www.bantryhouse.com

Open dates in 2025: Apr 12-30, May 1-16, 18-30, June 1-30, July 1-11, 13-24, 26-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1-26, 28-30, 10am-5pm

Fee: adult €14, OAP/student €11.50, child €5, any other concessions groups 8-20 people €10 and groups of 21or more people €9

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

What we see today at Bantry House started as a more humble abode: a three storey five bay house built for Samuel Hutchinson in around 1690. It was called Blackrock. A wing was added in 1820, and a large further addition in 1845.

In the 1760s it was purchased by Captain Richard White (1700-1776). He was from a Limerick mercantile family and he had settled previously on Whiddy Island, the largest island in Bantry Bay. The Bantry website tells us that he had amassed a fortune from pilchard-fishing, iron-smelting and probably from smuggling, and that through a series of purchases, he acquired most of the land around Bantry including large parts of the Beare Peninsula, from Arthur Annesley, 5th Earl of Anglesey. The house is still occupied by his descendants, the Shelswell-White family.

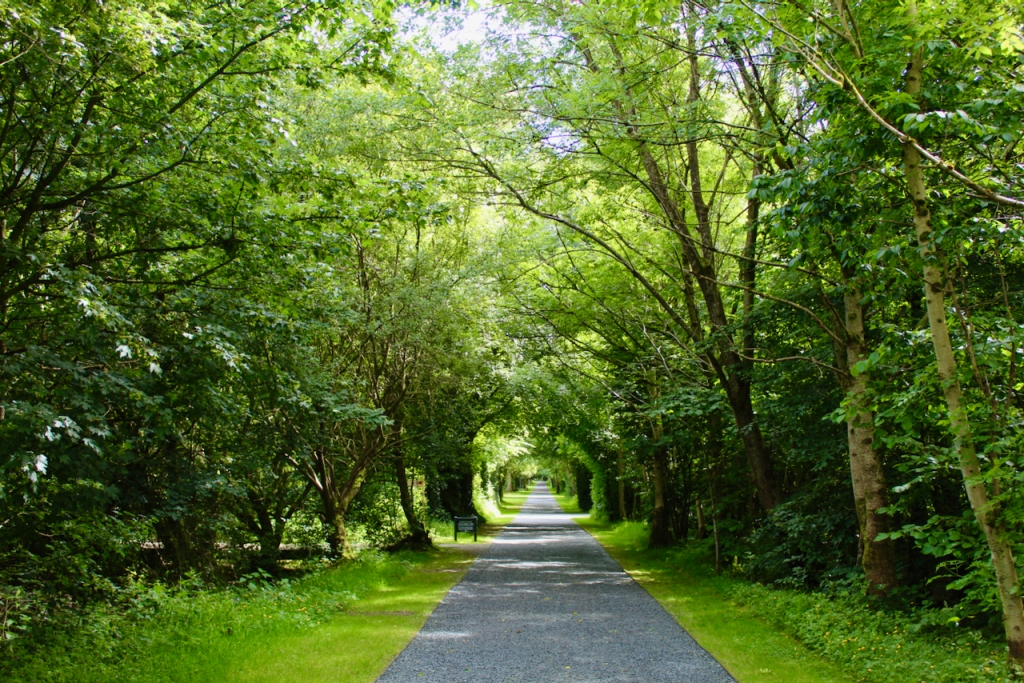

Driving from Castletownshend, we entered the back way and not through the town. From the car park we walked up a path which gave us glimpses of the outbuildings, the west stables, and we walked all around the house to reach the visitors’ entrance. We were lucky that the earlier rain stopped and the sun came out to show off Bantry House at its best. I was excited to see this house, which is one of the most impressive of the Section 482 houses.

We missed the beginning of the tour, so raced up the stairs to join the once-a-day tour in June 2022. Unfortunately I had not been able to find anything about tour times on the website. We will definitely have to go back for the full tour! The house is incredible, and is full of treasures like a museum. I’d also love to stay there – one can book accommodation in one wing.

Captain Richard White married Martha Davies, daughter of Rowland Davies, Dean of Cork and Ross. During his time, Bantry House was called Seafield. They had a son named Simon (1739-1776), who married Frances Hedges-Eyre from Macroom Castle in County Cork. Their daughter Margaret married Richard Longfield, 1st Viscount Longueville.

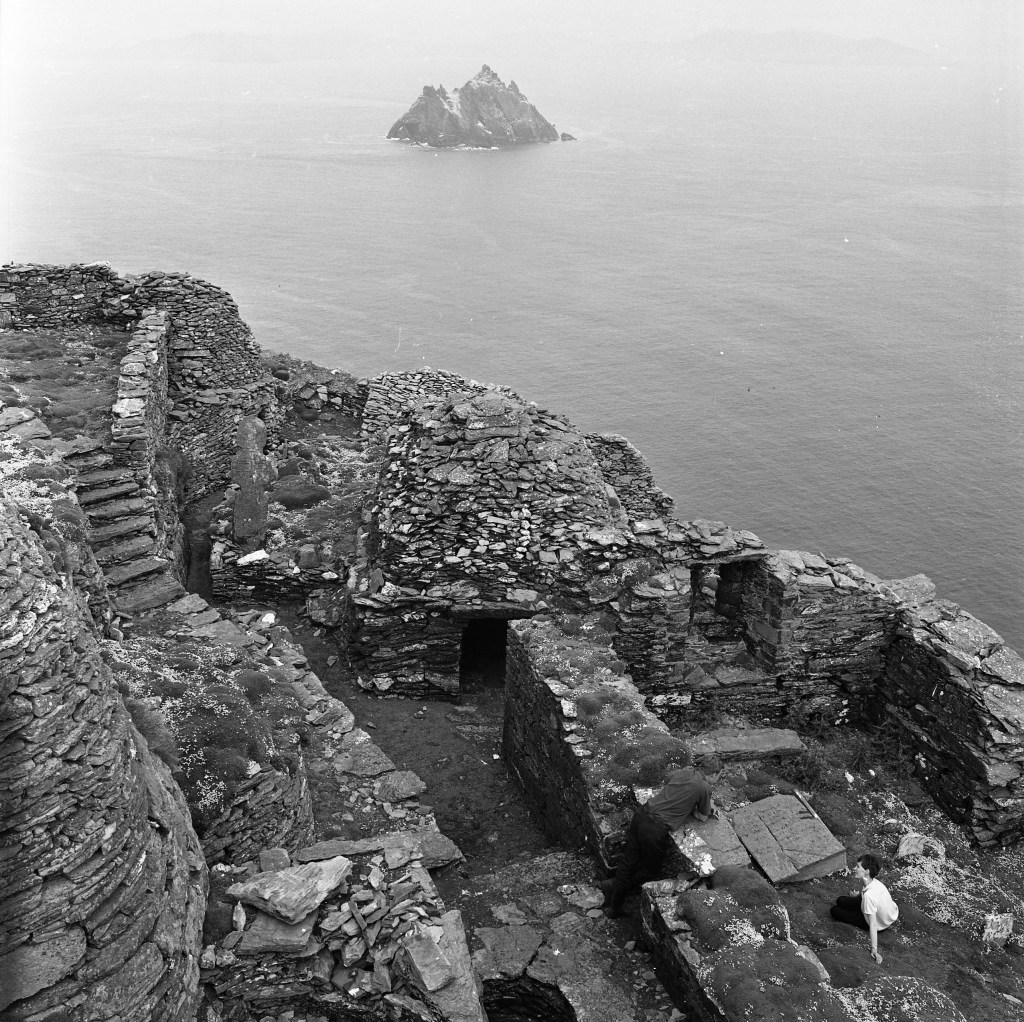

The house overlooks Bantry Bay which is formative in its history because thanks to its views, Richard’s grandson was elevated to an Earldom.

Frances Jane and Simon had a son, Richard (1767-1851), who saw French ships sail into Bantry Bay in 1796. The British and French were at war from February 1793. It was in gratitude for Richard’s courage and foresight in raising a local militia against the French that Richard was given a title.

There are four guns overlooking the bay. The two smaller ones are from 1780, and the larger one is dated 1796. One is French and dated 1795 and may have been captured from an invading French ship.

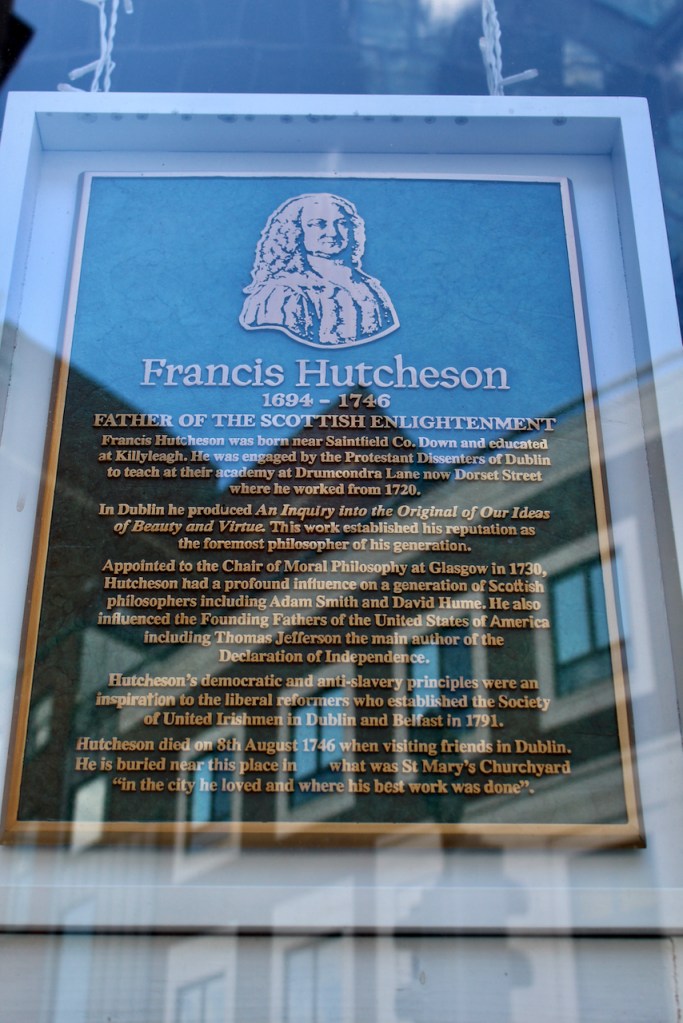

United Irishman Theobald Wolfe Tone was on one of the French ships, which were under command of French Louis Lazare Hoche.

Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763–98) (named after his godfather, Theobald Wolfe) had sought French support for an uprising against British rule in Ireland. The United Irishmen sought equal representation of all people in Parliament. Tone wanted more than the Catholic Emancipation which Henry Grattan advocated, and for him, the Catholic Relief Act of 1793 did not go far enough, as it did not give Catholics the right to sit in the Irish House of Commons. Tone was inspired by the French and American Revolutions. The British had specifically passed the Catholic Relief Act in the hope of preventing Catholics from joining with the French.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us that

“With the outbreak of war with France, Dublin Castle instituted a crackdown on Irish reformers who had professed admiration for the French, and by the end of the year the United Irishmen and the reform movement were in disarray. In quick succession, the Volunteers were proscribed, the holding of elected conventions was banned, and a number of United Irishmen… were hauled before the courts on charges of seditious libel.“

Tone went to the U.S. and thought he might have to settle there but with others’ encouragement he continued in his work for liberating Ireland. He went to France for support. As a result 43 ships were sent to France.

“In July 1796 Tone was appointed chef de brigade (brigadier-general) in Hoche’s army ... Finally, on 16 December 1796, a French fleet sailed from Brest crammed with 14,450 soldiers. On board one of the sails of the line, the Indomptable, was ‘Citoyen Wolfe Tone, chef de brigade in the service of the republic.’” [1]

Richard White had trained a militia in order to defend the area, and stored munitions in his house. When he saw the ships in the bay he raised defenses. However, it was stormy weather and not his militia that prevented the invasion. Tone wrote of the expedition in his diary, saying that “We were close enough to toss a biscuit ashore”.

The French retreated home to France, but ten French ships were lost in the storm and one, the Surveillante, sank and remained on the bottom of Bantry bay for almost 200 years.

For his efforts in preparing the local defences against the French, Richard White was created Baron Bantry in 1797 in recognition of his “spirited conduct and important service.” In 1799 he married Margaret Anne Hare (1779-1835), daughter of William the 1st Earl of Listowel in County Kerry, who brought with her a substantial dowry. In 1801 he was made a viscount, and in 1815 he became Viscount Berehaven and Earl of Bantry. He became a very successful lawyer and made an immense fortune.

Richard was not Simon White’s only son. Simon’s son Simon became a Colonel and married Sarah Newenham of Maryborough, County Cork. They lived in Glengariff Castle. Young Simon’s sister Helen married a brother of Sarah Newenham, Richard, who inherited Maryborough. Another daughter, Martha, married Michael Goold-Adams of Jamesbrook, County Cork and another daughter, Frances, married General E. Dunne of Brittas, County Laois. Another son, Hamilton, married Lucinda Heaphy.

A wing was added to the house in 1820 in the time of the 1st Earl of Bantry. This wing is the same height as the original block, but of only two storeys, and faces out to the sea. It has a curved bow at the front and back and a six bay elevation at the side. This made space for two large drawing rooms, and more bedrooms upstairs.

The house was greatly enlarged and remodelled in 1845 by the son of the 1st Earl, Richard (1800-1867). The 1st Earl had moved out to live in a hunting lodge in Glengariff. This son Richard was styled as Viscount Berehaven between 1816 and 1851 until his father died, when he then succeeded to become 2nd Earl of Bantry. He married Mary O’Brien, daughter of William, 2nd Marquess of Thomond, in 1836.

The 2nd Earl of Bantry and his wife travelled extensively and purchased many of the treasures in the house. The website tells us he was a passionate art collector who travelled regularly across Europe, visiting Russia, Poland, France and Italy. He brought back shiploads of exotic goods between 1820 and 1840.

To accommodate his new furnishings he built a fourteen bay block on the side of the house opposite to the 1820 addition, consisting of a six-bay centre of two storeys over basement flanked by four-storey bow end wings.

The website tells us:

.”..No doubt inspired by the grand baroque palaces of Germany, he gave the house a sense of architectural unity by lining the walls with giant red brick pilasters with Coade-stone Corinthian capitals, the intervening spaces consisting of grey stucco and the parapet adorned with an attractive stone balustrade.“

He also lay out the Italianate gardens, including the magnificent terraces on the hillside behind the house, most of which was undertaken after he had succeeded his father as the second Earl of Bantry in 1851.

After his death in 1867 the property was inherited by his brother William, the third Earl (1801-1884), his grandson William the fourth and last Earl (1854-91), and then passed through the female line to the present owner, Mr. Shelswell-White.

Mark Bence-Jones tells us: “The house is entered through a glazed Corinthian colonnade, built onto the original eighteenth century front in the nineteenth century; there is a similar colonnade on the original garden front.” [2]

Unfortunately we were not allowed to take photographs inside. You can see photographs of the incredible interior on the Bantry house website, and on the Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne’s blog. [3]

The rooms are magnificent, with their rich furnishings, ceilings and columns. Old black and white photographs show that even the ceilings were at one time covered in tapestries. The Spanish leather wallpaper in the stair hall is particularly impressive.

Mark Bence-Jones continues: “The hall is large but low-ceilinged and of irregular shape, having been formed by throwing together two rooms and the staircase hall of the mid-eighteenth century block; it has early nineteenth century plasterwork and a floor of black and white pavement, incorporating some ancient Roman tiles from Pompeii. From one corner rises the original staircase of eighteenth century joinery.”

The website tells us: “Today the house remains much as the second earl left it, with an important part of his great collection still intact. Nowhere is this more son than the hall where visitors will find an eclectic collection garnered from a grand tour, which includes an Arab chest, a Japanese inlaid chest, a Russian travelling shrine with fifteenth and sixteenth century icons and a Fresian clock. There is also a fine wooden seventeenth century Flemish overmantel and rows of family portraits on the walls. The hall was created by combining two rooms with the staircase hall of the original house and consequently has a rather muddled shape, though crisp black and white Dutch floor tiles lend the room a sense of unity.. Incorporated into this floor are four mosaic panels collected by Viscount Berehaven from Pompeii in 1828 and bearing the inscriptions “Cave Canem” and “Salve.” Other unusual items on show include a mosque lamp from Damascus in the porch and a sixteenth century Spanish marriage chest which can be seen in the lobby.“

Bence-Jones continues: “The two large bow-ended drawing rooms which occupy the ground floor of the late eighteenth century wing are hung with Gobelins tapestries; one of them with a particularly beautiful rose-coloured set said to have been made for Marie Antoinette.“

The Royal Aubusson tapestries in the Rose drawing room, comprising four panels, are reputed to have been a gift from the Dauphin to his young wife-to-be Marie Antoinette. In the adjoining Gobelin drawing room, one panel of tapestries is said to have belonged to Louis Philippe, Duc D’Orleans, a cousin of Louis XV.

The website tells us: “The most spectacular room is the dining-room, dominated by copies of Allan Ramsay’s full-length portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte, whose elaborate gilt frames are set off by royal blue walls. The ceiling was once decorated with Guardi panels, but these have long since been removed and sold to passing dealers at a fraction of their worth. The differing heights of the room are due to the fact that they are partly incorporated in the original house and in the 1845 extension, their incongruity disguised by a screen of marble columns with gilded Corinthian capitals. Much of the furniture has been here since the second Earl, including the George III dining table, Chippendale chairs, mahogany teapoy, sideboards made for the room, and the enormous painting The Fruit Market by Snyders revealing figures reputedly drawn by Rubens – a wedding present to the first Countess.“

The Chippendale chairs and the George III dining table were made for the room.

The description on the website continues: “The first flight of the staircase from the hall belongs to the original early eighteenth century house, as does the half-landing with its lugged architraves. This leads into the great library, built around 1845 and the last major addition to the house. The library is over sixty feet long, has screens of marble Corinthian columns, a compartmented ceiling and Dublin-made mantelpieces at each end with overhanging mirrors. The furnishing retains a fine rosewood grand piano by Bluthner of Leipzig, still occasionally used for concerts. The windows of this room once looked into an immense glass conservatory, but this has now been removed and visitors can look out upon restored gardens and the steep sloping terraces behind. “

The third Earl, William Henry (1801-1884), succeeded his brother, who died in 1868. On 7 September 1840 William Henry’s surname was legally changed to William Henry Hedges-White by Royal Licence, adding Hedges, a name passed down by his paternal grandmother.

His grandmother was Frances Jane Eyre and her father was Richard Hedges Eyre. Richard Hedges of Macroom Castle and Mount Hedges, County Cork, married Mary Eyre. Richard Hedges Eyre was their son. He married Helena Herbert of Muckross, County Kerry. In 1760 their daughter, Frances Jane, married Simon White of Bantry, William Henry’s grandfather. When her brother Robert Hedges Eyre died without heirs in 1840 his estates were divided and William Henry the 3rd Earl of Bantry inherited the Macroom estate. [4] Until his brother’s death in 1868, William Henry Hedges-White had been living in Macroom Castle. [5]

William Henry Hedges-White married Jane Herbert in 1845, daughter of Charles John Herbert of Muckross Abbey in County Kerry (see my entry about places to visit in County Kerry).

In November 1853, over 33,000 acres of the Bantry estate were offered for sale in the Encumbered Estates Court, and a separate sale disposed of Bere Island. The following year more than 6,000 further acres were sold, again through the Encumbered Estates Court. Nevertheless in the 1870s the third earl still owned 69,500 acres of land in County Cork.

His son, the 4th Earl, died childless in 1891. The title lapsed, and the estate passed to his nephew, Edward Egerton Leigh (1876-1920), the son of the 4th Earl’s oldest sister, Elizabeth Mary, who had married Egerton Leigh of Cheshire, England. This nephew, born Edward Egerton Leigh, added White to his surname upon his inheritance. He was only fifteen years old when he inherited, so his uncle Lord Ardilaun looked after the estate until Edward came of age in 1897. William Henry Hedges-White’s daughter Olivia Charlotte Hedges-White had married Arthur Edward Guinness, 1st and last Baron Ardilaun. Edward Egerton’s mother had died in 1880 when he was only four years old, and his father remarried in 1889.

Edward Egerton married Arethusa Flora Gartside Hawker in 1904. She was a cousin through his father’s second marriage. They had two daughters, Clodagh and Rachel. In March 1916 an offer from the Congested Districts’ Board was accepted by Edward Egerton Leigh White for 61,589 tenanted acres of the estate. [6] Edward Egerton died in 1920.

Patrick Comerford tells us in his blog that during the Irish Civil War in 1922-1923, the Cottage Hospital in Bantry was destroyed by fire. Arethusa Leigh-White offered Bantry House as a hospital to the nuns of the Convent of Mercy, who were running the hospital. Arethusa only made one proviso: that the injured on both sides of the conflict should be cared for. A chapel was set up in the library and the nuns and their patients moved in for five years. [7]

In 1926, Clodagh Leigh-White came of age and assumed responsibility for the estate. Later that year, she travelled to Zanzibar, Africa, where she met and married Geoffrey Shelswell, then the Assistant District Commissioner of Zanzibar. (see [7])

Geoffrey Shelswell added “White” to his surname when in 1926 Clodagh inherited Bantry estate after the death of her father. They had a son, Egerton Shelswell-White (1933-2012), and two daughters, Delia and Oonagh.

During the Second World War, the house and stables were occupied by the Second Cyclist Squadron of the Irish Army, and they brought electricity and the telephone to the estate.

Clodagh opened the house in 1946 to paying visitors with the help of her sister Rachel who lived nearby. Her daughter Oonagh moved with her family into the Stable Yard.

Clodagh remained living in the house after her husband died in 1962, until her death in 1978. Brigittte, wife of Clodagh’s son Egerton, writes:

“As far as I know it never occurred to Clodagh to live elsewhere. She thought nothing of having her sitting room downstairs, her kitchen and bedroom upstairs and her bathroom across the landing. No en suite for her! In the winter when the freezing wing howled through the house, she more or less lived in her fur coat, by all accounts cheerful and contented. She loved bridge and held parties, which took place in the Rose Drawing Room, or in the room next to the kitchen, called the Morning Room.“

Brigitte also tells of wonderful evenings of music and dance hosted by Clodagh and her friend Ian Montague, who had been a ballet dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet. Ian put on plays and dancing in period costumes. Members of the audience were taught about eighteenth century dance and were encouraged to join in. I think we should hold such dances in the lovely octagon room of the Irish Georgian Society!

Clodagh’s son Egerton had moved to the United States with his wife Jill, where he taught in a school called Indian Springs. When his mother died he returned to Bantry. The house was in poor repair, the roof leaking and both wings derelict. Jill decided to remain in the United States with their children who were teenagers at the time and settled into their life there.

Bantry House features in Great Irish Houses, which has a foreward by Desmond FitzGerald and Desmond Guinness (IMAGE Publications, 2008). In the book, Egerton is interviewed. He tells us:

p. 68. “The family don’t go into the public rooms very much. We live in the self-contained area. I remember before the war as children we used the dining rooms and the state bedrooms, but after the war my parents moved into this private area of the house. It feels like home and the other rooms are our business. You never think of all that furniture as being your own. You think of it more as the assets of the company.”

The relatively modest private living quarters were completed in 1985. Sophie Shelswell-White, Egerton’s daughter, says, “When we were younger we shied away from the main house because of the intrusion from the public. Everyone imagines we play hide and seek all day long and we did play it a bit. We also used to run around looking for secret tunnels and passageways. I used to believe one day I’d push something and it would open a secret room, but it never happened.”

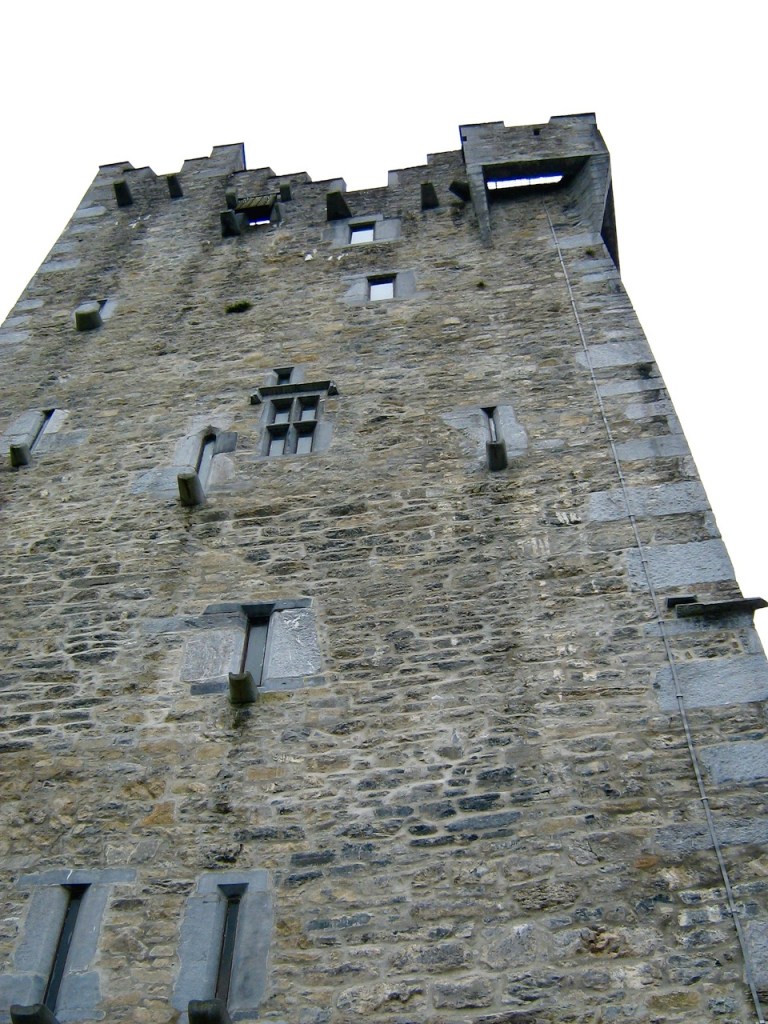

Mark Bence-Jones continues his description, moving to the stables: “Flanking the entrance front is an imposing stable range, with a pediment and cupola. The house is surrounded by Italian gardens with balustrades and statues and has a magnificent view over Bantry Bay to the mountains on the far shore. The demesne is entered by a fine archway.” (see [2])

The National Inventory tells us about the East Stables:

“A classically inspired outbuilding forming part of an architectural set-piece, the formal design of which dates to the middle of the nineteenth century when Richard White, Viscount Berehaven and later second Earl of Bantry, undertook a large remodelling of Bantry House. At this time the house was extended laterally with flanking six-bay wings that overlook the bay. This stable block and the pair to the south-west are sited to appear as further lateral extensions of the house beyond its wings; when viewed from the bay they might be read as lower flanking wings in the Palladian manner. This elaborate architectural scheme exhibits many finely crafted features including a distinguished cupola, playful sculptural detailing as well as cut stone pilasters to the façade. The survival of early materials is visible in a variety of fine timber sliding sash windows, which add to the history of the site.“

Egerton married Brigitte in 1981. They undertook many of the repairs themselves. They started a tearoom with the help of a friend, Abi Sutton, who also helped with the house. Egerton played the trombone and opened the house to musical events. They continued to open the house for tours. They renovated the went wing and opened it for bed and breakfast guests.

Coffee is served on the terrace, similar to that in the front, but only partly glazed. Unfortunately we arrived too late for a snack. Bantry House is breathtaking and its gardens and location magnify the grandeur. I like that the grandeur, like Curraghmore, is slightly faded: a lady’s fox fur worn down to the leather and shiny in places.

The balustraded area on the side of the house where tea and coffee are served overlooks a garden.

Brigitte and Egerton continued restoration of the house and started to tackle the garden. They repaired the fountain and started work on the Italian parterre. In 1998 they applied for an EEC grant for renovation of the garden. They restored the statues, balustrades, 100 Steps, Parterre, Diana’s Bed and fourteen round beds overlooking the sea.

It is Egerton’s daughter Sophie who now lives in and maintains Bantry House, along with her husband and children.

The family donated their archive of papers to the Boole Library of University College Cork in 1997.

The National Inventory tells us the five-bay two-storey west stables were also built c.1845. They have a pedimented central bay with cupola above, which has a copper dome, finial, plinth and six Tuscan-Corinthian columns. [8] The West Stables were used as a workshop for outdoor maintenance and repairs. They had fallen into disrepair but were repaired to rectify deteriorating elements with the help of the Heritage Council in 2010-11.

[1] https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-theobald-wolfe-a8590

[2] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[3] https://theirishaesthete.com/2014/09/08/when-its-gone-its-gone/

[4] https://landedestates.ie/family/1088 and https://www.dib.ie/biography/eyre-robert-hedges-a2978

See also

[5] Shelswell-White, Sophie. Bantry House & Garden, The History of a family home in Ireland. This booklet includes an article by Geoffrey Shelswell-White, “The Story of Bantry House” which had appeared in the Irish Tatler and Sketch, May 1951.

[6] https://landedestates.ie/family/1088

[7] http://www.patrickcomerford.com/2016/05/bantry-house-has-story-that-spans.html

© Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com