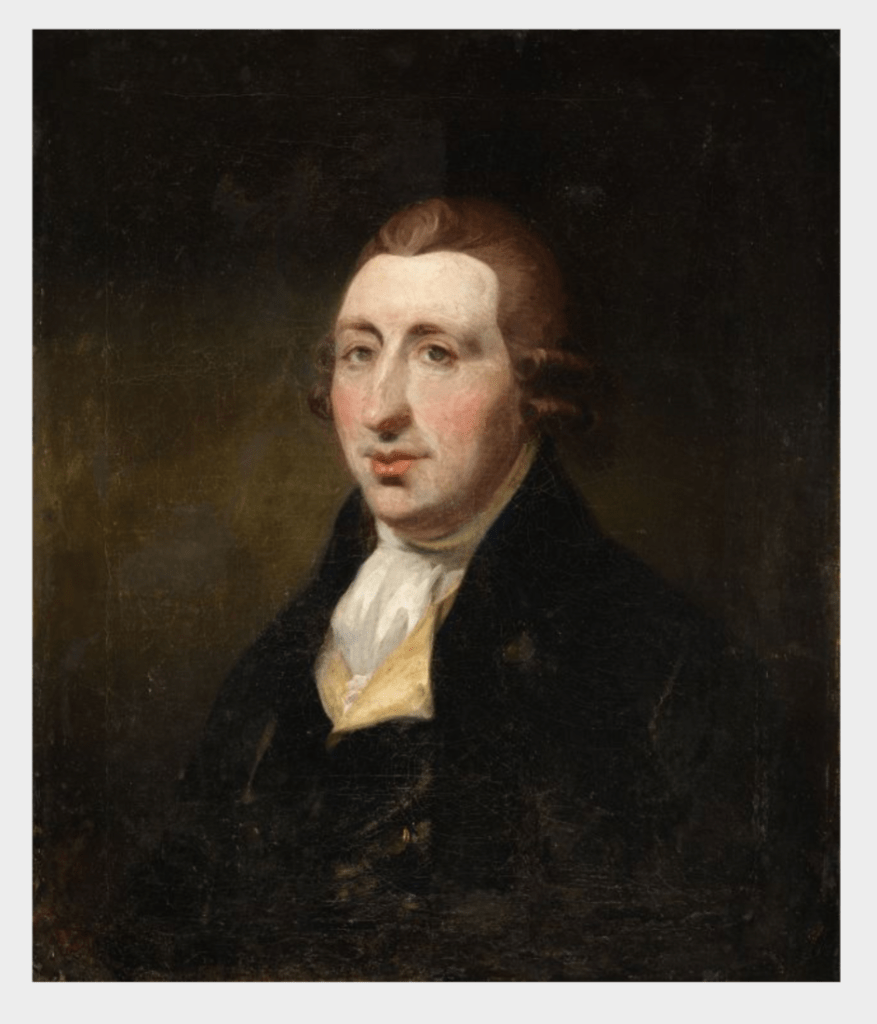

The original owner of the house, Henry Jackson, was the fourth son of Hugh Jackson (1710?–77) of Creeve, Co. Monaghan, and his wife Eleanor (née Gault), who belonged to a family engaged in the linen trade. [2] Hugh Jackson introduced the linen trade to Ballybay, Co. Monaghan, and generally improved the town.

Henry Jackson started in business as an ironmonger in 1766. The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that he is listed in the Dublin Directory from 1768 as an ironmonger in Pill Lane, and from 1787 as an iron founder or iron and brass founder in Old Church Street. In 1798 he also had mills for rolling and slitting iron on the quays and for grinding corn in Phoenix Street (both also steam powered) and iron mills at Clonskeagh.

Henry Jackson joined the United Irishmen. He was influenced by the writings of Thomas Paine, the author of The Rights of Man, and Jackson named the house “Fort Paine.” The Society of United Irishmen was formed at a gathering in a Belfast tavern in October 1791. They were influenced by the ideals of the French Revolution, and they wanted to secure “an equal representation of all the people” in a national government. The founders were mostly Presbyterian but they vowed to make common cause with Irish Catholics. Presbyterians as well as Catholics had suffered under the Penal Laws in Ireland, as Presbyterians were “dissenters” from the established Protestant religion. Most of the original United Irishmen were members of the Irish Volunteers, which were local militias set up to keep order and safety when British soldiers were withdrawn from Ireland to fight in the American Revolutionary War (or as those in America call it, the War of Independence).

In Dublin on 4 November 1779, the Volunteers took advantage of the annual commemoration of King William III’s birthday, marching to his statue in College Green and demonstrating for the cause of free trade between Ireland and Great Britain. Previously, under the Navigation Acts, Irish goods had been subject to tariffs upon entering Britain, whereas British goods could pass freely into Ireland.

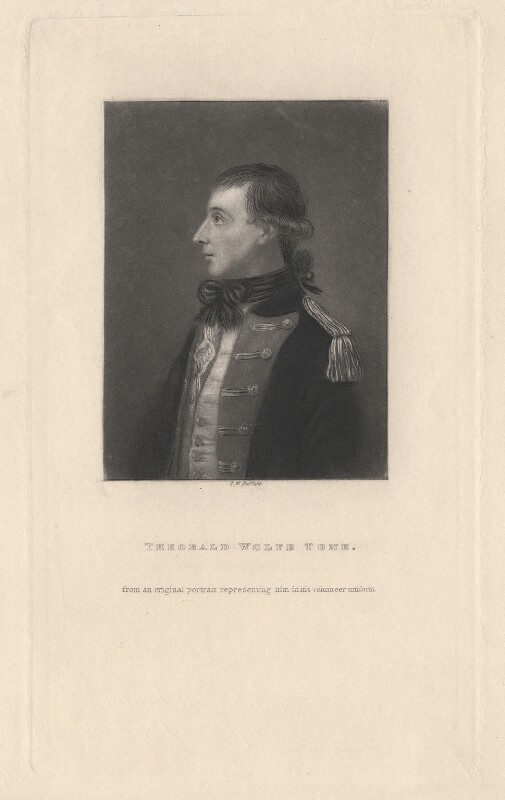

Theobald Wolfe Tone was one of the founders of the United Irishmen. Thomas Russell had invited Tone, as the author of An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland, to the Belfast gathering in October 1791. By 1798, Tone instigated Rebellion for independence and the formation of a republic in Ireland, and he sought the help of the French. Although Protestant, Tone was secretary to Dublin’s Catholic Committee, a group which had been formed to seek repeal of the Penal Laws. The Catholic Committee was formed in 1757 by Charles O’Conor of Belanagare in County Sligo (see my entry about Clonalis).

In 1786 Henry Jackson, who was from a Presbyterian family, joined his son-in-law Oliver Bond, along with James Napper Tandy and Archibald Hamilton Rowan, to form a Dublin battalion of the Volunteers. He was also a member of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen. He sat on several of its committees, acting as its secretary and later as its treasurer, and was present at what proved to be the final meeting of the society when it was raided by the police (23 May 1794).

Henry Jackson of Clonskeagh Castle used his foundry to make pikes for the 1798 Rebellion. The website tells us:

“Jackson was involved in preparations for the 1798 Rebellion, and his foundries were engaged to manufacture pikes for combat, and also iron balls of the correct bore to fit French cannons, in anticipation of an expected invasion. His son-in-law Oliver Bond was also heavily implicated in these plans.

“In the event, Jackson was arrested before the ill-fated Rebellion, and imprisoned in England. After some time he was released on condition that he went into exile in America. He died in the city of Baltimore, Maryland in 1817.“

Frank told us that the lyrics of the song “By the Rising of the Moon” may refer to the foundry in Clonskeagh. The lyrics of the song include:

“At the rising of the moon, at the rising of the moon

For the pikes must be together at the rising of the moon

And come tell me Sean O’Farrell, where the gathering is to be

At the old spot by the river quite well known to you and me.“

There are tunnels under the house which were perhaps used by Jackson to store his pikes and cannonballs.

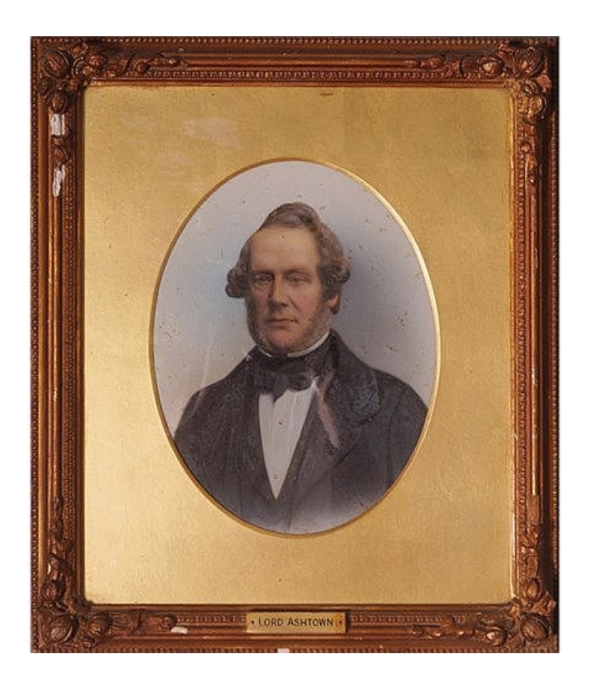

The Clonskeagh Castle website continues: “In 1811 the Castle was purchased by George Thompson, a landed proprietor, who had a post in the Irish Treasury, and it remained in the ownership of that family until the early twentieth century. It is interesting to note that whereas Henry Jackson was fired by the objective of Irish independence, the last Thompson family member to occupy the house was vehemently insistent on the preservation of the Union.“

Thompson made alterations to the house and made what was formerly the back of the house into the front. The Armstrongs note that the hallway was thus left quite dark, and they did renovation work to allow light to penetrate from the south.

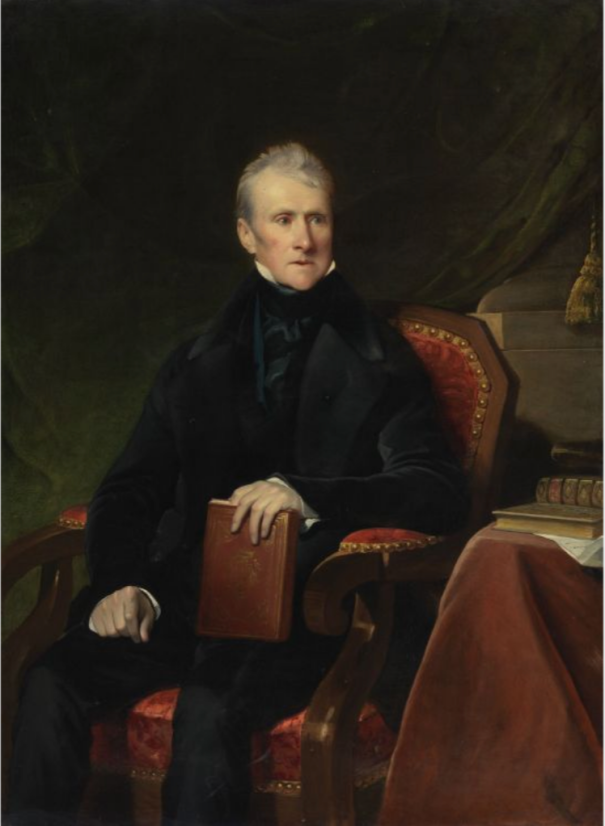

The house passed from George Thompson (1769-1860) to his son Thomas Higinbotham Thompson, to his son Robert Wade Thompson (1845-1919). [3] Robert Wade Thompson was a barrister, who married Edith Isabella Jameson, daughter of Reverend William Jameson (1811-1886) and Elizabeth Guinness (1813-1897). Reverend William Jameson was son of John Jameson of Jameson’s Whiskey Company. Elizabeth was the daughter of Arthur Hart Guinness (1768-1855) who was the son of Arthur Guinness (1725-1803), founder of Guinness Brewery.

The house then passed to Robert Wade Thompson’s son Thomas William Thompson in 1919.

The website tells us: “During the War of Independence (1919-1921) the Castle was occupied by the British military, and was used for some time to incarcerate Irish Republicans.“

The castle was purchased in 1934 by G&T Crampton, a property development company who later developed the redbrick houses that now stand on the nearby Whitethorn, Whitebeam and Maple Roads.

Frank showed us a couple of books about the area. The house was for sale when we visited. The new owners will be very lucky to own piece of Irish history.

[2] https://www.dib.ie/biography/jackson-henry-a4235

[3] https://www.famousjamesons.com

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com