General information: 052 744 1011, cahircastle@opw.ie

Stephen and I visited Cahir Castle in June 2022, and I was very impressed. I had no idea that we have such an old castle in Ireland with so much intact.

From the OPW website https://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/cahir-castle/:

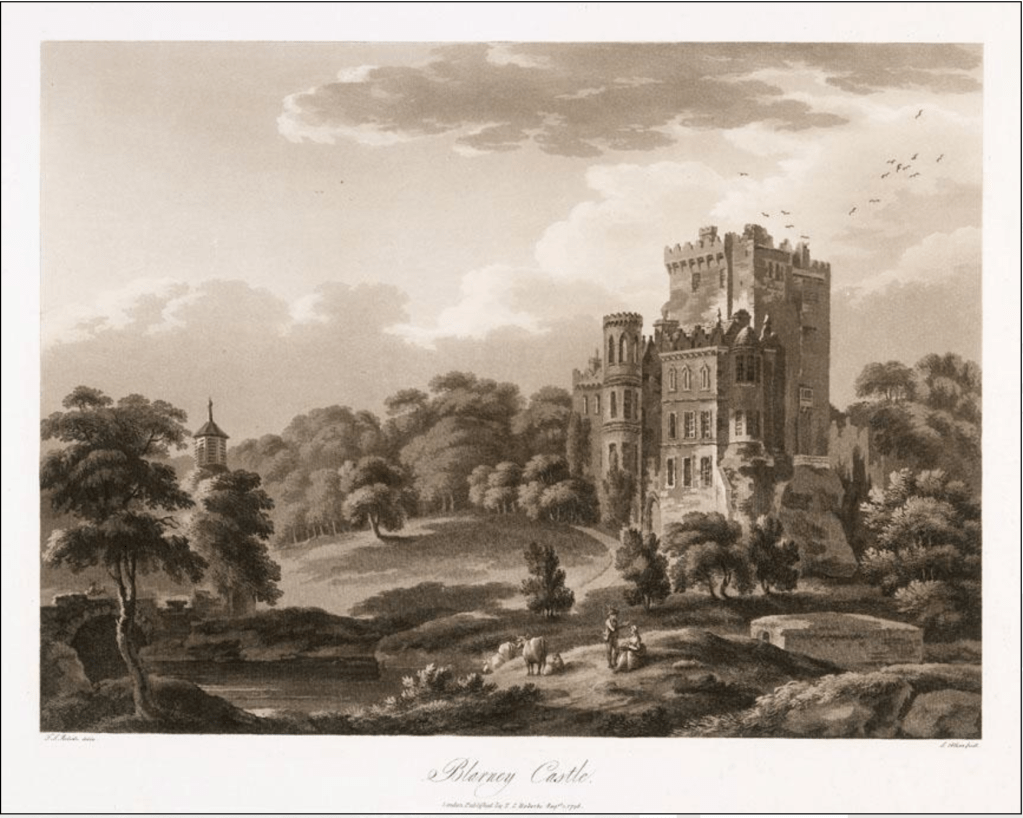

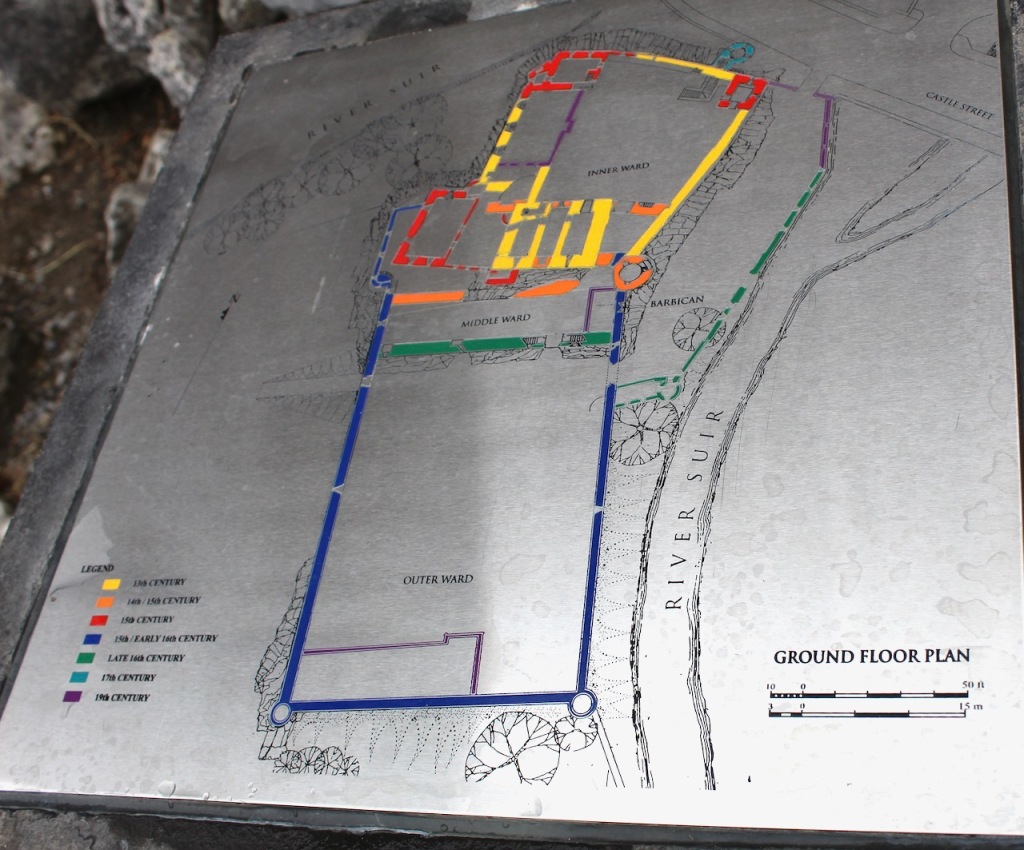

“Cahir Castle is one of Ireland’s largest and best-preserved castles. It stands proudly on a rocky island on the River Suir.

“The castle was was built in the thirteenth century and served as the stronghold of the powerful Butler family. [The Archiseek website tells us it was built in 1142 by Conor O’Brien, Prince of Thomond] So effective was its design that it was believed to be impregnable, but it finally fell to the earl of Essex in 1599 when heavy artillery was used against it for the first time. During the Irish Confederate Wars it was besieged twice more.

“At the time of building, Cahir Castle was at the cutting edge of defensive castle design and much of the original structure remains.“

Our tour guide took us through the castle as if we were invaders and showed us all of the protective methods used. We were free then to roam the castle ourselves.

The name derives from the Irish ‘an Chathair Dhun Iascaigh’ meaning stone fort of the earthen fort of the fish.

The information leaflet tells us that the area was owned by the O’Briens of Thomond in 1169 at the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion. The area around Cahir was granted to Phillip of Worcester in 1192 by John, Lord of Ireland, who later became King John. His nephew William was his heir – I’m not sure of his surname! But then his great-granddaughter, Basilia, married Milo (or Meiler) de Bermingham (he died in 1263). They lived in Athenry and their son was the 1st Lord Athenry, Piers Bermingham (died 1307).

Edward III (1312-1377) granted the castle to the James Butler 3rd Earl of Ormond in 1357 and also awarded him the title of Baron of Cahir in recognition of his loyalty. The 3rd Earl of Ormond purchased Kilkenny Castle in c. 1392. Cahir Castle passed to his illegitimate son James Gallda Butler. James Gallda was loyal to his mother’s family, the Desmonds, who were rivals to his father’s family, the Butlers.

In their book The Tipperary Gentry, William Hayes and Art Kavanagh tell us that the rivalry between the Butlers of Ormond and the Fitzgeralds of Desmond turned to enmity when the War of the Roses broke out in England, with the Ormonds supporting the House of Lancaster and the Desmonds the House of York. The enmity found expression in the battle at Pilltown in 1462. The enmity continued for over a century, and the last private battle between the Ormonds and the Desmonds was the Battle of Affane, County Waterford, in 1565. [2]

A descendant of James Gallda Butler, Thomas Butler (d. 1558) was elevated to the peerage of Ireland, on 10 November 1543, by the title of Baron of Caher (of the second creation). He married Eleanor, a daughter of Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (d. 1539) and Margaret Fitzgerald, daughter of Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare (d. 1513). His son Edmund became the 2nd Baron (d. 1560) but as there were no legitimate male heirs the title died out.

It was Piers Rua Butler, the 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467–1539), who brought peace between the warring factions of Fitzgeralds of Desmond and the Butlers of Ormond. He married Margaret Fitzgerald, daughter of Gerald (or Garret) Fitzgerald (1455-1513) 8th Earl of Kildare. His efforts culminated in a treaty called the Composition of Clonmel. It stated that Edmund Butler of Cahir should receive the manor of Cahir on condition that he and all his heirs “shall be in all things faithful to the Earl [of Ormond] and his heirs.” The Barons of Cahir were not allowed to keep their own private army nor to exact forced labour for the building or repair of their castle or houses. (see [2]).

The brother of Thomas 1st Baron Caher, Piers Butler (d. after February 1567/68) had a son Theobald (d. 1596) who was then created 1st Baron Caher (Ireland, of the 3rd creation) in 1583. [3]

There’s an excellent history of Cahir on the Cahir Social and Historical Website:

“Throughout the reigns of Elizabeth I and Charles I, Cahir Castle appears as a frequent and important scene in the melancholy drama of which Ireland was a stage. The Castle was taken and re-taken, but rarely damaged and through it all remained in the hands of the Roman Catholic Butlers of Cahir. By this time Cahir had become a great centre of learning for poets and musicians. Theobald, Lord Cahir [I assume this was 1st Baron Cahir of second creation who died in 1596] was said by the Four Masters “to be a man of great benevolence and bounty, with the greatest collection of poems of any of the Normans in Ireland”. [4]

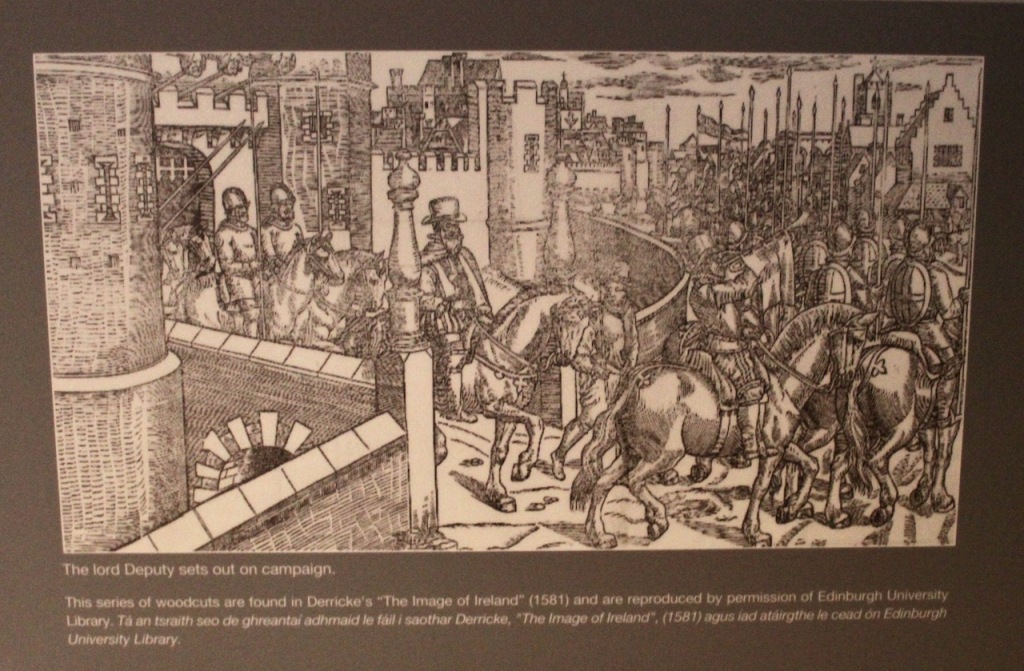

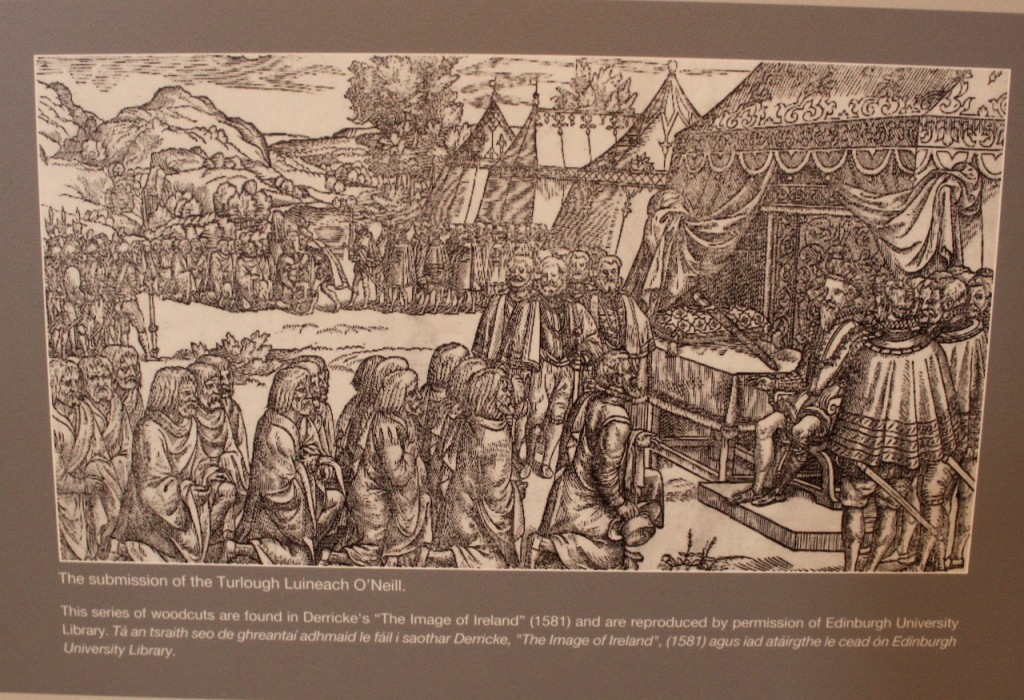

This storyboard tells us that Ireland was dramatically different from Renaissance England in its language, customs, religion, costume and law. It was divided into 90 or so individual “lordships” of which about 60 were ruled by independent Gaelic chieftains. The rest were ruled by Anglo-Irish lords. Queen Elizabeth saw Ireland as a source of much-needed revenue. She did not have sufficient resources nor a strong enough army to conquer Ireland so she encouraged her authorities in Dublin to form alliances between the crown and any local chieftains who would submit to her authority. Many chieftains who submitted did so in order to assist them in their own power struggles against their neighbours. Elizabeth especially needed this support in order to ensure that if Spain invaded Ireland she would be able to quell rebellion.

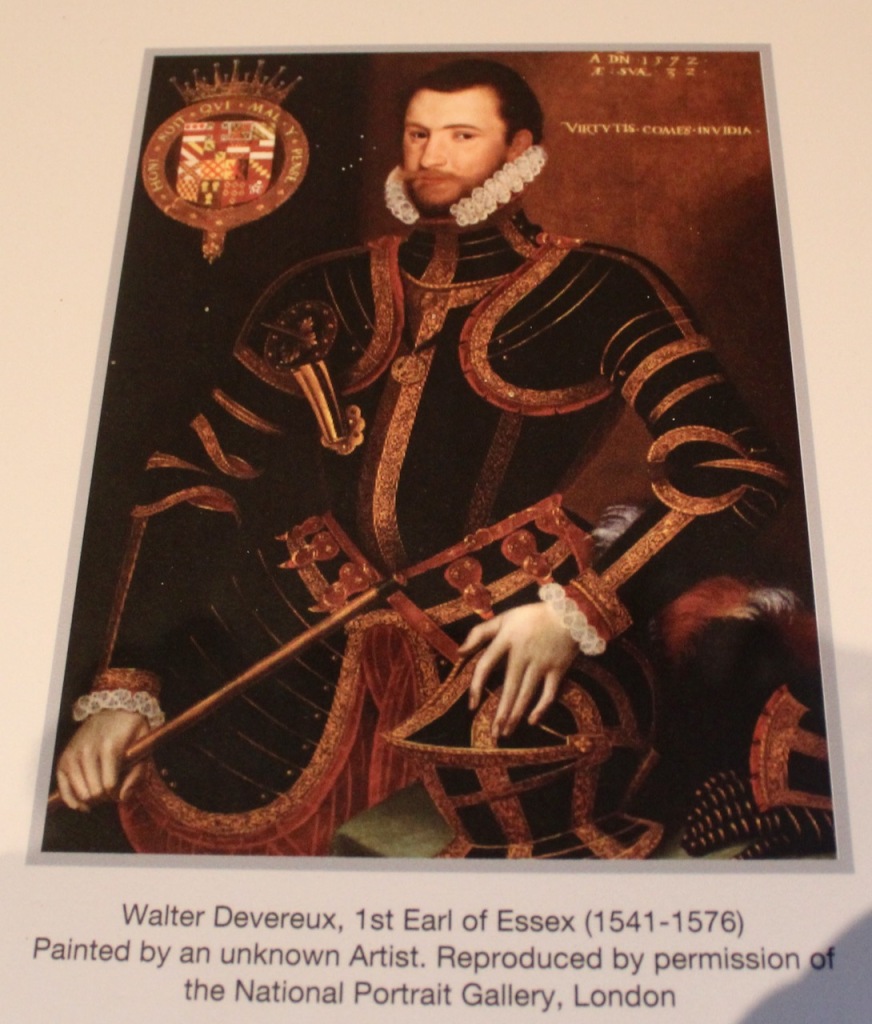

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, travelled to Ireland to subjugate Ulster and Shane O’Neill (“The O’Neill) in 1573. He failed, and had to sell of much of his land in England to pay debts accrued from raising an army. He died in Dublin of typhoid in 1576.

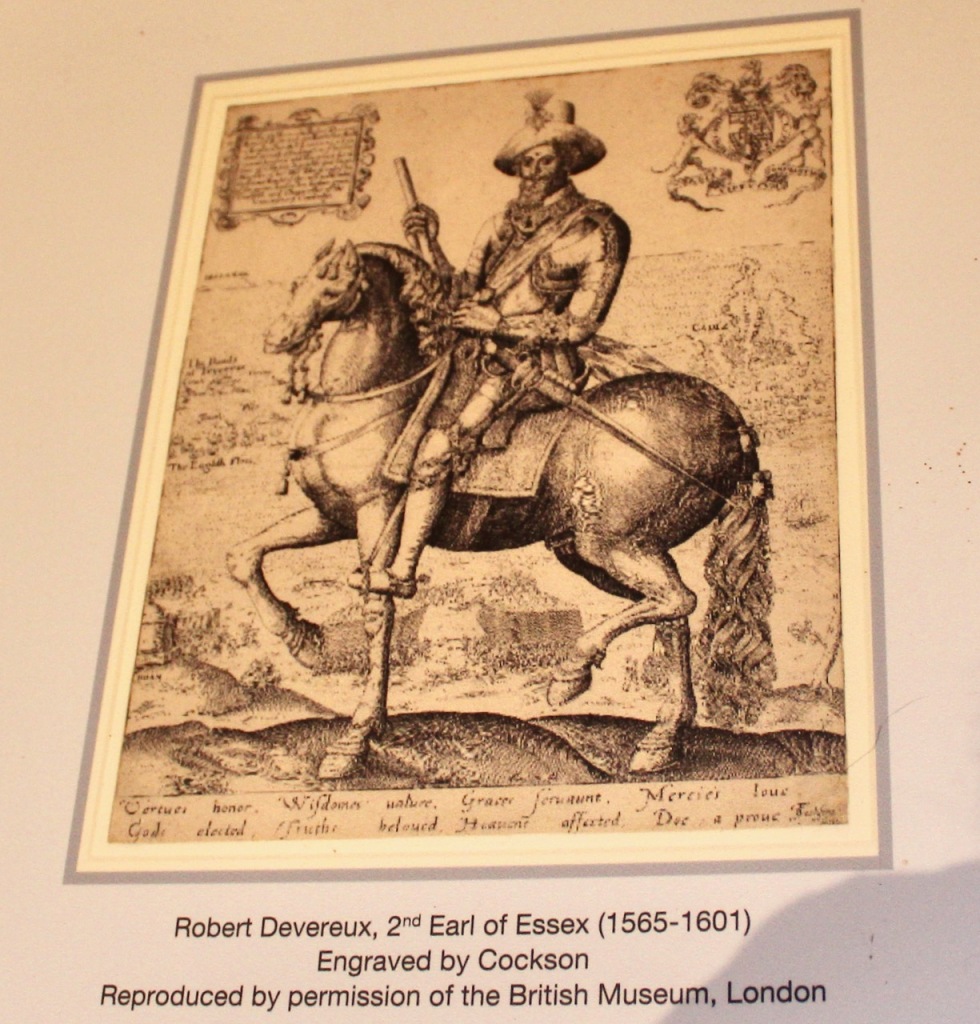

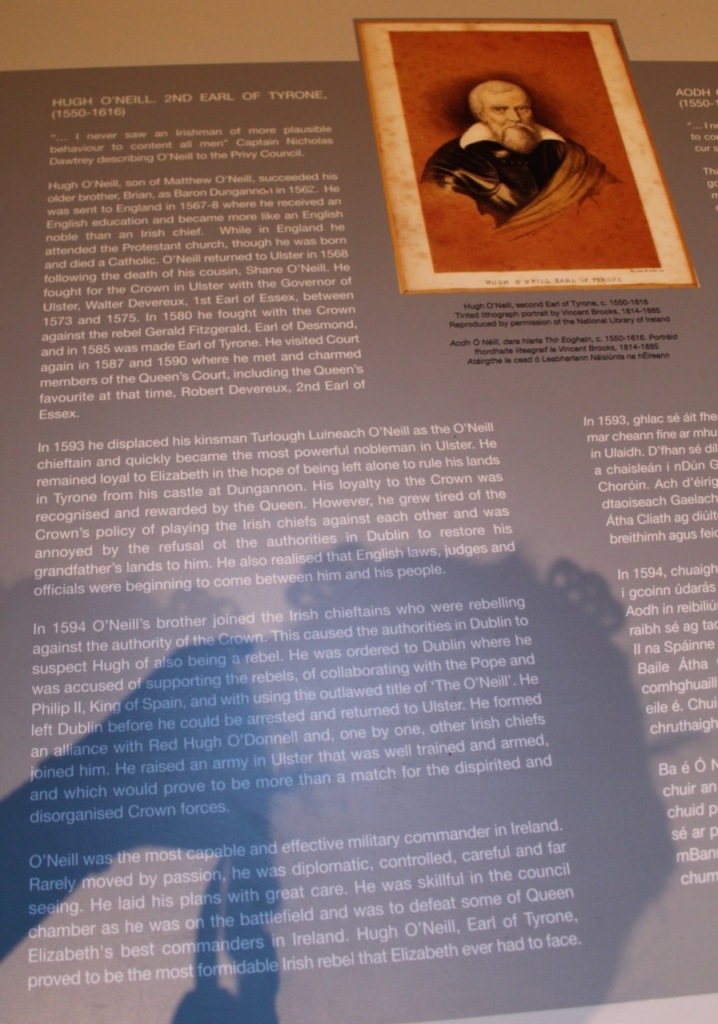

His son, the 2nd Earl of Essex came to Ireland to quell a rebellion which included the rise of Hugh O’Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone (1550-1616), cousin of Shane O’Neill.

The storyboard tells us that Hugh O’Neill fought alongside the 1st Earl of Essex in Ulster between 1573 and 1575. He also fought for Queen Elizabeth in 1580 against the rebel Gerald Fitzgerald, 14th Earl of Desmond (circa 1533, d. 11 November 1583), and as thanks he was made Earl of Tyrone. However, he turned against the crown in 1594 and formed an alliance with Red Hugh O’Donnell to fight against the Queen’s troops, in the Nine Years War.

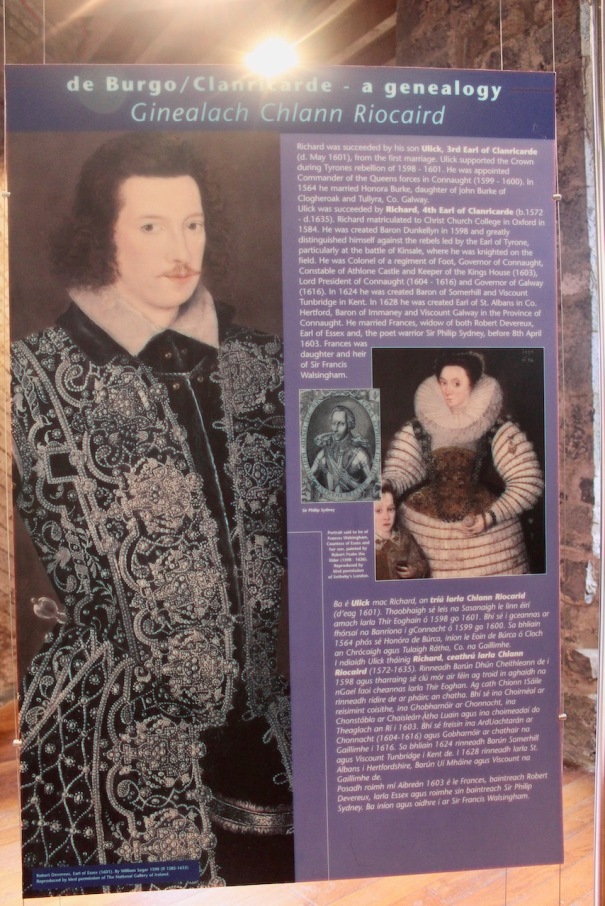

The ties between the Earls of Essex and Queen Elizabeth I are complicated. When Walter Devereux the 1st Earl died in Ireland, his wife, Lettice Knollys, remarried. She and Queen Elizabeth’s favourite, Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester, married secretly, a fact which enraged the disappointed Queen. It was Robert Dudley who introduced his stepson Robert Devereux 2nd Earl of Essex to Elizabeth and he subsequently became her favourite, alongside Walter Raleigh. However, Elizabeth was to be angered again when this next favourite, Devereux, also secretly married, this time to Frances Walsingham, who was the widow of Sir Philip Sidney. We came across her before when we visited Portumna Castle as she later married Richard Bourke 4th Earl of Clanricarde. Philip Sidney was the son of Henry Sidney (or Sydney) who had been Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Robert Devereux the 2nd Earl of Essex sought to re-win courtly favour by going to fight in Ireland, following the footsteps of his father, and persuaded Elizabeth to name him Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

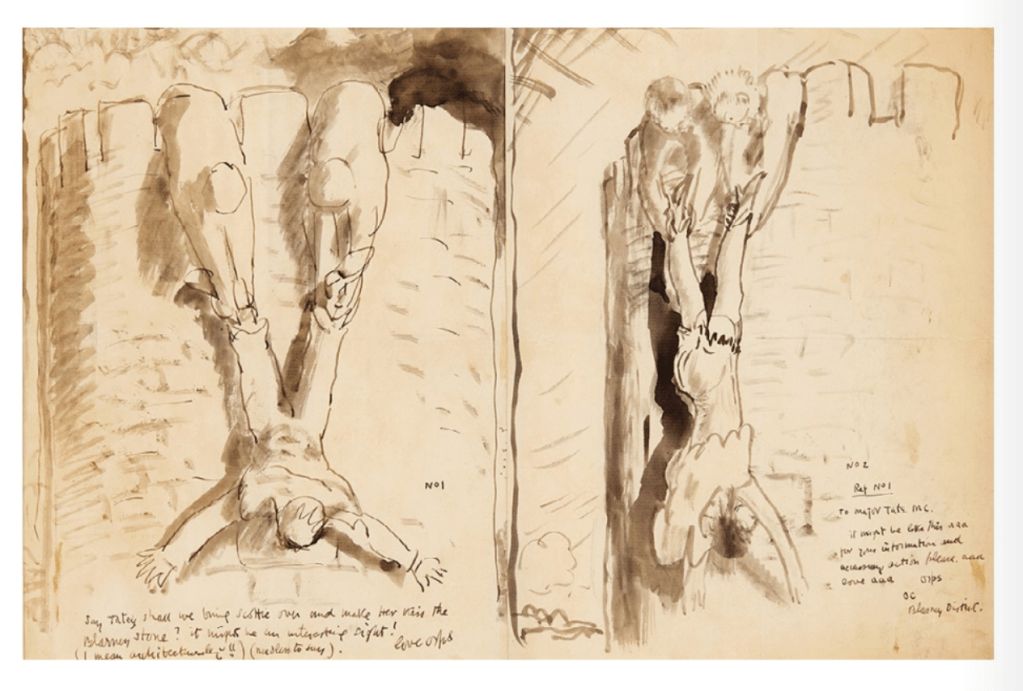

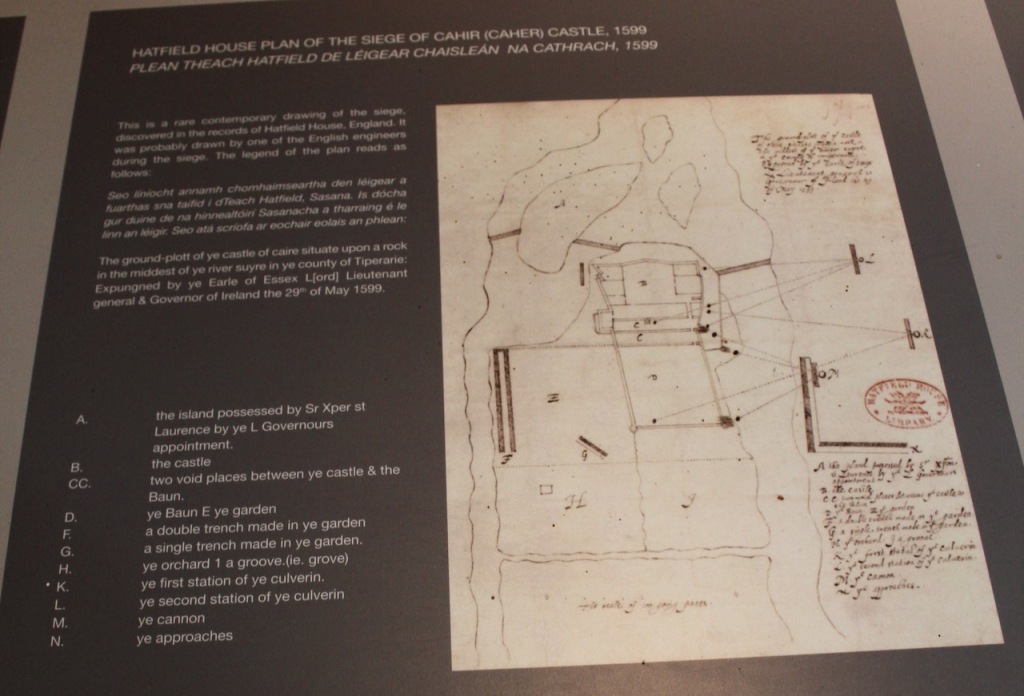

In May 1599, Essex and his troops besieged Cahir Castle. He arrived with around two to three thousand men, a cannon and a culverin, a smaller and more accurate piece of heavy artillery.

Thomas Butler the 10th Earl of Ormond, who owned the castle in Carrick-on-Suir and was another favourite of the Queen, as he had grown up with her in the English court. However, the storyboards tell us that he at first rebelled, alongside Thomas Butler 2nd Baron Cahir (or Caher – they seem to be spelled interchangeably in historical records) and Edmond Butler, 2nd Viscount Mountgarret (1540-1602), another titled branch of the Butler family.

By the time of the 1599 siege, the Earl of Ormond was fighting alongside Essex, and Cahir Castle was held by rebels, including Thomas Butler’s brother James Gallada Butler (not to be confused with the earlier James Galda Butler who died in 1434). Thomas Butler 2nd Baron Cahir travelled with Essex toward the castle. Baron Cahir sent messengers to ask his brother to surrender the castle but the rebels refused. Thomas Butler 2nd Baron Cahir was suspected of being involved with the rebels. Thomas was convicted of treason but received a full pardon in 1601 and occupied Cahir Castle until his death in 1627. James Gallada Butler claimed that he had been forced by the rebels to fight against Essex. Essex and his men managed to capture the castle.

During the three days of the siege, the castle incurred little damage, mostly because the larger cannon broke down on the first day! Eighty of the defenders of the castle were killed, but James Gallada Butler and a few others escaped by swimming under the water mill. This siege was to be the only time that castle was taken by force. James Gallada recaptured the castle the following year and held it for some months. The Butlers regained possession of the castle in 1601.

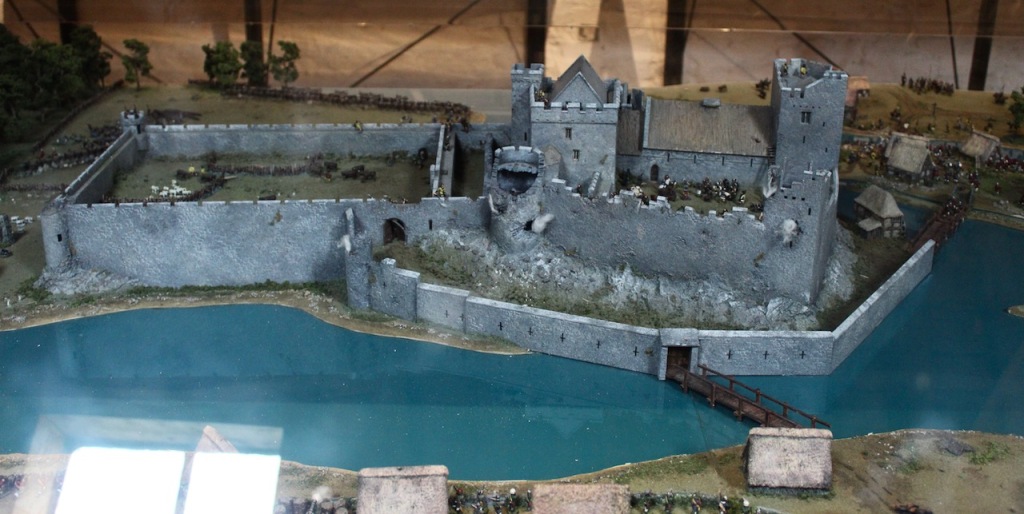

Inside the castle in one room was a wonderful diorama of this siege of Cahir Castle, with terrifically informative information boards.

Failing to win in his battles in Ireland, however, Essex made an unauthorised truce with Hugh O’Neill. This made him a traitor. The Queen did not accept the truce and forbid Essex from returning from Ireland. He summoned the Irish Council in September 1599, put the Earl of Ormond in command of the army, and went to England. He tried to raise followers to oust his enemies at Elizabeth’s court but in doing so, he brought a small army to court and was found guilty of treason and executed.

The Cahir Social and Historical Website continues:

“A study of the Butler Family in Cahir in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries reveals the rise and fall of one of the minor branches of the House of Ormond. At the end of the fifteenth century, they possessed extensive powers, good territorial possessions and a tenuous link with the main branch of the Butler family. During the sixteenth century, their possession was strengthened by the grant of the title of Baron of Cahir with subsequent further acquisition of land, but they came under closer central government control.”

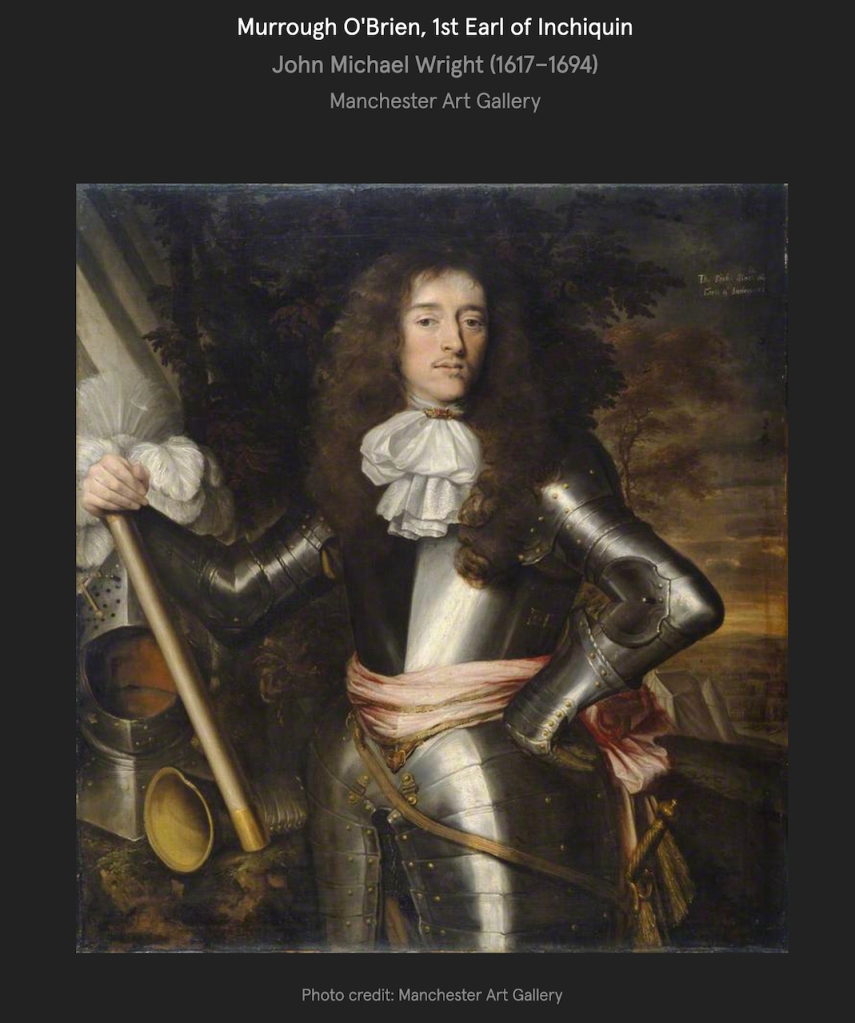

The Cahir website continues: “A complete reversal in their relations with the Earls of Ormond occurred, strengthened by various marriage alliances. They also participated in political action, both in the Liberty of Tipperary and at National Level. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries their position was affected by their adherence to Roman Catholicism, which resulted in their revolt during the Nine Years War, and subsequent exclusion from power by the Central Administration. They formed part of the Old English Group and as such, suffered from the discriminatory politics practiced by the Government. From 1641 they became minor landowners keeping their lands by virtue of the favour of their relative, the Duke of Ormond. In 1647 the Castle was surrendered to Lord Inchiquin for Parliament but re-taken in 1650 by Cromwell himself, whose letter describing acceptable terms of surrender still survives.

Murrough O’Brien fought on the side of the Crown – his ancestor Murrough O’Brien was created 1st Baron Inchiquin in 1543 by the Crown in return for converting to Protestantism and pledging allegiance to the King (Henry VIII). Since he took the castle for the crown, it implies that at this time Lord Caher fought against the crown again – and since the information boards tell us that the 1599 siege was the only time it was taken by force, force must not have been used at this later time.

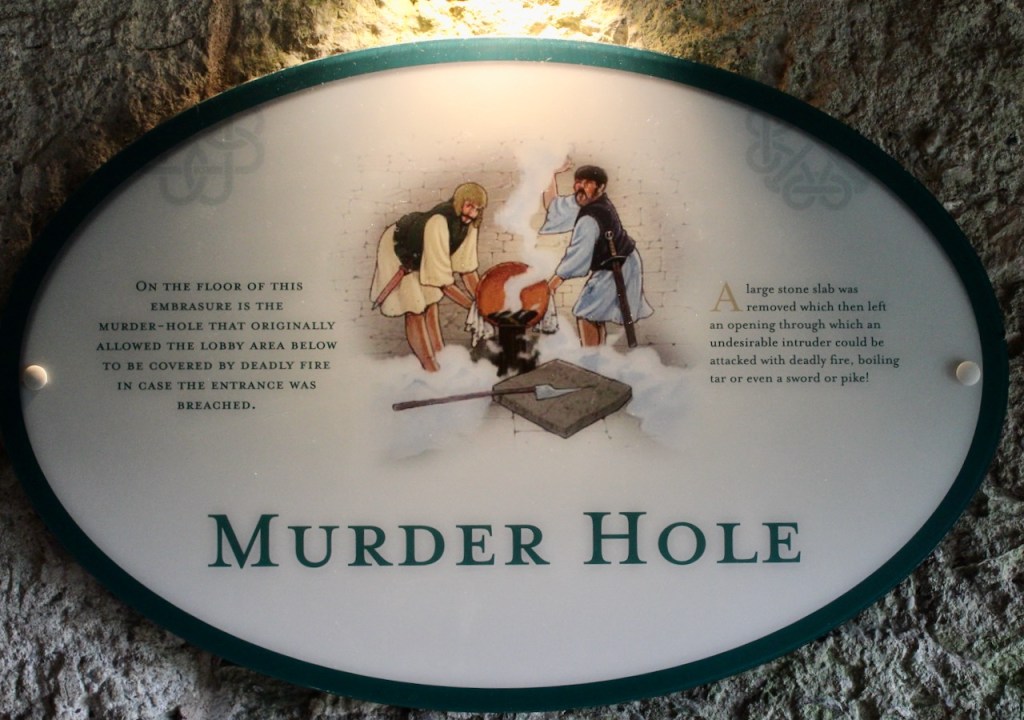

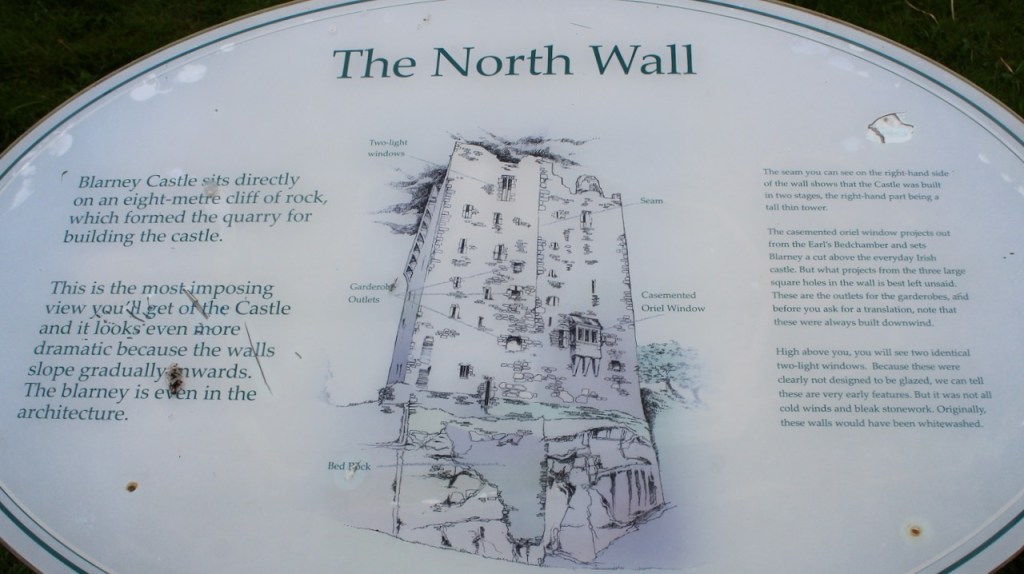

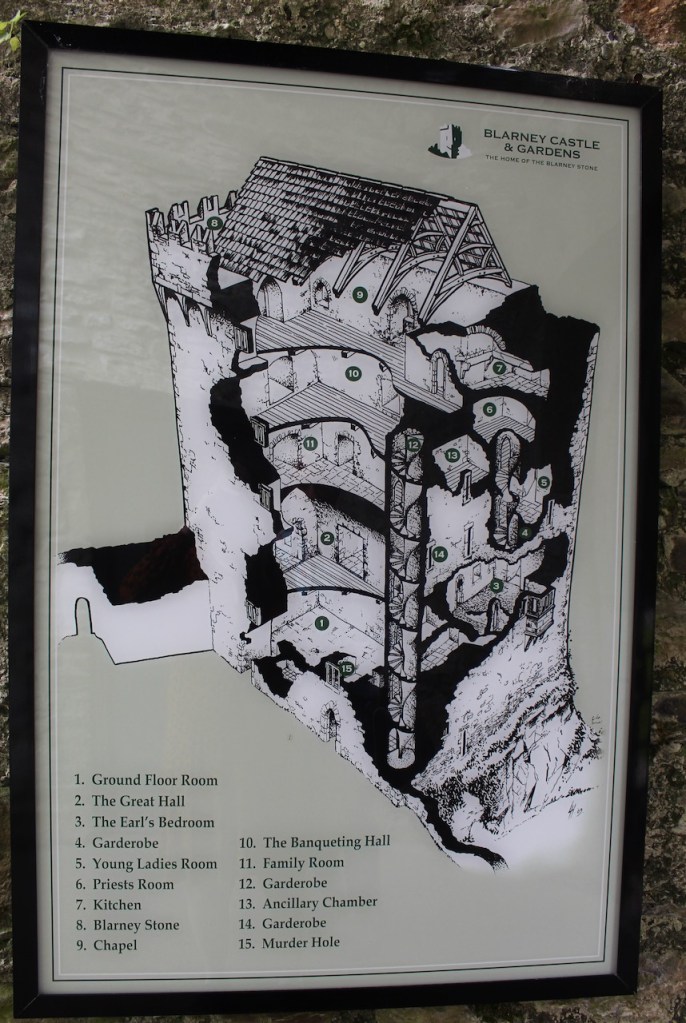

Once invaders get through the portcullis they are trapped in a small area, where defenders can fire arrows and stones at them. The walls of this area slope outwards towards the bottom, known as a base batter, so falling rocks bounce off them to hit the invaders.

The core of the castle is the keep.

Oliver Cromwell took the castle in 1650 and the occupants, under the 4th Baron Caher Piers Butler (d. 1676), surrendered peacefully.

The Butlers of Ormond also had to forfeit their land in the time of Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate. Both branches of the Butlers had their lands restored with the restoration of the monarchy with Charles II in 1662.

The Cahir website continues: “At the restoration of Charles II, in 1660, George Matthews, (as Warden of Cahir Castle and half-brother to the Duke of Ormond), retained the Cahir lands for the Lord Cahir, then a minor.” [4] George Matthew (or “Mathew,” 1645-1735) was married to Eleanor Butler, daughter of Edmond Butler, 3rd/13th Baron Dunboyne. She seems to have married twice: first to Edmond Butler son of 3rd Baron Cahir, then to to George Matthew. Her son was Piers Butler, 4th Baron Cahir, who was just seven when his father died.

Piers Butler 4th Baron Cahir (1641-1676) married George Mathew’s niece, Elizabeth Mathew (1647-1704). They had no male issue, but two daughters. His daughter Margaret married Theobald Butler, 5th Baron Cahir (d. 1700), great-grandson of the 1st Baron Cahir.

Margaret Butler daughter of the 4th Baron Cahir was the 5th Baron Cahir’s second wife. His first wife, Mary Everard, gave birth to his heir, Thomas (1680-1744), 6th Baron Cahir. Thomas had several sons, who became 7th (d. 1786) and 8th Barons Cahir (d. 1788), but they did not have children, so that title went to a cousin, James Butler (d. 1788), who became 9th Baron Cahir.

The Cahir website tells us: “Despite embracing the Jacobite Cause in the Williamite Wars, the Cahir estate remained relatively intact. However, the Butlers never again lived at Cahir Castle but rather at their country manor, Rehill House, where they lived in peace and seclusion from the mid-seventeenth century, when not living abroad in England and France.

“…By 1700 a sizeable town had grown around the Castle, although hardly any other buildings survive from this period. Agriculture, milling and a wide range of trades would have brought quite a bustle to the muddy precursors of our present streets. At this time, the Castle was quite dilapidated and was let to the Quaker William Fennell, who resided and kept a number of wool combers at work there.” [4]

The castle layout was changed considerably and enlarged during work to repair some of the damage caused by the battles, but was then left abandoned until 1840 when the partial rebuilding of the Great Hall took place. [4]

The Cahir website tells us: “On the completion of Cahir House [in the town, now Cahir House Hotel] in the later 1770’s, Fennell rented Rehill House from Lord Cahir and lived there over half a century. [The Barons moved to Cahir House.] A strong Roman Catholic middle class emerged. James [d. 1788], 9th Lord Cahir [d. 1788], practiced his religion openly. He maintained strong links with Jacobite France, and paid regular visits to England. While not a permanent resident, he kept his Cahir Estates in impeccable order and was largely responsible for the general layout of the Town of Cahir. Under his patronage, some of the more prominent buildings such as Cahir House, the Market House and the Inn were built during the late 1770s and early 1780s. In addition, the Quakers built the Manor Mills on the Bridge of Cahir, the Suir Mills (Cahir Bakery), and the Cahir Abbey Mills in the period 1775-90.” [4]

The son of the 9th Baron Cahir, Richard (1775-1819), became 10th Baron and 1st Earl of Glengall. It was he and his wife who had the Swiss Cottage built outside Cahir.

“… The young Lord Cahir married Miss Emily Jeffereys of Blarney Castle and together they led Cahir through the most colourful period of its development…Richard, Lord Cahir, sat in The House of Lords as one of the Irish Representative Peers, and in 1816 was created Earl of Glengall, a title he enjoyed for just 3 years. He died at Cahir House of typhus in January 1819, at the age of 43 years. Richard, Viscount Caher, (now 2nd Earl of Glengall), had already taken his place in political circles while his mother, Emily, ran the Estate with an iron fist.” [4]

“During the Great Famine (1846-51), Lord and Lady Glengall did much for the relief of the poor and the starving. Lord Glengall’s town improvement plan was shelved in 1847 due to a resulting lack of funds and his wife’s fortune being tied up in a Trust Fund. The Cahir Estates were sold in 1853, the largest portion being purchased by the Trustees of Lady Glengall. This sale came about due to Lord Glengall being declared bankrupt. The Grubbs had by now become the most important Quaker family in the district and bought parts of the Cahir Estate during the 1853 sale...

“In the interim, Lady Margaret Butler (elder daughter and heir of Lord Glengall) had married Lieut. Col. Hon. Richard Charteris, 2nd son of the 9th Earl of Wemyss & March. Using a combination of her mother’s Trust and Charteris funds, Cahir Town and Kilcommon Demesne were repurchased.

“Lady Margaret, although an absentee landlord, resident in London, kept a close watch on her Cahir Estates through two excellent managers, Major Hutchinson and his successor William Rochfort… Her son, Richard Butler Charteris took over her role in 1915 and remained resident in Cahir from 1916 until his death in 1961. In 1962, the House, and circa 750 acre estate core (within the walls of Cahir Park and Kilcommon Demesne) were auctioned…And so ended the direct line of Butler ownership in Cahir, almost 600 years.“ [4]

The castle became the property of the state after the death of Lord Cahir in 1961; it was classified as a national monument and taken into the care of the Office of Public Works. [6]

Our tour guide took us through the outside of the castle, showing us its defenses. Our tour ended inside the Great Hall, or dining hall.

The dining hall has a magnificent ceiling. The building would have originally been of two storeys, and taller. The appearance today owes much to restoratation work carried out by William Tinsley in 1840, when the building was converted into a private chapel for the Butler family. The hammer-beam roof and the south and east wall belong to this period. The external wall dates from the 13th century.

Next we explore the keep building.

[1] https://www.irelandscontentpool.com/en

[2] p. 58. Hayes, William and Art Kavanagh, The Tipperary Gentry volume 1 published by Irish Family Names, c/o Eneclann, Unit 1, The Trinity Enterprise Centre, Pearse Street, Dublin 2, 2003.

[3] http://www.thepeerage.com/index.htm and G.E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed., 13 volumes in 14 (1910-1959; reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000), volume IX, page 440.

[4] http://www.cahirhistoricalsociety.com/articles/cahirhistory.html

[5] https://repository.dri.ie/

[6] http://www.britainirelandcastles.com/Ireland/County-Tipperary/Cahir-Castle.html

Text © Jennifer Winder-Baggot, www.irishhistorichouses.com