Tourist Accommodation Facility – not open to the public

Open for accommodation in 2026: Apr 1 – Nov 15

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

When I saw that Roderick Perceval was giving a tour of his home, Temple House in County Sligo, during Heritage Week 2025, I jumped at the chance to see it and booked straight away. I had booked to stay there in the past but had to cancel, and before this tour, the only way to see this section 482 property was to stay, as it was listed as tourist accommodation. And before you get your hopes up, unfortunately it no longer is providing individual bed and breakfast (with dinner optional) accommodation, as Roderick and his family have decided to focus instead on larger group accommodation and weddings. The website now gives the option to book three or more double rooms for your stay. There is also a self-catering cottage available, which has 4 bedrooms: 1 King, 1 Double, 2 Twin.

The Percevals have lived at this location since 1665. Before the current house was built, around 1820 according to Mark Bence-Jones, they lived in another property closer to Templehouse Lake, part of the Owenmore River. [1] The remnants of the earlier house sit adjacent to the ruins of a Knights Templar castle from around 1181, after which the property takes its name. [2]

We came across the medieval order of knights when we visited The Turret in County Limerick during Heritage Week in 2022, a house which was built on the foundations of a construction by the Knights Hospitaller, a different branch of religious warriors. The Knights Templar were a religious order established in the eleventh century to protect Jerusalem for Christianity, and were named after Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. Like other religious orders, the members took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

A book review by Peter Harbison of Soldiers of Christ: the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller in medieval Ireland edited by Martin Brown OSB and Colmán Ó Clabaigh OSB tells us that Templars came into Ireland under the protection of the English crown and acted on behalf of the king against the native Irish. Templar Knights helped govern Ireland and often gained high office. [3]

When Stephen and I stayed at nearby Annaghmore house with Durcan O’Hara, he told me that he is related to the Percevals of Temple House. An O’Hara, it is believed, may have joined the Knights Templar and donated the land near Temple House. [see 2]

The Templar castle passed to the Knights of St. John the Hospitallers when the Knights Templar were disbanded in the 1300s. In France, Templars were burnt at the stake and their land seized by the crown but in other countries their property was transferred to the Knights Hospitallers, known today as the Knights of Malta.

Robert O’Byrne tells us in his blog that the land formerly owned by the Knights Templar came into the hands of the O’Haras, and that they built a new castle here around 1360. He adds that in the 16th century the same lands, along with much more beside, were acquired by John Crofton, who had come here in 1565 with Sir Henry Sidney following the latter’s appointment as Lord Deputy of Ireland. [4]

Roderick told us that the Croftons acquired the property around 1609, and that Henry Crofton built a thatched Tudor house around 1627. The National Inventory tells us that the remains of the house near the Templar ruins are of a two-bay two-storey stone house, built c.1650. [5]

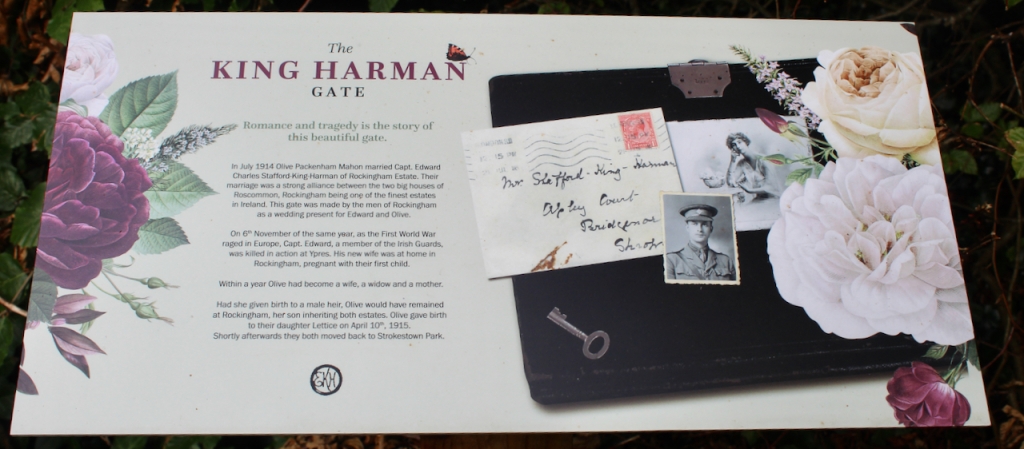

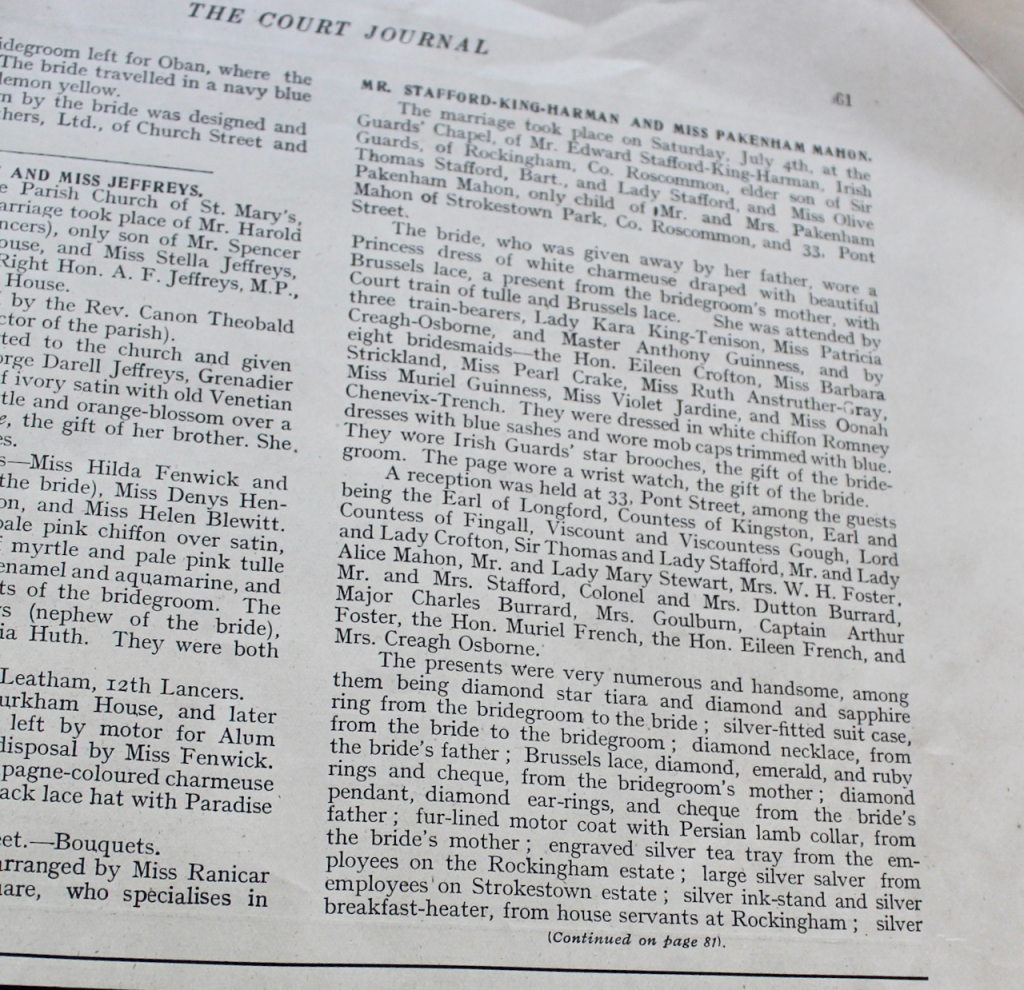

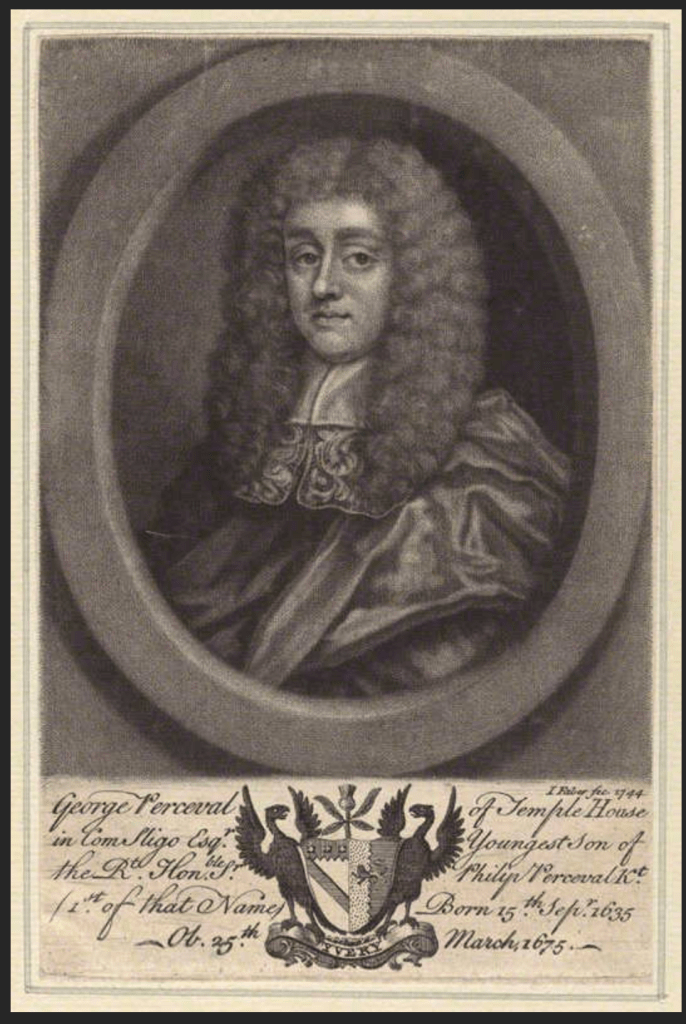

It came into the Perceval family in 1665 when George Perceval (1635-1675) married Mary Crofton.

We came across the Percevals when we visited Burton Park in County Cork, another section 482 property in 2025 (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2024/02/08/burton-park-churchtown-mallow-county-cork-p51-vn8h/ ).

George’s father Philip (1605-1647) came from England to Ireland to serve as registrar of the Irish court of wards, along with his brother Walter. This position would have given him an insight to property ownership in Ireland. When a son inherited property before he came of age, he was made a Ward of the state, and the someone would be chosen to act on the child’s behalf.

When Walter died in 1624, Philip inherited the family estates in England and Ireland. The land at Burton Park was named after his estate in Somerset, Burton.

Philip’s grandfather Richard Perceval was ‘confidential agent’ to Queen Elizabeth’s Minister Lord Burleigh. He had correctly identified Spanish preparations for the Armada and this vitally important information was rewarded with Irish estates. [6]

Philip settled in Ireland, and by means of his interest at court he gradually obtained a large number of additional offices. In 1625 he was made keeper of the records in the Birmingham Tower at Dublin Castle.

Perceval was close to the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford. With the fall and execution of Wentworth in May 1641, Perceval lost his major patron and protector. In September 1641 Perceval narrowly avoided prosecution in England when his part in a shady land transaction was revealed. By that time, Perceval owned over 100,000 acres in Ireland, which he obtained partly through forfeited lands.

Philip Perceval married Catherine Ussher, daughter of Arthur Ussher and Judith Newcomen. She gave birth to their heir, John (1629–1665), who was created 1st Baronet of Kanturk, County Cork in 1661. George (1635-1675) was the younger son. He held the position of Registrar of the Prerogative Court in Dublin.

George Perceval’s wife Mary’s father William Crofton was High Sheriff of County Sligo in 1613 and Member of Parliament for Donegal in 1634, so George and Mary might have met in Dublin. Mary, as heiress, was a good match, and since George was a younger son, marrying into property would have suited him well.

Robert O’Byrne tells us that they lived in the old castle which had been converted by the Croftons into a domestic residence in 1627. [see 4] It is not clear to me whether George and Mary lived in a house next to the Templar castle or in some version of the castle itself. O’Byrne tells us that the castle had been besieged and badly damaged in 1641, but was repaired. [see 4].

George died at the young age of forty when on a ship crossing to Holyhead, when his son and heir Philip (1670-1704) was only five years old. [7] Philip’s mother remarried, this time to Richard Aldworth, who was Chief Secretary of Ireland. Philip also died young, after marrying and having several children, and the property passed to his son John (1700-1754), who was also minor when his father died.

John (1700-1754) married the daughter of a neighbour, Anne Cooper of Markree Castle, another Section 482 property in 2025 (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2021/11/06/markree-castle-collooney-co-sligo/). Anne gave birth to their son and heir Philip (1723-87).

Philip Perceval (1723-87) married Mary Carlton of Rossfad, County Fermanagh. Their son and heir Guy died soon after his father so the property passed in 1792 to Guy’s brother Reverend Philip Perceval.

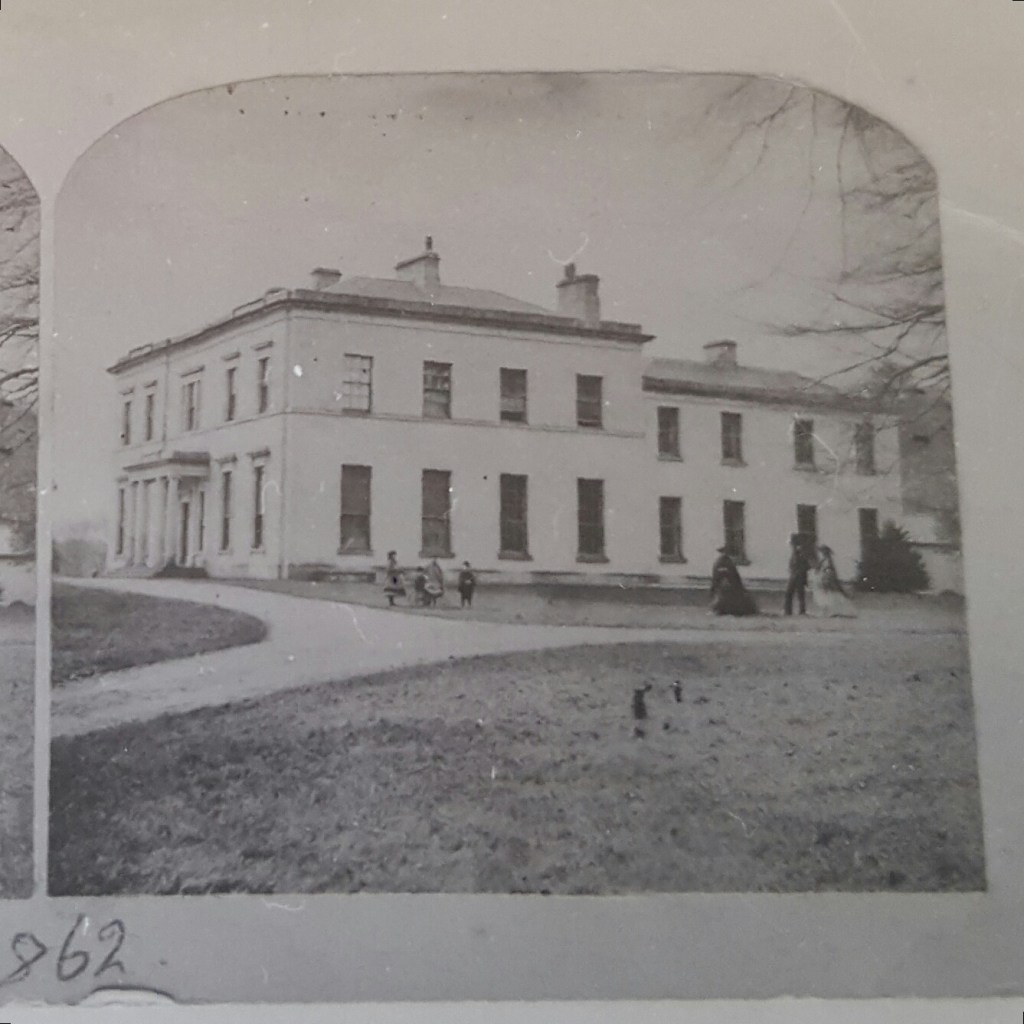

The house is featured in a chapter of Great Irish Houses by Desmond Fitzgerald the Knight of Glin and Desmond Guinness. They tell us that in 1825 Reverend Philip’s son Colonel Alexander Perceval (1787-1858) built a neo-classical two story house up the hill from the castle on the present site.

What is the now the side of the house was once the front.

The house at this time was of two storeys and had five bays on the front, with the centre bay slightly recessed, with an enclosed single storey Ionic porch, and a Wyatt window over the porch.

Before building the house, Alexander Perceval (1787-1858), in 1808, married Jane Anne, eldest daughter of Colonel Henry Peisley L’Estrange, of Moystown, King’s County.

After building the house, Alexander served as MP for Sligo between 1831 and 1841, and from 1841-1858 was sergeant-at-arms to the House of Lords in England.

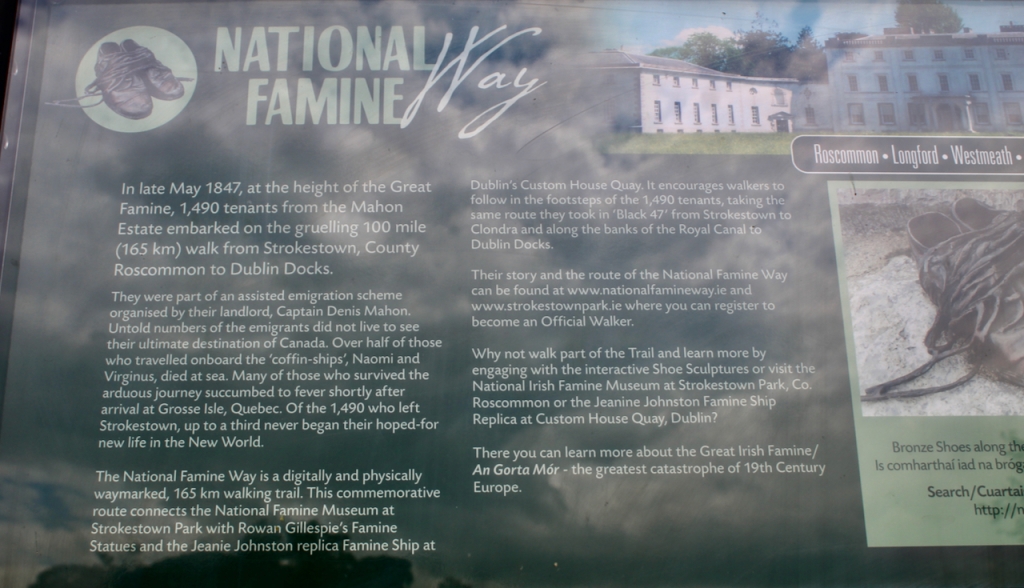

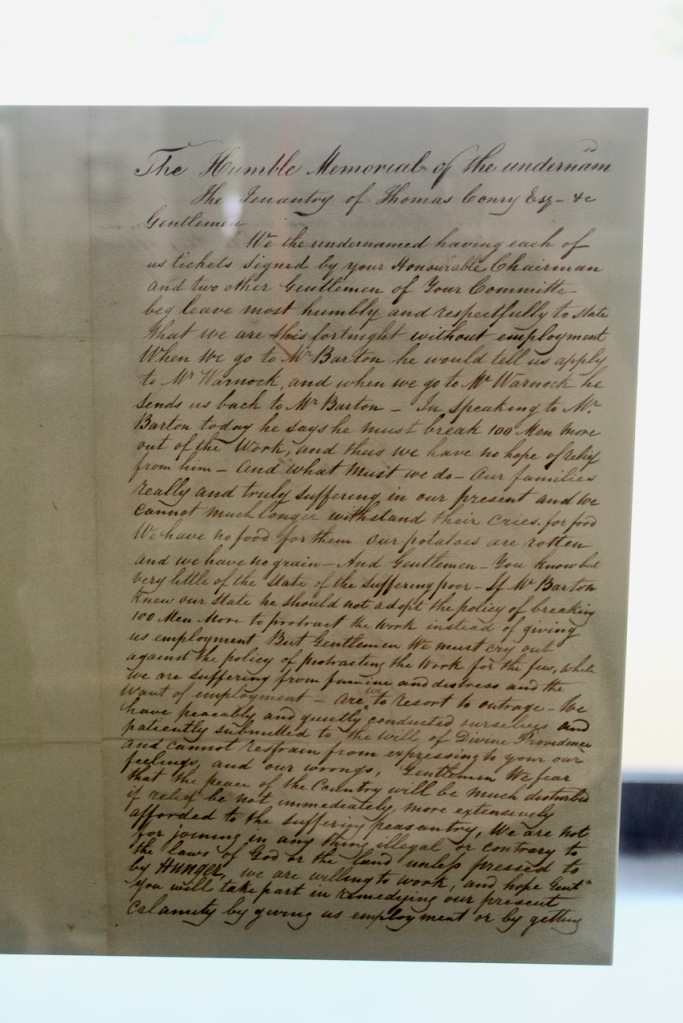

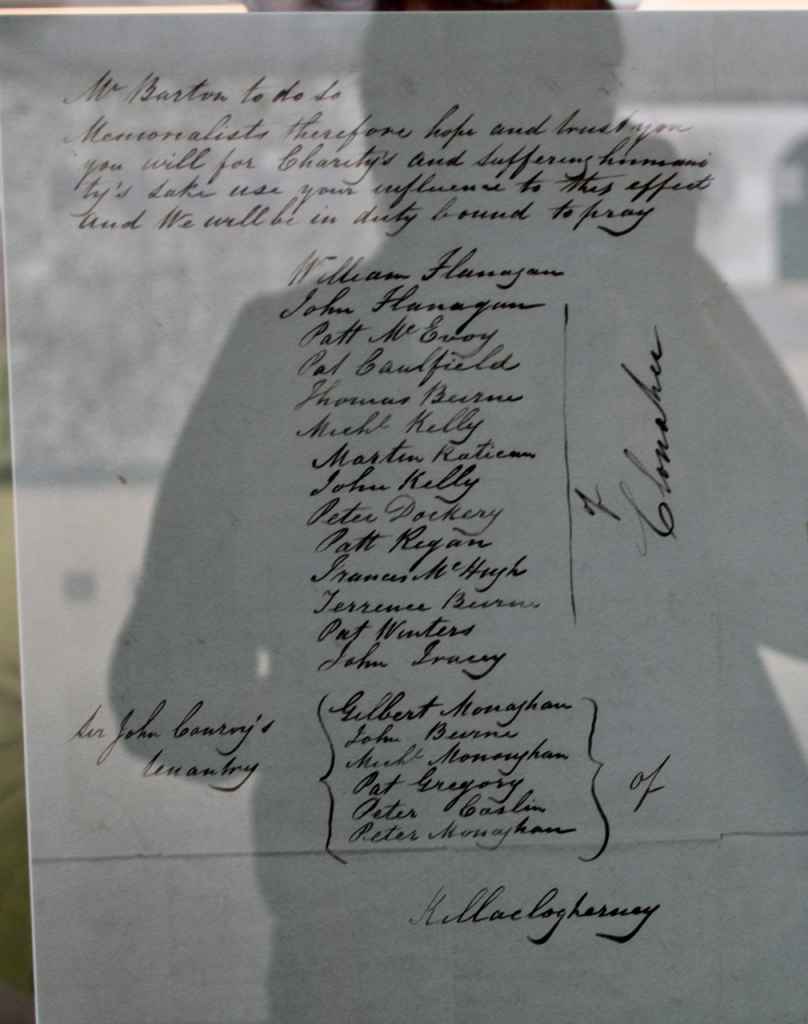

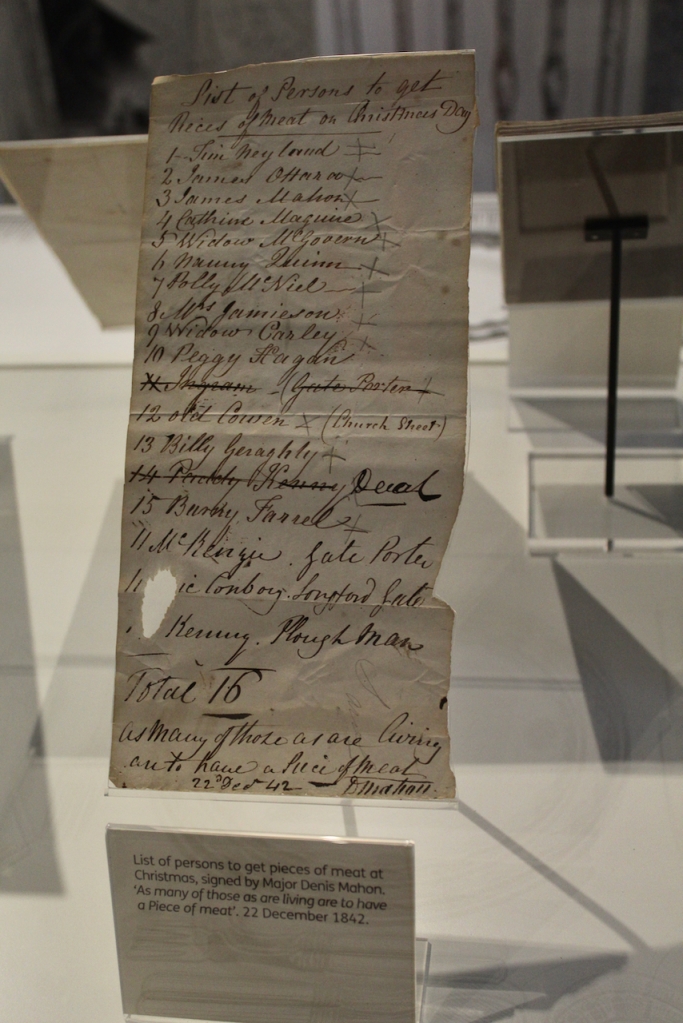

During the Famine, Alexander’s wife Jane sought to alleviate the suffering of the poor and she died of cholera or typhus in 1847.

When Alexander died in 1858, his son Philip was unable to afford the death duty tax and he had to sell the property. The house was bought by the Hall-Dares of Newtownbarry, County Wexford.

The Hall-Dares did not remain owners for long. After they evicted some tenants, these tenants actively sought the return of the Perceval family. Four years after Philip Perceval’s sale of the house, his brother Alexander, who had made a fortune in business in Hong Kong, re-acquired the property. Philip had married and moved to Scotland. Alexander brought back many of the dispossessed families from America and Britain, gave them back their land and re-roofed their homes. [see 2]

In the 1860s Alexander Perceval enlarged and embellished the house, hiring Johnstone and Jeane of London. He added a higher two storey seven bay block of limestone ashlar on the right (north) side of the house, which formed a new entrance front, knocking down a north wing in the process. [see 2]

Fitzgerald and Guinness tell us that Alexander also commissioned the company to design and build the furniture for the entire house.

The newer entrance has a large arched single-storey porte-cochére with coupled engaged Doric columns at its corners and two small arched side windows. Above is another pedimented Wyatt window in a larger pediment over two pairs of Ionic pilasters. The centre windows on either side of the porte-cochére on the ground floor are pedimented and on the upper storey the centre windows have curved arch pediments. The other windows have flat entablatures.

To the right of the newer front is a single storey two bay wing slightly recessed. The house is topped with a balustraded roof parapet.

Looking toward the south facade, we see a three-bay three storey section of the house, as well as more beyond to the west. The windows on the ground floor of the east and south elevations have corbelled pilasters.

The house is said to have over ninety rooms!

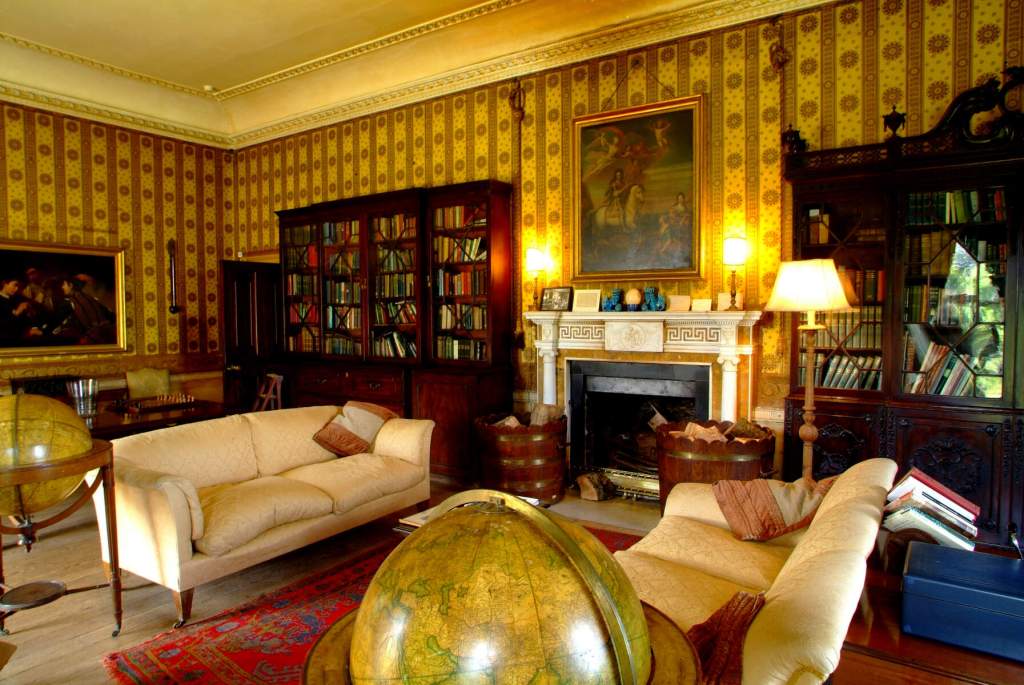

We gathered inside the front hall for the tour, with its impressive tiled floor and geometrically patterned ceiling. It has carved decorative doorcases and arched carved and shuttered side lights by the front door, and a large window facing the front door lights the room.

The ceiling has a Doric freize and a rose of acanthus leaves. A collection of stuffed birds and trophies line the wall, and a fine chimneypiece original to the house. [see 2]

Alexander did not get to enjoy his renovated home for long, as he died in 1866 of sunstroke, which occurred while fishing in the lake by the house. His wife lived a further twenty years. His son Alec (1859-1887) married a neighbour, Charlotte Jane O’Hara from Annaghmore.

From the front hall we entered the top-lit double-height vestibule with a grand sweeping staircase and gallery lined with paintings of ancestors.

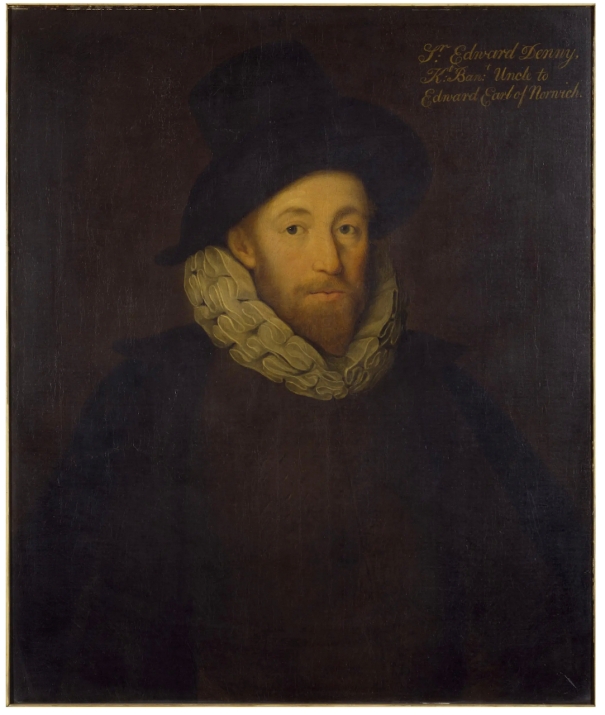

I’m dying to know who features in the wonderful portraits. The vestibule is so impressive, it is hard to know where to look! The ceiling has intricate detail.

The upper level of the stair hall is lined with arches and Corinthian pilasters.

When Alec died of meningitis in 1887, Charlotte took over the running of the estate for 30 years. Alec’s son Alexander Ascelin was injured in the first world war. He married the doctor’s daughter, Nora MacDowell. In financial difficulty, he had to sell some of the land. His wife predeceased him and toward the end of his life, he lived alone in this house of about ninety seven rooms, living in only three rooms. The rest of the house was closed up, dustsheets over the furniture.

The gasolier lamps remind us that the property generated its own gas at one time.

Five years after being closed up, in 1953, Ascelin’s son Alex, who had been a tea planter in what was then known as Burma, returned with his wife Yvonne to run the estate. They renovated the house, patched up the roof and installed a new kitchen. Alex modernised the farm.

It was their son Sandy and his wife who decided to take advantage of the size of the house to run a bed and breakfast, which opened in 1980. In 2004 their son Roderick returned to Temple House with his wife and children and took over running the business and the farm.

Roderick told us about the family as we toured the stair hall vestibule, drawing room and dining room, then brought us across the front hall to the newly renovated part of the house, which includes a former gun room passage. He managed to find craftsmen to do repairs, including the windows, moulding and plasterwork. After the tour, he kindly let us wander around the house, including up to the bedrooms.

Guinness and Fitzgerald tell us about the bedrooms:

“The bedrooms are immense. They all have their own bathrooms and a wonderful collection of matching furniture; in each of them a different wood has been used. The individual character of oak and beech and mahogany and others are evident as you stroll from one bedroom to the next. There are magnificent wardrobes – in one room it is 22 ft long – beds, sideboards, dressing tables, chairs. The largest of the bedrooms is so impressive it is called the “Half Acre.”” [see 2]

We exited through the morning room, which has a tall glass door, the original marble chimneypiece and impressive acanthus leaf ceiling rose.

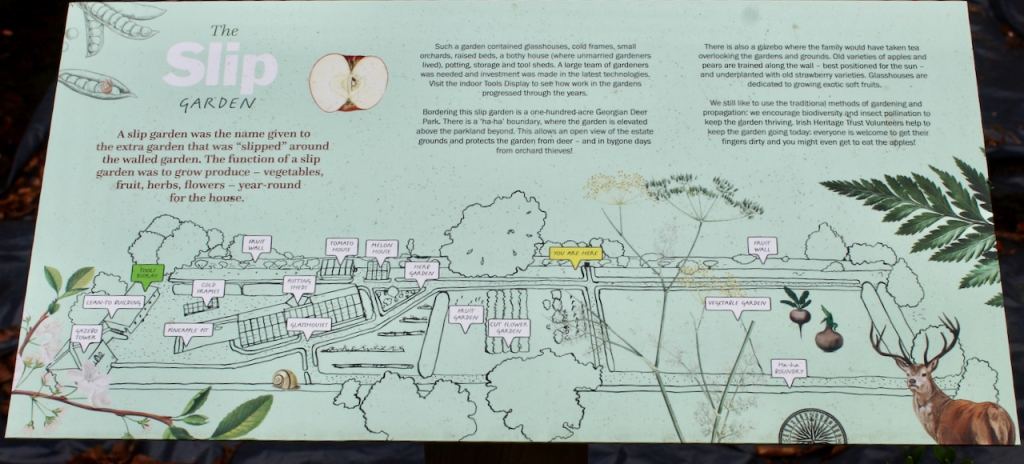

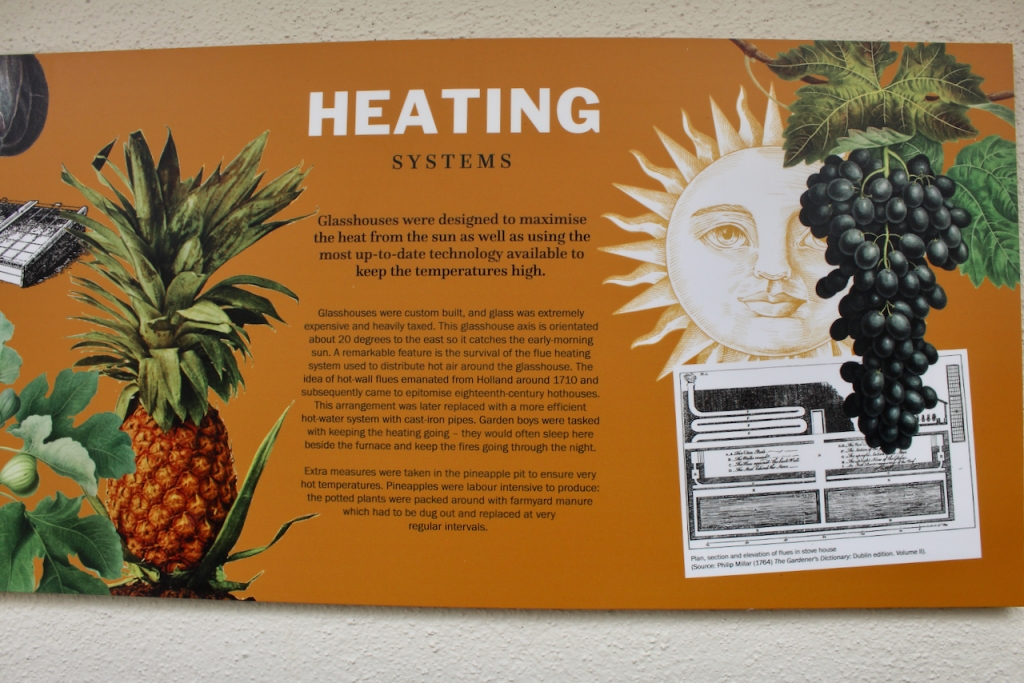

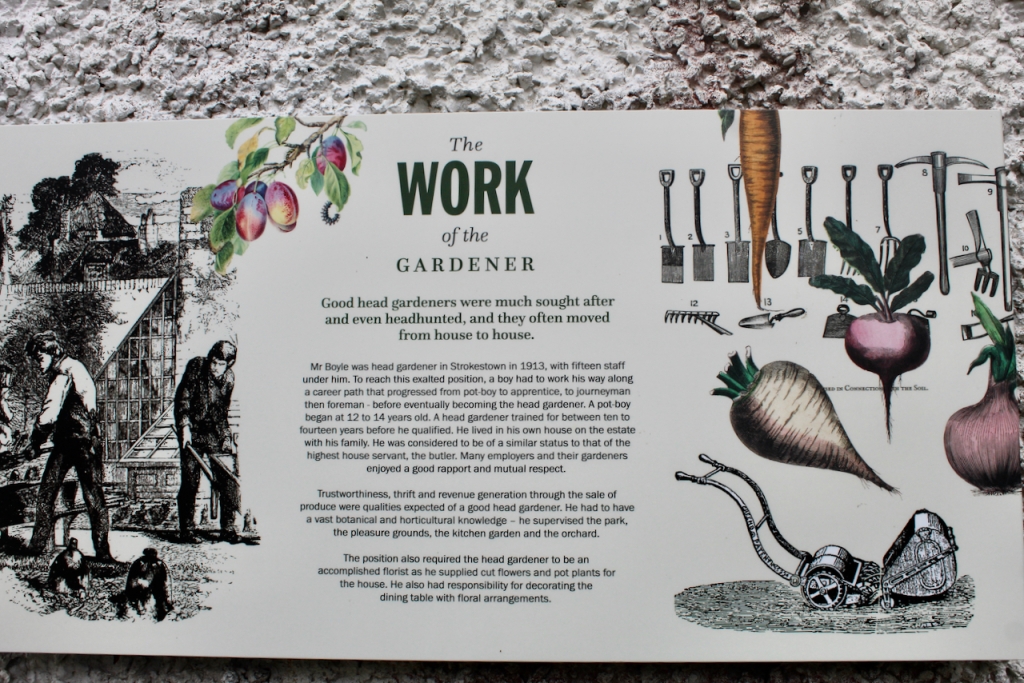

There is a walled kitchen garden which unfortunately we did not get to visit, where food is grown, including old varieties of apple, plum, pear and fig, and a stable yard. The Percevals preserve most of the 600 acres of old woods and the bogs in their natural state, and they also farm a further 600 acres.

[1] Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[2] Great Irish Houses. Forewards by Desmond FitzGerald, the Knight of Glin, and Desmond Guinness. Photographs by Trevor Hart. IMAGE Publications, 2008.

[3] Book Review by Peter Harbison, History Ireland issue 5 (Sept Oct 2016), volume 24.

[4] https://theirishaesthete.com/2018/05/14/thinking-big/

[6] http://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Temple%20House

[7] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2018/01/temple-house.html