www.borrishouse.com

Open dates in 2026: Open: Apr 1, 2, 7-12, 14-26, 28-30, May 5-10, 19-24, June 12-14, 16-18, 23-25, 30, Aug 5, 12-23, 25, 26, Sept 1, 2, 8, 9, 22, 23, 29 12pm-4pm

Fee: adult €12, OAP/student €10, child under 12 free

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

I had been particularly looking forward to visiting Borris House. It feels like I have a personal link to it, because my great great grandmother’s name is Harriet Cavanagh, from Carlow, and Borris House is the home of the family of Kavanaghs of Carlow, and the most famous resident of the house, Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh, was the son of a Harriet Kavanagh! Unfortunately I don’t think there’s a connection.

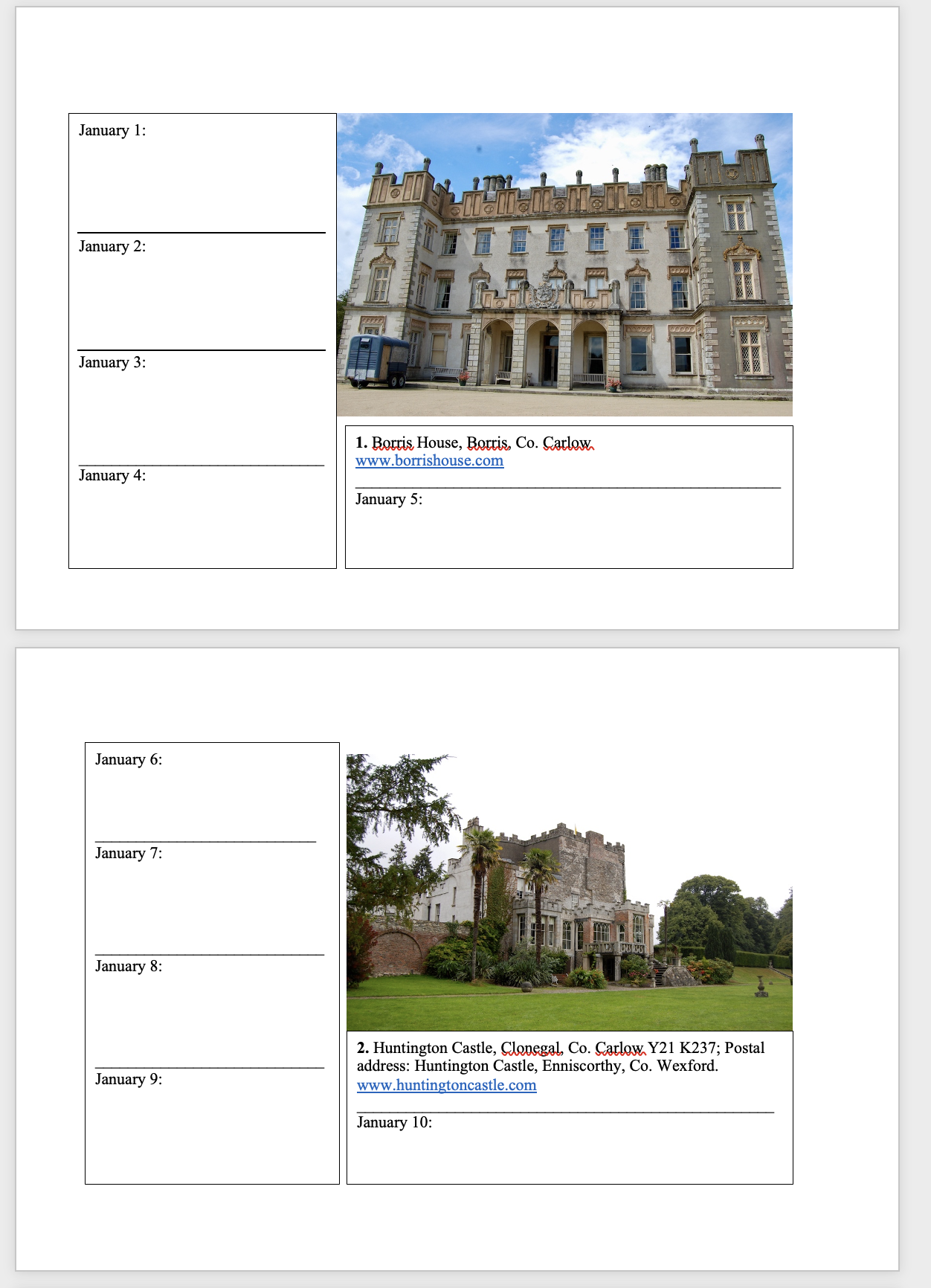

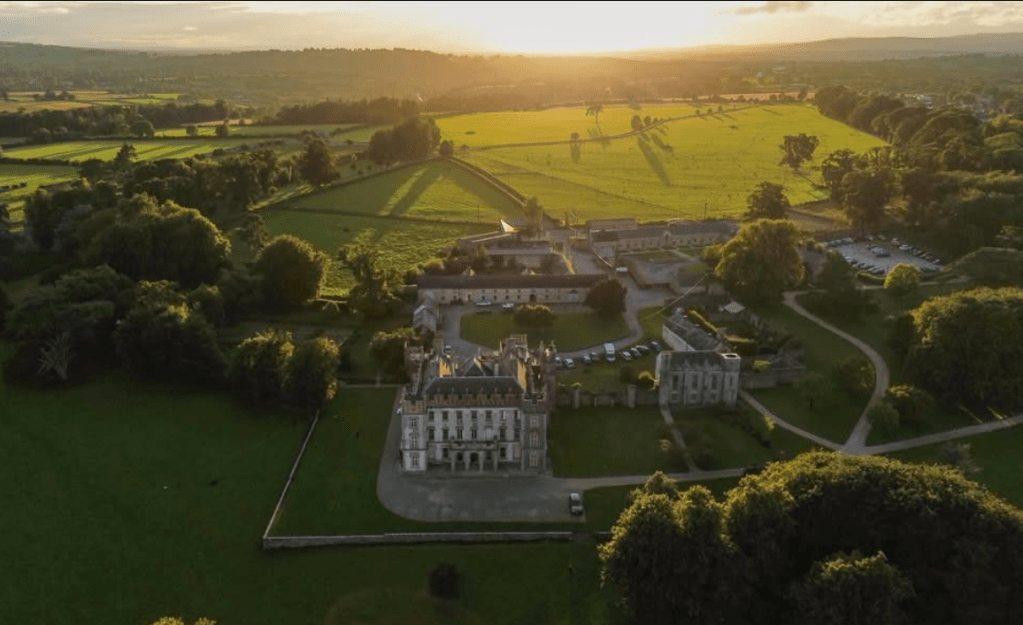

We were able to park right outside on the main street of Borris, across from the entrance. My fond familial feelings immediately faded when faced with the grandeur of the entrance to Borris House. I shrank into a awestruck tourist and meekly followed instructions at the Gate Lodge to make my way across the sweep of grass to the front entrance of the huge castle of a house.

Unlike other section 482 houses – with the few exceptions such as Birr Castle and Tullynally – Borris House has a very professional set-up to welcome visitors as one goes through the gate lodge. The website does not convey this, as it emphasises the house’s potential as a wedding venue, but the property is in fact fully set up for daily guided tours, and has a small gift shop in the gate lodge, through which one enters to the demesne. Borris House is still a family home and is inhabited by descendants of the original owners.

Originally a castle would have been located here on the River Barrow to guard the area. From the house one can see Mount Leinster and the Blackstairs Mountains.

The current owner Morgan Kavanagh can trace his ancestry back to the notorious Dermot MacMurrough (Diarmait mac Murchadha in Irish), who “invited the British in to Ireland” or rather, asked for help in protecting his Kingship. The MacMurroughs, or Murchadhas, were Celtic kings of Leinster. “MacMurrough” was the title of an elected Lord. Dermot pledged an oath of allegiance to King Henry II of Britain. The Norman “Strongbow,” or Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, came to Ireland to fight alongside Dermot MacMurrough against Dermot’s enemies. As a reward, Dermot MacMurrough offered Strongbow the hand of his daughter Aoife. This was less a love match than a chance to become the next King of Leinster. Succeeding generations of MacMurrough family controlled the area, maintaining their Gaelic traditions.

Timothy William Ferres tells us that in 1171, the name Kavanagh was given to Donell, son of Dermot MacMorrough. [1*]

In the late 14th century, Art mac Murchadha (d. around 1417) was one of the Irish kings who was offered a knighthood by King Richard II of England. In the 1500s, King Henry VIII sought to reduce the power of the Irish kings and to have them swear loyalty to him. In 1550 Charles MacMurrough Kavanagh (the Anglicised version of the name ‘Cahir MacArt’ MacMurrough Kavanagh) “submitted himself, and publicly renounced the title and dignity of MacMorrough, as borne by his ancestors.” [2] (note the various spellings of MacMorrough/MacMurrough). The head of the family was still however referred to as “the MacMorrough.”

We gathered with a few others to wait outside the front of the house for our tour guide on a gloriously sunny day in July 2019. Some of the others seemed to be staying at the house. For weddings there is accommodation in the house and also five Victorian cottages. We did not get to see these in the tour but you can see them on the website. Unfortunately our tour guide was not a member of the family but she was knowledgeable about the house and its history.

The current house was built originally as a three storey square house in 1731, incorporating part of a fifteenth century castle. We can gather that this was the date of completion of the house from a carved date stone.

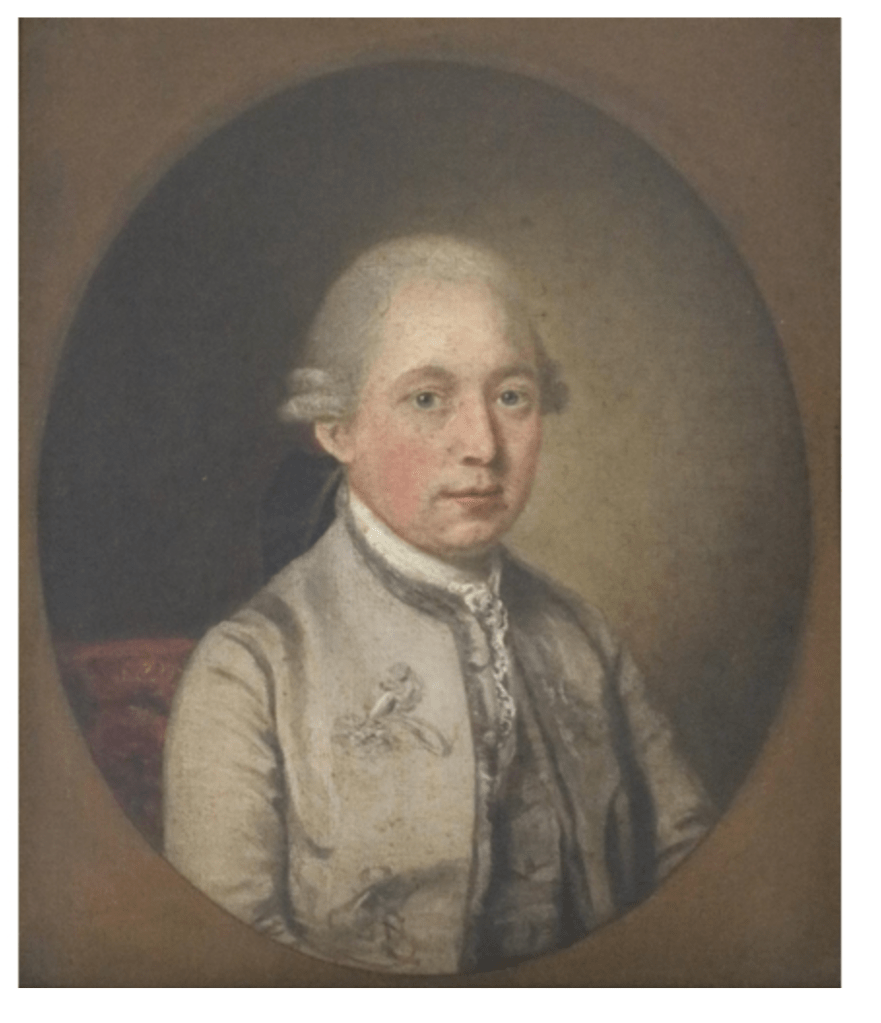

According to the Borris House website, the 1731 house was built for Morgan Kavanagh, a descendant of Charles MacMurrough Kavanagh. However, I have the date of 1720 as the death for Morgan Kavanagh. Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne writes that the 1731 house was built by Brian Kavanagh. [3] Morgan Kavanagh has a son named Brian (d. 1741), so it could be the case that the house was commissioned by Morgan and completed by his son.

The house was damaged in the 1798 Rebellion and rebuilt and altered by Richard and William Vitruvius Morrison around 1813 into what one sees today. According to Edmund Joyce in his book Borris House, Co. Carlow, and elite regency patronage, it was Walter Kavanagh, grandson of the aforementioned Brian (d. 1741) who commissioned the work, which was taken over by brother Thomas (1767-1837) when Walter died in 1818. [4]. The Morrisons gave it a Tudor exterior although as Mark Bence-Jones points out in his Guide to Irish Country Houses, the interiors by the Morrisons are mostly Classical.

The Morrisons kept the original square three storey building symmetrical. Edmund Joyce references McCullough, Irish Building Traditions, writing that “The Anglo-Irish landlords at the beginning of the 19th century who wanted to establish a strong family history with positive Irish associations were beginning to use the castle form – which had long been a status of power both in Ireland and further afield – to embed the notion of a long and powerful lineage into the mindset of the audience.”

In keeping with this castle ideal, the Morrisons added battlemented parapets with finials, the crenellated arcaded porch on the entrance, as well as four square corner turrets to the house, topped with cupolas (which are no longer there). The porch has slightly pointed arches, and is unusual with its bricklike rustication, and elongated mini towers on top with tawny detailing in between, reflected in the roof parapet.

They also created rather fantastical Tudor Gothic curvilinear hood mouldings over the windows, some “ogee” shaped (convex and concave curves; found in Gothic and Gothic-Revival architecture) [5].

These mouldings drop down from the top of the windows to finish with sculptured of heads of kings and queens. These are not representations of anyone in particular, the guide told us, but are idealised sculptures representing royalty to remind one of the Celtic kingship of the Kavanaghs.

As well as illustrating their heritage in architecture, Walter Kavanagh (d. 1718) commissioned an illustrated book of the family pedigree, titled “The pedigree of the ancient illustrious noble and princely house of Kavanagh in ancient times monarchs of Ireland and at the period of the invasion by Henry the second, kings of Leinster,” which traces the family tree back to 1670 BC! The connections to the prominent families of Butlers, Fitzjohns, De Mariscos and FitzGeralds are highlighted, which are also illustrated in the stained glass window in the main stairwell at Borris.

The guide pointed to the many configurations of windows on the front facade of the house. They were made different deliberately, she told us, to create the illusion that the different types of windows are from different periods, even though they are not! This was to reflect the fact that various parts of the building were built at different times.

The crest of the family on the front of the house on the portico features a crescent moon for peace, sheaf of wheat for plenty and a lion passant for royalty. The motto is written in Irish, to show the Celtic heredity of the Kavanaghs, and means “peace and plenty.”

The Morrisons also added a castellated office wing, joining the house to a chapel. This wing has been partially demolished.

Charles MacMurrough Kavanagh married Cecilia, daughter of Gerald Fitzgerald, 9th Earl of Kildare. Charles’s son Brian (c. 1526-1576) converted to Protestantism and sent his children to be educated in England. One of them, Sir Morgan Kavanagh, acquired the estate of Borris when he was granted the forfeited estates of the O’Ryans of Idrone in County Carlow.

When Protestants were attacked in 1641 by a Catholic rebellion, when Morgan’s son Brian (1595-1662) was “The MacMorrough,” the MacMurrough Kavanaghs were spared due to their ancient Irish lineage. Later, when Cromwell rampaged through Ireland, they were spared since they were Protestant, so they had the best of both worlds during those turbulent times.

Brian Kavanagh (1595-1662) married twice. His first wife was Elinor, daughter of Thomas Colclough of Tintern Abbey in County Wexford. His second wife was Elinor Blancheville of Blanchevillestown in County Kilkenny.

The tour guide took us first towards the chapel. She explained the structure of the house as we trooped across the lawn. She pointed out the partially demolished stretch between the square part of the house and the chapel. All that remains of this demolished section is a wall. The octagonal towerlike structures built into the wall were chimneys and the demolished part was the kitchen.

The square tower that joins the house to the demolished kitchen contained the nursery. The wing was demolished to reduce the amount of rates to be paid. The house was reoriented during rebuilding, the guide told us, and a walled garden was built with a gap between the walls which could be filled with coal and heated! I love learning of novel mechanisms in homes and gardens, techniques which are no longer used but which may be useful to resurrect as we try to develop more sustainable ways of living (not that we’d want to go back to using coal).

It is worth outlining some of the genealogy of this ancient family, as they intermarried with many prominent families of their day. Morgan Kavanagh (1668-1720) who probably commissioned the building of the 1730s house married Frances Esmonde, daughter of Laurence Esmonde (1634-1688) 2nd Baronet of Ballynastragh, County Wexford, who lived at Huntington Castle (another section 482 property I visited). After her death, he married Margaret Morres of Castle Morres in County Kilkenny.

Morgan and Frances née Esmonde’s son Brian (1699-1741) married Mary Butler, daughter of Thomas Butler (d. 1738) of Kilcash. Their son Thomas (1727-1790) married another Butler, Susanna, daughter of the 16th Earl of Ormonde.

It was the following generation, another Thomas (1767-1837), who is relevant to our visit to the chapel.

This Thomas (1767-1837) was originally a Catholic. He married yet another Butler, Elizabeth, daughter of the 17th Earl of Ormonde, in 1799. At some time he converted to Protestantism. It must have been before 1798 because in that year he represented Kilkenny City in Parliament and at that time only members of the Established Church could serve in Parliament.

As I mentioned, the house was badly damaged in 1798, when the United Irishmen rose up in an attempt to create an independent Ireland. Although the Kavanaghs are of Irish descent and are not a Norman or English family, this did not save them from the 1798 raids. The house was not badly damaged in a siege but outbuildings were. The invaders were looking for weapons inside the house, the guide told us. Robert O’Byrne the Irish Aesthete writes tells us: “Walter MacMurrough Kavanagh wrote to his brother-in-law that although a turf and coal house were set on fire and efforts made to bring ‘fire up to the front door under cover of a car on which were raised feather beds and mattresses’ [their efforts] were unsuccessful.” [6]

Edmund Joyce describes the raid in his book on Borris House (pg. 21-22):

“The rebels who had marched overnight from Vinegar Hill in Wexford…arrived at Borris House on the morning of 12 June. They were met by a strong opposing group of Donegal militia, who had taken up their quarters in the house. It seems that the MacMurrough Kavanaghs had expected such unrest and in anticipation had the lower windows…lately built up with strong masonry work. Despite the energetic battle, those defending the house appear to have been indefatigable, and the rebels, ‘whose cannons were too small to have any effect on the castle…’ the mob retreated back to their camps in Wexford.”

The estate was 30,000 acres at one point, but the Land Acts reduced it in the 1930s to 750 acres, which the present owner farms organically. The outbuildings which were built originally to house the workings of the house – abbatoir, blacksmith, dairy etc, were burnt in one of the sieges and so all the outbuildings now to be seen, the guide told us, were built in the nineteenth century.

Thomas’s second wife, Harriet Le Poer Trench, daughter of the 2nd Earl of Clancarty, was of staunch Scottish Protestant persuasion [7]. When he converted, the chapel had to be reconsecrated as a Protestant chapel. According to legend, Lady Harriet had a statue of the Virgin Mary removed from the chapel and asked the workmen to get rid of it. The workmen, staunch Catholics, buried the statue in the garden. People believed that for this act, Lady Harriet was cursed, and it was said that one day her family would be “led by a cripple.”

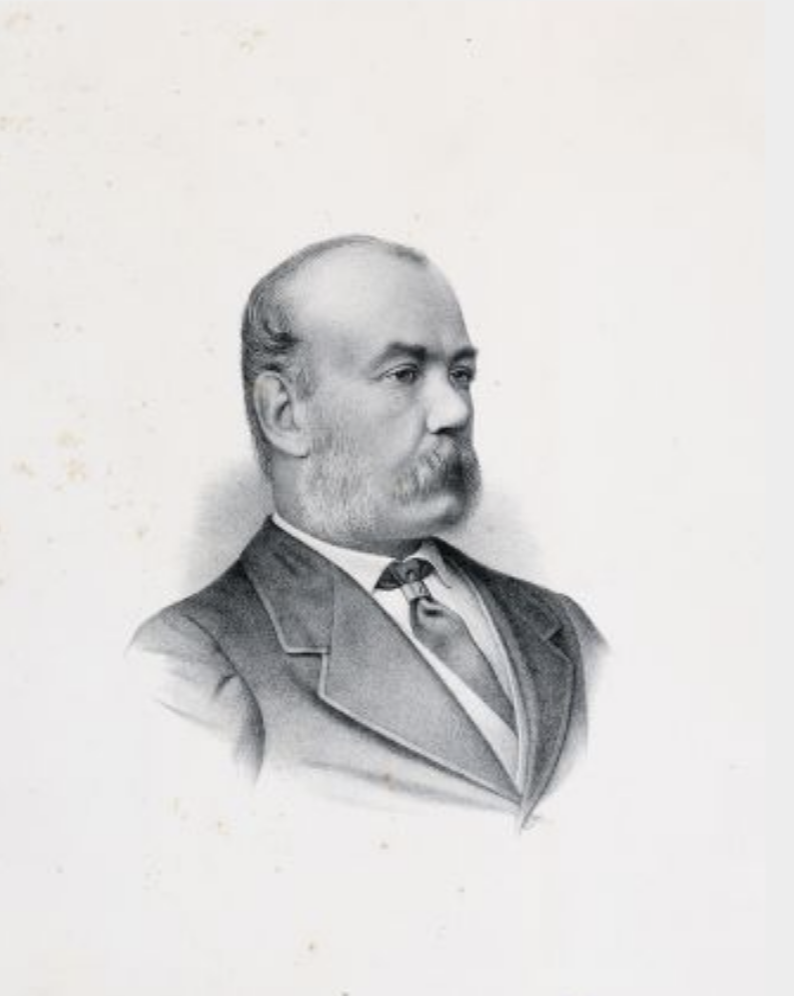

The story probably came about because Harriet’s third son, Arthur, was born without arms or legs. As she had given birth to two older sons, and he had another half-brother, Walter, son of Thomas’s first wife, it seemed unlikely that Arthur would be the heir. However, the three older brothers all died before Arthur and Arthur did indeed become the heir to Borris House.

The plasterwork in the chapel, which is called the Chapel of St. Molin, is by Michael Stapleton.

In Jimmy O’Toole’s book The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! (published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare), he tells us of a rather miraculous finding of a Bible giving evidence of Thomas’s early Catholicism:

p. 130. “In the early 1950s, Borris House needed an electrical rewire. It was the kind of job in this rambling mansion that would take tradesmen into all sorts of unused nooks and crannies, attics untouched since the last electricians were there, and of course, there was the necessary task, dreaded by owners, the lifting of floor boards…What the electricians turned up from underneath the floor boards in the library of borris House was an 18C missal, which had been carefully wrapped and placed there by the Catholic Thomas Kavanagh either when he conformed to the Established Church, or when he married for the second time in 1825. The missal was a gift from his mother, the former Lady Suzanna Butler, bearing the hopeful inscription that he would remain faithful to the Catholic religion practised for centuries by his forebears, who could trace their ancestry back to early Christian times.”

Jimmy O’Toole also tells us that Borris House stands on 9th century dungeons!

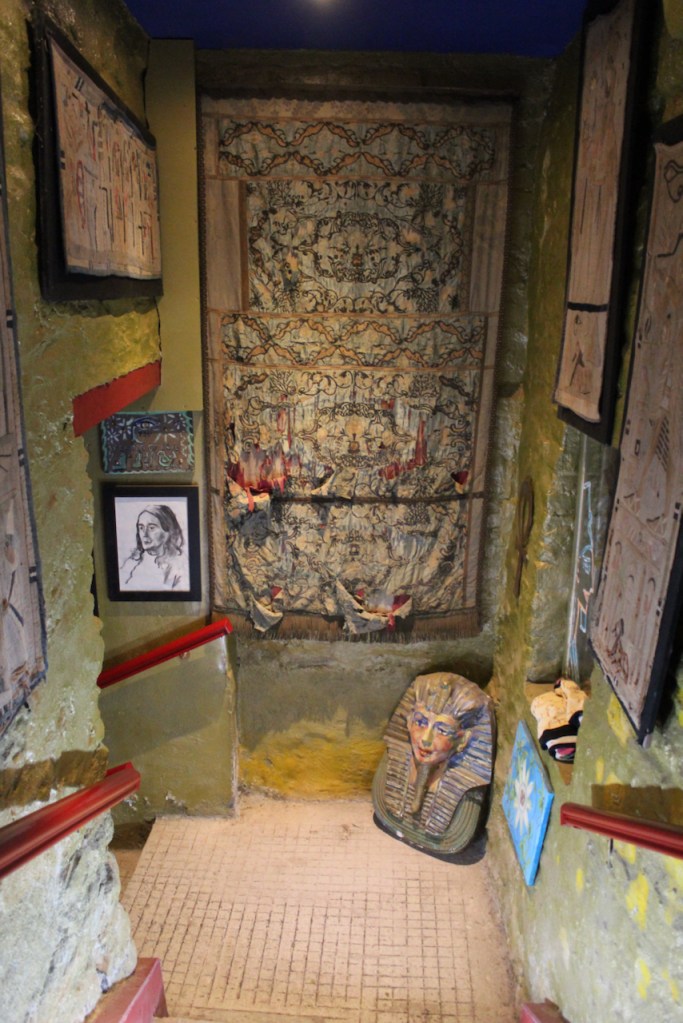

While we sat in the chapel, our guide told us about the amazing Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh. When her husband Walter died, Harriet and her children went travelling. They travelled broadly, and she painted, and collected objects which she brought back to Ireland, including a collection of artefacts from Egypt now in the National Museum of Ireland. When Arthur was 17 years old his mother sent him travelling again, to get him away from his high jinks with the local girls. Arthur kept diaries, which are available for perusal in the National Library. I must have a look! I have a special interest in diaries, since I have been keeping my own since I was twelve years old. Some of Arthur’s adventures include being captured and being cruelly put on display by a tribe. He also fell ill and found himself being nursed back to health in a harem – little did the Sultan or head of the harem realise that Arthur was perfectly capable of impregnating the ladies!

Arthur’s brother and tutor died on their travels and Arthur found himself alone in India. He joined the East India Company as a dispatch rider – he was an excellent horseman, as he could be strapped in to a special saddle, which we saw inside the house, now mounted on a children’s riding horse! I was also thrilled to see his wheelchair, in the Dining Room, which is now converted into a dining chair.

When Arthur came home as heir, he found his mother had set up a school of lacemaking, now called Borris Lace, to help the local women to earn money during the difficult Famine years. The lace became famous and was sold to Russian and English royalty. The rest of the estate, however, was in poor shape. Arthur set about making it profitable, bringing the railway to Borris, building a nearby viaduct, which cost €20,000 to build. He also built cottages in the town, winning a design medal from the Royal Dublin Society, and he set up a sawmill, from which tenants were given free timber to roof their houses. He set up limekilns for building material, and also experimented (unsuccessfully) with “water gas” to power the crane used to built the viaduct. His mother built a fever house, dower house and a Protestant school, and Arthur’s sisters built a Catholic school. There is a little schoolhouse (with bell) behind the chapel.

Arthur seems to have had a great sense of humour. On one of his visits to Abbeyleix, he remarked to Lady De Vesci, “It’s an extraordinary thing – I haven’t been here for five years but the stationmaster recognised me.”

Arthur married Mary Frances Forde-Leathley and fathered six children. He became an MP for Carlow and Kilkenny, and sat in the House of Commons in England, which he reached by sailing as far as London, where he was then carried in to the houses of Parliament.

He lost when he ran again for Parliament in 1880, beaten by the Home Rule candidates. He returned from London after his defeat and saw bonfires, which were often lit by his tenants to celebrate his return. However, this time, horrifically, he saw his effigy being burned on the bonfires by tenants celebrating the triumph of the Home Rule candidates. He must have been devastated, as he had worked so hard for his tenants and treated them generously. For more about him, see the Irish Aesthete’s entry about him. [8]

Jimmy O’Toole’s book gives a detailed description of politics at the time of Arthur’s defeat and explains why the tenants behaved in such a brutal way. Elections grew heated and dangerous in the days of the Land League and of Charles Stewart Parnell, when tenants hoped to own their own land. In the 1841 election, tenants of the Kavanaghs were forced to vote for the Tory candidate against Daniel O’Connell Jr., despite a visit from Daniel O’Connell Sr, “The Liberator” who fought for Catholic emancipation.

The land agent for the Kavanaghs, Charles Doyne, threatened the tenants with eviction if they did not vote for his favoured candidate. In response to threats of eviction, members of the Land League forced tenants to support their cause by publicly shaming anyone who dared to oppose them. People were locked into buildings to prevent them from voting, or on the other hand, were locked in to protect them from attacks which took place if they planned to support the Tory candidate. Not all Irish Catholics supported the Land League. Labourers realised that landlords provided employment which would be lost if the land was divided for small farmers.

It was Arthur’s grandfather, Thomas (b. 1727), who undertook much of the renovation work at Borris in the 1800s, with money brought into the family by his wife, Susanna Butler. [9] Under her influence, Italian workmen were employed and ceilings were decorated and Scagliola pillars installed. After hearing the stories about amazing Arthur, we returned across the lawn to enter the main house.

The front hall is square but is decorated with a circular ceiling of rich plasterwork, “treated as a rotunda with segmental pointed arches and scagliola columns; eagles in high relief in the spandrels of the arches and festoons above,” as Mark Bence-Jones describes in his inimitable style [see 5, p. 45]. We were not allowed to take photographs but the Irish Aesthete’s site has terrific photographs [see 3]. The eagles represent strength and power. There are also the sheafs of wheat, crescent moons and lion heads, symbols from the family crest. Another common motif in the house is a Grecian key pattern.

The craftwork and furnishings of the house are all built by Irish craftsmen, including mahogany doors. There is a clever vent in the wall that brings hot air from the kitchens to heat the room.

We next went into the music room which has a beautiful domed oval ceiling with intricate plasterwork. It includes the oak leaf for strength and longevity.

The drawing room has another pretty Stapleton ceiling, more feminine, as this was a Ladies’ room. It has lovely pale blue walls, and was originally the front entrance to the house. When it was made into a circular room the leftover bits of the original rectangular room form small triangular spaces, which were used as a room for preparing the tea, a small library with a bookcase, and a bathroom. The curved mahogany doors were also made by Irish craftsmen in Dublin, Mack, Williams and Gibton.

The dining room has more scagliola columns at one end, framing the serving sideboard, commissioned specially by Morrison for Borris House. It was sold in the 1950s but bought back by later owners. [10] The room has more rich plasterwork by Michael Stapleton: a Celtic design on the ceiling, and ox skulls represent the feasting of Chieftains. With the aid of portraits in the dining room, the guide told us more stories about the family. It was sad to hear how Arthur had to put an end to the tradition of the locals standing outside the dining room windows, and gentry inside, to observe the diners. He did not like to be seen eating, as he had to be fed.

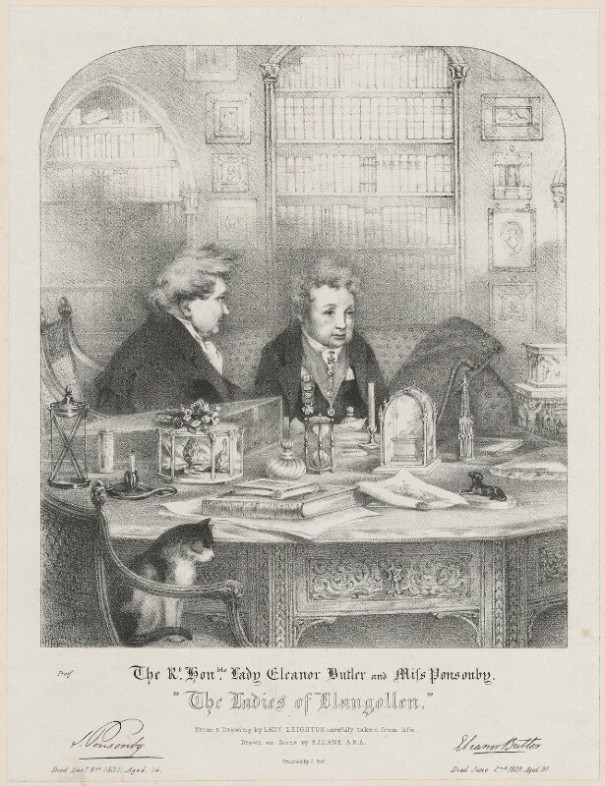

We saw the portrait of Lady Susanna’s husband, whom her sister Charlotte Eleanor dubbed “Fat Thomas.” Eleanor formed a relationship with Sarah Ponsonby, and they ran away from their families to be together. As a result, Eleanor was taken to stay with her sister’s family in Borris House, and she must have felt imprisoned by her sister’s husband, hence the insulting moniker. Eleanor managed to escape and to make her way to Woodstock, the house in County Kilkenny where Sarah was staying. Finally their families capitulated and accepted their plans to live together. They set up house in Wales, in Llangollen, and were known as The Ladies of Llangollen They were visited by many famous people, including Anna Seward, William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, Charles and Erasmus Darwin, Sir Arthur Wellesley and Josiah Wedgewood.

Mark Bence-Jones describes an upstairs library with ceiling of alternate barrel and rib vaults, above a frieze of wreaths that is a hallmark of the Morrisons, which unfortunately we did not get to see. We didn’t get to go upstairs but we saw the grand Bath stone cantilevered staircase. The room was originally an open courtyard.

We then went out to the Ballroom, which was originally built by Arthur as a billiard room, with a gun room at one end and a planned upper level of five bedrooms. The building was not finished as planned as Arthur died. It is now used for weddings and entertainment.

In 1958 the house faced ruin when Joane Kavanagh’s husband Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Macalpine-Downie died, and she decided to move to a smaller house. However, her son, Andrew Macalpine-Downie, returned to Borris after a career as a jockey in England. with his wife Tina Murray. He assumed the name Kavanagh, and set himself the task of preventing the house from becoming a ruin. [11]

We were welcomed to wander the garden afterwards.

[1*] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2013/07/borris-house.html

[2] p. 33, MacDonnell, Randal. The Lost Houses of Ireland. A chronicle of great houses and the families who lived in them. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. London, 2002.

[3] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/11/04/an-arthurian-legend/

The Borris website claims that the 1731 house was built for Morgan Kavanagh, but the Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne writes that the 1731 house was built by Brian Kavanagh, incorporating part of the fifteenth century castle. I have the date of 1720 as the death for Morgan Kavanagh and he has a son, Brian, so it could be the case that the house was commissioned by Morgan and completed by his son Brian.

[4] Joyce, Edmond. Borris House, Co. Carlow, and elite regency patronage. Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2013.

[5] https://irishhistorichouses.com/2020/04/18/architectural-definitions/

and Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses [originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978]; Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[6] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/11/04/an-arthurian-legend/

This entry also has lovely pictures of the inside of Borris House and more details about the history of the house and family.

[7] p. 130. O’Toole, Jimmy. The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! Published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare.

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/11/04/an-arthurian-legend/

[9] for more on the Butlers see John Kirwan’s book, The Chief Butlers of Ireland and the House of Ormond, An Illustrated Genealogical Guide, published by Irish Academic Press, Newbridge, County Kildare, 2018. Stephen and I went to see John Kirwan give a fascinating talk on his book at the Irish Georgian Society’s Assembly House in Dublin.

[10] p. 115. Fitzgerald, Desmond et al. Great Irish Houses. Published by IMAGE Publications Ltd, Dublin, 2008.

[11] p. 134. O’Toole, Jimmy. The Carlow Gentry: What will the neighbours say! Published by Jimmy O’Toole, Carlow, Ireland, 1993. Printed by Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Kildare.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com