Westmeath:

1. Fore Abbey in County Westmeath

Wexford:

1. Ballyhack Castle, County Wexford – closed at present

2. Ferns Castle, County Wexford – closed at present

3. John F. Kennedy Arboretum, County Wexford

4. Tintern Abbey, County Wexford

Wicklow:

1. Dwyer McAllister Cottage, County Wicklow – closed at present

2. Glendalough, County Wicklow

3. National Botanic Gardens Kilmacurragh, County Wicklow

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Westmeath:

1. Fore Abbey in County Westmeath:

“Fore” comes from the Irish “fobhar” meaning well or spring.

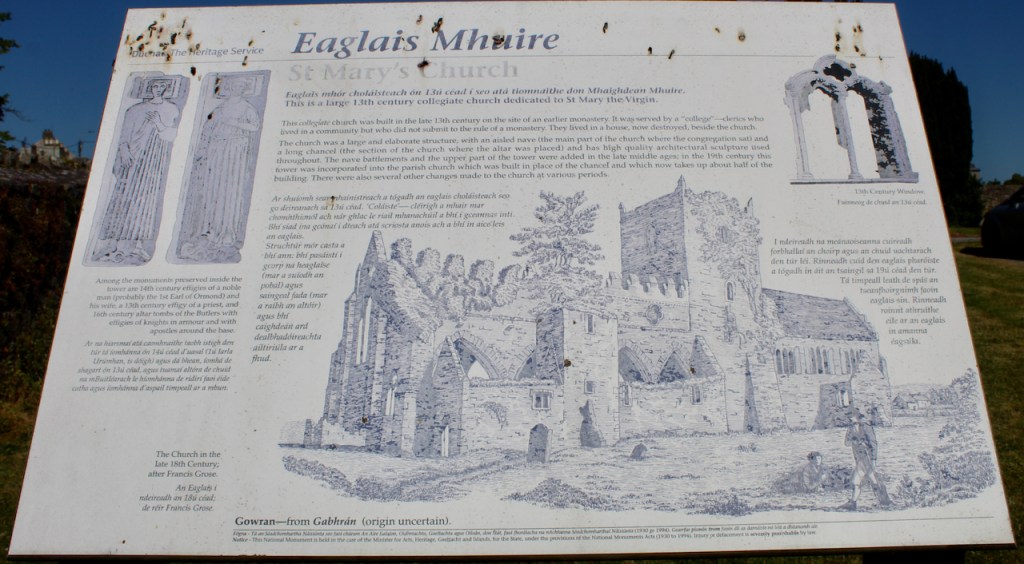

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/fore-abbey/:

“In a tranquil valley in the village of Fore, about a 30-minute drive from Mullingar in County Westmeath, you can visit the spot where St Feichin founded a Christian monastery in the seventh century AD.

“It is believed that, before Feichin’s death, 300 monks lived in the community. Among the remains on the site is a church built around AD 900. There are also the 18 Fore crosses, which are spread out over 10 kilometres on roadways and in fields.

“Seven particular features of the site – the so-called ‘Seven Wonders of Fore’ – have acquired legendary status. They include: the monastery built on a bog; the mill without a race (the saint is said to have thrust his crozier into the ground and caused water to flow); and the lintel stone raised by St Feichin’s prayers.

“St Feichin’s Way, a looped walk around the site, provides an excellent base from which to explore these fabled places.“

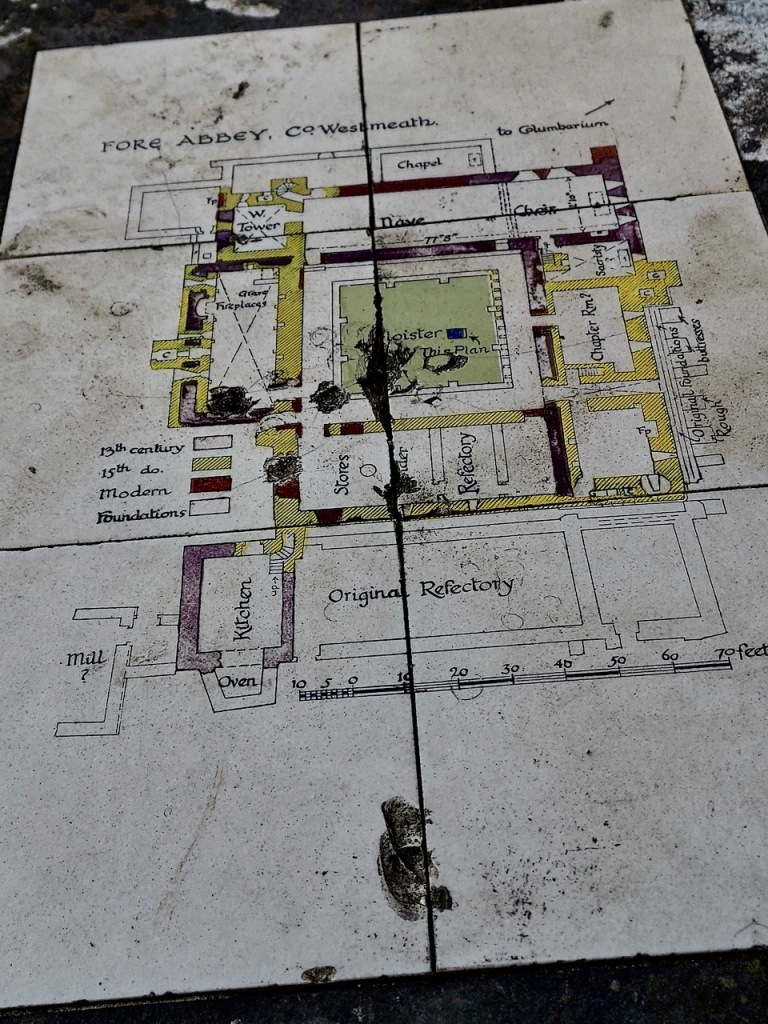

The Benedictine Priory was founded around 1180 by Hugh de Lacy, the first Viceroy of Ireland. Before this there was a monastery in Fore, founded by Feichin in the seventh century. The Benedictines had a link with France and its first monks came from France. The Priory sufffered plundering attacks so needed defensive towers and fortification. It was built around a Cloister or courtyard.

The “columbarium” mentioned in the diagram is a house for keeping pigeons – we saw one previously at Moone Abbey tower, and there is one at Fore.

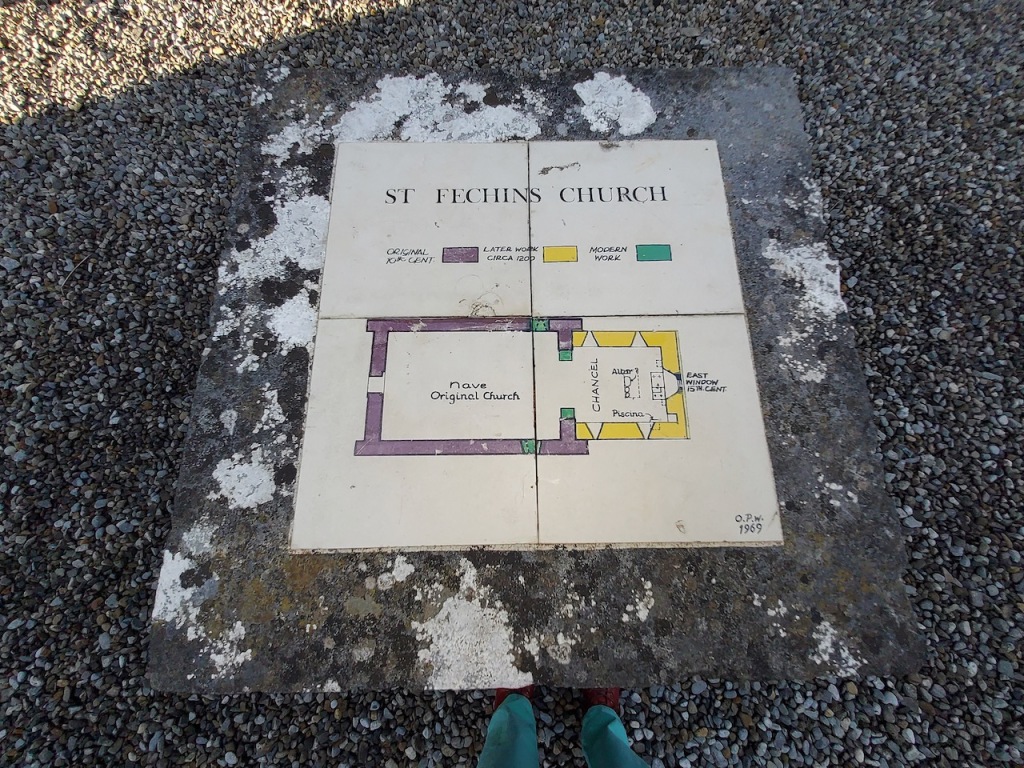

The monastery founded at Fore in the seventh century by St Feichin, a Sligo-born holy man who travelled widely in Ireland, was large and prosperous but was superceded by Fore Abbey, the nearby Benedictive abbey founded by the Norman deLacys. The remaining building of St Feichins is the church, which was built in the tenth century. A new chancel was added around 1200, and the arch leading to this was re-erected in 1934. The east window was inserted in the 15th century.

The Anchorite’s Cell is a small tower with attached chapel. The tower had two storeys and on the top floor lived a number of Anchorites, or hermits. The chapel has a vault below, the crypt of the Nugent family of nearby Castle Delvin and Clonyn Castle, Earls of Westmeath. Delvin, or Castletown-Delvin, was granted by Hugh de Lacy to his son-in-law Gilbert de Nugent. The 1st Earl of Westmeath was Richard Nugent (1583-1642). His father was Christopher Nugent, 5th Baron Delvin.

County Wexford:

1. Ballyhack Castle, Arthurstown, County Wexford

General enquiries: 051 398 468, breda.lynch@opw.ie

from the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/ballyhack-castle/:

“Ballyhack Castle commands an imperious position on a steep-sided valley overlooking Waterford Estuary. It is thought that the Knights Hospitallers of St John, one of the two mighty military orders founded at the time of the Crusades, built this sturdy tower house around 1450.

“The tower is five stories tall and the walls survive complete to the wall walk. Built into the north-east wall of the second floor is a small chapel complete with a piscina, aumbry and altar. The entrance to the castle is protected externally by a machicolation and internally by a murder hole – that is, an opening through which defenders could throw rocks or pour boiling water, hot sand or boiling oil, on anyone foolish enough to attack.

“Currently on display at Ballyhack Castle are assorted items of replica armour relating to the Crusades and the Normans – guaranteed to ignite the imagination!“

2. Ferns Castle, County Wexford:

General information: 053 9366411, fernscastle@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/ferns-castle/:

“Before the coming of the Normans, Ferns was the political base of Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster. William, Earl Marshall built the castle around 1200. Since then it has had many owners, of diverse political and military colours.

“Originally, the castle formed a square, with large corner towers. Only half of the castle now stands, although what remains is most impressive. The most complete tower contains a beautiful circular chapel, several original fireplaces and a vaulted basement. There is a magnificent view from the top.

“There is an extraordinary artefact to be seen in the visitor centre. The Ferns Tapestry showcases the pre-Norman history of the town via the thousand-year-old art of crewel wool embroidery. Stitched by members of the local community, the 15-metre-long tapestry comprises 25 panels of remarkable accomplishment and beauty.“

3. John F. Kennedy Arboretum, County Wexford:

General Information: 046 9423490, jfkarboretum@opw.ie

When John F. Kennedy died, a number of Irish-American societies expressed the wish to establish a tribute to him in Ireland. The Irish government suggested a national arboretum, and secured 192 acres surrounding Ballysop House, just six kilometres from the Kennedy ancestral home at Dunganstown, County Wexford. The arborterum is planted in two interwoven botanical circuits: one of broadleaves and the other of conifers. The Arboretum was formally opened on 29th May 1968.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/the-john-f-kennedy-arboretum/:

“Dedicated to the memory of John F. Kennedy, whose great-grandfather, Patrick, was born in the nearby village of Dunganstown, this arboretum near New Ross, County Wexford, contains a plant collection of presidential proportions.

“It covers a massive 252 hectares on the summit and southern slopes of Slieve Coillte and contains 4,500 types of trees and shrubs from all temperate regions of the world. There are 200 forest plots grouped by continent. Of special note is an ericaceous garden with 500 different rhododendrons and many varieties of azalea and heather, dwarf conifers and climbing plants.

“The lake is perhaps the most picturesque part of the arboretum and is a haven for waterfowl. There are amazing panoramic views from the summit of the hill, 271 metres above sea level. A visitor centre houses engaging exhibitions on JFK and on the Arboretum itself.“

Along the northern perimeter of the site are some 200 forest plots. Each covers an area of one acre and comprises a single species of forestry tree. These provide information on the performance of different types of plantation species in the Irish climate.

Through the garden are a number of trails, and a miniature train runs during the summer, and there is a cafe.

4. Tintern Abbey, County Wexford:

See my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/04/07/tintern-abbey-county-wexford-an-opw-property/

General information: 051 562650, tinternabbey@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/tintern-abbey/:

“This Cistercian monastery was founded c. 1200 by William, Earl Marshal on lands held through his marriage to the Irish heiress, Isabella de Clare [daughter of Strongbow]. This abbey, founded as a daughter-house of Tintern Major in Wales is often referred to as Tintern de Voto.“

“The nave, chancel, tower, chapel and cloister still stand. In the 16th century the old abbey was granted to the Colclough family [Anthony Colclough (d. 1584) was a soldier and the land was granted to him after the dissolution of the monasteries] and soon after the church was partly converted into living quarters and further adapted over the centuries. The Colcloughs occupied the abbey from the sixteenth century until the mid-twentieth.”

Wicklow:

1. Dwyer McAllister Cottage, County Wicklow:

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/dwyer-mcallister-cottage/:

“This thatched and whitewashed cottage nestles in the shade of Keadeen Mountain off the Donard to Rathdangan road in County Wicklow.

“Today, it seems like an unlikely site of conflict. However, in the winter of 1799 it was a different story. It was from this cottage that the famed rebel Michael Dwyer fought the encircling British. One of Dwyer’s compatriots, Samuel McAllister, drew fire upon himself and was killed. This allowed Dwyer to make good his escape over the snow-covered mountains.

“The cottage was later destroyed by fire and lay in ruins for almost 150 years. It was restored to its original form in the twentieth century. Now, it contains various items of the period – both those that characterised everyday life, such a roasting spit and a churn, and those that only appeared in the throes of combat, such as deadly pikes.“

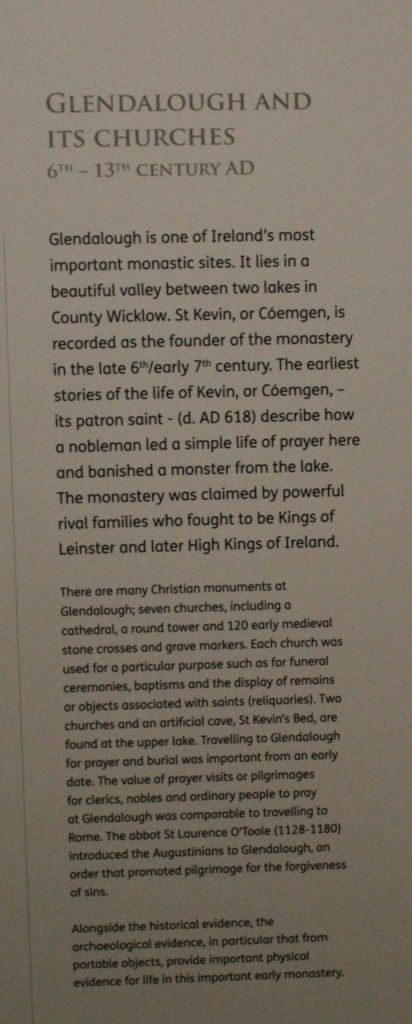

2. Glendalough, County Wicklow:

General information: 0404 45352, george.mcclafferty@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/glendalough-visitor-centre/:

“In a stunning glaciated valley in County Wicklow, in the sixth century, one of Ireland’s most revered saints founded a monastery. The foundation of St Kevin at Glendalough became one of the most famous religious centres in Europe.

“The remains of this ‘Monastic City’, which are dotted across the glen, include a superb round tower, numerous medieval stone churches and some decorated crosses. Of particular note is St Kevin’s Bed, a small man-made cave in the cliff face above the Upper Lake. It is said that St Kevin lived and prayed there, but it may actually be a prehistoric burial place that far predates him.“

3. National Botanic Gardens Kilmacurragh, County Wicklow:

General Information: 0404 48844, botanicgardens@opw.ie

Kilmacurragh House was home to seven generations of the Acton family. It was built in 1697 by Thomas Acton, whose father came to Ireland as part of Oliver Cromwell’s army, for which he was granted the lands surrounding the ruined abbey of St. Mochorog. The five bay Queen Anne house is thought to be the work of Sir William Robinson, who is better known today for his work at Marsh’s Library in Dublin, the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, Dublin Castle and Charles Fort, Kinsale, County Kerry. [2]

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/national-botanic-gardens-kilmacurragh/:

“There was a monastery at Kilmacurragh, in this tranquil corner of County Wicklow, in the seventh century, and a religious foundation remained right up until the dissolution of the monasteries. After Cromwell invaded the land passed to the Acton family.“

“By the time the estate came to Thomas Acton in 1854, an unprecedented period of botanical and geographical exploration was afoot. In collaboration with the curators of the National Botanic Gardens, Acton built a new and pioneering garden.

“In 1996, a 21-hectare portion of the old demesne officially became part of the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland. The following ten years were spent giving the estate’s rare and beautiful plants a new lease of life.

“Kilmacurragh is now part of the National Botanic Gardens, providing a complementary collection of plants to its parent garden at Glasnevin. Arrive in spring to witness the transformation of the walks, as fallen rhododendron blossoms form a stunning magenta carpet.“

and

“The Gardens lies within an estate developed extensively during the nineteeth century by Thomas Acton in conjunction with David Moore and his son Sir Frederick Moore, Curators of the National Botanic Gardens at that time. It was a period of great botanical and geographical explorations with numerous plant species from around the world being introduced to Ireland for the first time. The different soil and climatic conditions at Kilmacurragh resulted in many of these specimens succeeding there while struggling or failing at Glasnevin. Kilmacurragh is particularly famous for its conifer and rhododendron collections.” [4]

Thomas Acton’s son William (1711-1779) married Jane Parsons of Birr Castle. Their son Thomas Acton (1738-1817) inherited, then his son Lt Col William (1789-1854) and then his son Thomas (1826-1908). Along with his sister Janet, he had a passion for collecting plants. They travelled to the Americas and Asia in search of plants, and established one of the finest arboreta in Ireland, and formed a friendship with David Moore, curator of the National Botanic Gardens in Dublin. Thomas died unmarried in 1908 and Kilmacurragh was inhierted by his nephew, Captain Charles Annesley Acton, who had been born in Peshawar. However, he was killed fighting in World War I as was his brother Reginald. Thus in eight years, three consecutive owners of Kilmacurragh had died, inflicting death duties amounting to 120% of the value of the property. The Actons were forced to sell the estate. The house fell into ruin and the arboretum became overgrown. The state acquired Kilmacurragh in 1996 and have restored the arboretum, making it part of the National Botanic Gardens.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/media/81101

[2] p. 160. Living Legacies: Ireland’s National Historic Properties in the Care of the OPW. Government Publications, Dublin 2, 2018.

[3] Burke, Bernard, A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, 1886 vol 1.