Sorry I published and sent an entry of my notes about Dunroe Lodge, County Carlow. I’m compiling a database on big houses for myself and I published that entry by mistake. I also published an entry last week by mistake. It’s very unprofessional of me – sorry for sending you random unsuitable posts!

Author: jenjunebug

Crotty Church, Birr, County Offaly – section 482

Open dates in 2026: Jan 1- Dec 31, Mon-Fri, excluding Bank Holidays, 12 noon-5pm

Fee: Free [caution: when we visited during Heritage Week 2024, it was not open]

Stephen and I visited Crotty Church in Birr during Heritage Week in 2024.

However, the building was not open, and I suspect it never is, as it has been converted to apartments. Instead, we sat outside the building despite rain threatening, and listened to a talk organised by Aoife Crotty about the Crotty Schism (1820-1850) which was led by Father Michael Crotty (1795-1862). Disgusted at not having access to the building despite its Section 482 designation, I didn’t ask Aoife whether she is related to Father Michael Crotty! The speaker who gave the rather rambling talk did not introduce himself so I did not identify who he is, and I suspect he is an owner of the building. The Inventory tells us that the building was built in 1839. The Schism itself began in 1826.

The Inventory describes the former church: “Hipped slate roof with terracotta ridge tiles and cast-iron rainwater goods. Ashlar limestone to façade with tooled stone quoins, roughcast render to sides and rear elevations. Pointed-arched window openings to façade with tooled stone surrounds and sills with timber casement windows. Square-headed openings to sides and rear elevations with stone sills and timber casement windows. Tudor arched door opening with chamfered stone reveals, timber battened door, surmounted by fanlight. Side and rear site bounded by random coursed stone wall.“

Although the building was built for a Catholic congregation originally, the followers of Michael Crotty, it is identified in the National Inventory as a Presbyterian former church. [1] The talk’s presenters were unable to tell us much about the history of the building.

There are a few graves outside the church, which seemed oddly random, and the talk’s organisers were unable to tell us about them. It looks like there may be gravestones but perhaps the burials did not actually take place on the grounds of the church.

Crotty began his position as a Catholic priest in Birr in 1821. With an increasing Catholic population, the congregation needed a new church.

He began his training to be a Catholic priest in Maynooth University but left, and finished his training in France. He obtained a position in Birr, but he became increasingly radical and he and his cousin, William Crotty (1808–56), also a Catholic priest, favoured Protestant rather than Catholic beliefs. They sought to set up a new church in a new building, and took many of their congregation with them. Lord Rosse of Birr Castle contributed toward the building fund, which was set up in 1808. Crotty fell out with the Building Committee and the Parish Priest, and in 1825 he was moved to Shinrone. However, in 1826 he was back in Birr causing trouble, arguing with the parish priest and attempting to take over the Catholic church building, staging a “sit in.” The new church still had not been built. It took the 66th Regiment of the army under Lord Rosse to evict Crotty and his followers!

Next Crotty rented a house where he held services. The building we visited was not the only one that the congregation occupied. One of the organisers of the talk pointed out another building across the road, an old warehouse, where Crotty also preached. This too is being converted to apartments.

The same owner owns The Maltings, also a Section 482 property, which is meant to offer tourist accommodation and therefore does not need to open to the public. However, any time I have tried to book this accommodation, several times over the years since 2019, the building is not actually offering tourist accommodation.

The organisers of the talk gave us a booklet about the Crotty Schism, written by Reverend Edward Whyte. Michael Crotty was increasingly erratic and eventually ended up in an asylum for the mentally ill in Belgium. William became a Presbyterian minister in Birr.

You can read more about the Schism in an article on the Offaly History Blog by Ciaran McCabe. [2]

Yeomanstown Corn Mill, Naas, Co. Kildare, W91AFH1 for sale courtesy Lisney Sotheby’s

For sale October 2024, €1,650,000, courtesy Lisney Sotheby’s, 5 bedroom, 4 bath 641m2

Every once in a while a property is offered for sale which I think could become a Section 482 property. I can’t resist sharing this one, which is a joy. I have still to write of the other mill house, Millbrook, which we visited this year, and I have yet to visit Kilcarbry in Wexford, another corn mill, and Fancroft Mill in Tipperary.

The advertisement reads: “An attractive and exquisite residence sympathetically set within the fabric of an historic corn mill and magically situated within private grounds, which extend to the banks of the river Liffey and include the original cascading mill race canal. In all about 3 acres or 1.2 hectares and some 6,900 square feet or 641 square metres of accommodation.”

The ad tells us: “Historically and architecturally significant Yeomanstown Corn Mill has a rare magical quality and retaining much of the original industrial mill equipment makes a truly unique and enchanting residence. Milling activity on the grounds of Yeomanstown Corn Mill is thought to date back to the 14th-century. The current mill is largely late Georgian, circa 1810, in composition but likely incorporates earlier structures. A mill illustrated on maps back to 1654 in the mid-17th-century.“

The ad continues: “With the resplendent red brick exterior stretching up to four and five floors and abutting the cascading mill wheel canal Yeomanstown Corn Mill is enchanting and extremely picturesque. The restoration and conversion of the building into a home magically marries the rare original industrial charm with contemporary living requirements, to create an utterly enticing and fun home. The unashamedly industrial themed interior incorporates well thought out living spaces punctuated with original millstones, corn elevator shafts, massive ceiling beams, rustic timber staircases and ladders, white washed walls and varying ceiling heights to alluring effect.“

I love all the wood inside and the beautiful stone flooring.

“A flagged stone reception hall retains the original corn milling wheels behind a glass wall and features the rustic mill staircase to the upper floors and leads to a study, an office, a spacious bathroom with a large bath, a shower and a sauna and two bedrooms, one with a hobbit like door to an enclosed walled garden.“

“The first floor has a large open plan kitchen with a fully fitted kitchen, large breakfast counter worktop, industrial themed lighting and incorporating original mill fittings and equipment to great effect. It leads to a fine living room with a large cast iron stove and used as a dining and television space, off the kitchen there is a large pantry.“

“The second floor has an incredible double height studio space with an evocative mix of tall white washed walls and exposed timber beams and boards and, again, incorporating original mill components. A large cast iron stove ample warms the space and there are two stairs to an upper mezzanine library floor. Itself opening onto the third-floor landing, which leads to the marvellously generous master bedroom suite with a large bedroom and interconnecting shower room and dressing room. There are two further bedrooms (on the second floor) one with a shower room ensuite and the other served by a second shower room on the landing hall. The final fifth or attic floor was previously utilised as an art studio space and is currently used as a gym and store.“

“Bounding the river Liffey and including a fine riverbank stretch, one part opening into a natural river swimming hole or pool, the gardens are well-timbered and private. A striking cut-stone aqueduct bridge, Victoria Bridge, dates to 1837 and forms a great folly backdrop to the gardens. An original wrought iron bridge beside the impressive and large timber mill wheel leads to the gardens, abundant with wildlife and having an island like feel, being bounded by the canal and river. Although usefully also be accessed by vehicular gate. The mill wheel is thought capable of generating 3kw of electricity per hour, or more, in a recent appraisal.“

I always think we should use water power again! I thought years ago I read that a hotel on Charlemount Street was going to tap into the Poddle below to generate electricity, but I never heard more about it – let me know if you know about it!

“Yeomanstown is a highly fashionable area and links easily to Dublin city and airport. The nearby village of Caragh is quaint and includes a school, petrol station, grocery store, take-away restaurants and a hair salon. Naas town is just 7.7miles miles or 12.3km away and has a hospital and array of shopping, pubs, eateries and restaurants. Sallins village, just a 12 minutes drive away, provides train access with extensive commuter services into Dublin city.“

Forgive me for once again not publishing about a Section 482 property – I am on a prolonged hiatus, as we were so busy trying to buy ourselves a small country hideaway for writing and growing fruit and vegetables. We are finally nearly completed the process, I think! Unfortunately we can’t buy something like this, an absolute dream home, but I’m delighted with what we have found.

Emo Court, County Laois – Office of Public Works

Emo Court, County Laois:

General enquiries: 057 862 6573, emocourt@opw.ie

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/:

“Emo Court is a quintessential neo-classical mansion, set in the midst of the ancient Slieve Bloom Mountains. The famous architect James Gandon, fresh from his work on the Custom House and the Four Courts in Dublin, set to work on Emo Court in 1790. However, the building that stands now was not completed until some 70 years later [with work by Lewis Vulliamy, a fashionable London architect, who had worked on the Dorchester Hotel in London and Arthur & John Williamson, from Dublin, and later, William Caldbeck].

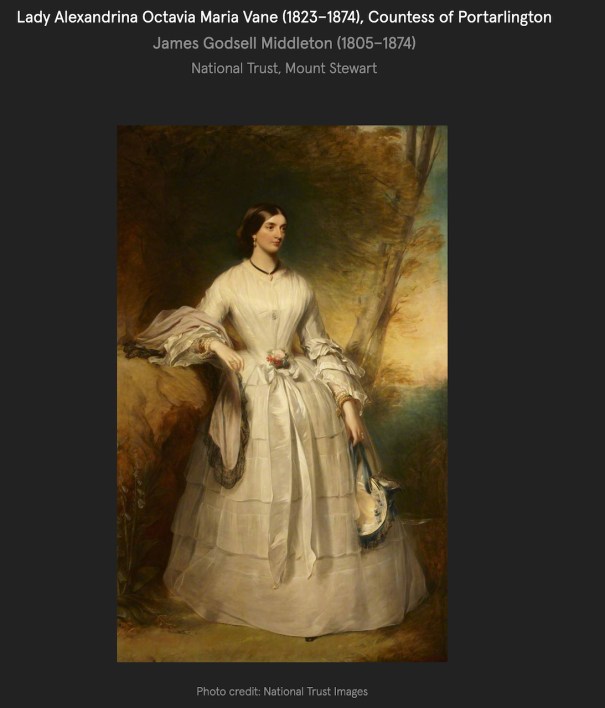

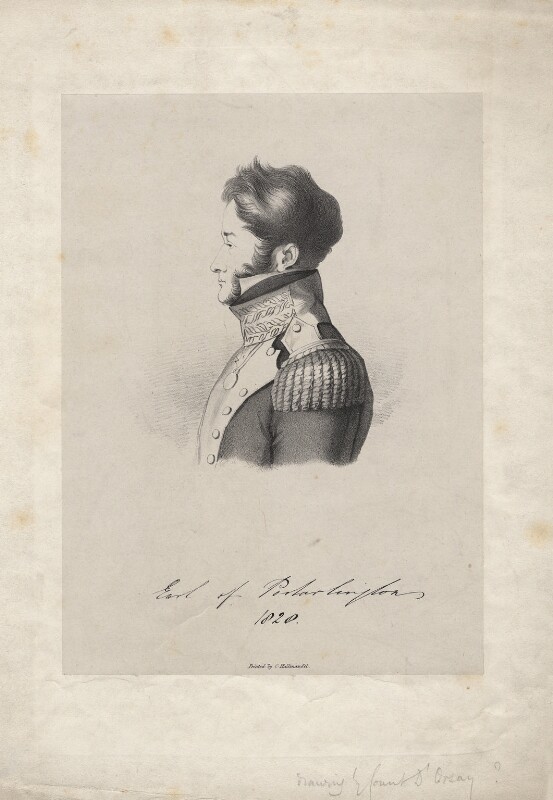

“The estate was home to the earls of Portarlington until the War of Independence forced them to abandon Ireland for good. The Jesuits moved in some years later [1920] and, as the Novitiate of the Irish Province, the mansion played host to some 500 of the order’s trainees.

“Major Cholmeley-Harrison took over Emo Court in the 1960s and fully restored it [to designs by Sir Albert Richardson]. He opened the beautiful gardens and parkland to the public before finally presenting the entire estate to the people of Ireland in 1994.

“You can now enjoy a tour of the house before relaxing in its charming tearoom. The gardens are a model of neo-classical landscape design, with formal lawns, a lake and woodland walks just waiting to be explored.” [2]

We visited Emo during Heritage Week 2024 as some rooms were open to the public – finally! Despite the episode on television several years ago of “Great Irish Interiors” where the house was prepared to be open to the public, it is still not open to the public. And it is still not. Just a few rooms were open for Heritage Week. Major Cholmeley-Harrison will be tearing his hair out, if he has any left, in his grave – imagine giving the house to the state, and the state accepts it and then closes it for thirty years!

It was so exciting to go inside. My great uncle Father Tony Baggot was a novitiate there when the Jesuits owned the property.

Unfortunately I was not allowed to take photographs. I was not impressed by the reason given: it’s not finished yet. For goodness sake, who do the OPW think owns the house? We do! Apparently they had left it arranged as when owned Major Cholmeley-Harrison, opened it for a short while, and now they are removing traces of him from several areas. Poor Mr. Cholmeley-Harrison.

Mark Bence-Jones tells us that the 1st Earl of Portarlington was interested in architecture and was instrumental in bringing James Gandon to Ireland, in order to build the new Custom House. The name Emo is an Italianised version of the original Irish name of the estate, Imoe. [3]

The Emo Court website tells us of the history:

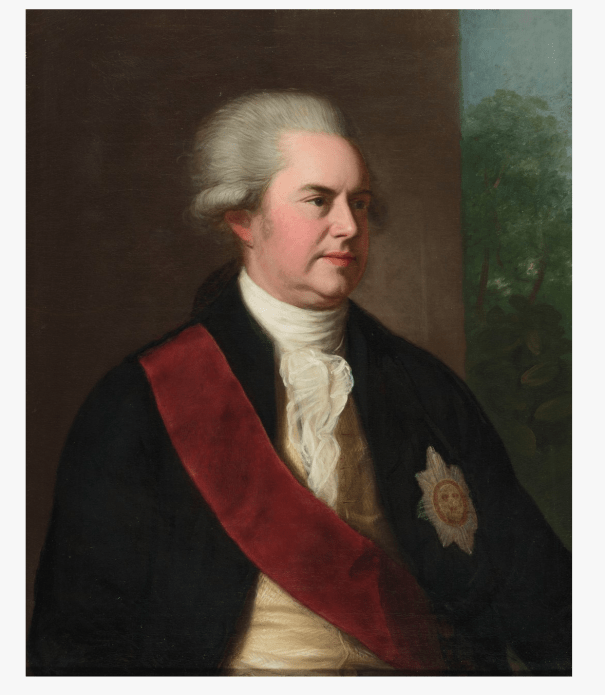

“John Dawson, 1st Earl of Portarlington [1744-1798] commissioned the building of Emo Court in 1790 although the house was not finally completed until 1870, eighty years later. Emo Court is one of only a few private country houses designed by the architect James Gandon. Others were Abbeyville, north Co. Dublin for Sir James Beresford [or is it John Beresford (1738-1805)? later famous for being the home of politician Charles Haughey] and Sandymount Park, Dublin for William Ashford. In addition, Gandon built himself a house at Canonbrook, Lucan, Co. Dublin.” [4]

Many of Gandon’s original drawings, plus those of his successors, are in the Irish Architectural Archive, 45 Merrion Square, Dublin. [5] The Emo Court website continues:

“James Gandon was born in London of Huguenot descent. He studied classics, mathematics and drawing, attending evening classes at Shipley’s Academy in London. At the age of fifteen, James was apprenticed to the architect Sir William Chambers and about eight years later, set up in business on his own. His first connection with Ireland was in 1769 when he won the second prize of £60 in a competition to design the Royal Exchange in Dublin, now the City Hall. He was invited to build in St Petersburg, Russia, by Princess Dashkov, and offered an official post with military rank. However, he chose instead to accept an offer from Sir John Beresford and John Dawson, Lord Carlow, later 1st Earl of Portarlington, to come to Dublin to build a new Custom House. This was begun in 1781. The following year, Gandon was commissioned to make extensions to the Parliament House, originally designed by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce. Here he added a Corinthian portico as entrance to the Lords’ Chamber. After the Act of Union in 1801, the building became the Bank of Ireland. In 1785, Gandon was commissioned to design the new Four Courts. The third of his great Dublin buildings was the King’s Inns, begun in 1795. His few private houses were designed for patrons and friends.” [see 4]

The website continues: “In the early 18th century, Ephraim Dawson [1683-1746], a wealthy banker, after whom Dawson Street in Dublin is named, purchased the land of the Emo Estate and other estates in the Queen’s County (Co. Laois). He married Anne Preston, heiress to the Emo Park Estate and fixed his residence in a house known as Dawson Court, which was in close proximity to the present Emo Court. His grandson, John Dawson, was created 1st Earl of Portarlington in 1785. Three years later, he married Lady Caroline Stuart, daughter of the [3rd] Earl of Bute, who was later Prime Minister of England. John Dawson commissioned Gandon to design Emo Court in 1790.“

Stephen’s ancestor Earl George Macartney married another daughter of the 3rd Earl of Bute! Their mother was the wonderful Lady Mary Wortley-Montague whose husband was a diplomat and she wrote memoires of their travels. She even visited a harem.

“After Gandon died in 1823, to be buried in Drumcondra churchyard, the 2nd Earl of Portarlington, also John Dawson, engaged Lewis Vulliamy, a fashionable London architect, who had worked on the Dorchester Hotel in London and A. & J. Williamson, Dublin architects, to finish the house. In the period, 1824-36, the dining room and garden front portico with giant Ionic columns were built, but on the death of the 2nd Earl in 1845, the house still remained unfinished. It was not until 1860 that the 3rd Earl, Henry Ruben John Dawson [or Dawson-Damer, the son of the 2nd Earl’s brother Henry Dawson-Damer, who had the name Damer added to his name after the family of his grandmother, Mary Damer, who married William Henry Dawson, 1st Viscount Carlow] commissioned William Caldbeck, a Dublin architect, and Thomas Connolly, his contractor, to finish the double height rotunda, drawing room and library.” [see 4] Caldbeck also added a detached bachelor wing, joined to the main block by a curving corridor.

Although it was not built during Gandon’s time, most of the house is as it was designed by Gandon, with some additions or changes. Mark Bence-Jones describes the house:

“Of two storeys over a basement, the sides of the house being surmounted by attics so as to form end towers or pavilions on each of the two principal fronts. The entrance front has seven bay centre with a giant pedimented Ionic portico; the end pavilions being of a single storey, with a pedimented window in an arched recess, behind a blind attic with a panel containing a Coade stone relief of putti; on one side representing the Arts, on the other, a pastoral scene. The roof parapet in the centre, on either side of the portico, is balustraded. The side elevation, which is of three storeys including the attic, is of one bay on either side of a curved central bow.” [see 3]

Bence-Jones continues: “The house was not completed when the 1st Earl died on campaign during 1798 rebellion; 2nd Earl, who was very short of money, did not do any more to it until 1834-36, when he employed the fashionable English architect, Lewis Vulliamy; who completed the garden front, giving it its portico of four giant Ionic columns with a straight balustraded entablature, and also worked on the interior, being assisted by Dublin architects named Williamson. It was not until ca 1860, in the time of 3rd Earl – after the house had come near to being sold up by the Encumbered Estates Court – that the great rotunda, its copper dome rising from behind the garden front portico and also prominent on the entrance front, was completed; the architect this time being William Caldbeck, of Dublin, who completed the other unfinished parts of the house and added a detached bachelor wing, joined to the main block by a curving corridor.” [see 3]

The website continues: “Emo court remained the seat of the Earls of Portarlington until 1920, when the house and its vast demesne of over 4500 ha, (11,150 acres), was sold to the Irish Land Commission. After the Phoenix Park in Dublin, Emo Court was the largest enclosed estate in Ireland. The house remained empty until 1930 when 150 ha., including the garden, pleasure grounds, woodland and lake were sold to the Society of Jesus for a novitiate. The Jesuits made several structural changes to the building to suit their purposes, including the conversion of the rotunda and library as a chapel. The distinguished Jesuit photographer, Fr Frank Browne lived at Emo Court from 1930-57. [7] A notable novitiate was the Irish author, Benedict Kiely.

“The Jesuits remained at Emo until 1969 and the property was eventually sold to Major Cholmeley Dering Cholmeley-Harrison. He embarked upon a long and enlightened restoration, commissioning the London architectural firm of Sir Albert Richardson & Partners to effect the restoration.

“In 1994, President Mary Robinson officially received Emo Court & Parklands from Major Cholmeley-Harrison on behalf of the Nation.” [see 4]

Unfortunately Emo Park house has been closed to the public for renovation for several years, and was closed on the day we visited in July 2021. I am looking forward to seeing the interior, which from photographs and descriptions I have seen, look spectacular. From the outside we gain little appreciation of the splendid copper dome.

In the meantime, you can read more about Emo and see photographs of its interiors on the wonderful blog of the Irish Aesthete Robert O’Byrne. [8]

There are beautiful grounds to explore, however, on a day out at Emo, including picturesquely placed sculptures, an arboretum, lake, and walled garden. Here is a link to a beautiful short film by poet Pat Boran, about the statues at Emo Park, County Laois. https://bit.ly/35uXPO1

[1] p. 336. Tierney, Andrew. The Buildings of Ireland: Central Leinster: Kildare, Laois and Offaly. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2019.

[2] https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/emo-court/

[3] p. 119. Bence-Jones, Mark. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988, Constable and Company Ltd, London.

[4] https://emocourt.ie/history/

For information on Gandon’s house in Lucan, see https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/11201034/canonbrook-house-lucan-newlands-road-lucan-and-pettycanon-lucan-dublin

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2019/02/27/emo-court/

[6] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en/media-assets/media/81101

[7] http://www.fatherbrowne.com

[8] https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/14/of-changes-in-taste/

and https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/02/01/seen-in-the-round/

For photographs of the stuccowork, see https://theirishaesthete.com/2016/03/21/forgotten-virtuosi/

Damer House and Roscrea Castle, County Tipperary, Office of Public Works properties

General information: 0505 21850, roscreaheritage@opw.ie

Finding ourselves with some spare time this Heritage Week (2024) after visiting Emo in County Laois, we drove over to Roscrea, to visit Damer House and Roscrea Castle.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/roscrea-heritage-centre-roscrea-castle-and-damer-house/:

“In the heart of Roscrea in County Tipperary, one of the oldest towns in Ireland, you will find a magnificent stone motte castle dating from the 1280s. It was used as a barracks from 1798, housing 350 soldiers, and later served as a school, a library and even a sanatorium.

“Sharing the castle grounds is Damer House, named for local merchant John Damer [d. 1768], who came into possession of the castle in the eighteenth century. The house is a handsome example of pre-Palladian architecture. It has nine beautiful bay windows. One of the rooms has been furnished in period style.

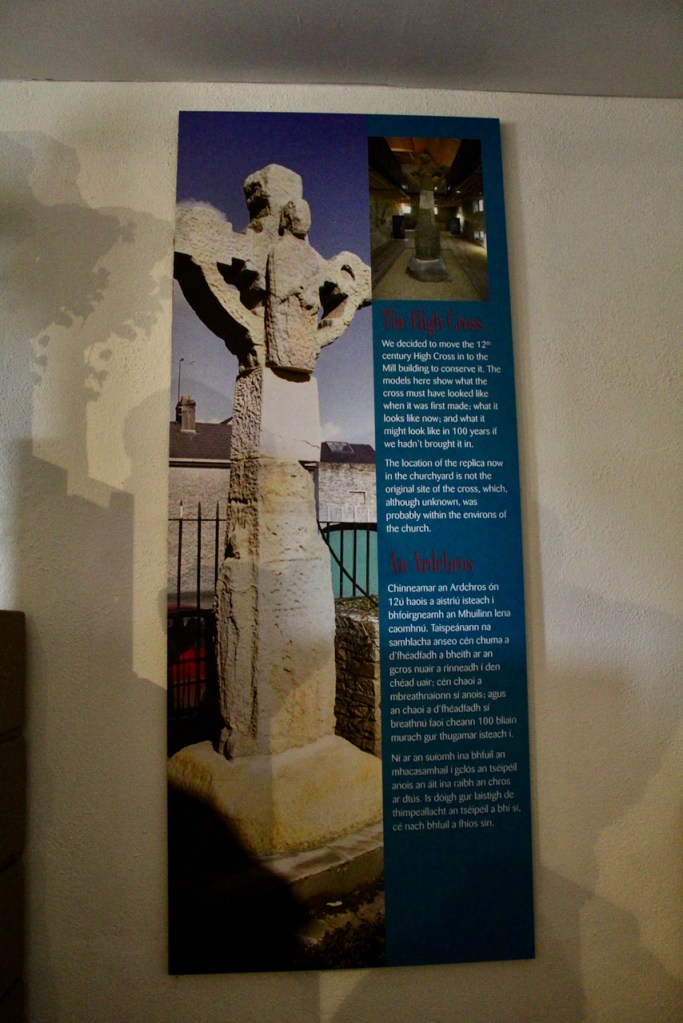

“The grounds also include an impressive garden with a fountain, which makes Roscrea Castle a very pleasant destination for a day out. There is also a restored mill displaying St Crónán’s high cross and pillar stone.“

The castle and Damer house both sit inside bawn walls. Parts of the walls and outbuildings are in good condition, considering their age!

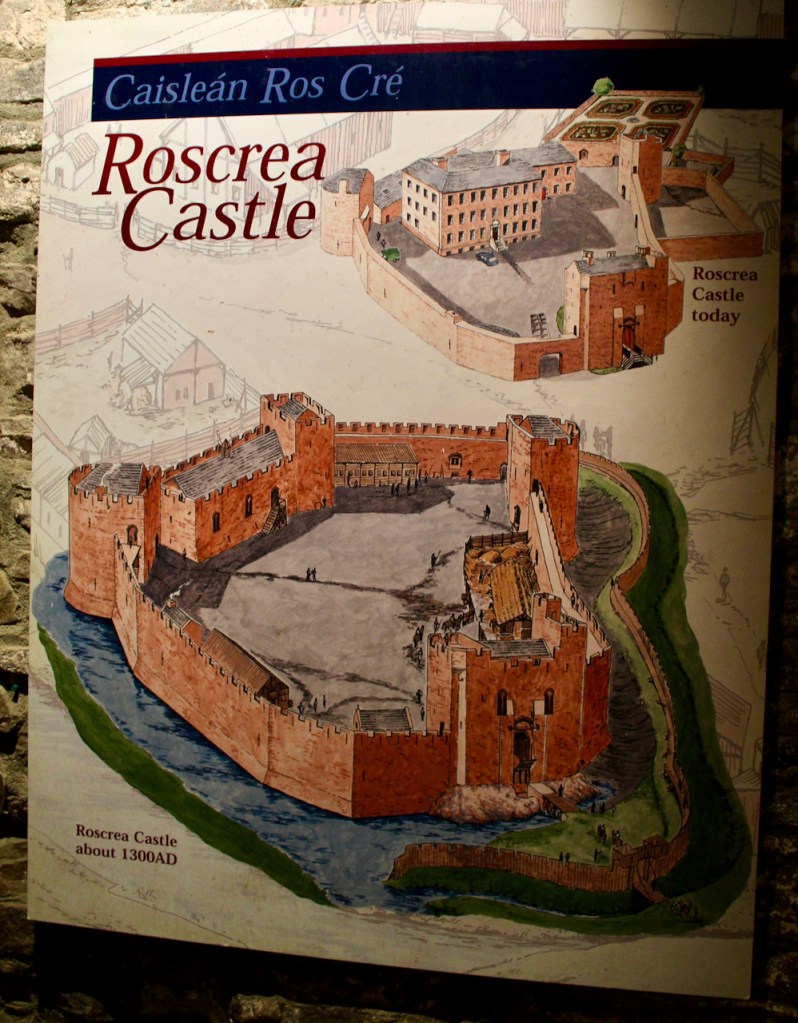

This was originally the site of a motte and bailey fortification known as King John’s Castle. The original wooden castle was destroyed in the late 13th century and was replaced with a stone structure built in 1274-1295 by John de Lydyard. The castle was originally surrounded by a river to the east and a moat on the other sides. [2] It was granted to the Butlers of Ormond in 1315 who held it until the early 18th Century. The castle as we see it today was built from 1332.

Roscrea Castle was sold to the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, by James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormond in 1703. It was bought by the Damers, who built an elegant three-storey nine bay pre-Palladian house in the courtyard in c. 1730.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us:

“The Damer of folklore tradition is a conflation of the first Joseph [c.1630–1720] with his nephew John [1674-1768]. Thus, while Damer built himself a house in County Tipperary in the seventeenth century, the traditional stories about Damer’s Court (or Damerville) relate to a house built by John after his uncle’s death. John’s brother Joseph [1676–1737] built the Damer House in Roscrea, which was saved from demolition in the 1970s and subsequently restored. The Guildhall Library, London, has Damer correspondence among its Erasmus Smith papers.” [3]

In their book The Tipperary Gentry, Hayes and Kavanagh tell us that Joseph Damer (c.1630–1720) was born in Dorset in England in 1630. [4] He came to Ireland after the restoration of Charles II when land was being sold cheaply by Cromwellian soldiers who were given land instead of pay but did not want to remain in Ireland. Joseph Damer bought land in Tipperary, settling at Shronell, and established himself as a moneylender, lending to other landowners on mortgages. He also became involved in banking in Dublin. His nephew John (1674-1768) acted as his agent in Tipperary.

Joseph had no children and left his vast fortune when he died in 1720 to his nephews John (1674-1768) and Joseph (1676–1737), sons of his brother George Damer. He was so wealthy that he entered folklore with tales of how he gained his wealth, and he was compared to King Midas, as if everything he touched turned to gold.

Jonathan Swift wrote a ditty mocking Joseph Damer’s parsimony:

“He walked the streets and wore a threadbare cloak

He dined and supped at charge of other folk

And – by his look – had he held out his palms

He might be thought an object fit for alms.“

The Dictionary of Irish Biography tells us:

“Despite his reputation for miserliness, Damer was a benefactor of presbyterianism and, by some accounts, unitarianism. He and his nephew John (1673?–1768) were among the trustees and managers of the General Fund established in 1710 to support the protestant dissenting interest; another fund was established in 1718 to support the congregation in New Row in Dublin.” [see 3]

The nephew John had no children and his brother Joseph (1676–1737) inherited. Joseph sat in the British parliament for Dorchester (1722–27) and became MP for Tipperary in 1735. He died two years later. He married Mary Churchill, daughter of John Churchill of Henbury, Dorset.

Robert O’Byrne tells us that his son Joseph (1717-1798) inherited the house and castle was later created the Earl of Dorchester. [5] He was an absentee landlord and his brother managed his Irish properties. He built a mansion named Damerville which was very grand, but was demolished in 1775. Their sister Mary married William Henry Dawson, 1st Viscount Carlow, who lived at Emo in Laois. It was her offspring who later inherited the Damer properties.

Joseph’s son John (1744-1776) married Ann Seymour, a sculptress. He spent all of his inheritance and killed himself. Subsequently it was his younger brother George who inherited the title to become 2nd Earl of Dorchester. None of Joseph’s offspring had children, however, so the properties passed to the 2nd Earl of Portarlington, a second cousin, who assumed the name Dawson-Damer.

Mary who had married the 1st Viscount Carlow had a son John Dawson (1744-1798) who became 1st Earl of Portarlington, Queen’s County. He married Caroline Stuart, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Bute and his writer wife, Mary Wortley Montagu. He commissioned James Gandon to built Emo Court in Queen’s County (Laois). It was his son John Dawson (1781-1845), 2nd Earl of Portarlington, who inherited the Damer fortune and lands, and added Damer to his surname.

Damer House has a scroll pediment doorway and inside, a magnificent carved staircase. The Irish Georgian Society was involved in saving it from demolition in the 1960s. [for more photographs, see https://theirishaesthete.com/tag/damer-house/ ] The stairs and floor in the front hall are original to the house. The stairs are similar to ones in Cashel Palace, which was the Archbishop’s Palace, and is now an upmarket hotel. See the website of the Irish Aesthete for photographs of this staircase: https://theirishaesthete.com/tag/cashel-palace/

The Damers didn’t live in the house and it was rented out to various tenants.

Robert O’Byrne tells us about the history of the house:

“In 1798 the house was leased as a barracks and then the whole site sold to the British military in 1858. At the start of the last century the Damer House became ‘Mr. French’s Academy’, a school for boys, reverting to a barracks for the National Army during the Civil War, then being used as a sanatorium, before once again in 1932 serving as a school until 1956, then a library. By 1970 it was empty and unused, and the local authority, Tipperary County Council, announced plans to demolish the house and replace it with an amenity centre comprising a swimming pool, car park, playground and civic centre (it had been nurturing this scheme since as far back as 1957). The council’s chairman wanted the demolition to go ahead, declaring that ‘as long as it stands it reminds the Irish people of their enslavement to British rule,’ and dismissing objectors to the scheme as ‘a crowd of local cranks.’ In fact, most of the so-called ‘crowd’ were members of the Old Roscrea Society and in December 1970 this organisation was offered help by the Irish Georgian Society in the campaign to save the Damer House.“

Upstairs in Damer House there’s also Exhibition space, but we did not have much time to browse.

After our tour of Damer House we crossed the yard for a tour of the castle.

Roscrea Castle fell into disrepair in the 19th century, and when the roof collapsed extensive repairs were needed in the 1850s. It was named a national monument in 1892, and is now under the care of the OPW.

The original entrance to the castle is to one side of where we enter today – you can see the drawbridge in the photograph above.

The Castle was located on one of the five main roads in ancient Ireland, and it was essential for the Normans to control this route. In 1315 King Edward II handed the castle over to James Butler, 1st Earl of Ormond.

The castle had many defensive features. The curtain wall is approximately three metres thick, which allowed for a wall-walk from which soldiers had a view of the surrounding area. The River Barrow formed a moat around the east face of the castle, and the Normans constructed a dry moat on the west side. The river was diverted in the 19th century.

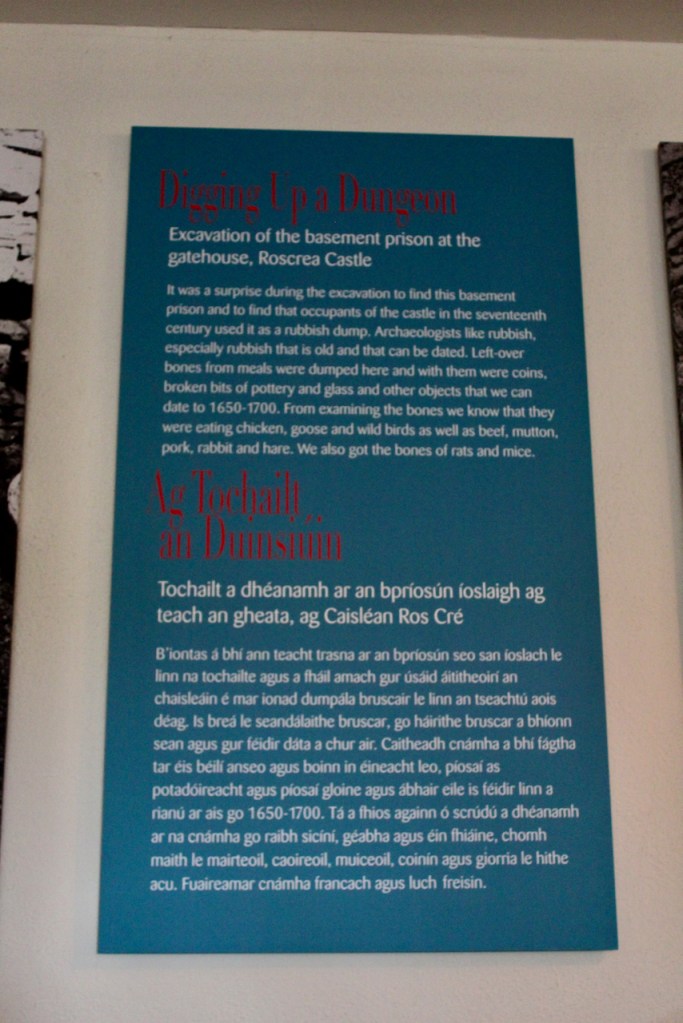

Inside the castle reception area there’s a grille on the floor, which is the “oubliette” (from the French, meaning “to forget.”). However, in this case, people were imprisoned here between court dates, the guide told us.

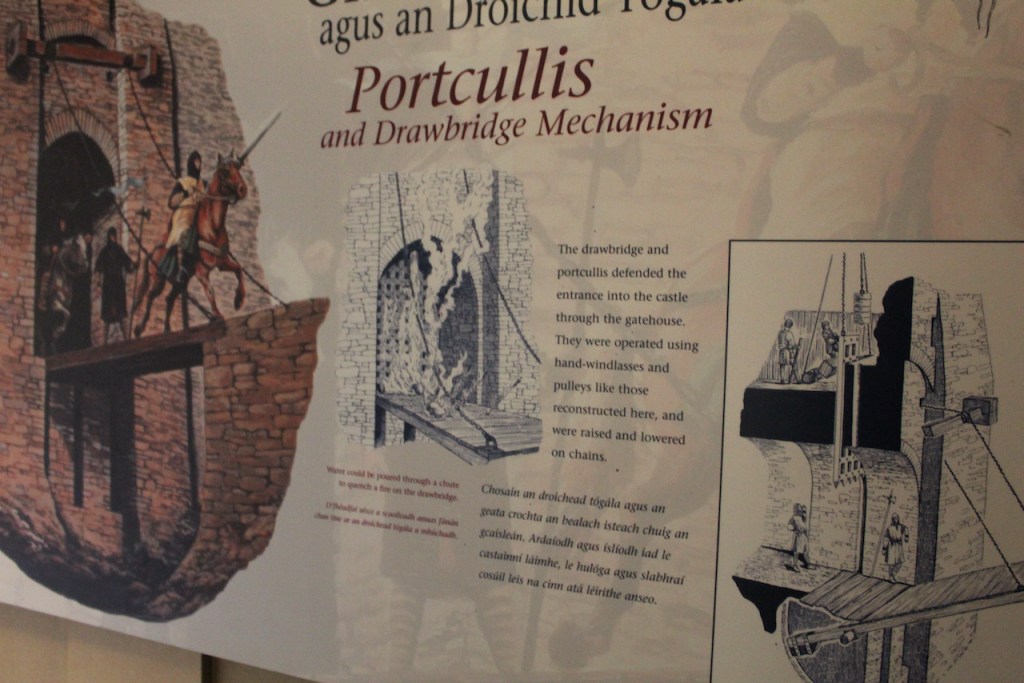

Above the drawbridge is a machicolation from which boiling substances could be dropped, and there are also arrow loop windows for defence. The stairs, called “trip steps” were deliberately built of different heights and widths to impede the intruder. The spiral clockwise to make it more difficult for the enemy to fight his way up the steps.

Silver from nearby silvermines would have been stored in the castle.

Eoin Roe O’Neill (d. 1649), at the head of 1,200 men, stormed Roscrea in 1646 and reportedly killed every man, woman and child. The only survivor was the governor’s wife, Lady Mary Hamilton (1605-1680), who was a sister to the Earl of Ormond [married to George Hamilton, 1st Baronet of Donalong County Tyrone and of Nenagh, County Tipperary]. She was again forced to play host in the castle to O’Neill three years later which again ended by the guests looting everything in sight. [7]

Larger windows were a later addition. Originally there would be only small loopholes. Before glass, the larger windows would be covered with skins to keep out the draught. The inside would have been limewashed, the white walls would then brighten the interior. The fireplace would also provide light.

The floor above the banquet room has three fireplaces. The large room was probably partitioned.

There’s a minstrils’ gallery. Minstrils were of the lower class and were kept away from aristocratic guests to prevent spreading any infection.

After our tour of the castle we had a little time to explore the gardens.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] See the blog of Patrick Comerford, http://www.patrickcomerford.com/search/label/castles?updated-max=2019-03-03T14:30:00Z&max-results=20&start=27&by-date=false

[3] https://www.dib.ie/biography/damer-joseph-a2390

[4] Hayes, William and Art Kavanagh, The Tipperary Gentry volume 1 published by Irish Family Names, c/o Eneclann, Unit 1, The Trinity Enterprise Centre, Pearse Street, Dublin 2, 2003.

[5] https://theirishaesthete.com/2013/09/23/bon-anniversaire/ and see my write-up about Emo Court, in OPW properties in Leinster: Laois.

[6] https://theirishaesthete.com/tag/damer-house/

[7] http://www.cahirhistoricalsociety.com/articles/cahirhistory.html

Galgorm Castle, County Antrim – now part of a golf club

Galgorm Castle – now part of a golf club, County Antrim

https://www.galgormcastle.com/galgorm-estate.html

The website tells us: “Galgorm Castle is an historic estate dating back to Jacobean times but has evolved into one of Northern Ireland’s most vibrant destinations with diverse business, golf and recreational activities housed there. The focal point is the 17th century Jacobean castle dating back to 1607, which has been restored and along with the immaculate walled gardens is part of the Ivory Pavilion wedding and events company. The castle is also a historical reminder of the important role the Galgorm Estate played as part of Northern Ireland’s history. Away from the championship golf course there is plenty of opportunity to try the game for the first time at the Fun Golf Area with a six-hole short course and Himalayas Putting Green. The Galgorm Fairy Trail is another family option which runs out of Arthur’s Cottage at the Fun Golf Area.And if looking for great food and drink, a meal at the Castle Kitchen + Bar at the Galgorm Castle clubhouse is a must. Members and non-members are welcome.”

The website contains a history of the Castle:

“Galgorm Castle is one of the finest examples of Jacobean architecture in Ireland. In May 1607, King James I granted the Ballymena Estate to Rory Og MacQuillan, a mighty warrior, famous for stating “No Captain of this race ever died in his bed,” (which thankfully means Galgorm Castle has one less ghost.). His Castle overlooks and dominates the 10th green and a network of souterrains at the fifth and eighth greens.

“Sir Faithful Fortescue (b. 1585) was the nephew Arthur Chichester. This name may have come from his habit of being particularly sharp in his dealings as he tricked Rory Og McQuillan out of estates and started to build Galgorm Castle in 1618. He might better have been known as Sir Faithless Fortescue as during the Civil War, in the heat of the battle of Edghhill, he changed sides from the Parliamentarians to the Cavaliers, but forgot to instruct his men to remove the orange sashes of the Parliamentarians so seventeen of them were slain by the Cavaliers as the enemy.

“Always known for turning a quick buck Sir Faithless sold the estate to the infamous Dr Alexander Colville [(c.1597-c.1679. He was a clergyman who became a wealthy landlord so it may have been malicious gossip that led to rumours)] who, as legend has it was an alchemist, reputed to have sold his soul to the devil for gold and knowledge. The stories of the good doctor are well documented and his portrait is not allowed to ever leave the castle or disaster will fall. His footsteps beat out a steady tattoo through the night as he does his rounds. Other nights, a ghostly light flickers around the park as he searches for his treasure, lost for over 300 years.

“The Youngs – rich linen merchants, bought the Estate in 1850 and their cousin Sir Roger Casement lived here for six years while he was at Ballymena Academy.

“The Duke of Wurtenburg made his headquarters at Galgorm following the Battle of the Boyne. The renowned Irish scholar Rose Young was born at Galgorm in 1865.

“During the 1980s, Christopher Brooke and his family inherited Galgorm Castle Estate and began developing his vision to turn Galgorm Castle into the one of Northern Ireland’s premier destinations, securing the Estate’s long-term future.”

“tootling”

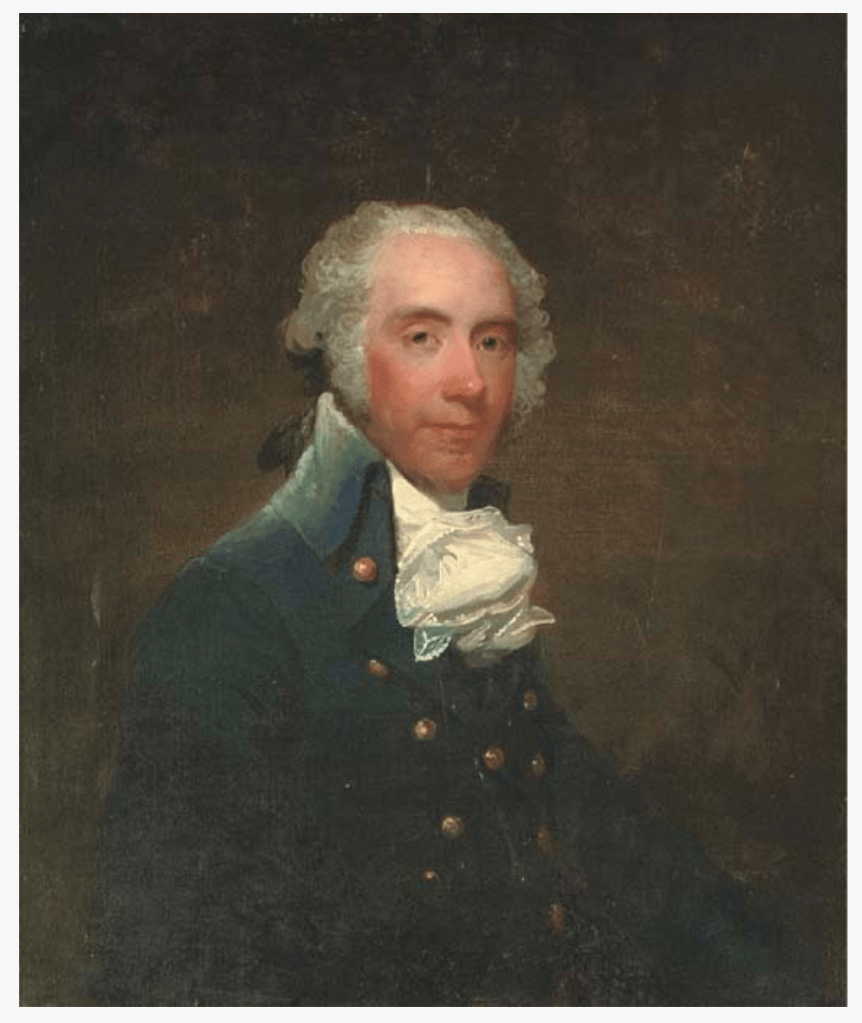

If you are a regular reader of this blog, you will know that along with visiting Section 482 properties and other “big houses” and castles that are open to the public, I am compiling a virtual Portrait Gallery of Ireland. I watch out online for portraits of Irish people who may become the subject of my website entries. Recently browsing portraits which were for auction with Christies Irish Auction in 2005, I came across a portrait of George Grierson of Rathfarnham House.

I was not familiar with Rathfarnham House so I looked it up online and found that it is an impressive former residence built in 1725, and later became part of Loreto Abbey. It was built for William Palliser (1695-1768), son of William Palliser (1646–1727) who was Church of Ireland Archbishop of Cashel. [1]

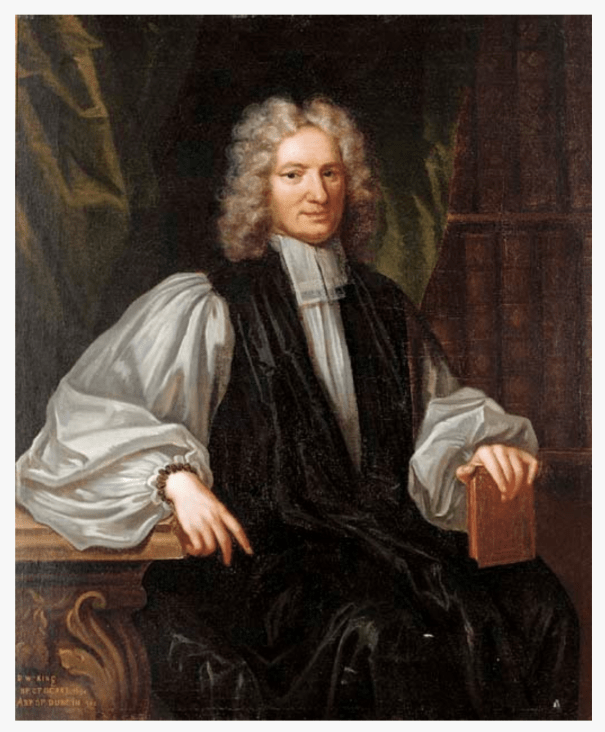

This ties in neatly with another portrait I came across, of William King (1650-1729) Archbishop of Dublin.

I had a previous photograph of a portrait of Archbishop William King from a visit to Trinity exam hall for a Trinity Book Sale.

I have an interest in Archbishop William King as he vouched for a Mark Baggot (d. 1718, buried in St. Audoen’s, Dublin) when Mark was losing his residence in Mount Arran, County Carlow. I don’t know if I am a descendant of Mark Baggot but I hope I am, as he is fascinating. Mark was one of the first members of the Dublin Philosophical Society. [2] I have gathered much information about Mark, but in short, when Mark, as a Catholic, was set to lose Mount Arran, he sought intercession from his friend William King. King vouched for Mark Baggot’s character. [3] The letters are in Trinity College Dublin. Mark and William King shared an interest in mathematics. Two of Mark Baggot’s books somehow made their way into Marsh’s Library – I have yet to see these books as when I requested them, they were being re-bound. I discovered today that William King’s library was bought by Archbishop Theophilus Bolton (d. 1744) and is held today in the University of Limerick in the Bolton Library. Mark was also a member of St. Anne’s Guild in Dublin, which was based in St. Audoen’s church.

We came across some of Mark’s descendants when we visited The Old Glebe in Newcastle Lyons, County Dublin (see my entry https://irishhistorichouses.com/2019/12/31/the-old-glebe-newcastle-lyons-county-dublin/), as James John Bagot (1784-1860) and his wife are buried in the graveyard of the adjoining church.

[1] https://source.southdublinlibraries.ie/handle/10599/7447?locale=en

“Loreto Abbey has as its core, Rathfarnham House, a mansion built in 1725 by William Palliser who expended considerable resources on its interior with polished mahogany and, in one room, embossed leather wallpaper. On his death in 1768 without children of his own, his cousin Reverend John Palliser inherited it. When he died in 1795, George Grierson, the King’s Printer purchased the house, from which he later moved to Woodtown House. The Most Reverend Dr Murray purchased it in 1821, after it lay vacant for some years, for the Loreto Order, then just founded. The first Superior of the Order, the Reverend Mother Francis Mary Teresa Ball made additions to the house, including supposedly an extra storey on to the house. A church was added in 1840, the novitiate in 1863, St Joseph’s wing in 1869 comprising concert hall and refectory, St Anthony’s wing St. Anthony’s wing in 1896, St Francis Xavier’s wing in 1903 and Liseux in 1932. Mother Theresa of Calcutta entered religion in Loreto Abbey in 1928. At its height it houses some 200 pupils. It cease to take boarders in 1996 and the building closed in 1999. A building company Riversmith Ltd acquired a site to the rear where it constructed apartments. The Loreto Order is now headquartered in Beaufort House, part of the Loreto High School.” Text by Kieran Swords.

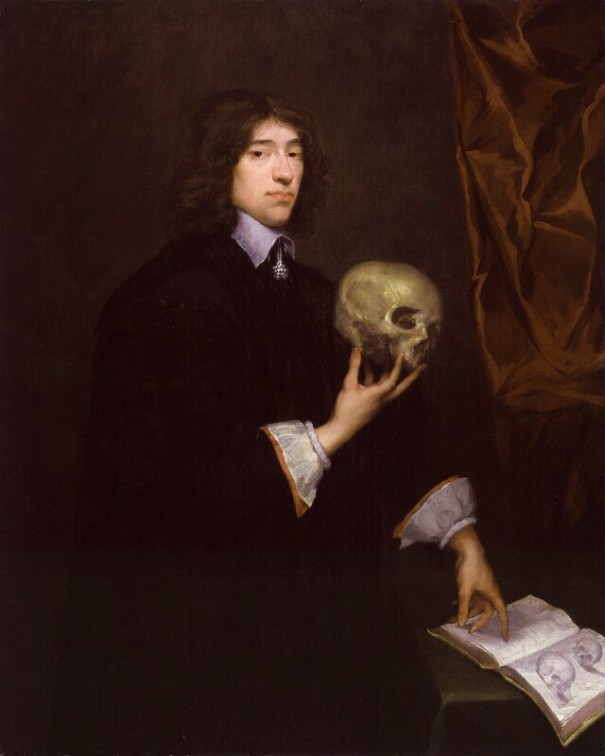

[2] Hoppen, K. Theodore, “The Dublin Philosophical Society and the New Learning in Ireland” Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 14, No. 54 (Sep., 1964), pp. 99-118 (20 pages). The Society was founded in 1683. The article tells us that the Dublin College of Physicians secured a royal charter in 1667. The Royal Society of London was founded in 1660, and George Tollett, a Dublin mathematics teacher, Narcissus Marsh, who was Bishop of Ferns and Leighlin at the time, and Allen Mullen, a Dublin physician, were in correspondence with it. In 1682 William Molyneux undertook to write a Natural History of Ireland, and in working, he met several other Irishmen interested in geography. He then set out to form the Dublin Society. He acquired the aid of Dr St George Ashe, then Rev Dr Huntington who was then provost of Trinity College. Within four months it had a membership of 14, and acquired permanent residence on Crow’s Nest off Dame Street in Dublin, where they established a laboratory, museum and herb garden. Other members were John Baynard, Archdeacon of Connor, Samuel Foley, a fellow of Trinity and later bishop, a physician John Willoughby who had studied in Padua, and Mark Baggot, Catholic. By 1685 a further 20 members had joined, including William King. William Petty became President and Edward Smyth, Treasurer.

Between 1687 and 1693 the weekly meetings were suspended due to political turmoil in Ireland. During the Williamite revolution many members fled to England. Dudley Loftus was temporarily a member but left as he didn’t like its progressive nature. The revival lasted only 18 months, but it was then revived again in 1707 by William Molyneux’s son Samuel. At this time members included Peter Browne the Provost of Trinity College Dublin, Samuel Dopping, and Thomas Burgh, the architect of Trinity College library, and philosopher George Berkeley. The Society ceased to meet in 1709.

Other members are listed in a Memoir, including: William Lord Viscount Mountjoy; John Worth, Dean of St. Patrick’s; Robert Redding, Bt; Cyril Wyche, Knight; Richard Bulkely, Knt. and Bt; Patrick Dun MD; Henry Fenerly; J. Finglass; Daniel Houlaghan; John Keogh; George Patterson, Surgeon; John Maden MD (his descendant Samuel Madden set up the Royal Dublin Society in 1731); Richard Acton; John Bulkeley; Paul Chamberlain; Robert Clements; Francis Cuff; Christopher Dominick; William Palliser later Archbishop of Cashel; Edward Smith, Professor of Mathematics and later Archbishop of Down and Connor; John Stanley; Jacobus Silvius; Jacobus Walkington; Paul Ricaut.

Subjects studied were Mathematics and Physics; Polite Literature; History and Antiquities; Medical Science including Anatomy, Zoology, Physiology, Chemistry.

[3] Mark Baggot, a major landowner in County Carlow, was the son of John Baggot who had forfeited as a Jacobite. Mark became friendly wiht George Tollet, later a powerful official in London, who was close to Archbishop King. See J.G. Simms, “Dublin in 1685” IHS xiv, 1965, p. 222-3. Baggot was also friendly with King due to their common interest in mathematics. When Baggot’s claim for restoration for his estate was before the trustees, Mark asked King to intercede on his behalf (see Baggot to King, 30 Jan 1701, TCD Lyons Collection MSS 1995-2008/754). King wrote to one of the trustees, Sir Henry Sheres, on Baggot’s behalf, citing Baggot’s links with Tollet who was a friend of Sheres. Baggot’s claim was allowed. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Savage, was acting as Counsel on Mark’s behalf. This was in spite of the fact that Mark’s estate had been granted to the Savages and later to the Wolseleys, and the fact that local Protestants had petitioned Ormond strongly to use his influence against Baggot’s restoration (see petition dated 16 April 1701, NLI Ormond MSS, MS 2457, f. 75). The petition accuses Baggot of “insufferable pride, rigour and insolence towards the Protestants here.”

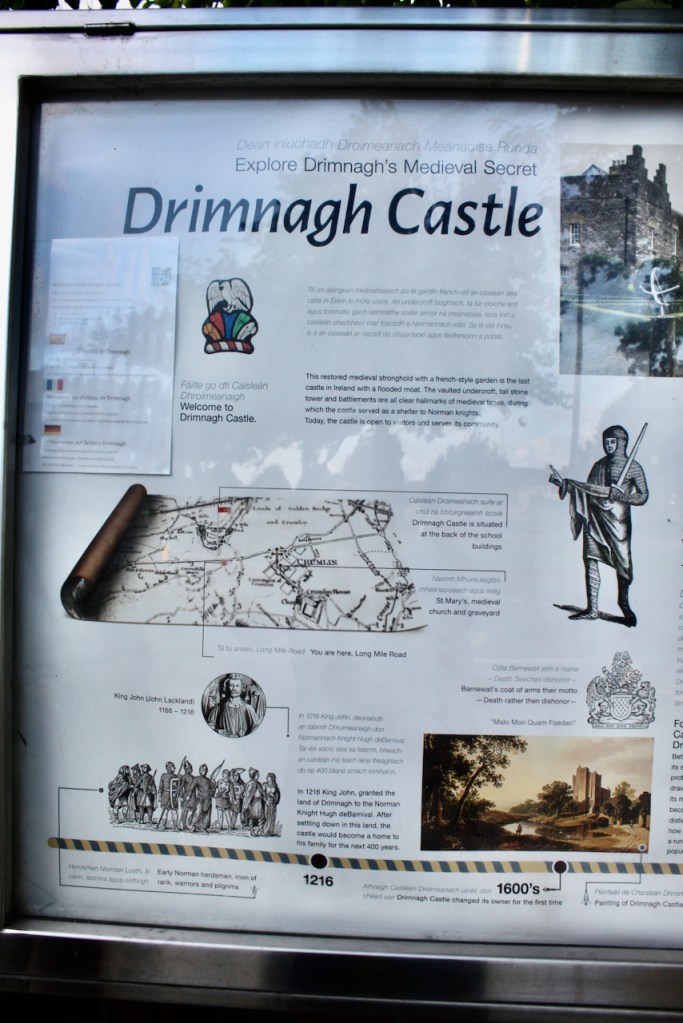

Drimnagh Castle, Dublin – open to public

See the website for opening times. It is also available for hire, and we attended a party there in 2015!

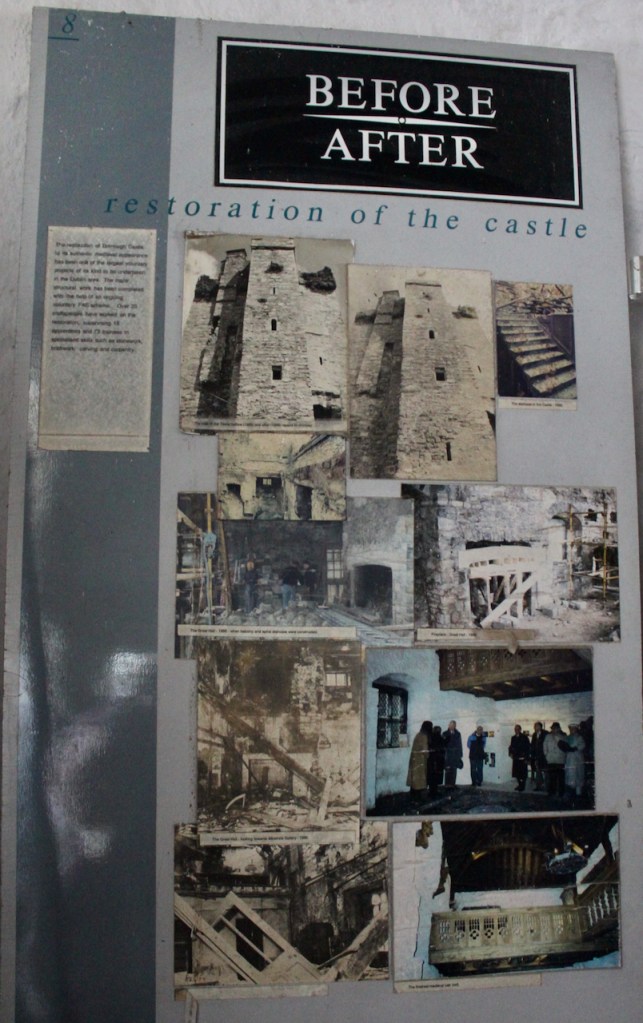

We visited again in 2023, with a tour given by Peter Pearson for the Irish Georgian Society. Peter Pearson was instrumental in saving the Castle from destruction. In 1985 he “swung across the moat on a rope” to see the state of the building, which had been unoccupied since the 1960. Many individuals and organisations were involved in the early stages of restoration, including An Taisce, FAS, CYTP, and the Drimnagh and Crumlin community. Over 23 craftspeople worked on the restoration, supervising 15 apprentices, and 73 trainees in specialised skills such as stonework, brickwork, carving and carpentry.

The website tells us: “Nestled in the heart of South Dublin, Drimnagh Castle stands as a meticulously restored Norman Castle, boasting the distinction of being the sole remaining moated castle in Ireland. Once the esteemed seat of the de Bernival family, who were granted lands in Drimnagh and Terenure by King John in 1215, the castle now serves primarily as a cherished heritage site.” King John granted the land to Hugh alias Ulfran de Barneville.

“Guided tours offer visitors the opportunity to explore the castle and its enchanting gardens. Moreover, the castle is available for hire, making it an ideal venue for presentations, School projects, product launches, photo shoots and even as a captivating film location!“

The website describes the Castle: “Its rectangular shape enclosing the castle, its gardens and courtyard, created a safe haven for people and animals in times of war and disturbance. The moat is fed by a small stream, called the Bluebell. The present bridge, by which you enter the castle, was erected in 1780 and replaced a drawbridge structure.“

I took notes the day Peter Pearson gave the tour but I don’t have them to hand so will have to add more information to this entry later!

The website continues: “Above the entrance of the tower, as the visitor comes through the large gateway is a ‘murder hole’. Rocks, stones, boiling water or limestone were poured down upon the head of any enemy attempting to break in. The main castle to the right of the tower was built in the 15th century, and the tower was built in the late 16th. The porch and stairways were built in the 19th century and the other buildings are 20th century.“

The walls of the castle are built of local grey limestone known as calp and the stone was probably drawn from one of the many nearby quarries. The walls are about 3-4 feet thick.

The website tells us “The tower was built in the late 16th or early 17th century. The tower is approximately 57 feet high and commands a great view of the surrounding countryside. Most of the castles at Ballymount, Terenure and Rathfarnham could have been seen from the top of the battlements.“

The website tells us: “In 1215 the lands of Drymenagh and Tyrenure were granted to a Norman knight, Hugo de Bernivale, who arrived with Strongbow. These lands were given to him in return for his family’s help in the Crusades and the invasion of Ireland. De Bernivale selected a site beside the “Crooked Glen” , the original Cruimghlinn, that gives its name to the townland of Crumlin, and there he built his castle. This “Crooked Glen” is better known today as Landsdowne Valley, through which the river Camac makes its way to the sea. The lands around Drimnagh at this time were rising and falling hills and vast forests stretching to the Dublin mountains. All through the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries the area around the castle was sparsely populated and a document shows that only around 11 people lived in the area during the 18th century.“

In The Landed Gentry and Aristocracy Meath, volume 1, by Art Kavanagh, published in 2005 by Irish Family Names, Dublin 4, he tells us that as a result of the foray into Ireland by the Bernevals in 1215 with Prince John, they were granted lands in Dublin in the Drimnagh, Kimmage, Ballyfermot and Terenure areas, where they settled until Cromwellian times.

The website tells of: The early years of the Barnewalls at Drimnagh Castle

“The Barnewall’s (anglicised from De Berneval) were not just owners of land in Drimnagh, but owned land and fortified castles all over Ireland, such as Crickstown and Trimblestown. They were involved in many events in Irish history and held positions in Irish Parliament and in military campaigns against the Irish. The Barnewall family crest has powerful warrior symbols and a Latin inscription, “I would rather die than dishonour my name”. You can see a reproduction of this crest over the fireplace in the Great Hall in the now restored castle.”

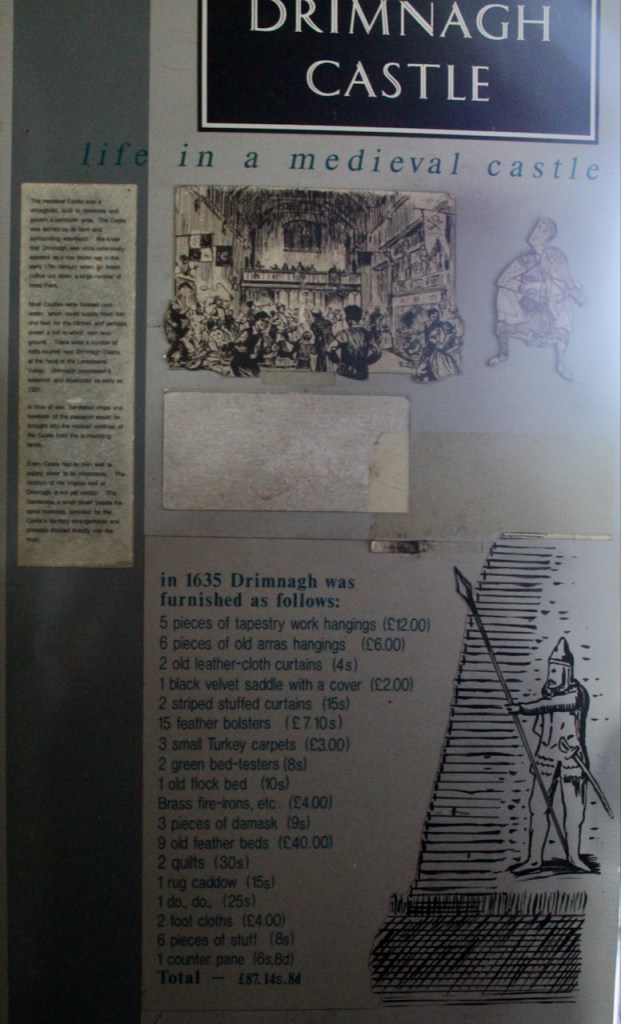

An information board in the castle tells us that in 1435 Luke Barnewall became trustee of the lands in Drimnagh Castle, including three houses, two mills and a dovecote.

An information board in the castle tells us that a medieval castle was a stronghold built to dominate and govern an area. The castle was served by its farm and surrounding woodland. Drimnagh was once extensively wooded. There were also mills located near Drimnagh Castle, as early as 1331.

The website tells us that: “[The Drimnagh Barnewall line] terminated in an heiress, Elizabeth, daughter of Marcus Barneval of Drumenagh, who married James Barnewall of Bremore, and sold the property, 1st February 1607, to Sir Adam Loftus, Kt. of Rathfarnham.“

This must be Adam Loftus (1568-1643) 1st Viscount of Ely. He held the office of Archdeacon of Glendalough, co. Wicklow between 1594 and 1643. and was appointed Knight in 1604. He was appointed Privy Counsellor (P.C.) [Ireland] in 1608, and held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) for King’s County between 1613 and 1615. He held the office of Lord Chancellor [Ireland] between 1619 and 1638. He was created 1st Viscount Loftus of Ely, King’s Co. [Ireland] on 10 May 1622.

In Cromwell’s time Drimnagh and its lands were granted to Lieutenant Colonel Philip Ferneley, a relation of Adam Loftus, who lived in the castle until his death in 1677. Some time in he 17th century the defensive nature of the castle was changed and it became a more comfortable residence with large mullioned windows to let in more light. A massive fireplace in the great hall was created around that time also.

In 1727 Walter Bagenal of Dunleckney, County Carlow, who had married Eleanor Barnewall, daughter of James of Bremore, County Meath, sold the castle to the John Fitzmaurice Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne, later generations of Petty and Petty-Fitzmaurice were the Marquesses of Lansdowne. This family leased the castle to various farmers throughout the 19th century.

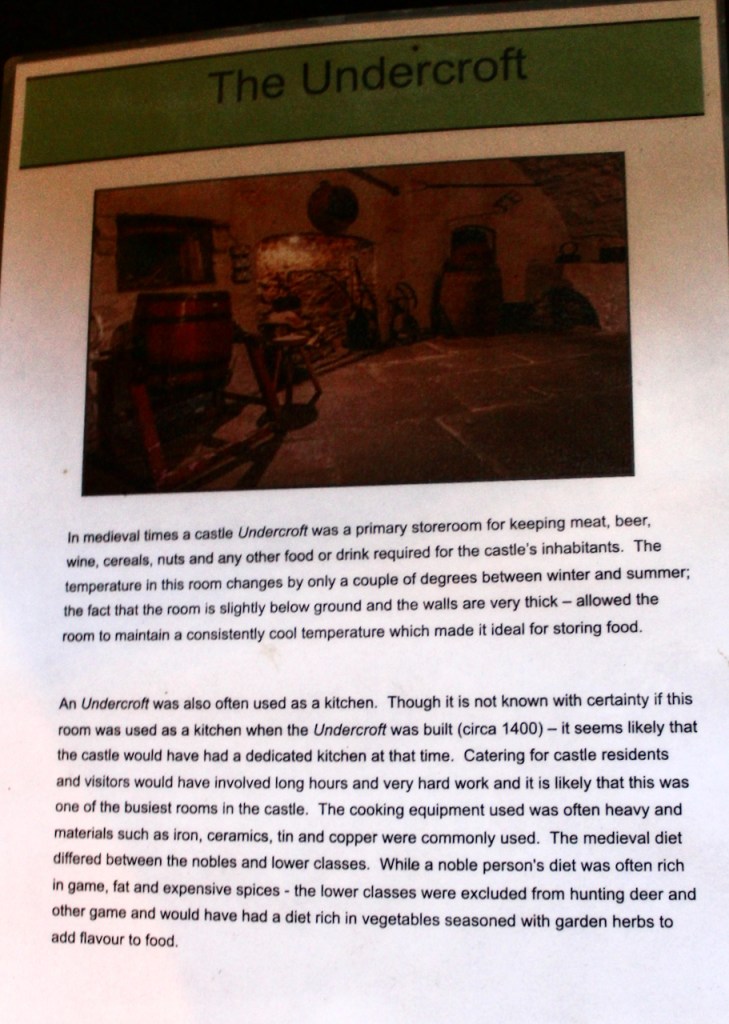

The website tells us: “The undercroft was built as a storage room for food; it also doubled up as a refuge if the castle was attacked. The fireplace and bread and smoking oven are recreations of the kitchen that was here in the 19th century. The narrow stairs leading up to the next floor are unique in that they turn to the left, unlike most Norman castles which turn to the right.“

The restoration work started in June 1986 and over 200 workers were involved in the repair work, including stonemasons, woodcarvers, metal workers, plasterers, tilers and artists. The restoration of the the roof was inspired by Dunshoughly Castle in Fingal, and was built using Roscommon Oak which is renowned for its great durability and strength. The roof was constructed in the courtyard and was then raised onto the castle at a cost of 50,000 Punts (Irish £). The floor of the great hall was re-tiled with tiles taken from St. Andrews Church in Suffolk Street in Dublin. Some of the contemporary handmade tiles are replicas of medieval flooring, many decorated with Barnewall emblems.

The website tells us: “The great hall was originally an all-purpose living room/sleeping quarters in the 13th century. During the day tables and benches were placed in the centre of the floor for dining. At night straw or reed matting was laid on the floor and the occupants of the castle slept on this covering.“

The website tells us more about the history of the castle: “Drimnagh has seen its fair share of raids and attacks by the O’Toole Clans through the years and there is record of two of the Barnewalls of Drimnagh being killed in a skirmish near Crumlin. There are many undocumented raids and battles. In the 19th century, after these tumultuous times Drimnagh saw the arrival of industries like the paper mill at Landsdowne valley and other enterprises. Small Inns and lodges were built to house travellers on their way to Tallaght or further afield. Some of these are still in business today, such as the Red Cow and The Halfway House. Buildings of note in the area around the early 19th century were the Drimnagh Lodge, The Halfway House, Drimnagh Castle.

“After the 19th century we see more and more expansion out towards the Drimnagh area, but it was in the 20th century were we see housing estates and industrial estates springing up around Drimnagh. For more modern historical info please visit the Drimnagh Residents Associations excellent page on its history.“

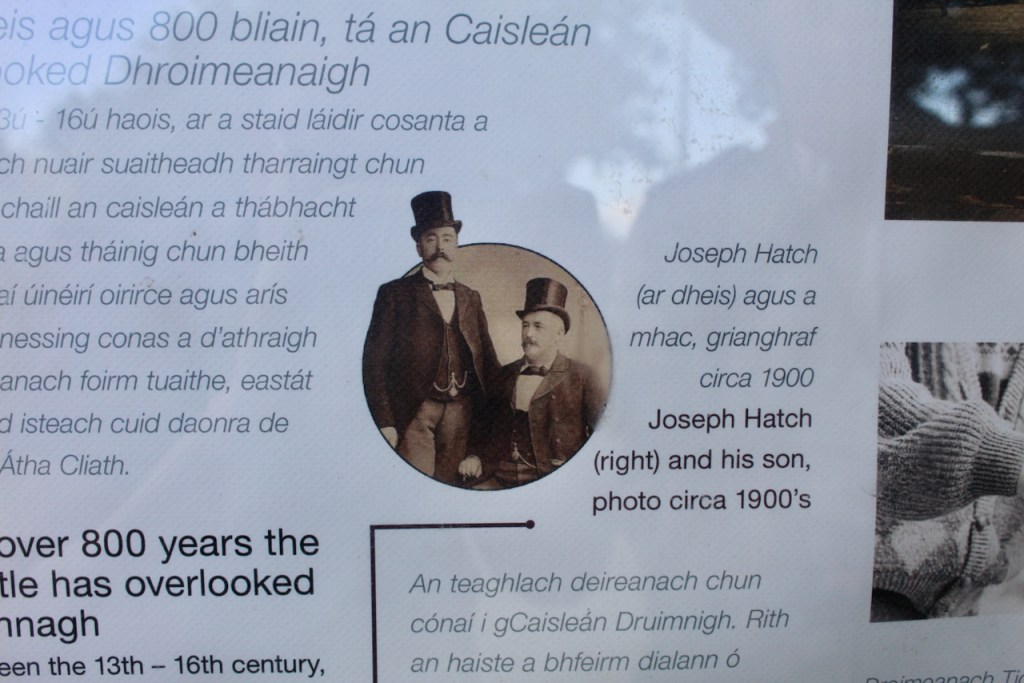

The website tells us of more recent inhabitants, the Hatch family:

“In the early 20th century, the castle and its surrounding lands found a new custodian in Joseph Hatch (born 1851), a prominent dairy man from 6 Lower Leeson Street. Serving as a dedicated member of Dublin City Council for Fitzwilliam Ward from 1895 to 1907, Joseph Hatch acquired the castle in the early 1900s to provide ample grazing land for his cattle.

“Passionate about preserving the heritage, Joseph Hatch undertook the restoration of the castle, transforming it into a charming summer retreat for his family. The castle also served as the picturesque venue for significant family milestones, including the celebration of Joseph and his wife Mary Connell’s silver wedding anniversary and the marriage of their eldest daughter, Mary, in 1910.“

“Following Joseph Hatch’s passing in April 1918, the castle became the legacy of his eldest son, Joseph Aloysius, affectionately known as Louis. Alongside his brother Hugh, Louis managed the family dairy farm and the accompanying dairy shop on Lower Leeson Street. Despite never marrying, Louis dedicated himself to the estate until his death in December 1951. Hugh, who married at the age of 60 in 1944, passed away in 1950.“

“The Hatch family continued to occupy Drimnagh Castle until the mid-1950s. Subsequently, Louis Hatch bequeathed the estate to Dr.P. Dunne, the Bishop of Nara. Dr Dunne, in turn, sold the castle (allegedly for a nominal sum) to the Christian Brothers. This transaction paved the way for the construction of the school that now proudly stands adjacent to the castle.“

The restoration work was completed in 1991 and was opened to the public by the then President of Ireland Mary Robinson. Since then the castle has hosted banquets, weddings, book launches and many more events. The castle is now maintained by a small group of dedicated people who keep the castle looking great for future generations to come.

There are further rooms upstairs.

The castle’s gardens have been developed, with a Parterre:

The website tells us: “A parterre is a formal garden construction on a level surface consisting of planting beds, edged in stone or tightly clipped hedging, and gravel paths arranged to form a pleasing, usually symmetrical pattern. It is not necessary for a parterre to have any flowers at all. French parterres originated in 15th-century Gardens of the French Renaissance. The castle parterre is a simple symmetrical design of four squares, divided into four triangular herb beds. The centre point of the squares feature a clipped yew tree while the centre point of each herb bed features a shaped laurel bay tree.

”One of the most important household duties of a medieval lady was the provisioning and harvesting of herbs and medicinal plants and roots. Plants cultivated in the summer months had to be harvested and stored for the winter. Although grain and vegetables were grown in the castle or village fields, the lady of the house had a direct role in the growth and harvest of household herbs.

”Herbs and plants grown in manor and castle gardens basically fell into one of three categories: culinary, medicinal, or household use. Some herbs fell into multiple categories and some were grown for ornamental use.” The website tells of some of these plants.

The gardens also have an alley of hornbeams:

“The common English “hornbeam tree” derives its name from the hardness of the wood, and was often used for carving boards, tool handles, shoe lasts, coach wheels, and for other uses where a very tough, hard wood is required. The plant beds either side of the trees, feature snowdrops, bluebells, tulips, daffodils, some ferns and hellebores.

”Hornbeam leaves are popular for their use in external compresses to stop bleeding. Their haemostatic properties also help in the quick healing of wounds, cuts, bruises, burns and other minor injuries. A yellow dye is obtained from the bark.“

After our tour inside, Peter brought us outside to show us more of the gardens surrounding the castle, and to have a look at the outer walls of the castle and the moat.

14 Henrietta Street, Dublin – museum

14 Henrietta Street is a social history museum of Dublin life, from one building’s Georgian beginnings to its tenement times. We connect the history of urban life over 300 years to the stories of the people who called this place home. The website tells us:

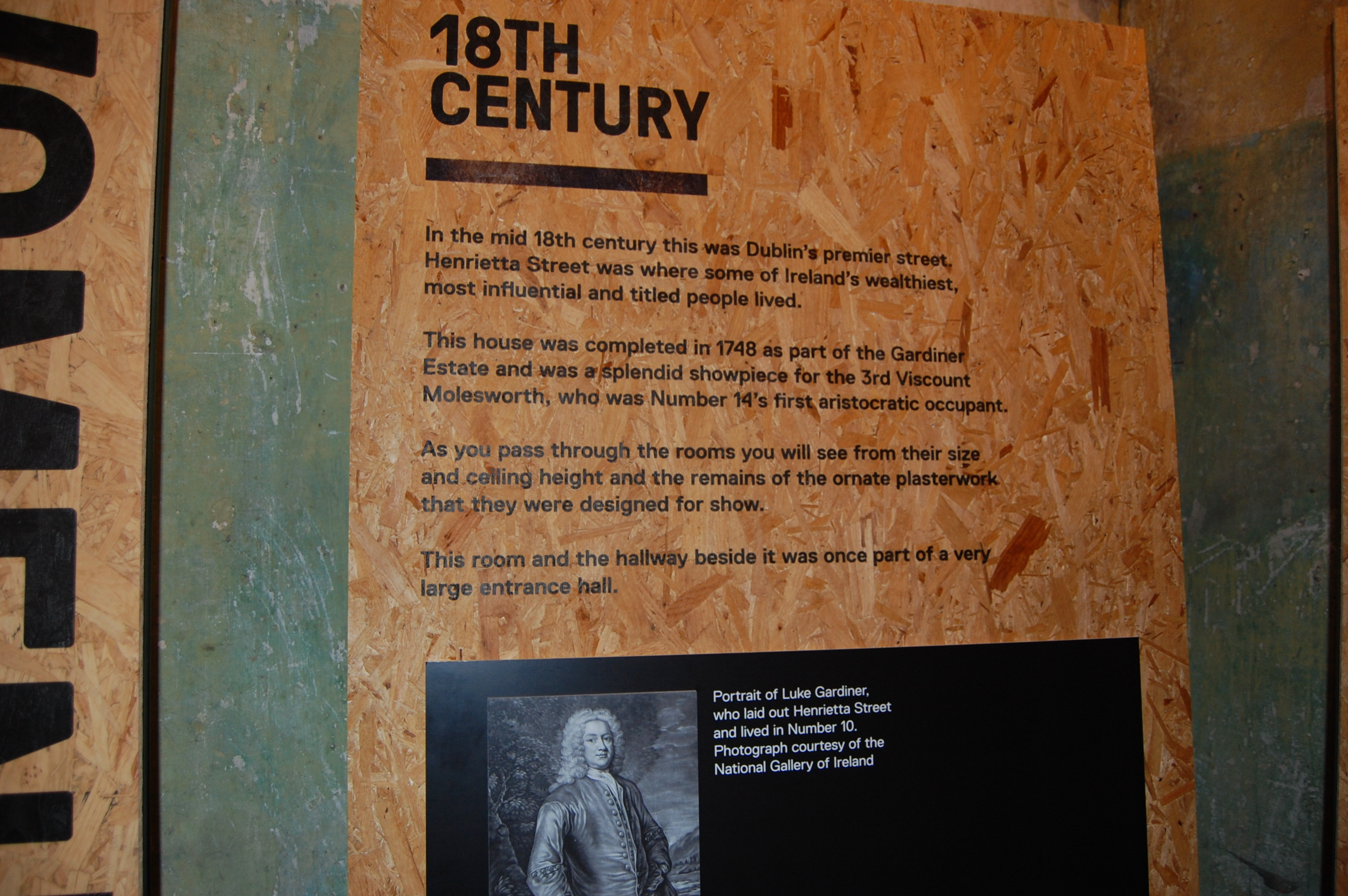

“Henrietta Street is the most intact collection of early to mid-18th century houses in Ireland. Work began on the street in the 1720s when houses were built as homes for Dublin’s most wealthy families. By 1911 over 850 people lived on the street, over 100 of those in one house, here at 14 Henrietta Street.“

“Numbers 13-15 Henrietta Street were built in the late 1740s by Luke Gardiner. Number 14’s first occupant was The Right Honorable Richard, Lord Viscount Molesworth [1670-1758, 3rd Viscount Molesworth of Swords] and his second wife Mary Jenney Usher, who gave birth to their two daughters in the house. Subsequent residents over the late 18th century include The Right Honorable John Bowes, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Lucius O’Brien, John Hotham Bishop of Clogher, and Charles 12th Viscount Dillon [1745-1814].}

The street was named after the wife of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the time, Henrietta Crofts.

The website continues: “Number 14, like many of the houses on Henrietta Street, follows a room layout that separated its public, private and domestic functions. The house is built over five floors, with a railed-in basement, brick-vaulted cellars under the street to the front, a garden and mews to the rear, and there was originally a coach house and stable yard beyond.“

“In the main house, the principal rooms in use were located on the ground and first floors. On these floors, a sequence of three interconnecting rooms are arranged around the grand two-storey entrance hall with its cascading staircase. On the ground floor were the family rooms which consisted of a street parlour to the front, a back eating parlour, a dressing room or bed chamber for the Lord of the house, and a closet.“

“On the first floor level, the piano nobile (or noble floor), were the formal public reception rooms. A drawing room to the front is where the Lord or Lady would host visitors, along with the dining room to the back. The dressing room or bed chamber for the lady of the house, and a closet were also on this floor. Family bedrooms were located on the floor above the piano nobile, and the servants quarters were located in the attic. A second back stairs would have provided access to all floor levels for family and servants alike.“

“These grand rooms began as social spaces to display the material wealth, status and taste of its inhabitants. Dublin’s Georgian elites developed a taste for expensive decoration, fine fabrics, and furniture made from exotic materials, such as ‘walnuttree’ and mahogany.“

“After the Acts of Union were passed in Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, all power shifted to London and most politically and socially significant residents were drawn from Georgian Dublin to Regency London. Dublin and Ireland entered a period of economic decline, exacerbated by the return of soldiers and sailors at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.“

“This marked a turning point for the street – professionals moved in, and Henrietta Street was occupied by lawyers. Between 1800 and 1850 14 Henrietta Street was occupied by Peter Warren, solicitor, and John Moore, Proctor of the Prerogative Court.

“In the 19th century the rooms of the house took on a different more utilitarian tone. Fine decoration and furniture gave way to desks, quills and paperwork with the activities of commissioners, barristers, lawyers, and clerks who moved into the house.

“Family life returned to the street in the early 1860s when the Dublin Militia occupied the house until 1876, when Dublin became a Garrison town, with their barracks at Linenhall.“

“From 1850-1860 the house was the headquarters of the newly established Encumbered Estates’ Court which allowed the State to acquire and sell on insolvent estates after the Great Famine.“

“Dublin’s population swelled by about 36,000 in the years after the Great Famine, and taking advantage of the rising demand for cheap housing for the poor, landlords and their agents began to carve their Georgian townhouses into multiple dwellings for the city’s new residents.“

“In 1876 Thomas Vance purchased Number 14 and installed 19 tenement flats of one, three and four rooms. Described in an Irish Times advert from 1877:

‘To be let to respectable families in a large house, Northside, recently papered, painted and filled up with every modern sanitary improvement, gas and wc on landings, Vartry Water, drying yard and a range with oven for each tenant; a large coachhouse, or workshop with apartments, to be let at the rere. Apply to the caretaker, 14 Henrietta St.’

“In Dublin, a tenement is typically an 18th or 19th century townhouse adapted, often crudely, to house multiple families. Tenement houses existed throughout the north inner city of Dublin; on the southside around the Liberties, and near the south docklands.“In Dublin, a tenement is typically an 18th or 19th century townhouse adapted, often crudely, to house multiple families. Tenement houses existed throughout the north inner city of Dublin; on the southside around the Liberties, and near the south docklands.“

“Houses such as 14 Henrietta Street underwent significant change in use – from having been a single-family house with specific areas for masters, mistresses, servants, and children, they were now filled with families – often one family to a room – the room itself divided up into two or three smaller rooms – a kitchen, a living room, and a bedroom. Entire families crammed into small living spaces and shared an outside tap and lavatory with dozens of others in the same building.“

“By 1911 number 14 was filled with 100 people while over 850 lived on the street. The census showed that it was a hive of industry – there were milliners, a dressmaker (tailoress!), French polishers, and bookbinders living and possibly working in the house.“

“With the establishment of the new state, improvements to housing conditions in Dublin became a priority. In 1931 Dublin Corporation appointed its first city architect Herbert Simms to improve the standard of housing in the city. Simms and his team created new communities outside the city centre, amidst greenery and fresh air, this was the dawn of the suburbs. The development of these new communities signalled the end of tenement life in Dublin.“

“The last tenement residents of number 14 left in the late 1970s by which time the building was virtually abandoned by its owners after the basement and third floor (attic) had already become uninhabitable. During this period of neglect the processes of decay accelerated, leading to the rotting of structural timbers, loss of decorative plasterwork, and vandalism, leaving the house close to imminent collapse.

Dublin City Council began a process to acquire the house in 2000, and as a result of the Henrietta Street Conservation Plan and embarked on a 10-year long journey to purchase, rescue, stabilise and conserve the house, preserving it for generations to come.

In September 2018 14 Henrietta Street opened to the public.“

I am a fan of Mary Wollestonecraft, and am delighted with the connection to the house next to this address, 15 Henrietta Street, which was owned by the King family.

“In 1786, on the far side of the wall in number 15, Mary Wollstonecraft was governess to Lord and Lady Kingsborough’s children. As tutor to Margaret King she instilled a wish for equal rights and republican ideals in her charge. She had an aspiration to be treated equally in a society where she was expected to fend for herself as most ladies of the ascendancy had to when suitors were not to be had or dowries were scarce. Governesses to wealthy families held a precarious middle ground between servant and family friend. In 1792 she would publish an important feminist treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Women.”

“Wollstonecraft gives us a look at a Dublin where women were expected to abide by what she regarded as oppressive social rules: “Dublin has not the advantages which result from residing in London; everyone’s conduct is canvassed, and the least deviation from a ridiculous rule of propriety… would endanger their precarious existence”.”

See also the wonderfully informative book, The Best Address in Town: Henrietta Street, Dublin and its First Residents 1720-80 by Melanie Hayes, published by Four Courts Press, Dublin 8, 2020.

Ormond Castle, Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary, an OPW property

Ormond Castle, Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary:

We haven’t been back to Ormond Castle recently but we visited it in May 2018, and I am republishing this entry, previously posted under “Office of Public Works Properties in County Tipperary.” I’m still catching up with write-ups so don’t have anything new to publish today.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/ormond-castle/:

“Joined on to an earlier medieval riverside castle, Ormond Castle Carrick-on-Suir is the finest example of an Elizabethan manor house in Ireland. Thomas, 10th Earl of Ormond [“Black Tom” (1531-1614)], built it in 1565 in honour of his distant cousin Queen Elizabeth.

“The magnificent great hall, which stretches almost the whole length of the building is decorated with some of the finest stucco plasterwork in the country. The plasterwork features portraits of Queen Elizabeth and her brother Edward VI and many motifs and emblems associated with the Tudor monarchy.“

The castle has a low and wide-spreading addition to an older castle, which consisted of two massive towers set rather close together. The castle is joined to these towers by a return at each side, making an enclosed courtyard.

The facade is of two storeys with three gables and a central porch and oriel. It is only one room thick. It is virtually unfortified, having no basement, and windows only three feet from the ground, and a few shot-holes for defence by hand-guns, Craig points out. The windows on the ground floor may have been widened at some point.

Mark Bence-Jones writes:

“The house, which is horseshoe shaped, forming three sides of a small inner court, and the castle the fourth. The house is of 2 storeys with a gabled attic; the towers of the castle rise behind it. The gables are steep, and have finials; there are more finials on little piers of the corners of the building. There are full-sized mullioned windows on the ground floor as well as on the floor above, the lights having the slightly curved heads which were fashionable in late C16. There is a rectangular porch-oriel in the centre of the front, and an oriel of similar form at one end of the left-hand side elevation. The finest room in the house is a long gallery on the first floor, which had two elaborately carved stone chimneypieces – one of which was removed to Kilkenny Castle 1909, but has since been returned – and a ceiling and frieze of Elizabethan plasterwork. The decoration includes busts of Elizabeth I, who was a cousin of “Black Thomas,” Ormonde through her mother, Anne Boleyn, and used to call him her “Black Husband”: she is said to have promised to honour Carrick with a visit. The old castle served as part of the house and not merely as a defensive adjunct to it: containing, among other rooms, a chapel with carved stone angels.” [3]

Thomas Butler (1582-1614) the 10th Earl of Ormond is a fascinating character. He was the eldest son of James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond, and his wife Joan Fitzgerald, daughter of the 10th Earl of Desmond. Because he was dark-haired, he was known to his contemporaries as “Black Tom”or “Tomas Dubh”. As a young boy, Thomas was fostered with Rory O’More, son of the lord of Laois (his mother was granddaughter of Piers Rua Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond) before being sent to London to be educated with the future Edward VI. He was the first member of the Butler family to be brought up in the protestant faith. In 1546, he inherited the Ormond earldom following the sudden death of his father. He fought against the Fitzgerald Earls of Desmond in the Desmond Rebellions, as he was loyal to the British monarchy. He was made Lord Treasurer of Ireland and a Knight of the Garter.

He was highly regarded by Queen Elizabeth to whom he was related through her mother Anne Boleyn. Anne Boleyn was the granddaughter of the 7th Earl of Ormond making Elizabeth and Thomas cousins. Thomas married three times but left no heir and was succeeded by his nephew Walter Butler 11th Earl of Ormond. He died in 1614 and was buried in St Canice’s cathedral, Kilkenny.

James Butler the 12th Earl of Ormond and 1st Duke of Ormond (1610-1688) spent much of his time here and was the last of the family to reside at the castle. On his death in 1688 the family abandoned the property and it was only handed over to the government in 1947, who then became responsible for its restoration.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] https://repository.dri.ie/

[3] Mark Bence-Jones. A Guide to Irish Country Houses (originally published as Burke’s Guide to Country Houses volume 1 Ireland by Burke’s Peerage Ltd. 1978); Revised edition 1988 Constable and Company Ltd, London.