Wells House, County Wexford

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is my “full time job” and created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated! My costs include travelling to our destinations from Dublin, accommodation if we need to stay somewhere nearby, and entrance fees. Your donation could also help with the cost of the occasional book I buy for research (though I mostly use the library – thank you Kevin Street library!). Your donation could also help with my Irish Georgian Society membership or attendance for talks and lectures, or the Historic Houses of Ireland annual conference in Maynooth.

€15.00

2026 Diary of Irish Historic Houses (section 482 properties)

To purchase an A5 size 2026 Diary of Historic Houses send your postal address to jennifer.baggot@gmail.com along with €20 via this payment button. The calendar of 84 pages includes space for writing your appointments as well as photographs of the historic houses. The price includes postage within Ireland. Postage to U.S. is a further €11 for the A5 size, so I would appreciate a donation toward the postage – you can click on the donation link.

€20.00

Donation towards accommodation

I receive no funding nor aid to create and maintain this website, it is a labour of love. I travel all over Ireland to visit Section 482 properties and sometimes this entails an overnight stay. A donation would help to fund my accommodation.

€150.00

Wells House, although not a Section 482 property, is open to the public for house tours and has 450 acres of woodland and garden to explore. It is one of Wexford’s most popular tourist destinations with some 100,000 visitors each year. Stephen and I visited in May 2025.

The original house was built in the 1600s for John Warren, a Cromwellian soldier who was granted 6000 acres. The house at the time was a simple square manor. The name “Wells” comes from the fact that the land holds several natural springs. In the 1830s Daniel Robertson enlarged and remodelled the house in Tudor-Gothic style.

According to the house’s website, John Warren’s wife predeceased him and he had no children. In his last will and testament, he left his estate, which was then earning him £400 a year, to a cousin, Hugh Warren, on the condition that Hugh pay Samuel Jackson, the executor, £5000, to be divided among John’s other relatives. Alternatively, if Hugh preferred, Wells would be sold, and he would instead be given £500.

Hugh was at Wells in 1693 when John Warren died. He immediately collected up all the valuables in the house, including £1200. He then opted for the £500 legacy rather than having to pay £5000 to inherit the house.

The executor of the will, Samuel Jackson, must have realised that Warren had taken things from the house, so took Hugh to court in England, which resulted in Hugh being imprisoned in 1699.

The House of Lords was asked to delibrate on the case, and two years later Hugh was released from primson but he was ordered to sell the house. [1]

The estate was purchased in 1703 by Robert Doyne (1651-1733). At the time, Robert Doyne was Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas in Ireland, having studied in Trinity College Dublin.

The tour guide, Aileen, told us that Robert Doyne was from an old Irish family from County Laois. He never lived in the seventeenth century house, and nor did his son and heir, Philip (1685-1753). Robert married Jane, widow of Joseph Saunders of Saunders Court in County Wexford and daughter of the wealthy lawyer and politician Henry Whitfield. They had a house in Dublin at Ormond Quay, where he died, and he is buried in St. Nicholas Within in Dublin. [2]

The son Philip, who served on the Privy Council, married three times. His first wife, Mary, was daughter of Benjamin Burton (1662-1758), MP for Dublin and Lord Mayor of Dublin, who purchased Burton Hall in County Carlow. Mary gave birth to Philip’s heir, Robert (1705-1754) but she died in childbirth.

Philip went on to marry Frances South, with whom he had several children. Their son Charles (d. 1777) held the office of Dean of Leighlin. Frances died in 1712, and Philip married his third wife, Elizabeth, daughter of James Stopford, MP for County Wexford. Elizabeth’s brother was James, 1st Earl of Courtown, County Wexford.

The tour guide told us that it was Robert Doyne’s great grandson who inherited the property when he was just nine years old, another Robert Doyne, who had Wells House rebuilt, designed by Daniel Robertson.

To backtrack to look at the family tree, Philip Doyne and Mary Burton’s son Robert (1705-1754) inherited the estate and old house at Wells. He served as MP for County Wexford and also High Sheriff. He married Deborah Annesley.

Their son Robert (1738-1791) also served as High Sheriff for County Wexford. His elder brother Philip married Joanna, daughter of Arthur Gore 1st Earl of Arran, but he died young and they had no children. Robert married Mary Ram from Ramsfort in County Wexford, whose father Humphreys was also an MP.

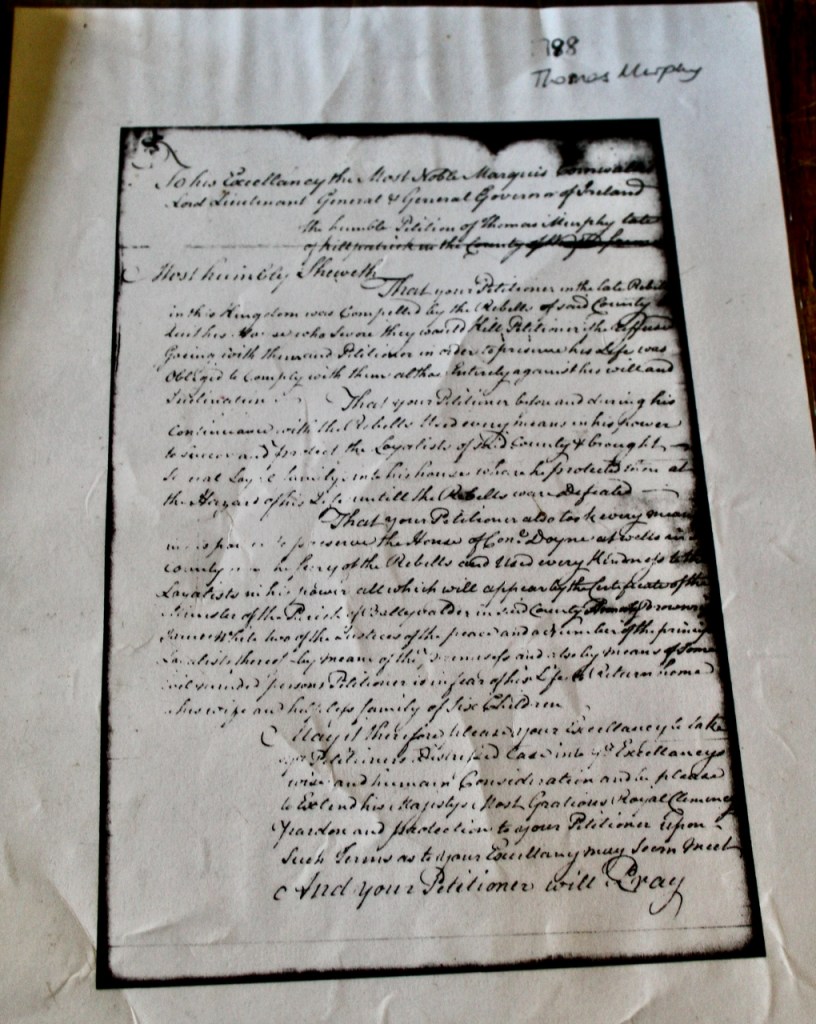

Wells House was spared from attack in the 1798 Rebellion thanks to protection by a local man, Thomas Murphy, who claimed to have risked his life to save the house. Tour Guide Aileen showed us a copy of the letter in which he makes this claim, when he sought to be exonerated from his part in the 1798 Rebellion.

Wells House became a barracks for the troops that were stationed in the area after the fighting of 1798. The house’s website blog tells us:

“They occupied it for three years. Once the army left, the house and 393 acres around it were let, on long-term lease, to a man named Charles Craven for £393 a year. Craven carried out repairs to the house, and set about improving the land, but in 1811 Robert Doyne, who had by this time left school in Dublin, moved to England, married and decided he would return to Wells to live. To compensate Charles Craven for the work he had done, he agreed to pay the Cravens £80 a year for as long as Charles or his son should live.“

Robert and Mary Ram’s son Robert (1782-1850) married Annette Constantia Beresford in 1805. Before that he’d lived a life of adventure, travelling in Europe with famous dandy Beau Brummell, sailing on a raft down the Rhine. We came across Annette Constantia Beresford when we visited Woodhouse in County Waterford. She had been married to Colonel Robert Uniacke (1756-1802) of Woodhouse, County Waterford (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2025/03/29/woodhouse-county-waterford-private-house-tourist-accommodation-in-gate-lodge-and-cottages/ ).

It was Robert (1782-1850), probably with wealth from his wife’s first marriage, who commissioned Daniel Robertson to design the Wells House which we see today, building on to the original square residence.

Mark Bence-Jones writes (1988):

“(Doyne/IFR) A Tudor-Gothic house of ca 1840 by Daniel Robertson of Kilkenny; built for Robert Doyne, replacing an earlier house which, for nearly three years after the Rebellion of 1798, was used as a military barracks. Gabled front, symmetrical except that there is a three sided oriel at one end of the façade and not at the other, facing along straight avenue of trees to entrance gate. Sold ca 1964.” [3]

The house is of red brick with granite dressings, and has finial topped gables on the roofline. A crenellated Tudor style entrance porch with arched entrance surrounds the studded timber door. Windows have arched tops, Gothic tracery and hood moulding. The oriel window has crenellation on top.

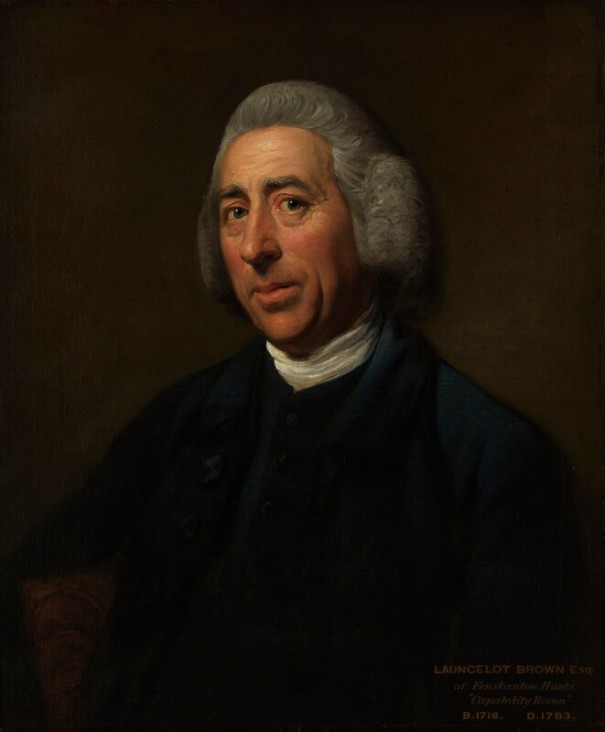

Robertson, our guide told us, was born in America. When living in England he was thrown into debtors prison. He then moved to Ireland, and Wells was one of his first Irish commissions. He lived in Wells House while working on Johnstown Castle nearby (see my entry about Johnstown Castle https://irishhistorichouses.com/2023/09/30/a-heritage-trust-property-johnstown-castle-county-wexford/). He worked for the Doyne family on and off for fourteen years and he designed everything from the house, gardens, window sills down to such detail as the picture frames.

We came across Daniel Robertson’s architectural work also when we stayed at Wilton Castle in County Wexford (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2022/02/04/wilton-castle-bree-enniscorthy-co-wexford-and-a-trip-to-johnstown-castle/).

The Dictionary of Irish Architects tells us more about Daniel Robertson:

“From the early 1830s he did no further work in Britain but received a series of commissions in Ireland, mainly for country house work in the south eastern counties. Most of these houses or additions were in the Tudor style, which, he asserted in a letter to a client, Henry Faulkner, of Castletown, Co. Carlow, was ‘still so new and so little understood in Ireland’. For some of them he used Martin Day as his executant architect.” [4]

Daniel Robertson introduced a dramatic entrance avenue of oaks in the 1840s, retaining the original U shape directly in front of the house. Some of the original oak trees remain, which are over two hundred years old. Lady Frances planted fifty species of daffodil on the avenue.

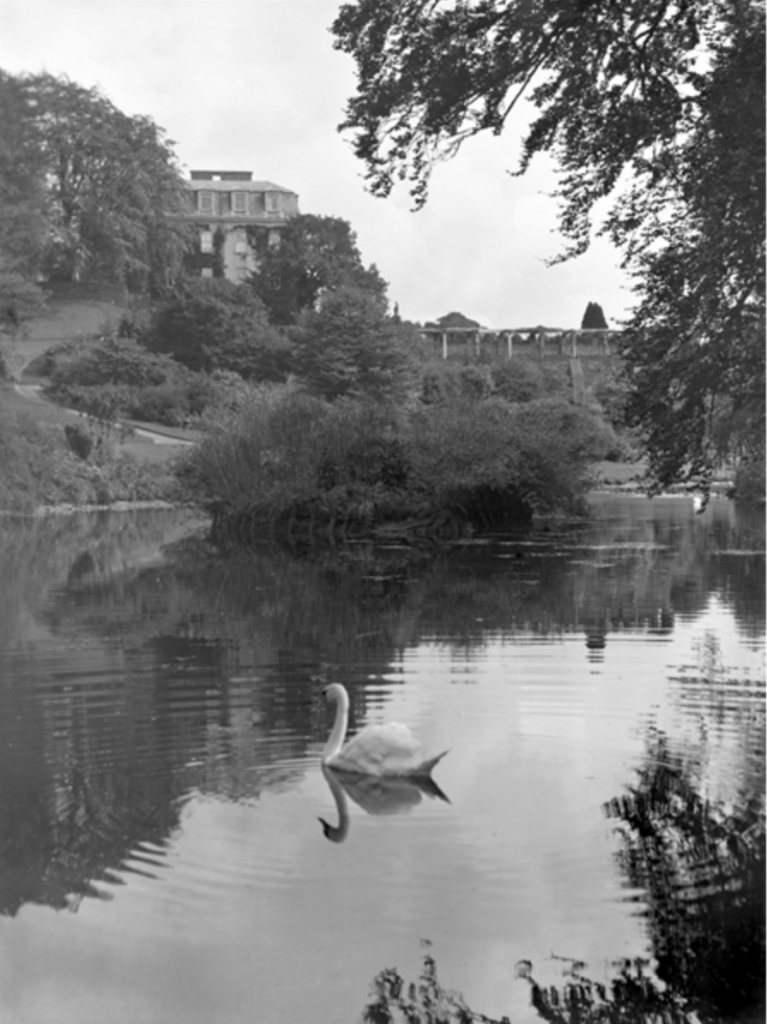

The avenue is 550 meters in length from the front door to the entrance at the road and this central axis continues through the house and finishes at a lake that is situated in the woodland at the far side of the house.

Along the avenue on the left-hand side, the website tells us, are 25 mature Oak trees, 3 Sycamore, 2 Lime, and one beech tree. Amongst them we have a Champion Oak tree. A champion tree is the largest tree of a species. [5]

Robertson also designed the surrounding garden including the parterre at the back of the house. From the French word meaning ‘on the ground’, a parterre is a formal garden laid out on a level area and made up of enclosed beds, separated by gravel. Parterres often include box hedging surrounding colourful flower beds.

The parterre was first developed in France by garden designer Claude Mollet around 1595 when he introduced compartment-patterned parterres to royal gardens at Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Fontainebleau. The style soon became popular in France and all over Europe. [6]

Robert O’Byrne tells us that Daniel Robertson was one of the most influential garden designers to work in Ireland in the second quarter of the 19th century.

From 1842 onwards, the 6th Viscount of Powerscourt employed Daniel Robertson to improve the gardens (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/04/26/powerscourt-house-gardens-enniskerry-county-wicklow/). Robertson created Italian gardens on the terraces, with broad steps and inlaid pavement, balustrades and statues.

The Dictionary of Irish Architects continues in the entry about Robertson: “In spite of his success in attracting commissions, when he was working at Powerscourt in the early 1840s he was, in the words of Lord Powerscourt, ‘always in debt and…used to hide in the domes of the roof of the house’ to escape the Sheriff’s officers who pursued him. By then he was crippled with gout and in an advanced state of alcoholism; at Powerscourt he ‘used to be wheeled out on the terrace in a wheelbarrow with a bottle of sherry, and as long as that lasted he was able to design and direct the workmen, but when the sherry was finished he collapsed and was incapable of working till the drunken fit had evaporated.’ In at least two instances – at Powerscourt and at Lisnavagh – he lived on the premises while work was in progress, and it seems that from the 1830s until the year of his death his wife and family never settled for any time in Ireland… Robertson was overseeing the completion of Lisnavagh, Co. Carlow, where he had been living intermittently since the start of building in 1846, when he fell seriously ill in the spring of 1849” and died in September of that year. [see 4]

Our guide brought us through the impressive double door into the entrance hall. The vestibule retains its original encaustic tile floor, and carved timber Classical-style surrounds to door openings and windows with their shutters. [7]

Daniel Robertson imported Italian oak for the panelling in the entrance hall. The hall retains its carved timber Classical-style corner chimneypiece, and dentilated cornice to the compartmentalised ceiling.

The ceiling of the entrance hall has the carved coat of arms of the Doynes, with an eagle representing strength and courage, and the family motto Mullac a boo, “Victory from the hills.”

There is more carved decoration above the door from the vestibule.

Robert and Annette Constantia’s son Robert Stephen Doyne (1806-1870) lived at Wells House. He served as High Sheriff of County Wexford and later of County Carlow, and was Deputy Lieutenant and Justice of the Peace. He married Sarah Emily Tynte Pratt (1814-1871), daughter of Joseph Pratt (1775-1863) of Cabra Castle.

Robert Stephen Doyne’s son Charles Mervyn Doyne (1839-1924) was heir to the estate. He attended university in Magdalene College in Cambridge, then served, like his father, as High Sheriff of Counties Wexford and Carlow, Justice of the Peace and Deputy Lieutenant.

In Cambridge he met the sons of William Thomas Spencer Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, 6th Earl Fitzwilliam of the grand house Wentworth Woodhouse in England. The family was one of the richest in England, and made their money from mining coal on their 20,000-acre estate near Sheffield in Yorkshire. They also owned Coollattin in County Wicklow, and the 6th Earl served as M.P. for Wicklow between 1847 and 1857.

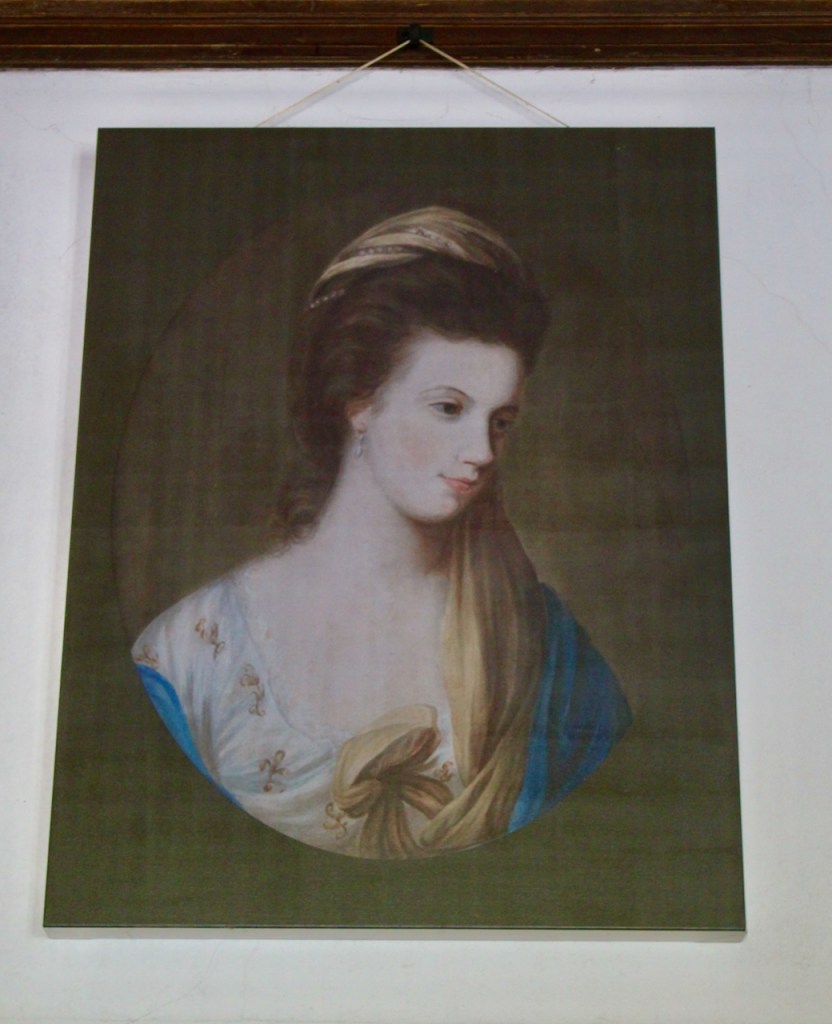

Charles Mervyn stayed with the family at Coollattin, playing cricket, shooting and fishing, and there met his friends’ sister, his wife-to-be, Lady Frances. He and Lady Frances announced their engagement in September 1867 and married two months later at Wentworth Woodhouse. [8]

Our tour mostly focussed on the lives of Charles Mervyn and his wife, because they lived in and clearly loved Wells House. They were good landlords and had twelve servants, all of whom could read and write. Interestingly, they gave their daughters rather Irish names: Kathleen, Eveleen and Bridget.

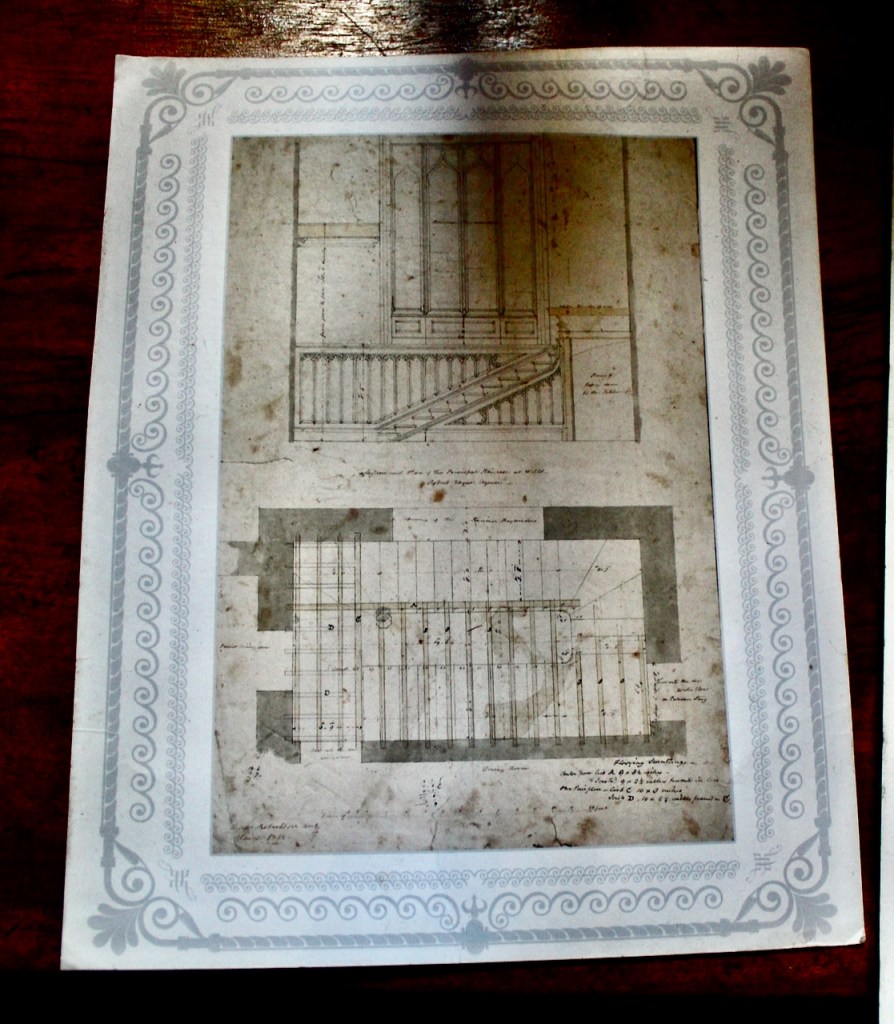

We passed through a stair hall next to the large entrance hall, which contains the original staircase of the seventeenth century house.

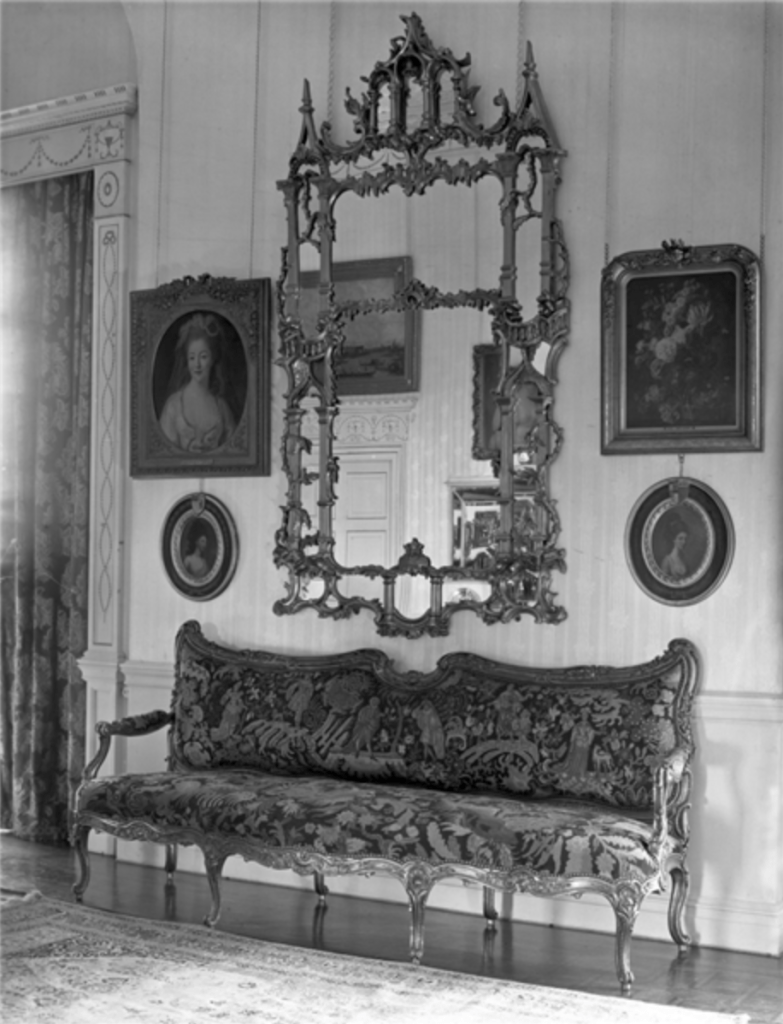

The Drawing Room is the piéce de resistance of the house with its Versailles style. The room has a cut white marble corner Classic-style chimneypiece with large mirror over, and decorative wall panelling.

An impressive gilt acanthus leaf ceiling rose with surrounding leaf decoration support a chandelier, and the room has a modillion cornice and a border with acanthus detail.

A musical decoration indicates that the room was probably used for musical events. The female face in the panel shows that this was the Ladies Drawing Room, with romantic Cupid’s sheaf of arrows.

The timber panelled door has carved surround matching shutters and window surrounds, and matching pelmets. The door decoration is repeated in the wall panels.

The dining room reminded me of Johnstown Castle, with its carved timber geometric ceiling and Gothic-style timber panelled wainscoting.

A secret room was disovered over one of the doors entering the dining room, where Charles Doyne’s weapons were hidden.

The dining room has what the National Inventory refers to as a “Tudor-headed” buffet niche.

Aileen showed us the two surprising places where food entered the room – through a trap door in the floor and through a grate in the fireplace! There is a room you can see through the grate where food preparation took place.

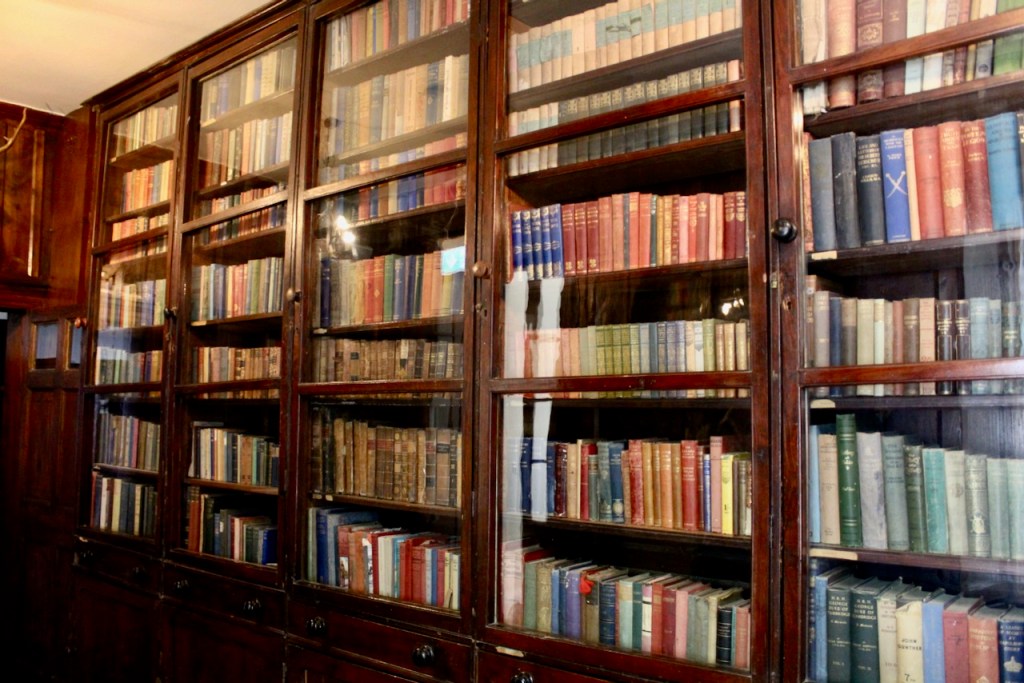

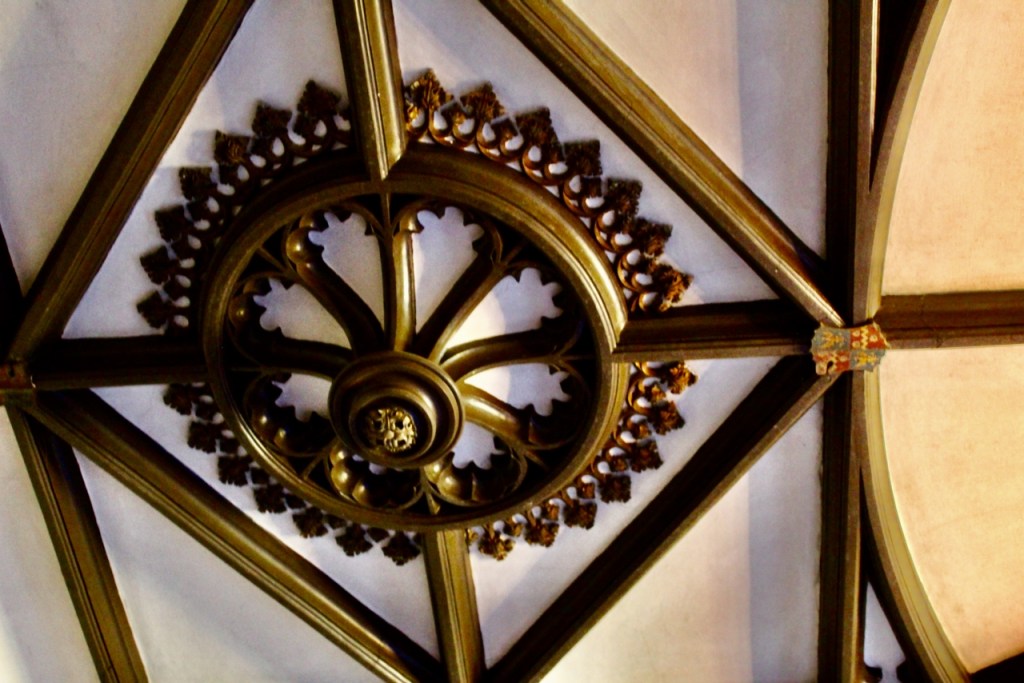

The study has jib doors hidden within the bookcases, disguised by false books. It has a carved timber Gothic-style corner chimneypiece, and carved timber cornice to the geometric ceiling centred on Gothic-style ceiling rose.

Robert, Charles’s son, started a lending library based on his book collection. Some of the original books that belonged to the Doynes remain in the collection.

The study, or Fossil Room as it was called, is the cabinet of curiosities of items collected by the family on their travels. The room has another corner marble fireplace and timber cornice with geometric decorative ceiling with armourial shields.

Lady Frances painted the pictures that hang on the walls of the fossil room. She died of scarlet fever in 1903, and her husband lived another 21 years but never remarried.

The stair hall introduced in the Robertson renovation has more Gothic timber wainscoting, and cast iron balusters support a carved timber banister which terminates in octagonal newels. The half-landing has the oriel window with stained glass detail and carved shutters. The groin vaulted ceiling has moulded plasterwork ribs centred on octagonal boss. I found it hard to capture the grandeur in one photograph!

We visited two bedrooms upstairs. Our guide explained that the beds were made shorter in those days, because a sleeper slept sitting up in order to breathe better. The fireplace in the room would have absorbed oxygen from the air so it was easier to breathe in an upright position.

Electricity wasn’t installed until the 1950s.

When the Butler was ill, Charles Doyle sent for his own doctor. The doctor advised that the Butler take some time off work. When the Butler died just one day after he went home to his family, Charles was heartbroken, our guide told us. The family were good to their servants and tenants. They ran a soup kitchen during the Famine.

Frances enjoyed horseriding, and the house still has her riding habit.

Charles and Frances’s son Robert married Mary Diana Lascelles, daughter of Henry Thynne Lascelles, 4th Earl of Harwood. He chose to sell the house. His sister Kathleen, who never married, bought it!

When Kathleen died in 1938, her brother Dermot inherited, and gave the house to his son Charles Hastings Doyne. Charles Hastings sold the house to a German family, who renovated it. It was opened to the public in 2012.

It was for sale again in 2019 and purchased in 2022 by a local man. He renovated the outbuildings for tourist accommodation.

The property has a café, playground, woodland walk, a glorious walled garden and small menagerie of animals, and is a working farm.

In the menagerie of animals we were especially delighted with the meerkats who had fun sliding down a slide!

[1] https://wellshouse.ie/a-tale-of-betrayal-and-treachery-at-wells

[2] F. Elrington Ball, The Judges in Ireland 1221-1921 published by John Murray, London, 1926.

[3] p. 283, Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://www.dia.ie/architects/view/4570/ROBERTSON%2C+DANIEL#tab_biography

[5] https://wellshouse.ie/a-wells-house-country-garden-our-champion-oak

[6] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/perfect-parterres/

[7] https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/15702132/wells-house-wells-co-wexford