https://www.powerscourtcentre.ie/

Open in 2025: all year, except New Year’s Day, Christmas Day, 10am-6pm

Fee: Free

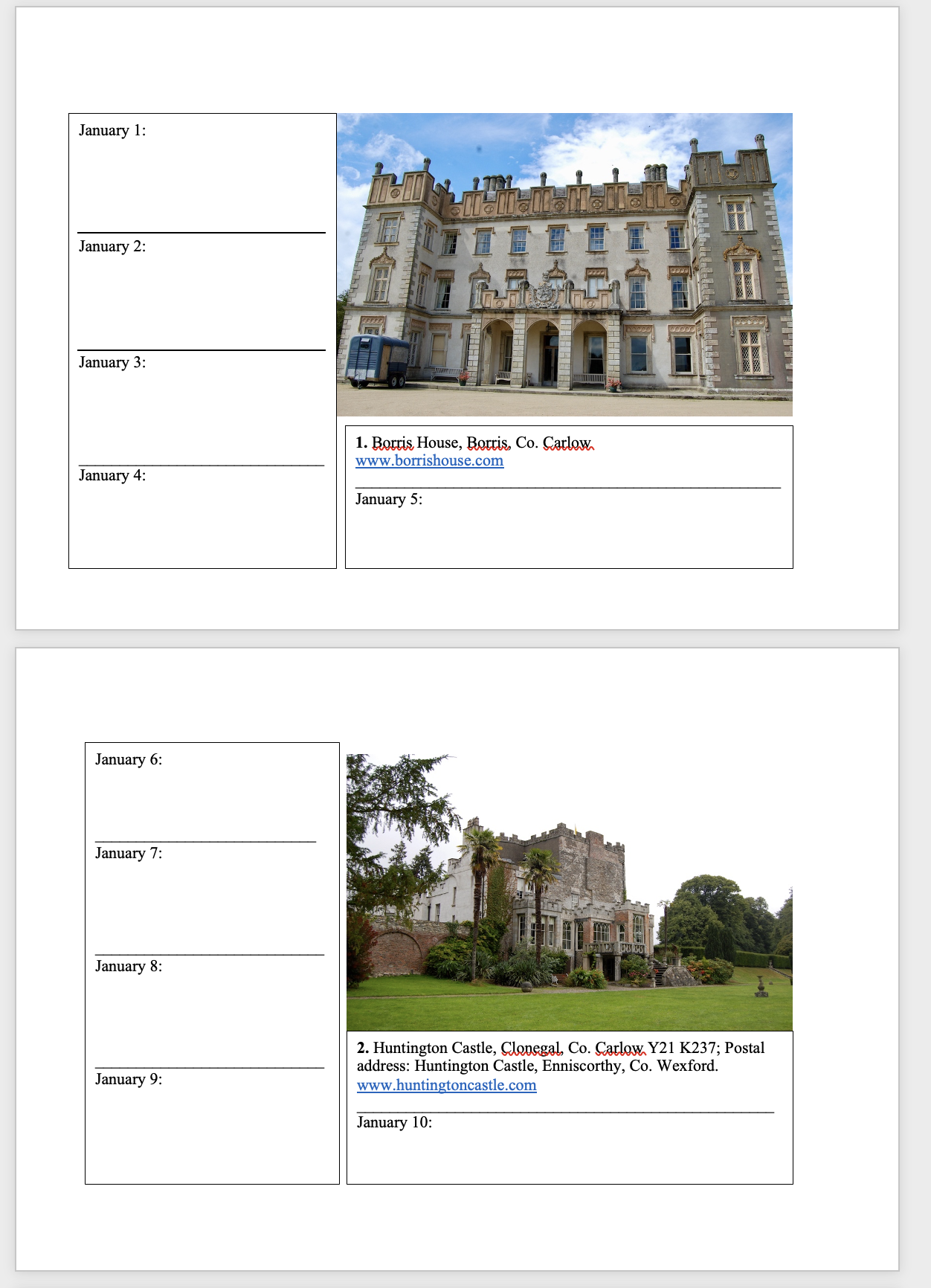

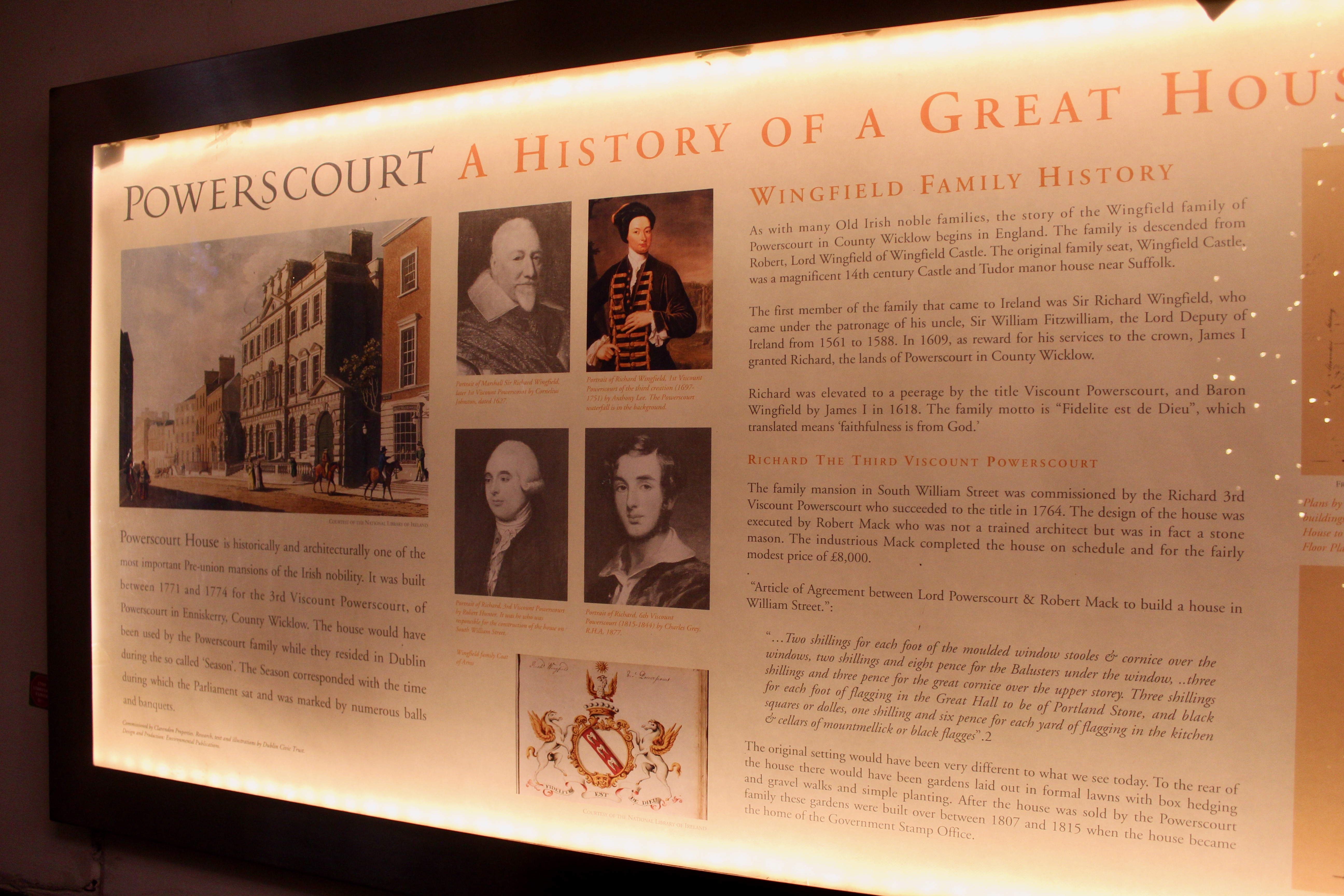

This house was built for the 3rd Viscount Powerscourt, Richard Wingfield (1730-1788), in 1771, as his city residence. He already owned the Wicklow estate and grand house of Powerscourt in Enniskerry (see my entry for more about the Wingfield family and the Viscounts Powerscourt). I came across the Wingfield family first on my big house travels in 2019, when Stephen and I visited Salterbridge House in Cappoquin, County Waterford, which is owned by Philip and Susan Wingfield (Philip is the descendent of the 3rd Viscount Powerscourt, by seven generations! [1]).

Kevin O’Connor writes in his Irish Historic Houses that “The palazzo was originally laid out around an open square. This has now been fitted (and covered) in to provide a centre specialising as a grand emporium for crafts, antiques, shopping and restaurants.”

I am writing this blog during the Covid-19 lockdown in March 2020! I started to take pictures of Powerscourt townhouse last December, when it was in its full glory inside with Christmas decorations, knowing that it is listed in section 482. Today I will write about the history of this house and share my photographs, although I have not yet contacted Mary Larkin, who must manage the Townhouse Centre. Last week before the lockdown, when most of Ireland and the world were already self-isolating and most shops were closed, Stephen and I walked into town. It was a wonderful photographic opportunity as the streets were nearly empty.

Above, by the wall of our favourite pub, Grogans, is the picture of the James Malton engraving (1795) of the neo-Palladian Powerscourt Townhouse. This sign tells us that the house was begun in 1771 and completed in 1774 and cost £8000.

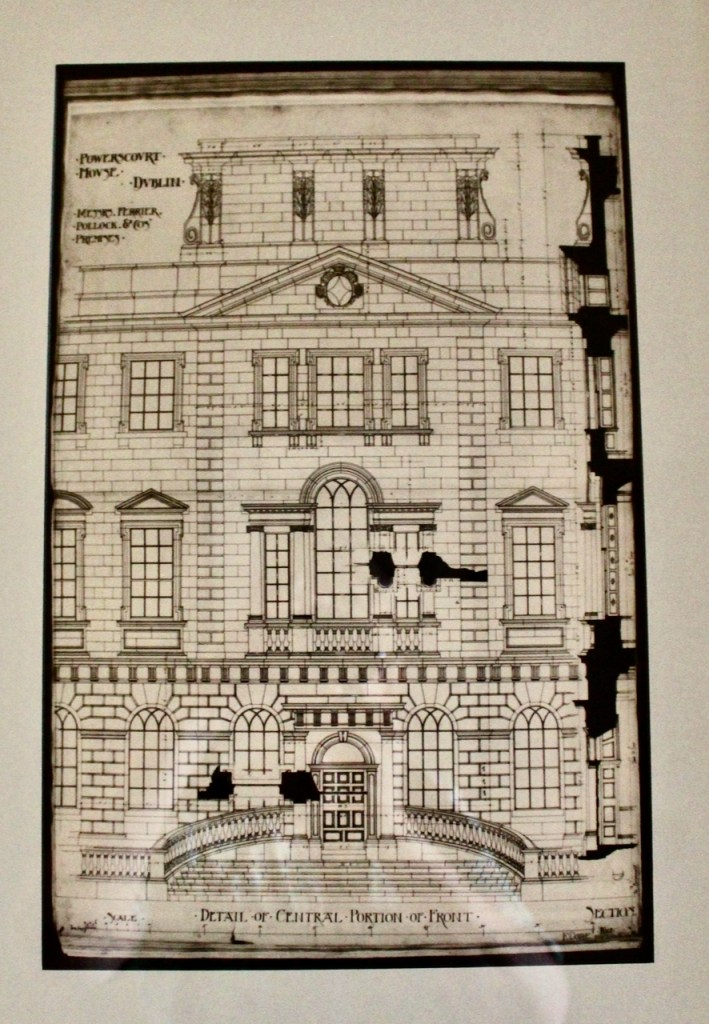

Architectural historian Christine Casey describes Powerscourt Townhouse to be reminiscent of Richard Castle’s country-house practice, although she writes that it was designed by Robert Mack. [3] Mack was an amateur architect and stonemason. The west front of the house, Malton tells us, is faced with native stone from the Wicklow estate, with ornament of the more expensive Portland stone, from England.

The house is historically and architecturally one of the most important pre-Union mansions of the Irish nobility. The Wingfields, Viscount Powerscourt and his wife Lady Amelia Stratford (daughter of John, Earl of Aldborough), would have stayed in their townhouse during the “Season,” when Parliament sat, which was in the nearby College Green in what is now a Bank of Ireland, and they would have attended the many balls and banquets held during the Season.

Richard was the younger son of the 1st Viscount Powerscourt, and he inherited the title after his older brother, Edward, died. He was educated in Trinity College, Dublin, and the Middle Temple in London. He served in the Irish House of Commons for Wicklow County from 1761-1764. In 1764 he became 3rd Viscount after the death of his brother, and assumed his seat in the Irish House of Lords.

The arch to the left of the house was a gateway leading to the kitchen and other offices and there is a similar gateway on the right, which led to the stables.

The house has four storey over basement frontage to South William Street, with “stunted and unequal niched quadrants” (see this in the photograph above, between the main block of the house, and the gateway) and pedimented rusticated arches. [4][5] Christine Casey describes the nine bay façade as faced with granite, and it has an advanced and pedimented centrepiece crowned by a solid attic storey with enormous volutes like that of Palladio’s Villa Malcontenta [5].

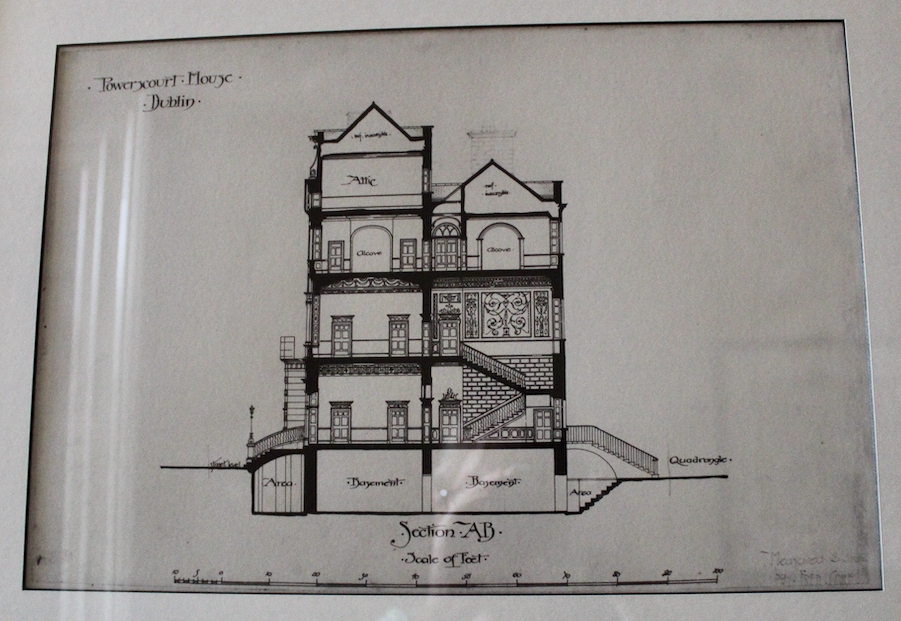

The attic storey housed an observatory. From this level, one could see Dublin Bay.

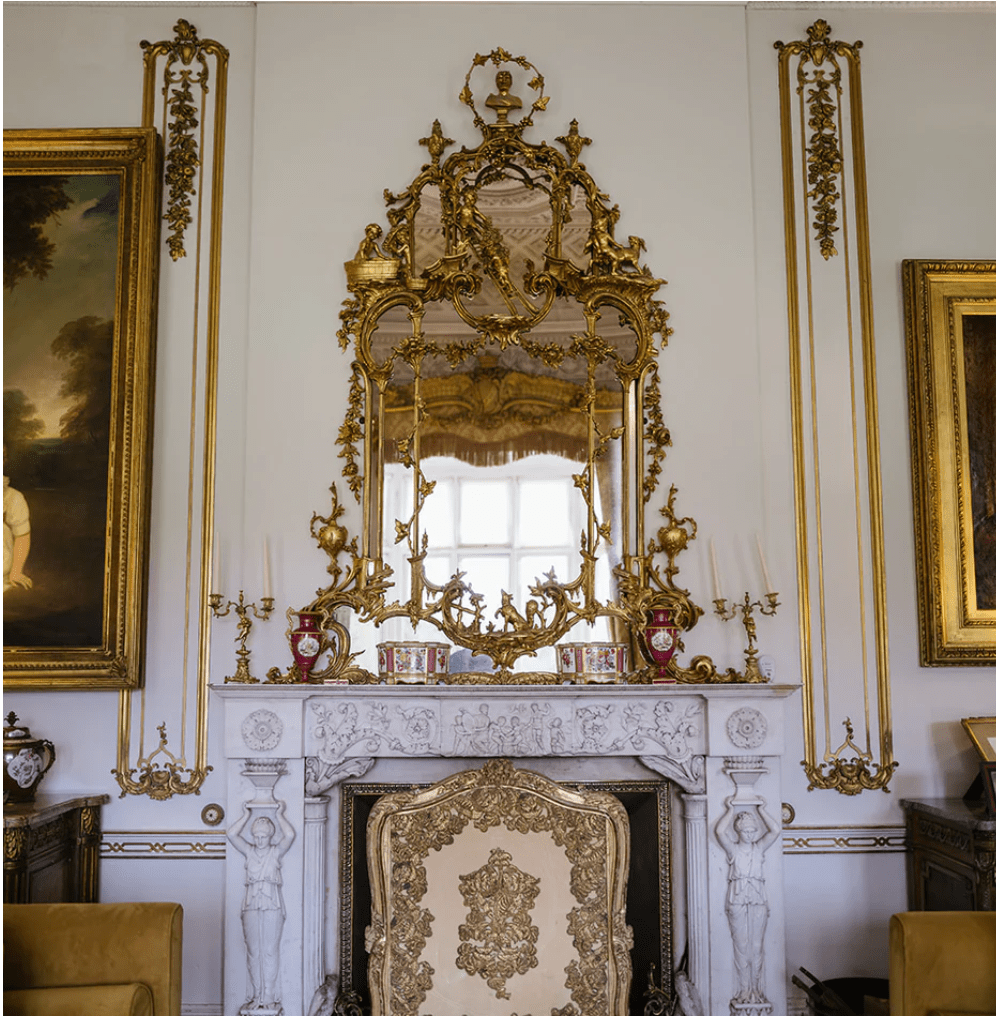

The ground floor has round-headed windows, while the piano nobile has alternating triangular and “segment-headed” pediments. A “Piano nobile” is Italian for “noble floor” or “noble level”, also sometimes referred to by the corresponding French term, bel étage, and is the principal floor of a large house. This floor contains the principal reception and bedrooms of the house. There is a Venetian window and tripartite window over the doorcase. Mark Bence-Jones tells us a Venetian window had three openings, that in the centre being round-headed and wider than those on either side; it is a very familiar feature of Palladian architecture.

The ground floor contained the grand dining room, the parlour, and Lord Powerscourt’s private rooms. Ascending to the first floor up the magnificent mahogany staircase, one entered the rooms for entertaining: the ballroom and drawing room.

An information board inside the house quotes the “Article of Agreement” between Lord Powerscourt and the stonemason Robert Mack:

“Two shillings for each foot of the moulded window stooles and cornice over the windows, two shillings and eight pence for the Balusters under the windows… three shillings and three pence for the great cornice over the upper storey. Three shillings for each foot of flagging in the Great Hall to be of Portland Stone, and black squares or dolles, one shilling and six pence for each yard of flagging in the kitchen and cellars of mountmellick or black flagges.”

This information board also tells us that the original setting of the house would have been a garden to the rear of the house, laid out in formal lawns with box hedging and gravel walks.

When one walks up the balustraded granite steps leading to the front door, through the hall and past the mahogany staircase, one enters what was the courtyard of the house.

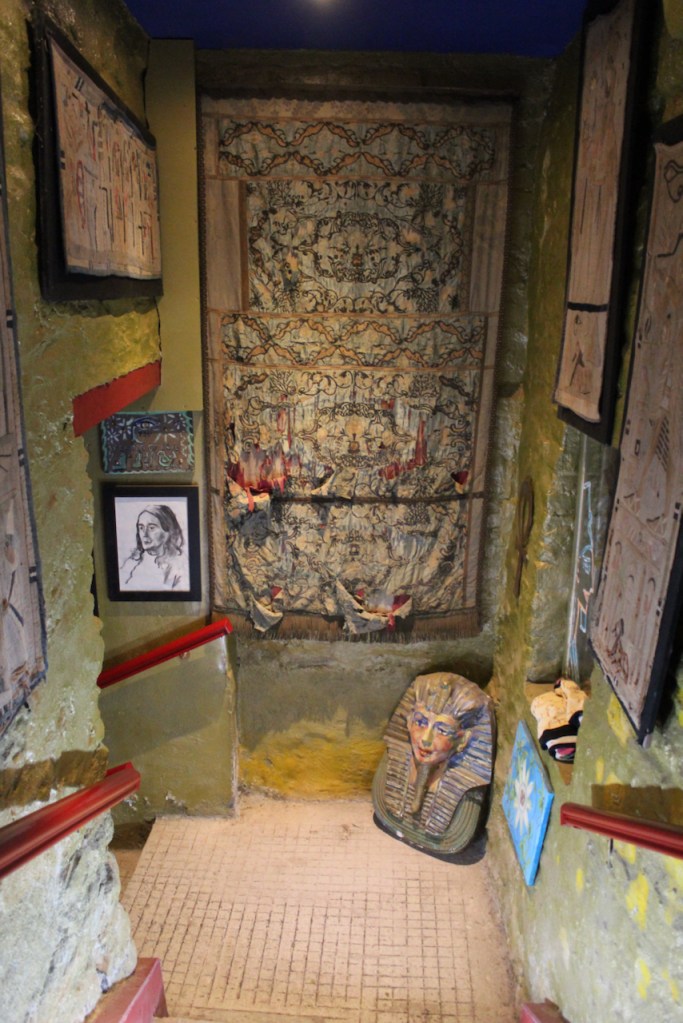

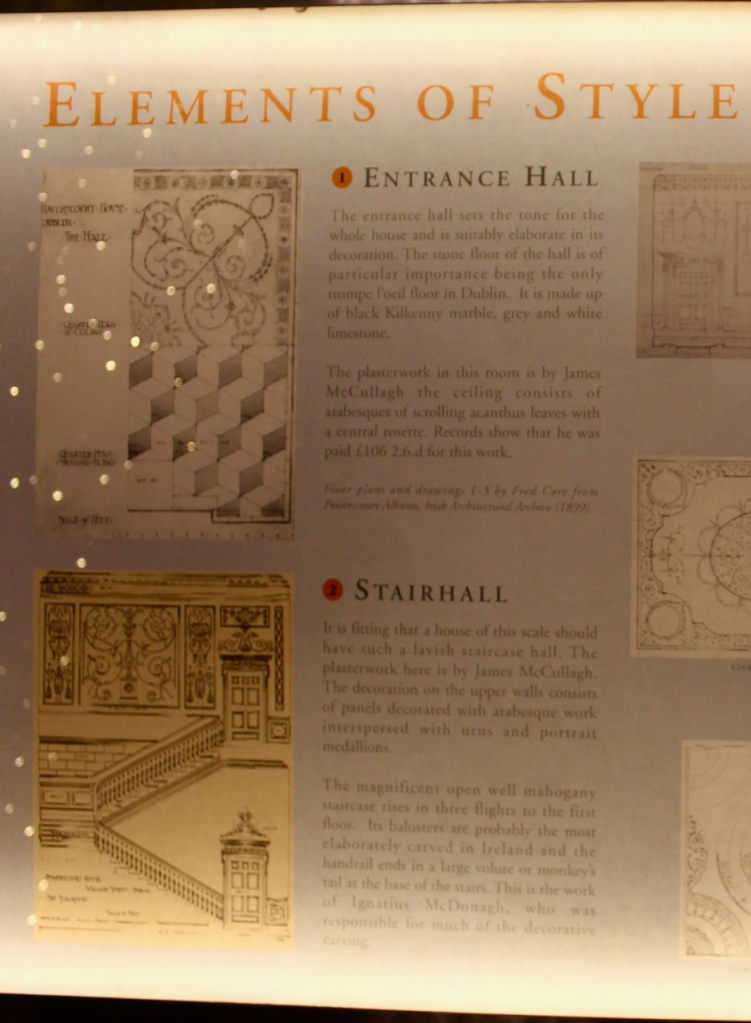

You can see the “trompe l’oeil” floor in the entrance hall in the photo below, made up of black Kilkenny marble, grey and white limestone.

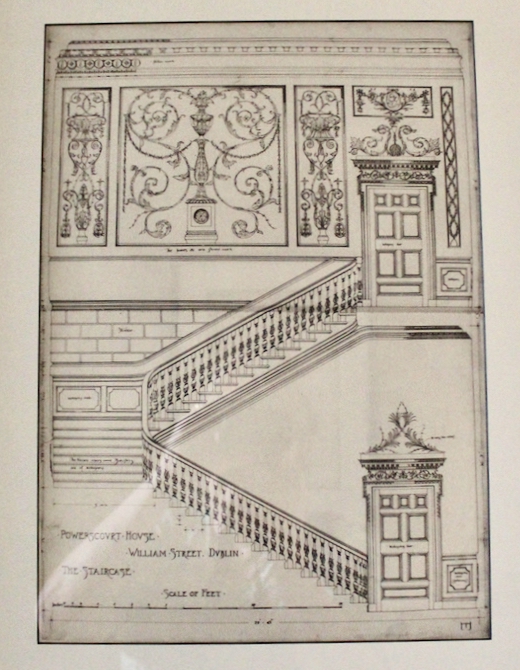

The mahogany staircase rises in three flights to the first floor. The balusters are probably the most elaborately carved in Ireland, and the handrail ends in a large volute or “monkey’s tail” at the base of the stairs. The woodwork carving is by Ignatius McDonagh. I need to go back to take a better picture of the balustrade. We saw an even larger “monkey tail” volute end of a staircase in Barmeath (another section 482 property, see my entry), more like a dragon’s tail than a monkey, it was so large!

The Wingfield family descended from Robert, Lord Wingfield of Wingfield Castle in England, near Suffolk. The first member of the family who came from England was Sir Richard Wingfield, who came under the patronage of his uncle, Sir William Fitzwilliam, the Lord Deputy of Ireland from 1561 to 1588. In 1609 King James I granted Richard Wingfield, in reward for his services to the Crown, the lands of Powerscourt in County Wicklow. Richard was a military adventurer, and fought against the Irish, and advanced to the office of Marshal of Ireland. In May 1608 he marched into Ulster during “O’Doherty’s Rebellion” against Sir Cahir O’Doherty, and killed him and dispersed O’Doherty’s followers. For this, he was granted Powerscourt Estate, in 1609. [7]

In 1618 James I raised Richard to the Peerage as Viscount Powerscourt, Baron Wingfield. The family motto is “Fidelite est de Dieu,” faithfulness is from God.

Richard the 3rd Viscount Powerscourt succeeded to the title in 1764. He was not a direct descendant of the 1st Viscount Powerscourt. Richard the 1st Viscount had no children, so the peerage ended with the death of the 1st Viscount.

The Powerscourt estate in Wicklow passed to his cousin, Sir Edward Wingfield, a distinguished soldier under the Earl of Essex (Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex), and a person of great influence in Ireland. [8] Essex came to Ireland to quell a rebellion that became the Nine Years’ War. Sir Edward Wingfield married Anne, the daughter of Edward, 3rd Baron Cromwell (descendent of Henry VIII’s Thomas Cromwell). [9] It was this Edward Wingfield’s grandson Folliot (son of Richard Wingfield), who inherited the Powerscourt estates, for whom the Viscountcy was revived, the “second creation,” in 1665. [10]

However, once again the peerage expired as Folliot also had no offspring. Powerscourt Estate passed to his cousin, Edward Wingfield. Edward’s son Richard (1697-1751) of Powerscourt, MP for Boyle, was elevated to the peerage in 1743, by the titles of Baron Wingfield and Viscount Powerscourt (3rd Creation).

This Richard Wingfield was now the 1st Viscount (3rd creation). He married, first, Anne Usher, daughter of Christopher Usher of Usher’s Quay, but they had no children. He married secondly Dorothy, daughter of Hercules Rowley of Summerville, County Meath. Their son, Edward, became the 2nd Viscount. When he died in 1764, Richard, his brother, became 3rd Viscount. Seven years after inheriting the title, Richard 3rd Viscount began the building of Powerscourt Townhouse.

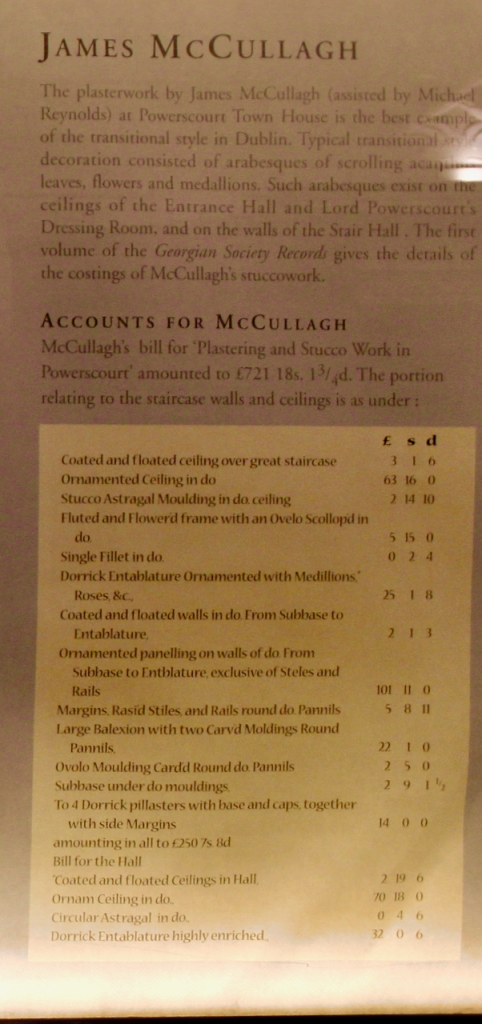

Inside just past the entrance hall, we can still climb the staircase and see the wonderful plasterwork by stuccodores James McCullagh assisted by Michael Reynolds.

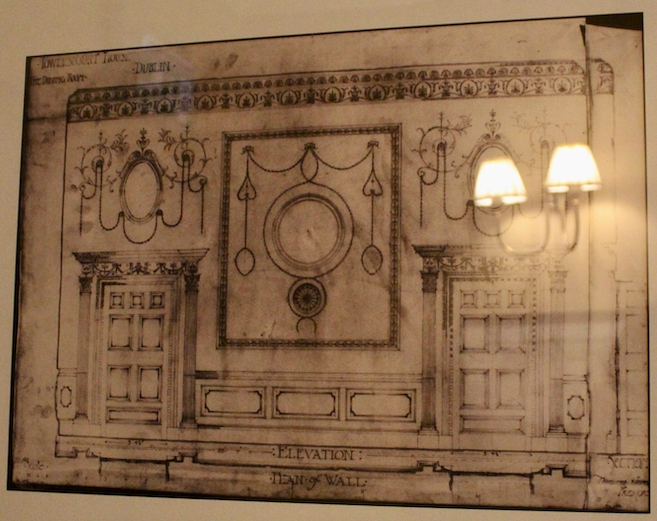

The decoration on the upper walls consists of panels decorated with arabesque work interspersed with urns, acanthus scrolls [6], palms and portrait medallions. I haven’t discovered who is pictured in the portraits! Neither Christine Casey nor the Irish Aesthete tell us in their descriptions.

Ionic pilasters frame two windows high up in the east wall – we can see one in the photograph above. The lower walls are “rusticated in timber to resemble stone,” Casey tells us. I would have assumed that the brickwork was of stone, not of timber.

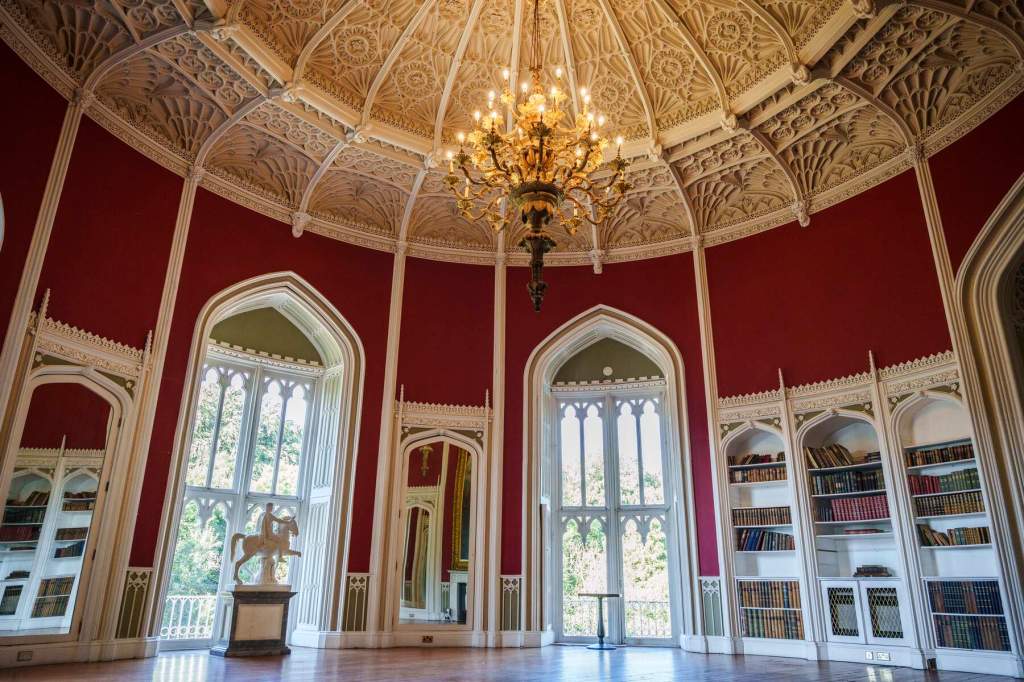

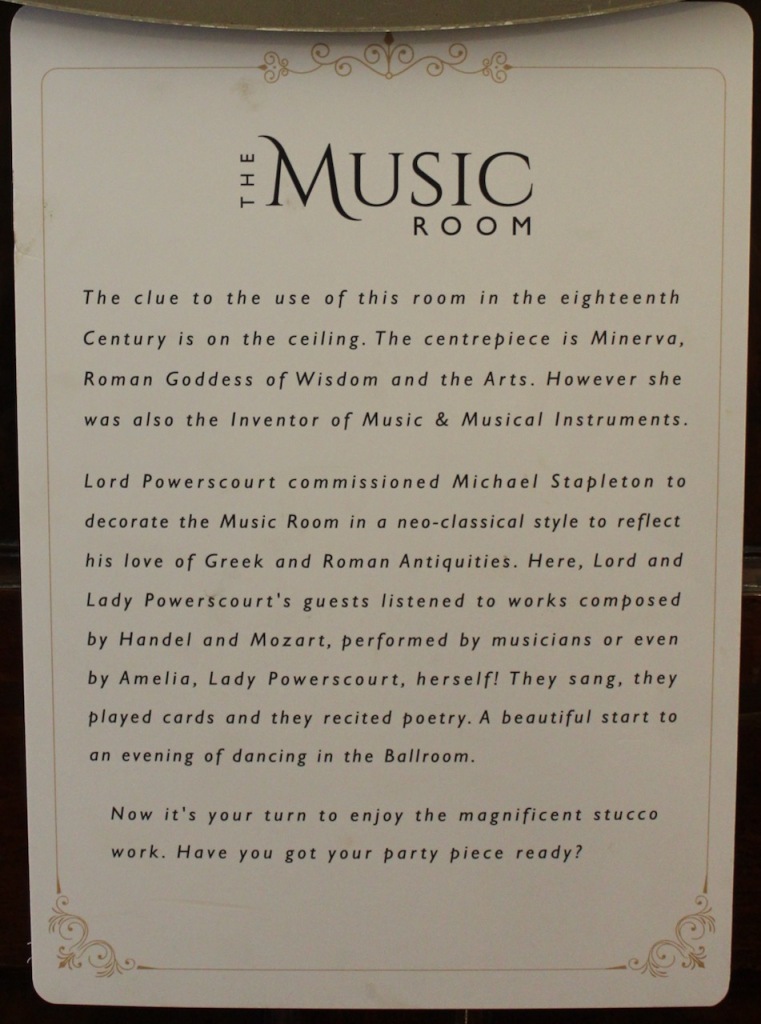

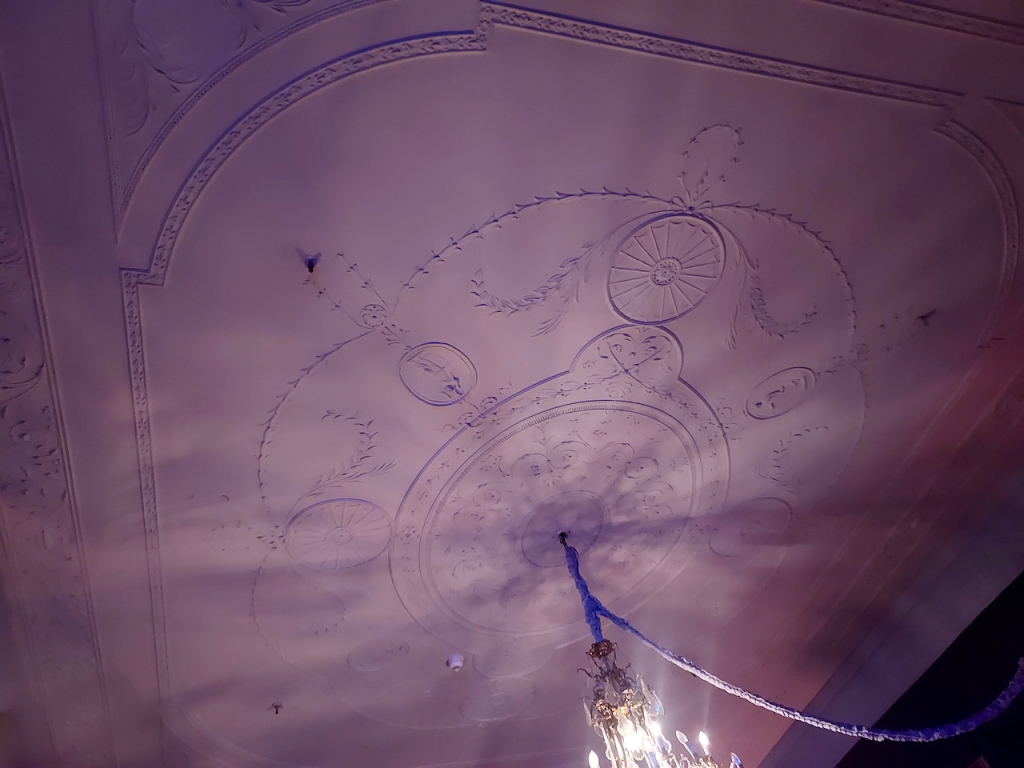

No expense was spared in furnishing the house. As well as the rococo plasterwork on the stairs there was neo-Classical work by stuccodore Michael Stapleton. According to the information board, much of the more sober neo-Classical work was cast using moulds, no longer created freehand the way the rococo plasterwork was done. The neo-Classical work was called the Adams style and in Powerscourt Townhouse, was created between 1778-1780. Stapleton’s work could have been seen in the Dining Room, Ballroom, Drawing room and Dome Room.

The ceiling in a room now occupied by The Town Bride, which was the original music room, and the ballroom, now occupied by the Powerscourt Gallery, contain Stapleton’s work.

The Dome Room is now behind glass.

To see the Dining Room and Parlour, you must enter through one of the side carriage entrances, to the restaurant Farrier and Draper.

The townhouse website tells us that Richard Wingfield was known as the “French Earl” because he made the Grand Tour in Europe and returned wearing the latest Parisian fashions. He died in 1788 and was laid out in state for two days in his townhouse, where the public were admitted to view him! His son Richard inherited the title and estates.

The garden front is of seven bays rather than nine, and has a broader three-bay advanced centrepiece.

After the house was sold by the Powerscourt family the gardens were built over between 1807 and 1815, when the house became the home of the Government Stamp Office. After the Act of Union, when the Irish Parliament was abolished and Ireland was ruled by Parliament in England, many Dublin mansions were sold. In July 1897 Richard 4th Lord Powerscourt petitioned Parliament to be allowed to sell his house to the Commissioner of Stamp Duties. The house was described as black from “floating films of soot” produced by the city’s coal fires. I can remember when Trinity was blackened by soot also before smoky coal was banned from Dublin, and extensive cleaning took place.

Several alterations were made to make the house suitable for its new purpose. This work was carried out by Francis Johnston, architect of the Board of Works, who designed the General Post Office on O’Connell Street. He designed additional buildings to form the courtyard of brown brick in Powerscourt townhouse, which served as offices. This consisted of three ranges of three storeys with sash windows. He also designed the clock tower and bell on Clarendon Street.

In 1835, the Government sold the property to Messrs Ferrier Pollock wholesale drapers, who occupied it for more than one hundred years. It was used as a warehouse. I’m sure the workers in the warehouse enjoyed going up and down the grand staircase!

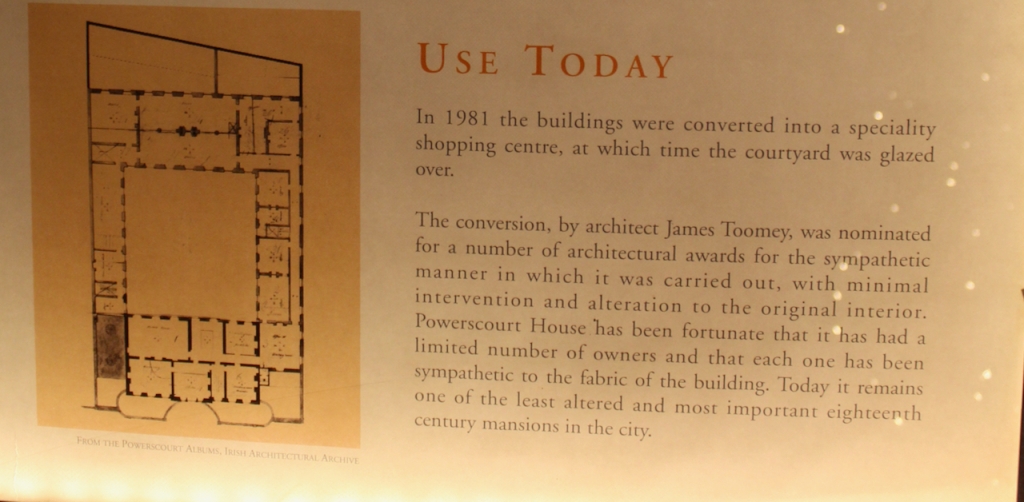

In 1981 the buildings were converted into a shopping centre, by architect James Toomey, for Power Securities. The courtyard was glazed over to make a roof.

Powerscourt Townhouse was one of my haunts when I first moved to Dublin in 1986 (after leaving Dublin, where I was born, in 1969, at eight months old). I loved the antique stores with their small silver treasures and I bought an old pocket watch mounted on a strap and wore it as a watch for years. My sister, our friend Kerry and I would go to Hanky Pancakes at the back of the town centre, downstairs, for lemon and sugar coated thin pancakes, watching them cook on the large round griddle, being smoothed with a brush like that used to clean a windshield. For years, it was my favourite place in Dublin. Pictured below is the pianist, an old friend of Stephen’s, Maurice Culligan. My husband bought my engagement ring in one of the antique shops!

Despite the very helpful information boards, I find it impossible to imagine what the original house looked like. I took pictures walking around the outside of the shopping centre.

The French Connection entrance side is opposite the Westbury Mall.

The grander side is opposite from Grogans, and next to the old Assembly House which is now the headquarters of the Irish Georgian Society. The walkway by Grogans leads down to the wonderful Victorian George’s Arcade buildings.

Donation

Help me to fund my creation and update of this website. It is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€10.00

[1] I traced the genealogy of the owner of Salterbridge, Philip Wingfield. I traced him back to the owners of Powerscourt Townhouse. Richard 4th Viscount Powerscourt (1762-1809) has a son, Reverend Edward Wingfield (his third son) (b. 1792). He marries Louise Joan Jocelyn (by the way, he is not the only Wingfield who marries into the Jocelyn family, the Earls of Roden). They have a son, Captain Edward Ffolliott Wingfield (1823-1865). He marries Frances Emily Rice-Trevor, and they have a son, Edward Rhys Wingfield (1848-1901). He marries Edith Caroline Wood, and they have a son, Captain Cecil John Talbot Rhys Wingfiend. He marries Violet Nita, Lady Paulett, and they have a son, Major Edward William Rhys Wingfield. It is he who buys Salterbridge, along with his wife, Norah Jellicoe. They are the parents of Philip Wingfield.

[3] Archiseek seems mistaken as identifying the architect to be Richard Castle/Cassells

http://archiseek.com/2010/1774-powerscourt-house-south-william-street-dublin/

[4] Casey, Christine. The Buildings of Ireland: Dublin. The City within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. Founding editors: Nikolaus Pevsner and Alistair Rowan. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2005.

pediment: “Originally the low-pitched triangular gable of the roof of a Classical temple, and of the roof of a portico; used as an ornamental feature, generally in the centre of a facade, without any structural purpose.”

portico: “an open porch consisting of a pediment or entablature carried on columns.”

entablature: “a horizontal member, properly consisting of an architrave, frieze and cornice, supported on columns, or on a wall, with or without columns or pilasters.”

architrave: “strictly speaking, the lowest member of the Classical entablature; used loosely to denote the moulded frame of a door or window opening.”

frieze: “strictly speaking, the middle part of an entablature in Classical architecture; used also to denote a band of ornament running round a room immediately below the ceiling.”

cornice: “strictly speaking, the crowning or upper projecting part of the Classical entablature; used to denote any projecting moulding along the top of a building, and in the angle between the walls and the ceiling of a room.”

pilasters: “a flat pillar projecting from a wall, usually with a capital of one of the principal Orders of architecture.”

volute: “a scroll derived from the scroll in the Ionic capital.”

Ionic Order: “the second Order of Classical architecture.”

Acanthus – decoration based on the leaf of the acanthus plant, which forms part of the Corinthian capital

[7]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Wingfield,_1st_Viscount_Powerscourt_(first_creation)

[8]http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/search/label/County%20Wicklow%20Landowners

I did further research in Burke’s Peerage to discover the exact relationship of these cousins. https://ukga.org/cgi-bin/browse.cgi?action=ViewRec&DB=33&bookID=227&page=bp189401283

Lewis Wingfield of Southampton married a Ms. Noon. He had a son Richard who married Christiana Fitzwilliam, and a son George. Richard the 1st Viscount who moved to Ireland is the son of Richard and Christiana. Edward Wingfield, who inherited Powerscourt Estate from Richard 1st Viscount, was the grandson of George (son of Lewis of Southampton), son of Richard Wingfield of Robertstown, County Limerick, who married Honora O’Brien, daughter of Tadh O’Brien (second son of Muragh O’Brien, 1st Lord Inchiquin).

[9] There was much intermarrying between the Cromwells and the Wingfields at this time! 1st Viscount Richard Wingfield, of the first creation, married Frances Rugge (or Repps), daughter of William Rugge (or Repps) and Thomasine Townshend, who was the widow of Edward Cromwell, 3rd Baron Cromwell. Frances Rugge and Edward Cromwell had two daughters, Frances and Anne. Frances Cromwell married Sir John Wingfield of Tickencote, Rutland, and Anne Cromwell married Sir Edward Wingfield of Carnew, County Wicklow. Anne and Edward’s grandson Folliott became the 1st Viscount Powerscourt of the 2ndcreation.

[10] Wikipedia has a different genealogy from Lord Belmont’s blog. Folliott Wingfield, 1st Vt of 2nd creation (1642-1717), according to Wikipedia, is the son of Richard Wingfield and Elizabeth Folliott, rather than the son of Anne Cromwell and Edward Wingfield of Carnew, County Wicklow, as the Lord Belmont blog claims. Burke’s Peerage however, agrees that Folliott Wingfield, 1st Vt 2nd Creation is not the son of Edward Wingfield of Carnew.

According to Burke’s Peerage, Edward Wingfield of Carnew, who married Anne Cromwell, and who inherits Powerscourt Estate, dies in 1638. They have six sons:

I. Richard is his heir;

II. Francis

III. Lewis, of Scurmore, Co Sligo, who married Sidney, daughter of Paul Gore, 1st Bart of Manor Gore, and they have three sons: Edward*, Lewis and Thomas. This Edward inherits Powerscourt Estate.

IV. Anthony, of London

V. Edward, of Newcastle, Co Wickow, d. 1706

Richard (d. 1644 or 1645), the heir, married Elizabeth Folliott, and is succeeded by his son Folliott Wingfield, who becomes 1st Vt, 2nd Creation. When he dies, the peerage ends again. However, his first cousin, Edward* inherits Powerscourt. Edward Wingfield Esq, of Powerscourt, Barrister-at-Law, marries first Eleanor Gore, daughter of Arthur Gore of Newtown Gore, County Mayo, and by her has a son, Richard. Richard inherited Powerscourt, became an MP and was elevated to the peerage in 1743, and became (1st) Viscount Powerscourt of the 3rd creation.

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com