donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

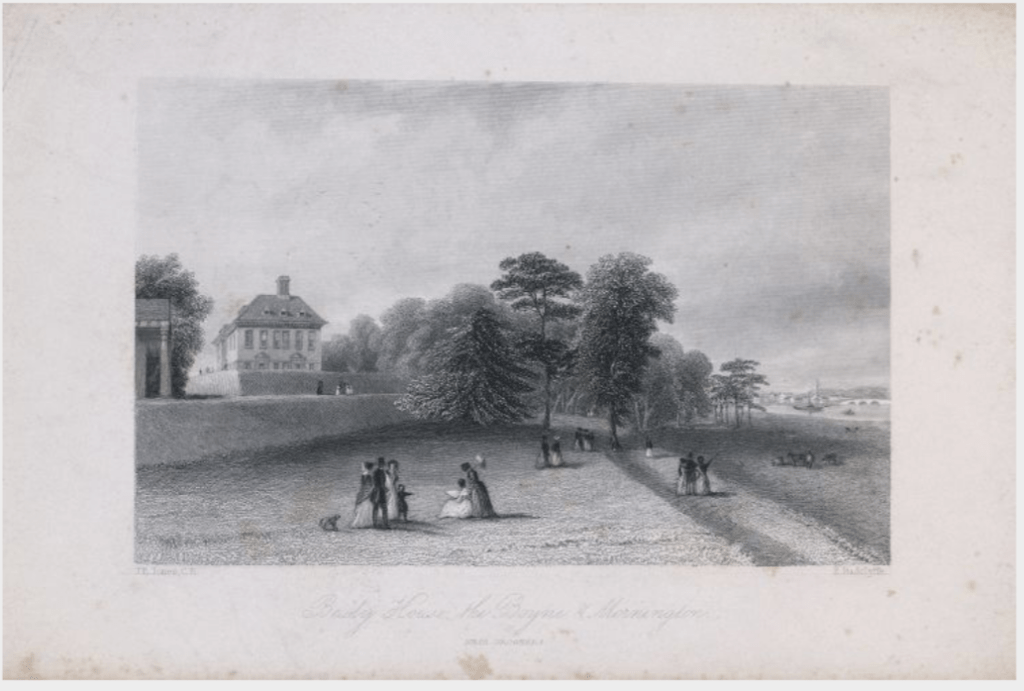

Beaulieu House, near Drogheda in County Louth, is not on the Section 482 list in 2019 or 2020, for the first time in many years. I visited, however, during Heritage Week in 2019, and it’s definitely worth a write-up. The front hall is magnificent, and the history of the house is a lesson in the history of Ireland. The history of Beaulieu encompasses the history of Ireland from the 1640s and its owners played an active role.

It is pronounced “Bewley” and sometimes written on earlier maps as “Bewly.” Nobody is sure where the name came from, but the website suggests that it may come from “booley,” the practice of the Irish in which cattle are moved from place to place to graze. It could of course be after the French for lovely place.

The house overlooks the River Boyne – you can see it beyond the garden at the side of the house:

Beaulieu is a very important house architecturally as it is one of the few Dutch influenced houses still surviving, in a style deriving from works of Inigo Jones. It was built around 1715 and incorporates an older building. The Irish Aesthete tells us that the architect was probably John Curle. [1] The Dictionary of Irish Architects tells us that John Curle may have come originally from Scotland, and was active in Counties Fermanagh, Louth, Meath and Monaghan in the late 1690s and first quarter of the 1700s. As well as working on Beaulieu, he designed the original house at Castle Coole, Co. Fermanagh, built in 1709, and in about 1709 he designed Conyngham Hall (later Slane Castle), Co. Meath (another Section 482 property). It has also been suggested that Curle also designed Stackallan House, Co. Meath, in 1712.

Cement-rendered with redbrick trim, Beaulieu has two show facades, the west front and the south garden front. The entrance is of seven bays, with the two end bays brought forward. The windows are framed with flat brick surrounds, and the doorcase, of brick, consists of two Corinthian pilasters supporting a large pediment with carved swags.

There are three dormer windows over the centre three bays, and one above each two-bay projection, and this type of dormer window is a classical mid-seventeenth century practice of construction. [2] The high eaved roof is carried on a massive wooden modillion cornice. Modillions are small consoles at regular intervals along the underside of some types of classical cornice.

The two tall moulded chimneystacks are also of brick. [3] There is a single-storey projecting billiard room in the back and a canted bay which I did not see, on the east side. [4]

The garden front is a six-bay elevation with two doorcases, one in the centre of each principal room, both with Ionic pilasters and crowned with large triangular pediments. It looks as though the doors open by lifting upwards on a sash, like the door/window we saw at Corravahan in County Cavan.

This side of the building has three dormer windows.

Beaulieu is now owned by Cara Konig-Brock, who inherited it in from her mother Gabriel de Freitas, who was the tenth generation of descendants since King Charles II granted the lands to Henry Tichbourne in 1666. Gabriel inherited the house from mother, Sidney nee Montgomery, who was married to Nesbit Waddington. [5] The house is unusual in that it has often passed through the female rather than male line.

We arrived early for the tour, so wandered the gardens first. We were excited to see the ramshackle remnants of a festival in the wooded part of the back garden – Vantastival takes place at Beaulieu. I love the magic, creativity and craftsmanship of the pop-up structures in the woods.

There was even a boat in the garden, I assume left over from the festival:

But before I discuss the garden, I’ll tell you about the tour and the house, to give a bit of perspective.

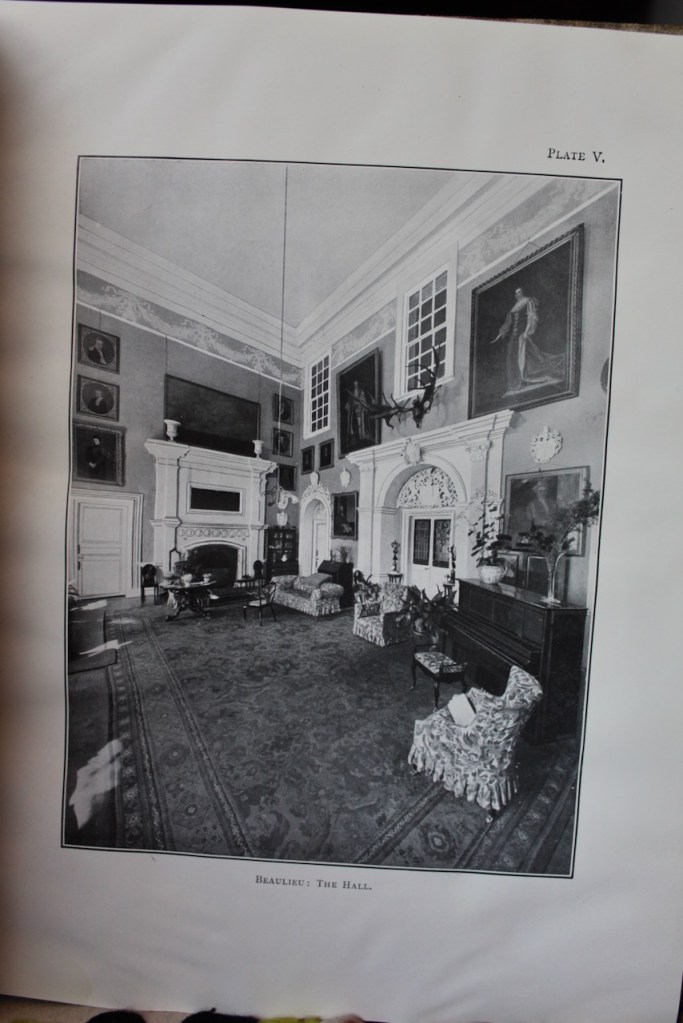

We were greeted by a guide when it was time to enter the house. The front hall which we entered is impressive and rather worn with age. It is double height, and I found it difficult to take in everything at once; when overwhelmed, I focus on one thing – in this case it was the couch. I was delighted to be invited sit in front of the huge fireplace to start the tour, to be able to take in my surroundings. Our guide told us we could take photographs as long as we don’t take pictures of the paintings. It was hard to take photographs, however, without including the paintings, as they covered the walls! So I didn’t take many photos, unfortunately. The large two storey hall is a late seventeenth century copy of a medieval hall.

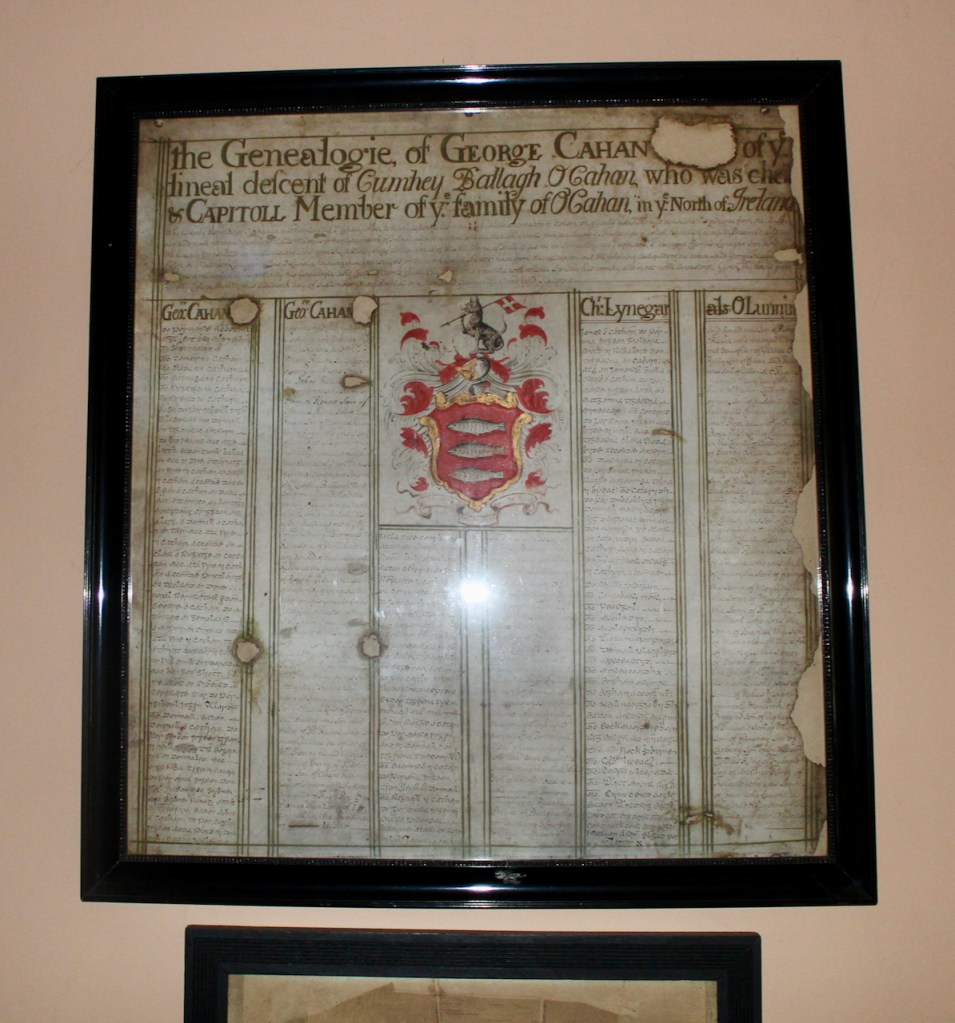

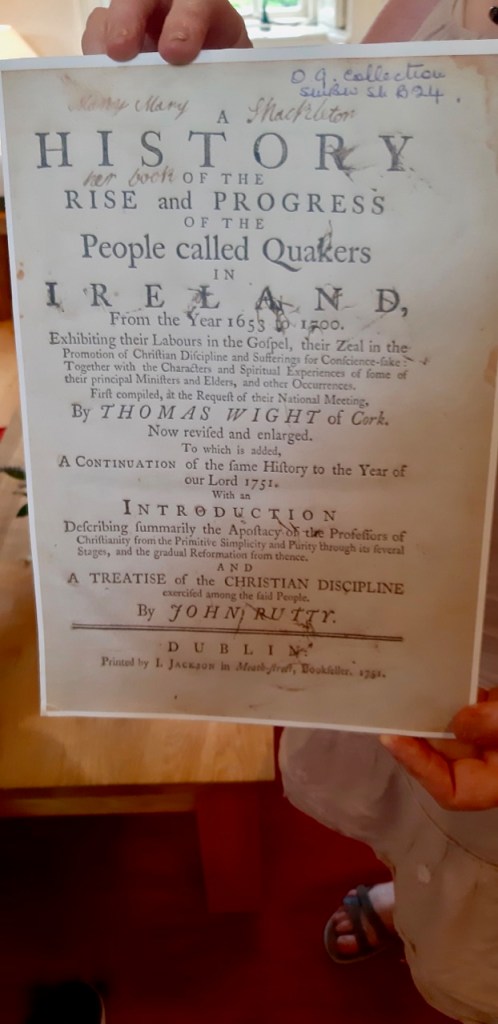

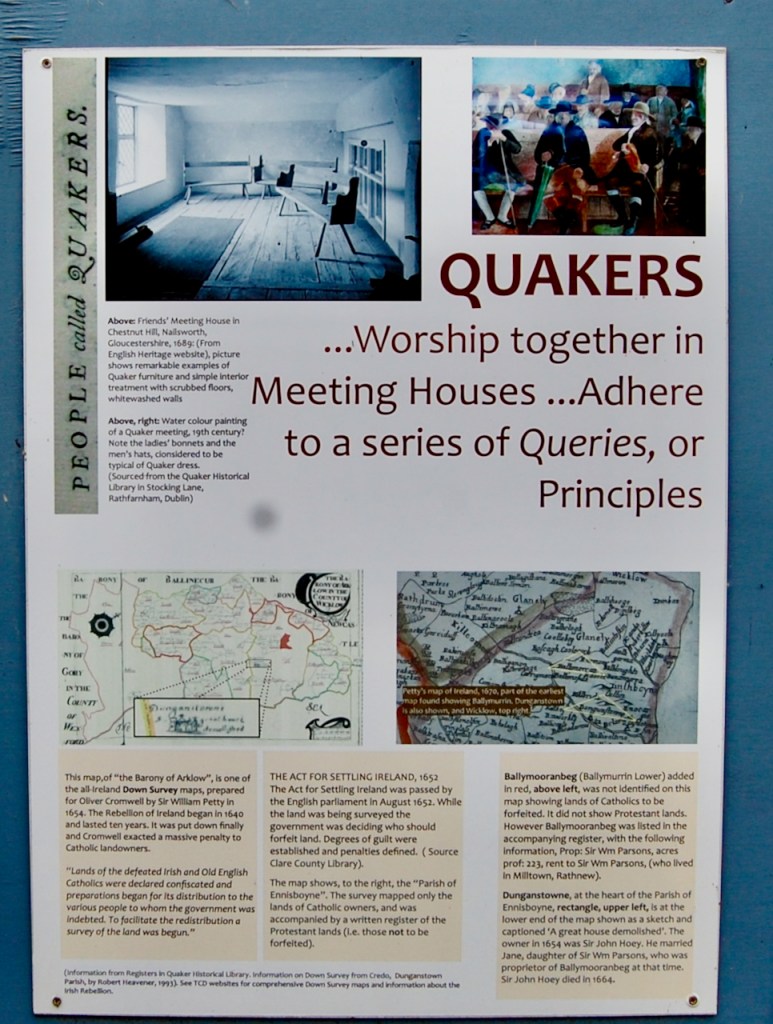

Before Henry Tichbourne, who acquired it around 1666, the land was owned by the Plunketts. According to the Beaulieu website, the Plunkett family may have first inhabited a tower house at the location. I came across the Plunketts when we visited Dunsany Castle, another Section 482 property. Sir Hugh de Plunkett, an Anglo-Norman, came to Ireland during the reign of Henry II. From then on the family owned lands in Louth and Meath. In 1418 Walter Plunkett obtained royal confirmation of his rights in Bewley and other land. [6] Christopher and Oliver Plunkett, the 6th Baron of Louth (1607-1679) took part in the 1641 Rebellion, and were outlawed. [7] The wide walls of the original tower house can be found in the fabric of the building today. [8] Our guide described these walls: rather contrary to expectations, the walls get thicker higher up. This makes sense if you consider that cannonballs would hit the upper part of a structure.

According to Mark Bence-Jones, it is one of the first country houses built in Ireland without fortification, although until the 19th century it was surrounded by a tall protective hedge, or palisade. [9] Also, the front door is hung with massive carved oak and iron studded shutters, which Bence-Jones explains are probably a vestige of military protection. We did not see these shutters as the door was open for visitors. In the 17th century, troops were garrisoned in the house for a time. We learned more about these troops during the tour.

A History of Beaulieu is a History of Ireland in the 1600’s

To begin chronologically, it’s best to start in 1641 during Phelim O’Neill’s uprising against the British. Phelim O’Neill (1604-1653) rose up to try to prevent a second wave of Plantation in Ireland. During the plantations, first in Laois and Offaly and then in Ulster, lands were taken from the native Irish and given to Protestant settlers to farm, in order to firm up the English King’s control in Ireland. Richard Plunkett, who owned the land at Beaulieu at the time and was a colonel in Phelim O’Neill’s army, allowed Phelim to station his troops in his fortified dwelling at Beaulieu. In his fight, Phelim attacked the walled city of Drogheda.

Henry Tichbourne (or Tichborne – different reference sources spell the name differently) at this time was governor of Lifford, County Donegal. [10] He had come to Ireland from England where as a younger son of Benjamin the 1st Baronet Tichborne of Titchborne, Co. Southampton, he had joined the military. He became commissioner for the Plantation of County Londonderry. Tichborne was sent to Drogheda to protect the city from Phelim O’Neill and his followers. Henry saved the city of Drogheda. His victory is celebrated in the incredible intricately carved wooden “trophy” over the front door in Beaulieu, which includes the “Barbican gate” of Drogheda, underneath the armoured soldier:

According to our guide, after the battle with Phelim O’Neill, the house at Beaulieu was left empty, and Henry Tichbourne moved in. Later, he purchased the land from the Plunketts. The Plunketts had mortgaged their land in order to raise funds for the rebellion of 1641. Tichbourne was able to take over the mortgages and pay them, and thus acquire the estate, thus buying the land and tower that had been formerly occupied by his enemies. [11]

In 1642 King Charles I appointed Tichbourne Lord Justice of Ireland, and he held office until January 1644. In 1644 he went to England with the aim of negotiating peace between the King and the Irish Confederacy. James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde, came to the aid of Tichbourne in Drogheda in 1642. This could explain why Tichbourne was involved with trying to negotiate an agreement between King Charles and the Confederates, as Ormonde was a leading negotiator. [12] Complications arose because at the same time, the Puritans were gaining support in the Parliament in England. They judged Charles I to be betraying his religion and his people. Tichbourne sided with Charles I. He was captured by Parliamentary forces and spent some months as a prisoner in the Tower of London.

Upon his release, he returned to Drogheda. When Oliver Cromwell and his troops came to Ireland in 1649 they laid siege to Drogheda. Tichborne decided that the Royalists could not retain control of Ireland, and decided to join Cromwell’s side, the “Parliamentarians.” When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1661, he forgave Tichborne for his submission to the Parliament loyal to Oliver Cromwell. Charles II was very forgiving. (see Antonia Fraser’s excellent biography of Charles II. Fraser, incidentally, grew up in another house on the Section 482 list, Tullynally.) Charles II confirmed Henry Tichbourne’s ownership of Beaulieu in 1666, and made Tichbourne Marshall of the Irish Army. [13]

The painting in the chimneypiece in the Hall is of Drogheda after Cromwell’s siege. Henry Tichbourne, the grandson of the Tichbourne who fought at Drogheda, commissioned Willem Van Der Hagen to paint a port-scape of Drogheda in the early 1720s. Van Der Hagen began a painting career in Ireland around 1718. He began by painting sets at the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin – a theatre which has been re-established today after years of alternative use – and went on to become a founding father of Irish landscape painting. The panel painting is built into the overmantel, a picture that refers to Henry’s grandfather the military commander. It is a landscape of Drogheda, with, as the website describes: “its Cromwell-bombarded, medieval walls, gabled houses, (Dutch billies), numerous towers, gates, church spires, monastery gardens and a famous double barbican.”

Beaulieu House

Henry’s son William Tichborne was knighted in 1661 and sat in the Irish Parliament for the borough of Swords, 1661-1666. He was attainted by the Irish Parliament of King James II but was not dispossessed of his estates. He was M.P. for County Louth from 1692 until he died in 1693. He was married to Judith, daughter and co-heiress of John Bysse, Chief Baron of the Exchequer in Ireland. [14]

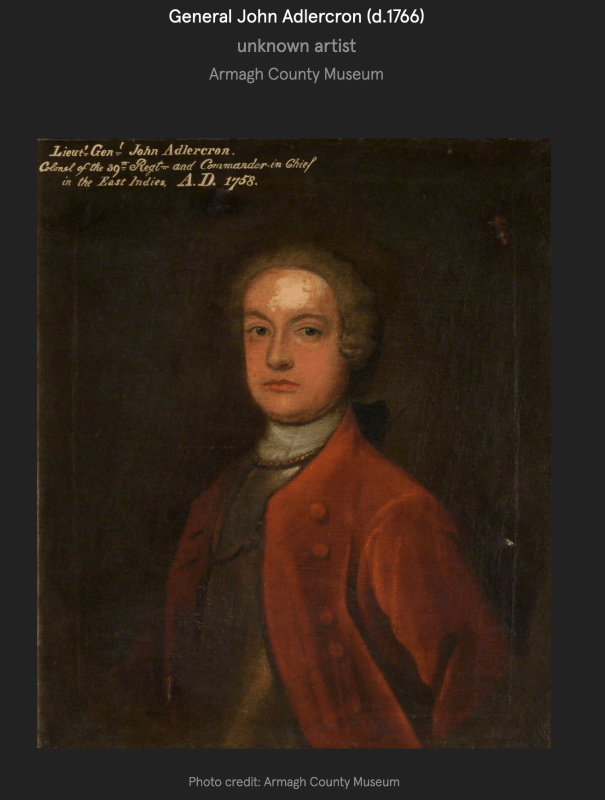

William’s son Henry (1663-1731) also sat in the Irish House of Parliament, representing Ardee and later, County Louth. He also served as Mayor of Drogheda. He was High Sheriff of County Louth and of County Armagh in 1708. He was raised to the Irish peerage as Baron Ferrard of Beaulieu soon after the accession of George I, for promoting the cause of William III in Ireland. He was also Governor of Drogheda. It was probably Henry Baron Ferrard who started work creating the house as we see it today. It was originally thought that the house was begun in William Tichbourne’s time, but due to a letter found by Dr. Edward McPartland in the Molesworth papers in the National Library of Ireland between the then Lord Molesworth and the 1st Lord Ferrard of Beaulieu, it suggests that the building work was carried out between 1710-1720. [15]

The front hall is described in Sean O’Reilly’s Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life:

“In the entrance hall the magnificence impresses itself on the visitor through architectural effect – the grandeur of the way it rises through two storeys, with the upper levels glazed, most unusually, on inner and outer walls. The internal windows, like those outside with sashes postdating the original construction, allow light to pass between the corridor and hall… the hall is interesting especially for its suggestion of the mixture of traditional or medieval and new Renaissance lifestyles. It is backward looking in the conception of a hall as public living room, a function it continues to serve today as it takes up such a huge proportion of the building… Yet the hall also looks ahead to the Renaissance in its classical articulation and enforced symmetry, all symbolising the power of intellectual discipline.” [16]

The guide told us that the front hall was actually the courtyard originally, and the front door of the house was the middle door at the back of the hall. There are even windows on the upper level of the hall, which were originally the front windows of the house, and they are part of the corridors upstairs and overlook the hall – see pictures on the website. None of my reference sources however state that this is the case, and the front hall was certainly built in the time of Henry Tichborne, Lord Ferrard.

There are more wooden carvings over two other doors in the Hall. One shows the coat of arms of Ferrard of Beaulieu, who commissioned the three carvings, and the other features musical instruments. The hall was probably used as a place for musical recitals and performances. The lovely plasterwork and panelling is original.

The coats of arms include that of William Tichbourne impaling those of his wife, Judith Bysse. More coats of arms embellish the fireplace.

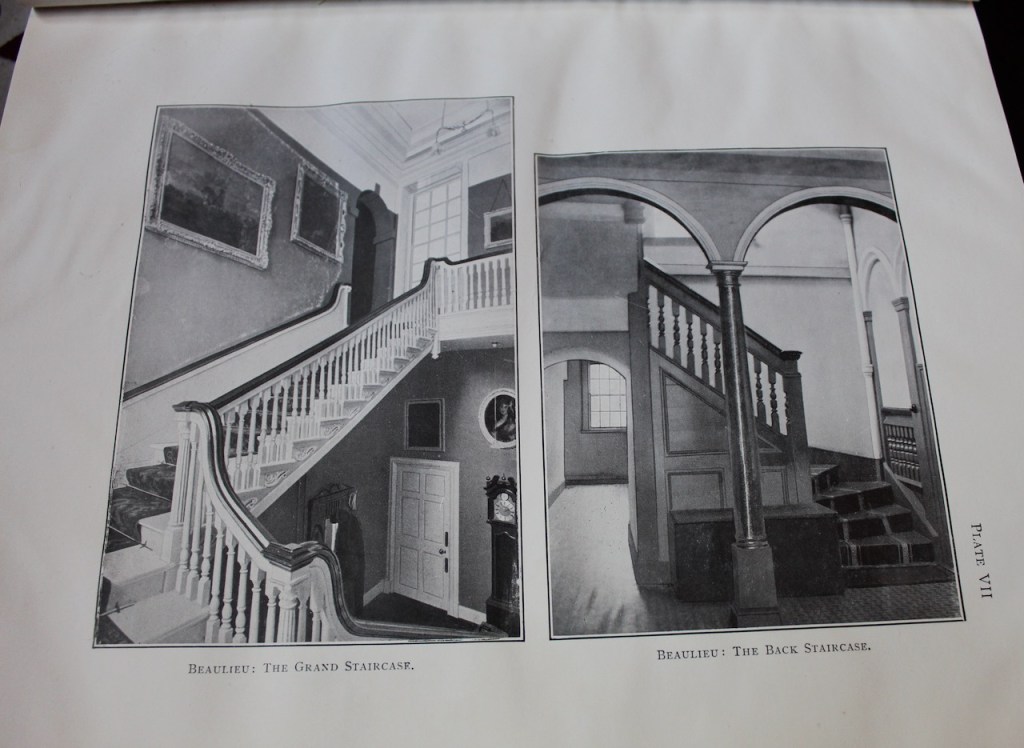

Henry Tichbourne Lord Ferrard wrote in a letter about his relief at finishing the current work on his house. He is proud of the staircase, which was probably delivered by boat, and assembled in Beaulieu, in 1723. The staircase has three flights, with carved balusters and the newels in the form of fluted Corinthian columns. As well as the staircase, it is said that the bricks were brought up the Boyne as ballast in boats, perhaps from Holland.

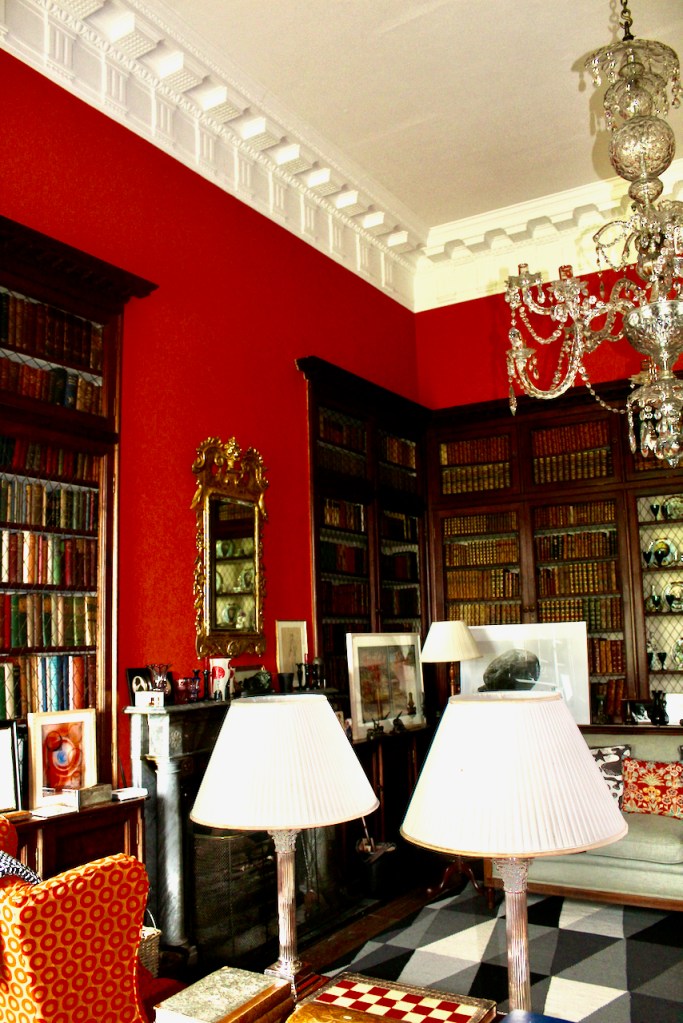

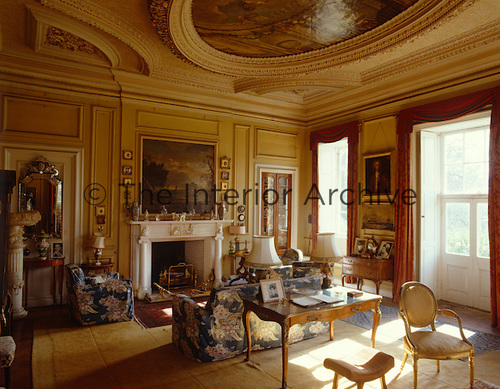

The wainscoted drawing room contains another work by Willem Van der Hagen, a magnificent trompe-l’oeil painting on the ceiling in a large plaster compartmental panel frame, with garlands of foliage and flowers. It pictures goddess Aurora descending in a chariot to her garden bower from the heavens [17].

Most of the other reception rooms also have wood panelling. A fine Italian marble fireplace adorns one of the reception rooms, with a classical carving of Neptune being drawn in a conch shell.

Van der Haagen also designed the gardens, including the terracing and the walled garden. [18] William Aston employed men to create two lakes on the property, in order to provide work in times of scarcity. There is a painting of him in the front hall, pointing toward the lakes.

Lord Ferrard’s sons predeceased him – the eldest was drowned when crossing to England in 1709. The estate therefore passed to Henry Tichbourne’s daughter, Salisbury Tichbourne, and her husband William Aston. [19]

I was fascinated to see the crest with the arm carrying a broken sword, on the chairs in the front hall. I thought it was the crest for the family in Clonalis. On further questioning, the guide told us that it refers to a joust undertaken by King Henry II of France. In 1559 King Henry II wanted to joust against the best jouster of his court. The courtier, Gabriel Montgomery, did not want to joust against King Henry for fear of winning, but Henry promised that no retribution would be taken. The jouster however killed Henry, breaking his jousting stick – which can be seen in the crest. The jouster fled, as despite the king’s assurances for his safety, the jouster could not trust that the king’s widow, Catherine de Medici, would not seek revenge! The broken lance forms part of the Montgomery crest.

Salisbury and William had a son, Tichborne Aston, who was an M.P. for Ardee. In 1746, he married Jane Rowan, daughter of William Rowan. They had a son and a daughter and the property passed down through the generations to its current owners. [20] After Tichborne died, Jane remarried, this time to Gawin Hamilton (1729-1805), of Killyleagh, County Down.

I loved that from upstairs you can look over the railing onto the front hall. We saw a bedroom which can be hired out for b&b, which sounds like a treat!

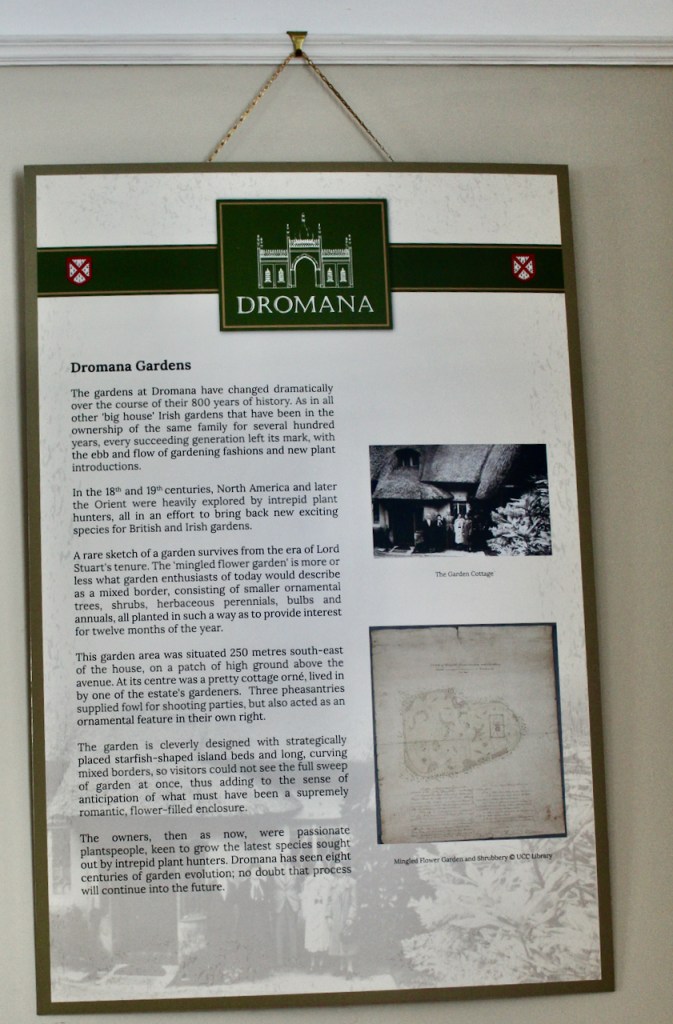

The Beaulieu website describes the gardens:

“Four acres of walled garden and grassy terraces surrounding Beaulieu have remained largely original to their early design. Lime trees form an avenue along the short, straight drive and picturesque lakes complete the vista at the front of the house. Family letters [those of Sir Henry, Baron Ferrard] describing the walled garden from this period, tell us that fruits such as figs and nectarines were being grown and also describe crops of flax, hops and bear.”

At the entrance to the walled garden is a lovely building with classic pillared portico that has been recently renovated:

Inside the attached garden shed is a fern-decked well:

The walled garden is absolutely splendid:

A chapel on the grounds is St. Brigid’s of Beaulieu. According to our guide, it was originally built in 1413 by William Plunkett, a pre-Reformation bishop, and his crypt is inside. Sadlier and Dickinson’s Georgian Mansions of Ireland in fact tells us that John Plunkett of “Bewly” and his wife Alicia founded a church within their manor as far back as the close of the thirteenth century, in the reign of Edward II! The latest version was built in 1807. It contains also a “cadaver stone” the guide told us, which was found in the mud flats of the river, which has a carved skeleton on it. According to Casey and Rowan, it is one of the earliest representations of cadaver figures in Irish medieval sculpture. It displays a female in an advanced state of decomposition, with a lurid range of reptilian life. Worms, toads, newts and lizards slide in and around the shroud. [21]

But instead of with death I leave you with life, of growth in the wonderful polytunnel.

[1] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/01/12/i-am-gabriel/

[2] p. 154-155. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan, The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster. The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, London, 1993.

[3] Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses.(originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[5] https://lvbmag.wordpress.com/2013/08/08/beaulieu-house-louth-gabriel-konig/

[6] p. 17-20. Sadlier, Thomas U. and Page L. Dickinson, Georgian Mansions in Ireland. Printed for the authors at the Dublin University Press, by Ponsonby and Gibbs, 1915.

[7] http://www.nli.ie/pdfs/mss%20lists/louth.pdf

“Though the Plunketts were deeply involved in the upheavals of the 1640s and 1689- 91, they survived with their lands intact. During the rebellion of 1641, the 6th Baron Louth, Oliver Plunkett, together with several other Catholic Old English lords of the Pale, formed an alliance with Irish rebel leaders from Ulster. The Catholic gentry of Louth appointed Lord Louth as colonel-general of the royalist forces to be raised in the county, though he declined the position. He was taken prisoner in 1642 and outlawed for high treason. Under the Cromwellian land settlement, his lands were forfeited. When Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, most of these lands were restored to Lord Louth and to his son Matthew.”

Also this site tells us of the earlier Plunketts at Beaulieu:

“The Plunkett family of Tallanstown, county Louth was descended from Sir Hugh de Plunkett, an Anglo-Norman who came to Ireland during the reign of Henry II. From then on the family owned lands in Louth. From the fourteenth century they lived at Bewley (Beaulieu) near Drogheda, and a branch of the family was associated with Tallanstown by the late fifteenth century. Early in the fourteenth century, John Plunkett of Bewley, a direct descendent of Sir Hugh, had two sons. One of these, Richard Plunkett, was the ancestor of two titled landowning families; the Earls of Fingall and the Barons of Dunsany, of Dunsany Castle, county Meath – Christopher Plunkett was created Lord Dunsany in 1461. The other son, John Plunkett of Bewley, was the ancestor of the Lords Louth. Of John Plunkett’s direct descendants, his grandson, Walter Plunkett of Bewley, was Sheriff of county Louth in 1401, a position later held by Sir John Plunkett of Bewley, Kilsaran and Tallanstown, who died in 1508. “

[8] https://beaulieuhouse.ie/a-short-history-of-beaulieu/ and also see the article in Country Life, October 28, 2015. https://beaulieuhouse.ie/cms/wp-content/uploads/Country-Life-OCT-28-BEAULIEU.pdf

[9] Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses.(originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Henry_Tichborne

[11] see Sadlier, Thomas U. and Page L. Dickinson, Georgian Mansions in Ireland. Printed for the authors at the Dublin University Press, by Ponsonby and Gibbs, 1915. See also Great Irish Houses, edited by Amanda Cochrane, published by Image Publications, London, 2008. The text of this book is by many authors, and individual entries are not credited. Text is by Desmond Fitzgerald, Desmond Guinness, Kevin Kelly, Amanda Cochrane, Ben Webb, William Laffan, Deirdre Conroy, Kate O’Dowd, Elizabeth Mayes and Richard Power.

[12] The best piece I have read about the Catholic Confederacy of the 1640s is by Micheál Siochrú, Confederate Ireland 1642–1649 A constitutional and political analysis. Four Courts Press, 1998.

[13] p. 81. Montgomery Massingberd, Hugh and Christopher Simon Sykes. Great Houses of Ireland. Laurence King Publishing, London, 1999.

[14] p. 17-20. Sadlier, Thomas U. and Page L. Dickinson, Georgian Mansions in Ireland. Printed for the authors at the Dublin University Press, by Ponsonby and Gibbs, 1915.

[15] p. 85. Montgomery Massingberd, Hugh and Christopher Simon Sykes. Great Houses of Ireland. Laurence King Publishing, London, 1999.

[16] p. 130. O’Reilly, Sean. Irish Houses and Gardens. From the Archives of Country Life. Aurum Press Ltd, London, 1998.

[17] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/06/29/a-room-with-a-view/

[18] p. 86. Great Irish Houses. Forewards by Desmond FitgGerald, Desmond Guinness. IMAGE Publications, 2008.

[19] p. 17-20. Sadlier, Thomas U. and Page L. Dickinson, Georgian Mansions in Ireland. Printed for the authors at the Dublin University Press, by Ponsonby and Gibbs, 1915. According to The Peerage website, Salisbury was the granddaughter of Henry Tichbourne: her father Robert Charles Tichbourne was the son of Lord Ferrard but he predeceased his father so the property passed to his son-in-law William Aston who had married Salisbury Tichbourne. This genealogy makes sense as it accounts for Salisbury’s unusual name, as Robert Charles Tichbourne married Hester Salisbury.

[20] Henry Tichborne, married Jane, daughter of Sir Robert Newcomen of Kenagh, County Longford. They had five sons and three daughters: Sir William Tichborne, the second but eldest surviving son, married Judith Bysse, daughter of John Bysse, Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer, by whom he was the father of Henry, first and last Baron Ferrard. Henry Baron Ferrard married Arabella Cotton. She was the daughter of Sir Robert Cotton, 1st Baronet of Combermere, in Cheshire. They had four sons (William, Cotton, Robert & Henry), all of whom died before their father leaving no male issue, so that at his death in 1731 his titles became extinct.

The son Robert Charles married Hester Salisbury and their only surviving daughter, Salisbury Tichborne, married William Aston, MP for Dunleer. They had a son, Tichborne Aston (1716-1748), who was an M.P. for Ardee. In 1746, he married Jane Rowan, daughter of William Rowan. Tichborne and Jane Aston had a son, William (1747-1769), and a daughter, Sophia.

According to Great Mansions of Ireland, while William Aston owned Beaulieu, the house had Lord Chief Justice Singleton as a tenant. This Chief Justice was a friend of the Lord Lieutenant, the four Earl of Chesterfield, which may explain why it is sometimes said that Lord Chesterfield himself occupied Beaulieu. In D’Alton’s History of Drogheda, a poet and bricklayer, Henry Jones, is said to have been born in Beaulieu. He was also a friend of the Earl of Chesterfield, and of Aston.

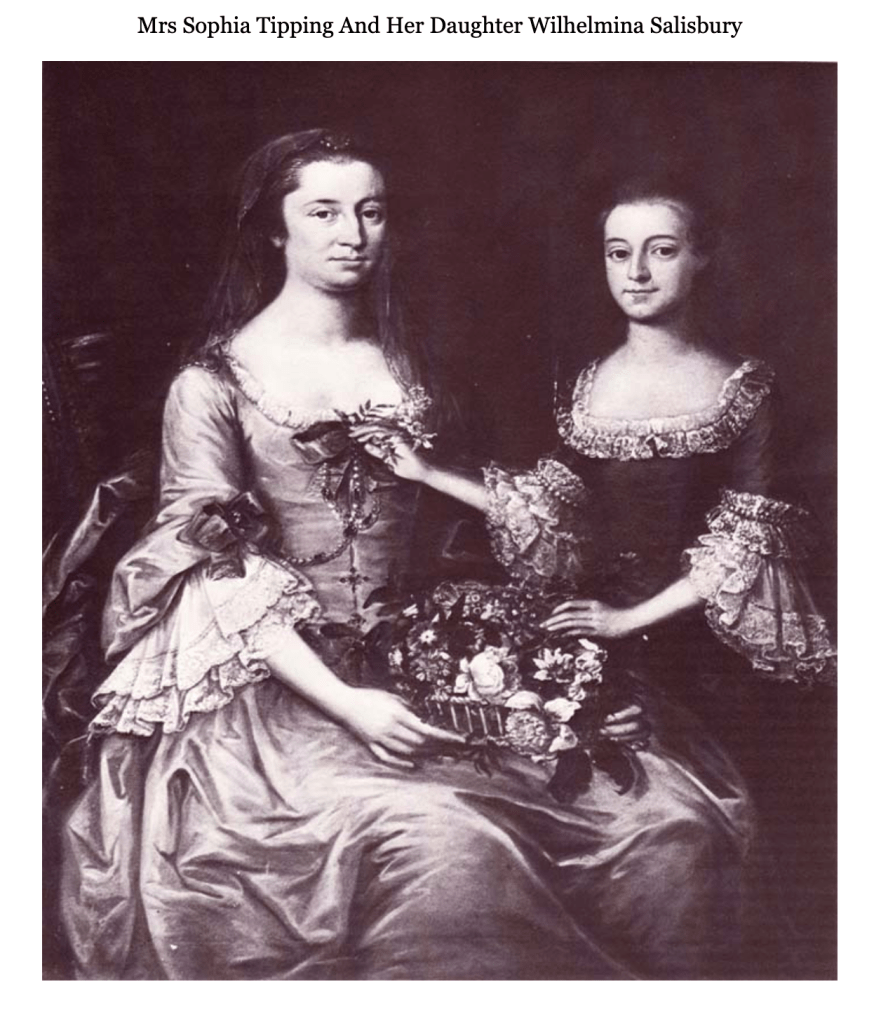

Sophia Aston married Thomas Tipping of Bellurgan, County Louth, who was M.P. for the borough of Kilbeggan. Her brother William died and Beaulieu passed to her. Their daughter Sophia-Mabella Tipping, married Rev Robert Montgomery, Rector of Monaghan, and the house passed to them. Another daughter, Elizabeth Tipping (d. 1775), married Lt.-Gen. Cadwallader Blayney, 9th Lord Blayney, Baron of Monaghan.

Rev Robert Montgomery and Sophia-Mabella had sons Rev. Alexander and (Captain)Thomas Montgomery.

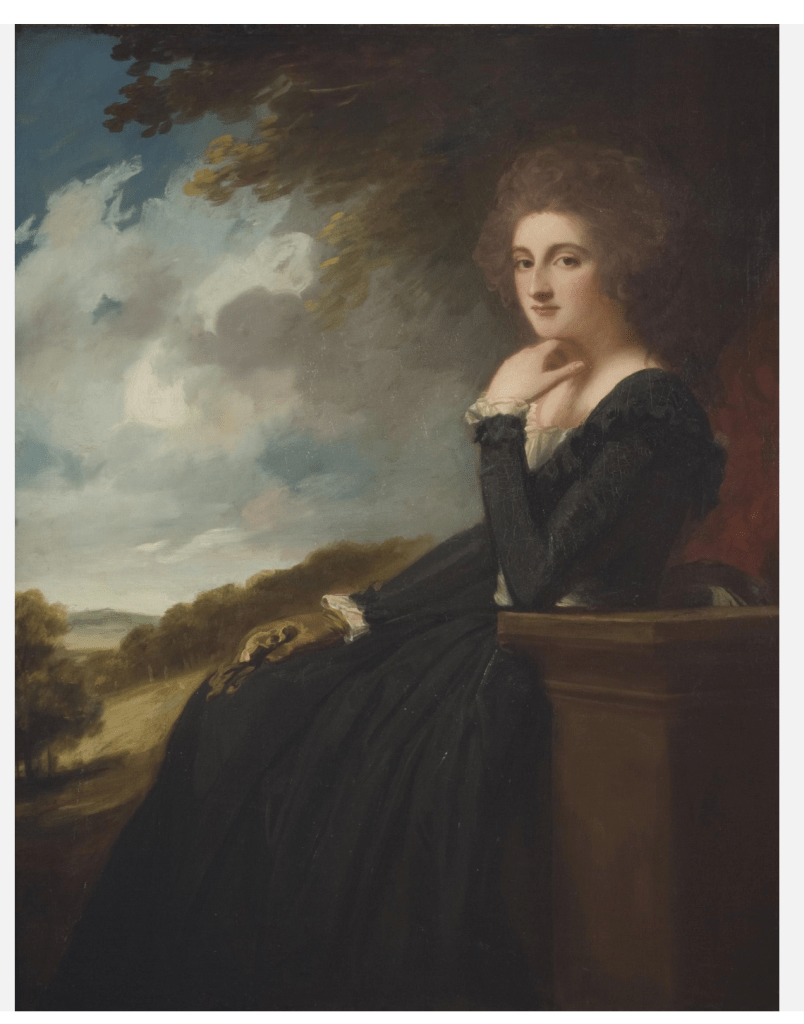

Reverend Alexander Montgomery married Margaret Johnson, and they had a son Richard Thomas Montgomery (1813-1890). According to his grave, Alexander Montgomery took on his wife’s name and became Alexander Johnson. The son, Richard Thomas, married Frances Barbara Smith.

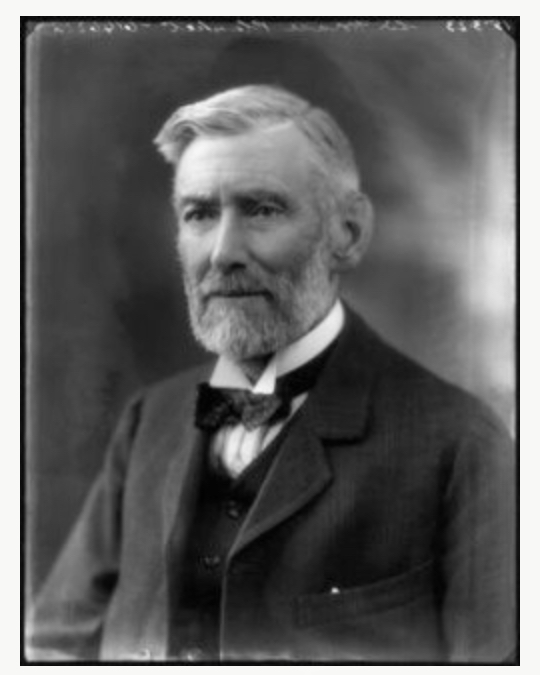

Their son Richard Johnson Montgomery (1855-1939) Maud Helenda Collingwood Robinson of Rokeby Hall.

Richard Johnston Montgomery’s daughter Sidney married Nesbit Waddington. They were parents of Gabriel and Penderell.

Gabriel Waddington married, and was mother of Cara, the current owner.

[21] p. 156. Casey, Christine and Alistair Rowan, The Buildings of Ireland: North Leinster. The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath. Penguin Books, London, 1993. You can see a picture of the stone at http://irishheraldry.blogspot.com/2014/09/heraldry-and-inscriptions-at-st-brigids.html

© Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com