Today I am going to write about Woodbrook as it is provides holiday accommodation. In 2026, it is no longer on the Revenue Section 482 list.

donation

Help me to pay the entrance fee to one of the houses on this website. This site is created purely out of love for the subject and I receive no payment so any donation is appreciated!

€15.00

Then, below my entry, I have listed Section 482 properties that are open for a visit in March 2025!

Woodbrook looks like a lovely place to stay and the hosts Giles and Alexandra Fitzherbert, who have lived there since 1998, serve dinner also if requested. Giles is a former Ambassador in South America and his wife Alexandra is of Anglo-Italian-Irish-Chilean extraction, the Hidden Ireland website tells us.

Woodbrook house was built in the 1770s. It was built by Reverend Arthur Jacob (1717-1786), Archdeacon of Armagh, for his daughter Susan and her husband Captain William Blacker, a younger son of the family at Carrigblacker near Portadown. Arthur Jacob was Rector of Killanne in County Wexford while he was also Archdeacon of Armagh. [2]

The Historic Houses of Ireland website tells us:

“Nestling beneath the Backstairs Mountains near Enniscorthy in County Wexford, Woodbrook, which was first built in the 1770s, was occupied by a group of local rebels during the 1798 rebellion. Allegedly the leader was John Kelly, the ‘giant with the gold curling hair’ in the well known song ‘The Boy from Killanne’. It is said that Kelly made a will leaving Woodbrook to his sons but he was hanged on Wexford bridge, along with many others after the rebels defeat at Vinegar Hill. He was later given an imposing monument in nearby Killanne cemetery.” [3]

Another rebel who occupied the house in 1798 was John Henry Colclough (c.1769-98) who was also executed for his participation in the 1798 Insurrection.

The Historic Houses of Ireland site continues:

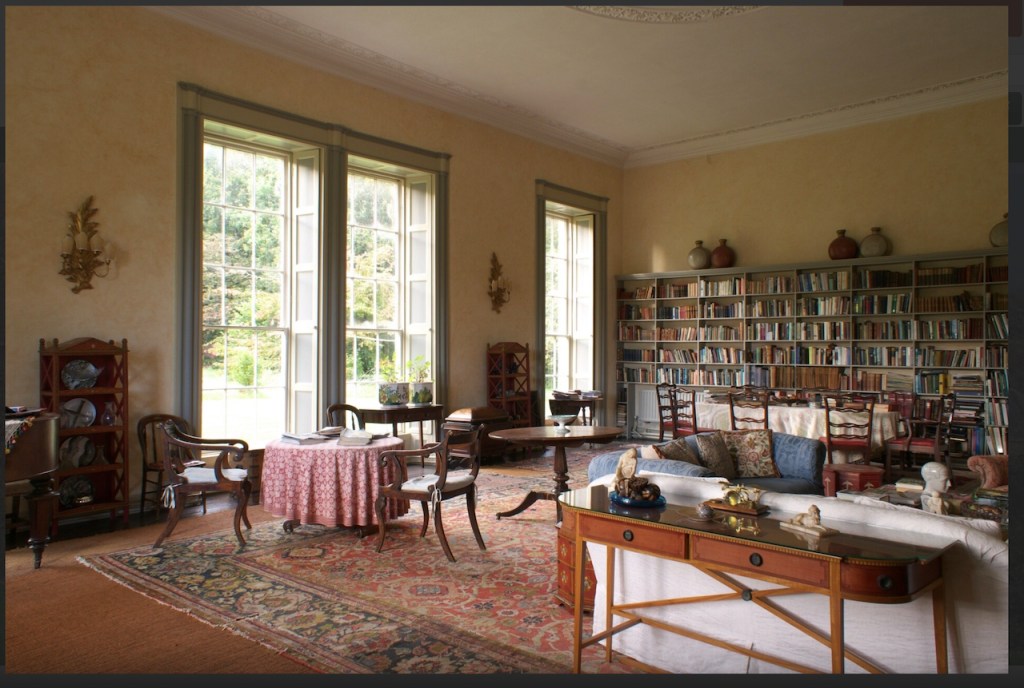

“… The house was badly knocked about by the rebels and substantially rebuilt in about 1820 as a regular three storey Regency pile with overhanging eaves, a correct Ionic porch surmounted by a balcony and three bays of unusually large Wyatt windows on each floor of the facade.” [3]

The house has tripartite entrance doorcase with large cobweb fanlight under the portico. Mark Bence-Jones writes that the hall has a “rather Soanian vaulted ceiling.” I’m not sure what he means by this – if you can enlighten me, please do let me know! He also comments on the “very spectacular spiral flying staircase of wood, with wrought iron balustrades; a remarkable and brilliant piece of design and construction.” [4] It is called “flying” because it does not touch the walls. The steps look like stone but are timber, and each was carefully made to fit perfectly together. Robert O’Byrne tells us that the stairs bounce slightly as one walks up or down, which sounds disconcerting!

Woodbrook passed to the son, William Blacker (1790-1831). He married Elizabeth Anne Carew, from Castleboro House in County Wexford, now a splendid ruin.

William and Elizabeth Anne’s son Robert Shapland Carew Blacker (1826-1913) inherited the impressive Carrickblacker house in County Armagh from his relatives, as well as inheriting Woodbrook, from an elder brother, William Jacob, who predeceased him and had no children. William Jacob Blacker served as High Sheriff of County Wexford.

Robert Shapland married, in 1858, Theodosia Charlotte Sophia, daughter of George Meara, of May Park, County Waterford. Carrickblacker house remained in the family until the estate was purchased in 1937 by Portadown Golf Club, which demolished Carrickblacker House in 1958 to make way for a new clubhouse. [5]

The eldest son, William Robert George Blacker, died at just twenty years old. The next eldest, Edward Carew Blacker, died unmarried in 1932. He also served as High Sheriff of County Wexford. After his death, Woodbrook lay empty for some years, inherited by Edward’s brother Stewart Ward William Blacker, who also owned Carrickblacker. The Irish Historic Houses website tells us that the house was occupied by the Irish army during the Second World War.

The house has a large drawing room with a chimneypiece that is from the original house.

Stewart’s son Robert Stewart Blacker moved to the house in the 1950s after Carrickblacker was sold, and Woodbrook was then extensively modernised.

Also featured in The Wexford Gentry by Art Kavanagh and Rory Murphy. Published by Irish Family Names, Bunclody, Co Wexford, Ireland, 1994.

and The Irish Aesthete: Buildings of Ireland, Lost and Found. Robert O’Byrne. The Lilliput Press, Dublin, 2024.

Donation towards accommodation

I receive no funding nor aid to create and maintain this website, it is a labour of love. I travel all over Ireland to visit Section 482 properties and sometimes this entails an overnight stay. A donation would help to fund my accommodation.

€150.00

[1] https://hiddenireland.com/house-pages/woodbrook-house/

[2] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/06/24/speaking-of-98/

[3] https://www.ihh.ie/index.cfm/houses/house/name/Woodbrook

[4] Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[5] http://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2013/05/house-of-blacker.html

These Section 482 listings are open on certain dates in March 2025, so you might still have time for a visit! I have separated below the places that are listed as Accommodation.

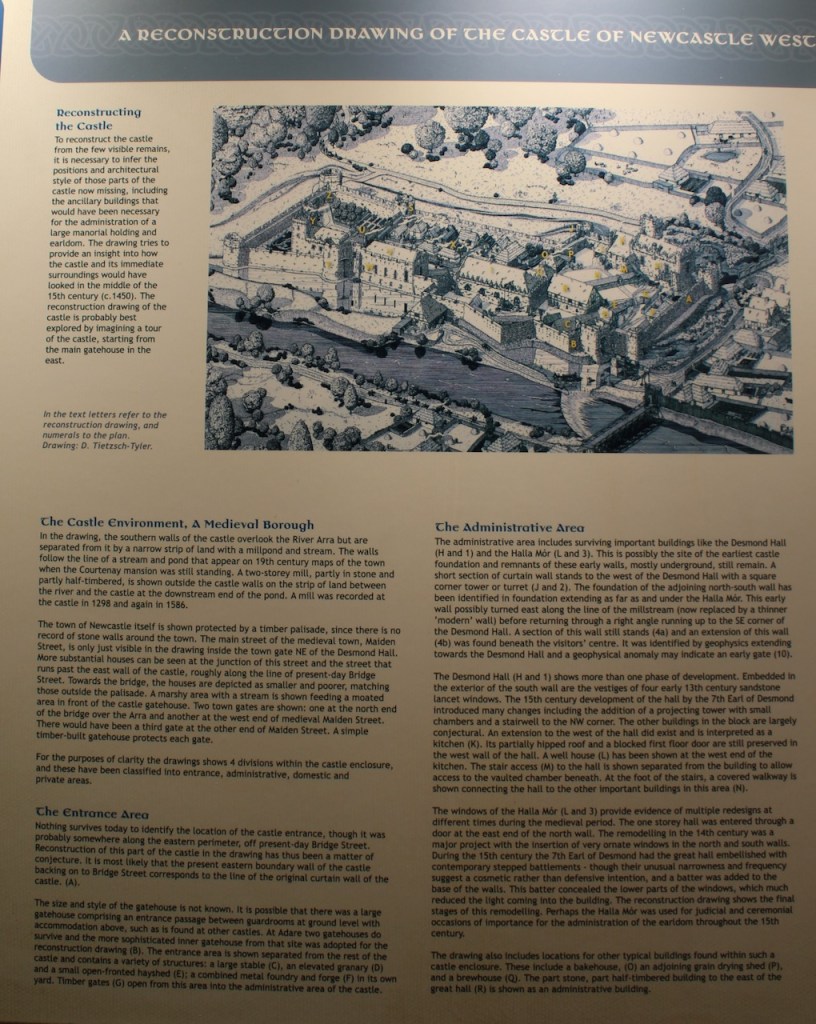

Huntington Castle, Clonegal, Co. Carlow, Y21 K237

Postal address: Huntington Castle, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford

Open: Feb 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, 22-23, Mar 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, 22-23, 29-30, Apr 5-6, 12-30, May 1-31, June 1-30, July 1-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1-30, Oct 4-5, 11-12, 18-19, 25-31, Nov 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, 22-23, 29-30, Dec 6-7, 13-14, 20-21, 11am-5pm

Fee: house/garden, adult €13.95, garden €6.95, OAP/student, house/garden €12.50, garden €6, child, house/garden €6.50, garden €3.50, group and family discounts available

Corravahan House & Gardens, Corravahan, Drung, Ballyhaise, Co. Cavan, H12 D860

Open: Jan 3-4, 10-11, 17-18, 24-25, 31, Feb 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 28, Mar 1, 7-8, 14, May 8-11, 15-18, 22-25, June 12-15, 19-22, 26-29, Aug 8-10, 15-24, 29-31, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student/child €5

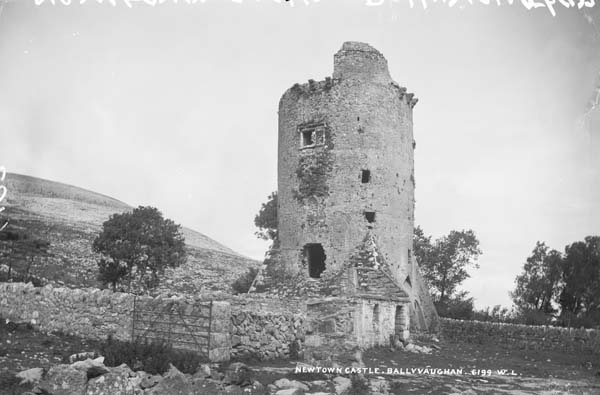

Newtown Castle, Newtown, Ballyvaughan, Co. Clare

Open: Jan 6-Dec 19 Mon-Fri, National Heritage Week 16-24, 10am-5pm

Fee: Free

Ashton Grove, Ballingohig, Knockraha, Co. Cork

Open: Jan 7-10, 14-17, 21-24, Feb 10-14, 18, 25, Mar 4, May 1-5, 8-11, 13, 15-16, 20, 22-23, June 3-8, 10-15, 17-20, Aug 16-24, 8am-12 noon

Fee: adult €6, child €3, student/OAP free

Blarney Castle & Rock Close, Blarney, Co. Cork

Open: all year, Jan-Mar, Nov, Dec, 9am-5pm, Apr, Oct, 9am-5.30pm, May- Sept 9am-6pm,

Fee: adult €23, OAP/student €18, child €11

Kilshannig House, Rathcormac, Co. Cork, P61 AW77

Open: March 18-19, 21, 24, 26-27, April 2, 4-7, 9, 11-13, 21, 23, 25, May 12, 14, 16-17, 19, 21, 23-26, 28, 30, June 2, 4, 6-9, 11, 13, 16, 25, 27-29, July 2, 4-7, 14, 16, 18-20, 28, 30, Aug 1- 4, 6, 8, 11, 13, 15-25, Sept 18, 20, 22-25, 27, 29, 8.30am-3pm,

Fee: adult €14, OAP €12, student €10, child €8

Woodford Bourne Warehouse, Sheares Street, Cork

www.woodfordbournewarehouse.com

Open: all year, except Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, 12 noon-10pm

Fee: Free

Bewley’s, 78-79 Grafton Street/234 Johnson’s Court, Dublin 2

Open: all year, except Christmas Day, Jan- Nov, 8am-6.30pm, Dec 8am-8pm

Fee: Free

Doheny & Nesbitt, 4/5 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin 2

Open: all year, except Christmas Day, Mon-Wed, 9am-12 midnight, Thurs-Sat, 9am-1.30am, Sun, 9am-12 midnight

Fee: Free

Hibernian/National Irish Bank, 23-27 College Green, Dublin 2

Open: all year, except Jan1, and Dec 25, 9am-8pm

Fee: Free

The Odeon (formerly the Old Harcourt Street Railway Station), 57 Harcourt Street, Dublin 2

Open: all year Tue-Sat, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24, 12 noon-12 midnight

Fee: Free

Powerscourt Townhouse Centre, 59 South William Street, Dublin 2

Open: all year, except New Year’s Day, Christmas Day, 10am-6pm

Fee: Free

10 South Frederick Street, Dublin 2, DO2 YT54

Open: all year, 2pm-6pm

Fee: Free

The Church, Junction of Mary’s Street/Jervis Street, Dublin 1

Open: Jan 1-Dec 23, 27-31, 11am-11pm

Fee: Free

Clonskeagh Castle, 80 Whitebeam Road, Clonskeagh, Dublin 14

Open: Jan 5-9, Feb 28, Mar 1-7, 9, May 1-10, June 1-10, July 1-10, Aug 16-25, Nov 4-6, Dec 2-4, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €12, student/OAP/groups €8, groups over 4 people €8 each

Martello Tower, Portrane, Co. Dublin

Open: March 1- Sept 21, Sat & Sun, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €6, student/OAP €2, child free

Tibradden House, Mutton Lane, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16, D16 XV97

Open: Jan 7-17, 24, Feb 3, 10, 17, 24, Mar 3, 10, 21, 24, Apr 4, May 2-3, 9-10, 16-17, 23, 29-30, June 13-15, 19-22, 25-28, Aug 15-24, Sept 3-6, 12-13, 19-20, 26-27, Jan-Apr, May-June, Aug, 2pm-6pm, Feb and Sept, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €8, student/OAP/group €5

Woodville House Dovecote & Walls of Walled Garden, Craughwell, Co. Galway

Open: Feb 1-3, 7-10, 14-17, 21-24, 28, Mar 1-3, 7-10, 14-17, Apr 18-21, May 16-19, June 1-2, 6-9, 13-16, 20-23, 27-30, Aug 1-4, 8-11, 15-25, Feb-May, 12 noon-4pm, June and August, 11am-5pm, last entry 4.30pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP €9, student, €6, child €4 must be accompanied by adult, family €25 (2 adults and 2 children)

Derreen Gardens, Lauragh, Tuosist, Kenmare, Co. Kerry

Open: all year, 10am-6pm

Fee: adult/OAP/student €10, child €5, family ticket €30 (2 adults & all accompanying children under18) 20% discount for groups over 10 people

Kells Bay House & Garden, Kells, Caherciveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48

Open: Jan 1-4, Feb 1-Dec 21, 27-31, Jan-Apr, Oct-Dec 9am-5pm, May-Sept 9am-6pm

Fee: adult €9.50, child €7.50, family €30 (2 adults and up to 3 children 17 years or under) concessions 10% on groups up to 20 persons

Farmersvale House, Badgerhill, Kill, Co. Kildare, W91 PP99

Open: Jan 6-21, Mar 3-6, July 18-31, Aug 1-26, 9.30am-1.30pm

Fee: adult €5, student/child/OAP €3, (Irish Georgian Society members free)

Harristown House, Brannockstown, Co. Kildare, W91 E710

Open: Feb 3-7, 24-28, Mar 10-14, 17-21, May 1-14, July 23-25, 28-31, Aug 1, 5-24, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €15, OAP/student/child €10

Leixlip Castle, Leixlip, Co. Kildare, W23 N8X6

Open: Feb 17-21, 24-28, Mar 3-7, 10-14, May 12-23, June 9-20, Aug 16-24, Sept 1-7, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student/child €4, no charge for local school visits/tours

Kilkenny Design Centre, Castle Yard, Kilkenny

Open: Jan 1 new year’s day 12 noon-5.30pm, Jan 2-Dec 23, 27-31, Jan, Feb, Mar, Apr, Oct, Nov, Dec, Sun, 11am-6pm, Mon-Sat, 10am-6pm, May, 10am-6pm, June, July, Aug, Sept, Sun, 10am-6pm, Mon- Sat, 9am-6pm,

Fee: Free

Ballaghmore Castle, Borris in Ossory, Co. Laois

Open: all year, except Christmas Day, 11am-5pm

Fee: adult €15 with Guide, child over 7 years /OAP/student €8, family of 4 €30

Manorhamilton Castle (Ruin), Castle St, Manorhamilton, Co. Leitrim

Open: Jan 3, 6, 10, 13, 17, 20, 24, 27, 31, Feb 3, 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, 24, 28, Mar 3, 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, 24, 28, 31, Apr 4, 7, 11, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28, May 2-5, 9-12, 16-19, 23, 26, 30, June 2, 6, 9, 13, 16, 20, 23, 27, July 4, 7, 11, 14, 18, 21, 25, Aug 1, 4, 8, 15-25, 29, Sept 1, 5, 8, 12, 15, 19, 22, 26, 29, 10am-4pm

Fee: adult €5, child/OAP/student free

Brookhill House, Brookhill, Claremorris, Co. Mayo

Open: Mar 13-26, Apr 17-25, June 12-26, July 8-24, Aug 15-26, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student €4, National Heritage Week free

Beau Parc House, Beau Parc, Navan, Co. Meath, C15 D2K6

Open: Mar 1-20, May 1-31, Aug 16-24, 10am-2 pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/student/child €8

St. Mary’s Abbey, High Street, Trim, Co. Meath

Open: Feb 8-14, 24-28, Mar 3-7, 26-28, May 10-18, June 23-30, July 21-27, Aug 16-24, Sept 14-20, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €5, OAP/student/child €2

Swainstown House, Kilmessan, Co. Meath, C15 Y60F

Open: Mar 4-5, 7-8, April 7-8, 10-11, May 5-11, June 2-8, July 7-13, Aug 16-24, Sept 8-12, 15-19, Oct 6-7, 9-10, Nov 3-4, 6-7, Dec 1-2, 4-5, 11am-3pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student/child €5, National Heritage Week free

Crotty Church, Castle Street, Birr, Co. Offaly

Open: Jan 1- Dec 31, Mon-Fri, excluding Bank Holidays, National Heritage Week Aug 16-24, 12 noon-5pm

Fee: Free

Springfield House, Mount Lucas, Daingean, Tullamore, Co. Offaly, R35 NF89

Open: Feb 1-3, 22-23, Mar 8-9, 15-17, Apr 5-6, May 3-5,10-11, 17-18, July 5-6, 26-30, Aug 1-24, Sept 29-30, Oct 1-5, 25-27, 2pm-6pm

Fee: Free

Strokestown Park House, Strokestown, Co. Roscommon

www.strokestownpark.ie www.irishheritagetrust.ie

Open: Jan 10-Dec 24, Jan-Feb, Nov-Dec 10.30am-4pm, Mar-May, Sept-Oct, 10am-5pm, June-Aug, 10am-6pm

Fee: adult house €14.50, tour of house €18.50, child €7, tour of house €10, OAP/student €12, tour of house €14.50, family €31, tour of house €39

Beechwood House, Ballbrunoge, Cullen, Co. Tipperary, E34 HK00

Open: Feb 25-27, Mar 4-6, 11-13, April 1-11, May 8-11, 15-18, 22-25, June 7-8, 14-15, Aug 16-24, Sept 2-4, 9-11, 16-18, 23-28, 9.15am-1.15pm

Fee: adult €5, OAP/student €2, child free, fees donated to charity

Clashleigh House, Clogheen, Co. Tipperary

Open: Mar 4, 6, 11, 13, 18, 20, 25, 27, Apr 1, 3, 8, 10, 15, 17, 22, 24, 30, May 6, 8, 10-11, 13, 15, 17-18, 20, 22, 24-25, 27, 29, June 3, 5, 10, 12, 17, 19, 24, 26, Aug 16-24, Sept 2, 4, 9, 11, 16, 18, 23, 25, 30, Oct 2, 7, 9, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student/child €4

Fancroft Mill , Fancroft, Roscrea, Co. Tipperary

Open: Feb 3-15, Mar 24-30, May 13-28, June 10-20, Aug 15-27, 10am-2pm

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student €6, child free under 5 years, one to one adult supervision essential, group rates available

Cappoquin House & Gardens, Cappoquin, Co. Waterford, P51 D324

www.cappoquinhouseandgardens.com

Open: Apr 7-12, 15-19, 22-26, 28-30, May 1-3, 5-10, 2-17, 19-24, 26-31, June 2-7, Aug 16-24, 9am-1pm

Gardens open all year

Fee: adult house €10, house and garden €15, garden only €6, child free

The Presentation Convent, Waterford Healthpark, Slievekeel Road, Waterford City

Open: Jan 2- Dec 23, 29-30, Mon-Fri, National Heritage Week Aug 16-24, closed Bank Holidays, 8.30am-5.30pm

Fee: Free

Lough Park House, Castlepollard, Co. Westmeath

Open: Mar 15-21, 28-31, Apr 18-21, May 1-7, June 1-9, July 12-25, Aug 1-7, 16-24, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €6

Tullynally Castle & Gardens, Castlepollard, Co. Westmeath, N91 HV58

Open: Castle, May 1-3, 8-10, 15-17, 22-24, 29-31, June 5-7, 12-14, 19-21, 26-28, July 3-5, 10-12, 17-19, Aug 1-2, 7-9, 14-24, 28-30, Sept 4-6, 11-13, 18-20, 11am-3pm

Garden, Mar 27-Sept 28, Thurs-Sundays, and Bank Holidays, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24,11am-5pm

Fee: castle adult €16.50, child entry allowed for over 8 years €8.50, garden, adult €8.50, child €4, family ticket (2 adults + 2 children) €23, adult season ticket €56, family season ticket €70, special needs visitor with support carer €4, child 5 years or under is free

Kilcarbry Mill Engine House, Sweetfarm, Enniscorthy, Co Wexford

Open: Jan 1-4, 29-31, Feb 3-5, Mar 5-7, 10-11, Apr 3-4, 11-13, May 10-12, 19-23, July 5-7, Aug 2-31, Dec 19-23, 27-30, 12 noon-4pm

Fee: adult €10, student/OAP €5, child free

Sigginstown Castle, Sigginstown, Tacumshane, Co. Wexford, Y35 XK7D

Open: Mar 14-17, 21-23, April 4-6, 11-13, 18-21, May 2-5, 9-11, 16-18, 23-25, June 6-8, 13-15, 20-22, 27-29, July 4-6, 11-13, 18-20, 25-27, Aug 1-4, 8-10, 15-24, Sept 6-7, 13-14, 20-21, 27-28, 1pm-5pm

Fee: adult €10, child/OAP/student €8, groups of 6 or more €8 per person

Altidore Castle, Kilpeddar, Greystones, Co. Wicklow, A63 X227

Open: Mar 10-30, May 1-31, June 1-5, 1pm-5pm, Aug 16-24, 2pm-6pm

Fee: adult €10, OAP/child/student €8

Castle Howard, Avoca, Co. Wicklow

Open: Jan 6-8, Feb 10-14, Mar 3-5, 18-20, June 4-7, 9-11, 23-28, July 7-12, 21-24, Aug 16-24, Sept 1-6, 13, 20, 28-30, Oct 1, 6-8, 9am-1pm

Fee: adult €8.50, OAP/student €6.50, child €5

Mount Usher Gardens, Ashford, Co. Wicklow, A67 VW22

Open: all year, except Christmas Day and St. Stephen’s Day, Jan-Mar, Nov-Dec, 10am-5pm, Apr-Oct, 10am-5.30pm

Fee: adult €10, student/OAP €8, child over 4 years €5, under 4 years free, group rate (10 or more people) €8 per person

Powerscourt House & Gardens, Powerscourt Estate, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, A98 W0D0

Open: Jan 1-Dec 24, 27-31, house and garden, 9.30am-5.30pm, ballroom and garden rooms, 9.30am-1.30pm

Fee: Jan-Oct, adult €14, OAP, €12, student €10.50, child €5.50, family €20, Nov- Dec, adult €10.50, OAP €9.50, student €9, child €5.50, Jan- Oct, concessions-family ticket 2 adults and 3 children under 18 years €33, concession-Nov-Dec family 2 adults and 3 children under 18 €25

Russborough, The Albert Beit Foundation, Blessington, Co. Wicklow, W91 W284

Open: Feb 1-Dec 23, 27-31, Feb, Nov, Dec 9am-5.30pm, Mar-Oct 9am-6pm Fee: adult €14.

Accommodation:

Cabra Castle (Hotel), Kingscourt, Co. Cavan, A82 EC64

Open: all year, except Dec 24, 25, 26, 11am-4pm

Fee: Free

Claregalway Castle, Claregalway, Co. Galway, H91 E9T3

Tourist Accommodation Facility

Open: January 2- December 24

Ballyseede Castle, Ballyseede, Tralee, Co. Kerry

Open: Mar 14-Dec 31, 8am-12 midnight

Fee: Free

Owenmore, Garranard, Ballina, Co. Mayo

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year except Jan, Feb, June 15- July 10, Dec

Cillghrian Glebe now known as Boyne House Slane, Chapel Street, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 P657

(Tourists Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24, 9am-1pm

Fee: Free

Loughcrew House, Loughcrew, Old Castle, Co. Meath

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year

Fee: adult €8, OAP/student €6, child €4, carers free

Slane Castle, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 XP83

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: January, February, May, June, July, August, (Mar-Apr, Sept-Dec, Mon-Thurs)

Fee: adult €14, OAP/student €12.50, child €8.40 under 5 years free

Tankardstown House, Rathkenny, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 D535

Open: all year, National Heritage Week, Aug 16-24, 9am-1pm

Fee: Free

Castle Leslie, Glaslough, Co. Monaghan

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year, National Heritage Week events August 16-24

Fee: Free

The Maltings, Castle Street, Birr, Co. Offaly

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year

Lismacue House, Bansha, Co. Tipperary

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: Mar 1-Oct 31

Wilton Castle, Bree, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, Y21 V9P9

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

Open: all year

Woodbrook House, Killanne, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, Y21 TP 92

(Tourist Accommodation Facility)

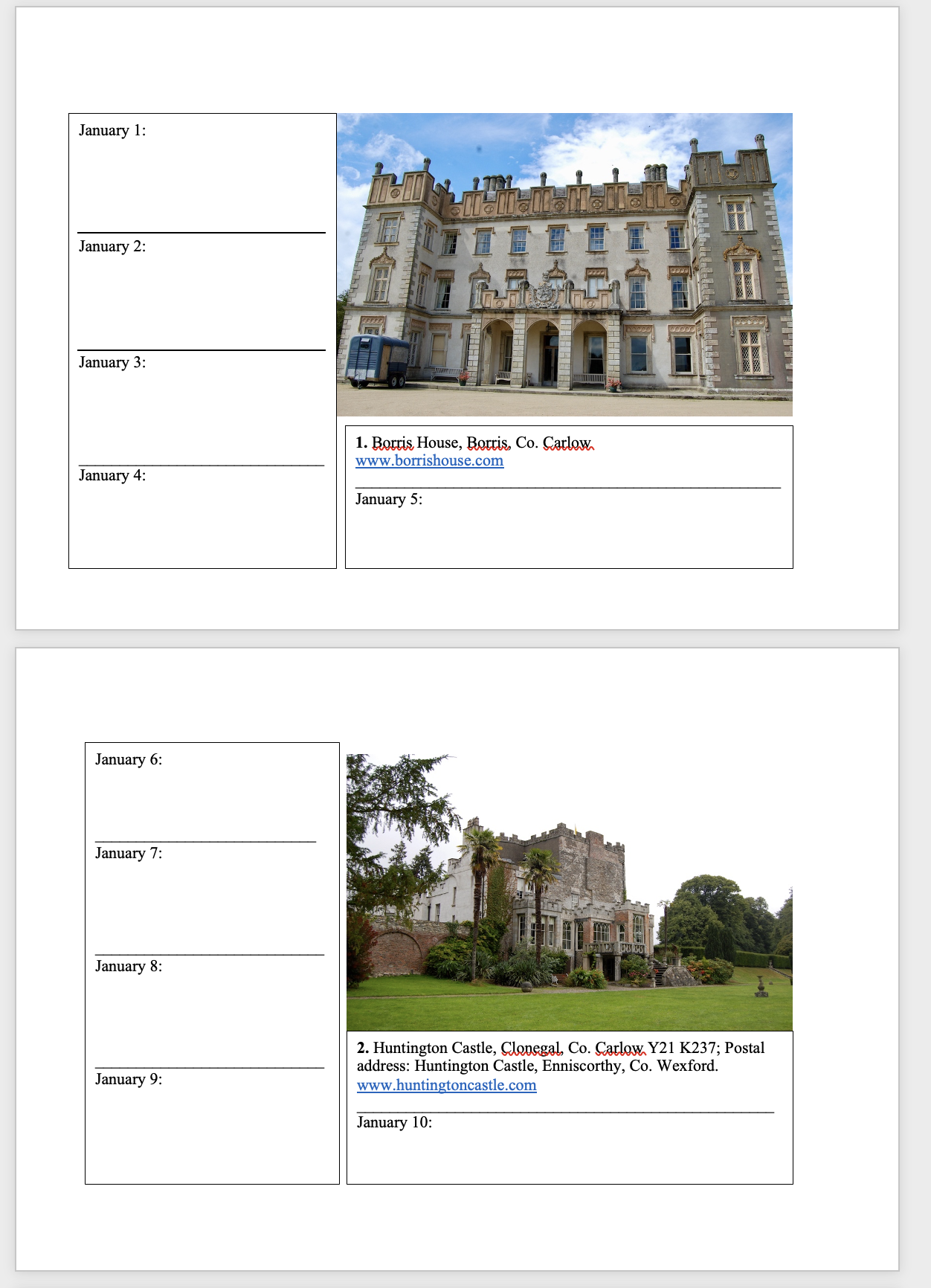

Open: all year